Abstract

Purpose

Activation of nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB) has been implicated in chronic inflammatory disorders and is a key regulator of genes involved in response to infection, inflammation and stress. Interstitial cystitis and painful bladder syndrome are common inflammatory disorders of the urinary bladder characterized by frequent urination and bladder pain. The role of NF-κB activation in bladder inflammation has not been well defined.

Material and Methods

Female transgenic NF-κB-Luciferase (Luc) Tag mice were used to perform serial, noninvasive in vivo and ex vivo molecular imaging of NF-κB activation in the whole body after administration of arsenic trioxide (5mg/kg), lipopolysaccharide (2mg/kg), or cyclophosphamide (200mg/kg) to initiate acute transient inflammation in the bladder. Pretreatment with dexamethasone (10mg/kg) was used to modulate the cyclophosphamide-induced NF-κB-dependent luminescence in vivo.

Results

Treatment of NF-κB-Luc mice with chemicals increased luminescence in a time- and organ- specific manner both in vivo and ex vivo. The highest levels of bladder NF-κB-dependent luminescence were observed 4 h after cyclophosphamide administration. Pretreatment with dexamethasone 1 h before injection of cyclophosphamide significantly down-regulated cyclophosphamide-induce bladder NF-κB-dependent luminescence, ameliorated the grossly evident pathologic features of acute inflammation, and diminished cellular immunostaining for NF-κB in the bladder.

Conclusions

NF-κB activity may play an important role in the patho-physiology of bladder inflammation and NF-κB-Luc mice can serve as a useful model for screening potential candidate drugs for treatment of cystitis associated with aberrant NF-κB activity. Such screening may significantly aid the development of therapeutic strategies to manage inflammatory disorders in the urinary bladder.

Keywords: urinary bladder, cystitis, NF-kappaB, molecular imaging, inflammation

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory disease of the urinary bladder such as interstitial cystitis and painful bladder syndrome are common in the United States, and currently are associated with annual healthcare expenditures estimated at $750 million dollars.1 The disease presents with varying complex symptoms, including urinary frequency, nocturia, urinary urgency, pain on bladder filling, suprapubic pain and dyspareunia, which are frequently accompanied by anxiety and depression.2 Evidence suggests that there may be multiple causes of the interstitial cystitis syndrome complex, the underlying mechanisms are still elusive, and are thought to be linked to inflammatory responses to infection, stress or exposure to chemicals that mediate the clinical symptoms.3

Several lines of evidence suggest that the transcription factor, nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB) is associated with various pathological conditions including toxic/septic shock, graft versus host disease, acute inflammatory conditions, acute phase response, and cancer.4 NF-κB complexes as a heterotrimer essentially composed of p50 and RelA/p65 subunits normally sequestered in the cytoplasm bound to an inhibitory protein, IκB. With the onset of NF-κB activation, the IκB proteins become phosphorylated, ubiquitinated, and eventually degraded. This liberates NF-κB, allowing its translocation to the nucleus, where it enhances the transcription of specific genes regulating inflammatory responses. NF-κB upregulation is accompanied by the enhanced recruitment of inflammatory cells and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines at the site of inflammation.5 Activation of NF-κB/p65 and its nuclear localization has been demonstrated in bladder biopsies from patients with interstitial cystitis,6 however, its role in bladder inflammation has not been well defined.

In this study, we sought to evaluate NF-κB activation in the bladder in direct response to exposure of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), inorganic arsenic trioxide (As2O3) and cyclophosphamide (CYP), which triggers inflammatory response in the bladder that mimics some of the basic features of interstitial cystitis. We used a transgenic mouse with a luciferase reporter under the control of a NF-κB promoter to monitor NF-κB activity and associated inflammation in mouse urinary bladder after administration of these chemicals into the systemic circulation of living transgenic NF-κB-Luciferase mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Transgenic NF-κB-Luciferase Tag female mice (Jackson Labs, Bar Harbor, Maine) originating from a C57BL/6JxCBA/J background and tagged with three identical NF-κB sites (5′GGGACTTTCC3′) derived from the Igκ-light-chain enhancer region, coupled to the luciferase reporter gene, were used in the study to demonstrate the role of NF-κB in vesical inflammation.

