Abstract

We reexamine the epidemiological paradox of lower overall infant mortality rates in the Mexican-origin population relative to US-born non-Hispanic whites using the 1995–2002 U.S. NCHS linked cohort birth-infant death files. A comparison of infant mortality rates among US-born non-Hispanic white and Mexican-origin mothers by maternal age reveals an infant survival advantage at younger maternal ages when compared to non-Hispanic whites, which is consistent with the Hispanic infant mortality paradox. However, this is accompanied by higher infant mortality at older ages for Mexican-origin women, which is consistent with the weathering framework. These patterns vary by nativity of the mother and do not change when rates are adjusted for risk factors. The relative infant survival disadvantage among Mexican-origin infants born to older mothers may be attributed to differences in the socioeconomic attributes of US-born non-Hispanic white and Mexican-origin women.

The epidemiological paradox of more favorable health and mortality outcomes for Hispanics relative to non-Hispanic whites in the United States is the subject of considerable research (Franzini et al. 2001; Guendelman 2000; Hummer et al. 2007; Landale et al. 2000; Markides and Coreil 1986; Markides and Eschbach 2005; Palloni and Morenoff 2001; Smith and Bradshaw 2006; Turra and Elo 2008). The paradox centers on the observation that, whereas the socioeconomic profile of some Hispanic groups with regard to educational attainment, income, and health insurance coverage, closely resembles that of non-Hispanic blacks, this group as a whole consistently experiences lower mortality rates by comparison. Perhaps the most puzzling patterns are found in the Mexican-origin population in the United States, whose mortality rates are similar to non-Hispanic whites—and much lower than those of non-Hispanic blacks—across most of the life course (Elo et al. 2004; Frisbie and Song 2003; Hummer et al. 2004; Liao et al. 1998; Rogers et al. 2000; Singh and Siahpush 2001, 2002).

Recent research traces some of the similarity in mortality rates between Mexican-origin and non-Hispanic white persons to the relatively lower mortality in the Mexican-origin immigrant population. The Mexican American population experiences moderately higher mortality rates than non-Hispanic whites, but they experience much lower mortality than non-Hispanic blacks. Considerable debate exists about the definition of the paradox and its underlying mechanisms. For the elderly Mexican-origin population, lower relative mortality could be a methodological artifact of outmigration, which implies that a portion of the at-risk population returns to Mexico to die and, as such, does not appear in the numerator of the relevant U.S. vital rates (Abraido-Lanza et al. 1999; Palloni and Arias 2004; Turra and Elo 2008). However, in the case of infant mortally, a detailed examination of age-specific mortality patterns by race, ethnicity, and nativity reveals lower infant mortality rates among foreign-born mothers when compared to US-born women and shows that implausible levels of outmigration at the earliest ages of death (i.e., within one week of birth) would be required to equalize Mexican-origin and non-Hispanic white infant mortality rates (Hummer et al. 2007).

Hummer at al. (2007) provide evidence that effectively closes the case on the paradox-as-data-artifact argument in the case of infant mortality in the neonatal period (i.e., within the first month of life). However, questions remain about the epidemiological paradox in infant mortality that cannot be answered by comparing overall rates or comparing age-specific mortality rates. For example, the U-shaped association of maternal age and infant heath is well-known (Geronimus 1986; Mathews and MacDorman 2008), and it is possible that the observed survival advantage of infants born to Mexican-origin mothers is mainly an artifact of that population’s relatively younger age structure and earlier average ages of family formation when compared to non-Hispanic whites (Poston and Dan 1996). If the distribution of births is skewed toward childbearing ages where maternal health endowments are most favorable, we would expect this to result in lower incidence of negative birth outcomes and lower overall infant mortality. In other words, the more favorable age structure of childbearing among Mexican-origin women relative to non-Hispanic whites may outweigh the negative effects of social disadvantage.

We argue that the maternal age distribution is important to consider when studying infant mortality differentials by race/ethnicity, and in particular, when comparing rates in the Mexican-origin and non-Hispanic white populations. Although it is commonplace to account for maternal age effects in multivariate models—and considerable past research points to its salience in helping to understand maternal health and infant mortality differentials—maternal age has thus far not assumed a central role in the investigation of the Hispanic infant mortality paradox. Specifically, in light of the age differences in childbearing across various populations, we may question whether the epidemiologic paradox is observed over the entire maternal age range.

This paper carries out a comparative analysis of infant mortality in the U.S. by race/ethnicity, nativity, and maternal age using the maternal age-specific rates obtained from several years of U.S. vital statistics data. We show that the Mexican-origin infant mortality paradox is evident and strong at younger maternal ages but disappears at older maternal ages, with patterns that differ by nativity. These patterns do not change significantly after adjusting for maternal risk and socioeconomic factors. We also show that the overall survival gap between non-Hispanic white and Mexican-origin infants is largely attributable to population differences in maternal-age specific infant mortality rates and not to population differences in the maternal age distributions. Finally, we show that differences in the population composition of older mothers on key socioeconomic attributes provides a partial explanation of the observed differences at older ages in terms of the selective survival advantage accruing to infants born to older non-Hispanic whites.

Background

Teller and Clybern (1974) presented perhaps the earliest evidence on the existence of an epidemiologic paradox for the U.S. Hispanic population when they showed that infant mortality rates in the Spanish surname population of Texas were somewhat lower than those of non-Hispanic whites during the 1960s. Markides and Coreil (1986) later reviewed evidence on numerous health indicators and concluded that for specific health outcomes (including infant mortality, life expectancy, cardiovascular disease mortality, mortality from major types of cancer, and measures of functional health), Hispanics exhibited rates that were much more similar to whites than to blacks even though the socioeconomic status of Hispanics is closer to that of blacks.

Explanations for the paradox include the positive health selectivity of immigrants, positive aspects of Hispanic culture, and data quality issues. The “healthy in-migrant” selectivity argument stresses the role of the process of immigration in selecting individuals who are positively selected on health, as well as on a number of observed and unobserved attributes (Elo, et al. 2011; Franzizi et al. 2001; Jasso et al. 2004; Markides and Eschbach 2005). Positive health selection is likely to be greatest at younger ages when the decision to migrate is based largely on economic reasons (Marmot et al. 1984; Palloni and Ewbank 2004). Thus, selectively healthy immigrant women of childbearing age would be expected to have healthier infants when compared to their non-selectively advantaged US-born counterparts (Hummer et al. 2007). This also suggests that the infant health advantages of Mexican immigrants will be most pronounced at earlier maternal ages.

Culture-based explanations tend to focus on characteristics that encourage healthy behaviors and the role of strong family ties in Hispanic immigrant communities in the U.S. (Cho et al. 2004; Franzizi et al. 2001; Scribner 1996). Immigrants in general, and recent immigrants in particular, differ from native born U.S. residents in terms of health-related behaviors, social support, and lifestyles, which operate as a “social-buffer” to ameliorate the effects of socioeconomic disadvantage and stress associated with the migration process (Jasso et. al. 2004). Therefore we would expect that immigrant mothers of modal childbearing ages—who face a higher probability of being recent arrivals—would have more favorable maternal health outcomes than Mexican Americans of the same age and of older Mexican immigrants and Mexican American mothers.

Recent demographic research on the data quality-based explanation focuses mainly on adult mortality. The core argument is that out-migration of Mexican-origin elders leads to loss to follow-up so that deaths occurring outside of the U.S. are not counted in the numerators of vital rates. This argument implies that the Mexican-origin mortality advantage is an artifact of return migration of less healthy immigrants, producing rates that are artificially low due to “salmon bias” (Abraido-Lanza et al. 1999; Palloni and Arias 2004). This hypothesis has recently been subjected to direct testing using Social Security Administration data on primary beneficiaries. Specifically, Turra and Elo (2008) find evidence of health-selective migration among Hispanics in terms of higher mortality among foreign-born Hispanics living abroad compared to their counterparts in the U.S. Although there is support for the salmon-bias hypothesis, its effect is too small to explain the lower mortality of Hispanics in the U.S.

In the case of infant mortality, the inability to link births in the U.S. to deaths that occur in Mexico has the potential to undermine the case for a paradox (Palloni and Morenoff 2001). There is undoubtedly some out-migration of Mexican-origin mothers and their infants out of the United States. However, the extent to which this is a plausible explanation of the paradox remains questionable. Hummer et al. (2007) present strong evidence against this explanation by noting that more than half of all infant mortality occurs within in the first week of life, and it is extremely unlikely that enough Mexican-origin mothers and infants would return to Mexico in sufficient numbers to impact U.S. vital rates. This research has effectively closed the case on the under-registration explanation of the Mexican-origin infant mortality epidemiologic paradox.

Although evidence suggests that the paradox is real, an analysis of overall race/ethnic mortality differentials, or differentials based on infant age at death, may mask important features of the dynamics of infant mortality when considered in combination with the maternal age structure of certain populations. In particular, there is a well-known curvilinear pattern of infant mortality by maternal age, with generally higher levels experienced by teenagers and older mothers (Freide, A., W. Baldwin, P. Rhodes, et al. 1987; Geronimus 1986; Mathews and MacDorman 2008). A great deal of research documents the interaction between age, race/ethnicity and the decline in reproductive health (Geronimus 1986; Geronimus 1992; Geronimus 1996). The “weathering hypothesis” delineated in this body of research suggests that individuals age at different rates as a consequence of differential levels of exposure to social disadvantage. This perspective is most often applied to non-Hispanic black/non-Hispanic white differences, yet the hypothesis likely pertains to adverse cumulative effects of stressors associated with long-term socioeconomic disadvantage and discrimination experienced by many minority groups.

