Abstract

d-Propranolol (d-Pro: 2–8 mg·(kg body mass)−1·day−1) protected against cardiac dysfunction and oxidative stress during 3–5 weeks of iron overload (2 mg Fe–dextran·(g body mass)−1·week−1) in Sprague–Dawley rats. At 3 weeks, hearts were perfused in working mode to obtain baseline function; red blood cell glutathione, plasma 8-isoprostane, neutrophil basal superoxide production, lysosomal-derived plasma N-acetyl-β-galactosaminidase (NAGA) activity, ventricular iron content, and cardiac iron deposition were assessed. Hearts from the Fe-treated group of rats exhibited lower cardiac work (26%) and output (CO, 24%); end-diastolic pressure rose 1.8-fold. Further, glutathione levels increased 2-fold, isoprostane levels increased 2.5-fold, neutrophil superoxide increased 3-fold, NAGA increased 4-fold, ventricular Fe increased 4.9-fold; and substantial atrial and ventricular Fe-deposition occurred. d-Pro (8 mg) restored heart function to the control levels, protected against oxidative stress, and decreased cardiac Fe levels. After 5 weeks of Fe treatment, echocardiography revealed that the following were depressed: percent fractional shortening (%FS, 31% lower); left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (LVEF, 17%), CO (25%); and aortic pressure maximum (Pmax, 24%). Mitral valve E/A declined by 18%, indicating diastolic dysfunction. Cardiac CD11b+ infiltrates were elevated. Low d-Pro (2 mg) provided modest protection, whereas 4–8 mg greatly improved LVEF (54%–75%), %FS (51%–81%), CO (43%–78%), Pmax (56%–100%), and E/A >100%; 8 mg decreased cardiac inflammation. Since d-Pro is an antioxidant and reduces cardiac Fe uptake as well as inflammation, these properties may preserve cardiac function during Fe overload.

Keywords: iron overload, d-propranolol, echocardiography, oxidative stress, cardiac dysfunction

Introduction

Iron overload may occur as a primary genetic disorder or secondary to other disorders that involve excessive intake or release of iron. Clinical hemochromatosis is typified by excessive iron deposition in various tissues, including liver, kidney, and heart, and has been linked to endocrinopathies (diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, hypogonadism, etc.), cirrhosis, and heart failure (Giardina and Grady 1995; Hershko et al. 1998; for review, Murphy and Oudit 2010). Iron overload remains a serious complication for patients receiving blood cardioplegia (cardiopulmonary bypass procedures) (Pepper et al. 1995) or multiple transfusions (anemia) as part of normal therapy (Jensen et al. 1997; Mariotti et al. 1998). Indeed, cardiac disease is the principle cause of death in transfused β-thalassaemia patients (Kremastinos et al. 1995; Lombardo et al. 1995).

Excessive iron has been linked to enhanced tissue injury through oxidative stress mechanisms (Bacon et al. 1983; Masini et al. 1986; Gunther et al. 1992). Transition metals, like iron, can catalytically transform (via the Haber–Weiss and Fenton-type reactions) less toxic oxygen species such as superoxide anion and hydrogen peroxide, to the more pro-oxidant hydroxyl radical (Halliwell and Gutteridge 1986; Kramer et al. 2000). Iron can also transform the less toxic lipid hydroperoxides to the more pro-oxidant peroxyl and alkoxyl free radicals (Kramer et al. 1994). These pro-oxidant species can initiate, and in some cases propagate, lipid peroxidation leading to tissue damage (van der Kraaij et al. 1988; Kramer et al. 2000). Moreover, oxidative injury resulting from secondary stresses (malnutrition, inflammation, HIV-1, or cardiovascular diseases) may be amplified in the presence of a co-existing iron-overload condition (Kramer et al. 2006).

Since there is no regulated physiological mechanism for iron excretion in humans (Giardina and Grady 1995), use of metal chelators is a common treatment to decrease toxicity secondary to iron overload (Pepper et al. 1995; Politi et al. 1995; Eaton and Qian 2002; Gujja et al. 2010). Iron chelation therapy using deferoxamine (trihydroxamic acid, Desferal™ or DFO), has decreased the morbidity and mortality found in compliant transfused patients (Giardina and Grady 1995; Jensen et al. 1997). However, concerns have emerged regarding its clinical use (Giardina and Grady 1995) as well as safety issues (Jensen et al. 1997). DFO is poorly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract and must be administered parenterally; the discomfort during administration and other side effects contribute to noncompliance (Gujja et al. 2010). Efforts directed towards development of alternative, safe oral chelators have been pursued (Kontoghiorghes 1995; Delea et al. 2007; Vichinsky 2008; Taher and Cappellini 2009).

