Abstract

An enzyme- and click chemistry-mediated methodology for the site-selective radiolabeling of antibodies on the heavy chain glycans has been developed and validated. To this end, a model system based on the prostate specific membrane antigen-targeting antibody J591, the positron-emitting radiometal 89Zr, and the chelator desferrioxamine has been employed. The methodology consists of four steps: (1) the removal of sugars on the heavy chain region of the antibody to expose terminal N-acetylglucosamine residues; (2) the incorporation of azide-modified N-acetylgalactosamine monosaccharides into the glycans of the antibody; (3) the catalyst-free click conjugation of desferrioxamine-modified dibenzocyclooctynes to the azide-bearing sugars; and (4) the radiolabeling of the chelator-modified antibody with 89Zr. The site-selective labeling methodology has proven facile, reproducible, and robust, producing 89Zr-labeled radioimmunoconjguates that display high stability and immunoreactivity in vitro (>95%) in addition to high selective tumor uptake (67.5 ± 5.0 %ID/g) and tumor-to-background contrast in athymic nude mice bearing PSMA-expressing subcutaneous LNCaP xenografts. Ultimately, this strategy could play a critical role in the development of novel well-defined and highly immunoreactive radioimmunoconjugates for both the laboratory and clinic.

Keywords: Positron emission tomography, click chemistry, strain-promoted click chemistry, glycans, glycoengineering, site-specific labeling, site-selective labeling, 89Zr, J591, prostate specific membrane antigen, prostate cancer, bioconjugation

Introduction

The remarkable selectivity, affinity, and stability of antibodies have made them extremely promising vectors for the delivery of diagnostic and therapeutic radioisotopes to tumors.1 Indeed, over the past two decades, antibodies bearing radionuclides ranging from 124I, 111In, and 64Cu for PET and SPECT imaging to 90Y, 177Lu, and 225Ac for radiotherapy have been successfully developed and translated to the clinic.2

One important limitation to the development and translation of radioimmunoconjugates, however, is the lack of site-selectivity in the radiolabeling of antibodies. The vast majority of antibody radiolabeling methods rely on reactions with amino acids, typically tyrosines for radioiodinations or lysines for radiometal chelator conjugations. Yet antibodies are, of course, very large molecules and thus possess multiple copies of each of these amino acid residues.3 Consequently, precise control over the exact molecular location of the radionuclides or radiometal-chelator complexes on the antibody is impossible. This lack of site-selectivity presents two principal complications to the development, validation, and clinical utilization of radioimmunoconjugates. First, without the ability to control the precise location of the radiolabel on the antibody, radioisotopes or radiometal chelates may become appended to the antigen-binding region of the antibody, adversely affecting the immunoreactivity of the construct. Second, without knowledge of the exact site of radiolabeling, the resultant radioimmunoconjugates remain somewhat inadequately chemically defined, which can pose a problem during basic scientific investigations and the preclinical development of radioimmunoconjugates. Further, while a number of non-site-specifically radiolabeled immunoconjugates are currently in use in the clinic, it is very likely that the development of site-specifically labeled conjugates that are well characterized and precisely chemically defined will prove valuable in the regulatory review and approval process.

Further, the lack of reproducibility offered by either direct labeling reactions or chelator conjugation strategies presents another troubling limitation to current strategies for the construction of radioimmunoconjugates. Given the non-site-selective nature of most radiolabeling methodologies, each new immunoconjugate must undergo extensive optimization in order to obtain a degree of labeling that strikes a suitable balance between the specific activity of the final radioimmunoconjugate and its immunoreactivity, a process which can be time-consuming, tedious, and costly. Further, labeling reagents themselves tend to be chemically unstable and subject to hydrolysis, thus requiring storage under inert atmospheres of argon or nitrogen.

In response to these issues, extensive efforts have been made to develop robust and reliable site-selective radiolabeling methodologies for antibodies.4–10 With few exceptions, these strategies rely on antibodies that have been specially engineered to bear either reactive thiol moieties or fusion proteins. These systems are creative and have proven successful; however, the use of genetically engineered antibodies adds undue layers of complexity and expense that hamper both the modularity and potential for clinical translation of the systems. To circumvent these issues, we have chosen to focus on a handle for site-specific antibody modification that has remained somewhat, though not completely, neglected in the development of radiolabeling strategies: the heavy chain glycans.

Immunoglobulin G antibodies (IgGs) contain a conserved N-linked glycosylation site on the CH2 domain of each heavy chain of the Fc region. N-linked oligosaccharides from a variety of different animal species show a heterogeneous mixture of biantennary complex-type oligosaccharides.11 In general, the number of sialylated oligosaccharides is significantly lower compared to the number of neutral sugar species, and high-mannose type oligosaccharides are absent (except in chickens).11 Although heterogeneous with respect to their core fucose, sialic acid, and galactose monomers, the majority of these biantennary glycans are composed of the G0, G1, or G2 isoforms (i.e. 0, 1, or 2 terminal galactose residues, respectively), with the specific ratio of isoforms dependent on species and physiological status.11 Since IgG glycans are located on the heavy chain Fc domain of the antibody — far from the antigen binding domains — they provide extremely attractive targets for site-selective chemical modification, and indeed, a number of conjugation methodologies have been developed to exploit this.12 For example, one fairly commonly-used modification strategy is predicated on the oxidation of vicinal alcohols on the sugar chains to aldehydes, followed by subsequent labeling via reductive amination or hydrazide condensation reactions. This methodology, however, requires prolonged exposure of the antibody to low pH and harsh redox conditions (e.g. treatment with periodate and cyanoborohydride) and can result in non-selective modifications to amino acid side chains in the antibody. These, of course, are seriously limiting factors, as the former can adversely affect the immunoreactivity of the antibody, and the latter can defeat the purpose of the site-selective modification strategy entirely.13

An alternative procedure for the site-selective modification of the IgG heavy chain glycans can be envisioned using a system based on unnatural UDP-sugar substrates and a substrate-permissive mutant of β-1,4-galactosyltransferase, GalT(Y289L), first designed, engineered, and expressed by Ramakrishnan and Qasba.14 This glycoengineering strategy has been used by a variety of researchers in a number of different settings, including the detection of post-translational modifications, the site-specific bioconjugation of immunoglobulins, the rapid identification of O-GlcNAc-glycosylated proteins in cell lystates, and the exploration of glycosylation patterns in the brain.15–24 In 2003, for example, Hsieh-Wilson and coworkers employed this system to selectively biotinylate proteins with post-translational O-GlcNAc modifications and then identify them using a horseradish peroxidase-based chemiluminescence reporter system.18 In more recent work, Qasba and coworkers have employed the substrate permissive GalT(Y289L) enzyme along with a C2-keto-galactose sugar in order to site-specifically modify both full IgGs and single chain antibodies with biotinylated and fluorescent reporter moieties.16, 17, 23, 25

Perhaps not surprisingly, the intersection of this glycoengineering technology and bioorthogonal click chemistry has already proven fertile ground.15, 26, 27 In 2008, for example, Clark, et al. used the azide-bearing UDP-N-acetylgalactosamine analog UDP-GalNAz (Scheme 1A) and an alkyne-modified fluorescent reporter to create a system for the detection, proteomic analysis, and cellular imaging of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins using canonical Cu-catalyzed azide-alkyne [3+2] cycloaddition click chemistry.15 Importantly, however, while the copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne click reaction has been shown to be selective and efficient, it is well-known that the presence of both copper(I) and copper(II) can damage proteins and thus interfere with the structure and function of enzymes, fluorescent proteins, and antibodies. Furthermore, and more specific to radiochemical applications, the Cu-catalyzed variant of this click reaction cannot be used in conjunction with radiometal chelators, as the presence of micromolar levels of Cu catalyst can interfere with the chelation chemistry of radiometals that are often present in extremely low concentrations.28 In recent years, the limitations of the Cu-catalyzed Huisgen cycloaddition reaction have been circumvented through the work of Bertozzi and Boons on the strain-promoted azide-alkyne click reaction: a selective, bioorthogonal, and catalyst-free ligation between an azide and a strained cyclic alkyne such as dibenzocyclooctyne.29–31 Interestingly, a large volume of work exists on the strain-promoted azide-alkyne reaction between cyclic alkynes and GalNAz-modified biomolecules. However, in these cases, GalNAz is not employed as a substrate for GalT(Y289L); rather, these applications exploit the promiscuity of the hexosamine biosynthetic pathway to metabolically tag O-GlcNAc-modified proteins with azides for subsequent labeling in vitro or in vivo.20, 29, 31–33

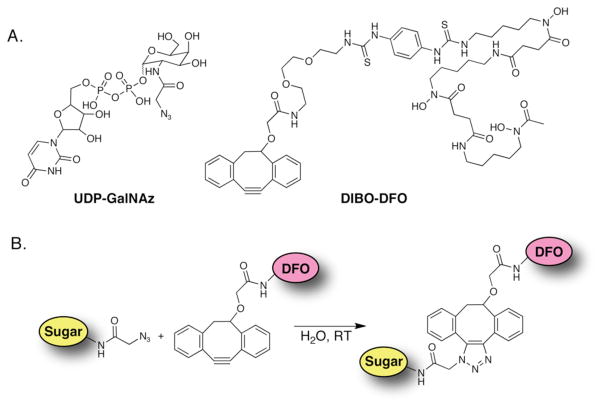

Scheme 1.

