Abstract

The sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) is a critical pathway by which sensory neurons sequester cytosolic Ca2+ and thereby maintain intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis. We have previously demonstrated decreased intraluminal endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ concentration in traumatized sensory neurons. Here we examine SERCA function in dissociated sensory neurons using Fura-2 fluorometry. Blocking SERCA with thapsigargin (1 μM) increased resting [Ca2+]c and prolonged recovery (τ) from transients induced by neuronal activation (elevated bath K+), demonstrating SERCA contributes to control of resting [Ca2+]c and recovery from transient [Ca2+]c elevation. To evaluate SERCA in isolation, plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase was blocked with pH 8.8 bath solution and mitochondrial buffering was avoided by keeping transients small (≤400 nM). Neurons axotomized by spinal nerve ligation (SNL) showed a slowed rate of transient recovery compared to control neurons, representing diminished SERCA function, whereas neighboring non-axotomized neurons from SNL animals were unaffected. Injury did not affect SERCA function in large neurons. Repeated depolarization prolonged transient recovery, showing that neuronal activation inhibits SERCA function. These findings suggest that injury-induced loss of SERCA function in small sensory neurons may contribute to the generation of pain following peripheral nerve injury.

Keywords: sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase, Ca2+ homeostasis, neuropathic pain, endoplasmic reticulum, sensory neuron

INTRODUCTION

Intracellular Ca2+ levels ([Ca2+]c) regulate neuronal excitability, release of neurotransmitters, cell differentiation and apoptosis (Ghosh and Greenberg, 1995; Mata and Sepulveda, 2005). Thus, dysregulation of [Ca2+]c signaling leads to diverse neuropathological conditions (Fernyhough and Calcutt, 2010; Gleichmann and Mattson, 2011; Stutzmann and Mattson, 2011). Neuronal activation triggers an influx of Ca2+ through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCCs), requiring buffering, sequestration, and ultimately Ca2+ efflux to reestablish Ca2+ homeostasis. Efflux pathways include the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA) and the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) (Benham et al., 1992; Suzuki et al., 2002; Usachev et al., 2002; Guerini et al., 2005; Lytton, 2007), while sequestration of Ca2+ into organelle compartments is achieved by the sarcoendoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA), mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter, and secretory pathway Ca2+/Mn2+-ATPases (SPCA) (Fierro et al., 1998; Wuytack et al., 2002; Verkhratsky, 2004, 2005; Usachev et al., 2006; Sepulveda et al., 2007; Brini and Carafoli, 2009).

We have previously demonstrated that painful peripheral nerve injury is associated with aberrant Ca2+ signaling in peripheral sensory neurons after axotomy, including reduced resting [Ca2+]c (Fuchs et al., 2005), diminished activity-induced transients (Fuchs et al., 2007), and accelerated store-operated Ca2+ channel (SOCC) function (Gemes et al., 2011). Also, releasable Ca2+ stored in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is depleted and the concentration of Ca2+ in the ER lumen ([Ca2+]L) is depressed by injury in small sensory neurons (Rigaud et al., 2009). The [Ca2+]L is set by the dynamic balance between SERCA and constitutive Ca2+ leakage from the ER through poorly defined channels (Camello et al., 2002). Our prior finding of normal Ca2+ release channel function after injury (Rigaud et al., 2009) suggests compromised SERCA performance as the cause of decreased [Ca2+]L in injured neurons.

SERCA is the principal high-affinity sequestration pathway for Ca2+ that enters during neuronal activation (Verkhratsky, 2005), and accounts for the most of intracellular uptake during low amplitude [Ca2+]c transients that are insufficient to engage mitochondrial buffering (Usachev et al., 2006). Normal SERCA function is required to maintain intracellular stores that provide releasable Ca2+, which in turn regulates neuronal excitability (Gemes et al., 2011). SERCA dysfunction contributes to numerous pathological conditions, including diabetic axonopathy (Zherebitskaya et al., 2012), Ca2+ overload during neuronal ischemia (Larsen et al., 2005; Henrich and Buckler, 2008), age-associated neuronal degeneration (Pottorf et al., 2000a,b), excitotoxicity (Fernandes et al., 2008), ER stress and apoptosis (Mengesdorf et al., 2001; Verkhratsky, 2004; Gallego-Sandin et al., 2011). Little is known about the modulation of SERCA function after peripheral nerve injury or its role in chronic pain.

To characterize the effect of neuronal trauma, we have measured SERCA function in rats subjected to spinal nerve ligation (SNL) (Kim and Chung, 1992; Hogan et al., 2004), which provides neuronal populations that are axotomized (in the fifth lumbar dorsal root ganglion – L5 DRG), versus the neighboring fourth DRG (L4) neurons that are intact but exposed to inflammation caused by degeneration of the detached distal L5 fiber segments (Gold, 2000). To isolate SERCA, we blocked PMCA, which is the main efflux pathway in neurons (Benham et al., 1992; Usachev et al., 2002).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

All methods and use of animals were approved by the Medical College of Wisconsin Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male Sprague–Dawley rats (Taconic Farms Inc., Hudson, NY, USA) were housed individually in a room maintained at 22±0.5 °C and constant humidity (60±15%) with an alternating 12-h-light–dark cycle. Food and water were available ad libitum throughout the experiments.

Injury model

Rats weighing 150–180 g were subjected to SNL modified from the original technique (Kim and Chung, 1992). Specifically, rats were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane in oxygen and the right paravertebral region was exposed. The L6 transverse process was removed, after which the L5 and L6 spinal nerves were ligated with 6-0 silk suture and transected distal to the ligature. To minimize non-neural injury, no muscle was removed, muscles and intertransverse fascia were incised only at the site of the two ligations, and articular processes were not removed. The muscular fascia was closed with 4-0 resorbable polyglactin sutures and the skin closed with staples. Control animals received skin incision and closure only. After surgery, rats were returned to their cages and kept under normal housing conditions with access to pellet food and water ad lib.

Sensory testing

We measured the incidence of a pattern of hyperalgesic behavior that we have previously documented to be associated with conditioned place avoidance (Hogan et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2010). Briefly, on three different days between 10 and 17 days after surgery, right plantar skin was touched (10 stimuli/test) with a 22-G spinal needle with adequate pressure to indent but not penetrate the skin. Whereas control animals respond with only a brief reflexive withdrawal, rats following SNL may display a complex hyperalgesia response that includes licking, chewing, grooming and sustained elevation of the paw. The average frequency of hyperalgesia responses over the 3 testing days was tabulated for each rat. After SNL, only rats that displayed a hyperalgesia-type response after at least 20% of stimuli were used further in this study.

Neuron isolation and plating

Neurons were rapidly harvested from L4 and L5 DRGs during isoflurane anesthesia and decapitation 21–28 days after SNL or skin sham surgery. This interval was chosen since hyperalgesia is fully developed by this time (Hogan et al., 2004). Ganglia were incubated in 0.5 mg/ml Liberase TM (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) in DMEM/F12 with glutaMAX (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) for 30 min at 37 °C, followed with 1 mg/ml trypsin (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 150 Kunitz units/ml DNase (Sigma–Aldrich) for another 10 min. After addition of 0.1% trypsin inhibitor (Type II, Sigma–Aldrich), tissues were centrifuged, lightly triturated in neural basal media (1X) (Life Technologies) containing 2% (v:v) B27 supplement (50x) (Life Technologies), 0.5 mM glutamine (Sigma–Aldrich), 0.05 mg/ml gentamicin (Life Technologies) and 10 ng/ml nerve growth factor 7S (Alomone Labs Ltd., Jerusalem, Israel). Cells were then plated onto poly-L-lysine (70–150 kDa, Sigma–Aldrich) coated glass cover slips (Deutsches Spiegelglas, Carolina Biological Supply, Burlington, NC, USA) and incubated at 37 °C in humidified 95% air and 5% CO2 for 2 h and were studied 3–8 h after dissociation.