Rates of deterioration in maternal health are associated with socioeconomic disadvantages at many levels. Minority populations are disproportionately concentrated in areas characterized by high levels of residential segregation and neighborhood disadvantage (Massey 2001; Rosenbaum and Friedman 2001). Mexican-origin populations experience higher levels of socioeconomic and neighborhood disadvantage relative to non-Hispanic whites (Saenz 1997; Markiedes and Coreil 1986; Albrecht et al. 1996), suggesting that Mexican-origin women would also be expected to experience weathering. Nativity has been shown to play a significant role in adverse pregnancy outcomes and infant mortality, with foreign-born populations generally experiencing more favorable outcomes than the native-born. Results from past research suggest a negative impact of “Americanization” on infant mortality (Hummer et al. 1999; Frisbie et al. 1998; Sing and Yu 1996), and low birth weight (Cobas et al. 1996; Scribner and Dwyer 1989). Therefore, we might expect to find increasing infant mortality gaps with maternal age within the Mexican origin population due to the more prolonged exposure of Mexican Americans to U.S. social conditions when compared to Mexican immigrants.

Previous studies find support for the weathering hypothesis when applied to the Mexican origin population. Wildsmith (2002) examined the age distribution of neonatal mortality within the Mexican-origin population and found that the optimal age at childbearing with regard to infant mortality occurs earlier among Mexican-American women than among Mexican immigrant women. Wildsmith’s finding of stronger weathering effects among Mexican Americans runs counter to assimilation theory (Gordon 1996), but is consistent with a segmented assimilation perspective that suggests increased divergence over time and across generations for Mexican Americans accompanied by increased disadvantage on multiple dimensions as a result of prolonged exposure to community-level socioeconomic disadvantage and race/ethnic discrimination (Portes 1995; Portes and Zhou 1993).

There is increasing evidence that a process of negative U.S. acculturation may work to erode the generally positive health and mortality outcomes among Hispanics over time and across generations (Ceballos and Palloni 2010; Cho et al. 2004; Jasso et al. 2004). A number of studies have attributed this “unhealthy assimilation” effect, or “acculturation paradox” to stress resulting from the process of acculturation and discrimination which can lead to behavioral and physiological changes that can increase the risk of illness (Finch et al. 2001; Finch and Vega 2003). Recent research has used clinical measurements associated with stress to examine weathering in the Mexican-origin population. Kaestner et al. (2009) quantify a number of biomeasures associated with cumulative exposure to chronic stressors into a composite measure of allostatic load, which is then dichotomized (high ≥ 3 or low < 3). These measures follow the conceptualization of McEwen and Seeman and colleagues (McEwen and Seeman 1999; Seemen et al. 1997). After controlling for a number of other risk factors, Kaestner et al. (2009) find that upon arrival to the U.S., older Mexican immigrants face lower odds of a high score when compared to U.S.-born reference groups. This advantage persists over time relative to non-Hispanic blacks, deteriorates relative to non-Hispanic whites, and tends to converge to the Mexican American odds. In the context of the present research, it is reasonable to consider maternal age as a proxy for length of time in the U.S. We can reasonably expect that maternal health advantages of Mexican immigrants may persist into later ages, but may converge to average levels faced by Mexican Americans.

Contribution of the Present Research

Given the race/ethnic and nativity variation in the maternal age profiles of childbearing, we question whether the Mexican-origin epidemiologic paradox is evident at all maternal ages or is characteristic of specific maternal age groups. A focus on maternal age casts the epidemiologic paradox within the conceptual framework of weathering, which argues that the cumulative impact of social inequality (i.e., repeated experience with social, economic, or political exclusion) is an important source of variability in health outcomes across populations in the United States. Although the most specific focus has been on African-American women, it seems likely that the conceptual framework of weathering applies equally to other socially-disadvantaged and marginalized populations—in particular to the Mexican American and Mexican immigrant populations.

Data and Methods

This analysis uses the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) linked birth and infant death cohort files for the years 1995–2002. These data include all infants born alive to US-born non-Hispanic white (NHW-US), US-born non-Hispanic black (NHB-US), and US-born and immigrant Mexican-origin women (MO-US, MO-FB) who were residents of the United States during those years (N = 26,578,118). As is customary in this literature, we use maternal identification reported on the birth certificate to ascertain the race and ethnicity of the infant; we exclude cases with missing identification information.

Results

Our central aim is to compare Mexican American and Mexican immigrant populations to US-born non-Hispanic whites. We begin by examining the maternal age-distribution for all births and first births.

Maternal Age Distribution

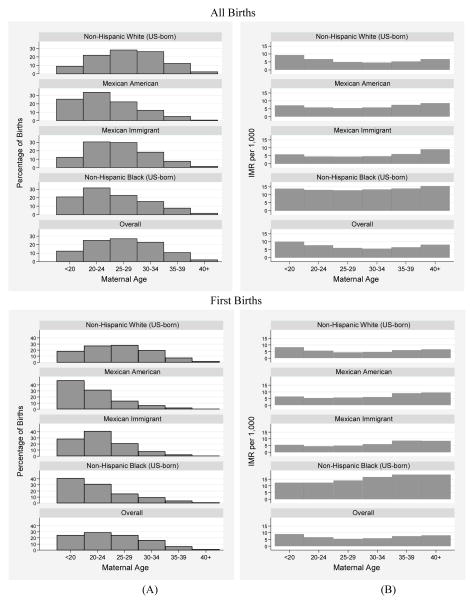

The maternal age distribution differs across populations due to different population age structures and other factors. This difference could mask important maternal age-specific infant mortality patterns. Panel A of Table 1 and Panel A of Figure 1 show the age distribution of mothers from the 1995–2002 NCHS data. We see that non-Hispanic whites have a more protracted childbearing experience when compared to Mexican-origin populations and to non-Hispanic blacks. The maternal age dynamics are such that 59% of the births to US-born Mexican-origin (i.e., Mexican American) and 43% of foreign-born Mexican-origin (i.e., Mexican immigrant) women occur under the age of 25, compared to 31% of the births to non-Hispanic whites. Panel B of Table 1 and the lower Panel A of Figure 1 show the age distribution of primiparous women. Whereas 45% of first births occur before age 25 to non-Hispanic whites, between 60% and 78% of first births occur to Mexican-origin women at these ages. The age profile of first births among Mexican-origin women is similar to that of non-Hispanic blacks, where 75% of first births occur before age 25.

Table 1.

Infant Mortality Rates by Maternal Age and Nativity for Non-Hispanic White, Mexican-Origin, and Non-Hispanic Black Women: 1995–2002 Linked Files

| A | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Births | Maternal Age | NHW US | MO US | MO FB | NHB US | OVERALL | |||||

| % | IMR | % | IMR | % | IMR | % | IMR | % | IMR | ||

| < 20 | 9.3 | 9.3 | 25.5 | 7.2 | 12.3 | 5.9 | 22.6 | 14.0 | 12.7 | 10.1 | |

| 20–24 | 22.3 | 6.8 | 33.8 | 5.8 | 30.4 | 4.6 | 33.0 | 13.4 | 25.5 | 7.8 | |

| 25–29 | 28.0 | 5.0 | 22.2 | 5.5 | 29.7 | 4.4 | 22.1 | 13.4 | 26.9 | 6.1 | |

| 30–34 | 25.9 | 4.6 | 12.5 | 5.8 | 18.3 | 4.8 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 22.5 | 5.6 | |

| 35–39 | 12.1 | 5.3 | 5.1 | 7.5 | 7.6 | 6.1 | 6.7 | 14.7 | 10.3 | 6.4 | |

| 40+ | 2.3 | 6.7 | 0.9 | 8.6 | 1.7 | 9.1 | 1.4 | 15.8 | 2.0 | 7.9 | |

| Total | 100 | 5.8 | 100 | 6.2 | 100 | 4.9 | 100 | 13.7 | 100 | 7.0 | |

| Deaths | 104,200 | 10,192 | 13,229 | 58,039 | 185,660 | ||||||

| Births | 18,021,839 | 1,638,104 | 2,689,077 | 4,229,098 | 26,578,118 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| B | |||||||||||

| First Births | Maternal Age | NHW US | MO US | MO FB | NHB US | OVERALL | |||||

| % | IMR | % | IMR | % | IMR | % | IMR | % | IMR | ||

| <20 | 18.6 | 8.4 | 47.0 | 6.6 | 28.1 | 5.5 | 43.8 | 12.3 | 25.0 | 8.9 | |

| 20–24 | 26.9 | 5.7 | 31.4 | 5.5 | 40.8 | 4.5 | 31.4 | 12.8 | 29.0 | 6.7 | |

| 25–29 | 27.4 | 4.5 | 13.3 | 5.8 | 20.9 | 5.0 | 13.5 | 15.2 | 23.9 | 5.5 | |

| 30–34 | 18.9 | 4.7 | 6.0 | 6.1 | 7.5 | 5.9 | 7.6 | 17.7 | 15.4 | 5.8 | |

| 35–39 | 6.9 | 6.1 | 2.0 | 9.0 | 2.2 | 8.6 | 3.1 | 18.9 | 5.6 | 7.3 | |

| 40+ | 1.3 | 6.7 | 0.3 | 9.5 | 0.4 | 8.4 | 0.6 | 17.2 | 1.1 | 7.7 | |

| Total | 100 | 5.7 | 100 | 6.2 | 100 | 5.1 | 100 | 13.5 | 100 | 6.9 | |

| Deaths | 42,770 | 4,076 | 4,617 | 21,650 | 73,113 | ||||||

| Births | 7,462,601 | 661,038 | 904,990 | 1,604,902 | 10,633,531 | ||||||

Figure 1.

