Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the transfer of heterologous genes carrying a Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) reporter cassette to primary corneal epithelial cells ex vivo.

Methods

Freshly enucleated rabbit corneoscleral tissue was used to obtain corneal epithelial cell suspension via enzymatic digestion. Cells were plated at a density of 5×103 cells/cm2 and allowed to grow for 5 days (to 70–80% confluency) prior to transduction. Gene transfer was monitored using fluorescence microscopy and fluorescence activated cell sorter (FACS). We evaluated the transduction efficiency (TE) over time and the dose-response effect of different lentiviral particles. One set of cells were dual sorted by fluorescence activated cell sorter for green fluorescent protein expression as well as Hoechst dye exclusion to evaluate the transduction of potentially corneal epithelial stem cells (side-population phenotypic cells).

Results

Green fluorescent protein expressing lentiviral vectors were able to effectively transduce rabbit primary epithelial cells cultured ex vivo. Live cell imaging post-transduction demonstrated GFP-positive cells with normal epithelial cell morphology and growth. The transduction efficiency over time was higher at the 5th post-transduction day (14.1%) and tended to stabilize after the 8th day. The number of transduced cells was dose-dependent, and at the highest lentivirus concentrations approached 7%. When double sorted by fluorescence activated cell sorter to isolate both green fluorescent protein positive and side population cells, transduced side population cells were identified.

Conclusions

Lentiviral vectors can effectively transfer heterologous genes to primary corneal epithelial cells expanded ex vivo. Genes were stably expressed over time, transferred in a dose-dependence fashion, and could be transferred to mature corneal cells as well as presumable putative stem cells.

Keywords: Gene therapy, Corneal diseases, Lentivirus/genetics, Transgenes/genetics, Stem cells, Epithelium corneal/physiology, Gene expression

INTRODUCTION

Great progress has been made in molecular cell biology and genetics to understand the basic cellular mechanism and the potential for genetic therapy. Technological advances in that field, especially in recombinant DNA techniques, have enabled scientists to develop gene therapy techniques for the treatment of human diseases. It is an approach that offers potential to cure diseases or abnormal medical conditions by transferring new genetic material to target cells/tissue. Gene therapy has the advantage of modulating pathophysiological diseases at the molecular level, which offers the potential to cure them, or at least to promote long term therapeutical benefits, instead of transient benefits with conventional pharmacotherapy.

An efficient gene delivery system is essential to transfer genes to live cells and tissues. Vectors can be distinguished by their ability to integrate genetic material in the target cell genome. Gene transfer can be stable or transient according to the vectors’ ability to integrate the genetic material into the host genome or not(1–2).

Basically, gene delivery systems can be broadly classified in two categories: methods mediated by viral vectors and methods using non-viral vectors. Viral methods are capable of delivering genes at high efficiency for longer periods of time compared to the non-viral methods. Nevertheless, these methods may pose safety threats to patients and the environment. Genes can also be delivered using non-viral methods. These methods require plasmid vector for delivery of genes of interest into cells. Several methods have been developed, including mechanical, electrical, and chemical approaches. Synthetic DNA delivery systems are versatile and safe, but substantially less efficient in delivering genetic material than viral vectors. In general, these methods are non-toxic and non-pathogenic and do not trigger strong immune responses in the host. They still may be very useful for situations where only transient gene expression is required such as in corneal wound healing(1–2).

The cornea is an excellent candidate for gene therapy because of its accessibility and immune-privileged nature. Furthermore, the cornea epithelium can be maintained in standard culture conditions for extended periods of up to 1 month prior to transplantation, which allows opportunities for genetic modification prior to reintroduction into patients. The epithelial layer, which is renewed by corneal epithelial stem cells, plays a relevant role promoting protection and refractive properties essential for vision(3–7). As current techniques for reconstructing the ocular surface damaged by stem cell deficiency involve transplantation of expanded corneal epithelial cells ex vivo(8–9), the epithelial layer, including presumed limbal stem cells, becomes an attractive target for gene therapy to ocular surface diseases.