(A) Structures of UDP-GalNAz and DIBO-DFO; (B) Strain-promoted, catalyst-free click ligation between UDP-GalNAz and DIBO-DFO. DIBO = dibenzocyclooctyne; UDP = uridine-5′-diphosphate; GalNAz = N-azidozacetylgalactosamine; DFO = desferrioxamine.

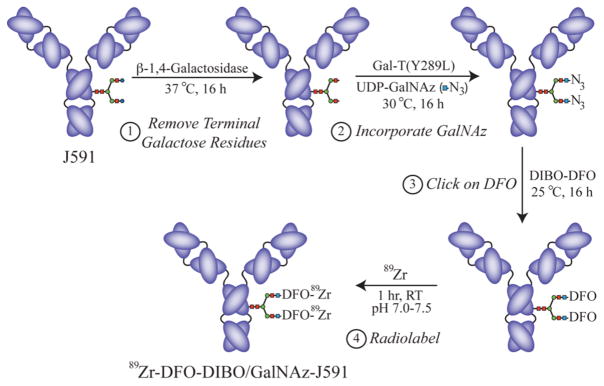

Herein, we present a methodology for the site-selective radiolabeling of antibodies utilizing a method that combines both enzyme-mediated GalNAz incorporation and bioorthogonal, strain-promoted, copper-free azide/alkyne cycloaddition click chemistry. The procedure consists of four simple steps: (1) the enzymatic removal of terminal galactose residues on the Fc domain to expose terminal GlcNAc residues; (2) the enzymatic incorporation of GalNAz monosaccharides onto the terminal GlcNAc residues; (3) the catalyst-free, strain-promoted click conjugation of novel chelator-modified dibenzocyclooctynes (DIBO) to the GalNAz residues; and (4) the radiolabeling of the chelator-modified construct with an appropriate radiometal (Schemes 1 and 2). Because all antibodies possess N-linked glycans located only on the heavy chain Fc region, this methodology is site-selective, and critically, unlike previous systems, requires no special antibody engineering. Further, we demonstrate here that this labeling method is mild, facile, highly reproducible, and that the sites of labeling are easily and rapidly characterized. Taken together, we believe that this modular and robust labeling methodology could play a critical role in the development of novel radioimmunoconjugates and at the same time provide considerable time and cost savings by eliminating cumbersome optimization and characterization steps.

Experimental Procedures

Reagents and General Procedures

All chemicals, unless otherwise noted, were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and were used as received without further purification. All water employed was ultra-pure (>18.2 MΩcm−1 at 25 °C), all DMSO was of molecular biology grade (>99.9%), and all other solvents were of the highest grade commercially available. Deimmunized J591 was obtained through MSKCC’s Clinical Research Department/Weill Cornell Medical College. All other antibody samples were obtained from Life Technologies, Inc. (Eugene, OR) and used as received. DIBO-NH2 (Click-IT® Amine DIBO Alkyne) was obtained from Life Technologies (Eugene, OR), and p-SCN-DFO was obtained from Macrocyclics, Inc. (Dallas, TX). The plasmid for GalT(Y289L) was obtained from Dr. P. K. Qasba, and the protein was obtained from Life Technologies, Inc., where it was expressed and purified according to published protocols.34 Click-IT® Alexa Fluor®-488 DIBO-Alkyne was obtained from Life Technologies, Inc. (Eugene, OR). All instruments were calibrated and maintained in accordance with standard quality-control procedures. UV-Vis measurements were taken on a Thermo Scientific NanoDrop 2000 Spectrophotometer. High resolution mass spectrometry measurements were performed on a Waters SYNAPT High Definition MS System (ESI-QTOF).

89Zr was produced at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center on an EBCO TR19/9 variable-beam energy cyclotron (Ebco Industries Inc., British Columbia, Canada) via the 89Y(p,n)89Zr reaction and purified in accordance with previously reported methods to yield 89Zr with a specific activity of 5.3 – 13.4 mCi/μg (195 – 497 MBq/μg).35 Activity measurements were made using a Capintec CRC-15R Dose Calibrator (Capintec, Ramsey, NJ). For accurate quantification of activities, experimental samples were counted for 1 min on a calibrated Perkin Elmer (Waltham, MA) Automatic Wizard2 Gamma Counter. Labeling of antibodies with 89Zr was monitored using silica-gel impregnated glass-fiber instant thin-layer chromatography paper (Pall Corp., East Hills, NY) and analyzed on a Bioscan AR-2000 radio-TLC plate reader using Winscan Radio-TLC software (Bioscan Inc., Washington, D. C.). All experiments performed on laboratory animals were performed according to a protocol approved by the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol 08-07-013).

Cell Culture

Human prostate cancer cell line LNCaP was obtained from the American Tissue Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) and maintained by weekly serial passage in a 5% CO2 (g) atmosphere at 37 °C. LNCaP cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 4.5 g/L glucose, 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate and 100 U/ml of penicillin and streptomycin. Cells were harvested using a formulation of 0.25% trypsin and 0.53 mM EDTA in Hank’s buffered salt solution without calcium or magnesium.

Xenograft Models

All experiments were performed under an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocol, and the experiments followed institutional guidelines for the proper and humane use of animals in research. Six to eight week-old athymic nude male (Hsd: Athymic Nude-nu) mice were obtained from Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN). Animals were housed in ventilated cages, were given food and water ad libitum, and were allowed to acclimatize for approximately 1 week prior to inoculation. LNCaP tumors were induced on the right shoulder by a subcutaneous injection of 5.0 × 106 cells in a 200 μL cell suspension of a 1:1 mixture of fresh media:BD Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA). The xenografts reached ideal size for imaging and biodistribution (~100–150 mm3) in approximately 4 weeks.

Synthesis of DIBO-DFO

To a suspension of 1-(4-isothiocyanatophenyl)-3-[6, 17-dihydroxy-7, 10, 18, 21-tetraoxo-27-(N-acetylhydroxylamino)-6, 11, 17, 22-tetrazaheptaeicosine]thiourea (p-SCN-Bn-desferrioxamine, 22 mg, 27 μmol,) and N-[2-[2-(2-aminoethoxy)ethoxy]ethyl]-2-[((11, 12-didehydro-5, 6-dihydrodibenzo[a,e]cycloocten-5-yl)oxy]acetamide (DIBO-NH2, 20 mg, 54 μmol) in 1.5 mL of anhydrous DMF was added triethylamine (75 μL, 0.54 mmol), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 48 hours. The resulting reaction mixture, which became a homogeneous solution, was added into 25 mL of ethyl acetate slowly over a 2 minute period while stirring vigorously at room temperature. The resulting precipitate was collected by filtration to give the desired product (DIBO-DFO, 24 mg, 80 % yield) as an off-white solid. TLC (silica gel, 15 % H2O in CH3CN): Rf = 0.59. 1H NMR (400 MHz, d6-DMSO): δ 1.29-1.12 (m, CH2, 8H), 1.43-1.32 (m, CH2, 4H), 1.58-1.44 (m, CH2, 8H), 1.96 (s, CH3, 3H), 2.32-2.20 (m, CH2, 4H), 2.67–2.53 (m, CH2, 4H), 3.77-2.67 (m, CH2, 22H), 3.93 (d, OCHH-C(=O)), 4.05 (d, OCHH-C(=O)), 4.16–4.20 (m, CH, 1H), 7.48-7.27 (m, ArH, 10H), 7.60 (d, ArH, 1H), 7.70 (d, ArH, 1H), 7.85-7.79 (m, NH, 2H), 9.60-9.35 (m, NH, 2H), 9.70-9.60 (m, N-OH, 3H). HRMS (ESI) calculated mass for C57H80N10O12S2+ (M+H+): 1161.4543: found mass: 1161.4911.

