Abstract

Metal ion probes are used to assess the accessibility of cysteine side chains in polypeptides lining the conductive pathways of ion channels and thereby determine the conformations of channel states. Despite the widespread use of this approach, the chemistry of metal ion-thiol interactions has not been fully elucidated. Here, we investigate the modification of cysteine residues within a protein pore by the commonly used Ag+ and Cd2+ probes at the single-molecule level, and provide rates and stoichiometries that will be useful for the design and interpretation of accessibility experiments.

Introduction

Ion channels play key roles in the electrical excitability of cells and in synaptic transmission, enabling physiological activities as diverse as memory storage and muscle contraction. Crucially, ion channels regulate the selective passive flow of permeant ions through membranes by transitions between closed and open conformational states. The dynamics of these transitions can be studied in detail with the use of electrophysiological techniques. However, additional information is required to understand the molecular bases of the underlying protein conformational changes, and in this regard the substituted-cysteine accessibility method (SCAM) (1) combined with x-ray crystallography (2) has been highly informative.

Two types of thiol-specific reagents are commonly used as probes in SCAM, namely, thiophilic metal ions (e.g., Ag+ (3), Cd2+ (4), Zn2+ (5), and Hg2+ (6)) and electrophilic reagents (e.g., methanethiosulfonates (7)). The thiophilic metal ions have sizes (8) and water exchange rates (9) similar to those of natural permeant ions, and therefore are expected to pass through the channel or be prevented from doing so in accord with the channel state (open, closed, desensitized, etc.). Hence, the accessibility of cysteine residues introduced by, e.g., scanning mutagenesis, reveals information about the structures of conformational states. The ability of these metal ions to form multiply coordinated complexes has also been used to reveal the spatial proximity of amino acid residues located on different subunits of ion channels (10).

Here, we use the staphylococcal α-hemolysin (αHL) transmembrane pore (11) as a nanoreactor (12) to examine metal ion-thiol chemistry at the single-molecule level. Reaction sites can be engineered into the lumen of the αHL pore and have been used to examine a variety of chemical interactions (12), including the interactions of divalent metal ions with histidine side chains (13) and EDTA-like chelators (14). In this work, we used a cysteine-containing αHL pore (PC) to study the kinetics and stoichiometry of two commonly used metal ion probes (Ag+ and Cd2+) with a thiol group. We also examined the effects of neighboring cysteine and histidine side chains.

Materials and Methods

Mutagenesis at multiple widely separated sites

The αHL AG gene encodes a polypeptide with four mutations (Lys-8→Ala, Met-113→Gly, Lys-131→Gly, and Lys-147→Gly) and was constructed from the template pT7-WT-αHL (15). Another gene, G137C-AG, encodes an αHL polypeptide containing the same four mutations, with an additional Gly-137→Cys mutation and an extension of eight-aspartate residues at the C-terminus, and was constructed from the template pT7-G137C-D8-RL3 (16). RL3 is a version of the WT αHL gene with silent mutations in the segment of the gene that encodes the region around and within the stem domain. These mutations produce six new restriction sites (17). Both αHL AG and αHL G137C-AG (C) were constructed by means of multiple site-directed mutagenesis (QuikChange Lightning Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit, catalog no. 210515; Agilent Technologies, Berkshire, UK). For the AG gene, a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was carried out with the following four sense primers: K8A, 5′-GCAGATTCTGATATTAATATTGCAACCGGTACTACAGATATTGGAAGC-3′; WT_M113G, 5′-CGATTGATACAAAAGAGTATGGGAGTACTTTAACTTATGGATTCAACGG-3′; WT_K131G, 5′-TTACTGGTGATGATACAGGAGGAATTGGCGGCCTTATTGGTG-3′; WT_K147G, 5′-GTTTCGATTGGTCATACACTGGGATATGTTCAACCTGATTTCAAAAC-3′. For G137C-AG, a PCR was carried out with the following four sense primers: K8A, 5′-GCAGATTCTGATATTAATATTGCAACCGGTACTACAGATATTGGAAGC-3′; RL3_M113G, 5′-GAATTCGATTGATACAAAAGAGTATGGGAGTACGTTAACGTACGGATTC-3′; G137C_RL3_K131G, 5′-GTTACTGGTGATGATACAGGAGGAATTGGAGGCCTTATTTGCGC-3′; RL3_K147G, 5′-GTTTCGATTGGTCATACACTTGGGTATGTTCAACCTGATTTCAAAAC-3′. The codons for the mutated amino acid residues are underlined. The AflII restriction site in pT7-G137C-D8-RL3 was removed by the K147G mutation.

The procedure was similar to that suggested in the kit, with slight modifications. Each PCR (25 μL) was set up by mixing the following reagents in the order listed: 10× QuikChange Lightning Multi reaction buffer (2.5 μL), nuclease-free water (to make up the final volume of the reaction to 25 μL), double-stranded plasmid DNA template (50–100 ng), mutagenic primers (∼100 ng of each primer), deoxynucleotide (dNTP) mix (1 μL from the kit), and the QuikChange Lightning Multi enzyme blend (1 μL). The PCRs were carried out with following program: 94°C for 5 min, 18 cycles of 95°C (0.5 min), 55°C (0.5 min), 68°C (9 min), followed by a final extension at 68°C for 7 min. The PCRs were then cooled and the template was digested with DpnI (1 μL, supplied with the kit) at 37°C for 1.5 h. pT7 plasmids containing the mutant genes were generated by transforming Escherichia coli XL-10 Gold ultracompetent cells with the PCR product. The DNA sequences of the genes were verified (Source BioScience).