(A) Percentage of births occurring in specific maternal age ranges by race/ethnicity. (B) IMR per 1,000 in specific maternal age ranges by race/ethnicity.

Maternal Age-Specific IMRs

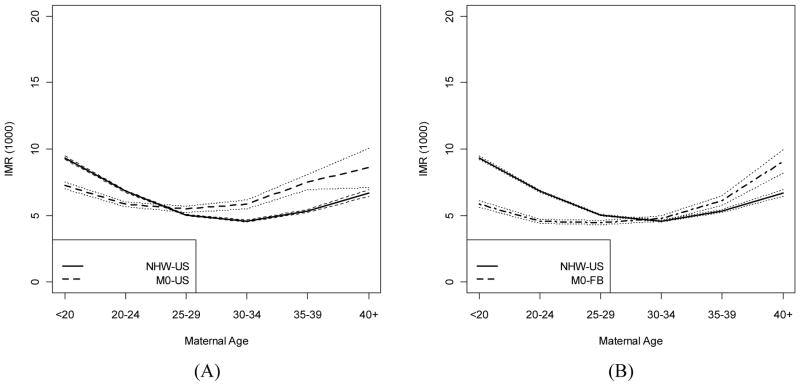

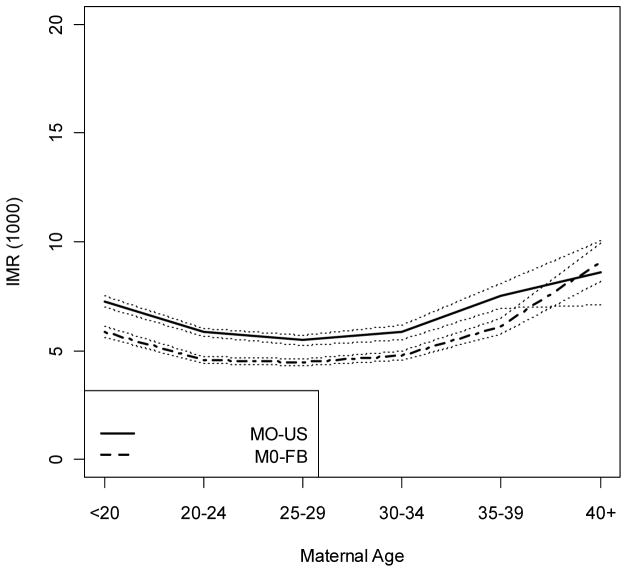

The maternal age specific IMRs (per 1,000 live births) in Panel A of Table 1 and Panel B of Figure 1 show the typical U-shaped pattern for all populations (i.e., initially high rates that decrease through prime childbearing years and increase at older ages). It is useful to compare the maternal age-specific patterns to the overall rates. We see that Mexican Americans have higher overall rates and Mexican immigrants have lower overall rates than non-Hispanic whites. These patterns are very similar for primiparous women. However, the maternal age-specific patterns in Table 1 and Panel B of Figure 1 tell a different story. For the Mexican-origin population, there is a clear crossover from an infant survival advantage at ages younger than 30 to an increasing survival disadvantage at later ages relative to non-Hispanic whites. For Mexican Americans, this crossover occurs after age 24, while for Mexican immigrants the crossover occurs after age 29, as shown in Panels A and B of Figure 2. Therefore, the relatively smaller number of Mexican-origin mothers age 30 or older comprise a higher risk group relative to non-Hispanic whites at those ages, while young Mexican-origin women are a much lower risk group when compared to younger non-Hispanic whites.

Figure 2.

IMR (per 1,000): (A) Mexican American maternal age-specific IMR (dashed lines) compared to US-born non-Hispanic whites (solid lines) with 95% point-wise confidence intervals (dotted lines). (B) Mexican immigrant maternal age-specific IMR (dashed lines) compared to US-born non-Hispanic whites (solid lines) with 95% point-wise confidence intervals (dotted lines).

Table 2 shows the maternal age-specific IMR ratios (rate ratios) for each group relative to non-Hispanic whites. We see that the rate ratios for non-Hispanic blacks are uniformly higher at all maternal ages. The rate ratios in Table 2 quantify the excess mortality risk for Mexican-origin infants born to older mothers. Specifically, infants born to Mexican American women 25 and older face a 9 to 41 percent higher risk of dying when compared to their non-Hispanic white counterparts, while infants born to Mexican immigrants age 30 or older have risks that are 4 to 36 percent higher. [Table 2 about here]

Table 2.

Rate Ratios Relative to US Born Non-Hispanic Whites by Maternal Age and Nativity: All Births and First Births, 1995–2002 Linked Files

| All Births | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Age | MO US | MO FB | NHB US |

| <20 | 0.77* | 0.63* | 1.50* |

| 20–24 | 0.86* | 0.67* | 1.96* |

| 25–29 | 1.09* | 0.89* | 2.67* |

| 30–34 | 1.28* | 1.04* | 3.07* |

| 35–39 | 1.41* | 1.15* | 2.75* |

| 40+ | 1.29* | 1.36* | 2.37* |

| Overall | 1.08* | 0.85* | 2.37* |

| First Births | |||

| Maternal Age | MO US | MO FB | NHB US |

| <20 | 0.79* | 0.66* | 1.46 |

| 20–24 | 0.95* | 0.78* | 2.24* |

| 25–29 | 1.30* | 1.11* | 3.40* |

| 30–34 | 1.29* | 1.26* | 3.74* |

| 35–39 | 1.47* | 1.40* | 3.09* |

| 40+ | 1.41 | 1.25 | 2.55* |

| Overall | 1.08* | 0.89* | 2.35* |

Significantly different from 1.0 (p < 0.05 two tailed test)

Standardization Analysis

The sensitivity of these findings can be gauged by fitting multivariate models that adjust for risk factors. Before conducting such an analysis, we carry out a standardization that considers the maternal age distribution of births and the maternal age-specific infant mortality rates as the sole sources of the difference in crude IMRs between the Mexican-origin and non-Hispanic white populations. Of central interest is the question: What would be the overall IMR in the Mexican-origin population if they were characterized by the maternal age structure of non-Hispanic whites? We consider a hypothetical scenario based on the maternal age-specific rates and the maternal age distribution of births given in Table 1 and apply direct standardization to evaluate the overall infant mortality rates in selected populations under alternative maternal age distributions.

Demographic standardization and decomposition techniques—generally referred to as component analysis—were formally developed by Kitagawa (1955) and generalized by Das Gupta (1993). The standardization approach substitutes the maternal age distribution or the maternal age specific infant mortality rates of a reference population (i.e., non-Hispanic whites) with those of the comparison population (i.e., Mexican Americans or Mexican immigrants), while holding one or the other of these components constant for the comparison group. More formally, this approach defines rjk to be the IMR in population j and maternal age category k, or the maternal age specific IMR. The overall IMR in population j under the maternal age distribution of population j′ can be expressed as pjj′ = Σk rjk aj′k, where aj′k denotes the proportion of births in maternal age category k in population j′. For any two populations, this procedure yields the overall IMR in population 1 (p11), the overall IMR in population 2 (p12), the expected IMR in population 1 under the maternal age specific infant mortality rates of population 2 (p12), as well as the expected IMR in population 1 under the maternal age structure of population 2 (p21). The standardization is most effectively carried out using matrix operations, where R denotes a 2×6 matrix of maternal age-specific infant mortality rates for two populations and A denotes a 6×2 matrix of the respective maternal age distributions obtained from Panel A of Table 1. Following the approach of Althauser and Wigler (1972), we carry out a direct standardization in which the overall standardized and unstandardized rates are the elements of the matrix P = RA.

A standardization based on the Mexican American and non-Hispanic white populations gives:

The diagonal entries are the overall IMRs for non-Hispanic whites (p11) and Mexican-Americans (p22) shown in Table 1 (Panel A). We consider the elements of P to be point estimates subject to sampling variability (see, e.g., Brillinger 1986) and construct interval estimates of the IMRs according to the methods described in Mathews and MacDorman (2008).2 The first off-diagonal entry p12 = 6.74 (95% CI = 6.63, 6.84) is interpreted as the Mexican-American IMR subject to the non-Hispanic white maternal age-specific mortality rates.3 The interval estimates fall outside those for Mexican American infants ( p22 = 6.22, 95% CI = 5.93, 6.51). Mexican American infants would therefore be expected to face a survival disadvantage if characterized by the non-Hispanic white maternal age-specific mortality rates.

The 2nd off-diagonal entry p21 = 6.12 (95% CI = 5.79, 6.45) is the expected Mexican-American IMR under the non-Hispanic white maternal age distribution.4 The interval estimates are within the bounds of the IMR for Mexican American infants, implying that Mexican American infants would face neither a survival advantage nor a disadvantage under the non-Hispanic white maternal age distribution.5 Further analysis of these components reveals that 77% of the Mexican-American-non-Hispanic white differential in crude IMR can be attributed to differences in maternal age-specific mortality rates, with the remainder owing to population differences in the maternal age distribution.6

A standardization based on the Mexican immigrant and non-Hispanic white populations gives:

where the elements of P are interpreted as before. Here we would expect to find a much higher overall IMR (6.07 vs. 4.92) among Mexican immigrant infants if their maternal age-specific mortality equaled that of non-Hispanic whites (p12 = 6.07, 95% CI = 5.98, 6.16). We would also expect to find a somewhat higher IMR in the Mexican immigrant population when characterized by the maternal age distribution of non-Hispanic whites (p21 = 4.99, 95% CI = 4.78, 5.21). However, interval estimates of the standardized rates lie within the unstandardized Mexican immigrant interval estimates (p22 = 4.92, 95% CI = 4.72, 5.12). A component analysis reveals that about 92% of the Mexican-immigrant-non-Hispanic white IMR differential can be attributed to differences in maternal age-specific mortality rates, with the remainder due to differences in the maternal age distributions.