Chemicals

The following chemicals were used to induce NF-κB activity in mice 24–26 weeks of age with body weights of 30–32 g: i) 30 μL i.v. injections in the tail vein with LPS (2 mg/kg); ii) 100 μL i.p. As2O3 (5 mg/kg), and iii) 100 μL i.p. CYP (200 mg/kg) (all from Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Some mice were injected i.p. with dexamethasone (DEXO) (10 mg/kg) (Sigma) 1 h before CYP administration. All animal experiments were performed according to institutional guidelines for animal care.

Luciferase activity

Luciferase activity in vivo and ex vivo in transgenic mice was assessed as previously described with some modifications.7 Briefly, imaging of transgenic mice was performed with an ultra-sensitive camera consisting of an image intensifier coupled to a CCD camera of IVIS 150 System Xenogen (Alameda, CA). Before imaging, mice were either treated with depilatory cream on the ventral side (Veet) of the skin and abdominal muscles were removed to expose internal organs. D-Luciferin (75 mg/kg; Xenogen) dissolved in PBS, was injected i.p. into mice which were pre-anesthetized by isoflurane at a concentration of 2% with 98% oxygen. The pseudo colored images represent light intensity (white is the strongest and blue is the weakest). Individual organs to be imaged were excised from the mice 5 min following i.v. injection of D-luciferin. Organs were then placed in a culture dish and immediately imaged as described. All images were processed and standardized with the software Living Image 2.5 (Igor Pro WaveMetrics, Inc., Alameda, CA). Whole body and incised organ images were obtained 2 and 4 h after chemical injections and/or 5 h after dexamethasone pretreatment.

Immunohistochemistry

The expression of NF-κB in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded whole mount mouse urinary bladder was evaluated using the goat polyclonal IgG (200 μg/mL); and ABC Staining System (both from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc, Santa Cruz, CA). Briefly, 4-μm thick urinary bladder sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, immersed in target Reveal™ solution (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA), and underwent heating antigen retrieval in a pressure cooker chamber. The sections were blocked with PEROXIdazed-1 for endogenous peroxidase activity and BACKGROUNDsniper (both from Biocare Medical) to reduce nonspecific background staining, and incubated in primary monoclonal antibodies for 1 h at RT. Control sections were incubated with isotype-matched IgG normal goat serum. After washing three times in TBS, sections were incubated for 30 min at RT with biotinylated secondary antibody followed by detection of immunoreactive complexes (ABC Staining System). Slides were then counterstained in hematoxylin mounted in crystal mount media, and dried overnight.

Urinary bladder histology

Routine H&E-stained histological sections of urinary bladder were evaluated for the presence of CYP-induced toxicity and inflammatory responses. Histological findings were correlated with NF-κB activation.

Statistical analysis

Differences between groups were evaluated using the ANOVA test. Differences were considered to be statistically significant at P<0.05.

RESULTS

Levels of chemical-induced NF-κB activity in vivo

To monitor chemical-induced NF-κB activity, D-Luciferin was injected i.p., and the mice were placed on their backs in a light-sealed chamber and imaged as described.7 Following administration of As2O3, LPS, and CYP, image monitoring over several hours showed significantly increased NF-κB-dependent luminescence in LPS and CYP treated mice (Fig. 1A). In contrast with As2O3, 2 h after inoculation of chemicals the whole body luminescence was increased approximately 2-fold in LPS treated mice and remained at these levels over the next 4 h. CYP administration increased the NF-κB-dependent luminescence in vivo up to 2 times at 2 h time point and 3–3.5 times at 4 h after the CYP treatment (Fig. 1A and B).

FIGURE 1.