The combined use of DFO chelation with classic antioxidants (ascorbic acid, β-carotene, or vitamin E, with or without selenium) have shown promise as protective therapies (Giardina and Grady 1995; Whittaker et al. 1996; Jensen et al. 1997; Bartfay et al. 1998; Hershko et al. 1998). Furthermore, certain cardioactive agents also have antioxidant properties and may afford additional cardiovascular protection during chelation therapy of iron-overloaded individuals. We (Kramer et al. 1994) have previously reported that d-propranolol (d-Pro), the inactive isomer of the β-adrenergic receptor blocker, is a relatively potent membrane anti-peroxidative agent (l- and d- isomers were equipotent), which afforded cardioprotection to oxidatively-stressed (ischemia/reperfused) rat hearts and adult canine cardiomyocytes. We (Kramer et al. 2006) also presented evidence that d-Pro's beneficial effects may involve its lysosomal stabilizing effects, as well as its ability to modify iron status in hearts from iron-loaded rats. In the present study, we demonstrate for the first time that in vivo chronic d-Pro treatment dose-dependently protects against iron-overload-induced oxidative stress in rats and improves myocardial function, as monitored ex vivo using the isolated perfused working heart model, as well as in situ by non-invasive echocardiography.

Material and methods

Chemicals

All dry chemicals and solvents were from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA) or Sigma Chemicals (St. Louis, Missouri, USA). Iron–dextran solution (100 mg iron·mL−1) and d-Pro (hydrogen chloride form) were from Sigma Chemicals. Buffers and assay solutions were prepared with deionized, double-distilled water, and the level of trace metals (atomic absorption spectroscopy; Shimadzu AA-6200; Columbia, Maryland, USA) were below the limits of detection.

Animal assurance

All animal experiments were guided by The Principles of Care and Use of Laboratory Animals recommended by the US Department of Health and Human Services and approved by The George Washington University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Iron and d-propranolol treatment of animals

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (300 g) were maintained on a commercially available nutritionally balanced Harlan-Teklad diet (Madison, Wisconsin, USA: contained 42 ppm Fe) and had free access to deionized, distilled drinking water. Gross changes in animal body mass, eating habits, or behavior were not observed using the iron–dextran loading protocol (Kramer et al. 2006), and iron loading (tissue, plasma) was verified by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Anesthetized rats (2% isoflurane via inhalation chamber; EZ Anesthesia, Palmer, Penn.) received biweekly intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections totaling 2 mg iron–dextran·(g body mass)−1·week−1 or equal injection volumes of 10% Na–dextran (controls) for 3 to 5 weeks. Some rats subjected to the iron (or sodium)–dextran loading protocol also received d-Pro (or placebo) concurrently, as continuous-release subcutaneous pellets (Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, Florida, USA) delivering 2, 4, or 8 mg·(kg body mass)−1·day−1 during the experimental period.

Isolated perfused working heart model

In some studies, ex vivo heart function values during normal perfusion were obtained after 3 weeks using the isolated-perfused working heart model (Kramer et al. 2006). Hearts (non-paced) from anesthetized (2% isoflurane) rats were cannulated by the aorta (afterload = 80 mm Hg (1 mm Hg = 133.322 Pa)) to a working heart perfusion apparatus within 45 s of excision, and were then converted to working mode perfusion by cannulating the left pulmonary vein (preload = 10 mm Hg). Hearts were then exposed to 30 min nonrecirculating stabilization (control) perfusion with physiologic Krebs–Henseleit buffer (KHB; gassed with a mixture of 95% O2 : 5% CO2 v/v, pH 7.4, 37 °C) containing 1.25 mmol·L−1 CaCl2 and 10.0 mmol·L−1 glucose; baseline functional / hemodynamic parameters were taken at the end of this period. Coronary flow rate, aortic output, and pressure indices (Statham Gb transducer for left ventricular systolic [LVSP] and end-diastolic [LVEDP] pressures) were monitored during perfusion. Cardiac pressure–volume work ([aortic output + coronary flow] × LVSP) was assessed as a functional index.