Although it seems plausible to attribute the relatively lower IMR in the Mexican-origin population as a whole to the younger age composition of their births, the overwhelming contribution to the IMR differential between non-Hispanic whites and the Mexican-origin groups is attributable to differences in the maternal age-specific rates, with only a small contribution owing to population differences in maternal age distributions. Evidence thus far suggests that differences in maternal age-specific mortality account for the difference in overall infant mortality between Mexican-origin and non-Hispanic whites and that overall IMR differences are not simply artifacts of differences in maternal age distributions.

Multivariate Models: Risk Factors and Model Specification Risk Factors

It remains to be seen if the observed patterns in maternal age-specific IMRs persist after adjustment for maternal health risk factors and sociodemographic characteristics. In particular, are the observed maternal age crossovers adjusted away if we account for risk factors whose impacts differ by age? Here we investigate how age-specific infant mortality patterns respond to adjustments for risk factors using a multivariate analysis. We consider sociodemographic risk factors as analytically distinct from, but not necessarily independent of maternal/biological risk factors. This perspective is consistent with the social-conditions of health conceptual framework outlined by Link and Phelan (1995). The NCHS data lack the biomarkers that have been traditionally used to measure stress according to the conceptualization of McEwen and Seeman and colleagues (McEwen and Seeman 1999; Seeman et al. 1997). However, one maternal/biological risk factor included in our multivariate model (maternal morbidity) shows a steeper rate of change with age in all three minority populations.

When building the analytic model we consider an array of risk factors including clinically recognized maternal health and biological factors that are viewed as proximate determinants of birth outcomes and infant mortality, in addition to sociodemographic risk factors. The goal is to examine adjusted maternal age specific rates and rate ratios after controlling for risk factors. We present results for non-Hispanic whites, Mexican Americans, Mexican immigrants, and non-Hispanic blacks, but focus mainly on comparisons between Mexican-origin and non-Hispanic white infants. The analytic model includes a binary variable maternal morbidity, coded 1 (0 otherwise) for a positive response to the presence of any of the following: anemia, cardiac disease, acute or chronic lung disease, diabetes, genital herpes, hydramnios/oligohydramnios, hemoglobinopathy, chronic hypertension, hypertension (pregnancy-associated), eclampsia, incompetent cervix, previous infant weighing 4,000 grams or more, birth to a previous preterm or small-for-gestational-age infant, renal disease, Rh sensitization, uterine bleeding, and other medical risk factors. A binary variable labor complications is constructed in a similar manner, and coded 1 (0 otherwise) for a positive response to any of the following: febrile (>100 degrees F or 38 degrees C), meconium (moderate/heavy), premature rupture of membrane (>12 hours), abruptio placenta, placenta previa, other excessive bleeding, seizures during labor, precipitous labor (<3 hours), prolonged labor (>20 hours), dysfunctional labor, breech/malpresentation, cephalopelvic disproportion, cord prolapsed, anesthetic complications, fetal distress, and other complications of labor and/or delivery.

The full model includes two measures derived from the Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization (APNCU) Index (Kotelchuck 1994). To classify adequacy of received services, the number of prenatal visits is compared to the expected number of visits for the period between when care began and delivery date. The expected number of visits is based on the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists prenatal care standards for uncomplicated pregnancies and is adjusted for gestational age when care began and for gestational age at delivery. A ratio of observed to expected visits is calculated and grouped into 4 categories. The 1st category (adequate-plus prenatal care) is considered an indicator of a problem pregnancy, whereas the 4th category represents inadequate prenatal care. Our multivariate model includes adequate-plus prenatal care (i.e., possibly indicating maternal health problems during pregnancy) and inadequate prenatal care (i.e., indicating fewer than expected number of prenatal care visits). Additional risk factors include pregnancy loss (i.e., coded 1 if the total number of births is greater than the total number of live births and 0 if they are equal), plural birth (i.e., non-singleton), maternal smoking (i.e., tobacco use during pregnancy and in the 3 months prior to pregnancy), being unmarried, low maternal education (i.e., having less than a high school education), first birth, and high parity (i.e., 4 or more previous births). 7

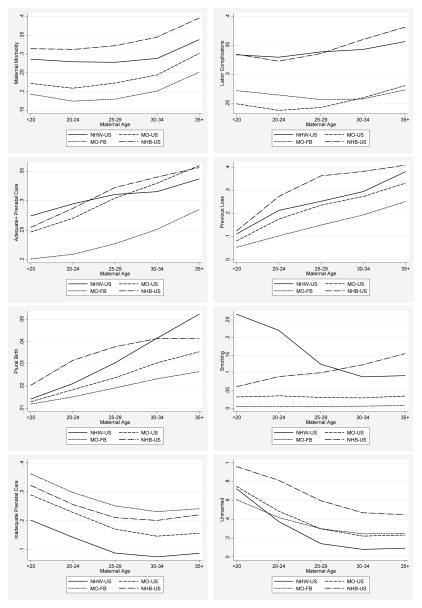

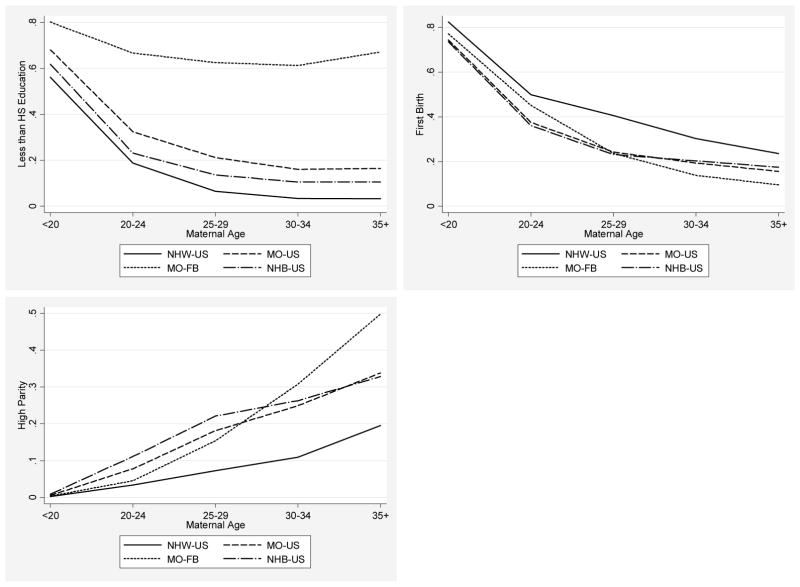

Table 3 and Figure 3 show the distribution of risk factors as they vary by maternal age across populations. The distribution of these factors varies by age in a predictable way. Non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks exhibit the highest prevalence of maternal health problems at any age. Although there is a tendency for the percentage of women with risk factors associated with maternal morbidity to increase with age, we find a narrowing gap between non-Hispanic white and Mexican-American women after age 25, which is due to the relatively steeper rates of change in these conditions among Mexican-origin women. In contrast, the percentage of women with adequate-plus prenatal care is higher for Mexican Americans compared to non-Hispanic whites over age 30, and the proportion receiving inadequate prenatal care is higher at all ages. Mexican immigrant women are more highly represented among the proportion receiving inadequate prenatal care. This has possible data quality implications. For example, less prevalence of prenatal care among Mexican immigrants may result in incomplete reporting of the conditions on the birth certificate related to maternal morbidity. We also find a higher representation of Mexican immigrant and non-Hispanic black women among the low-educated and in the high-parity group. Mexican-origin and non-Hispanic black women are also less likely to be married at the time of the birth compared to other groups.

Table 3.

Distribution of Risk Factors by Maternal Age, Race/Ethnicity, and Nativity†

| Maternal Age | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Factors | <20 | 20–24 | 25–29 | 30–34 | 35+ | Total |