This study investigates the feasibility of transducing rabbit primary corneal epithelial cells as well as side population phenotypic corneal epithelial cells using a lentiviral vector carrying a green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter cassette ex vivo. We sought to evaluate the expression of transduced genes over time and the dose-response effect of lentiviral particles (cfu/mL) used for transduction.

METHODS

Preparation of rabbit limbal epithelial cell suspension

All investigations were carried out in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and with federal, state, and local regulations. New Zealand white rabbits were euthanized with an overdose of 50 mg/kg ketamine and 7.5 mg/kg xylasine intramuscularly and an additional air injection in the ear vein (5cc). Conjunctival peritomy was performed and the entire cornea was excised including a 1.0 mm scleral rim. Rabbit keratolimbal tissue was divided into quadrants and placed epithelium side down in 50mg/mL Dispase II solution (37°C and 5% CO2) for one hour. After chemical digestion, the limbal epithelial sheets were released from the explants using a sterile spatula with a blunt blade. The sheets were pelleted by centrifugation at 1000g for five minutes and after removal of the supernatant, they were incubated for 15 minutes at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a 0.25% trypsin and 0.1% EDTA 0.1% solution. Trypsin was neutralized and the cells resuspended in EpiLife® Medium (Cascade Biologics, Portland, OR) supplemented with 1% Human Keratinocyte Growth Supplement (Cascade Biologics, Portland, OR; containing 0.2% bovine pituitary extract + 5 μg/mL bovine insulin + 0.18 μg/mL hydrocortisone 0.18 + 5 μg/mL bovine transferrin + 0.2 ng/mL human epidermal growth factor), with 1% PSG + amphotericin B (penicillin G sodium 10000 μg/mL, streptomycin sulfate 25 μg/mL, amphotericin B in 0.85% saline - Gibco - Invitrogen Corporation), 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10 μg/mL mouse epidermal growth factor, and 10−10 M cholera toxin A. The cells were plated at a density of 5 × 103 cells/cm2 on 35 mm tissue culture dishes with cover glass bottoms (World Precision Instruments, Inc.). Cells were cultured up to 4 days and the medium changed every 48 hours. Transduction was performed when cells were 70% – 80% confluent.

Generation of lentivirus vector

Using a TOPO® Cloning Reaction (Invitrogen) we cloned our insert DNA (pIRES-AcGFP) containing a green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter cassette into an entry clone pENTR™ TOPO® vector (following manufacturer’s instructions). The insert DNA was transferred into the destination vector pLenti4/ TO/V5-DEST (Invitrogen) by performing the LR recombination reaction (LR Clonase™ II enzyme mix, Invitrogen) using One Shot® Stbl3™ Competent E. coli (Invitrogen), resulting in the generation of our pLenti4/TO/V5-Dest/IRES-AcGFP vector.

We used the ViraPower™ Packaging Mix (Invitrogen), which contains an optimized mixture of three plasmids, pLP1, pLP2, and pLP/VSVG, to produce the lentivirus. Replication-defective VSV-G pseudotyped viral particles were produced by three-plasmid transient cotransfection with the pLenti4/TO/V5-DEST containing GFP-gene into the 293T cell line. Viral supernatants were harvested 48 and 72 hours after transfection, centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C, filtered trough 0.45 μm pore size filters (Millipore Corporation) and stored at −80°C.

Viral vector titers were determined by transduction of HT1080 cells with serially diluted virus supernatants. Transduced cells were counted based on expression of the green fluorescent protein.

Cytofluorimetric analysis of transduced cells

Transduction efficiency of pLenti4/TO/V5-Dest/IRES-AcGFP on rabbit corneal epithelial cells was determined by using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) (DakyoCytomation MoFlo Cell Sorter, Ft. Collins, CO) and a FACScan Cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). For the sorting, we used Summit software, the Enterprise laser with 200 mW of 488 nm, and a 530/30 band-pass filter to detect GFP. For the FACScan, we used CellQuest software, a laser with 15 mW of 488 nm, and a 530/30 band-pass filter to detect GFP.