Further site-directed mutagenesis

The genes αHL L135H/G137C-AG (HC), αHL L135C/G137C-AG (CC), and αHL L135H-AG (H) were constructed by using pT7-G137C-AG (see above) as the template. For the HC gene, two PCRs (Phusion Flash PCR Master Mix, catalog No. F-548S; Finnzymes/Thermo Scientific, Leicestershire, UK) were carried out with the following two sets of primers: first set: mutagenic primer (sense, L135H-G137C-fw) 5′-CAGGAGGAATTGGAGGCCATATTTGCGCAAATGTTTC-3′, nonmutagenic primer (antisense, SC47) 5′-CAGAAGTGGTCCTGCAACTTTAT-3′; second set: mutagenic primer (antisense, L135H-G137C-rev) 5′-GAAACATTTGCGCAAATATGGCCTCCAATTCCTCCTG-3′, nonmutagenic primer (sense, SC46) 5′-ATAAAGTTGCAGGACCACTTCTG-3′. For the CC gene, two PCRs were carried out with the following two sets of primers: first set: mutagenic primer (sense, L135C-G137C-fw) 5′-GATACAGGAGGAATTGGAGGCTGTATTTGCGCAAATGTTTCGAT-3′, nonmutagenic primer (antisense, SC47) 5′-CAGAAGTGGTCCTGCAACTTTAT-3′; second set: mutagenic primer (antisense, L135C-G137C-rev) 5′-ATCGAAACATTTGCGCAAATACAGCCTCCAATTCCTCCTGTATC-3′, nonmutagenic primer (sense, SC46) 5′-ATAAAGTTGCAGGACCACTTCTG-3′. For the H gene, two PCRs were carried out with the following two sets of primers: first set: mutagenic primer (sense, L135H-C137G-fw) 5′-GATACAGGAGGAATTGGAGGCCATATTGGTGCAAATGTTTCGATTGGTC-3′, nonmutagenic primer (antisense, SC47) 5′-CAGAAGTGGTCCTGCAACTTTAT-3′; second set: mutagenic primer (antisense, L135H-C137G-rev) 5′-GACCAATCGAAACATTTGCACCAATATGGCCTCCAATTCCTCCTGTATC-3′, nonmutagenic primer (sense, SC46) 5′-ATAAAGTTGCAGGACCACTTCTG-3′. Notice that in the H gene, Cys-137 is mutated back into the αHL WT residue glycine. The mutated codons are underlined.

The template DNA, pT7-G137C-AG (100 ng μL−1), was linearized with NdeI for the first primer set and with HindIII for the second set. Each PCR (20 μL) was set up by mixing the following reagents: Phusion Flash PCR Master Mix (10 μL, 2×), the digested template DNA (1 μL, 10 ng μL−1), the two primers (1 μL each, 10 μM), and nuclease-free water (7 μL). The PCR reactions were carried out with following program: 98°C for 30 s, 30 cycles of 98°C (10 s), 68°C (5 s), 72°C (40 s), followed by a final extension at 72°C for 60 s. The two PCR products (5 μL each) for a particular mutation were mixed and used to transform E. coli XL-10 Gold cells, which generated the pT7 vector containing the mutant gene by in vivo recombination. The DNA sequences of the genes were verified (Source BioScience).

Protein preparation

The heteroheptameric cysteine-containing αHL pores (PC, PHC, PCC, and PH) were prepared as described by Choi and Bayley (18). PC, PHC, PCC, and PH represent (AG)6(G137C-AG)1, (AG)6(L135H/G137C-AG)1, (AG)6(L135C/G137C-AG)1, and (AG)6(L135H-AG)1 respectively. In brief, pT7 plasmids carrying mutated αHL genes were produced by site-directed mutagenesis (see above). αHL proteins were expressed in the presence of [35S]methionine in an E. coli in vitro transcription and translation (IVTT) system (E. coli T7 S30 Extract System for Circular DNA, catalog No. L1130; Promega, Southampton, UK). Protein expression and oligomerization were carried out simultaneously by resuspending rabbit red blood cell membranes (rRBCm) in the IVTT mixture before incubation at 37°C for 1.5 h. To prepare heteroheptamers (e.g., PC), the plasmid DNAs for AG and G137C-AG were mixed in a 6:1 ratio for IVTT (50 μL). αHL heteroheptamers were purified in a 5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel with 1× Tris-Glycine-SDS (TGS) running buffer under reducing conditions. The gel was dried and the protein bands were visualized by autoradiography. Because the G137C-AG monomer has an extension of eight aspartate residues at the C-terminus (similarly to the L135H/G137C-AG, L135C/G137C-AG, and L135H-AG monomers), but the AG monomer does not, heteroheptamers containing G137C-AG subunits carry more negative charge and migrate more rapidly toward the anode (19). Therefore, the target heteroheptamer, PC, with a 6:1 ratio of AG to G137C-AG corresponds to the band immediately beneath the (AG)7 band on a gel (Fig. 1). The PC band was cut out and rehydrated, and the protein was extracted (18). Purified proteins were stored at –80°C in TE buffer (10 mM Tris.HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) containing 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT).

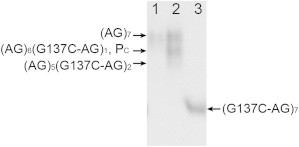

Figure 1.

SDS-PAGE gel (5%) showing the bands corresponding to αHL heptamers. Lane 1: Heptamer made from AG monomer only. Lane 2: Heptamers formed from AG monomer and G137C-AG monomer mixed in a 6:1 ratio. Lane 3: Heptamer comprising G137C-AG monomer only. The identity of each band is indicated.