| maternal morbidity | ||||||

| NHW | 28.6% | 27.9% | 27.8% | 28.8% | 33.8% | 29.0% |

| NHB | 31.4% | 31.2% | 32.2% | 34.5% | 39.6% | 32.6% |

| MO-US | 22.2% | 20.9% | 22.3% | 24.4% | 30.1% | 22.5% |

| MO-FB | 19.3% | 17.4% | 18.0% | 20.1% | 25.1% | 19.0% |

| Total | 27.7% | 26.8% | 27.0% | 28.5% | 33.6% | 28.2% |

| labor complications | ||||||

| NHW | 33.4% | 33.0% | 33.9% | 34.3% | 35.7% | 34.0% |

| NHB | 33.5% | 32.3% | 33.6% | 36.0% | 38.1% | 33.8% |

| MO-US | 24.9% | 23.8% | 24.3% | 26.0% | 28.1% | 24.7% |

| MO-FB | 27.2% | 26.5% | 25.7% | 25.8% | 27.3% | 26.3% |

| Total | 31.7% | 31.3% | 32.4% | 33.5% | 35.0% | 32.6% |

| adequate-plus prenatal care | ||||||

| NHW | 27.4% | 29.5% | 31.1% | 31.6% | 33.7% | 30.9% |

| NHB | 25.5% | 28.7% | 32.3% | 34.0% | 35.7% | 30.1% |

| MO-US | 24.7% | 27.0% | 30.5% | 33.0% | 36.0% | 28.5% |

| MO-FB | 20.1% | 20.9% | 22.7% | 25.1% | 28.5% | 22.8% |

| Total | 25.8% | 28.1% | 30.3% | 31.3% | 33.6% | 29.8% |

| previous loss | ||||||

| NHW | 11.1% | 21.3% | 25.3% | 29.5% | 38.2% | 26.0% |

| NHB | 12.5% | 27.4% | 36.4% | 38.3% | 41.0% | 28.6% |

| MO-US | 8.1% | 17.5% | 23.6% | 27.4% | 33.2% | 18.7% |

| MO-FB | 5.3% | 10.2% | 14.9% | 19.4% | 25.1% | 14.1% |

| Total | 10.5% | 20.9% | 25.5% | 29.4% | 37.3% | 24.8% |

| plural birth | ||||||

| NHW | 1.4% | 2.1% | 3.0% | 4.2% | 5.2% | 3.3% |

| NHB | 2.0% | 3.2% | 3.8% | 4.1% | 4.1% | 3.3% |

| MO-US | 1.3% | 1.8% | 2.4% | 3.0% | 3.5% | 2.1% |

| MO-FB | 1.2% | 1.5% | 1.9% | 2.3% | 2.6% | 1.8% |

| Total | 1.6% | 2.2% | 3.0% | 4.0% | 4.9% | 3.1% |

| smoking | ||||||

| NHW | 26.6% | 22.1% | 12.5% | 8.9% | 9.2% | 14.5% |

| NHB | 6.1% | 8.9% | 10.1% | 12.3% | 15.5% | 9.6% |

| MO-US | 3.2% | 3.5% | 3.0% | 2.9% | 3.4% | 3.2% |

| MO-FB | 1.2% | 1.5% | 1.9% | 2.3% | 2.6% | 1.8% |

| Total | 15.4% | 15.2% | 10.3% | 8.3% | 9.1% | 11.6% |

| inadequate prenatal care | ||||||

| NHW | 20.3% | 14.4% | 8.9% | 7.6% | 8.9% | 10.8% |

| NHB | 32.2% | 25.7% | 21.1% | 20.2% | 22.1% | 25.1% |

| MO-US | 29.0% | 22.9% | 17.1% | 14.7% | 15.7% | 21.7% |

| MO-FB | 36.2% | 29.8% | 25.2% | 23.2% | 24.2% | 27.5% |

| Total | 26.3% | 19.2% | 12.7% | 10.4% | 11.6% | 15.4% |

| unmarried | ||||||

| NHW | 72.5% | 37.7% | 14.1% | 8.1% | 9.3% | 22.6% |

| NHB | 96.0% | 81.6% | 59.8% | 47.0% | 44.9% | 72.2% |

| MO-US | 74.9% | 48.6% | 29.9% | 22.2% | 23.2% | 46.3% |

| MO-FB | 60.8% | 41.9% | 30.1% | 24.5% | 24.7% | 35.9% |

| Total | 78.3% | 48.1% | 22.7% | 13.8% | 14.6% | 33.3% |

| less than HS education | ||||||

| NHW | 56.2% | 18.8% | 6.5% | 3.4% | 3.2% | 12.6% |

| NHB | 61.9% | 23.1% | 13.6% | 10.5% | 10.5% | 27.0% |

| MO-US | 68.1% | 32.5% | 21.2% | 16.0% | 16.5% | 36.0% |

| MO-FB | 80.2% | 66.7% | 62.6% | 61.3% | 67.1% | 66.2% |

| Total | 61.6% | 26.6% | 14.5% | 9.3% | 9.2% | 21.8% |

| first birth | ||||||

| NHW | 82.4% | 49.9% | 40.5% | 30.2% | 23.6% | 41.4% |

| NHB | 73.6% | 36.1% | 23.1% | 20.3% | 17.5% | 37.9% |

| MO-US | 74.4% | 37.5% | 24.2% | 19.3% | 15.6% | 40.4% |

| MO-FB | 77.1% | 45.2% | 23.7% | 13.8% | 9.6% | 33.7% |

| Total | 78.4% | 45.5% | 35.5% | 27.5% | 21.7% | 40.0% |

| high parity | ||||||

| NHW | 0.2% | 3.4% | 7.2% | 10.9% | 19.5% | 8.4% |

| NHB | 0.9% | 11.1% | 22.1% | 26.3% | 32.8% | 15.1% |

| MO-US | 0.5% | 7.8% | 18.1% | 24.9% | 33.8% | 11.9% |

| MO-FB | 0.4% | 4.5% | 15.4% | 30.7% | 49.8% | 16.2% |

| Total | 0.4% | 5.5% | 10.6% | 14.6% | 23.6% | 10.5% |

| N | 3,384,638 | 6,784,716 | 7,150,148 | 5,970,410 | 3,288,206 | 26,578,118 |

Summary measures are calculated using non-missing data. N’s include all observations.

Figure 3.

Proportion of mothers with a given risk factor by maternal age, race/ethnicity/nativity.

Proportion of mothers with a given risk factor by maternal age, race/ethnicity/nativity.

Multivariate Adjustment

We fit a multivariate model that permits the effects of risk factors to vary across subpopulations by maternal age. This allows prediction of maternal age-specific infant mortality rates that would prevail in each subpopulation if risk factors were eliminated. The purpose of the model is to adjust for, rather than to interpret, effects of risk factors, all of which are expected to operate in predictable ways. We specify separate models for each subpopulation in reference to non-Hispanic whites. The resulting log rate ratios and their standard errors are used for significance testing using a general specification for the log probability of mortality for the ith infant in each of 5 maternal age categories: <20, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, and >34. We use a somewhat coarser age classification than was used with the descriptive statistics in order to maximize statistical precision of the maternal age effects in the multivariate models. The model is specified as a generalized linear (loglinear rate or log probability) model in log pi, where pi = Pr(di = 1), and di = 1 denotes infant death and di = 0 denotes survival.8 Specifically,

| (1) |

where Rj is a factor denoting a specific maternal race/ethnicity/nativity category j ∈ {non-Hispanic white, other}, and where “other” denotes one of the 3 other race/ethnic/nativity comparison groups. Xk denotes the kth risk factor and M1–M5 denote the 5 maternal age categories. This model is estimated by evaluating two populations at a time in which each “other” group is contrasted with non-Hispanic whites, yielding 3 separate models. The model does not impose proportionality constraints on effects, thus allowing for maximum variation in the effects of risk factors by race/ethnicity, nativity, and maternal age. As a consequence of this specification, the number of parameters (i.e., the total number of a’s and b’s in Eq. (1) ) is 10 and 125 in Model 1 (the baseline model) and Model 2 (the full model), respectively. To maintain identical samples across models and to maximize the amount of data used, we include dummy variables for missing information on maternal education (pct. missing =1.29%), maternal morbidity (pct. missing=1.19%), and smoking (pct. missing = 16.3%).9 All other maternal risk and sociodemographic factors consisted of less than 1% missing data. In addition to including the missing indicators, we recoded risk factors to 0 (the reference category) in the case missing data. Given a data set of over 26 million births and over 185 thousand infant deaths, the statistical precision of all estimates is very high. This model provides a flexible specification yielding risk-adjusted maternal age-specific IMRs and rate ratios for each group relative to non-Hispanic whites, which are reported in Table 4.

Table 4.

Multivariate Models: Predicted IMR per 1000, Rate Ratios, and Percent Reduction in Predicted IMR from Observed IMR

| Model 1a | NHW US | MO US | MO FB | NHB US | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Age | IMR | % | RR | IMR | % | RR | IMR | % | RR | IMR | % | RR |

| < 20 | 9.3 | NA | 1* | 7.2 | NA | 0.77* | 5.9 | NA | 0.63* | 14.0 | NA | 1.50* |

| 20–24 | 6.8 | NA | 1* | 5.8 | NA | 0.86* | 4.6 | NA | 0.67* | 13.4 | NA | 1.96* |

| 25–29 | 5.0 | NA | 1* | 5.5 | NA | 1.09* | 4.4 | NA | 0.89* | 13.4 | NA | 2.67* |

| 30–34 | 4.6 | NA | 1* | 5.8 | NA | 1.28* | 4.8 | NA | 1.04* | 14.1 | NA | 3.07* |

| >34 | 5.5 | NA | 1 | 7.7 | NA | 1.38* | 6.7 | NA | 1.20† | 14.9 | NA | 2.68* |

| Model 2b | NHW US | MO US | MO FB | NHB US | ||||||||

| Maternal Age | IMR | % | RR | IMR | % | RR | IMR | % | RR | IMR | % | RR |

| < 20 | 3.7 | 60.3% | 1 | 2.7 | 62.1% | 0.74* | 2.1 | 64.5% | 0.56* | 6.0 | 57.4% | 1.60* |

| 20–24 | 2.2 | 67.0% | 1* | 1.9 | 67.5% | 0.84* | 1.5 | 67.0% | 0.67* | 4.0 | 70.2% | 1.76* |

| 25–29 | 1.4 | 72.9% | 1 | 1.5 | 71.8% | 1.14* | 1.3 | 70.8% | 0.96 | 3.1 | 76.5% | 2.30* |

| 30–34 | 1.2 | 74.9% | 1 | 1.4 | 76.2% | 1.21* | 1.3 | 73.6% | 1.09* | 2.9 | 79.3% | 2.52* |

| >34 | 1.4 | 75.4% | 1* | 2.2 | 70.7% | 1.65* | 1.9 | 71.7% | 1.38* | 3.6 | 75.7% | 2.63* |

Maternal age only

Maternal age and maternal risk factors: maternal morbidity, labor complications, adequate-plus prenatal care, previous loss, plural birth, smoking, first birth, high parity, inadequate prenatal care, unmarried, and less than 12 years of education. All risk factors are interacted with the dummy variables corresponding to maternal age categories with interactions varying by race/ethnicity and nativity. Models include indicator variables for missing data.