Solutions and agents

Unless otherwise specified, the bath contained Tyrode’s solution (in mM): NaCl 140, KCl 4, CaCl2 2, Glucose 10, MgCl2 2, HEPES 10, with an osmolarity of 297–300 mOsm and pH 7.40. In some experiments, a modified Tyrode’s was used that contained 0.25 mM CaCl2 to generate transient amplitude to smaller than 400 nM after PMCA blockade. To block PMCA, HEPES was replaced by Trizma (10 mM) in regular Tyrode’s with adjusted pH at 8.8 (Duman et al., 2008).

Fura-2-AM was obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA), and the SERCA blocker thapsigargin (TG) and SOCC blocker lanthanum chloride from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Selective VGCC subtype antagonists including nimodipine (5 μM) to block L-type current (Wu et al., 2008), ω-conotoxin GVIA (GVIA, 200 nM) to block N-type current (Randall and Tsien, 1995; McCallum et al., 2011), ω-conotoxin MVIIC (MVIIC, 200 nM) to block both N- and P/Q-type current (Randall and Tsien, 1995; McCallum et al., 2011), and 3,5-dichloro-N-[1-(2,2-dimethyltetrahudro-pyran-4-ylmethyl)-4-fluoropiperidin- 4-ylmethyl]-benzamide (TTA-P2; 1 μM; a kind gift from the Merck Research Laboratories, West Point, PA, USA), which is a potent and selective blocker of T-type current in rat sensory neurons (Choe et al., 2011). Stock solutions of TG, nimodipine, TTA-P2 and Fura-2-AM were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), and subsequently diluted in the relevant bath solution such that final bath concentration of DMSO was 0.2% or less, which does not effect [Ca2+]c (Avery and Johnston, 1997; Gemes et al., 2011). Other VGCC antagonist stock solutions were dissolved in water. The 500-μl recording chamber was superfused by gravity-driven flow at a rate of 3 ml/min. Agents were delivered by directed microperfusion controlled by a computerized valve system (ALA Scientific Instruments, Farmingdale, NY, USA) through a 500-μm diameter hollow quartz fiber 300-μm upstream from the neurons. This flow completely displaced the bath solution, and constant flow was maintained through this microperfusion pathway by delivery of bath solution when specific agents were not being administered. Dye imaging shows that solution changes were achieved within 200 ms.

Measurement of [Ca2+]c

Neurons plated on cover slips were exposed to Fura-2-AM (5 μM) for 30 min at room temperature in a solution that contained 2% bovine albumin to aid dispersion of the fluorophore, washed 3 times with regular Tyrode’s solution, and given 30 min for de-esterification. Neurons showing signs of lysis, crenulation or superimposed glial cells under brightfield illumination were excluded. For Ca2+ recording, the fluorophore was excited alternately with 340 and 380 nm wavelength illumination (150W Xenon, Lambda DG-4, Sutter, Novato, CA, USA), and images were acquired at 510 nm using a cooled 12-bit digital camera (Coolsnap fx, Photometrics, Tucson, AZ, USA) and inverted microscope (Diaphot 200, Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY, USA) through a 20× objective. Recordings from each neuron were obtained as separate regions (MetaFluor, Molecular Devices, Downingtown, PA, USA) at a rate of 1 Hz. After background subtraction, the fluorescence ratio R for individual neurons was determined as the intensity of emission during 340 nm excitation (I340) divided by I380, on a pixel-by-pixel basis. The Ca2+ concentration was then estimated by the formula Kd·β·(R − Rmin)/(Rmax − R) where β = (I380max)/(I380min). Values of Rmin, Rmax and β were determined by in situ calibration (Fuchs et al., 2005; Gemes et al., 2011) and were 0.38, 8.49 and 9.54, and Kd was 224 nm (Grynkiewicz et al., 1985). Only neurons with stable baseline R traces were further evaluated. Traces were analyzed using Axograph X 1.1 (Axograph Scientific, Sydney, Australia). Sensory neuron somatic diameter is broadly associated with specific sensory modalities (Ma et al., 2003). We therefore stratified neurons as large (diameter>34 μm), which represent predominantly fast conducting non-nociceptive neurons, or small (diameter ≤ 34 μm), which represent predominantly nociceptive neurons.

The change of resting [Ca2+]c was calculated as the difference between baseline and 2 min after bath solution change. Unless otherwise stated, small neurons were examined. Transients were generated by depolarization produced by microperfusion application of 50 mM K+ with 2 mM Ca2+ for 0.3 s or 35 mM K+ with 0.25 mM Ca2+ for 1 s, as specified below. These parameters were determined in preliminary studies to generate transient amplitudes less than 400 nM in most cases, thereby limiting involvement of mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering (Pottorf and Thayer, 2002; Usachev et al., 2006). Unless otherwise noted, neurons were depolarized only once, in order to avoid affecting SERCA function that might follow prior Ca2+ influx. Transients were fit well by a mono-exponential curve (Fig. 1), from which the time constant (τ) was derived as a measure of the pace of recovery.

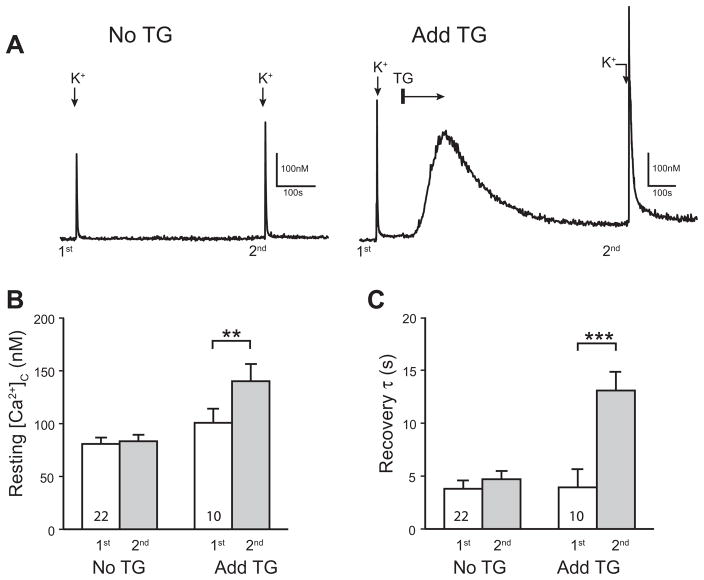

Fig. 1.

Sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) regulates resting and activity-induced cytoplasmic Ca2+ ([Ca2+]c) recovery in sensory neurons. Sample traces (A) showed that blocking SERCA by adding thapsigargin (1 μM; TG) to the bath solution (2 mM Ca2+) temporarily elevated resting [Ca2+]c, which did not return completely to its baseline after 8 min, whereas no such changes occurred in time controls (No TG). Summary data (B) document a significant increase of resting [Ca2+]c following TG administration. Also, K+-induced transients (50 mM for 0.3 s) recovered more slowly after TG administration (C). Mean±SEM; number in bars represents sample size; ***p<0.001.

Statistical analysis

Prism (version 4.1, GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) was used to perform paired or unpaired Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for testing the influence of injury or TG on measured parameters. Where main effects were observed in ANOVA, either Dunnett’s post hoc test (for comparison to a common reference group) or Tukey’s test (for comparisons between all groups) was used to compare relevant means, and a p value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Data are reported as mean±SEM.