Whole body in vivo imaging of NF-κB-Luc mice. (A) Animals received i.v. injection in the tail vein with lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 2 mg/kg), and i.p. injection with arsenic trioxide (As2O3, 5 mg/kg), and cyclophosphamide (CYP, 200 mg/kg); equivalent volume of phosphate-buffered saline, to serve as control. Images are presented after color scale adjustment. Gray scale images were obtained before luminescence imaging for reference. (B) Statistical analysis of total photon flux presented in time-fashion manner. White bars – controls (PBS); grey bars – As2O3; striped bars – LPS; black bars – CYP. The SD is indicated. * - p<0.05; ** - p<0.01 compared with controls. Details are described in ‘materials and methods’ section.

Levels of chemical-induced NF-κB activity ex vivo

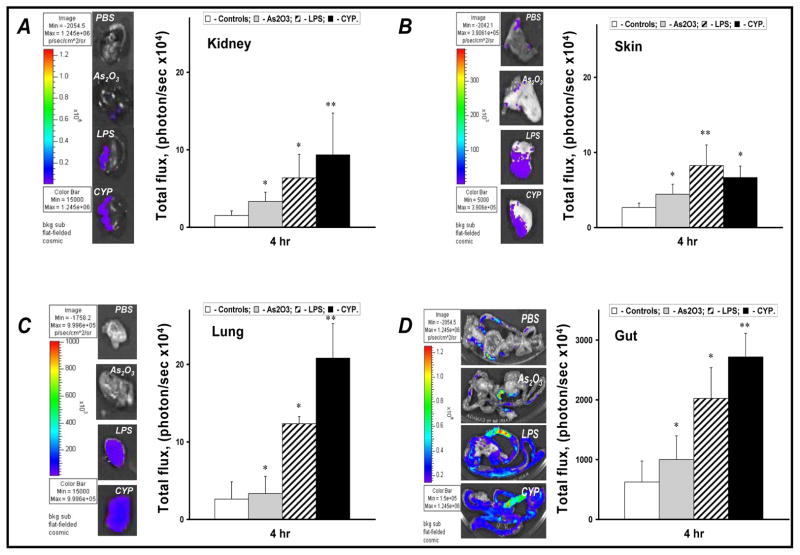

To determine the effects of As2O3, LPS, and CYP on F-κB-dependent luminescent activity in various mouse tissues, the chemical-induced NF-κB-dependent luminescence was assessed in kidney, skin, lungs, and gut. Figure 2A exhibit ex vivo luminescence after administration of chemicals which markedly increased in these organs. LPS treatment provided the strongest stimuli for NF-κB activity in mouse skin. However, single dose of CYP was able to induce a much stronger flux of NF-κB-dependent luminescence from other organs studied and exceeded the levels of the spontaneous luminescence from gut to 4 fold, from kidney to 6 fold, and from lung to 8 fold, respectively. (Fig. 2A and B)

FIGURE 2.

Ex-vivo NF-κB-dependent luminescence activity assessment of mouse kidney (A), skin (B), lung (C), and gut (D) after chemical administration. The images were taken 4 h after chemical administration and presented after color scale adjustment. Data represent the mean value of total photon flux from tissue studied after chemical administration. White bars – controls (PBS); grey bars – As2O3; strip bars – LPS; black bars – CYP. The SD is indicated.* - p<0.05; ** - p<0.01 compared with controls. Details are described in ‘materials and methods’ section.

Levels of chemical-induced NF-κB activity in bladder tissue

To further evaluate the effects of chemicals on NF-κB activity, the bladders from various treated groups were excised and imaged. Figure 3A indicates quantitatively that CYP was consistently the strongest inducer of NF-κB activity in the bladder tissue. Indeed, levels of NF-κB activity in bladders were significantly elevated 4 h after single dose of As2O3 (1.8-fold), LPS (1.9-fold), and CYP (2.3-fold) (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Ex-vivo NF-κB-dependent luminescence activity assessment of mouse urinary bladder after chemical administration. The bladder images were taken 4 h after chemical administration and presented after color scale adjustment. (B) Statistical analysis of total photon flux is presented in time-fashion manner. Data represent the mean value of total photon flux from bladder after chemical administration. White bars – controls (PBS); grey bars – As2O3; strip bars – LPS; black bars – CYP. The SD is indicated. * - p<0.05; ** - p<0.01 compared with controls. Details are described in ‘materials and methods’ section.