Planar lipid bilayer recordings

Lipid bilayers were formed from 1,2-diphytanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPhPC; Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL) in a previously described apparatus (20). Buffer solutions (2 M KNO3, 10 mM MOPS, with 10 mM EDTA or treated with Chelex ion-exchange resin, adjusted to pH 7.4 with 1 M KOH) were deoxygenated by purging with N2 for 15–20 min before use. Buffer (1 mL) was added to both compartments of the apparatus and a potential was applied across the bilayer with Ag/AgCl electrodes that were in double-layered agarose bridges. The electrodes were covered with an inner layer of 3 M KCl in 3% low-melting agarose, which was encased in an outer layer of 2 M KNO3 in 3% low-melting agarose. The bridges were necessary because silver ions leach from bare Ag/AgCl electrodes into high-chloride buffer solutions and react with thiol groups of the αHL pore. PC (or PHC, PCC, or PH) was added to the cis compartment (ground) and the applied potential was increased to +140 mV. The cis solution was stirred until a single channel appeared. Due to the denaturing effect of high concentrations of KNO3 (≥1 M) on nonmembrane-associated αHL, αHL was inserted under asymmetrical salt conditions (150 mM KNO3 (cis)/2 M KNO3 (trans), both with same concentration of buffering agent and EDTA). After insertion, portions of the buffer in the cis compartment were replaced with 2.5 M KNO3 buffer until the concentration of KNO3 on the cis side reached 2 M. Current recordings were performed at 22°C ± 1°C with a patch-clamp amplifier (Axopatch 200B; Axon Instruments, now Molecular Devices, Berkshire, UK). The signal was filtered with a low-pass Bessel filter (80 dB/decade) with a corner frequency of 2 kHz, and sampled at 20 kHz with a DigiData 1320 A/D converter (Axon Instruments).

Freshly thawed aliquots of protein were used each day. Stock AgNO3 (1 mM) and Cd(NO3)2 (10 mM) solutions in deionized water were prepared daily. The AgNO3 solution was kept in the dark.

Data analysis of single-channel recordings

Current traces were filtered digitally with a 200 Hz low-pass Bessel filter (eight-pole) in Clampfit 9.2 (Axon Instruments). Events were detected by using the single-channel search feature. The mean dwell times of the current states were determined by fitting dwell-time histograms to single-exponential functions. Further analysis was carried out by using the program QuB (www.qub.buffalo.edu) to determine the rates (s−1) for each transition. The processed data were plotted by using OriginPro 8.1 SR3 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA).

Owing to the low solubility of Ag+ in chloride-containing solutions and the formation of complexes between Ag+ and Cl−, buffer solution containing KNO3 as the electrolyte was used for Ag+ binding studies. Moreover, 10 mM EDTA was present as a buffering agent for Ag+ ion. [Ag+]free was calculated with the program Maxchelator (http://maxchelator.stanford.edu) by using the stability constants appropriate under our conditions. The log10 value of the association constant for Ag+ ion and the fully deprotonated form of EDTA is 7.32 ± 0.05 (22). The six pKa values of EDTA are incorporated into the program (4, 8, 16, and 32 μM of added AgNO3 correspond to 16, 33, 66, and 133 nM [Ag+]free). Similar values for [Ag+]free were obtained with the program ALEX (23). Cd2+ binding was carried out in EDTA-free buffer; [Cd2+]free is assumed to be the same as the total concentration of Cd(NO3)2 added.

Results and Discussion

Design of the αHL mutant for metal ion detection

The homoheptameric wild-type αHL pore (WT)7, which contains no cysteine residues, interacted with the metal ions under examination. In particular, Ag+ bound reversibly to (WT)7. This is presumably due to the affinity of Ag+ for amino acid side chains in the pore lumen that contain nitrogen or sulfur atoms (24–27), such as those of lysine, arginine, histidine, and methionine. Therefore, potentially interacting residues located in the narrower regions of the lumen (the cis entrance and the β barrel) were mutated to noninteracting residues such as glycine and alanine. Other potentially interacting residues located in the wider vestibule region of the lumen and on the exterior of the pore were not mutated, because metal ion binding to these residues was not expected to cause detectable events. On this basis, the mutant αHL AG, which contains four point mutations (K8A/M113G/K131G/K147G), was designed (Fig. 2). Gratifyingly, (AG)7 did not interact with Ag+ and Cd2+, and therefore it was used to provide the noise-free background for this study.

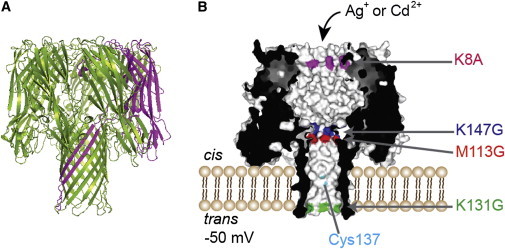

Figure 2.

Structures of the αHL pores used for the metal-binding studies. (A) WT αHL is a mushroom-shaped transmembrane protein pore made of seven identical, cysteine-free subunits. A side view of the ribbon structure (PDB code 7AHL) is shown. One of the seven subunits is highlighted in magenta. (B) αHL pore embedded in a planar lipid bilayer for single-channel electrical recording. A cross section of PC is shown. PC contains one subunit (of seven) with a cysteine residue at position 137 (highlighted in cyan and labeled), which is located in the middle of the transmembrane β barrel with the side chain pointing toward the lumen. Four mutations (K8A, M113G, K131G, and K147G) were introduced into WT αHL by site-directed mutagenesis to create the AG background on which PC is based. The locations of the four mutations are highlighted and indicated. Metal ions (Ag+ or Cd2+) were added to the cis compartment, which is the side where the cap domain of the αHL pore resides and is connected to ground. During measurements, a potential of –50 mV was applied to the trans compartment relative to the cis compartment.

Based on this finding, a heteroheptameric αHL pore PC with one cysteine-containing subunit (αHL G137C-AG) and six cysteine-free subunits (αHL AG; Fig. 2) was prepared. The side chain of the single cysteine residue points into the water-filled lumen of the pore.

Ag+ binding

Ag+ ([Ag+]free, 16–133 nM) added to the cis side of a bilayer containing a single PC pore at –50 mV and pH 7.4 (2 M KNO3, 10 mM MOPS, 10 mM EDTA) generates reversible blockades that show two current levels relative to the unoccupied pore (ΔI = 1.6 ± 0.3 pA (level 1) and ΔI = 3.6 ± 0.6 pA (level 2); n = 3; Fig. 3 A). The frequency of occurrence of these blockades increases with [Ag+]free, and at higher [Ag+]free, level 2 becomes more prominent than level 1. Transitions between unoccupied PC (level 0) and level 2 always pass through level 1; direct transitions are not observed.