RESULTS

The frequency of hyperalgesia responses after noxious punctate mechanical stimulation in SNL rats (40±4%, n=27) was greater than in control rats (0±0%, n=35; p<0.001). The accuracy of the SNL surgery was confirmed at the time of tissue harvest in all SNL animals.

SERCA operates in sensory neurons

Prior to characterizing the role of SERCA in normal and injured neurons, we first evaluated whether SERCA is active in control neurons at rest. We used TG to block SERCA function (Verkhratsky, 2005) in order to test whether SERCA operated constitutively in resting neurons. Consistent with prior observations (Wanaverbecq et al., 2003; Rigaud et al., 2009), blocking SERCA with TG (1 μM) produced a transient increase of [Ca2+]c due to the constitutive Ca2+ leak from intracellular stores (Fig. 1A). Upon recovery after TG, the resting [Ca2+]c was elevated compared to pre-TG baseline, whereas resting [Ca2+]c was unchanged by a similar time interval (Fig. 1A, B). This finding is in line with previous observations in other peripheral neurons (Wanaverbecq et al., 2003) and indicates constitutive operation of SERCA that indirectly regulates [Ca2+]c in resting sensory neurons. During neuronal activation by high bath K+, SERCA blockade caused prolongation of the Ca2+ transient compared to each neuron’s prior transient in TG-free bath (Fig. 1C), similar to prior observations of SERCA blockade in peripheral sensory neurons (Lu et al., 2006; Gover et al., 2007a). Time controls in the absence of TG showed no change of τ during repeat depolarization (Fig. 1C). An alternate SERCA blocker cyclopiazonic acid (Usachev et al., 2006) also prolonged τ (baseline 7.9±1.0 s, post-cyclopiazonic acid 12.8±1.2, p<0.01, n=8). These findings reveal the participation of SERCA in regulating both resting [Ca2+]c and Ca2+ signaling after neuronal activation. However, the simultaneous operation of other clearance mechanisms precludes the use of this approach for the measurement of the specific activity of SERCA per se under different injury conditions. We therefore employed the strategy of measuring SERCA selectively after eliminating the function of other relevant Ca2+ efflux pathways (Benham et al., 1992; Usachev et al., 2002).