Statistically different from 1.0 p < 0.05

Statistically different from 1.0 p < 0.10

Model 1 (the baseline model) in Table 4 includes only maternal age and therefore reproduces the observed maternal age-specific IMRs and rate ratios. Model 2 (the full model) includes all the aforementioned maternal health and sociodemographic risk factors, each of which is interacted with race/ethnicity/nativity and maternal age. Focusing on the Mexican-origin/non-Hispanic white comparisons, we find that the crossover from a survival advantage for Mexican-origin infants of younger mothers to a survival disadvantage for infants of older mothers persists after adjusting for risk factors. For Mexican Americans, the rate ratios (RR) relative to US born whites remain similar. The predicted maternal age specific rates (i.e., conditional on risk factors) are adjusted downward, with the extent of downward adjustment given by the percent reduction column labeled %Δ in Table 4. We find that the predicted, or risk-adjusted, rates for non-Hispanic whites are 60.3% to 75.4% lower after adjustment for risk factors, while the adjusted rates for Mexican Americans are 62.1% to 76.2% lower than the observed rates. For both Mexican Americans and Mexican immigrants the predicted IMRs for the youngest maternal age interval reflect a larger mortality decline when compared to non-Hispanic whites. In this case, eliminating risk factors would be expected to result in a moderately improved survival advantage for Mexican origin infants relative to non-Hispanic whites at those ages. The predicted IMRs for other maternal age intervals are not adjusted downward to a similar extent, with the exception of the predicted IMR for Mexican American infants born to 30–34 year old mothers. Thus, adjusting for risk factors has somewhat less impact on the mortality of infants born to older Mexican-origin women when compared to their younger counterparts and when compared to non-Hispanic whites.

Adjusting for risk factors has less impact on the reduction in mortality of non-Hispanic black infants born to teen mothers. However, rates are adjusted downward by 70.2 to 79.3 percent for infants born to older women, which lead to modest reductions in IMR ratios relative to non-Hispanic whites when compared to the empirical maternal age-specific IMRs.

Differences within the Mexican Origin Population

A further comparison of Mexican American and Mexican immigrant rates is relevant in light of the weathering hypothesis. If weathering reflects prolonged exposure to socioeconomic disadvantage in the U.S., then we should observe increasing Mexican-American IMR ratios (relative to Mexican-immigrants) with age. The results provided in Table 4 and in Figure 4 show that whereas the Mexican immigrant maternal age specific IMRs are 13 to 22 percent lower than those of Mexican Americans, there is no evidence that the maternal age-specific rate ratios increase with age. These patterns remain largely the same after adjusting for risk factors. In fact, there is a tendency toward a slightly decreasing gap in the adjusted rates between the Mexican-origin populations with age. In summary, while maternal age-specific IMR differentials between Mexican Americans and Mexican immigrants are significant, there is no evidence of increasing within-Mexican-origin disparity with age. However, we lack information on age of migration that is necessary for a more complete assessment of differential weathering.

Figure 4.

IMR (per 1,000): Mexican American maternal age-specific IMR (solid line) compared to Mexican immigrant IMR (dashed line) with 95% point-wise confidence intervals (dotted lines).

Thus far, we have shown that the relative survival disadvantage for infants born to older Mexican-origin women remains after adjustment for selected risk factors, but that nativity differences within the Mexican-origin population are relatively constant over the maternal age range. Given the limits of our data which uses nativity as a gauge of cumulative exposure to U.S. social conditions, there is no evidence that Mexican-Americans experience differential worsening with increasing maternal age—in terms of higher IMRs relative to Mexican immigrants—as might be expected under a weathering hypothesis. Next we consider possible factors that can account for the higher IMRs of older Mexican-origin women relative to non-Hispanic white women.

Relative Differences at Older Ages

Although comparisons of the Mexican-origin and non-Hispanic white populations provide evidence of differential decline in infant survival with advanced maternal age, we might question if the overall observed and predicted patterns simply reflect the relatively lower infant mortality accruing to selectively-advantaged non-Hispanic white women who give birth at older ages. That is, the question becomes not whether Mexican-origin women are experiencing more unfavorable outcomes with age, but whether they are being fairly compared to the reference population.

We observe from Table 1 and Figure 1 that non-Hispanic white women are more likely than their Mexican-origin counterparts to bear children at older ages. Table 3 and Figure 3 show that older non-Hispanic white women are less likely to be unmarried and less likely to have low educational attainment when compared to Mexican-origin women of the same age. Table 5 provides the joint distribution of education and marital status for non-Hispanic white and Mexican-origin mothers age 25 and older. We see that non-Hispanic white women are more likely to be married when compared to Mexican-origin women of the same age (89% vs. 73%). Married women in this age group also tend to be better educated than their unmarried counterparts, with 64% of non-Hispanic white women and 22% of Mexican-origin women in this age group completing 13 or more years of schooling. These better-educated married women represent an advantaged group who are considerably more likely to possess the socioeconomic resources to obtain adequate health care services and are likely to have additional sources of material and social support afforded by marriage. Given the existing socioeconomic disparities between the Mexican-origin and non-Hispanic white populations in this age group, we might ask to what extent are the relative infant mortality differentials at older maternal ages an artifact of differences in the socioeconomic composition of these groups, and particularly, the prevalence of relatively advantaged non-Hispanic whites in this segment of the maternal age distribution?

Table 5.

IMRs and Rate Ratios: Mothers Age 25 and Older by Education and Marital Status

| Years of Schooling | MO-US | RR | MO-FB | RR | NHW-US | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | IMR | % | IMR | % | IMR | ||||

| Married | 0–12 Years | 38.7% | 6.05 | 1.019 | 61.8% | 4.83 | 0.814 * | 25.0% | 5.93 |

| 13+ Years | 34.8% | 4.63 | 1.146 * | 10.7% | 4.32 | 1.068 | 64.2% | 4.04 | |

| All Levels | 73.5% | 5.38 | 1.176 * | 72.6% | 4.76 | 1.040 * | 89.2% | 4.57 | |

| Unmarried | 0–12 Years | 20.0% | 7.63 | 0.834 * | 25.1% | 5.28 | 0.577 * | 6.7% | 9.14 |

| 13+ Years | 6.5% | 6.67 | 1.018 | 2.3% | 5.54 | 0.845 * | 4.1% | 6.55 | |

| All Levels | 26.5% | 7.39 | 0.906 * | 27.4% | 5.30 | 0.650 * | 10.8% | 8.15 | |

| Overall | 100.0% | 5.91 | 1.192 * | 100.0% | 4.90 | 0.989 | 100.0% | 4.96 | |

| N | 667,548 | 1,540,659 | 12,325,121 | ||||||

Significantly different from 1.0 p < 0.05

Although the NCHS data lack detailed measures of socioeconomic status, it is possible to partially address this issue by treating maternal education as a proxy for socioeconomic status and compare overall infant mortality for women 25 and older by marital status and level of education. Table 5 shows that among married women with 12 or fewer years of schooling, the IMR among Mexican Americans is statistically equal to that of non-Hispanic whites (RR=1.019, 95% CI 0.968, 1.073), whereas the Mexican-immigrant IMR is 19% lower (RR=0.815, 95% CI 0.788, 0.841). Among married women with 13 or more years of schooling, the Mexican-immigrant IMR is statistically equal to that of non-Hispanic whites (RR=1.068, 95% CI 0.992, 1.150), but is nearly 15% higher (RR=1.146, 95% CI 1.079, 1.216) among Mexican Americans. The mortality of infants born to married women for all levels of schooling are about 18% higher for Mexican Americans (RR=1.176, 95% CI 1.131, 1.233) and 4% higher for Mexican immigrants (RR=1.04, 95% CI 1.011, 1.070) relative to non-Hispanic whites. These results suggest that the Mexican-origin relative infant mortality disadvantage at older maternal ages can be explained in part by compositional differences in maternal education across groups. That is, non-Hispanic white mothers in this age range are drawn disproportionately from a pool of higher-educated women whose infants face a much lower risk of death.

Infants born to unmarried women in general face a greater overall risk of dying within the first year. However, the infant mortality disadvantage associated with low education and single motherhood is considerably less in the Mexican-origin population when compared to non-Hispanic whites. In particular, infant mortality among unmarried women with 12 years of schooling or less is 17% lower among Mexican Americans (RR=0.834, 95% CI 0.781, 0.891) and is 42% lower among Mexican immigrants (RR=0.577, 95% CI 0.549, 0.606) relative to their non-Hispanic white counterparts, a finding that is consistent with earlier research (National Center for Health Statistics 2000). Among higher-educated unmarried mothers we find statistically equal IMRs for Mexican Americans (RR=1.018, 95% CI 0.903, 1.147) and IMRs that are 15% lower among Mexican immigrants (RR=0.845, 95% CI 0.732, 0.976) relative to non-Hispanic whites.