Transduction efficiency (TE) over time

After 4–5 days post-transfection, cultured cells were harvested and incubated with 2 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI) (to exclude non-viable cells). They were then analyzed on the FACScan for evaluation of the percentage of the GFP-expressing cells. Infected cells were detected on the basis of GFP fluorescence relative to uninfected control. The TE was analyzed at days 0, 3, 5, 8, 11, and 15 post-transfection. We used four cell culture dishes for each analyzed day (n=4).

Dose-response effect on lentiviral transduction efficiency

Transfection was performed using different lentiviral particles (0 cfu/mL, 102 cfu/mL, 103 cfu/mL, 5 × 103 cfu/mL, 104 cfu/mL, 2 × 104 cfu/mL). The cells were harvested and incubated with 2 μg/ml PI prior to analysis by FACScan. They were then analyzed on the FACScan (5th post-transduction day) for evaluation of the percentage of the GFP-expressing cells. Infected cells were detected on the basis of GFP fluorescence relative to uninfected control. We used three cell culture dishes for each lentiviral dilution analyzed (n=3).

Transduction of side population (SP) phenotypic cells

After 4 days post-transfection, cells were prepared for the Hoechst 33342 assay. Hoechst 33342 exclusion assay and FACS for SP were performed according to a previously described method for isolating a SP for hematopoietic stem cells(8) using Hoechst 33342. Transduced cells isolated from their primary cultures were used for the Hoechst 33342 exclusion assay to identify SP. The SP is characterized by low blue and low red fluorescence intensity on a dot-plot displaying dual wavelength of Hoechst blue versus red. This double sorting procedure would allow isolation of presumed corneal epithelial stem cells transduced with GFP-gene.

Statistical analysis

The inferential analysis used in order to confirm or refute the descriptive results was analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare the means of TE from different days analyzed in the experiment “Transduction efficiency over time” and the means of TE from different lentiviral particles analyzed in the experiment “Dose-response effect on lentiviral transduction efficiency”.α ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

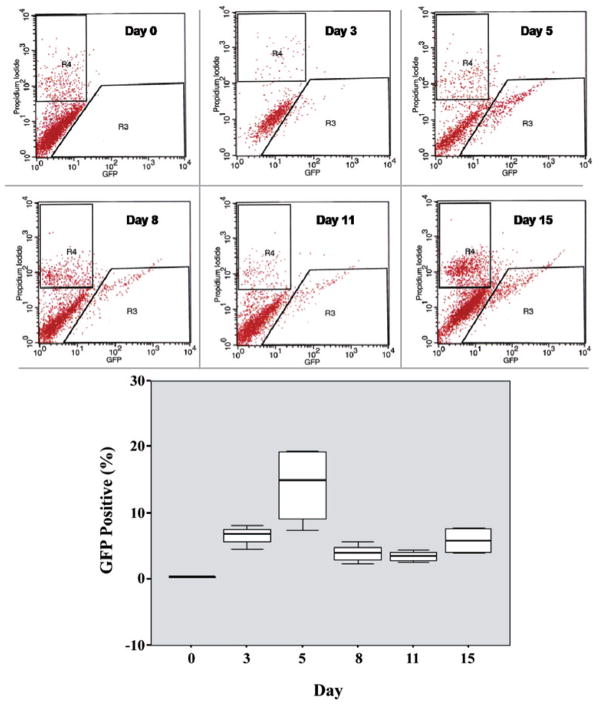

Viable cultures of rabbit corneal epithelial cells were obtained before transduction. GFP expressing lentiviral vectors pLenti4/TO/V5-Dest/IRES-AcGFP were able to effectively transduce primary rabbit corneal epithelial cell culture ex vivo. Live cell imaging post-transduction demonstrated GFP-positive cells with normal epithelial cell morphology and growth (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Live cell imaging post-transduction demonstrating GFP-positive cells with normal epithelial cell morphology and growth. A) Fluorescence imaging; B) Phase-contrast of cultured corneal cells; C) Overlay.