Non-invasive echocardiography

In other studies, animals were subjected to the same iron loading protocol but for a more prolonged treatment period of up to 5 weeks, and in situ cardiac function was monitored periodically by non-invasive echocardiography. A GE VingMed System Five Echocardiogram with a 10 MHz probe was used to image hearts. Echocardiography (Kramer et al. 2009) was performed on anesthetized (2% isoflurane with 100% O2) rats, and heart rate and rectal temperature were monitored. Rats were placed on a heated platform with paws taped to electrode pads for monitoring. Ambient temperature was heat lamp-controlled. Hair was removed from the thorax and rats were imaged for 30 min and placed in 100% O2 until recovered. An image depth of 3 cm was used. Two-dimensional, M-mode, and pulsed Doppler images were obtained and measurements were performed. Measured parameters include aortic and pulmonary artery diameters to help calculate stroke volumes; left ventricular (LV) wall thickness and internal diameters to detect a dilated or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; LV internal diameters in systole and diastole to calculate shortening fraction (clinical assessment of cardiac function); and spectral Doppler velocities for the pulmonic and aortic outflows to calculate cardiac output and for mitral valve inflows (E and A waves) to assess ventricular diastolic function.

Iron determinations

After 3 weeks of treatment, plasma iron content was assessed by flame emission atomic absorption spectroscopy using acidified diluted samples (1:10 in trace metal grade 0.5 N HNO3). Tissue iron content was assessed after acid–heat destruction of ventricular tissue and aliquot dilution. Each value was an average of 6 separate readings. Perls' Prussian blue staining for trivalent iron (Luna 1968) and counter-staining with fast red, was used to reveal iron deposits in atrial and ventricular tissues (5 μm thick sections).

Red blood cell glutathione

After 3 weeks of treatment, red blood cells were centrifuged (200g, 10 min), and total glutathione (GSH) + 1/2 oxidized GSH (GSSG)) and GSSG levels were determined as a systemic oxidative stress index using the previously described enzymatic recycling method (Mak and Weglicki 1994; Mak et al. 1996). Typically, the level of GSSG represents < 3% of the total glutathione for control samples.

Plasma 8-isoprostane levels

After 3 weeks of treatment, the lipid peroxidation marker, 8-isoprostane (1 mL sample), was determined by a colorimetric ELISA kit (Cayman Chemical, Michigan, USA).

Circulating neutrophil superoxide production

After 3 weeks of treatment, basal superoxide formation by primed neutrophils (PMNs) was determined by cytochrome c reduction (Mak et al. 2008). PMNs were obtained from the whole blood using a modified ficoll hypaque reagent, which is a step-gradient. PMNs were recovered from the lower band, and washed. The resulting PMN fraction was found to have >90% purity. Basal superoxide production was assayed in the neutrophil suspensions (0.5–0.75 × 106 cells·mL−1 of Krebs–Ringer phosphate buffer containing 5 mmol·L−1 glucose, 1 mmol·L−1 CaCl2, 1 mmol·L−1 MgCl2, pH 7.6) plus 75 μmol/L cytochrome c ± 50 μg superoxide dismutase (SOD). After 20 min incubation (30 °C), samples were immersed in an ice-bath and centrifuged at 600g for 5 min at 4 °C; superoxide production was estimated as SOD-inhibitable reduction of cytochrome c in the supernatant using the extinction coefficient: E550 = 2.1 × 104 mol·L−1·cm−1.

Tissue inflammation

After 5 weeks of treatment, cardiac atrial and ventricular tissues were rapidly excised, rinsed, quickly embedded in OCT compound, and stored at −70 °C. Cryo-sections (5 μm thickness) were visualized by indirect immunohistochemical staining for CD11b+ cell infiltrates using goat anti-rat CD11b antibody (1:250, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Paso Robles, California) and Vectastain Elite ABC immunoperoxidase system and Immpact VIP peroxidase substrate kits (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, Calif.) (Mak et al. 2009). Negative controls (primary antibody omitted) were included in all experiments. Samples were examined with an Olympus BX60 microscope and images were taken with a digital camera (Evolution Colour MP; Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, Md.).

Plasma N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase (NAGA) activity

After 3 weeks of treatment, plasma samples (50 μL) were assayed for NAGA activity (tissue-derived lysosomal acid hydrolase) using our spectrocolorimetric (410 nm) procedure (Mak et al. 1983; Kramer et al. 2006).