Synthesis of N-Azidoacetylgalactosamine (UDP-GalNAz)

UDP-GalNAz was synthesized in accordance with previously reported methods.32, 36

Site-Specific Antibody Modification with DFO-DIBO/GalNAz

Glycans Modification

J591 (1 mg, 8 mg/mL, in phosphate buffer saline [PBS], pH 7.4) was buffer exchanged into pre-treatment buffer (50 mM Na-phosphate, pH 6.0) using a micro-spin column prepared with P30 resin (Bio-Rad 732-6008, 1.5 mL bed volume). The column was first equilibrated with 50 mM Na-phosphate, pH 6.0 and centrifuged for 3 minutes at 850 × g. 125 μL J591 antibody was then added and centrifuged for 5 minutes at 850 × g. The resultant antibody solution was supplemented with 40 μL of β-1.4-galactosidase (from S. pneumonia [2 mU/μL], obtained from Life Technologies, Inc., Eugene, OR) and placed in an incubator at 37 °C overnight.

GalNAz Labeling

A buffer exchange of the sample into TBS reaction buffer (20 mM Tris HCl, 0.9% NaCl, pH 7.4) was performed using a micro-spin column prepared with P30 resin. After the buffer exchange, the antibody (600 μg in 300 μL TBS buffer) was combined with UDP-GalNAz (40 μL of a 40mM solution in H2O), MnCl2 (150 μL of a 0.1M solution), and Gal-T(Y289L) (1000 μL of 0.29 mg/mL in 50 mM Tris, 5 mM EDTA (pH 8)). The final solution contained concentrations of 0.4 mg/mL antibody, 10 mM MnCl2, 1 mM UDP-GalNAz, and 0.2 mg/mL Gal-T(Y289L) and was incubated overnight at 30 °C.

DIBO-DFO Ligation

The solution from the GalNAz labeling step was purified using six micro-spin columns prepared with P30 resin and TBS buffer (each micro-spin column received 250 μL of the GalNAz labeling solution). After centrifugation, the filtrates were combined to yield 1500 μL of antibody solution. Subsequently, 200 μL of DIBO-DFO solution (1.74 mg in 750 μL DMSO, 2 mM stock) was added to the combined filtrates, and this tube was incubated at 25 °C overnight.

Purification

After DIBO-DFO labeling, the completed antibody was purified via size exclusion chromatography (Sephadex G-25 M, PD-10 column, GE Healthcare) and concentrated using centrifugal filter units with a 50,000 molecular weight cut off (Amicon™ Ultra 4 Centrifugal Filtration Units, Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA) and phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4).

Non-specific Antibody Modification with DFO-NCS

J591 (2–3 mg) was dissolved in 1 mL of phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4), and the pH of the solution was adjusted to 8.8–9.0 with NaHCO3 (0.1 M). To this solution was added an appropriate volume of DFO-NCS in DMSO (5–10 mg/mL) to yield a chelator:mAb reaction stoichiometry of 6:1. The resultant solution was incubated with gentle shaking for 30 min at 37 °C. After 30 min, the modified antibody was purified using centrifugal filter units with a 50,000 molecular weight cut off (Amicon™ Ultra 4 Centrifugal Filtration Units, Millipore Corp., Billerica, MA) and phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4).37

SDS-PAGE Confirmation of Modification Sites

The N-glycans of J591 were GalNAz-tagged at the terminal GlcNAc residues with UDP-GalNAz using the β-galactosyltransferase mutant Gal-T(Y289L) (as described above). The azide groups were then clicked with DIBO-DFO or left unmodified. The N-glycans on the Fc of the heavy chain were then retained or removed from their asparagine residue attachment points via PNGase F treatment (see below). In addition, control, unmodified J591 was also included and either treated or left untreated with PNGase F. Mark12™ Unstained Standard (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) was used as a molecular weight standard. For gel analysis, antibodies were applied on NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gels and run in MOPS buffer. 200 ng antibody was applied per lane. After staining with SYPRO® Ruby Protein Stain, the gels were imaged with a FUJI FLA9000 scanner with an excitation of 473 nm and a 575LP filter.

PNGase F Treatment of Antibody

J591 antibody construct (1 μg) in 10 μL TBS was denatured with 0.5% SDS and 40 mM DTT by adding 17 μl H2O and 3 μL 10× Glycoprotein Denaturation Buffer (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and incubated at 90 °C for 10 min. For PNGase F treatment, 18 μl H2O, 6 μL 10% NP-40 and 6 μL 500 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5 (G7 reaction buffer from New England Biolabs) was added. Samples were split in half, and one aliquot was supplemented with 1 μl PNGase F (New England Biolabs) and incubated overnight at 37 °C. 12 μL were loaded per lane on a SDS gel for analysis (see above).

Radiolabeling of Antibody Constructs with 89Zr

For each antibody construct, 0.4–0.5 mg was added to 200 μL buffer (PBS, pH 7.4). [89Zr]Zr-oxalate (2000–2500 μCi) in 1.0 M oxalic acid was adjusted to pH 7.0–7.5 with 1.0 M Na2CO3. After the evolution of CO2(g) stopped, the 89Zr solution was added to the antibody solution, and the resultant mixture was incubated at room temperature for 1 h. After 1 h, the reaction progress was assayed using radio-TLC with an eluent of 50 mM EDTA, pH 5, and the reaction was quenched with 50 μL of the same EDTA solution. The antibody construct was purified using size-exclusion chromatography (Sephadex G-25 M, PD-10 column, GE Healthcare; dead volume = 2.5 mL, eluted with 500 μL fractions of PBS, pH 7.4) and concentrated, if necessary, with centrifugal filtration. The radiochemical purity of the crude and final radiolabeled bioconjugate was assayed by radio-TLC. In the ITLC experiments, the antibody construct remains at the baseline, while 89Zr4+ ions and [89Zr]-EDTA elute with the solvent front.

Immunoreactivity Measurements

The immunoreactivity of the 89Zr-DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591and 89Zr-DFO-NCS-J591 bioconjugates was determined using specific radioactive cellular-binding assays following procedures derived from Lindmo, et al.38, 39 To this end, LNCaP cells were suspended in microcentrifuge tubes at concentrations of 5.0, 4.0, 3.0, 2.5, 2.0, 1.5, and 1.0 × 106 cells/mL in 500 μL PBS (pH 7.4). Aliquots of either 89Zr-DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591 or 89Zr-DFO-NCS-J591 (50 μL of a stock solution of 10 μCi in 10 mL of 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS pH 7.4) were added to each tube (n = 4; final volume: 550 μL), and the samples were incubated on a mixer for 60 min at room temperature. The treated cells were then pelleted via centrifugation (3000 rpm for 5 min), resuspended, and washed twice with cold PBS before removing the supernatant and counting the activity associated with the cell pellet. The activity data were background-corrected and compared with the total number of counts in appropriate control samples. Immunoreactive fractions were determined by linear regression analysis of a plot of (total/bound) activity against (1/[normalized cell concentration]). No weighting was applied to the data, and the data were obtained in triplicate.

Stability Measurements

The stability of the 89Zr-DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591 and 89Zr-DFO-NCS-J591 bioconjugates with respect to radiochemical purity and loss of radioactivity from the antibody was investigated in vitro by incubation of the antibodies in human serum for 7 d at 37 °C. The radiochemical purity of the antibodies was determined via radio-TLC with an eluent of 50 mM EDTA pH 5.0. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Both final constructs, 89Zr-DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591 and 89Zr-DFO-NCS-J591, demonstrated >96% stability at 120 h.

Chelate Number

The number of accessible DFO chelates conjugated to each antibody was measured by radiometric isotopic dilution assays following methods similar to those described by Anderson, et al. and Holland, et al.40, 41

PET Imaging

PET imaging experiments were conducted on a microPET Focus rodent scanner (Concorde Microsystems). Mice bearing subcutaneous LNCaP (right shoulder) xenografts (100–150 mm3) were administered 89Zr-DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591 or 89Zr-DFO-NCS-J591 (10.2 – 12.0 MBq [275–325 μCi] in 200 μL 0.9% sterile saline) via intravenous tail vein injection (t = 0). Approximately 5 minutes prior to the PET images, mice were anesthetized by inhalation of 2% isoflurane (Baxter Healthcare, Deerfield, IL)/oxygen gas mixture and placed on the scanner bed; anesthesia was maintained using 1% isoflurane/gas mixture. PET data for each mouse were recorded via static scans at time points between 24 and 120 h. A minimum of 20 million coincident events were recorded for each scan, which lasted between 10–45 min. An energy window of 350–700 keV and a coincidence timing window of 6 ns were used. Data were sorted into 2-dimensional histograms by Fourier re-binning, and transverse images were reconstructed by filtered back-projection (FBP) into a 128 × 128 × 63 (0.72 × 0.72 × 1.3 mm) matrix. The image data were normalized to correct for non-uniformity of response of the PET, dead-time count losses, positron branching ratio, and physical decay to the time of injection but no attenuation, scatter, or partial-volume averaging correction was applied. The counting rates in the reconstructed images were converted to activity concentrations (percentage injected dose [%ID] per gram of tissue) by use of a system calibration factor derived from the imaging of a mouse-sized water-equivalent phantom containing 89Zr. Images were analyzed using ASIPro VM™ software (Concorde Microsystems).