These results suggest that the overall relative survival advantage of Mexican-origin infants among unmarried mothers reflects the higher mortality of infants born to less-educated, unmarried non-Hispanic white mothers. In general, we find that Mexican origin infants are not penalized by low maternal education and single motherhood nor are they advantaged by higher maternal education and marriage to the same extent as non-Hispanic whites, a finding consistent with research on birth outcomes (Scribner and Dwyer 1989; James 1993). We can speculate that lack of an observed negative effect of low maternal education and single motherhood may be due to offsetting factors, and in particular, by other mechanisms of social support and/or healthy behavior in Mexican-origin communities.

Discussion

This research examines infant mortality by maternal age, race/ethnicity, and nativity using the NCHS cohort-linked birth and infant death data for the years 1995–2002. Age-specific fertility patterns differ among the 4 sub-populations considered in this research, with the distribution of births skewed towards younger ages in the Mexican-origin and the non-Hispanic black populations. An analysis of maternal age-specific infant mortality rates reveals a distinct survival advantage for infants born to younger Mexican-origin mothers relative to non-Hispanic whites, which is consistent with the Hispanic epidemiological paradox. However, infants born to older Mexican-origin mothers experience a distinct survival disadvantage relative to non-Hispanic whites, which is consistent with a weathering explanation. Differences in population composition on key socioeconomic dimensions of marriage and education may partially explain this maternal-age crossover.

Given the association between infant survival and maternal health, differential infant survival within the Mexican-origin population suggests that longer exposure to social conditions in the U.S. undermines the health of mothers who, in general, seem to have more favorable health endowments than their non-Hispanic white counterparts as evidenced by the relatively lower rates of infant mortality at younger ages. Our subsequent analysis adjusts maternal age-specific mortality rates for a number of known risk factors to yield predicted mortality rates for hypothetical low-risk populations, which are then compared. We find that the maternal age Mexican-origin infant mortality crossover described above persists after adjusting for risk factors.

Our findings are consistent with the conceptual framework of weathering (Geronimus 1992) insofar as: (1) relatively higher mortality is experienced by Mexican-Americans compared to Mexican immigrants over the entire maternal age range, (2) the fitted mortality rates for infants born to older Mexican-origin women are not adjusted downward to the extent of those of non-Hispanic whites, suggesting that factors not measured in these data are responsible for the relative survival disadvantage of these infants, and (3) Mexican immigrant women tend to have lower prevalence of maternal risk factors at older ages than Mexican-American women. On the other hand, we find no evidence of a growing within-Mexican-origin gap in IMR with increasing maternal age, which provides somewhat less support for a weathering explanation of infant mortality differences. However, data limitations preclude any definitive conclusions about the actual impact of exposure on maternal health and infant mortality. The consistency of the within-Mexican-origin gap also implies less salience of the salmon-bias explanation, which would attribute the lower infant mortality of Mexican immigrant infants to health selection. For example, if the likelihood of return migration is higher for older, less healthy, pregnant Mexican immigrant women, this would produce a selectively-healthier population of older Mexican immigrant mothers in the U.S. If this occurs on a large enough scale, we would expect to observe even lower IMRs at older ages among Mexican immigrants relative to Mexican Americans. However, this scenario is inconsistent with the converging patterns shown in Table 4 and Figure 4.

An important area of further research will be to inform about possible factors contributing to the relative survival disadvantage of infants born to older Mexican-origin women. The NCHS data lack measures of acculturation and duration of residence in the U.S., and they contain limited measures of socioeconomic status, and other important factors. However alternative data sources may offer insight into mechanisms underlying the apparent erosion of the Mexican-origin survival advantage at older maternal ages, perhaps by focusing on birth outcomes as proximate determinants.

The Hispanic infant mortality paradox has been the subject of a great deal of debate, with explanations that focus on immigrant selectivity (Franzizi et al. 2001; Markides and Eschbach 2005), the positive role of Hispanic culture (Franzizi et al. 2001; Scribner 1996), and data quality (Palloni and Morenoff 2001; Hummer et al. 2007; Turra and Elo 2008). While it is not possible to evaluate all of these explanations with the limited measures available in the NCHS data, recent research using these data provides strong evidence against the data-quality explanation (Hummer et al. 2007). This leaves positive selection and positive cultural characteristics as possible explanations for the lower IMRs of Mexican Americans and Mexican immigrants at younger maternal ages. The protective cultural attributes of Mexican-origin people that have been identified in past research include, lower rates of smoking and alcohol use, better nutrition, and stronger family ties when compared to non-Hispanic whites (Williams 1986). Past research has found support for the acculturation hypothesis (Cobas et al. 1996) in the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (HHANES). In particular, this research found that Mexican-origin women who maintained Mexican-oriented cultural values, beliefs, practices, and lifestyles, experienced lower rates of low birth weight (infant birth weights < 2500g) than their counterparts with a US-orientation. Other studies have found that nativity status is associated with low-weight birth rates within the Hispanic population (Williams 1986; Becerra et al. 1991), with Mexican Americans facing higher rates than Mexican immigrants.

In contrast to past studies, we provide detailed comparisons of maternal age-specific infant mortality. The finding that Mexican Americans and Mexican immigrants have consistently lower IMRs than non-Hispanic whites and blacks at younger maternal ages is a new pattern and is suggestive of the importance of selectivity and/or culture as explanations for their lower rates relative to other groups. Our finding of distinct patterns for Mexican Americans and Mexican immigrants is consistent with past findings regarding the possible role of acculturation. An important area of future research will be to understand what the specific mechanisms are, and why younger Mexican-origin women have such positive outcomes in the context of their risk profiles, which, in turn, could provide important clues regarding the reduction of infant mortality among non-Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic blacks.

Footnotes

The author gratefully acknowledges the support for this research provided by NICHD Grant NO. R01 HD049754 and would like to thank the editor, three anonymous reviewers, W. Parker Frisbie, Robert A. Hummer, Richard G. Rogers, Sarah McKinnon, and Jiwon Jeon for their helpful comments and suggestions. An earlier version of this article was presented at the annual meeting of the Population Association of America in Washington, D.C., March 31–April 3, 2011.

Asymptotic variances computed under alternative distributional assumptions yielded nearly identical interval estimates.

This is also interpreted as the non-Hispanic white IMR subject to the Mexican-American maternal age distribution. Here we note that the expected IMR of non-Hispanic whites would be statistically higher than the observed IMR under the Mexican-American maternal age distribution.

This is also interpreted as the non-Hispanic white IMR subject to the maternal age-specific mortality rates of Mexican Americans. Here we note that the expected mortality of non-Hispanic white infants would not be significantly different under this scenario.

Similarly, non-Hispanic white infants would have an insignificant survivor advantage if they were to experience the maternal age-specific infant mortality rates of Mexican Americans.

The total differential is p11– p22. The component due to differences in age structures is p11 – p21 and the component due to differences in age specific rates is p21 – p22, where pjj′ (j = 1,2 j′ =1,2) is the corresponding element in P.

Although birth outcomes such as low birth weight and short gestation are the most significant proximate determinants of infant mortality, these outcomes are generally associated with the maternal risk factors outlined above—especially smoking and utilization of prenatal care. Therefore, we do not include birth outcomes among the risk factors. However, the relationship between birth outcomes and maternal age deserves a closer examination in future research.

Coefficients are interpreted as logs of rates or differences in log rates and the exponentiated coefficients are interpreted as rates and rate ratios under this specification.

Sensitivity analysis was carried out by estimating models that excluded the missing data. This does not change the general pattern of predictions of rates and does not alter the conclusions.

Bibliography

- Abraido-Lanza AF, Dohrenwend BP, Ng-Mak DS, Turner JB. The Latino mortality paradox: A test of the “salmon bias” and healthy migrant hypotheses. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89:1543–1548. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.10.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht SL, Clarke LL, Miller MK, Farmer FL. Predictors of Differential Birth Outcomes among Hispanic Subgroups in the United States: The Role of Maternal Risk Characteristics and Medical Care. Social Science Quarterly. 1996;77:407–433. [Google Scholar]

- Althauser RP, Wigler M. Standardization and Component Analysis. Sociological Methods and Research. 1972;1:97–135. [Google Scholar]

- Becerra J, Hogue C, Atrash H, Perez N. Infant Mortality among Hispanics: A Portrait of Heterogeneity. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1991;265:217–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brillinger DR. The Natural Variability of Vital Rates and Associated Statistics. Biometrics. 1986;42:693–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos M, Palloni A. Maternal and Infant Health of Mexican Immigrants in the USA: The Effects of Acculturation, Duration, and Selective Return Migration. Ethnicity & Health. 2010;15:377–396. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2010.481329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho YT, Frisbie WP, Hummer RA, Rogers RG. Nativity, Duration of Residence and the Health of Hispanic Adults in the United States. International Migration Review. 2004;38:184–221. [Google Scholar]

- Cobas JA, Balcazar H, Benin MB, Keith VM, Chong Y. Acculturation and Low-Birthweight Infants among Latino Women: A Reanalysis of HHANES Data with Structural Equation Models. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:394–396. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.3.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das Gupta P. Standardization and Decomposition of Rates: A User’s Manual. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Elo IT, Preston SH. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Mortality at Older Ages. In: Martin LG, Soldo BJ, editors. Racial and Ethnic Differences in the Health of Older Americans. Chapter 2. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997. pp. 10–42. [Google Scholar]

- Elo IT, Turra CM, Kestenbaum B, Ferguson BR. Mortality among elderly Hispanics in the United States: Past evidence and new results. Demography. 2004;41:109–128. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo IT, Mehta NK, Huang C. Disability among Native Born and Foreign Born Blacks in the United States. Demography. 2011;48:241–265. doi: 10.1007/s13524-010-0008-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch BK, Hummer RA, Kolody B, Vega WA. The Role of Discrimination and Acculturative Stress in Physical Health of Mexican-Origin Adults. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Science. 2001;23:399–429. [Google Scholar]