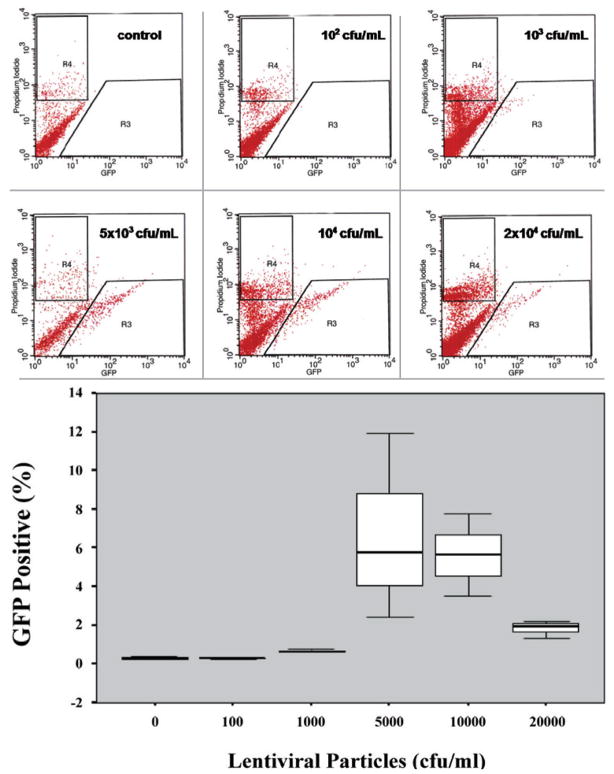

Transduction efficiency over time

When measuring the TE over time we observed that it was close to 7% at day 3 post-transduction and presented a peak of efficiency at day 5 (14.1%). After that, the TE notably decreased tending to stability around 4% to 5%. (Figure 2). The differences in the median values among the different days analyzed were statistically significant (p=0.002).

Figure 2.

Representative histograms (propidium iodide X GFP) demonstrating the identification of GFP (+) cells by FACS for each analyzed day. R3 corresponds to the gate used for isolation of cells expressing GFP. R4 corresponds to the gate used for exclusion of dead cells. Box plot demonstrating the TE over time. The graphic demonstrates the percentage of viable GFP (+) cells for each analyzed day (0, 3, 5, 8, 11, and 15).

The inferential results from ANOVA revealed that the six analyzed days in the experiment A do not present the same logarithmic mean of the measurements (p<0.001).