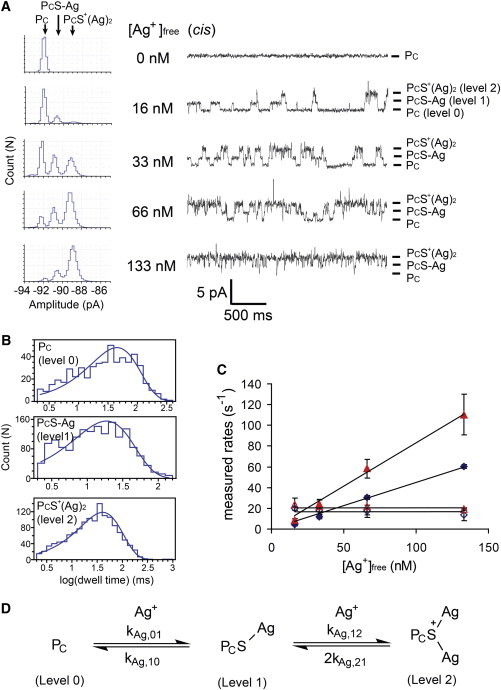

Figure 3.

Reversible and sequential binding of two Ag+ ions to a single cysteine residue. (A) Current recordings at different free Ag+ ion concentrations, [Ag+]free (Ag+ was added as AgNO3 to the cis compartment). Each current level is labeled on the right: PC = unoccupied pore (level 0); PCS-Ag = one Ag+ ion-bound (level 1); PCS+(Ag)2 = two Ag+ ions-bound (level 2). All-points amplitude histograms are shown on the left. Conditions: 2 M KNO3, 10 mM MOPS, 10 mM EDTA, pH 7.4, at 22°C and –50 mV. Under these conditions, PC has an open pore current of –96 ± 2 pA (n = 5). (B) Dwell-time histograms for PC, PCS-Ag, and PCS+(Ag)2 in the presence of 66 nM [Ag+]free. Each histogram was fitted to a single-exponential function using Clampfit (Molecular Devices) to determine the mean dwell time . (C) Plots of the measured rates of each transition versus [Ag+]free. Each data point (mean ± SD) was obtained from three experiments: level 0→level 1 (blue solid rhombus), level 1→0 (blue open rhombus), level 1→2 (red solid triangle), level 2→1 (red open triangle). The determination of rate constants from these plots is described in the Materials and Methods section. (D) Kinetic scheme describing the sequential association of two Ag+ ions with the cysteine side chain in PC. Direct transitions between PC and PCS+(Ag)2 are not observed. This scheme was used in QuB (see Materials and Methods) for the determination of rate constants.

The rate constants for the transitions (Table 1) were determined from plots of the measured rates versus [Ag+]free (Fig. 3 C, see also the Materials and Methods section), with the assumption that [Ag+]free inside the pore is the same as that in bulk solution. Both the transition rate (v) from level 0 to level 1 (0→1) and that from level 1 to level 2 (1→2) have a first-order dependence on [Ag+]free: v01 = kAg,01[Ag+]free and v12 = kAg,12[Ag+]free, where kAg,01 = (4.4 ± 0.3) × 108 M−1s−1 and kAg,12 = (8.3 ± 1.3) × 108 M−1s−1), whereas both 1→0 and 2→1 are independent of [Ag+]free: v10 = kAg,10 and v21 = kAg,21, where kAg,10 = 17 ± 1 s−1 and kAg,21 = 11 ± 3 s−1 (n = 3; Fig. 3 D). The first and second equilibrium dissociation constants calculated from these data are Kd,Ag,1 = kAg,10/kAg,01 = (4.0 ± 0.5) × 10−8 M and Kd,Ag,2 = kAg,21/kAg,12 = (1.3 ± 0.3) × 10−8 M (Table 1). The overall Kd for Ag+ binding = Kd,Ag,1.Kd,Ag,2 = (5.3 ± 1.4) × 10−16 M2.

Table 1.

Association and dissociation rate constants, and equilibrium dissociation constants for Ag+ and Cd2+ with the PC, PHC, and PCC pores

| Mutant | Current blockade (ΔI) (pA) | Association rate constant (M−1s−1) | Dissociation rate constant (s−1) | Equilibrium dissociation constant (M)e | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag+ | PCa (n = 3) | 1.6 ± 0.3 | kAg,01c (4.4 ± 0.3) × 108 | kAg,10c 17 ± 1 | Kd,Ag,1 (4.0 ± 0.5) × 10−8 |

| 3.6 ± 0.6 | kAg,12c (8.3 ± 1.3) × 108 | kAg,21c 11 ± 3 | Kd,Ag,2 (1.3 ± 0.3) × 10−8 | ||

| Cd2+ | PCb (n = 4) | 3.8 ± 0.1 | kCd,01 (5.9 ± 0.6) × 104 | kCd,10 13 ± 1 | Kd,Cd (2.2 ± 0.4) × 10−4 |

| PCCb (n = 3) | 1.4 ± 0.2 | kappCC,01d (5.3 ± 1.8) × 104 | kappCC,10d (3.5 ± 0.5) × 10−2 | Kappd,CC (6.5 ± 2.4) × 10−7 | |

| PHCb (n = 3) | 4.9 ± 0.6 | kappHC,01d (1.3 ± 0.3) × 106 | kappHC,10d 9.2 ± 2.5 | Kappd,HC (6.8 ± 2.4) × 10−6 |

Conditions for Ag+: pH 7.4 (2 M KNO3, 10 mM MOPS, 10 mM EDTA) at −50 mV and 22°C. Conditions for Cd2+: pH 7.4 (2 M KNO3, 10 mM MOPS, Chelex treated) at −50 mV and 22°C. Values (mean ± SD) were calculated by using the concentration of free Ag+ ion or the total concentration of Cd2+ ion.

