Abstract

New agents and treatment strategies that can be safely and effectively integrated into current treatment paradigms for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) are urgently needed. To date, the anti-EGF receptor (EGFR) monoclonal antibody, cetuximab, is the first and only molecularly targeted therapy to demonstrate a survival benefit for patients with recurrent or metastatic disease. Other anti-EGFR-targeted therapies, including monoclonal antibodies (e.g., panitumumab and zalutumumab) and reversible and irreversible ErbB family tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g., lapatinib, afatinib and dacomitinib) are being actively investigated in Phase II and Phase III clinical trials. In addition, validated biomarkers are needed to predict clinical benefit and resistance to anti-EGFR therapy in HNSCC. This review will compare and contrast the mechanisms of action of anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies and tyrosine kinase inhibitors and also discuss their role in the management of HNSCC and the potential impact of human papillomavirus status in the development of these targeted agents.

Keywords: epidermal growth factor receptor, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, HER tyrosine kinase receptor family, therapeutic monoclonal antibody, tyrosine kinase inhibitor

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is a heterogeneous disease occurring at multiple subsites within the head and neck region, including the oral cavity, pharynx and larynx, with an estimated 52,140 new cases in the USA in 2011 [1]. The causes of HNSCC include tobacco and excessive alcohol use [2,3], while high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection has also been found to cause oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, a subgroup of HNSCC [4]. While the development of multimodality treatments, including any given combination and sequence of surgery, chemotherapy and radiation, has improved survival for locally advanced HNSCC, the management of recurrent and/or metastatic disease is still a clinical challenge [5–8].

Traditionally, the prognostic assessment of a given patient has been largely based on clinical parameters such as performance status and disease stage. However, there is significant heterogeneity within these patient groups and their clinical outcomes. Therefore, several bio-markers have been examined to further delineate biologically homogeneous patient groups, which may provide more accurate prognostic and predictive information. To date, EGF receptor (EGFR) expression levels within the tumors and HPV status are the most promising prognostic biomarkers. Patients with tumors having higher EGFR protein expression have been strongly associated with poorer prognosis [9,10]. Patients with HPV-positive disease have shown more favorable outcomes compared with patients with HPV-negative disease [11], resulting in routine testing of HPV status in patients with oro-pharyngeal primary tumors. In both biomarker multivariate analyses, the laboratory data have added independent prognostic information to clinical parameters.

In addition to being a laboratory-based prognostic biomarker, EGFR has emerged as a promising therapeutic target and has sparked a surge in the development of both anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). In HNSCC, EGFR-targeted mAbs are the only biological agents so far that have provided overall survival (OS) benefits in combination with radiation or chemotherapy [8,12]. Also, EGFR and HPV status are being further analyzed in clinical context because it has been suggested that there is an interaction between expression levels of EGFR and HPV status [13]. Currently, the management of HNSCC is being actively re-evaluated to decrease treatment-related toxicities in HPV-positive patients and improve survival outcomes in HPV-negative patients. This paradigm shift in treatment strategies for HNSCC has provided a golden opportunity to introduce novel agents and indications in current clinical trials. This review will compare and contrast the mechanism of action of anti-EGFR mAbs and TKIs and discuss their role in the management of HNSCC and the potential impact of HPV status in the development of these targeted agents.

Targeting ErbB family tyrosine kinase receptors in HNSCC

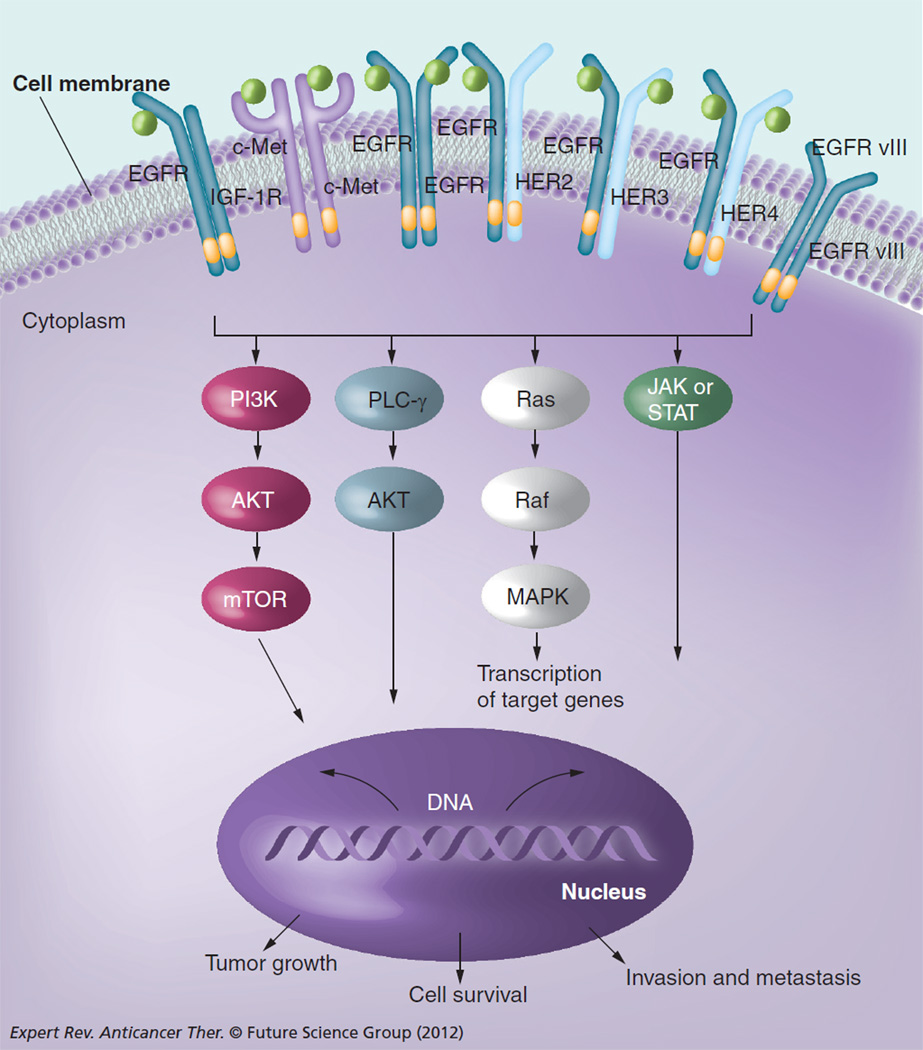

EGFR (ErbB1/HER1) is a member of the ErbB tyrosine kinase family, which also includes HER2 (ErbB2), HER3 (ErbB3) and HER4 (ErbB4) [14]. This family of receptors modulates cell proliferation, survival, adhesion, migration and differentiation. Ligand binding is followed by homodimerization or heterodimerization among members of the ErbB family receptors, as well as other cell-surface tyrosine kinase receptors, such as IGF 1 receptor (IGF-1R) and c-Met (Figure 1) [15–18]. Dimerization of these receptors leads to the activation of tyrosine kinase and autophosphorylation of tyrosine residues in the C-terminal tail of the receptor and subsequent activation of downstream effector proteins, including MAPK, PI3K/AKT, phospholipase C-γ, PKC and STAT, resulting in the transcription of genes involved in proliferation and survival. Aberrant activity of these receptors plays a key role in oncogenesis of a variety of tumors, including HNSCC.