Acute Biodistribution

Acute in vivo biodistribution studies were performed in order to evaluate the uptake of both 89Zr-DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591 and 89Zr-DFO-NCS-J591 in mice bearing subcutaneous LNCaP xenografts (right shoulder, 100–150 mm3, 4 weeks post inoculation). Tumor-bearing mice were randomized before the study and were warmed gently with a heat lamp for 5 min before administration of the appropriate 89Zr-antibody construct (0.55 – 0.75 MBq [15–20 μCi] in 200 μL 0.9% sterile saline, 4–6 μg) via intravenous tail vein injection (t = 0). Animals (n = 4 per group) were euthanized by CO2(g) asphyxiation at 24, 48, 72, and 96 h post-injection. In addition, to probe the ability to saturate the biomarker, an additional cohort of animals were administered 89Zr-conjugates with dramatically lowered specific activity — achieved by co-injection of the standard dose of 89Zr-labeled J591 mixed with 300 μg of the cold, unlabeled J591 conjugate — and euthanized at 72 h post-injection. After asphyxiation, 13 tissues (including tumor) were removed, rinsed in water, dried in air for 5 min, weighed, and counted in a gamma counter calibrated for 89Zr. Counts were converted into activity using a calibration curve generated from known standards. Count data were background- and decay-corrected to the time of injection, and the %ID/g for each tissue sample was calculated by normalization to the total activity injected.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by the unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test. Differences at the 95% confidence level (P < 0.05) were considered to be statistically significant.

Results and Discussion

System Design

For the study at hand, a model system was constructed using the anti-prostate selective membrane antigen (PSMA) antibody J591, the positron-emitting radioisotope 89Zr, and the acyclic chelator desferrioxamine (DFO).42, 43 Over the course of the past five years, 89Zr has emerged as an extremely promising radionuclide for antibody-based imaging, primarily due to the advantageous match between the relatively long physical half-life of the radiometal (t1/2 = 3.2 days) and the multi-day in vivo pharmacokinetic profile of many antibodies but also resulting from the significant stability of the chelation complex the radiometal forms with its preferred siderophore-derived chelator, DFO. Initially developed by Bander, et al., J591 is a monoclonal antibody that targets an extracellular epitope of PSMA, a 100-kDa, type II transmembrane glycoprotein that is one of the best-characterized oncogenic markers for prostate cancer.44, 45 Indeed, the expression of PSMA has been shown to exhibit a positive correlation with increased tumor aggression, metastatic spread, and the development of castrate resistance or resistance to hormone-based therapies.46 Given these critical relationships, PSMA has been a promising target for diagnostic and therapeutic agents for over a decade. Indeed, agents ranging from small molecules to antibodies (e.g. 111In-7E11, which targets an intracellular epitope of the antigen) have been developed to target PSMA, with varying results.47–49 J591, however, has consistently remained one of the most promising PSMA-targeted vectors, and a range of clinical trials have been reported employing J591 radiolabeled with 131I, 177Lu, or 90Y for β-therapy, 225Ac or 213Bi for α-therapy, and 111In for SPECT.50–55 Ultimately, this particular collection of components was chosen for the model system not only because both the biology of J591 and the radiochemistry of 89Zr are extremely well-characterized but also because the system has tremendous clinical relevance, as non-site-selectively labeled 89Zr-DFO-NCS-J591 is currently being translated to the clinic at MSKCC for patients with prostate cancer.42, 56

Synthesis and Characterization

The first step in the investigation was the synthesis of the two basic molecular components of the system (Scheme 1). While a number of different cyclooctynes have been successfully synthesized and employed in strain-promoted click chemistry, dibenzocyclooctyne (DIBO) has been shown to strike an excellent balance between stability and reactivity and, crucially, boasts variants with convenient conjugation handles that are commercially available. Therefore, the cyclooctyne component of this system, DIBO-DFO, was synthesized via a facile isothiocyanate coupling between commercially-available SCN-DFO and a DIBO variant bearing a pendant amine.30 For the other half of the system, the activated, azide-bearing monosaccharide, UDP-GalNAz, was synthesized according to published literature procedures.32, 36 Following synthesis, both precursors were extensively chemically characterized by a variety of spectroscopic methods, including UV-Vis, 1H-NMR, and high resolution mass spectrometry.

With these components in hand, the antibody was then site-selectively labeled with the chelator DFO in three steps (Scheme 2). First, the antibody (1 mg) was incubated with β-1,4-galactosidase for 16 h at 37 °C in sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) in order to expose the terminal GlcNAc sugar residues. Second, the antibody was incubated with UDP-GalNAz and a modified, substrate permissive β-Gal-T1 enzyme, Gal-T(Y289L), for 16 h at 30 °C in order to attach the azide-modified sugars to the heavy chain glycans. And finally, the GalNAz-modified antibody (400 μg in 1 mL TBS buffer) was incubated with DIBO-DFO (200 μL of a 2 mM solution in DMSO) for 16 h at RT in order to attach the chelator to the antibody via strain-promoted, catalyst-free click chemistry. This final step will yield two very slightly different regioisomers based on the triazole ring; however, it is extremely unlikely that such small molecular variations will have any significant in vitro or in vivo effect on the behavior of a 150,000 Dalton macromolecule (see Supporting Information Figure S1).

Scheme 2.

Four step strategy for the site-selective, enzyme- and click chemistry-mediated radiolabeling of antibodies on the heavy chain glycans.

After this final step, purification via size exclusion chromatography yielded the site-selectively modified DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591 in 49 ± 5 % yield over three steps (n = 3). For the sake of comparison, J591 was also non-site-selectively labeled with DFO via incubation of J591 with DFO-NCS (Macrocyclics, Inc.) in carbonate buffer for 1 h at 37 °C, followed by purification via size exclusion chromatography to obtain DFO-NCS-J591 in 86 ± 2% yield (n = 3). It is important to note that while the site-selective modification strategy described here is admittedly somewhat lengthy, especially compared to the non-specific labeling methodology, the antibody is subjected to relatively mild conditions throughout the procedure.

The ubiquitous nature of heavy chain glycans on antibodies makes this methodology especially promising as a universal strategy for antibody modification, and indeed, additional experimentation confirmed that the system is both reproducible and robust. Over the course of six trials, the number of accessible chelates appended per J591 antibody construct was shown to be 2.8 ± 0.2 using a radiometric isotopic dilution assay. In parallel, a gel-based fluorescence assay was used as an alternative method to determine the number of GalNAz residues incorporated per J591 antibody. In this case, the J591 antibody was site-specifically modified with GalNAz and clicked with an AlexaFluor® 488-labeled variant of DIBO (Click-iT® DIBO-Alexa Fluor® 488, Life Technologies, Eugene, OR). Subsequent analysis of these samples via SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis revealed a degree of labeling (DOL) of 2.7 ± 0.2 GalNAz residues per antibody (n = 3, see Supporting Information Methods, Figure S2, and Table S1). Clearly, these two disparate but reliable assays produced statistically identical results for the number of chelators and the number of GalNAz resides per antibody, data that strongly suggests that the strain-promoted click reaction is nearly quantitative and that correlates very well with previously published data demonstrating quantitative labeling using this reaction (see Supporting Information Figure S2)

To illustrate the broad applicability of this system for the labeling of a variety of different antibodies, a panel of 13 antibodies including representatives from the IgG1, IgG2, and IgG3 families of immunoglobulins were site-specifically modified with GalNAz and clicked with a DIBO compound modified with the fluorophore AlexaFluor® 488 (Click-iT® DIBO-Alexa Fluor® 488, Life Technologies, Eugene, OR). In this case, a fluorophore-modified DIBO variant was again employed in place of its DFO-modified cousin because the gel-based method of determining degree of labeling is more reliable, more facile, and — due to the lack of 89Zr — much less expensive than the isotopic dilution technique. Over the course of labeling 13 different antibodies, the degree of labeling was shown to be 3.3 ± 0.3 fluorophores/antibody, with no antibody construct bearing fewer than 2.7 fluorophores, and no conjugate containing more than 3.8 (see Supporting Information Table S1). The antibody-to-antibody reproducibility range of ± 0.3 labels is unprecedented when compared to any other existing chemical antibody conjugation system that does not require genetic manipulation of the antibody.