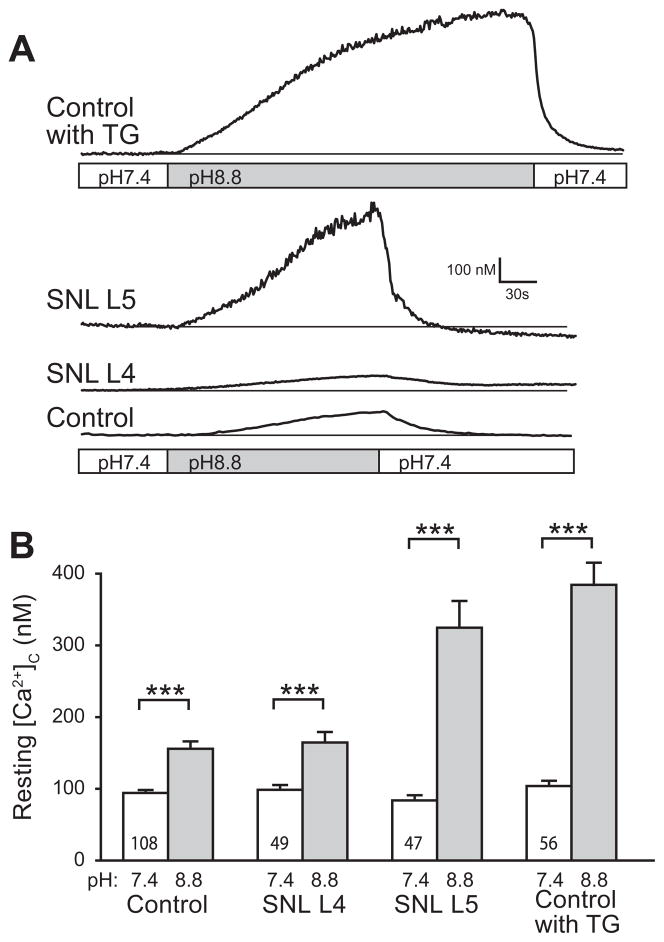

Isolation of SERCA function

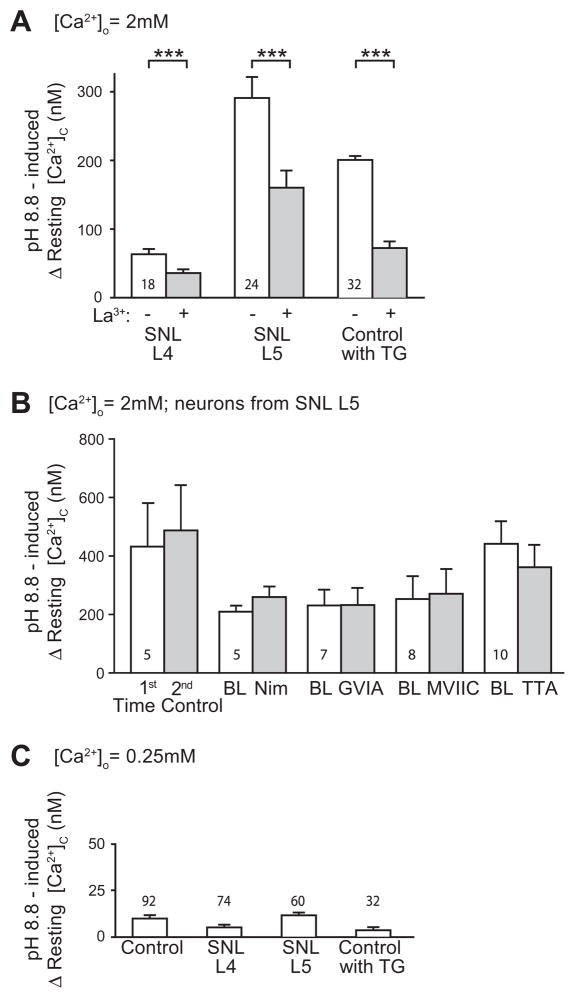

PMCA is the dominant pathway for extruding Ca2+ from the cytoplasm of sensory neurons (Usachev et al., 2002). This pump requires exchange of external H+ ions in order to extrude Ca2+ from the neuron, and therefore can be blocked by alkaline bath conditions (Benham et al., 1992; Duman et al., 2008). In sensory neurons from sham surgery animals, raising the pH to 8.8 resulted in a gradual and minor increase of resting [Ca2+]c consistent with the role of PMCA in balancing constitutive Ca2+ entry through SOCCs (Wanaverbecq et al., 2003; Gemes et al., 2011) (Fig. 2A, B). However, a substantial [Ca2+]c increase was noted in SNL L5 neurons upon exposure to pH 8.8 (Fig. 2A, B), which did not stabilize and reached levels that precluded meaningful measurement of activity-induced transient recovery. These changes were clearly distinct since baseline levels of [Ca2+]c were stable in the absence of a pH change. Removal of PMCA blockade by returning bath solution pH back to 7.4 resulted in prompt recovery of resting [Ca2+]c back to baseline (Fig. 2A), indicating that the effect is reversible, and that neurons are uninjured and PMCA remains functional. These findings indicated that PMCA assists SERCA in regulating resting [Ca2+]c in sensory neurons. To confirm that Ca2+ accumulation during PMCA blockade was due to unopposed Ca2+ influx through SOCCs, we limited SOCC function with bath-applied La3+ (5 μM) (Gemes et al., 2011). This diminished the increase of [Ca2+]c during application of pH 8.8 in SNL L4 and SNL L5 neurons (Fig. 3A), suggesting SOCCs as the main source of this Ca2+ influx. Although the effect of La3+ was incomplete, we have previously demonstrated that even higher doses of La3+ only partially block directly-measured SOCC currents (Gemes et al., 2011). Since La3+ may block VGCCs (Wakamori et al., 1998), we tested whether blocking these pathways of Ca2+ influx might replicate the ability of La3+ to block [Ca2+]c elevation when PMCA is inhibited. However, the response of SNL L5 neurons to pH 8.8 was unchanged by the administration of VGCC blockers (Fig. 3B). These observations support the view that there is minimal Ca2+ entry through VGCCs in a non-depolarized neuron, and that this is not the route of Ca2+ influx during PMCA blockade. It is possible that amplified Ca2+ entry through SOCC after nerve injury (Gemes et al., 2011) and defective SERCA function may cause axotomized SNL L5 neurons to be prone to cytoplasmic Ca2+ accumulation during PMCA blockade. We duplicated these conditions pharmacologically by exposing control neurons to TG, which directly blocks SERCA and indirectly activates SOCCs by depleting ER Ca2+ stores (Gemes et al., 2011). PMCA blockade by pH 8.8 during TG application reproduced the marked Ca2+ accumulation seen in SNL L5 neurons (Fig. 2A, B), and was also blocked by La3+ (Fig. 3A). Since our goal was to optimize recording conditions for gauging SERCA function, we minimized Ca2+ influx through SOCCs by decreasing bath Ca2+ concentration to 0.25 mM (Gemes et al., 2011). This substantially limited the [Ca2+]c elevation during application of pH 8.8 bath solution in neurons from control and injured animals (Fig. 3C) to a level suitable for exploration of SERCA function.

Fig. 2.

Blocking plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA) produced unstable cytoplasmic Ca2+ ([Ca2+]c) in injured sensory neurons. Eliminating PMCA function by changing bath pH from 7.4 to 8.8 (A) increased [Ca2+]c particularly in axotomized L5 neurons after spinal nerve ligation (SNL) and in Control neurons after thapsigargin treatment (1 μM; TG). [Ca2+]c returned to baseline after returning bath pH to 7.4. Summary data of [Ca2+]c (B) were obtained at baseline (pH 7.4) and after a fixed interval of 2 min following initiating pH 8.8 bath conditions, since a steady state level was not achieved. Significant increases were identified in all groups (paired t-test, ***p<0.001). Analysis of the incremental increases (ANOVA, p<0.001) showed that blocking PMCA increased [Ca2+]c more in the SNL L5 and Control with TG groups compared to Control. Mean±SEM; number in bars represents the sample size.

Fig. 3.

Increase of resting cytoplasmic Ca2+ ([Ca2+]c) during plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA) blockade. (A) In bath with 2 mM Ca2+([Ca2+]o=2 mM), the increase of [Ca2+]c during bath change from pH 7.4 to 8.8 for 2 min was greater under baseline conditions (“−”) than when repeated in the same neurons with La3+ (5 μM) in the bath (“+”). Neurons were obtained from rats after spinal nerve ligation (SNL) from the axotomized L5 ganglion and the neighboring L4 ganglion, as well as TG-treated control neurons. Mean±SEM; ***p<0.001. (B) In SNL L5 neurons, the increase of [Ca2+]c during bath change from pH 7.4 to 8.8 for 2 min was not significantly affected by blockers of VGCC subtypes L (5 μM nimodipine, “Nim”), N (200 nM ω-conotoxin GVIA “GVIA”), both N and P/Q (200 nM ω-conotoxin MVIIC, “MVIIC”), and T (1 μM 3,5-dichloro-N-[1-(2,2- dimethyltetrahudro-pyran-4-ylmethyl)-4-fluoro-piperidin-4-ylmethyl]-benzamide, TTA-P2, “TTA”). Bath change was performed at baseline (“BL”) and then repeated with the same neuron in the presence of the blocker. As a time control, bath change without blocker was performed at baseline (“1st”) and repeated (“2nd”). (C) Elevation of [Ca2+]c during bath change from pH 7.4 to 8.8 was greatly reduced in bath with low Ca2+ ([Ca2+]o=0.25 mM). Notice the different scale compared to panel A. Mean±SEM; number within or above the bars represents sample size.

Prior observations have shown that transients with amplitudes less than 400 nM are insufficient to initiate mitochondrial buffering (Benham et al., 1992; Werth and Thayer, 1994; Pottorf and Thayer, 2002; Usachev et al., 2002). Accordingly, we activated neurons by depolarization with a K+ concentration (35 mM) and duration (1 s) that triggered transients within this limit. We additionally restricted the contribution of mitochondrial buffering by excluding measurements from traces that showed a shoulder or plateau of sustained Ca2+ elevation during the descending limb of the activity-induced transient, since this pattern represents the participation of mitochondrial buffering (Friel and Tsien, 1992). These criteria additionally exclude any substantial contribution by the NCX in sensory neurons (Benham et al., 1992; Gover et al., 2007b). We have confirmed that in sensory neurons there is no measurable contribution by mitochondria and NCX to the resolution of activity-induced transients comparable to those evaluated in this report, using sensory neurons from comparable animals (Gemes et al., 2012). A further factor that can influence the pace of transient recovery is the simultaneous release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores through the process of Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) (Albrecht et al., 2001; Hongpaisan et al., 2001). However, since small [Ca2+]c elevations stimulate Ca2+ uptake more effectively than Ca2+ release (Albrecht et al., 2002), interference in SERCA measurement by CICR activity can also be limited by constraining the amplitude of Ca2+ transients (Albrecht et al., 2001, 2002). Together, these criteria resulted in exclusion of 32% of transients from evaluation.

We have previously demonstrated that injury reduces transient amplitude in SNL L5 neurons (Fuchs et al., 2007). In our present data, transient amplitude is similarly depressed in SNL L5 neurons under our present conditions of PMCA blockade (Fig. 4A, B), indicating that this feature of injury is not due solely to altered PMCA function. Injury also affected neuronal size, with a decreased average diameter in axotomized SNL L5 neurons (27.0±0.4 μm, n=216) compared to Control (29.1±0.2 μm, n=430; p<0.001 vs. SNL L5), consistent with our prior findings (Sapunar et al., 2005), whereas the diameter was increased in neighboring SNL L4 neurons (31.2±0.4 μm, n=178; p<0.001 vs. Control).

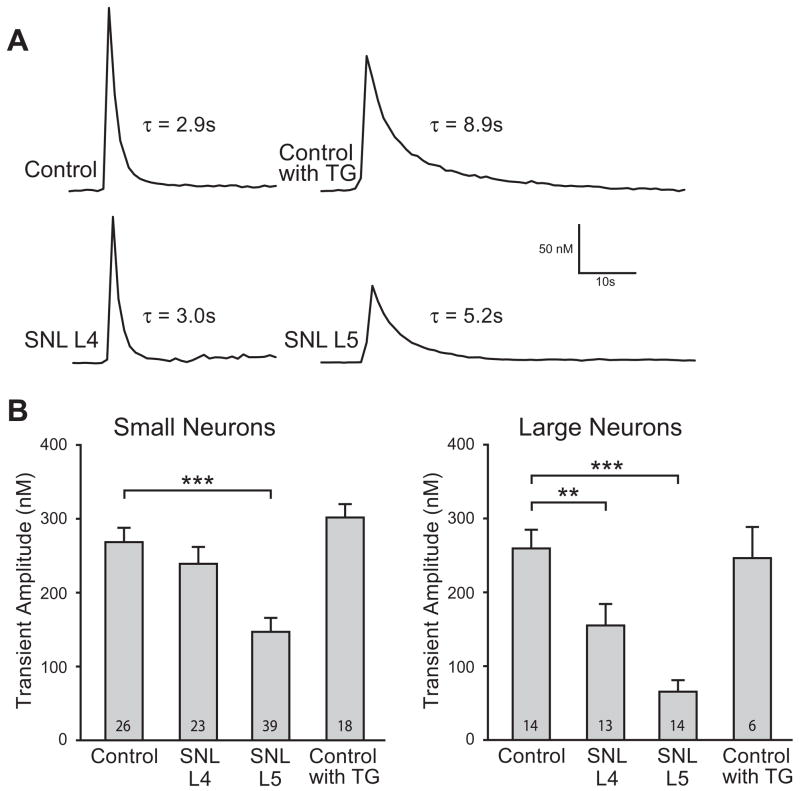

Fig. 4.