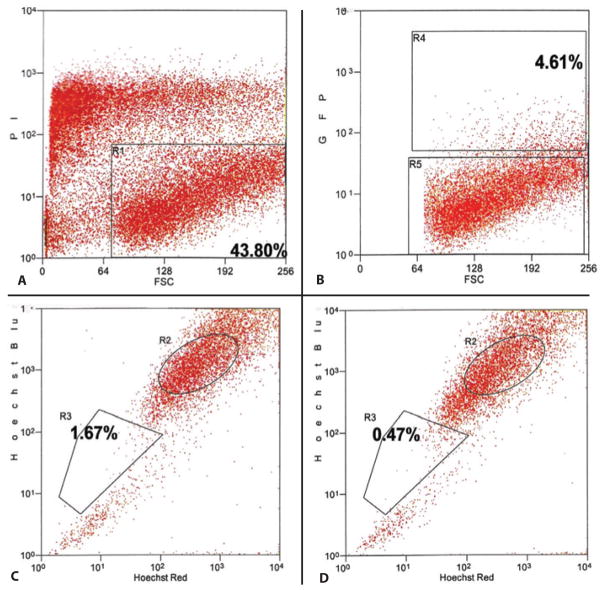

Dose-response effect of different lentiviral particles

The TE using different viral dilutions of our lentivirus vector pLenti4/TO/V5-Dest/IRES-AcGFP during transduction was dose-dependent, and approached an efficiency of approximately 7% using 5 × 103 cfu/mL. It is interesting to note that higher amounts of lentivirus particles did not increase the TE (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Representative histograms (propidium iodide X GFP) demonstrating the identification of GFP (+) cells by FACS for each lentiviral particles dilution used. R3 corresponds to the gate used for isolation of cells expressing GFP. R4 corresponds to the gate used for exclusion of dead cells. Box-plot demonstrating the dose-response effect in TE using different lentiviral particles. It demonstrates the percentage of viable GFP (+) cells for each lentiviral dilution used in the Experiment B (0 cfu/mL, 102 cfu/mL, 103 cfu/mL, 5 × 103 cfu/mL, 104 cfu/mL, 2 × 104 cfu/mL).

The inferential results from ANOVA revealed that the six different lentiviral dilutions (cfu/mL) used in the Experiment B did not present the same logarithmic mean of the measurements (p=0.008).

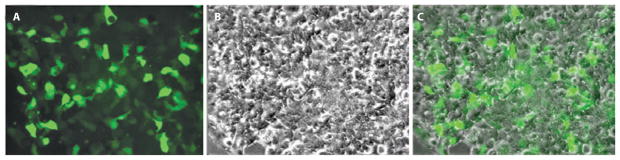

Transduction of side population phenotypic cells

When double sorted by FACS to isolate both GFP positive and side population phenotypic cells, transduced side population cells were identified. The TE in this experiment was 4.61%. The exclusion of Hoechst 33342 to identify the side population was detected in 1.67% of the cells. After incubation with verapamil, the cells excluding the Hoechst 33342 dye approached 0.47% (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Representative histograms demonstrating the identification of transduced side population phenotypic cells by FACS. A) Histogram (propidium iodide X forward scatter) isolating viable cells (gate R1: 43.80%). B) Histogram (GFP X forward scatter) isolating GFP(+) cells (gate R4: 4.61%). C) Histogram (Hoechst blue X Hoechst red) isolating side population phenotypic cells (gate R3: 1.67%). D) Histogram (Hoechst blue X Hoechst red) after incubation with verapamil isolating the subpopulation “side population” (gate R3: 0.47%).

DISCUSSION

Previous investigators have demonstrated functional delivery of genes by non-integrating methods into corneal cells by gene gun(11), electroporation(12), and with adenoviral serotype 5 vectors(13). However, these data were limited to corneal endothelial cells of rat, mice, or rabbit. A few studies have been done reporting gene delivery to primary corneal epithelial cells using transient adenoviral vectors, which is known to promote a short-term transgene expression that ceases after 7–14 days(14–15).

Retrovirus has also been used to transduce corneal cells. Some authors transduced rabbit corneal epithelial cells in vivo and in vitro(16). Some authors demonstrated TE of 22% in human keratocytes and 16% in rabbit keratocytes, ex vivo, using a retroviral vector(17). Those studies demonstrated the retroviral vector’s ability to transduce corneal cells and characterize their stable gene expression.

The use of lentivirus vectors for corneal gene therapy is appealing because the vector stably integrates into the host genome, providing the potential for long-term transgene expression. And different from retroviral vectors, lentiviral do not require mitotic cells to integrate. They integrate into both dividing and non-dividing cells. Wang et al detected gene expression in epithelial and endothelial cells in situ during 60 days when transducing corneas preserved in tissue culture(18). Another research group transduced rat cornea epithelial cells in vivo using lentivirus. They demonstrated a more stable gene expression in the group transduced by lentivirus, suggesting their ability to integrate DNA to the host genome(19). Murthy et al detected the expression of endostatin at the 40th postoperative day of rabbit cornea transplantation previously incubated with lentivirus vector(20).