With regard to the number of chelates per antibody, it has been well-established that IgG antibodies have, on average, two biantennary glycans, making the maximum number of possible chelates per antibody four. However, as described above, our modification of J591 resulted in 2.8 ± 0.2 chelates/antibody, and our fluorescence labeling experiments across a variety of antibodies resulted in an average degree of labeling of 3.3 ± 0.3. There are several factors that can account for the sub-maximal labeling. First, our data shows that the efficiency of the chemical click reaction with DFO-DIBO is quantitative (vide supra and see Supporting Information Figure S2). Therefore, variation in the DOL is likely due to the primary enzymatic reactions. Along these lines, we know that a fraction of the terminal GlcNAc residues are inaccessible from the outset because we did not remove terminal sialic acids by using sialidase in conjunction with β-galactosidase. Although sialic acid content on IgGs is generally around 10% (% residue/antibody glycan), it has been shown that in some cases, sialic acid content can reach as high as 20% or more and is dependent on numerous factors including animal species, expression cell type, and cell culture conditions. (13,49,50) Typically, however, we have only seen only a 10% or less increase in the DOL when sialidase is used in conjunction with β-galactosidase (data not shown). Secondly, it is possible the access of the Gal-T(Y298L) enzyme to some of the terminal GlcNAc residues is restricted due to steric hindrance. Warnock, et al. have shown that conversion of G0 to G1 isoforms using a wild-type GalT proceeded much faster than conversion of the G1 to G2 isoforms and that subsequently the labeling efficiency of the enzyme was improved by increasing the concentration of antibody in the reaction.57 Finally, a lack of GalNAz incorporation into the antibody glycans may result from the absence of terminal GlcNAc residues due to N-glycan truncation or even glycosylation site vacancy.58 We are currently in the process of performing both CE and MS-based glycan analysis studies that will better characterize the terminal sugar configurations both before and after labeling. In any case, we demonstrate here a degree of labeling of 2.8 ± 0.2 in the case of DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591 and an average antibody-to-antibody DOL of 3.3 ± 0.2. If we take into account an average sialic acid content of 10%, we can reproducibly account for greater than 90% of all available terminal GlcNAc residues with a click labeling efficiency of greater than 95%.

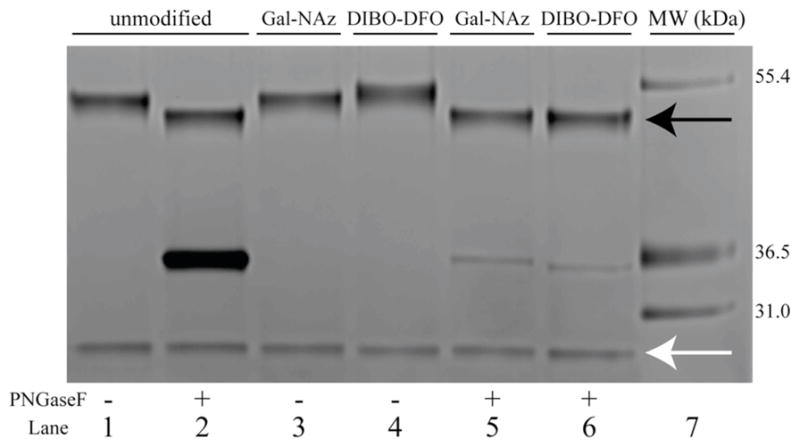

Returning to the DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591 system, SDS-PAGE electrophoresis experiments were run in order to further investigate the site-selectivity of the GalNAz/DIBO-DFO conjugation methodology. In these experiments, J591 that had either been left completely unmodified, modified only with GalNAz, or modified with GalNAz and subsequently clicked with DIBO-DFO were treated with PNGaseF, an amidase that cleaves at the site between the innermost GlcNAc residue and the asparagine residues of the antibody. As shown in the resulting gel (Figure 1), the heavy chains of all three antibody variants (upper bands, black arrow) were shifted to the same lower molecular weight after treatment with PNGaseF, confirming that the GalNAz and DFO modifications had been made site-selectively on the heavy chain N-linked glycans.

Figure 1.

SDS-PAGE of unmodified (lanes 1, 2), GalNAz-modified (lanes 3, 5), or DIBO-DFO-modified (lanes 4, 6) J591 antibody constructs either untreated (lanes 1, 3, 4) or treated (lanes 2, 5, 6) with PNGaseF. The black and white arrows indicate the antibody heavy chain and light chain, respectively, and the bands at 36.5 kDa are the result of excess PNGaseF enzyme.

Next, both the DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591 and DFO-NCS-J591 antibody conjugates were radiolabeled with 89Zr via incubation of the antibody (400–500 μg) with 89Zr (2.0 – 2.5 mCi) in PBS buffer at pH 7.0–7.5 for 1 h at RT, followed by purification with size exclusion chromatography. Both antibodies were labeled in >95% radiochemical yield and purified to >99% radiochemical purity, with final specific activities of 3.5 ± 0.2 mCi/mg and 3.4 ± 0.3 mCi/mg for 89Zr-DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591 and 89Zr-DFO-NCS-J591, respectively. In further characterization, isotopic dilution experiments employing non-radioactive Zr4+ determined that the number of accessible chelates per antibody for each variant was 2.8 ± 0.2 for DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591 and 3.1 ± 0.5 for DFO-NCS-J591. Further, in vitro immunoreactivity experiments using the PSMA-expressing LNCaP prostate cancer cell line revealed an average immunoreactive fraction of 0.95 ± 0.02 for DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591 and 0.91 ± 0.02 for DFO-NCS-J591. And finally, to assay the stability of the radiolabeled bioconjugates, both 89Zr-DFO-NCS-J591 and 89Zr-DFO-DIBO/GalNAZ-J591 were incubated in human serum for 7 d at 37 °C. Radio-TLC with an eluent of 50 mM EDTA (pH 5.0) performed over the course of the experiment clearly illustrated that both sets of conjugates were >96% stable after the incubation period. Clearly, these data indicate that the properties of the site-selectively labeled J591 are effectively identical to those of the conventionally, non-site-selectively labeled variant. It is further of note that in this case, the site-selective modification strategy does not result in a significant improvement in immunoreactivity over its non-site-selectively labeled cousin. Indeed, this is further confirmed by the work of Holland, et al., in which a non-site-specifically labeled variant of 89Zr-DFO-J591 was synthesized with a slightly higher number of chelates per antibody (3.9 ± 0.3 DFO/mAb) and a slightly increased specific activity of (4.91 ± 0.03 mCi/mg) without dramatically affecting immunoreactivity (0.95 ± 0.03).42 However, this is certainly a result of the robustness of the highly-optimized antibody employed in these model systems, J591. The true benefit of site-selective conjugation and radiolabeling is far more likely to be observed with less optimized constructs, and, as a result, efforts toward the application of this labeling methodology with less robust antibodies — i.e., antibodies with which the site-selective labeling methodology will confer a more significant advantage with regard to immunoreactivity — are currently underway.

With the synthesis, characterization, and in vitro testing complete, the next step of the investigation was to assay the effectiveness of 89Zr-DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591 in vivo. To this end, both acute biodistribution and PET imaging experiments were performed for both antibody constructs using athymic nude mice bearing subcutaneous, PSMA-expressing LNCaP prostate cancer xenografts.42 In the biodistribution experiments, athymic nude mice bearing subcutaneous LNCaP xenografts implanted in the right shoulder were injected via tail vein with either 89Zr-DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591 or 89Zr-DFO-NCS-J591 (15–20 μCi, 4–6 μg) and euthanized at 24, 48, 72, and 96 h post-injection, followed by the collection and weighing of tissues and the assay of the amount of 89Zr activity in each tissue (Tables 1 and 2, respectively). For both radioimmunoconjugates, high levels of selective uptake of the radiotracer are observed in the LNCaP xenografts, with the %ID/g increasing to maxima at 96 h of 67.6 ± 5.0 and 57.5 ± 5.3 for 89Zr-DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591 and 89Zr-DFO-NCS-J591, respectively. In terms of tumor-to-muscle activity ratios, 89Zr-DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591 yielded ratios of 12.2 ± 5.1, 28.6 ± 14.3, and 68.2 ± 26.9 at 48, 72, and 96 h, respectively, while 89Zr-DFO-NCS-J591 produced comparable values of 17.2 ± 9.2, 64.4 ± 27.0, and 38.1 ± 6.2 at the same three time points (see Supporting Information Tables S2 and S3).

Table 1.