- Finch BK, Vega WA. Acculturation Stress, Social Support, and Self-Rated Health among Latinos in California. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2003;5:109–115. doi: 10.1023/a:1023987717921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes D, Frisbie WP. Spanish Surname and Anglo Infant Mortality: Differentials Over a Half-Century. Demography. 1991;28:639–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzini L, Ribble JC, Keddie AM. Understanding the Hispanic Paradox. Ethnicity and Disease. 2001;11:496–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freide A, Baldwin W, Rhodes P, et al. Young Maternal Ages and Infant Mortality: The Role of Low Birth Weight. Public Health Reports. 1987;102:192–199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisbie WP, Forbes D, Hummer RA. Hispanic Pregnancy Outcomes: Additional Evidence. Social Science Quarterly. 1998;79:149–169. [Google Scholar]

- Frisbie WP, Song SE. Hispanic Pregnancy Outcomes: Differences Over Time and Current Risks. Policy Studies Journal. 2003;1:237–52. [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT. Effects of Race, Residence, and Prenatal Care on the Relationship of Maternal Age to Neonatal Mortality. American Journal of Public Health. 1986;76:1461–1421. doi: 10.2105/ajph.76.12.1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT. The Weathering Hypothesis and the Health of African-American Women and Infants: Evidence and Speculations. Ethnicity and Disease. 1992;2:207–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geronimus AT. Black/White Differences in the Relationship of Maternal Age to Birthweight: A Population-Based Test of the Weathering Hypothesis. Social Science and Medicine. 1996;42:589–97. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00159-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MM. Assimilation in American Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Guendelman S. Immigrants May Hold Clues to Protecting Health During Pregnancy. In: Jamner MS, Stokols D, editors. Promoting Human Wellness: New Frontiers for Research, Practice, and Policy. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2000. pp. 222–257. [Google Scholar]

- Hummer RA, Powers DA, Pullum SG, Gossman GL, Frisbie WP. Paradox Found (Again): Infant Mortality among the Mexican Origin Population in the United States. Demography. 2007;44:441–457. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummer RA, Benjamins M, Rogers RG. Race/Ethnic Disparities in Health and Mortality among the Elderly: A Documentation and Examination of Social Factors. In: Anderson N, Bulatao R, Cohen B, editors. Critical Perspectives on Racial and Ethnic Differences in Health in Late Life. Chapter 3. Washington, DC: National Research Council; 2004. pp. 53–94. [Google Scholar]

- Hummer RA, Biegler M, DeTurk P, Forbes D, Frisbie WP, Hong Y, Pullum SG. Race/Ethnicity, Nativity, and Infant Mortality in the United States. Social Forces. 1999;77:1083–1118. [Google Scholar]

- James SA. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Infant Mortality and Low Birth Weight: A Psychosocial Critique. Annals of Epidemiology. 1993;3:130–136. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(93)90125-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasso G, Massey DS, Rosenzweig MR, Smith JP. Immigrant Health: Selectivity and Acculturation. In: Anderson NB, Bulatao RA, Cohen B, editors. Critical Perspectives on Racial and Ethnic Differences in Health in Late Life. chapter 7. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2004. pp. 227–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaestner R, Pearson JA, Keene D, Geronimus AT. Stress Allostatic Load, and the Health of Mexican Immigrants. Social Science Quarterly. 2009;90:1089–1111. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00648.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa EM. Components of a Difference between Two Rates. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1955;50:1168–1194. [Google Scholar]

- Kotelchuck M. An Evaluation of the Kessner Adequacy of Prenatal Care Index and a Proposed Adequacy of Prenatal Care Utilization Index. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84:1414–1420. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.9.1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landale NS, Oropesa RS, Gorman BK. Migration and Infant Death: Assimilation or Selective Migration among Puerto Ricans. American Sociological Review. 2000;65:888–909. [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y, Cooper R, Cao G, Durazo-Arvizu R, Kaufman J, Luke A, McGee D. Mortality Patterns Among Adult Hispanics: Findings from the NHIS, 1986–1990. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:227–32. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.2.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan J. Social Conditions as Fundamental Causes of Disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;35(extra issue):80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markides KS, Coreil J. The Health of Hispanics in the Southwestern United States: An Epidemiologic Paradox. Public Health Reports. 1986;101:253–265. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markides KS, Eschbach K. Aging, Migration and Mortality: Current Status of Research on the Hispanic Paradox. Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 2005;60B(Special Issue II):68–75. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.special_issue_2.s68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot MG, Adelstein AM, Bulusu L. Lessons from the Study of Immigration Mortality. Lancet. 1984;1:1455–1457. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91943-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews TJ, MacDorman MF. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2. Vol. 57. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2008. Infant Mortality Statistics from the 2005 Period Linked Birth/Infant Death Data Set. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey DS. Residential Segregation and Neighborhood Conditions in US Metropolitan Areas. In: Smelser NJ, Wilson WJ, Michell F, editors. America Becoming: Racial Trends and Their Consequences. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Seeman TE. Protective and Damaging Mediators of Stress: Elaborating and Testing the Concepts of Allostasis and Allostatic Load. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;896:30–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. 2002 Birth Cohort Linked Birth/Infant Death Data Set and Documentation. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2002. NCHS CD-ROM Series 20, No. 20a, issued January 2006. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. 2001 Birth Cohort Linked Birth/Infant Death Data Set and Documentation. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2001. NCHS CD-ROM Series 20, No. 19a, issued January 2005. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. 2000 Birth Cohort Linked Birth/Infant Death Data Set and Documentation. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. NCHS CD-ROM Series 20, No. 18a, issued January 2004. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2000, with adolescent health chartbook. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. 1999 Birth Cohort Linked Birth/Infant Death Data Set and Documentation. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1999. NCHS CD-ROM Series 20, No. 17a, issued May 2003. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. 1998 Birth Cohort Linked Birth/Infant Death Data Set and Documentation. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1998. NCHS CD-ROM Series 20, No. 16a, issued April 2002. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. Birth Cohort Linked Birth/Infant Death Data Set and Documentation. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1997. NCHS CD-ROM Series 20, No. 15a, issued August 2000. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. 1996 Birth Cohort Linked Birth/Infant Death Data Set and Documentation. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1996. NCHS CD-ROM Series 20, No. 14a, issued September 1999. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics. 1995 Birth Cohort Linked Birth/Infant Death Data Set and Documentation. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1995. NCHS CD-ROM Series 20, No. 12a, issued November 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Palloni A, Arias E. Paradox Lost: Explaining the Hispanic Adult Mortality Advantage. Demography. 2004;41(3):385–415. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palloni A, Ewbank DC. Selection Processes in the Study of Racial and Ethnic Differentials in Adult Health and Mortality. In: Anderson NB, Bulatao RA, Cohen B, editors. Critical Perspectives on Racial and Ethnic Differences in Health in Late Life. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2004. pp. 171–226. chapter 6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palloni A, Morenoff JD. Interpreting the Paradoxical in the Hispanic Paradox. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2001;954:140–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb02751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portes A. Children of Immigrants: Segmented Assimilation and its Determinants. In: Portes A, editor. The Economic Sociology of Immigration: Essays on Networks, Ethnicity, and Entrepreneurship. New York, NY: Russell Sage; 1995. pp. 248–279. [Google Scholar]

- Portes A, Zhou M. The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and its Variants among Post-1965 Immigrant Youth. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1993;530:75–98. [Google Scholar]

- Poston DL, Dan H. Fertility Trends in the United States. In: Peck DL, Hollingsworth JS, editors. Demographic and Structural Change: The Effects of the 1980s on American Society. Westport, CT: Greenwood; 1996. pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers RG. Ethnic Differences in Infant Mortality, Fact or Artifact? Social Science Quarterly. 1989;70:642–649. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers RG, Hummer RA, Nam CB. Living and Dying in the U.S.A.: Behavioral, Health, and Social Differentials in Adult Mortality. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum E, Friedman S. Differences in the Locational Attainment of Immigrant and Native Born Households with Children in New York City. Demography. 2001;38:337–348. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg HM, Mauer JD, Sorlie PD, Johnson NJ, MacDorman MF, Hoyert DL, Spitler JF, Scott C. Vital and Health Statistics. 128. Vol. 2. National Center for Health Statistics; 1999. Quality of Death Rates by Race and Hispanic Origin: A Summary of Current Research. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saenz R. Ethnic Concentration and Chicano Poverty: A Comparative Approach. Social Science Research. 1997;26:205–228. [Google Scholar]

- Scribner R. Paradox as Paradigm—The Health Outcomes of Mexican Americans. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:303–305. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.3.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scribner R, Dwyer JH. Acculturation and Low Birthweight Among Latinos in the Hispanic HANES. American Journal of Public Health. 1989;79:1263–1267. doi: 10.2105/ajph.79.9.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, Singer BH, Rowe JW, Horwitz RI, McEwen BS. Price of Adaptation—Allostatic Load and Its Health Consequences. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1997;157:2259–2268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh GK, Siahpush M. All-cause and cause-specific mortality of immigrants and native born in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91:392–399. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.3.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh GK, Siahpush M. Ethnic-immigrant differentials in health behaviors, morbidity, and cause-specific mortality in the United States: An analysis of two national data bases. Human Biology. 2002;74:83–109. doi: 10.1353/hub.2002.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]