PC binds two Ag+ ions.

The association of Cd2+ to these mutants shows bimolecular kinetics with first-order dependencies on [Cd2+]. Binding of a second Cd2+ is not observed.

For definitions, see the kinetic schemes in Fig. 3D.

These values are the rate constants calculated directly from the experimental data (see Figs. 7 and 8). They can be resolved into the rate constants of individual steps. Refer to the Supporting Material for more details.

The equilibrium dissociation constant equals the dissociation rate constant divided by the association rate constant from the same row of the table.

Because a Ag+ ion is involved in both the 0→1 and the 1→2 transitions, levels 1 and 2 are proposed to be PC-S-Ag and PCS+(Ag)2, respectively (Fig. 3 D). A thiolate sulfur atom can bridge two Ag+ ions (28). Therefore, level 2 is believed to represent Ag-S+(PC)-Ag rather than PC-S-Ag+-Ag (with a bridging Ag), which is supported by the absence of direct transitions between PCS+(Ag)2 and PC (i.e., 2↔0 does not occur).

In addition to reversible Ag+ binding, Ag+-induced complete blockade of the PC pore was frequently observed: 64% of experiments (87 out of 136) showed complete blockade within 10 min after the addition of a submicromolar concentration of free Ag+ ion (Fig. 4, A and B). The blockade was usually stepwise and the process was completed <30 s after its initiation. Such blockades could be reversed by the addition of excess thiol (more than one equivalent of thiol compound relative to the total AgNO3 added), such as DTT, cysteamine, or β-mercaptoethanol, to either the cis or trans compartment. Pore unblocking occurred in a single step (Fig. 4 C) or by a stepwise (Fig. 4 D) mechanism. Full blockade arose again if the concentration of thiol was diluted to ∼100 nM. If ∼100 nM thiol (e.g. cysteine, thioglycolate, and cysteamine) was present initially, the onset of the Ag+ ion-induced current blockade took place with a shorter lag time while showing similar blocking characteristics (see Supporting Material). The complete blockade, with or without added thiol, usually begins from the single Ag(I)-bound state (PC-S-Ag; see Fig. 4 B). Blockade did not occur with αHL (AG)7, showing that a lumenal cysteine side chain is required. Because residual thiols from the protein preparation (thioglycolate, β-mercaptoethanol, and DTT, at the tens of nanomolar level) were present during planar lipid bilayer experiments, we propose that the blockade of PC arises from the formation of Ag+-thiol coordination polymers on the cysteine thiol group (29,30) (Fig. S2). Because Ag+-thiol polymers form reversibly in solution (31), the addition of excess thiol breaks protein-bound polymers into shorter chains, which diffuse away, thereby unblocking the pore. Whether the unblocking process occurs as a single step (Fig. 4 C) or multiple steps (Fig. 4 D) depends on the initial site of polymer cleavage.

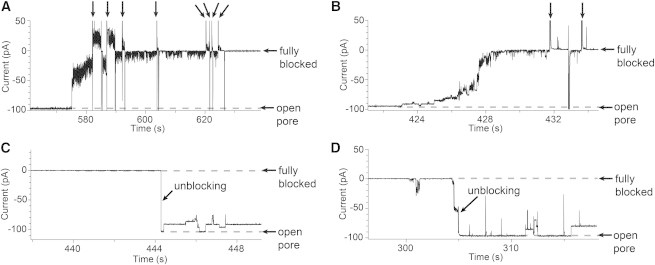

Figure 4.

Complete blockade of PC by AgNO3. (A and B) Full blockade of PC after the addition of AgNO3 (cis, 33 nM free Ag+ ion). Soon after the appearance of reversible Ag+ ion binding events as shown in Fig. 3A, PC underwent a stepwise decrease in conductance, which eventually led to complete blockade (64% of experiments exhibited full blockade). The applied potential was switched to +50 mV as indicated by black arrows on the current traces. In A, a sudden large drop in conductance was first observed, followed by a stepwise decrease in conductance. In B, a stepwise decrease in conductance from the open pore level to the fully blocked level was seen. The noise in the intermediate levels may be caused by polymer movement (35,36). (C and D) Reopening of blocked PC. After the full blockade induced by AgNO3, cysteamine was added to the cis compartment. More than one equivalent of cysteamine (10 μM) relative to the total amount of AgNO3 (cis, 8 μM) was necessary for unblocking. Cysteamine forms oligomers with Ag+ ion in solution (37). The oligomers occasionally react with the protein cysteine residue, leading to additional incomplete blockades. Panels C and D show one-step and stepwise unblocking, respectively.

Implications for the use of Ag+ in SCAM

In macroscopic studies of ion channels (e.g., the P2X purinoreceptor (32), Shaker K+ channel (3), and cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNG) channel (33)), Ag+ binds to exposed cysteine thiols with apparent bimolecular rate constants of up to 108 M−1s−1 (32). The binding is effectively irreversible because the removal of Ag+ does not reverse the blockade over at least 5 s. Our association rate constants (kAg,01 = (4.4 ± 0.3) × 108 M−1s−1 and kAg,12 = (8.3 ± 1.3) × 108 M−1s−1 for PC) are similar to the maximum rate constants observed in ion channel studies, consistent with the side chain of Cys-137 being water accessible. However, in contrast to the findings with ion channels, reversible coordination of two Ag+ ions is observed in our single-molecule experiments. Because kAg,12 > kAg,01, binding as measured in macroscopic current recordings would be described by a single exponential. Alternatively, the first Ag+ ion might block the narrow conductive pathway of an ion channel completely, thereby producing a one-step bimolecular blockade. Finally, with regard to permanent blockade, it should be noted that most ion channels investigated by SCAM comprise more than one cysteine-containing subunit, and the coordination of Ag+ by proximal thiol groups contributed by adjacent subunits or by the side chains of additional amino acids (e.g., histidine) might lead to irreversible obstruction of the conductive pathway.