Next we evaluated the effects of the most potent chemical agent – CYP in modulating NF-κB activity in transgenic mice by the in vivo and ex vivo techniques. CYP-induced transgenic mice were pretreated with dexamethasone (10 mg/kg), a well-known suppressor of NF-κB activity.8 As demonstrated in Figure 4A, imaging of living mice revealed that 10 mg dexamethasone/kg markedly reduced the CYP-induced NF-κB-dependent luminescence in vivo after single CYP administration. To further evaluate dexamethasone modulation of NF-κB activity in bladder tissue of transgenic mice, bladders were excised (Fig. 4D) after a single CYP injection, images were taken and analyzed (Fig. 4B, C). The results demonstrate that CYP-induced NF-κB-dependent luminescence was reduced to 1.5- to 2-fold from bladders excised after dexamethasone pretreatment. Such results reinforced our predictions since bladders in dexamethasone pretreated mice showed lower levels of hyperemia as a major gross anatomy sign of CYP-induced hemorrhagic cystitis (Fig. 4D).

FIGURE 4.

Effect of dexamethasone on ex-vivo NF-κB-dependent luminescence activity of mouse urinary bladder after cyclophosphamide (CYP) administration. Mice were i.p. injected with dexomethasone (DEXO, 10 mg/kg), and CYP (200 mg/kg) was administered 1 h later to these animals and imaged after 4 h of treatment. (A) Whole body in vivo imaging, and (B) ex vivo bladder luminescence assessment. (C) Statistical analysis represents the mean value of total photon flux from the bladders. (D) Pre-treatment with dexamethasone ameliorates hyperemia which is a gross anatomic symptom of CYP-induced hemorrhagic cystitis. SD as indicated. White bars – controls (PBS); black bar – CYP, black and white bar – DEXO+CYP. * - p<0.05 compared with controls and DEXO+CYP. Details are described in ‘materials and methods’ section.

Cyclophosphamide regulates activity of nuclear and cytosolic NF-κB/p65 in mouse bladder

Severe bladder damage, including epithelial loss, severe interstitial edema, and inflammatory cell infiltration in the lamina propria, and stroma was observed 4 h after CYP administration (Fig. 5A, H/E staining). In order to determine whether systemic CYP administration has a direct impact on NF-κB activity the bladders of CYP-treated mice were subjected to immunostaining for NF-κB/p65 to evaluate its localization in bladder tissue. Figure 5A demonstrate that basic intra-bladder levels of NF-κB/p65 (control) were consistent with a non-functionally active cytosolic fraction. The levels NF-κB/p65 were markedly increased after CYP administration. The strongest nuclear expression of functionally active NF-κB/p65 was observed in the bladder micro-vessel endothelial cells, histiocytes, blood, and extravasated leukocytes after CYP administration. Both active extravasation and stromal accumulation of leukocytes with high levels of nuclear NF-κB/p65 activity were frequently observed in bladders of CYP-treated mice (Fig. 5A, NF-κB/p65 staining).

FIGURE 5.

Assessment of NF-κB activity in the urinary bladder tissue 4 h after i.p. administration of a single dose (200 mg/kg) of cyclophosphamide (CYP). One hour before CYP administration some animals were i.p. injected with dexamethasone (DEXO) (10 mg/kg). (A) H&E histology and immunostaining of the bladder for NF-κB/p65 in representative samples from NF-κB/Luc transgenic mice. CYP induced significant tissue damage as evident by severe edema (black asterisks), leukocyte infiltration, and extensive epithelial loss (open arrowheads). Pre-treatment with DEXO reduced epithelial loss (black arrowheads) and edemas (black asterisk) in CYP injected animals. The strongest nuclear expression of NF-κB (dark brown color) was observed in microvessel endothelium (green arrows), extravasating leukocytes (red arrows), stromal scattered leucocytes (black arrows), and in the stromal accumulated leukocytes (inside black circle) after CYP administration. The staining was significantly diminished by dexamethasone (DEXO). Red dotted circles indicate microvessels. Left column presents bladder H&E staining. Right column depicts staining for NF-κB located inside of the black squares of the right column. (B) Box-plot analysis of absolute number of bladder cells positively stained only for NF-κB in the nuclei in the formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded whole mount mouse bladder specimens from animal treated with CYP. Results are expressed as absolute numbers of nuclear NF-κB positive cells in whole mouse bladder. The average is shown as a horizontal line through the box. The lower and upper margins of the box represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, with the extended arms representing the minimal and maximal number, respectively. The data were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with 95% confidence limits and Tukey’s correction. Details are described in ‘materials and methods’ section.