Injury reduced the amplitude of the Ca2+ transient induced by neuronal activation during plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA) blockade. Sample traces (A) showed smaller K+-induced transient amplitude in small (≤34 μm) spinal nerve ligation (SNL) L5 neurons during PMCA blockade (pH 8.8) in low Ca2+ (0.25 mM) external bath. Traces also demonstrate delayed transient recovery in SNL L5 neurons and thapsigargin-treated (TG, 1 μM) Control neurons, measured as the time constant for exponential fit (τ). Summary data (B) demonstrate a significantly diminished K+-induced transient amplitude in both large (>34 μm) and small SNL L5 neurons but not in TG-treated Control neurons during PMCA blockade. Mean±SEM; number in bars represents the sample size; **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Axotomy reduces SERCA function in small neurons

By isolating SERCA as described above, we measured the rate of recovery from activity-induced Ca2+ transients as an index of SERCA activity. In small neurons, this showed diminished SERCA function in after axotomy (SNL L5) compared to Control, and no effect on neighboring SNL L4 neurons (Fig. 5A). As a positive control for our approach, we examined recovery of transients following TG treatment in addition to bath pH 8.8. TG resulted in substantial prolongation of recovery in Control neurons (Figs. 4A, 5A), although recovery eventually was achieved, indicating Ca2+ removal from the cytoplasm by persisting low capacity mechanisms such as SPCA. In SNL L5 neurons, the prolongation of transient recovery by TG was less than the effect of TG on Control and SNL L4 neurons (Fig. 5A), indicating diminished remaining SERCA function in the SNL L5 group. TG treatment eliminated differences in transient recovery between control and injury groups, indicating that the effect of injury on τ was due to altered SERCA function, and that residual (non-SERCA) Ca2+ handling processes were not affected by injury.

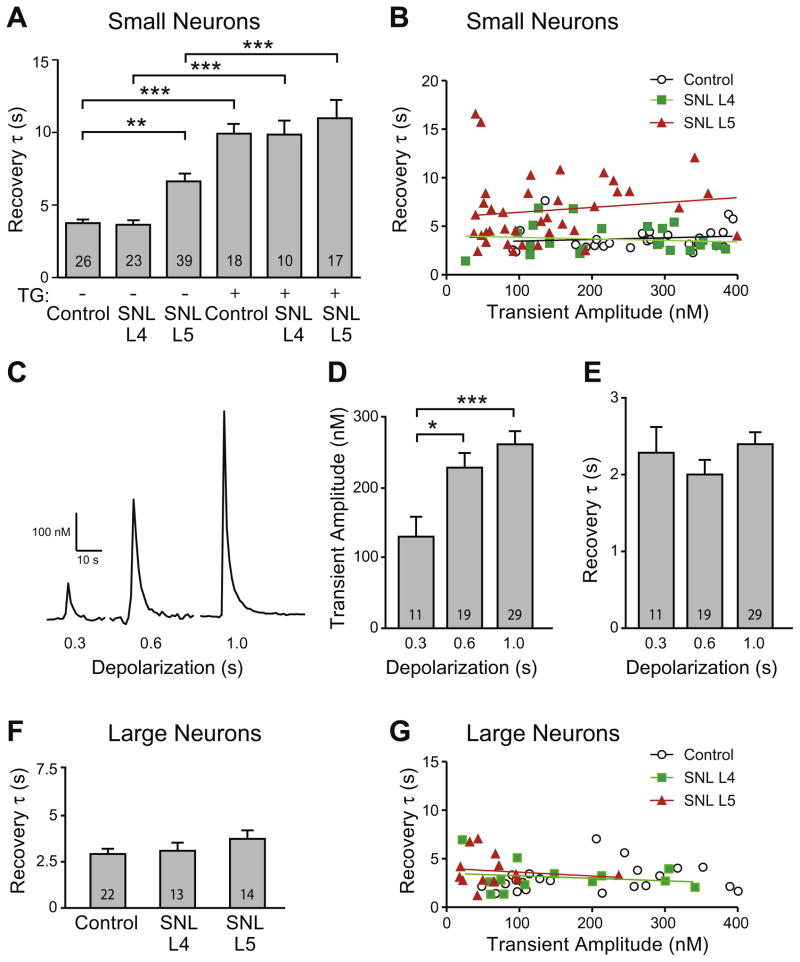

Fig. 5.

Injury prolonged recovery of activity-induced (K+, 35 mM, 1 s) transients recorded after plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA) blockade in low bath Ca2+ (0.25 mM) represented by the time constant for exponential fit (τ). (A) Summary data for small neurons (≤34 μm) from Control and spinal nerve ligation (SNL) animals, either with or without thapsigargin (TG, 1 μM) shows prolonged recovery of transients after axotomy (SNL L5 neurons), but no influence of injury in TG-treated neurons. Post hoc paired comparisons were evaluated between injury groups and their respective (with or without TG) control, and for each injury category between absence and presence of TG (e.g. SNL L4 with TG vs. SNL L4 without TG). (B) Transient recovery was not affected by transient amplitude in small Control, SNL L4 and SNL L5 neurons (regression p of 0.53, 0.59 and 0.38 for Control, SNL L4, and SNL L5, respectively; R2 of 0.017, 0.014 and 0.021 for Control, SNL L4, SNL L5, respectively). Sample traces (C) showed that increased Ca2+ influx during longer K+-depolarizations induced larger transient amplitude but did not affect transient recovery (τ) in small Control neurons. Summary data demonstrate increasing Ca2+ influx with depolarization duration (D) but unaffected τ (E). In large neurons (F), recovery was not different in SNL L4 and SNL L5 neurons compared to Control. Rate of recovery in large neurons (G) was also unaffected by transient amplitude (regression p of 0.40, 0.55 and 0.66 for Control, SNL L4 and SNL L5, respectively; R2 of 0.035, 0.033 and 0.017 for Control, L4, L5, respectively. Mean±SEM; number in bars represents the sample size; *p<0.05, ***p<0.001.

Because SNL L5 neurons have smaller transient amplitudes compared to controls (Fig. 4B), we considered whether reduced cytoplasmic Ca2+ accumulation may itself affect SERCA function (Albrecht et al., 2002). Regression analysis showed no influence of transient amplitude upon τ in Control, SNL L4, or SNL L5 small neurons (Fig. 5B). We also compared transient recovery in a restricted population of these neurons that had comparable transient amplitudes (90–220 nM). These still showed a significant slowing of recovery in SNL L5 neurons (average amplitude of 145±10 nM, τ of 6.0±0.7 s, n=16) compared to Control (158±17 nM, 3.6±0.5 s, n=9; p<0.05 for τ), whereas SNL L4 (148±12 nM, 4.1±0.6 s, n=10) was not different from Control. Finally, we directly examined the possibility that Ca2+ load may regulate SERCA function using an experimental design in which duration of membrane depolarization was varied. This successfully produced scaled Ca2+ influx (Fig. 5C, D), but did not affect transient recovery kinetics (Fig. 5E). These findings support an effect of injury on SERCA independent of the level of Ca2+ influx in small sensory neurons.