Cd2+ binding

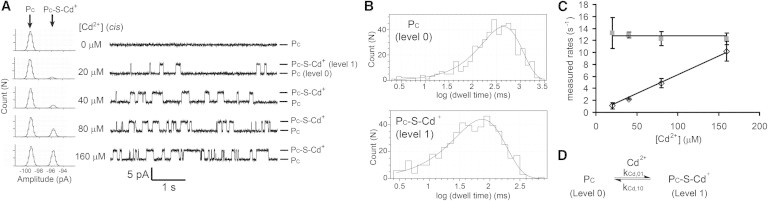

By contrast, Cd2+ (20–160 μM) added to PC at –50 mV and pH 7.4 (2 M KNO3, 10 mM MOPS) provoked reversible blockades with just one new level: ΔI = 3.8 ± 0.1 pA (n = 4; Fig. 5 A). The association of Cd2+ was bimolecular with v01 = kCd,01[Cd2+], where kCd,01 = (5.9 ± 0.6) × 104 M−1s−1, whereas dissociation was unimolecular with v10 = kCd,10, where kCd,10 = 13 ± 1 s−1 (n = 4; Fig. 5 C). Therefore, level 1 (Fig. 5 A) is assigned the structure PC-S-Cd+ (Fig. 5 D). The equilibrium dissociation constant is Kd,Cd = kCd,10/kCd,01 = (2.2 ± 0.4) × 10−4 M (n = 4; Table 1).

Figure 5.

Reversible binding of Cd2+ ion to PC. (A) Stacked current traces for PC at different concentrations of Cd(NO3)2 ([Cd2+], cis). Each level is labeled on the right: PC, open pore; PCS-Cd+, pore with Cd2+-bound. All-points amplitude histograms are shown on the left. The histograms are fitted to the sum of two Gaussian functions. Conditions: 2 M KNO3, 10 mM MOPS, treated with Chelex ion exchange resin, pH 7.4, at –50 mV and 22°C. (B) Dwell-time histograms of PC and PCS-Cd+ in the presence of 40 μM Cd(NO3)2. Each histogram was fitted to a single-exponential function using Clampfit (Molecular Devices) to determine the mean dwell time . (C) Plots of the measured rates of each transition (as the reciprocals of the mean dwell times for the open pore (, black open rhombus) and the Cd2+-occupied pore (, gray solid square)) versus [Cd2+]. Each data point (mean ± SD) was obtained from four experiments. (D) Kinetic scheme describing the binding of Cd2+ to PC.

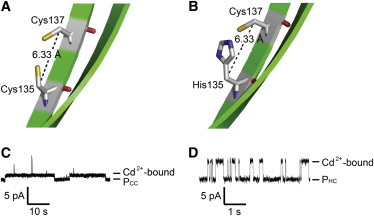

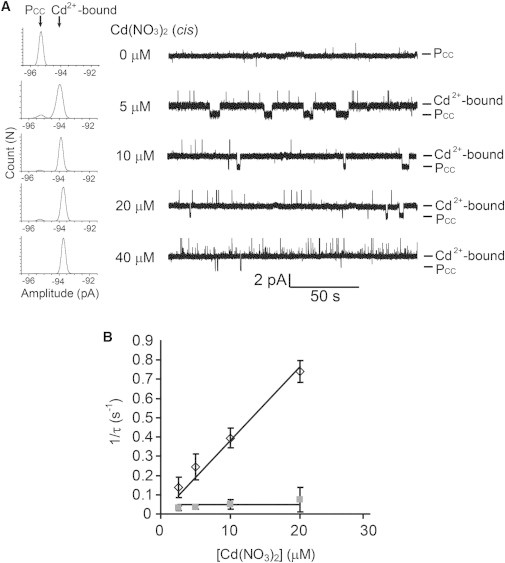

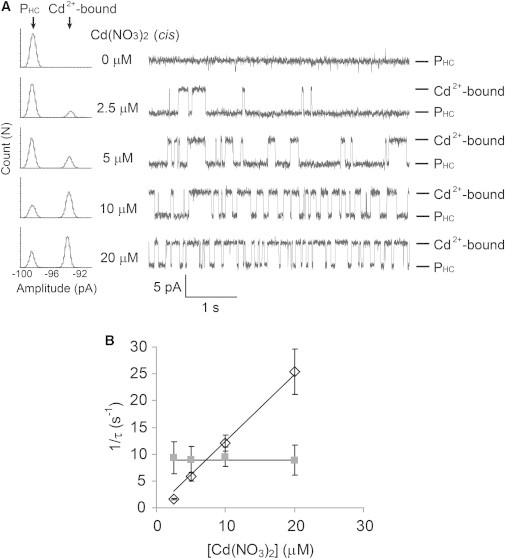

The binding of Cd2+ to cysteine side chains in ion channels is strengthened by the presence of additional coordinating ligands (5,32). To create such a chelation site in the αHL pore, an additional cysteine or histidine residue was introduced in the AG background at position 135, which is adjacent to Cys-137 on the same β strand (Fig. 6). The heteroheptameric pores formed with each of these two mutants were termed PCC and PHC. Single-molecule kinetic analysis showed that both PCC and PHC bind one Cd2+, but do so more tightly than PC (Table 1; Figs. 7 and 8). Apparent bimolecular association kinetics were observed. No half-liganded intermediates were seen, and therefore the second coordination step must be fast, which is in contrast to the binding of Zn2+ by an αHL pore equipped with two iminodiacetate ligands (14). The coordination of a second Cd2+ ion was not detected.

Figure 6.