Figure 1. Oncogenic signaling pathways targeted by anti-EGF receptor monoclonal antibodies and ErbB/HER family tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Dimerization and activation of ErbB/HER family receptors leads to increased signaling through downstream signaling pathways that promote growth, invasion/metastasis and survival. Other receptors (c-Met, IGF-1R) may also dimerize or crosstalk with ErbB family members and activate downstream signaling.

AKT: Protein kinase B; EGFR: EGF receptor; HER: Human EGFR; IGF-1R: IGF 1 receptor; PLC- γ: Phospholipase C-γ; STAT: Signal transducers and activators of transcription.

In HNSCC, EGFR is frequently over-expressed (80–90%) [9,19,20], but activating mutations in the receptor commonly seen in non-small-cell lung cancer are rare (~0–7% depending on patient population) [21–23]. Currently, there are two therapeutic approaches to inhibit EGFR: anti-EGFR mAbs and TKIs (Table 1). While both approaches strive for complete inhibition of receptor signal transduction, several studies have shown that cells can have differential sensitivities to these two modes of EGFR inhibition. The mAbs target the extracellular domain of the receptor and block ligand binding and dimerization, which in turn stops receptor activation and signal transduction. In addition, mAbs such as cetux-imab (Erbitux®, Bristol-Myers Squibb, NY, USA) have been shown to induce antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) [24]. The TKIs target the tyrosine kinase domain of the intracellular domain of the receptor by competing for the ATP binding pocket, thus inhibiting phosphorylation of the receptor and its downstream targets. Owing the fact that the tyrosine kinase domains within ErbB family receptors share significant structural homology, development of TKIs that inhibit more than one of the receptors within the family is feasible, and subsequent inhibition of receptor crosstalk through heterodimerization is considered to be a significant advantage over therapeutic antibodies. For example, when the ErbB family receptors are activated by binding of the ligands, they form an asymmetric kinase dimer by one kinase serving as the ‘donor’ and the other serving as the ‘acceptor’. Only the ‘donor’ kinase is active and phosphorylates the c-terminal tail of the other receptor within the dimer. Therefore, even in the presence of an EGFR-specific TKI, the phosphorylation sites of EGFR located in the c-terminal tail within the intra cellular domain can still be phosphorylated by the tyrosine kinase of HER2, if HER2 serves at the active donor kinase upon heterodimerization [25,26]. EGFR that is phosphorylated by HER2 can then activate the downstream pathways. Development of therapeutic antibodies recognizing both EGFR and HER2 with a required specificity is not feasible, although some view this level of specificity to be an advantage because of the potential for fewer off-target effects compared with TKIs. Understanding these key differences is important in explaining resistance mechanisms, and significant to the improvement in efficacy of current agents and development of predictive biomarkers for future clinical trials and appropriate patient selection.

Table 1.

ErbB/HER family members in clinical trials for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

| Agent | Target (s) | Phase of development in HNSCC† |

|---|---|---|

| Monoclonal antibodies | ||

| Cetuximab | EGFR | Approved |

| Panitumumab | EGFR | III |

| Zalutumumab | EGFR | III |

| Nimotuzumab | EGFR | III‡ |

| Tyrosine kinase inhibitors | ||

| Lapatinib (reversible) | EGFR and HER2 | III |

| Afatinib (irreversible) | EGFR, HER2 and HER4 | III |

| Erlotinib (reversible) | EGFR | II§ |

| Dacomitinib (irreversible) | EGFR, HER2 and HER4 | II |

Includes agents with at least one clinical trial in HNSCC indexed on [102] as of April 2012.

Highest phase for which at least one trial (monotherapy or with chemotherapy and/or radiation irrespective of treatment setting [neoadjuvant, adjuvant and primary treatment]) was recruiting or active but not recruiting per [102] as of April 2012.

Approved for treating HNSCC in some non-USA countries.

Phase III trials had been initiated but were terminated early for low accrual, as per [102] summaries.

EGFR: EGF receptor; HER: Human EGFR; HNSCC: Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

Currently available EGFR-targeted agents

To date, cetuximab is the only EGFR-targeted agent approved by the US FDA for HNSCC [101]. Cetuximab is a monoclonal, chimeric (human/mouse) antibody against EGFR. The mechanisms of action mediated by cetuximab in patients are thought to be twofold: direct binding to EGFR, inhibiting ligand binding and phosphorylation [27] and induction of ADCC, consequently clearing antibody-coated cells by the host immune system [28,29]. While the anticancer effects of cetuximab via inhibition of signal transduction have been well established, the contribution of ADCC needs to be further delineated. Although the response rate to cetuximab monotherapy is limited to 13% in recurrent or metastatic HNSCC (Table 2) [30], it is the first targeted therapy to show a significant improvement in OS for patients with locally advanced disease when in combination with radiation [12] or for recurrent or metastatic disease when in combination with chemotherapy [8]. In evaluating cetuximab plus high-dose radiation for locally advanced HNSCC (n = 424), the improvement in OS with combined therapy (49.0 vs 29.3 months for high-dose radiation alone; hazard ratio [HR]: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.57–0.97; p = 0.03) was accompanied by improvements in the primary end point of median duration of locoregional control (24.4 vs 14.9 months; HR: 0.68; 95% CI: 0.52–0.89; p = 0.005) and the secondary end point of median progression-free survival (PFS; 17.1 vs 12.4 months; HR: 0.70; 95% CI: 0.54–0.90; p = 0.006) [12]. When cetuximab was added to platinum–fluorouracil chemotherapy in a recurrent or metastatic HNSCC population (n = 442), the median OS (primary end point) was 10.1 versus 7.4 months for chemotherapy alone (HR: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.64–0.99; p = 0.04), with additional improvements observed in median PFS (5.6 vs 3.3 months; HR: 0.54; 95% CI: 0.43–0.67; p < 0.001) and response rate (36 vs 20%; p < 0.001) [8].

Table 2.