Biodistribution data for 89Zr-DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591 versus time in mice bearing subcutaneous LNCaP xenografts (n = 4 for each time point). Mice were administered 89Zr-DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591 (0.55 – 0.75 MBq [15–20 μCi] in 200 μL 0.9% sterile saline) via tail vein injection (t = 0). For the 72 h time point, an additional cohort of animals were given 89Zr-DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591 with dramatically lowered specific activity (LSA), achieved by the coinjection of the standard dose of the 89Zr-labeled construct mixed with 300 μg of cold, unlabeled DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591.

| 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | 96 h | 72 h LSA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | 11.1 ± 4.5 | 7.2 ± 4.0 | 6.0 ± 1.6 | 2.9 ± 2.5 | 10.1 ± 1.9 |

| Tumor | 14.4 ± 2.5 | 28.2 ± 6.8 | 56.3 ± 5.1 | 67.6 ± 5.0 | 28.5 ± 6.8 |

| Heart | 4.6 ± 0.7 | 3.2 ± 1.2 | 3.1 ± 0.7 | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 3.2 ± 0.7 |

| Lung | 5.4 ± 2.5 | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 5.4 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 5.4 ± 1.0 |

| Liver | 10.3 ± 6.6 | 6.2 ± 4.6 | 5.1 ± 1.6 | 3.1 ± 0.9 | 4.7 ± 0.9 |

| Spleen | 11.1 ± 3.0 | 7.0 ± 5.7 | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 2.0 ± 0.7 | 3.3 ± 1.1 |

| Stomach | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.5 | 0.7 ± 0.2 |

| Large Intestine | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 1.2 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| Small Intestine | 2.4 ± 1.0 | 1.7 ± 1.3 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 1.0 | 1.4 ± 0.6 |

| Kidney | 5.0 ± 3.5 | 2.4 ± 1.2 | 2.6 ± 1.3 | 2.5 ± 1.2 | 3.9 ± 1.4 |

| Muscle | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1 ± 0.1.0 |

| Bone | 11.1 ± 6.6 | 10.3 ± 2.1 | 8.7 ± 0.8 | 7.4 ± 0.9 | 3.4 ± 1.4 |

| Skin | 3.1 ± 2.9 | 3.4 ± 1.6 | 3.1 ± 0.7 | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 5.0 ± 0.8 |

Table 2.

Biodistribution data for 89Zr-DFO-NCS-J591 versus time in mice bearing subcutaneous LNCaP xenografts (n = 4 for each time point). Mice were administered 89Zr-DFO-NCS-J591 (0.55 – 0.75 MBq [15–20 μCi] in 200 μL 0.9% sterile saline) via tail vein injection (t = 0). For the 72 h time point, an additional cohort of animals were given 89Zr-DFO-NCS-J591 with dramatically lowered specific activity (LSA), achieved by the coinjection of the standard dose of the 89Zr-labeled construct mixed with 300 μg of cold, unlabeled DFO-NCS-J591.

| 24 h | 48 h | 72 h | 96 h | 72 h LSA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood | 9.1 ± 5.3 | 7.4 ± 5.5 | 4.3 ± 4.9 | 7.9 ± 1.9 | 8.9 ± 0.5 |

| Tumor | 20.9 ± 5.6 | 30.7 ± 6.6 | 48.1 ± 9.3 | 57.5 ± 5.3 | 23.5 ± 11.1 |

| Heart | 4.7 ± 2.3 | 4.5 ± 1.7 | 2.6 ± 1.0 | 3.9 ± 1.1 | 2.7 ± 0.2 |

| Lung | 2.3 ± 0.8 | 3.4 ± 2.9 | 2.1 ± 1.3 | 6.3 ± 0.9 | 3.7 ± 1.9 |

| Liver | 6.1 ± 2.7 | 4.0 ± 1.3 | 3.8 ± 1.6 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | 5.6 ± 3.0 |

| Spleen | 5.7 ± 1.9 | 7.5 ± 5.6 | 3.9 ± 1.4 | 4.2 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.3 |

| Stomach | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.9 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.1 |

| Large Intestine | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.2 |

| Small Intestine | 2.4 ± 2.0 | 2.7 ± 1.2 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.4 |

| Kidney | 6.2 ± 0.9 | 4.9 ± 2.0 | 2.1 ± 1.1 | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 3.0 ± 0.9 |

| Muscle | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 1.8 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 3.2 ± 1.0 | 0.7 ± 0.3 |

| Bone | 5.4 ± 6.3 | 10.6 ± 3.5 | 9.3 ± 2.4 | 11.1 ± 5.6 | 2.6 ± 1.7 |

| Skin | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 6.9 ± 5.7 | 3.1 ± 1.6 | 7.0 ± 1.9 | 7.3 ± 2.1 |

In terms of background uptake, the two variants behaved very similarly. As is typical of antibody-based imaging agents, a decrease in the %ID/g in the blood occurred over the course of the experiment: to illustrate, with 89Zr-DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591, the amount of activity in the blood dropped from 11.1 ± 4.5 %ID/g at 24 h to 6.0 ± 1.6 %ID/g at 72 h to 2.9 ± 2.5 %ID/g at 96 h. The organs with the highest background uptake in both cases were the liver, spleen, and — not surprisingly given the osteophilic nature of the 89Zr4+ cation — bone. For example, with 89Zr-DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591, at 24 h, the amount of tracer uptake in the liver was 10.3 ± 6.6 %ID/g, the spleen 11.1 ± 3.0 %ID/g, and the bone 11.1 ± 6.6 %ID/g. However, by 96 h, the tumor to tissue activity ratios for each of these tissues were 21.8 ± 6.6, 33.6 ± 12.3, and 9.2 ± 1.3, respectively, with nearly identical results for 89Zr-DFO-NCS-J591. Experiments performed using 89Zr-labeled constructs with drastically reduced specific activities (created by co-injecting a 300-fold excess of the unlabeled J591 constructs) resulted in dramatically decreased tumor uptake values at 72 h post-injection, specifically a reduction from 56.3 ± 5.1 to 28.5 ± 6.8 %ID/g for 89Zr-DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591 and from 48.1 ± 9.3 to 23.5 ± 11.1 %ID/g for 89Zr-DFO-NCS-J591, indicating antigen-selective in vivo targeting in both cases. Importantly, these biodistribution data were also consistent with those obtained in the original report of non-site-specifically labeled J591 by Holland, et al.42

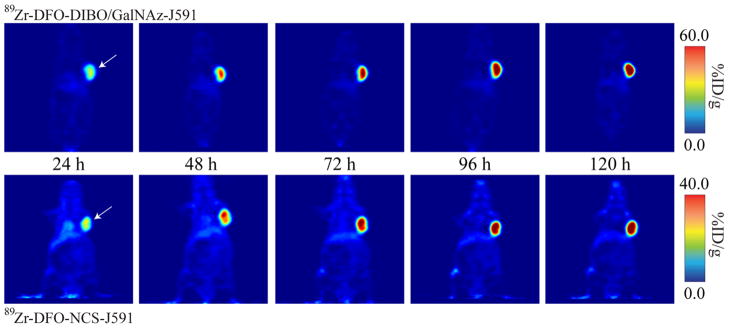

These biodistribution data were strongly reinforced by small animal PET imaging. In these experiments, nude mice bearing subcutaneous LNCaP xenografts were injected via tail vein with either 89Zr-DFO-NCS-J591 or 89Zr-DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591 (300–350 μCi, 100–150 μg) and imaged with static scans at 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h post-injection. The results (Figure 2) clearly indicate that the 89Zr-DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591 and 89Zr-DFO-NCS-J591 constructs are taken up significantly and selectively in the antigen-expressing LNCaP tumors. High blood pool activity and moderate background uptake in the heart, liver, and spleen are evident at early time points, but over the course of the experiment, this background activity is reduced and countered by a concomitant increase in signal in the tumor to a point at which it is by far the most prominent feature in the image.

Figure 2.

Coronal PET images of 89Zr-DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591 and 89Zr-DFO-NCS-J591 (11.1 – 12.9 MBq [300–345 μCi] injected via tail vein in 200 μL 0.9% sterile saline) in athymic nude mice bearing subcutaneous, PSMA-expressing LNCaP prostate cancer xenografts (white arrows) between 24 and 120 h post-injection.

Plainly, these data illustrate that this site-selective conjugation methodology creates a final radioimmunoconjugate that is nearly identical in its in vivo behavior to its non-site-selectively labeled cousin. Indeed, the small animal PET imaging results are actually qualitatively suggestive of an increase in absolute tumor uptake and tumor-to-background contrast for 89Zr-DFO-DIBO/GalNAz-J591 compared to 89Zr-DFO-NCS-J591 (see scale bars in Figure 2). However, the acute biodistribution data suggests that these differences are on the cusp of statistical signifiance, and thus further experimentation is required to elucidate their true statistical significance and, if they are in fact significant, determine the root cause.