Chelation sites for Cd2+ within the αHL pore. (A) Cys-135/Cys-137 (PCC). (B) His-135/Cys-137 (PHC). Positions 135 and 137 are located on a transmembrane β strand of αHL (see Fig. 2); both have their amino acid side chains pointing toward the pore lumen. The Cβ–Cβ distance between positions 135 and 137 is 6.3 Å (11). The orientations of the Cβ-S and Cβ-imidazole bonds are for illustration purposes only. The two antiparallel β strands of one αHL protomer are shown. (C and D) Current recordings showing the reversible association of Cd2+ with (C) PCC and (D) PHC at 5 μM Cd(NO3)2 (cis). Note that the time bar in C is 10 times longer than that in D.

Figure 7.

Reversible binding of Cd2+ to PCC. (A) Stacked current recording traces of PCC, (AG)6(L135C/G137C-AG)1, at various concentrations of Cd(NO3)2 (cis), as labeled on the left of the traces. The conditions were the same as in Fig. 5. Only two current levels were observed, namely, the open pore (PCC) and the pore with Cd2+ bound, as labeled on the right of the traces. All-points amplitude histograms are shown to the far left. The histograms are fitted to the sum of two Gaussian functions. (B) Reciprocals of the mean dwell times for the unoccupied pore (, black open rhombus) and the pore with bound Cd2+ (, gray solid square) versus the concentration of Cd(NO3)2. Each data point is the mean ± SD from three repeats. The association and dissociation of Cd2+ follow simple bimolecular and unimolecular kinetics, respectively. The binding of a second Cd2+ is not observed.

Figure 8.

Reversible binding of Cd2+ to PHC. (A) Stacked current recording traces of PHC, (AG)6(L135H/G137C-AG)1, at various concentrations of Cd(NO3)2 (cis) as labeled on the left of the traces. The conditions were the same as in Fig. 5. Only two levels were observed, namely, the open pore (PHC) and a level with bound Cd2+, as indicated on the right of the traces. All-points amplitude histograms are shown to the far left. The histograms are fitted to the sum of two Gaussian functions. (B) Reciprocals of the mean dwell times of the unoccupied pore (, black open rhombus) and the pore with bound Cd2+ (, gray solid square) versus the concentration of Cd(NO3)2. Each data point is the mean ± SD from three repeats. The association of Cd2+ with PHC demonstrates simple bimolecular kinetics with a first-order dependence on [Cd2+], whereas the dissociation is unimolecular and independent of [Cd2+]. The binding of a second Cd2+ is not observed.

Compared with PC, Cd2+ shows 22 times faster association with PHC (kappHC,01 = (1.3 ± 0.3) × 106 M−1s−1) and 370 times slower dissociation from PCC (kappCC,10 = (3.5 ± 0.5) × 10−2 s−1) (Table 1). Dissociation from PHC (kappHC,10 = 9.2 ± 2.5 s−1) and association with PCC (kCC,01 = (5.3 ± 1.8) × 104 M−1s−1) have rate constants similar to the corresponding values for PC. The increased apparent association rate constant for PHC may arise either from the lowering of the pKa of Cys-137 by the adjacent imidazole ring to favor the reactive thiolate or from the rapid initial coordination of Cd2+ by the imidazole ring (for discussion, see Supporting Material). The decreased apparent dissociation rate constant for PCC results either from the rapid coordination of Cd2+ bound to a first thiol by the second protein thiol or from the slow cleavage of the first Cd-S bond in the fully coordinated complex (see Supporting Material). These chelate effects lead to a 30-fold tighter binding of Cd2+ to PHC (Kd,HC = (6.8 ± 2.4) × 10−6 M) and 300-fold tighter binding to PCC (Kd,CC = (6.5 ± 2.4) × 10−7 M) compared with PC. The Kd values and the increase in binding affinity by an additional Cys or His ligand are in agreement with previous findings obtained with β-strand or α-helical peptides (34).

Conclusions

The rate of modification of cysteine residues by thiophilic reagents is the primary readout obtained from SCAM. The correct interpretation of these data, which relies on an understanding of the modification reactions, is therefore pivotal for deciphering the topology of ion channels in different conformations. In this work, we determined the coordination stoichiometries and kinetics of the two most important metal ion probes, Ag+ and Cd2+, with respect to cysteine thiol groups at the single-molecule level, and established the αHL pore as a platform on which new reagents can be tested. We also hope that our findings will guide single-molecule studies of ion channels with thiophilic metal ions, which could provide better structural information than macroscopic studies. Our findings suggest that Cd2+, which binds to thiols in a simple bimolecular fashion, and for which neighboring Cys and His residues have predictable effects, might be the metal ion of choice for such work.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Lajos Höfler for help with the noise analysis. This work was supported by a European Research Council Advanced Grant and Oxford Nanopore Technologies. Lai-Sheung Choi was the recipient of a University of Oxford Croucher Scholarship. Hagan Bayley is the founder, a director, and a shareholder of Oxford Nanopore Technologies.