Efficacy data from clinical trials evaluating ErbB/HER family inhibitors as monotherapy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

| Study | Phase (n) |

Therapy | Setting | RR (%) | TTP | PFS | OS | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vermorkenet al. (2007) |

Phase II (n = 103) |

Cetuximab (mAb) |

Previously treated recurrent/metastatic HNSCC |

13 | 70 days | NR | 178 days | [30] |

| Machiels et al. (2011) |

Phase III (n = 286) |

Zalutumumab (mAb) + BSC versus BSC alone |

Previously treated recurrent/metastatic HNSCC |

6.3 versus 1.1 | NR | 9.9 versus 8.4 weeks (HR: 0.63; 95% CI: 0.47–0.84; p = 0.0012) |

6.7 versus 5.2 months (HR: 0.77; 97.06% CI: 0.57–1.05; p = 0.0648) |

[59] |

| Thomas et al. (2007) |

Phase II (n = 31) |

Erlotinib (TKI) | Neoadjuvant, nonmetastatic HNSCC |

29 | NR | NR | NR | [82] |

| Soulieres et al. (2004) |

Phase II (n = 115) |

Erlotinib (TKI) | Untreated or previ- ously treated recurrent/metastatic HNSCC |

4.3 | NR | 9.6 weeks (95% CI: 8 .1–12.1) |

6.0 months (95% CI: 4. 8 –7.0 ) |

[61] |

| Cohen et al. (2005) |

Phase II (n = 71) |

Gefitinib (TKI) | Untreated or previ- ously treated recurrent/metastatic HNSCC |

1.4 | NR | 1.8 months (95% CI: 1.7– 3.1) |

5.5 months (95% CI: 4.0–7.0) |

[36] |

| Cohen et al. (2003) |

Phase II (n = 52) |

Gefitinib (TKI) | Previously treated recurrent/metastatic HNSCC |

10.6 | 3.4 months (95% CI: 1.8 –3.6 ) |

NR | 8.1 months (95% CI: 5.2–9.4) |

[62] |

| Chua et al. (2008) |

Phase II (n = 19) |

Gefitinib (TKI) | Previously treated recurrent/metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma |

0 | 4 months (95% CI: 2.6–5.4) |

NR | 16 months | [83] |

| Ma et al. (2008) | Phase II (n = 16) |

Gefitinib (TKI) | Previously treated recurrent/metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma |

0 | 2.7 months |

NR | 12 months | [84] |

| Stewart et al. (2009) |

Phase III (n = 486) |

Gefitinib (TKI) 250 mg versus gefitinib 500 mg versus MTX |

Untreated recurrent/ metastatic HNSCC |

2.7 (OR vs MTX: 0.69; 95% CI: 0.19– 2.50; p = 0.57) versus 7.6 (OR vs MTX: 2.04; 95% CI: 0.74– 5.56; p = 0.17) versus 3.9 |

NR | NR | 5.6 months (HR vs MTX: 1.22; 95% CI: 0.95–1.57; p = 0.12) versus 6.0 months (HR vs MTX: 1.12; 95% CI: 0.87–1.43; p = 0.39) versus 6.7 months |

[34] |

| del Campo et al. (2011) |

Phase II (n = 107) |

Lapatinib (TKI) versus placebo |

Untreated locally advanced HNSCC |

17 versus 0† | NR | NR | NR | [65] |

| de Souza et al. (2012) |

Phase II (n = 45) |

Lapatinib (TKI) | Recurrent/metastatic HNSCC without (arm A) or with (arm B) prior EGFR inhibitor exposure |

A: 0; B: 0 | NR | A: 52 days; B: 52 days |

A: 288 days; B: 155 days |

[66] |

| Seiwert et al. (2011) |

Phase II (n = 124) |

Afatinib (TKI) versus cetuximab |

Previously treated recurrent/metastatic HNSCC |

19.2 versus 7.3 | NR | 15.9 versus 15.1 weeks |

NR | [71] |

| Siu et al. (2011) | Phase II (n = 69) |

Dacomitinib (TKI) |

Untreated recurrent/ metastatic HNSCC |

11 | NR | 2.8 months (95% CI: 2.6 – 4 .1) |

7.6 months (95% CI: 6 . 4 –12) |

[74] |

Independent evaluation (intent-to-treat).

BSC: Best supportive care; EGFR: EGF receptor; HER: Human EGFR; HNSCC: Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; HR: Hazard ratio; mAb: Monoclonal antibody; MTX: Methotrexate; NR: Not reported; OR: Odds ratio; OS: Overall survival; PFS: Progression-free survival; RR: Response rate; TKI: Tyrosine kinase inhibitor; TTP: Time to progression.

It is noteworthy that the aforementioned trial of cetuximab plus radiation was initiated prior to the adoption of chemoradiation as the standard of care in this setting, and provides the only evidence of an OS benefit for this combination (unlike cisplatin-based chemoradiation, which has demonstrated improved OS over radiation alone in multiple trials). The lack of a randomized comparison of cetuximab versus cisplatin given with radiation for locally advanced HNSCC has been cited as a major barrier to the acceptance of cetuximab as a substitute for cisplatin in this setting [31]. This question is currently being asked through a Phase III trial comparing cisplatin and radiation versus cetuximab and radiation in locally advanced and HPV-positive HNSCC patients (Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 1016; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01302834) [102]. Additionally, the OS benefits for patients with HNSCC are not without associated toxicities. The most common toxicity is skin rash (~90%) [32], which in most cases is manageable, but can be severe enough to require dose reduction or cessation of treatment [33]. Moreover, cetuximab treatment has been associated with infusion reactions that can be life threatening [32] and administration may be logistically challenging for patients owing to weekly intravenous dosing requirements.

Several studies have been evaluated to determine potential biomarkers for prediction of treatment response with current EGFR inhibitors. In a Phase III study of gefitinib 500 or 250 mg compared with methotrexate for recurrent or metastatic HNSCC, increased EGFR gene copy number appeared to correlate with response to gefitinib (13.8 vs 3.6 vs 0%, respectively) but not with OS (5.9 vs 6.1 vs 7.6 months, respectively) [34]. In the Phase III cetuximab study described above [8], there was no association between EGFR gene copy number and OS, PFS or best overall response for patients treated with cetuximab plus platinum–fluorouracil chemotherapy [35]. In a Phase II study of gefitinib for recurrent and/or metastatic HNSCC, disease control, PFS and OS were significantly correlated with grade of cutaneous toxicity (p = 0.001, p = 0.001 and p = 0.008, respectively) [36]. Likewise, in a Phase III study of cisplatin plus placebo or cetuximab for recurrent/metastatic HNSCC, OS was significantly longer in the cetuximab group in patients developing skin rash (p = 0.01) [37]. These studies suggest that there is no correlation between EGFR analyses and response, with the only potential biomarker predicting response being the clinical assessment of rash rather than laboratory testing.