Furthermore, pretreatment with dexamethasone attenuated the histological signs of tissue edema, epithelium shredding (Fig. 5H/E staining), as well as significantly reduced the activity of CYP-induced NF-κB/p65 both in micro-vessel endothelium and blood-originated leukocytes (Fig. 5, NF-κB/p65 staining). Indeed, neither NF-κB active blood cell extravasation nor stromal accumulation of NF-κB active leukocytes was detected in the bladders of DEXO-pretreated mice. The quantification of NF-κB positive cells after various treatments and controls are shown in figure 6.

FIGURE 6.

DISCUSSION

In this study we assessed the involvement of NF-κB during inflammatory response in the urinary bladder upon exposure to various chemicals and toxins known to cause bladder inflammation in humans. NF-κB is highly activated at lesional sites in a wide range of human chronic inflammatory diseases including cancers. The relationship between circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines and post-transition effects of NF-κB in urogenital organs has been reported,7 indicating a direct link between NF-κB activity and tissue inflammation.9 Kiuchi et al. suggested that NF-κB itself might be a rational target for therapeutic intervention in cases of acute hemorrhagic cystitis.10 However, nuclear localization or DNA binding alone cannot distinguish between transcriptionally active and inactive NF-κB.11 The advantage of using transgenic mice to make this distinction is that they express a luciferase reporter whose transcription is dependent upon active nuclear localization of NF-κB. Previously, we have reported direct evidence that IL-1β causes NF-κB activation in the mouse prostate in vivo and ex vivo, resulting in leukocyte traffic from microvessels into the stroma, followed by the stromal accumulation of mononuclear cells using transgenic NF-κB-luciferase tag mice.7 We have also shown that IL-1β administration induces NF-κB-responsive genes to promote aberrant NF-κB/p65 activity, which may be critical in the development of acute inflammation in the prostate through its role in the production of chemoattractant signals that promote homing, extravasation and stromal accumulation of inflammatory cells.9 Here we demonstrate a NF-κB transactivation in the bladder after exposure to chemicals, suggesting that NF-κB may play an important role in bladder inflammation.

Studies have shown that arsenic compounds in the drinking water or diet induces cytotoxicity and necrosis of the urothelial superficial layer and hyperplasia in vivo.12 The mode of action of inorganic arsenic in rodents appears to involve urothelial cytotoxicity, increased cell proliferation and ultimately tumor development. Cytotoxicity is attributed to the generation of reactive trivalent arsenicals excreted in the urine.13 In this study, we observed significant upregulation of NF-κB-dependent luminescence in the bladder, and minimal activation of NF-κB-dependent luminescence in vivo in the kidneys, skin, lungs, or gut after As2O3 administration. This may be due to active elimination of As2O3 by the kidneys and more intensive exposure of the bladder urothelium to its metabolites. Furthermore, increased rates of chromosome aberrations and micronuclei formation were observed in human exfoliated bladder cells exposed to relatively long periods to inorganic As2O3. However, the precise mechanisms of bladder carcinogenesis are still not well defined.14