In the large neuron category, however, transient recovery in SNL L4 and L5 neurons was unaffected compared to Control (Fig. 5F). Regression analysis in this population also showed that transient amplitude did not affect τ (Fig. 5G).

Influence of prior neuronal activation on SERCA

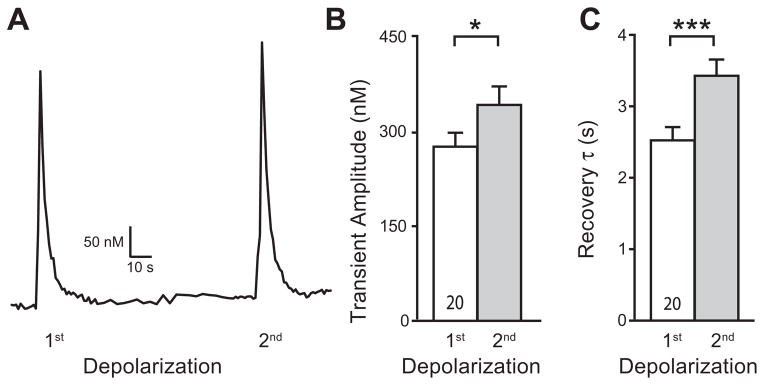

The level of activity in injured neurons may be substantially altered following injury due to either disconnection from receptive field stimulation or to new ectopic activity (Gold, 2000; Zimmermann, 2001; Hogan, 2007). To investigate this influence, we exposed neurons to repeated Ca2+ loads similar to those triggered by trains of APs in intact DRGs (Gemes et al., 2010). Control sensory neurons received a K+ depolarization that was repeated after 2 min (Fig. 6A). Prior activation resulted in an increased amplitude and slower transient recovery.

Fig. 6.

Repeated neuronal activation leads to slowed transient recovery (τ) in neurons with blocked plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA). Sample trace (A) showed a higher transient amplitude and slower τ after repeated K+-depolarization in a control neuron. Summary data show that increased transient amplitude (B) and prolonged τ (C) in the 2nd K+-induced transient (35 mM, 1 s) in low Ca2+ (0.25 mM) external bath of small (≤34 μm) Control neurons. Mean±SEM; number in bars represents the sample size; ***p<0.001.

DISCUSSION

Several findings emerge from our examination of SERCA function in control and injured sensory neurons. SERCA operates constitutively in these neurons even while they are inactive and participates in the regulation of resting [Ca2+]c. Upon neuronal activation, SERCA contributes to recovery of the Ca2+ transient. When PMCA function is eliminated, SERCA aids in buffering unopposed Ca2+ influx. The particular susceptibility of axotomized L5 neurons to [Ca2+]c elevation after PMCA block in resting neurons is due to a loss of SERCA function. This injury-induced deficit in SERCA Ca2+ transport capacity is particularly evident in delayed recovery of Ca2+ transients selectively in small SNL L5 neurons after activation.

Dynamic interactions modulate the Ca2+ clearance pathways to counterbalance the Ca2+ influx after cellular excitation (Brini and Carafoli, 2009). In order to isolate SERCA function, we devised a technique that eliminates PMCA, minimizes mitochondrial buffering, and reduces Ca2+ accumulation from influx through SOCCs. We did not block a possible contaminating factor of CICR, which is a process present in sensory neurons by which Ca2+ influx into the cytoplasm triggers release of stored Ca2+ (Gemes et al., 2009). Although Ca2+ released into the cytoplasm by CICR could conceivably delay recovery of [Ca2+]c after neuronal activation, CICR is reduced in SNL L5 neurons (Gemes et al., 2009), so our findings may underestimate the extent by which SERCA function is slowed following injury.

Our present findings regarding SERCA allow some comparisons to be made with the function of sensory neuron PMCA, which we explored in a related investigation (Gemes et al., 2012). Blockade of SERCA in control neurons resets the balance of PMCA and SOCC that controls [Ca2+]c but neurons remain stable thereafter. However, blockade of PMCA results in instability of the [Ca2+]c, which indicates that SERCA function alone lacks the capacity to accommodate continuing Ca2+ influx. Regarding the resolution of low-amplitude transients that follow neuronal activation, selective removal of PMCA in otherwise untreated control neurons increases τ approximately 1.9-fold (Fig. 1C) (Gemes et al., 2012), whereas exclusion of SERCA function under similar conditions increases τ approximately 3.7-fold (Fig. 1C, present report). This difference may be due to a relatively smaller contribution of PMCA to clearance of Ca2+ from the cytoplasm under control conditions. Alternatively, SERCA may be able to upregulate its functional level when PMCA is blocked, whereas PMCA may posses only a relatively limited range of compensatory increase upon loss of SERCA. Our findings of a τ of approximately 4 s when isolated SERCA alone accounts for transient recovery in control cells (Fig. 5A) but a τ of approximately 17 s when isolated PMCA performs this function (Gemes et al., 2012) suggests a greater pumping capacity for SERCA.

Sensory neurons are a diverse population with various functional and molecular attributes. Whereas small unmyelinated neurons generally carry nociceptive traffic, large myelinated neurons are activated by low threshold stimuli (Ma et al., 2003). Our present findings show that injury has distinct effects on SERCA function in these two populations. Specifically, injured small diameter neurons from L5 after SNL showed diminished SERCA function compared to controls, while no significant difference was found in injured large neurons. We considered two possible causal factors. Since SERCA function is sensitive to the level of [Ca2+]c (Wanaverbecq et al., 2003), it is possible that the loss of transient amplitude after injury account for diminished SERCA activity. However, we found that injury slowed SERCA function independent of transient amplitude, and altering the size of the transient in control neurons did not affect the pace of transient recovery. Also, we have previously observed that Ca2+ stores cannot be expanded in injured neurons by inducing a substantial Ca2+ influx, so it is unlikely that unavailability of adequate cytoplasmic Ca2+ contributes to injury-induced SERCA dysfunction.

We also examined whether the activity history of the neuron may affect SERCA function, which revealed slower transient recovery after prior activity. Since mitochondrial sequestration and the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger contribute minimally to transient recovery in our prior findings with a similar preparation (Gemes et al., 2012), the present observations point to diminished SERCA function following neuronal activity. This may reflect progressive saturation of the ER storage capacity, and suggests that injured neurons have developed a similar state of maximized ER Ca2+ storage. Our prior studies offer some insights into possible underlying causes. Depletion of ATP is an unlikely explanation since PMCA function is maintained as an accelerated level after injury (Gemes et al., 2012). Morphometric analysis shows loss of ER profiles (Gemes et al., 2009), so the dimensions of the storage compartment may be a limiting factor. Related to this, our immunohistochemical evidence points to a loss of TG binding sites, suggesting total SERCA units are likewise depleted (Gemes et al., 2009). Other evidence, however, points also to a deficiency in SERCA function per se. Specifically, microfluorimetric measurement of Ca2+ in the ER lumen shows decreased free [Ca2+]L in sensory neurons following injury (Rigaud et al., 2009). Since Ca2+ binding proteins in the ER lumen activate SERCA to maintain [Ca2+]L (John et al., 1998; Li and Camacho, 2004), our observation of low [Ca2+]L suggests altered SERCA function, although deficient number of SERCA units may contribute to low [Ca2+]L. SERCA and proteins that regulate its function are targets of the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) (Wuytack et al., 2002), and we have previously identified loss of CaMKII signaling in injured sensory neurons (Kawano et al., 2009; Kojundzic et al., 2010), so this regulatory pathway may be involved in SERCA loss with injury. However, block of this kinase had no effect on SERCA function of control neurons measured in the fashion described above (data not shown).