In our experiment investigating the time-course of gene expression following transduction we observed that 6.6% of the cells were transduced at day 3. Then we observed a peak in the TE at day 5, approaching 14.1%. After day 5 the TE decreased and tended to stability around 4–5% (Figure 2).

These results suggest that presumable stem cells and transient amplifying cells (TAC) were transduced. The trans-duction of TAC might explain the massive transduction between days 3 and 5. A few studies described that TAC increase in number after injury stimulation(4, 21). We believe that the TAC cells were initially stimulated by lentiviral contact and increased their number. That would explain the TE’s peak between days 3 and 5 post-transduction. After a few more days in culture, and without other stimuli to differentiation, they achieved maximum differentiation and started to become nonviable cells. This might explain the TE’s decrease and its tendency to stability after day 5. The inferential results between the analyzed days did not show statistically significantly differences in the TE between days 8 and 11 (p=0.6857), neither between days 8 and 15 (p=0.1052) (Figure 2). Brads-haw et al also observed an early peak of transduction potentially related to TAC transduction. They reported a peak of TE at day 7 post-transduction (using retrovirus) which decreased from the first to the second week and then tended to stability until 9 weeks(16). The tendency to stability is associated to the lentiviral ability to integrate DNA to the host cells genome and consequently to their progeny.

Another hypothesis for the peak observed between days 3 and 5 is that it might require some time for the lentivirus to get into the cells and integrate their DNA. Also, the cell machinery requires some time to express the genetic material inserted. We have not yet examined this hypothesis since our first point of analysis was on day 3.

Once we studied and characterized our vector’s ability to transduce primary corneal epithelial cells ex vivo, we analyzed the dose-effect response. The results demonstrated that the TE was dose dependent comparing different lentiviral particles (p=0.008). The highest TE(s) were obtained with 5 × 103 cfu/mL and 104 cfu/mL lentiviral particles. The paired comparisons between the two lentiviral particle dilutions with the other dilutions showed statistically higher TE than the other lenti-viral particles dilutions. Wang et al demonstrated a positive correlation between the amount of lentiviral particles used to transduce corneal cells and the TE obtained(18). It is relevant to note in our study that higher virus concentration (2 × 104 cfu/mL) did not result in higher TE. The TE obtained with this amount of viral particles was lower than those obtained with 5 × 103 cfu/mL and with 104 cfu/mL (p=0.0040 and p=0.0046, respectively). That observation leads the suspicion of lentiviral toxicity to cultured primary corneal epithelial cells. However, we did not observe morphological cell changes and neither growth rate decrease when we used higher lentivirus particles (data not shown). Also, we did not consider the exclusion of nonviable cells by propidium iodide assay as a parameter for toxicity. Two different studies reported the possible GFP toxicity inducing cell apoptosis when measuring the activity of CPP32, a relevant protease in the apoptotic process(16,22). The probability of lentiviral toxicity associated with GFP toxicity might justify why the TE was not higher when we used higher amounts of lentiviral particles.

Given the eventual desire to achieve long lasting gene expression in the setting of gene therapy, we evaluated the ability of our lentiviral vector to transduce a putative stem cell population. The quest for unique markers of corneal epithelial stem cells continues, however, a number of investigators have isolated putative stem cells functionally as side population cells based on their ability to efflux the Hoechst 33342 dye when sorted by FACS(10,23). Both human(24–25) and rabbit limbal epithelial cells(26) have been sorted in order to isolate the side population (SP) phenotypic cells. Additionally, strong correlations with the expression of ABCG2 markers for human side population limbal cells have been reported reinforcing the characterization of phenotypic corneal epithelial stem cells(24–25). Our results are similar to others comparing the size of the side-population phenotypic cells found. We detected that 0.47% of the cells in our cell suspension, which was obtained from the limbal and whole cornea epithelial layer, demonstrated that phenotype. Some authors, using a cell suspension from rabbit’s limbal area, reported that 0.40% of the cells demonstrated the side-population phenotype(27). When double sorted by FACS using two different channels simultaneously, one to isolate GFP positive cells and the other to isolate side population phenotypic cells, transduced side population cells were identified.