The gram-negative bacterium E. coli is the leading cause of urinary tract infection.15 Recognition of LPS, a component of the outer membrane of E. coli, by urothelium requires an array of proteins. LPS-binding protein and soluble CD14 are present in the serum and facilitate the transfer of LPS to membrane-anchored CD14, which is a strong factor in IL-8 induction in bladder urothelial response to LPS.16 Normal human urothelium contains inactive NF-κB complexes. Treatment of urothelial cells in vitro with LPS induces activation of the NF-κB signal transduction machinery, degradation of its inhibitor, IκBα and translocation of this primary factor into the nucleus to induce pro-inflammatory IL-8 expression.17 Following LPS instillation, the NF-κ/p65 rapidly becomes localized in the bladder cell nucleus, peaking at 30 to 60 min, returning to control level by 24 h.6 In our study, LPS was the most powerful inducer of NF-κB-dependent luminescence in vivo at 2 h time point. The in vivo and ex vivo data corroborates with the earlier findings and provide evidence that exposure of LPS may contribute to direct NF-κB activation in the bladder.

Bladder damage in response to CYP exposure is induced by the direct contact of acrolein, a metabolite of CYP, with urothelium, followed by intense inflammatory events.18 This study demonstrates a marked bladder damage characterized by mucosal erosion and ulcerations, leukocyte infiltration, edema and hemorrhage peaked at 4 h of CYP exposure. High concentrations of the NF-κB dependent molecules such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and COX-2 provide indirect evidence of a role of NF-κB in initiating and perpetuating CYP-induced inflammatory process.19, 20 Our study revealed that CYP is the most powerful inducer of NF-κB-dependent luminescence in vivo at the 4 h time point as compared with other chemicals and documents that CYP is the strongest inducer of NF-κB-dependent luminescence in various other internal organs. To further investigate the role of NF-κB in generating CYP-mediated bladder toxicity, the flux of CYP-induced NF-κB-dependent luminescence in the bladder was assessed after pre-treatment with dexamethasone, a well known NF-κB inhibitor. Both visual reduction of bladder hyperemia and significant down-regulation of NF-κB activity in vivo and in the bladder ex vivo in mice pre-treated with dexamethasone provide direct evidence of the involvement of NF-κB signaling in CYP-induced bladder inflammation.

The participation of cellular components in the up-regulation of CYP-induced NF-κB-dependent luminescence ex vivo, and the expression of NF-κB/p65 in bladder tissue was further evaluated. It has been observed that biopsies in patients with interstitial cystitis exhibit nuclear NF-κB activation predominantly in bladder urothelial cells and cells in the lamina propria.21 This study illustrates that bladders of control mice had diffuse NF-κB/p65 cellular distribution, predominantly in the cytoplasm. We observed active nuclear NF-κB/p65 expression in bladders with acute CYP-induced inflammation, which was ameliorated by pre-treatment with dexamethasone. Additionally, the acute damage-related changes induced by CYP, administered at varying doses, showed varying patterns, possibly correlating with variations in NF-κB/p65 expression. The number of cells with intensive nuclear NF-κB/p65 activity in damaged bladder stroma was 2.5–3.0 folds higher than in dexamethasone pre-treated or control mice. Overall, the changes may be summarized as rapid and intense with NF-κB expression in the endothelium of microvessels; leakage of NF-κB-expressing blood-derived cells from microvessels into the stroma; and accumulation of NF-κB-expressing mononuclear- and polymorphonuclear-like cells in the stroma.

CONCLUSION

In the current study, we present findings supporting the critical role of NF-κB in the pathogenesis of chemically-induced bladder inflammation as a model that mimics experimental cystitis. Further investigation of the role of NF-κB activity in inducing bladder inflammation, using molecular imaging, appears to be warranted. Our results illustrate that treatment with dexamethasone, a known NF-κB inhibitor, significantly reduced CYP-induced NF-κB-dependent luminescence and NF-κB/p65-expressing cell burden in the bladders of transgenic mice. Therefore, these animals may be useful for screening drugs that are considered potentially valuable in the management of inflammatory conditions and/or certain urologic malignancies that are associated with aberrant NF-κB activity.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by grants from United States Public Health Services NCI, RO1CA108512, NIDDK P20DK090871 and the Sullivan Foundation for the study of prostatitis.