Footnotes

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons-Attribution Noncommercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Karlin A., Akabas M.H. Substituted-cysteine accessibility method. Methods Enzymol. 1998;293:123–145. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)93011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vinothkumar K.R., Henderson R. Structures of membrane proteins. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2010;43:65–158. doi: 10.1017/S0033583510000041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lü Q., Miller C. Silver as a probe of pore-forming residues in a potassium channel. Science. 1995;268:304–307. doi: 10.1126/science.7716526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pérez-García M.T., Chiamvimonvat N., Tomaselli G.F. Structure of the sodium channel pore revealed by serial cysteine mutagenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:300–304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webster S.M., Del Camino D., Yellen G. Intracellular gate opening in Shaker K+ channels defined by high-affinity metal bridges. Nature. 2004;428:864–868. doi: 10.1038/nature02468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Preston G.M., Jung J.S., Agre P. The mercury-sensitive residue at cysteine 189 in the CHIP28 water channel. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:17–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akabas M.H., Stauffer D.A., Karlin A. Acetylcholine receptor channel structure probed in cysteine-substitution mutants. Science. 1992;258:307–310. doi: 10.1126/science.1384130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shannon R.D. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Acta Crystallogr. A. 1976;32:751–767. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lincoln S.F., Richens D.T., Sykes A.G. Metal aqua ions. In: Lever A.B.P., McCleverty J.A., Meyer T.J., editors. Comprehensive Coordination Chemistry. II: From Biology to Nanotechnology, Vol. 1. Elsevier; Amsterdam/Oxford: 2004. pp. 515–556. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmgren M., Shin K.S., Yellen G. The activation gate of a voltage-gated K+ channel can be trapped in the open state by an intersubunit metal bridge. Neuron. 1998;21:617–621. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80571-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song L., Hobaugh M.R., Gouaux J.E. Structure of staphylococcal α-hemolysin, a heptameric transmembrane pore. Science. 1996;274:1859–1866. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5294.1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bayley H., Luchian T., Steffensen M.B. Single-molecule covalent chemistry in a protein nanoreactor. In: Rigler R., Vogel H., editors. Single Molecules and Nanotechnology. Springer; Heidelberg: 2008. pp. 251–277. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braha O., Gu L.-Q., Bayley H. Simultaneous stochastic sensing of divalent metal ions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18:1005–1007. doi: 10.1038/79275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hammerstein A.F., Shin S.-H., Bayley H. Single-molecule kinetics of two-step divalent cation chelation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2010;49:5085–5090. doi: 10.1002/anie.200906601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walker B., Krishnasastry M., Bayley H. Functional expression of the α-hemolysin of Staphylococcus aureus in intact Escherichia coli and in cell lysates. Deletion of five C-terminal amino acids selectively impairs hemolytic activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:10902–10909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shin S.-H., Steffensen M.B., Bayley H. Formation of a chiral center and pyrimidal inversion at the single-molecule level. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2007;46:7412–7416. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wolfe A.J., Mohammad M.M., Movileanu L. Catalyzing the translocation of polypeptides through attractive interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:14034–14041. doi: 10.1021/ja0749340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Choi L.-S., Bayley H. S-nitrosothiol chemistry at the single-molecule level. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012;51:7972–7976. doi: 10.1002/anie.201202365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shin S.-H., Luchian T., Cheley S., Braha O., Bayley H. Kinetics of a reversible covalent-bond-forming reaction observed at the single molecule level. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2002;41:3707–3709. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20021004)41:19<3707::AID-ANIE3707>3.0.CO;2-5. 3523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu S., Li W.-W., Bayley H. A primary hydrogen-deuterium isotope effect observed at the single-molecule level. Nat. Chem. 2010;2:921–928. doi: 10.1038/nchem.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reference deleted in proof.

- 22.Martell A.E., Smith R.M. Plenum Press; New York/London: 1974. Critical Stability Constants. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vivaudou M.B., Arnoult C., Villaz M. Skeletal muscle ATP-sensitive K+ channels recorded from sarcolemmal blebs of split fibers: ATP inhibition is reduced by magnesium and ADP. J. Membr. Biol. 1991;122:165–175. doi: 10.1007/BF01872639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gruen L.C. Interaction of amino acids with silver(I) ions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1975;386:270–274. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(75)90268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee V.W.-M., Li H., Siu K.W.M. Relative silver(I) ion binding energies of α-amino acids: a determination by means of the kinetic method. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 1998;9:760–766. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shoeib T., Siu K.W.M., Hopkinson A.C. Silver ion binding energies of amino acids: use of theory to assess the validity of experimental silver ion basicities obtained from the kinetic method. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2002;106:6121–6128. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jover J., Bosque R., Sales J. A comparison of the binding affinity of the common amino acids with different metal cations. Dalton Trans. 2008;45:6441–6453. doi: 10.1039/b805860a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dance I.G., Fitzpatrick L.J., Scudder M.L. The intertwined double-(-Ag-SR-)∞-strand chain structure of crystalline (3-methylpentane-3-thiolato)silver, in reaction to (AgSR)8 molecules in solution. Inorg. Chem. 1983;22:3785–3788. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nan J., Yan X.-P. A circular dichroism probe for L-cysteine based on the self-assembly of chiral complex nanoparticles. Chemistry. 2010;16:423–427. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen J.-S., Li D.-H., Jiang Y.B. Metal-metal-interaction-facilitated coordination polymer as a sensing ensemble: a case study for cysteine sensing. Langmuir. 2011;27:481–486. doi: 10.1021/la103153e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen J.-S., Li D.-H., Jiang Y.-B. Highly selective iodide-responsive gel-sol state transition in supramolecular hydrogels. J. Mater. Chem. 2009;19:6219–6224. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li M., Kawate T., Silberberg S.D., Swartz K.J. Pore-opening mechanism in trimeric P2X receptor channels. Nat. Commun. 2010;1:44. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flynn G.E., Zagotta W.N. Conformational changes in S6 coupled to the opening of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. Neuron. 2001;30:689–698. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00324-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Puljung M.C., Zagotta W.N. Labeling of specific cysteines in proteins using reversible metal protection. Biophys. J. 2011;100:2513–2521. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Movileanu L., Howorka S., Bayley H. Detecting protein analytes that modulate transmembrane movement of a polymer chain within a single protein pore. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18:1091–1095. doi: 10.1038/80295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shin S.-H., Bayley H. Stepwise growth of a single polymer chain. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:10462–10463. doi: 10.1021/ja052194u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andersson L.-O. Study of some silver-thiol complexes and polymers: stoichiometry and optical effects. J. Polym. Sci. A1. 1972;10:1963–1973. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Greenwood N.N., Earnshaw A. Pergamon Press; New York: 1984. Chemistry of the Elements. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Colquhoun D., Hawkes A.G. The principles of the stochastic interpretation of ion-channel mechanisms. In: Sakmann B., Nehre E., editors. Single-Channel Recording. Springer; New York/London: 2009. pp. 397–482. [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeFelice L.J. Plenum Press; New York: 1981. Introduction to Membrane Noise. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verveen A.A., DeFelice L.J. Membrane noise. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 1974;28:189–265. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(74)90019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.