Diminished SERCA function in injured sensory neurons may potentially have diverse physiological consequences. SERCA combines with PMCA to provide recovery of [Ca2+]c following neuronal activation. We have previously found that injury results in more rapid recovery of Ca2+ transients (Fuchs et al., 2007), which predicts that the slowed SERCA we have found in the present study is not a dominant factor in transient recovery. Consistent with this, we have also recently shown accelerated PMCA function after injury (Gemes et al., 2012). A more critical sequela of SERCA loss after injury may be depressed Ca2+ stores. This may produce diminished CICR and neuronal hyperexcitability (Gemes et al., 2009). Furthermore, disruption of [Ca2+]L leads to ER stress, altered protein production, and neurodegeneration (Paschen, 2001; Verkhratsky, 2005). Thus, SERCA dysfunction may contribute to the long-term consequences of nerve damage and maintenance of chronic pain.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant NS-42150 (to Q.H.H.) and DA-K01-024751 (to H.-E.W.). V.N.U. and J.J.R. are employees of Merck and Co., Inc. and may own stock and/or stock options in the company.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- [Ca2+]c

cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration

- [Ca2+]L

endoplasmic reticulum lumen Ca2+ concentration

- CICR

Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DRG

dorsal root ganglion

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- HEPES

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid

- L4

fourth lumbar

- L5

fifth lumbar

- NCX

Na+/Ca2+ exchanger

- PMCA

plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase

- SERCA

sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase

- SNL

spinal nerve ligation

- SOCC

store-operated Ca2+ channel

- SPCA

secretory pathway Ca2+/Mn2+-ATPases

- TG

thapsigargin

- TTA-P2

3,5-dichloro-N-[1-(2,2-dimethyltetrahudropyran-4-ylmethyl)-4-fluoro-piperidin-4-ylmethyl]-benzamide