Conclusion

In summary, we have developed a methodology for the site-selective radiolabeling of antibodies on the heavy chain N-linked glycans that is predicated on both enzyme-mediated reactions and strain-promoted catalyst-free click chemistry. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is one of a very few reports of an antibody modification methodology to target the heavy chain glycans as a site for selective radiolabeling and the only such strategy to avoid harsh sugar oxidation steps.7, 59 In the proof-of-concept system described here, the methodology was shown to be highly robust and reproducible and produced a 89Zr-labeled radioimmunoconjugate that is identical in terms of in vitro and in vivo to an analagous, non-site-selectively labeled construct. It is important to note that while this site-selective strategy did not result in large improvements in immunoreactivity or in vivo behavior in this case, we ascribe this to the well-developed and optimized nature of the antibody in our proof-of-concept system, J591. We are confident that this site-selective methodology will dramatically improve the in vitro and in vivo behavior of other, less robust antibody constructs by precluding the possibility of accidental conjugation at the antigen-binding site. In addition, this methodology may also prove useful with antibody fragments retaining N-linked glycosylation sites, whether natural or engineered. Although the reported workflow involves three 16 hour incubations, during the preparation of this manuscript we have been able to shorten the labeling process to two 16 hour incubations by instituting a one-pot deglycosylation/glycosylation step. Additionally, we have improved antibody yields by replacing the gel filtration steps with low protein-binding, single-use, centrifugal concentrators. Investigations applying this new methodology to various other antibodies and labels are currently underway and are proving successful at early stages. Ultimately, we believe that this strategy could play a critical role in the development of novel well-defined and highly selective radioimmunoconjugates for both the laboratory and the clinic.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Valerie Longo for aid with animal imaging experiments and Nicholas Ramos for aid in the purification of 89Zr. Services provided by the MSKCC Small-Animal Imaging Core Facility were supported in part by NIH grants R24 CA83084 and P30 CA08748. The authors also thank Drs. Pradman Qasba and Boopathy Ramakrishnan for their continued expert scientific input and support relating to the Gal-T(Y289L) enzyme expression, purification, and applications. The authors also thank the NIH (Award 1F32CA1440138-01, BMZ), the DOE (Award DE-SC0002184, JSL), the Mr. William H. Goodwin and Mrs. Alice Goodwin and the Commonwealth Foundation for Cancer Research, and the Experimental Therapeutics Center of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center for their generous funding.