To address this issue, better understanding of EGFR inhibitor resistance mechanisms is required. Several studies suggest various mechanisms of resistance to cetuximab. An example is the presence of EGFR variant III (EGFRvIII), which is the most common variant observed in approximately 40% of HNSCC cases [38]. EGFRvIII contains a truncated ligand binding domain (missing exon 2–7), resulting in ligand-independent, constitutive activation of the receptor (Figure 1) [39– 41]. There have been reports of cetuximab binding to EGFRvIII [42]. However, in vitro studies using HNSCC cell lines showed that cetuximab binding to EGFRvIII did not inhibit EGFRvIII-mediated cell migration [43]. Therefore, the addition of anti-EGFR therapy targeting the extracellular ligand binding domain may not be effective against HNSCC expressing EGFRvIII. Other key resistance mechanisms are the upregulation of ligands to compete with cetuximab for receptor binding and also heterodimerization of receptors, which results in continued signaling of EGFR through receptor crosstalk (involving other members of the ErbB family, such as HER2 and HER3 [44–46], and other tyrosine kinase receptors, such as c-Met and IGF-1R) [44,45,47]. Crosstalk between G protein-coupled receptors and EGFR is also thought to occur, and G protein-coupled receptor-induced transactivation of tyrosine kinase receptors has been implicated in the development and progression of malignancy and resistance to TKIs [48]. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition has also been shown to adversely influence response to cetuximab in HNSCC (as previously observed with other agents, including gefitinib) [49], with evidence that the mesenchymal components of HNSCC may have a propensity for resistance to cetuximab monotherapy [50,51] and that failure of cetuximab as a radiosensitizer may coincide with the initiation of the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition [52].

Novel EGFR-targeted agents in development

In an effort to improve upon the clinical benefits of cetuximab for HNSCC, either by increasing efficacy or decreasing toxicities, several agents are in various stages of the drug development pipeline (Table 1).

New generation of mAbs targeting EGFR

With the initial success of cetuximab, there are several other mAbs in clinical development for HNSCC, including panitumumab ( Vectibix®, Amgen, CA, USA), zalutumumab (Genmab, Copenhagen, Denmark), and nimotuzumab (YM Biosciences, ON, Canada). While these newer mAbs share similar features with cetuximab, such as specifically targeting the extracellular ligand-binding domain of EGFR and a relatively long half-life, there is a significant difference in antibody composition. The newer mAbs are either humanized or fully human and thus thought to be less immunogenic than cetuximab, which is a mouse–human chimeric mAb. Among the numerous EGFR-targeted mAbs other than cetuximab, panitumumab and zalutumumab have been tested in HNSCC in large-scale clinical trials.

Panitumumab is a fully humanized anti-EGFR mAb with a half-life of 7.5 days [53]. It is currently approved for the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer without the KRAS mutation [103]. Panitumumab has been shown to be safe as monotherapy in patients with HNSCC in a Phase II trial [54] and was recently tested in a Phase III clinical trial (SPECTRUM; n = 657) in metastatic or recurrent HNSCC in combination with standard platinum-based chemotherapy. Primary efficacy data from this ongoing study reported no significant improvement in median OS with the addition of panitumumab to chemotherapy (11.1 vs 9.0 months for chemotherapy alone; HR: 0.87; 95% CI: 0.73–1.05; p = 0.14), but did report improved PFS versus chemotherapy alone (5.8 vs 4.6 months; HR: 0.78; 95% CI: 0.66–0.92; p = 0.004) [55]. The most common grade ≥3 adverse events (panitumumab plus chemotherapy vs chemotherapy alone) were neutropenia (32 vs 33%), skin toxicity (17 vs 1%), anemia (12 vs 14%) and hypomagnesemia (12 vs 3%). Infusion reactions of any grade occurred in <1% of patients in each group. Panitumumab is an IgG2 isotype, while cetuximab is an IgG1 isotype. Unlike an IgG1 isotype, IgG2 isotypes do not induce ADCC and have lower complement activation [56–58]. If further studies show that ADCC is indeed an important effect of anti-tumor activity, patients with a competent immune system who are treated with panitumumab may not have the same anti-tumor activity as those treated with other antibodies of IgG1 isotype.

Zalutumumab is a fully human anti-EGFR antibody. In a Phase III clinical trial of 286 patients with recurrent or metastatic HNSCC who failed standard platinum-based therapy, patients who received zalutumumab had a median OS of 6.7 months compared with 5.2 months in patients who received best supportive care alone (HR: 0.77; 97.06% CI: 0.57–1.05; p = 0.0648) (Table 2) [59]. While an OS increase of 1.5 months was not statistically significant, patients who received zalutumumab had signifi-cantly prolonged PFS versus best supportive care (9.9 vs 8.4 weeks; HR: 0.63; 95% CI: 0.47–0.84; p = 0.0012). The most common grade 3/4 adverse events were rash (21% zalutumumab group vs none in control group), anemia (6 vs 5%) and pneumonia (5 vs 2%). Grade 3/4 infusion-related reactions occurred in 4% of zalutumumab-treated patients.

The toxicity profiles of these new mAbs are comparable to that of cetuximab, although they appear to be associated with less hypersensitivity or infusion reactions. Again these mAbs need to be administered by intravenous infusion, which requires frequent clinic visits. Because the EGFR-targeted approaches of these agents are similar to cetuximab, the proposed resistance mechanisms to cetuximab may be equally applicable to the new mAbs in development.

New generation of receptor TKIs targeting EGFR

Aside from mAbs, EGFR has also been targeted using investigational TKIs in HNSCC clinical trials. TKIs with planned or ongoing Phase III clinical trials are summarized in Table 3. In contrast to mAbs, which bind to the extracellular ligand-binding domain of EGFR, TKIs target the intracellular tyrosine kinase domain and compete for the ATP binding pocket within the tyrosine kinase domain. Inhibition of ATP binding results in inhibition of phosphorylation and subsequent downstream signaling mediators. The early development of TKIs with agents such as gefitinib (Iressa®, AstraZeneca, DE, USA) and erlotinib (Tarceva®, Genentech, CA, USA) in recurrent or metastatic HNSCC has been disappointing, with overall objective response rates ranging from 1.4 to 10.6% (Table 2) [36,60–62]. However, a new generation of TKIs is showing potential promise in HNSCC.

Table 3.

Ongoing Phase II and III clinical trials evaluating ErbB/HER family inhibitors as monotherapy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

| Trial identifer | Estimated enrollment (n) |

Patient population | Therapy | Anticipated study completion |

Primary end point |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT00661427 (Phase II) | 61 | Previously treated recurrent/metastatic HNSCC |

Cetuximab | May 2012 | RR |

|

NCT00446446 (PRISM; Phase II) |

52 | Previously treated recurrent/metastatic HNSCC |

Panitumumab | July 2011 | RR |

| NCT00542308 (Phase II) | 100 | Previously treated recurrent/metastatic HNSCC |

Zalutumumab/BSC | Completed† | OS |

| N C T 01415 674 (PREDICTOR; Phase II) |

60 | Untreated nonmetastatic HNSCC |

Afatinib | April 2013 | Biomarkers |

|

NCT01345669 (LUX-Head & Neck 2; Phase III) |

669 | Locoregionally advanced HNSCC treated with chemoradiotherapy |

Afatinib versus placebo |

April 2015 | DFS |

|

NCT01345682 (LUX-Head & Neck 1; Phase III) |

474 | Previously treated recurrent/metastatic HNSCC |

Afatinib versus methotrexate |

March 2014 | PFS |

| NCT01427478 (Phase III) | 315 | Untreated nonmetastatic HNSCC after postoperative radiochemotherapy |

Afatinib maintenance |

September 2016 | DFS |

| NCT01449201 (Phase II)‡ | 49 | Previously treated HNSCC | Dacomitinib | April 2013 | RR |

Includes trials indexed on [102] as of April 2012.