- VGCC

voltage-gated Ca2+ channel

References

- Albrecht MA, Colegrove SL, Friel DD. Differential regulation of ER Ca2+ uptake and release rates accounts for multiple modes of Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release. J Gen Physiol. 2002;119:211–233. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht MA, Colegrove SL, Hongpaisan J, Pivovarova NB, Andrews SB, Friel DD. Multiple modes of calcium-induced calcium release in sympathetic neurons: I. Attenuation of endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ accumulation at low [Ca2+](i) during weak depolarization. J Gen Physiol. 2001;118:83–100. doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avery RB, Johnston D. Ca2+ channel antagonist U-92032 inhibits both T-type Ca2+ channels and Na+ channels in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1997;77:1023–1028. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.2.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benham CD, Evans ML, McBain CJ. Ca2+ efflux mechanisms following depolarization evoked calcium transients in cultured rat sensory neurones. J Physiol. 1992;455:567–583. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brini M, Carafoli E. Calcium pumps in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:1341–1378. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00032.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camello C, Lomax R, Petersen OH, Tepikin AV. Calcium leak from intracellular stores – the enigma of calcium signalling. Cell Calcium. 2002;32:355–361. doi: 10.1016/s0143416002001926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe W, Messinger RB, Leach E, Eckle VS, Obradovic A, Salajegheh R, Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Todorovic SM. TTA-P2 is a potent and selective blocker of T-type calcium channels in rat sensory neurons and a novel antinociceptive agent. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;80:900–910. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.073205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman JG, Chen L, Hille B. Calcium transport mechanisms of PC12 cells. J Gen Physiol. 2008;131:307–323. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes AM, Landeira-Fernandez AM, Souza-Santos P, Carvalho-Alves PC, Castilho RF. Quinolinate-induced rat striatal excitotoxicity impairs endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase function. Neurochem Res. 2008;33:1749–1758. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9619-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernyhough P, Calcutt NA. Abnormal calcium homeostasis in peripheral neuropathies. Cell Calcium. 2010;47:130–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierro L, DiPolo R, Llano I. Intracellular calcium clearance in Purkinje cell somata from rat cerebellar slices. J Physiol. 1998;510(Pt. 2):499–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.499bk.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friel DD, Tsien RW. A caffeine- and ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ store in bullfrog sympathetic neurones modulates effects of Ca2+ entry on [Ca2+]i. J Physiol. 1992;450:217–246. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs A, Lirk P, Stucky C, Abram SE, Hogan QH. Painful nerve injury decreases resting cytosolic calcium concentrations in sensory neurons of rats. Anesthesiology. 2005;102:1217–1225. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200506000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs A, Rigaud M, Hogan QH. Painful nerve injury shortens the intracellular Ca2+ signal in axotomized sensory neurons of rats. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:106–116. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000267538.72900.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego-Sandin S, Alonso MT, Garcia-Sancho J. Calcium homoeostasis modulator 1 (CALHM1) reduces the calcium content of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and triggers ER stress. Biochem J. 2011;437:469–475. doi: 10.1042/BJ20110479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemes G, Bangaru ML, Wu HE, Tang Q, Weihrauch D, Koopmeiners AS, Cruikshank JM, Kwok WM, Hogan QH. Store-operated Ca2+ entry in sensory neurons: functional role and the effect of painful nerve injury. J Neurosci. 2011;31:3536–3549. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5053-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemes G, Oyster KD, Pan B, Wu HE, Bangaru ML, Tang Q, Hogan QH. Painful nerve injury increases plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase activity in axotomized sensory neurons. Mol Pain. 2012;8:46. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-8-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemes G, Rigaud M, Koopmeiners AS, Poroli MJ, Zoga V, Hogan QH. Calcium signaling in intact dorsal root ganglia: new observations and the effect of injury. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:134–146. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181e0ef3f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gemes G, Rigaud M, Weyker PD, Abram SE, Weihrauch D, Poroli M, Zoga V, Hogan QH. Depletion of calcium stores in injured sensory neurons: anatomic and functional correlates. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:393–405. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181ae63b0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Greenberg ME. Calcium signaling in neurons: molecular mechanisms and cellular consequences. Science. 1995;268:239–247. doi: 10.1126/science.7716515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleichmann M, Mattson MP. Neuronal calcium homeostasis and dysregulation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:1261–1273. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold MS. Spinal nerve ligation: what to blame for the pain and why. Pain. 2000;84:117–120. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00309-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gover TD, Moreira TH, Kao JP, Weinreich D. Calcium homeostasis in trigeminal ganglion cell bodies. Cell Calcium. 2007a;41:389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gover TD, Moreira TH, Kao JP, Weinreich D. Calcium regulation in individual peripheral sensory nerve terminals of the rat. J Physiol. 2007b;578:481–490. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.119008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerini D, Coletto L, Carafoli E. Exporting calcium from cells. Cell Calcium. 2005;38:281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich M, Buckler KJ. Effects of anoxia and aglycemia on cytosolic calcium regulation in rat sensory neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2008;100:456–473. doi: 10.1152/jn.01380.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan Q, Sapunar D, Modric-Jednacak K, McCallum JB. Detection of neuropathic pain in a rat model of peripheral nerve injury. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:476–487. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200408000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan QH. Role of decreased sensory neuron membrane calcium currents in the genesis of neuropathic pain. Croat Med J. 2007;48:9–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hongpaisan J, Pivovarova NB, Colegrove SL, Leapman RD, Friel DD, Andrews SB. Multiple modes of calcium-induced calcium release in sympathetic neurons: II. A [Ca2+](i)- and location-dependent transition from endoplasmic reticulum Ca accumulation to net Ca release. J Gen Physiol. 2001;118:101–112. doi: 10.1085/jgp.118.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John LM, Lechleiter JD, Camacho P. Differential modulation of SERCA2 isoforms by calreticulin. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:963–973. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.4.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawano T, Zoga V, Gemes G, McCallum JB, Wu HE, Pravdic D, Liang MY, Kwok WM, Hogan Q, Sarantopoulos C. Suppressed Ca2+/CaM/CaMKII-dependent K(ATP) channel activity in primary afferent neurons mediates hyperalgesia after axotomy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8725–8730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901815106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Chung JM. An experimental model for peripheral neuropathy produced by segmental spinal nerve ligation in the rat. Pain. 1992;50:355–363. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojundzic SL, Puljak L, Hogan Q, Sapunar D. Depression of Ca(2+)/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in dorsal root ganglion neurons after spinal nerve ligation. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518:64–74. doi: 10.1002/cne.22209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen GA, Skjellegrind HK, Moe MC, Vinje ML, Berg-Johnsen J. Endoplasmic reticulum dysfunction and Ca2+ deregulation in isolated CA1 neurons during oxygen and glucose deprivation. Neurochem Res. 2005;30:651–659. doi: 10.1007/s11064-005-2753-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Camacho P. Ca2+-dependent redox modulation of SERCA 2b by ERp57. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:35–46. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu SG, Zhang X, Gold MS. Intracellular calcium regulation among subpopulations of rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Physiol. 2006;577:169–190. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.116418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytton J. Na+/Ca2+ exchangers: three mammalian gene families control Ca2+ transport. Biochem J. 2007;406:365–382. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C, Shu Y, Zheng Z, Chen Y, Yao H, Greenquist KW, White FA, LaMotte RH. Similar electrophysiological changes in axotomized and neighboring intact dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:1588–1602. doi: 10.1152/jn.00855.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata AM, Sepulveda MR. Calcium pumps in the central nervous system. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;49:398–405. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCallum JB, Wu HE, Tang Q, Kwok WM, Hogan QH. Subtype-specific reduction of voltage-gated calcium current in medium-sized dorsal root ganglion neurons after painful peripheral nerve injury. Neuroscience. 2011;179:244–255. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.01.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mengesdorf T, Althausen S, Oberndorfer I, Paschen W. Response of neurons to an irreversible inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+)-ATPase: relationship between global protein synthesis and expression and translation of individual genes. Biochem J. 2001;356:805–812. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3560805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschen W. Dependence of vital cell function on endoplasmic reticulum calcium levels: implications for the mechanisms underlying neuronal cell injury in different pathological states. Cell Calcium. 2001;29:1–11. doi: 10.1054/ceca.2000.0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottorf WJ, Duckles SP, Buchholz JN. Adrenergic nerves compensate for a decline in calcium buffering during ageing. J Auton Pharmacol. 2000a;20:1–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2680.2000.00153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottorf WJ, Duckles SP, Buchholz JN. SERCA function declines with age in adrenergic nerves from the superior cervical ganglion. J Auton Pharmacol. 2000b;20:281–290. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2680.2000.00194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pottorf WJ, Thayer SA. Transient rise in intracellular calcium produces a long-lasting increase in plasma membrane calcium pump activity in rat sensory neurons. J Neurochem. 2002;83:1002–1008. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall A, Tsien RW. Pharmacological dissection of multiple types of Ca2+ channel currents in rat cerebellar granule neurons. J Neurosci. 1995;15:2995–3012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-04-02995.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigaud M, Gemes G, Weyker PD, Cruikshank JM, Kawano T, Wu HE, Hogan QH. Axotomy depletes intracellular calcium stores in primary sensory neurons. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:381–392. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181ae6212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapunar D, Ljubkovic M, Lirk P, McCallum JB, Hogan QH. Distinct membrane effects of spinal nerve ligation on injured and adjacent dorsal root ganglion neurons in rats. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:360–376. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200508000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sepulveda MR, Berrocal M, Marcos D, Wuytack F, Mata AM. Functional and immunocytochemical evidence for the expression and localization of the secretory pathway Ca2+-ATPase isoform 1 (SPCA1) in cerebellum relative to other Ca2+ pumps. J Neurochem. 2007;103:1009–1018. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutzmann GE, Mattson MP. Endoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) handling in excitable cells in health and disease. Pharmacol Rev. 2011;63:700–727. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki S, Osanai M, Mitsumoto N, Akita T, Narita K, Kijima H, Kuba K. Ca(2+)-dependent Ca(2+) clearance via mitochondrial uptake and plasmalemmal extrusion in frog motor nerve terminals. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:1816–1823. doi: 10.1152/jn.00456.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usachev YM, DeMarco SJ, Campbell C, Strehler EE, Thayer SA. Bradykinin and ATP accelerate Ca(2+) efflux from rat sensory neurons via protein kinase C and the plasma membrane Ca(2+) pump isoform 4. Neuron. 2002;33:113–122. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00557-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usachev YM, Marsh AJ, Johanns TM, Lemke MM, Thayer SA. Activation of protein kinase C in sensory neurons accelerates Ca2+ uptake into the endoplasmic reticulum. J Neurosci. 2006;26:311–318. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2920-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhratsky A. Endoplasmic reticulum calcium signaling in nerve cells. Biol Res. 2004;37:693–699. doi: 10.4067/s0716-97602004000400027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhratsky A. Physiology and pathophysiology of the calcium store in the endoplasmic reticulum of neurons. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:201–279. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00004.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakamori M, Strobeck M, Niidome T, Teramoto T, Imoto K, Mori Y. Functional characterization of ion permeation pathway in the N-type Ca2+ channel. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79:622–634. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.2.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanaverbecq N, Marsh SJ, Al-Qatari M, Brown DA. The plasma membrane calcium-ATPase as a major mechanism for intracellular calcium regulation in neurones from the rat superior cervical ganglion. J Physiol. 2003;550:83–101. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.035782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werth JL, Thayer SA. Mitochondria buffer physiological calcium loads in cultured rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurosci. 1994;14:348–356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-01-00348.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu HE, Gemes G, Zoga V, Kawano T, Hogan QH. Learned avoidance from noxious mechanical simulation but not threshold semmes weinstein filament stimulation after nerve injury in rats. J Pain. 2010;11:280–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu ZZ, Chen SR, Pan HL. Distinct inhibition of voltage-activated Ca2+ channels by delta-opioid agonists in dorsal root ganglion neurons devoid of functional T-type Ca2+ currents. Neuroscience. 2008;153:1256–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuytack F, Raeymaekers L, Missiaen L. Molecular physiology of the SERCA and SPCA pumps. Cell Calcium. 2002;32:279–305. doi: 10.1016/s0143416002001847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zherebitskaya E, Schapansky J, Akude E, Smith DR, Van der Ploeg R, Solovyova N, Verkhratsky A, Fernyhough P. Sensory neurons derived from diabetic rats have diminished internal Ca2+ stores linked to impaired re-uptake by the endoplasmic reticulum. ASN Neuro. 2012:4. doi: 10.1042/AN20110038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann M. Pathobiology of neuropathic pain. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;429:23–37. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01303-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]