Abbreviations

- PSMA

prostate specific membrane antigen

- DIBO

dibenzocyclooctyne

- UDP

uridine-5′-diphosphate

- GalNAz

N-azidozacetylgalactosamine

- DFO

desferrioxamine

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Additional methods, diagram of the regioisomers created by the copper-free click ligation, comprehensive DIBO-AF488 labeling efficiency data, and tables of tumor-to-tissue activity concentration ratios. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Wu AM. Antibodies and antimatter: The resurgence of immuno-PET. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:2–5. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.056887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zalutsky MR, Lewis JS. Radiolabeled antibodies for tumor imaging and therapy. Hand Radiopharm. 2003:685–714. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeglis BM, Lewis JS. A practical guide to the construction of radiometallated bioconjugates for positron emission tomography. Dalton Trans. 2011;40:6168–6195. doi: 10.1039/c0dt01595d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheng Z, De Jesus OP, Namavari M, De A, Levi J, Webster JM, Zhang R, Lee B, Syud FA, Gambhir SS. Small-animal PET imaging of human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2 expression with site-specific 18F-labeled protein scaffold molecules. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:804–813. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.047381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gill HS, Tinianow JN, Ogasawara A, Flores JE, Vanderbilt AN, Raab H, Scheer JM, Vandlen R, Williams SP, Mark J. A modular platform for the rapid site-specific radioalbeling of proteins with 18F exemplified by quantitative positron emission tomography of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2. J Med Chem. 2009;52:5816–5825. doi: 10.1021/jm900420c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hussain AF, Kampmeier F, von Felbert V, Merk HF, Tur MK, Barth S. SNAP-Tag technology mediates site-specific conjugation of antibody fragments with a photosensitizer and improves target specific phototoxicity in tumor cells. Biocon Chem. 2011;22:2487–2495. doi: 10.1021/bc200304k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeong JM, Lee J, Paik CH, Kim DK, Lee DS, Chung JK, Lee MC. Site-specific 99mTc-labeling of antibody using dihydraziniophthalazine (DHZ) conjugation to Fc region of heavy chain. Arch Pharm Res. 2004;27:961–967. doi: 10.1007/BF02975851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kampmeier F, Ribbert M, Nachreiner T, Dembski S, Beaufils F, Brecht A, Barth S. Site-specific, covalent labeling of recombinant antibody fragments via fusion to an engineered version of 6-O-alkylguanine DNA alkyltransferase. Biocon Chem. 2009;20:1010–1015. doi: 10.1021/bc9000257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li L, Crow D, Turatti F, Bading JR, Anderson AL, Poku E, Yazaki P, Carmichael J, Leong D, Wheatcroft MP, Raubitschek AA, Hudson PJ, Colcher D, Shivley JE. Site-specific conjugation of monodispersed DOTA-PEGn to a thiolated diabody reveals the effect of incrasing PEG size on kidney clearance and tumor uptake with improved 64-copper PET imaging. Biocon Chem. 2011;22:709–716. doi: 10.1021/bc100464e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tinianow JN, Gill HS, Ogasawara A, Flores JE, Vanderbilt AN, Luis E, Vandlen R, Darwish M, Junutula JR, Williams SP, Marik J. Site-specifically Zr-89-labeled monoclonal antibodies for ImmunoPET. Nucl Med Biol. 2010;37:289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raju TS, Briggs JB, Borge SM, Jones AJ. Species-specific variation in glycosylation of IgG: evidence for the species-specific sialylation and branch-specific galactosylation and importance for engineering recombinant glycoprotein therapeutics. Glycobiology. 2000;10:477–486. doi: 10.1093/glycob/10.5.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolfe CA, Hage DS. Studies on the rate and control of antibody oxidation by periodate. Anal Biochem. 1995;231:123–130. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clamp JR, Hough L. Some observations on the periodate oxidation of amino compounds. Biochem J. 1966;101:120–126. doi: 10.1042/bj1010120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramakrishnan B, Qasba PK. Structure-based design of beta 1,4-galactosyltransferase I (beta 4Gal-T1) with equally efficient N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase activity: point mutation broadens beta 4Gal-T1 donor specificity. J Biol Chem. 2002;7:20833–20839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111183200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark PM, Dweck JF, Mason DE, Hart CR, Buck SB, Peters EC, Agnew BJ, Hsieh-Wilson LC. Direct in-gel fluorescence detection and cellular imaging of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:11576–11577. doi: 10.1021/ja8030467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boeggeman E, Ramakrishnan B, Kilgore C, Khidekel N, Hsieh-Wilson LC, Simpson JT, Qasba PK. Direct identification of nonreducing GlcNAc residues on N-Glycans of glycoproteins using a novel chemoenzymatic method. Biocon Chem. 2007;18:806–814. doi: 10.1021/bc060341n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boeggeman E, Ramakrishnan B, Pasek M, Manzoni M, Puri A, Loomis KH, Waybright TJ, Qasba PK. Site specific conjugation of fluoroprobes to the remodeled Fc N-Glycans of monoclonal antibodies using mutant glycosyltransferases: Application for cell surface antigen detection. Biocon Chem. 2009;20:1228–1236. doi: 10.1021/bc900103p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khidekel N, Arndt S, Lamarre-Vincent N, Lippert A, Poulin-Kerstien KG, Ramakrishnan B, Qasba PK, Hsieh-Wilson LC. A chemoenzymatic approach toward the rapid and sensitive detection of O-GlcNAc posttranslational modifications. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:16162–16163. doi: 10.1021/ja038545r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramakrishnan B, Boeggeman E, Manzoni M, Zhu Z, Loomis K, Puri A, Dimitrov DS, Qasba PK. Multiple site-specific in vitro labeling of a single-chain antibody. Biocon Chem. 2009;20:1383–1389. doi: 10.1021/bc900149r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agard NJ, Bertozzi CR. Chemical approaches to perturb, profile, and perceive glycans. Acc Chem Res. 2009;42:788–797. doi: 10.1021/ar800267j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khidekel N, Ficarro SB, Clark PM, Bryan MC, Swaney DL, Rexach JE, Sun YE, Coon JJ, Peters EC, Hsieh-Wilson LC. Probing the dynamics of O-GlcNAc glycosylation in the brain using quantitative proteomics. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:339–348. doi: 10.1038/nchembio881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tai HC, Khidekel N, Ficarro SB, Peters EC, Hsieh-Wilson LC. Parallel identification of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins from cell lysates. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10500–10501. doi: 10.1021/ja047872b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qasba PK, Boeggeman E, Ramakrishnan B. Site-specific linking of biomolecules via glycan residues using glycosyltransferases. Biotech Prog. 2008;24:520–526. doi: 10.1021/bp0704034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramakrishnan B, Boeggeman E, Qasba PK. Novel method for in vitro O-glycosylation of proteins: Application for bioconjugation. Biocon Chem. 2007;18:1912–1918. doi: 10.1021/bc7002346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramakrishnan B, Boeggeman E, Manzoni M, Zhu Z, Loomis K, Puri A, Dimitrov DS, Qasba PK. Multiple site-specific in vitro labeling of single-chain antibody. Biocon Chem. 2009;20:1383–1389. doi: 10.1021/bc900149r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vocadlo D, Hang H, Kim E, Hanover J, Bertozzi CR. A chemical approach for identifying O-GlcNAc-modified proteins in cells. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9116–9121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1632821100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolb HC, Finn MG, Sharpless KB. Click chemistry: diverse chemical function from a few good reactions. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2001;40:2004–2021. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010601)40:11<2004::AID-ANIE2004>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wadas TJ, Wong EH, Weisman GR, Anderson CJ. Coordinating radiometals of copper, gallium, indium, yttrium, and zirconium for PET and SPECT imaging of disease. Chem Rev. 2010;110:2858–2902. doi: 10.1021/cr900325h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sletten EM, Bertozzi CR. Bioorthogonal chemistry: fishing for selectivity in a sea of functionality. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:6973–6998. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ning X, Guo J, Wolfert MA, Boons GJ. Visualizing metabolically labeled glycoconjugates of living cells by copper-free and fast huisgen cycloadditions. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2008;47:2253–2255. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laughlin ST, Baskin JM, Amacher SL, Bertozzi CR. In vivo imaging of membrane-associated glycans in developing zebrafish. Science. 2008;320:664–667. doi: 10.1126/science.1155106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laughlin ST, Bertozzi CR. Metabolic labeling of glycans with azido sugars and subsequent glycan-profiling and visualization via Staudinger ligation. Nat Prot. 2007;2:2930–2944. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zaro BW, Yang YY, Hang HC, Pratt MR. Chemical reporters for fluorescent detection and identification of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins reveal glycosylation of the ubiquitin ligase NEDD4-1. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:8146–8151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102458108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boeggeman E, Ramakrishnan B, Qasba PK. The N-terminal stem region of bovine and human beta1,4-galactosyltransferase I increases the in vitro folding efficiency of their catalytic domain from inclusion bodies. Prot Express Pur. 2003;30:219–229. doi: 10.1016/s1046-5928(03)00093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holland JP, Sheh YC, Lewis JS. Standardized methods for the production of high specific-activity zirconium-89. Nucl Med Biol. 2009;36:729–739. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hang HC, Yu C, Kato DL, Bertozzi CR. A metabolic labeling approach toward proteomic analysis of mucin-type O-linked glycosylation. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:14846–14851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2335201100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vosjan M, Perk LR, Visser GWM, Budde M, Jurek P, Kiefer GE, van Dongen G. Conjugation and radiolabeling of monoclonal antibodies with zirconium-89 for PET imaging using the bifunctional chelate p-isothiocyanatobenzyl-desferrioxamine. Nat Prot. 2010;5:739–743. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lindmo T, Boven E, Cuttitta F, Fedorko J, Bunn PA., Jr Determination of the immunoreactive fraction of radiolabeled monoclonal antibodies by linear extrapolation to binding at infinite antigen excess. J Immunol Meth. 1984;72:77–89. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(84)90435-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindmo T, Bunn PA., Jr Determination of the true immunoreactive fraction of monoclonal antibodies after radiolabeling. Meth Enzym. 1986;121:678–91. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)21067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anderson CJ, Connett JM, Schwarz SW, Rocque PA, Guo LW, Philpott GW, Zinn KR, Meares CF, Welch MJ. Copper-64-labeled antibodies for PET imaging. J Nucl Med. 1992;33:1685–1691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holland JP, Caldas-Lopes E, Divilov V, Longo VA, Taldone T, Zatorska D, Chiosis G, Lewis JS. Measuring the pharmacodynamic effects of a novel Hsp90 inhibitor on HER2/neu expression in mice using Zr-89-DFO-trastuzumab. Plos One. 2010:5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holland JP, Divilov V, Bander NH, Smith-Jones PM, Larson SM, Lewis JS. Zr-89-DFO-J591 for ImmunoPET of prostate-specific membrane antigen expression in vivo. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:1293–1300. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.076174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vugts DJ, Van Dongen G. 89Zr-labeled compounds for PET imaging guided personalized therapy. Drug Disc Today. 2011;8:e53–e61. doi: 10.1016/j.ddtec.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu H, Moy P, Kim S, Xia Y, Rajasekaran A, Navarro V, Knudsen B, Bander NH. Monoclonal antibodies to the extracellular domain of prostate-specific membrane antigen also react with tumor vascular endothelium. Cancer Res. 1997;57:3629–3634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu H, Rajasekaran AK, Moy P, Xia Y, Kim S, Navarro V, Rahmati R, Bander NH. Constitutive and antibody-induced internalization of prostate-specific membrane antigen. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4055–4060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olson WC, Heston WDW, Rajasekaran AK. Clinical trials of cancer therapies targeting prostate-specific membrane antigen. Revi Rec Clin Trials. 2007;2:182–90. doi: 10.2174/157488707781662724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manyak MJ. Indium-111 capromab pendetide in the management of recurrent prostate cancer. Exp Rev Anticancer Ther. 2008;8:175–181. doi: 10.1586/14737140.8.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Apolo AB, Pandit-Taskar N, Morris MJ. Novel tracers and their development for the imaging of metastatic prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:2031–2041. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.050658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cho SY, Gage KL, Mease RC, Senthamizhchelvan S, Holt DP, Jeffrey-Kwanisai A, Endres CJ, Dannals RF, Sgouros G, Lodge M, Eisenberger MA, Rodriguez R, Carducci MA, Rojas C, Slusher BS, Kozikowski AP, Pomper MG. Biodistribution, tumor detection, and radiation dosimetry of F-18-DCFBC, a low-molecular-weight inhibitor of prostate-specific membrane antigen, in patients with metastatic prostate cancer. J Nucl Med. 53:1883–1891. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.104661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McDevitt MR, Barendswaard E, Ma D, Lai L, Curcio MJ, Sgouros G, Ballangrud AM, Yang WH, Finn RD, Pellegrini V, Geerlings MW, Lee M, Brechbiel MW, Bander NH, Cordon-Cardo C, Scheinberg DA. An alpha-particle emitting antibody ([Bi-213]J591) for radioimmunotherapy of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6095–6100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vallabhajosula S, Smith-Jones PM, Navarro V, Goldsmith SJ, Bander NH. Radioimmunotherapy of prostate cancer in human xenografts using monoclonal antibodies specific to prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA): Studies in nude mice. Prostate. 2004;58:145–155. doi: 10.1002/pros.10281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vallabhajosula S, Kuji I, Hamacher KA, Konishi S, Kostakoglu L, Kothari PA, Milowski MI, Nanus DM, Bander NH, Goldsmith SJ. Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of In-111-Lu-177-labeled J591 antibody specific for prostate-specific membrane antigen: Prediction of Y-90-J591 radiation dosimetry based on In-111 or Lu-177? J Nucl Med. 2005;46:634–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vallabhajosula S, Goldsmith SJ, Kostakoglu L, Milowsky MI, Nanus DM, Bander NH. Radioimmunotherapy of prostate cancer using Y-90- and Lu-177-labeled J591 monoclonal antibodies: Effect of multiple treatments on myelotoxicity. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:7195S–7200S. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-1004-0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pandit-Taskar N, O’Donoghue JA, Morris MJ, Wills EA, Schwartz LH, Gonen M, Scher HI, Larson SM, Divgi CR. Antibody mass escalation study in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer using (111)In-J591: Lesion detectability and dosimetric projections for (90)Y Radioimmunotherapy. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:1066–1074. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.049502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McDevitt MR, Ma DS, Lai LT, Simon J, Borchardt P, Frank RK, Wu K, Pellegrini V, Curcio MJ, Miederer M, Bander NH, Scheinberg DA. Tumor therapy with targeted atomic nanogenerators. Science. 2001;294:1537–1540. doi: 10.1126/science.1064126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Deri MA, Zeglis BM, Francesconi LC, Lewis JS. PET imaging with Zr-89: From radiochemistry to the clinic. Nucl Med Biol. 40:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Warnock D, Bai X, Autote K, Gonzales J, Kinealy K, Yan B, Qian J, Stevenson T, Zopf D, Bayer RJ. In vitro galactosylation of human IgG at 1 kg scale using recombinant galactosyltransferase. Biotech Bioeng. 2005;92:831–842. doi: 10.1002/bit.20658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hossler P, Khattak SF, Li ZJ. Optimal and consistent protein glycosylation in mammalian cell culture. Glycobiology. 2009;19:936–949. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwp079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alvarez VL, Wen ML, Lee C, Lopes D, Rodwell JD, McKearn TJ. Site-specifically modified 111In labelled antibodies give low liver backgrounds and improved radioimmunoscintigraphy. Nucl Med Biol. 1986;13:347–352. doi: 10.1016/0883-2897(86)90008-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.