Results awaited.

Study is not yet open for participant recruitment.

BSC: Best supportive care; DFS: Disease-free survival; HER: Human EGF receptor; HNSCC: Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma; OS: Overall survival; PFS: Progression-free survival; RR: Response rate

The most important differences between erlotinib or gefitinib and newer TKIs in development are that many of these newer agents are multikinase inhibitors and/or bind irreversibly to the ATP pocket. As mentioned before, the receptors dimerize upon ligand binding and activation. If autophosphorylation of EGFR by its own tyrosine kinase is inhibited, the tyrosine kinase of other ErbB family members, IGF-1R or c-MET, can sFtill phosphorylate EGFR and activate the downstream signaling cascade by heterodimerization or receptor crosstalk (Figure 1). Therefore, inhibiting other members of the ErbB receptor family such as HER2 and HER4, in addition to EGFR, may prevent potential escape signaling through heterodimerization. Below, a few examples of these next-generation TKIs are described. Ongoing clinical trials of the various ErbB family inhibitors discussed herein are summarized in Table 3.

Lapatinib (Tykerb®, GlaxoSmithKline, NC, USA) is a reversible TKI with specificity against both EGFR and HER2 [63]. It is currently approved by the FDA for the treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer overexpressing HER2 who have received prior therapy (anthracycline, taxane and trastuzumab) [104]. A randomized Phase II clinical trial (n = 67) evaluated lapatinib in combination with cisplatin and radiation versus chemoradiotherapy alone in patients with locally advanced HNSCC [64]. The complete response rate 6 months after chemoradiotherapy was 53% with lapatinib versus 36% with placebo. Grade 3/4 toxicities were balanced between treatment arms, with grade 3 rash (3%) and diarrhea (6%) more frequent with lapatinib. While lapatinib monotherapy in patients with recurrent or metastatic disease did not show significant activity in two previous studies (Table 2) [65,66], the combination with cisplatin and radiation in a p16-negative (a surrogate marker of HPV-negative) patient population showed a positive signal [67], suggesting further development of lapatinib in combination with radiation may be warranted.

Afatinib (BIBW 2992, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim, Germany) is an orally available, irreversible ErbB family blocker with inhibitory effects on EGFR, HER2 and HER4 [68,69]. In a Phase I trial (n = 53) of afatinib in patients with advanced solid tumors, the reported dose-limiting toxicities were grade 3 rash (n = 2) and reversible grade 3 dyspnea (n = 1) [70]. In a recent randomized Phase II study (n = 124), afatinib showed anti-tumor activity that appeared to be comparable with that of cetuximab in patients with metastatic or recurrent HNSCC after failing platinum therapy (Table 2) [71]. Confirmed objective response rate in 106 evaluable patients was 19.2% with afatinib and 7.3% with cetuximab. Median PFS was 15.9 weeks in the afatinib group and 15.1 weeks in the cetuximab group (p = 0.93). The most common afatinib-related adverse events were diarrhea and skin-related events, while the most common adverse events with cetuximab were skin related. While these data are taken from a small randomized Phase II study and Phase III data for direct comparison with cetuximab or to a routinely used chemotherapy regimen are not available, afatinib appears to be an active agent in the management of HNSCC.

Dacomitinib (PF00299804, Pfizer, NY, USA) is an oral, irreversible small molecule pan-HER inhibitor, meaning it can inhibit EGFR, HER2 and HER4 [72]. In preclinical studies, it has shown activity against both wild-type and mutant receptors, including EGFRvIII [72]. The Phase II dose was established to be 45 mg once daily, and with a relatively long half-life, it has sustained exposure [73]. In a report from a Phase II trial in recurrent/metastatic HNSCC (n = 69), dacomitinib showed anti-tumor activity as first-line treatment, with an objective response rate of 11% (Table 2) [74]. The most common grade 3 treatment-related adverse events (>3%) included diarrhea (13%), fatigue (9%), dermatitis acneiform (7%) and hand–foot reaction (4%).

One distinct advantage of TKIs over mAbs is their oral availability, hence eliminating one of the main side effects of mAbs (i.e., infusion reactions) and providing more convenient dosing compared with intravenous infusion that requires outpatient visits. Also, the irreversible inhibitors have the potential advantage of prolonged clinical effects with less frequent dosing, which may increase patient adherence. However, oral TKIs may have increased gastrointestinal toxicities compared with cetuximab, such as diarrhea. In addition, the new generation of TKIs has a theoretical advantage over the mAbs for targeting the intracellular tyrosine kinase domain in the presence of EGFRvIII, with ligand-independent receptor activation. Also, multikinase inhibitors may inhibit persistent activation of EGFR through heterodimerization by inhibiting other ErbB family receptors.

Implication of EGFR and HPV interaction in the development of EGFR inhibitors

As mentioned earlier, HPV-positive status is a favorable prognostic indicator and predicts therapeutic benefit with induction chemotherapy and chemoradiotherapy [13,75,76] or radiotherapy alone [77] for patients with HNSCC. Data from a biomarker analysis of a small study showed that HPV positivity and EGFR expression were inversely related [76], and patients with HPV-positive disease and low EGFR expression had the best prognosis and response to treatment [13]. Another study confirmed this inverse relationship between HPV status and EGFR expression, suggesting that EGFR and HPV are independent prognostic markers in oropharyngeal cancer [78]. However, the role of HPV status and response to EGFR inhibitors is unclear. In a biomarker analysis of data from four clinical trials in relapsed or metastatic HNSCC (two trials involving erlotinib and two involving non-EGFR-targeted therapies), HPV status was not predictive of response to therapy [79]. Similarly, biomarker analysis of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 2303 study showed no significant association between HPV status and response or survival with cetuximab/chemoradiotherapy for HNSCC [80]. By contrast, a retrospective analysis showed improved OS in HPV-positive patients treated with radiotherapy plus an EGFR inhibitor versus those treated with chemotherapy plus radiotherapy (2-year OS, 80 vs 60%; HR: 0.15; 95% CI: 0.02–0.77; p = 0.03) [81], suggesting a potential benefit with EGFR inhibitors in patients with HPV-positive HNSCC. Ongoing trials (e.g., ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT01084083 and NCT01302834 [102] ) are further investigating this issue.