While gene delivery to differentiated corneal epithelial cells will likely have utility for a number of ocular surface diseases, genetic modification of presumed corneal epithelial stem cells may be promising by enabling the production of gene products in their progeny or by providing bioactive proteins to the epithelium early in the repair process.

The use of transduced corneal epithelial cells may augment our ability to treat severe ocular surface disease. Depletion of stem cells leads to cornea vascularization, fibrous tissue growth, and cornea opacification(28). Current techniques for reconstructing the ocular surface damaged by stem cell deficiency involve transplantation of expanded corneal epithelial cells ex vivo, as previously reported(8–9). Cell therapy is a typical example of regenerative medicine. Gene therapy makes regenerative medicine more attractive, since it allows modification of cellular properties by gene introduction before transplanting the tissue to the host. This combination allows exploration of the potential to genetically transform cells that would promote biochemical signals influencing cell proliferation and differentiation, relevant steps in functional tissue repair.

CONCLUSIONS

Lentiviral vectors can effectively transfer heterologous genes to primary corneal epithelial cells expanded ex vivo. Genes were stably expressed over time and could be transferred to mature corneal cells as well as presumable putative stem cells. Transduction efficiency was dose-dependent, however concerns regarding toxicity need further investigation.

Acknowledgments

This work was sponsored in part by an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, the National Eye Institute (NIH) grants K08EY015829 (to MIR) and P30EY12576 (Microscopy Module of Core Grant to U.C. Davis), and by CAPES Ministry of Education, Brazil (PDEE - 0718/05-0).

Footnotes

Work carried out at the University of California - Davis, California, USA.