References

- 1.Payne CK, Joyce GF, Wise M, et al. Interstitial cystitis and painful bladder syndrome. J Urol. 2007;177:2042. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naliboff BD, Rhudy J. Anxiety in functional pain disorders. In: Mayer EA, editor. Functional Pain Syndromes: Presentation and Pathophysiology. Seattle: International Association for the Study of Pain; 2009. pp. 185–214. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saini R, Gonzalez RR, Te AE. Chronic pelvic pain syndrome and the overactive bladder: the inflammatory link. Curr Urol Rep. 2008;9:314. doi: 10.1007/s11934-008-0054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Courtois G, Gilmore TD. Mutations in the NF-kappaB signaling pathway: implications for human disease. Oncogene. 2006;25:6831. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawrence T. The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a001651. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang XC, Saban R, Kaysen JH, et al. Nuclear factor kappa B mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in the urinary bladder. J Urol. 2000;163:993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vykhovanets EV, Shukla S, MacLennan GT, et al. Molecular imaging of NF-kappaB in prostate tissue after systemic administration of IL-1 beta. Prostate. 2008;68:34. doi: 10.1002/pros.20666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahman I. Regulation of nuclear factor-kappa B, activator protein-1, and glutathione levels by tumor necrosis factor-α and dexamethasone in alveolar epithelial cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60:1041. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00392-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vykhovanets EV, Shukla S, MacLennan GT, et al. IL-1 beta-induced post-transition effect of NF-kappaB provides time-dependent wave of signals for initial phase of intrapostatic inflammation. Prostate. 2009;69:633. doi: 10.1002/pros.20916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiuchi H, Takao T, Yamamoto K, et al. Sesquiterpene lactone parthenolide ameliorates bladder inflammation and bladder overactivity in cyclophosphamide induced rat cystitis model by inhibiting nuclear factor-kappaB phosphorylation. J Urol. 2009;181:2339. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sizemore N, Leung S, Stark GR, et al. Activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in response to interleukin-1 leads to phosphorylation and activation of the NF-kappaB p65/RelA subunit. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4798. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.4798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki S, Arnold LL, Pennington KL, et al. Dietary administration of sodium arsenite to rats: relations between dose and urinary concentrations of methylated and thio-metabolites and effects on the rat urinary bladder epithelium. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2010;244:99. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suzuki S, Arnold LL, Ohnishi T, et al. Effects of inorganic arsenic on the rat and mouse urinary bladder. Toxicol Sci. 2008;106:350. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warner ML, Moore LE, Smith MT, et al. Increased micronuclei in exfoliated bladder cells of individuals who chronically ingest arsenic contaminated water in Nevada. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1994;3:583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ronald A. The etiology of urinary tract infection: traditional and emerging pathogens. Am J Med. 2002;113 (Suppl 1A):14S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimizu T, Yokota S, Takahashi S, et al. Membrane-anchored CD14 is important for induction of interleukin-8 by lipopolysaccharide and peptidoglycan in uroepithelial cells. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2004;11:969. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.11.5.969-976.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rackley RR, Bandyopadhyay SK, Fazeli-Matin S, et al. Immunoregulatory potential of urothelium: characterization of NF-kappaB signal transduction. J Urol. 1999;162:1812. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)68243-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klinger MB, Dattilio A, Vizzard MA. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in urinary bladder in rats with cyclophosphamide-induced cystitis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R677. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00305.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ribeiro RA, Freitas HC, Campos MC, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1beta mediate the production of nitric oxide involved in the pathogenesis of ifosfamide induced hemorrhagic cystitis in mice. J Urol. 2002;167:2229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martinez-Ferrer M, Iturregui JM, Uwamariya C, et al. Role of nicotinic and estrogen signaling during experimental acute and chronic bladder inflammation. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:59. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdel-Mageed AB, Ghoniem GM. Potential role of rel/nuclear factor-kappaB in the pathogenesis of interstitial cystitis. J Urol. 1998;160:2000. doi: 10.1097/00005392-199812010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]