Conclusion

While multimodality therapy with surgery, chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy has proved successful for the management of locally advanced HNSCC, new treatment strategies are urgently needed for patients with recurrent and/or metastatic disease. Cetuximab is the first EGFR-targeted agent to demonstrate OS benefits in combination with radiation or chemotherapy [8,12], and has thus become a part of the current standard of care for HNSCC. However, cetuximab is associated with considerable adverse events, requires intravenous administration, and efficacy may be limited by primary and acquired resistance mechanisms. Newer anti-EGFR mAbs, as well as multitargeted and/or irreversible TKIs are being actively evaluated in clinical studies, and results from these trials may provide greater insight into the distinct role of these agents in the management of HNSCC. Moreover, validated biomarkers are urgently needed to predict treatment activity and resistance to anti-EGFR-targeted agents.

Expert commentary

While antibody-based therapy such as cetuximab will continue to be used in the primary treatment of HNSCC, oral TKIs are expected to be used in the maintenance setting. Investigational TKIs may provide several theoretical advantages over mAbs, including oral administration, irreversible inhibition of tyrosine kinase, inhibition of the intracellular tyrosine kinase domain in the presence of EGFRvIII, inhibition of other ErbB family receptors and lack of infusion reaction, while it lacks the potential advantage of the anti-tumor activity through ADCC that is associated with mAbs. In addition, TKIs and mAbs have a different toxicity profiles. The most common adverse events with TKIs are diarrhea and skin-related reactions, while skin-related reactions, hypomagnesimia and infusion reactions are common with mAbs. Data from randomized controlled trials are needed to better characterize the clinical efficacy and expected toxicities of newer multitargeted and/or irreversible TKIs, and the concept of adjuvant or maintenance treatment with these agents also requires further investigation.

Five-year view

During the next 5 years, it is expected that oncologists will select patients who will benefit most from EGFR inhibitor therapies for HNSCC based on validated biomarkers. We will also understand the anti-tumor activity through the immune system using mAbs. We hope to be able to further delineate who will benefit from antibody-based therapy versus small molecule TKI therapy within the group of patients who will benefit the most from EGFR inhibitor therapy. Moreover, the use of TKIs will allow for easier maintenance therapy for HNSCC, potentially as observed in estrogen receptor inhibitors in breast cancer.

Key issues.

Multimodal therapy with surgery, chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy has improved survival for locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), but new treatment strategies are urgently needed for patients with recurrent and/or metastatic disease.

In recent years, the EGF receptor (EGFR) has emerged as a rational therapeutic target for HNSCC.

Cetuximab is the first and only EGFR-targeted agent to date to demonstrate a survival benefit for patients with recurrent or metastatic HNSCC and has become part of the current standard of care.

However, cetuximab is associated with specific adverse events, requires intravenous administration and efficacy may be limited by primary and acquired resistance mechanisms.

Clinical studies are actively investigating newer anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies (e.g., panitumumab and zalutumumab) as well as investigational reversible and irreversible ErbB family tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g., lapatinib, afatinib and dacomitinib) to provide greater insight into the distinct role of these agents in the management of HNSCC.

Validated biomarkers are increasingly needed to more accurately predict clinical benefit and resistance to anti-EGFR therapy for the management of HNSCC.

Ongoing trials are also evaluating the potential impact of human papillomavirus status in the development of EGFR-targeted therapy for HNSCC.

Acknowledgments

C Chung has received research funding from AstraZeneca, Lilly Oncology and Bayer, and honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim and Merck for educational lectures and serving on ad hoc scientific advisory boards. This work was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals (BIPI).

Editorial support was provided by Staci Heise, PhD of MedErgy, which was contracted by BIPI for these services.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

A Markovic has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose. The authors meet criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, were fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions and were involved at all stages of manuscript development. The authors received no compensation related to the development of the manuscript. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

• of interest

•• of considerable interest

- 1.Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2011: the impact of eliminating socioeconomic and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2011;61(4):212–236. doi: 10.3322/caac.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hashibe M, Brennan P, Benhamou S, et al. Alcohol drinking in never users of tobacco, cigarette smoking in never drinkers, and the risk of head and neck cancer: pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(10):777–789. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hashibe M, Brennan P, Chuang SC, et al. Interaction between tobacco and alcohol use and the risk of head and neck cancer: pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(2):541–550. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. D’Souza G, Kreimer AR, Viscidi R, et al. Case–control study of human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;356(19):1944–1956. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065497. •• First study to firmly establish the causal relationship between HPV infection and development of oropharyngeal cancer

- 5.Bernier J, Domenge C, Ozsahin M, et al. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Trial 22931. Postoperative irradiation with or without concomitant chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer. N. Engl J. Med. 2004;350(19):1945–1952. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooper JS, Pajak TF, Forastiere AA, et al. Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 9501/Intergroup. Postoperative concurrent radiotherapy and chemotherapy for high-risk squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004;350(19):1937–1944. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Forastiere AA, Goepfert H, Maor M, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy for organ preservation in advanced laryngeal cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;349(22):2091–2098. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031317. •• First study to firmly establish the role of concurrent chemoradiotherapy in organ preservation setting without compromise in survival

- 8. Vermorken JB, Mesia R, Rivera F, et al. Platinum-based chemotherapy plus cetuximab in head and neck cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;359(11):1116–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802656. • First study to show a survival benefit of cetuximab given with platinum-based chemotherapy compared with chemotherapy alone in recurrent/ metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- 9.Ang KK, Berkey BA, Tu X, et al. Impact of epidermal growth factor receptor expression on survival and pattern of relapse in patients with advanced head and neck carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2002;62(24):7350–7356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung CH, Zhang Q, Hammond EM, et al. Integrating epidermal growth factor receptor assay with clinical parameters improves risk classification for relapse and survival in head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2011;81(2):331–338. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N. Engl.J. Med. 2010;363(1):24–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912217. •• Phase III data showing favorable prognosis in HPV-positive patients compared with HPV-negative patients