References

- 1.Mohan RR, Sharma A, Netto MV, Sinha S, Wilson SE. Gene therapy in the cornea. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2005;24(5):537–59. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenblatt MI, Azar DT. Gene therapy of the cornea epithelium. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2004;44(3):81–90. doi: 10.1097/00004397-200404430-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schermer A, Galvin S, Sun TT. Differentiation-related expression of a major 64K corneal keratin in vivo and in culture suggests limbal location of corneal epithelial stem cells. J Cell Biol. 1986;103(1):49–62. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cotsarelis G, Cheng SZ, Dong G, Sun TT, Lavker RM. Existence of slow-cycling limbal epithelial basal cells that can be preferentially stimulated to proliferate: implications on epithelial stem cells. Cell. 1989;57(2):201–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90958-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dua HS, Azuara-Blanco A. Limbal stem cells of the corneal epithelium. Surv Ophthalmol. 2000;44(5):415–25. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(00)00109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tseng SC. Concept and application of limbal stem cells. Eye (Lond) 1989;3(Pt 2):141–57. doi: 10.1038/eye.1989.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buck RC. Measurement of centripetal migration of normal corneal epithelial cells in the mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1985;26(9):1296–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pellegrini G, Traverso CE, Franzi AT, Zingirian M, Cancedda R, De Luca M. Long-term restoration of damaged corneal surfaces with autologous cultivated corneal epithelium. Lancet. 1997;349(9057):990–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)11188-0. Comment in: Lancet 1997, 349, 9064–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwab IR, Reyes M, Isseroff RR. Successful transplantation of bioengineered tissue replacements in patients with ocular surface disease. Cornea. 2000;19(4):421–6. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200007000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodell MA, Brose K, Paradis G, Conner AS, Mulligan RC. Isolation and functional properties of murine hematopoietic stem cells that are replicating in vivo. J Exp Med. 1996;183(4):1797–806. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zagon IS, Sassani JW, Verderame MF, McLaughlin PJ. Particle-mediated gene transfer of opioid growth factor receptor cDNA regulates cell proliferation of the corneal epithelium. Cornea. 2005;24(5):614–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000153561.89902.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oshima Y, Sakamoto T, Yamanaka I, Nishi T, Ishibashi T, Inomata H. Targeted gene transfer to corneal endothelium in vivo by electric pulse. Gene Ther. 1998;5(10):1347–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larkin DF, Oral HB, Ring CJ, Lemoine NR, George AJ. Adenovirus-mediated gene delivery to the corneal endothelium. Transplantation. 1996;61(3):363–70. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199602150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiao J, Natarajan K, Rajala MS, Astley RA, Ramadan RT, Chodosh J. Vitronectin: a possible determinant of adenovirus type 19 tropism for human corneal epithelium. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(3):363–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.077. Erratum in: Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141(2):432. Nataraja, Kanchana [corrected to Natarajan, Kanchana] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Z, Mok H, Pflugfelder SC, Li DQ, Barry MA. Improved transduction of human corneal epithelial progenitor cells with cell-targeting adenoviral vectors. Exp Eye Res. 2006;83(4):798–806. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bradshaw JJ, Obritsch WF, Cho BJ, Gregerson DS, Holland EJ. Ex vivo transduction of corneal epithelial progenitor cells using a retroviral vector. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40(1):230–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seitz B, Moreira L, Baktanian E, Sanchez D, Gray B, Gordon EM, et al. Retroviral vector-mediated gene transfer into keratocytes in vitro and in vivo. Am J Ophthal-mol. 1998;126(5):630–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(98)00205-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X, Appukuttan B, Ott S, Patel R, Irvine J, Song J, et al. Efficient and sustained transgene expression in human corneal cells mediated by a lentiviral vector. Gene Ther. 2000;7(3):196–200. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Igarashi T, Miyake K, Suzuki N, Kato N, Takahashi H, Ohara K, et al. New strategy for in vivo transgene expression in corneal epithelial progenitor cells. Curr Eye Res. 2002;24(1):46–50. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.24.1.46.5436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murthy RC, McFarland TJ, Yoken J, Chen S, Barone C, Burke D, et al. Corneal transduction to inhibit angiogenesis and graft failure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(5):1837–42. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park KS, Lim CH, Min BM, et al. The side population cells in the rabbit limbus sensitively increased in response to the central cornea wounding. Invest Ophthal-mol Vis Sci. 2006;47(3):892–900. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Detrait ER, Bowers WJ, Halterman MW, Giuliano RE, Bennice L, Federoff HJ, et al. Reporter gene transfer induces apoptosis in primary cortical neurons. Mol Ther. 2002;5(6):723–30. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Z, de Paiva CS, Luo L, Kretzer FL, Pflugfelder SC, Li DQ. Characterization of putative stem cell phenotype in human limbal epithelia. Stem Cells. 2004;22(3):355–66. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.22-3-355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watanabe K, Nishida K, Yamato M, Umemoto T, Sumide T, Yamamoto K, et al. Human limbal epithelium contains side population cells expressing the ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCG2. FEBS Lett. 2004;565(1–3):6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Paiva CS, Chen Z, Corrales RM, Pflugfelder SC, Li DQ. ABCG2 transporter identifies a population of clonogenic human limbal epithelial cells. Stem Cells. 2005;23(1):63–73. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Budak MT, Alpdogan OS, Zhou M, Lavker RM, Akinci MA, Wolosin JM. Ocular surface epithelia contain ABCG2-dependent side population cells exhibiting features associated with stem cells. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 8):1715–24. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Umemoto T, Yamato M, Nishida K, Yang J, Tano Y, Okano T. Limbal epithelial side-population cells have stem cell-like properties, including quiescent state. Stem Cells. 2006;24(1):86–94. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tseng SC. Regulation and clinical implications of corneal epithelial stem cells. Mol Biol Rep. 1996;23(1):47–58. doi: 10.1007/BF00357072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]