- 12.Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354(6):567–578. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar B, Cordell KG, Lee JS, et al. EGFR, p16, HPV Titer, Bcl-xL and p53, sex, and smoking as indicators of response to therapy and survival in oropharyngeal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26(19):3128–3137. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.7662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bianco R, Gelardi T, Damiano V, Ciardiello F, Tortora G. Rational bases for the development of EGFR inhibitors for cancer treatment. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007;39(7–8):1416–1431. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris RC, Chung E, Coffey RJ. EGF receptor ligands. Exp. Cell Res. 2003;284(1):2–13. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00105-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arteaga CL, Baselga J. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors: why does the current process of clinical development not apply to them? Cancer Cell. 2004;5(6):525–531. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galer CE, Corey CL, Wang Z, et al. Dual inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor and insulin-like growth factor receptor I: reduction of angiogenesis and tumor growth in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck. 2011;33(2):189–198. doi: 10.1002/hed.21419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316(5827):1039–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rubin Grandis J, Melhem MF, Gooding WE, et al. Levels of TGF-alpha and EGFR protein in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and patient survival. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90(11):824–832. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.11.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grandis JR, Tweardy DJ. Elevated levels of transforming growth factor alpha and epidermal growth factor receptor messenger RNA are early markers of carcinogenesis in head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 1993;53(15):3579–3584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung CH, Ely K, McGavran L, et al. Increased epidermal growth factor receptor gene copy number is associated with poor prognosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;24(25):4170–4176. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.2587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen EE, Lingen MW, Martin LE, et al. Response of some head and neck cancers to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors may be linked to mutation of ERBB2 rather than EGFR. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11(22):8105–8108. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee JW, Soung YH, Kim SY, et al. Somatic mutations of EGFR gene in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11(8):2879–2882. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinelli E, De Palma R, Orditura M, De Vita F, Ciardiello F. Anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibodies in cancer therapy. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2009;158(1):1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03992.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Britten CD. Targeting ErbB receptor signaling: a pan-ErbB approach to cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2004;3(10):1335–1342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang X, Gureasko J, Shen K, Cole PA, Kuriyan J. An allosteric mechanism for activation of the kinase domain of epidermal growth factor receptor. Cell. 2006;125(6):1137–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li S, Schmitz KR, Jeffrey PD, Wiltzius JJ, Kussie P, Ferguson KM. Structural basis for inhibition of the epidermal growth factor receptor by cetuximab. Cancer Cell. 2005;7(4):301–311. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.López-Albaitero A, Ferris RL. Immune activation by epidermal growth factor receptor specific monoclonal antibody therapy for head and neck cancer. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2007;133(12):1277–1281. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.12.1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurai J, Chikumi H, Hashimoto K, et al. Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity mediated by cetuximab against lung cancer cell lines. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007;13(5):1552–1561. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vermorken JB, Trigo J, Hitt R, et al. Open-label, uncontrolled, multicenter Phase II study to evaluate the efficacy and toxicity of cetuximab as a single agent in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck who failed to respond to platinum-based therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25(16):2171–2177. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rowan K. Should cetuximab replace cisplatin in head and neck cancer? J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(2):74–76. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp531. 78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tejani MA, Cohen RB, Mehra R. The contribution of cetuximab in the treatment of recurrent and/or metastatic head and neck cancer. Biologics. 2010;4:173–185. doi: 10.2147/btt.s3050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin NV, Pacifico V, Lai SE, et al. Management of rash to erlotinib (E) and cetuximab (C): results from the SERIES (Skin and Eye Reactions to Inhibitors of EGFR and kinases) clinic algorithm. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25(18 Suppl.) Abstract 19556. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stewart JS, Cohen EE, Licitra L, et al. Phase II study of gefitinib compared with intravenous methotrexate for recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck [corrected] J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27(11):1864–1871. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.0530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Licitra L, Mesia R, Rivera F, et al. Evaluation of EGFR gene copy number as a predictive biomarker for the efficacy of cetuximab in combination with chemotherapy in the first-line treatment of recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: EXTREME study. Ann. Oncol. 2011;22(5):1078–1087. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen EE, Kane MA, List MA, et al. Phase II trial of gefitinib 250 mg daily in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11(23):8418–8424. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burtness B, Goldwasser MA, Flood W, Mattar B, Forastiere AA. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Phase III randomized trial of cisplatin plus placebo compared with cisplatin plus cetuximab in metastatic/recurrent head and neck cancer: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23(34):8646–8654. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.4646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sok JC, Coppelli FM, Thomas SM, et al. Mutant epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFRvIII) contributes to head and neck cancer growth and resistance to EGFR targeting. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006;12(17):5064–5073. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bigner SH, Humphrey PA, Wong AJ, et al. Characterization of the epidermal growth factor receptor in human glioma cell lines and xenografts. Cancer Res. 1990;50(24):8017–8022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sugawa N, Ekstrand AJ, James CD, Collins VP. Identical splicing of aberrant epidermal growth factor receptor transcripts from amplified rearranged genes in human glioblastomas. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87(21):8602–8606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen LF, Cohen EE, Grandis JR. New strategies in head and neck cancer: understanding resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010;16(9):2489–2495. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jutten B, Dubois L, Li Y, et al. Binding of cetuximab to the EGFRvIII deletion mutant and its biological consequences in malignant glioma cells. Radiother. Oncol. 2009;92(3):393–398. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wheeler SE, Suzuki S, Thomas SM, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor variant III mediates head and neck cancer cell invasion via STAT3 activation. Oncogene. 2010;29(37):5135–5145. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wheeler DL, Huang S, Kruser TJ, et al. Mechanisms of acquired resistance to cetuximab: role of HER (ErbB) family members. Oncogene. 2008;27(28):3944–3956. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brand TM, Iida M, Wheeler DL. Molecular mechanisms of resistance to the EGFR monoclonal antibody cetuximab. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2011;11(9):777–792. doi: 10.4161/cbt.11.9.15050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yonesaka K, Zejnullahu K, Okamoto I, et al. Activation of ERBB2 signaling causes resistance to the EGFR-directed therapeutic antibody cetuximab. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011;3(99) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002442. 99ra86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dempke WC, Heinemann V. Resistance to EGF-R (erbB-1) and VEGF-R modulating agents. Eur. J. Cancer. 2009;45(7):1117–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Almendro V, García-Recio S, Gascón P. Tyrosine kinase receptor transactivation associated to G protein-coupled receptors. Curr. Drug Targets. 2010;11(9):1169–1180. doi: 10.2174/138945010792006807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frederick BA, Helfrich BA, Coldren CD, et al. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition predicts gefitinib resistance in cell lines of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and non-small cell lung carcinoma. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2007;6(6):1683–1691. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Holz C, Niehr F, Boyko M, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal-transition induced by EGFR activation interferes with cell migration and response to irradiation and cetuximab in head and neck cancer cells. Radiother. Oncol. 2011;101(1):158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Basu D, Nguyen TT, Montone KT, et al. Evidence for mesenchymal-like sub-populations within squamous cell carcinomas possessing chemoresistance and phenotypic plasticity. Oncogene. 2010;29(29):4170–4182. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Skvortsova I, Skvortsov S, Raju U, et al. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and c-myc expression are the determinants of cetuximab-induced enhancement of squamous cell carcinoma radioresponse. Radiother. Oncol. 2010;96(1):108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saadeh CE, Lee HS. Panitumumab: a fully human monoclonal antibody with activity in metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann. Pharmacother. 2007;41(4):606–613. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rischin D, Spigel DR, Adkins D, et al. Panitumumab (pmab) regimen in second-line monotherapy (PRISM) in patients (pts) with recurrent (R) or metastatic (M) squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN): interim safety analysis. Ann. Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl. 8) Abstract 1036P. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vermorken JB, Stohlmacher J, Davidenko I, et al. Primary efficacy and safety results of SPECTRUM, a Phase 3 trial in patients (pts) with recurrent and/or metastatic (R/M) squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN) receiving chemotherapy with or without panitumumab (pmab) Ann. Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl. 8) Abstract LBA26. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Patel D, Guo X, Ng S, et al. IgG isotype, glycosylation, and EGFR expression determine the induction of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in vitro by cetuximab. Hum. Antibodies. 2010;19(4):89–99. doi: 10.3233/HAB-2010-0232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schneider-Merck T, Trepel M. Lapatinib. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2010;184:45–59. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-01222-8_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Desjarlais JR, Lazar GA, Zhukovsky EA, Chu SY. Optimizing engagement of the immune system by anti-tumor antibodies: an engineer’s perspective. Drug Discov. Today. 2007;12(21–22):898–910. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Machiels JP, Subramanian S, Ruzsa A, et al. Zalutumumab plus best supportive care versus best supportive care alone in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck after failure of platinum-based chemotherapy: an open-label, randomised Phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(4):333–343. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cohen MH, Williams GA, Sridhara R, Chen G, Pazdur R. FDA drug approval summary: gefitinib (ZD1839) (Iressa) tablets. Oncologist. 2003;8(4):303–306. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.8-4-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Soulieres D, Senzer NN, Vokes EE, Hidalgo M, Agarwala SS, Siu LL. Multicenter Phase II study of erlotinib, an oral epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous cell cancer of the head and neck. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004;22(1):77–85. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cohen EE, Rosen F, Stadler WM, et al. Phase II trial of ZD1839 in recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003;21(10):1980–1987. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kondo N, Tsukuda M, Ishiguro Y, et al. Antitumor effects of lapatinib (GW572016), a dual inhibitor of EGFR and HER-2, in combination with cisplatin or paclitaxel on head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2010;23(4):957–963. doi: 10.3892/or_00000720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Harrington KJ, Berrier A, Robinson M, et al. Phase II study of oral lapatinib, a dual-tyrosine kinase inhibitor, combined with chemoradiotherapy (CRT) in patients (pts) with locally advanced, unresected squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN) J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28(15S) Abstract 5505. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Del Campo JM, Hitt R, Sebastian P, et al. Effects of lapatinib monotherapy: results of a randomised Phase II study in therapy-naive patients with locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Br. J. Cancer. 2011;105(5):618–627. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.de Souza JA, Davis DW, Zhang Y, et al. A Phase II study of lapatinib in recurrent/ metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012;18(8):2336–2343. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Harrington KJ, Berrier A, Robinson M, et al. Phase II study of oral lapatinib, a dual-tyrosine kinase inhibitor, combined with chemoradiotherapy (CRT) in patients (pts) with locally advanced, unresected squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN). Chicago, IL, USA. Presented at: 46th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology; Jun, 2010. pp. 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li D, Ambrogio L, Shimamura T, et al. BIBW2992, an irreversible EGFR/HER2 inhibitor highly effective in preclinical lung cancer models. Oncogene. 2008;27(34):4702–4711. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yamamoto N, Katakami N, Atagi S, et al. A Phase II trial of afatinib (BIBW 2992) in patients (pts) with advanced non-small cell lung cancer previously treated with erlotinib or gefitinib [abstract 7524]. Chicago, IL, USA. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology; Jun, 2011. pp. 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yap TA, Vidal L, Adam J, et al. Phase I trial of the irreversible EGFR and HER2 kinase inhibitor BIBW 2992 in patients with advanced solid tumors. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28(25):3965–3972. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Seiwert TY, Fayette J, DelCampo JM, et al. A randomized, open-label, Phase II study of afatinib (BIBW 2992) versus cetuximab in recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck [abstract PP3.4]. Rome, Italy. Presented at: Proceedings of the 3rd Trends in Head and Neck Oncology; Nov, 2011. pp. 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Gale CM, et al. PF00299804, an irreversible pan-ERBB inhibitor, is effective in lung cancer models with EGFR and ERBB2 mutations that are resistant to gefitinib. Cancer Res. 2007;67(24):11924–11932. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jänne PA, Boss DS, Camidge DR, et al. Phase I dose-escalation study of the pan-HER inhibitor, PF299804, in patients with advanced malignant solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011;17(5):1131–1139. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Siu LL, Hotte SJ, Laurie SA, et al. Phase II trial of the irreversible oral pan-human EGF receptor (HER) inhibitor PF-00299804 (PF) as first-line treatment in recurrent and/or metastatic (RM) squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN) J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29 doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds503. Abstract 5561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fakhry C, Westra WH, Li S, et al. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(4):261–269. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Worden FP, Kumar B, Lee JS, et al. Chemoselection as a strategy for organ preservation in advanced oropharynx cancer: response and survival positively associated with HPV16 copy number. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26(19):3138–3146. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.7597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lassen P, Eriksen JG, Hamilton-Dutoit S, Tramm T, Alsner J, Overgaard J. Effect of HPV-associated p16INK4A expression on response to radiotherapy and survival in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27(12):1992–1998. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hong A, Dobbins T, Lee CS, et al. Relationships between epidermal growth factor receptor expression and human papillomavirus status as markers of prognosis in oropharyngeal cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 2010;46(11):2088–2096. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chau NG, Perez-Ordonez B, Zhang K, et al. The association between EGFR variant III, HPV, p16, c-MET, EGFR gene copy number and response to EGFR inhibitors in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck Oncol. 2011;3:11. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-3-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Psyrri A, Ghebremichael MS, Pectasides E, et al. p16 protein status and response to treatment in a prospective clinical trial (ECOG 2303) of patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:e16032. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pajares B, Trigo Perez JM, Toledo MD, et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV)-related head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) and outcome after treatment with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors (EGFR inhib) plus radiotherapy (RT) versus conventional chemotherapy (CT) plus RT. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:5528. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Thomas F, Rochaix P, Benlyazid A, et al. Pilot study of neoadjuvant treatment with erlotinib in nonmetastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007;13(23):7086–7092. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chua DT, Wei WI, Wong MP, Sham JS, Nicholls J, Au GK. Phase II study of geftinib for the treatment of recurrent and metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck. 2008;30(7):863–867. doi: 10.1002/hed.20792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ma B, Hui EP, King A, et al. A Phase II study of patients with metastatic or locoregionally recurrent nasopharyngeal carcinoma and evaluation of plasma Epstein-Barr virus DNA as a biomarker of efficacy. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2008;62(1):59–64. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0575-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Websites

- 101.ERBITUX® (cetuximab) injection, for intravenous infusion [package insert]. Distributed and marketed by Bristol-Myers Squibb Company. Princeton, NJ: Co-marketed by Eli Lilly and Company, IN, USA; 2010. http://packa~einserts.bms.com/pi/pierbitux.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 102.ClinicalTrials.gov. www.clinicaltrials.gov.

- 103.Vectibix® (panitumumab) injection for intravenous use [package insert] CA, USA: Amgen, Inc.; 2008. http://pi.arngen.com/unitedstates/vectibix/vectibixpi.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 104.TYKERB® (lapatinib) tablets [package insert] USA: GlaxoSmithKline, NC; http://us.gsk.com/products/assets/ustykerb.pdf. [Google Scholar]