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for statistical comparison of several means and the Tukey's test for all paired mean comparisons. Values for p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

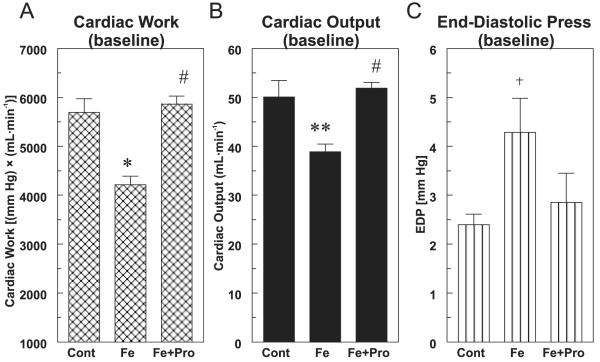

Rats receiving 2 mg Fe–dextran·g−1·week−1 (i.p.) for 3 weeks exhibited significant hemodynamic depression when normally perfused in working heart mode. Hearts from these rats exhibited significant reductions in cardiac pressure–volume work (Fig. 1A, 26% lower, p < 0.01), and much of this loss could be attributed to depression of cardiac output (Fig. 1B, 24% lower, p < 0.02). In addition, a 1.8-fold elevation in end-diastolic pressure was observed (Fig. 1C, p < 0.05). Concurrent treatment with high dose (8 mg·kg−1·day−1) d-Pro restored these parameters to control levels.

Fig. 1.

Effect of chronic d-propranolol treatment (Pro; 8 mg·(kg body mass)−1·day−1, subcutaneous pellet) on (A) cardiac pressure–volume work, (B) cardiac output, and (C) end-diastolic pressure of normally perfused hearts from 3-week iron-overloaded (Fe; 2 mg·g−1·week−1) rats. Hearts were subjected to working heart perfusion under physiological conditions for 30 min using Krebs–Henseleit buffer. Values are the mean ± SE of 5–6 hearts; +, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.02; and *, p < 0.01 compared with the control;#, p < 0.001 compared with Fe alone. Cont, control.

We examined RBC glutathione status after 3 weeks, and found that while total RBC glutathione levels (GSH + GSSG) displayed no significant changes (not shown), GSSG levels were significantly higher (>2-fold, p < 0.05) in Fe-loaded rats, indicative of greater antioxidant consumption (Fig. 2A). Low dose (2 mg·kg−1·day−1) d-Pro nonsignificantly lowered GSSG, and high dose (8 mg) significantly (p < 0.05) attenuated the Fe-induced change in RBC GSSG level. As a quantitative index of systemic oxidative stress, levels of F2-like isoprostanes derived from non-enzymatic peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids were determined by an 8-isoprostane enzyme immunoassay. As shown in Fig. 2B, Fe-overload alone induced a 2.5-fold higher level of 8-isoprostane after 3 weeks (p < 0.02); low (2 mg) d-Pro nonsignificantly decreased, and high (8 mg) d-Pro significantly (p < 0.05) lowered 8-isoprostane levels.

Fig. 2.

Effects of iron-overload (Fe) on rat (A) red blood cell (RBC) oxidized glutathione (GSSG) levels, and (B) circulating 8-isoprostane content in the presence and absence of d-propranolol ((Lo Pro) 2 or (Hi Pro) 8 mg·(kg body mass)−1·day−1, subcutaneous pellet). Values for both parameters are the mean ± SE of 4–6 rats. Whole blood samples were obtained from rats at 3 weeks, and total and oxidized red blood cell glutathione levels were determined by the enzymatic cyclic method using glutathione reductase;+, p < 0.05 compared with the control (Cont); *, p < 0.05 compared with Fe alone. Plasma 8-isoprostane levels in 3 week treated rats were determined by enzyme immunoassay; **, p < 0.02 compared with the control;+, p < 0.05 compared with Fe alone.

Basal superoxide anion production by circulating neutrophils (PMNs) was examined after 3 weeks (Fig. 3A). Fe-overload alone promoted >3-fold higher levels (p < 0.05), suggesting that enhanced oxidative stress may derive from activated PMNs during Fe-overload. At the high d-Pro dose (8 mg), basal free radical activity was completely restored to control levels (p < 0.05). The Fe-loading group also displayed significant elevations (>4-fold; p < 0.01) in plasma lysosomal enzyme activity (NAGA) (Fig. 3B), suggesting that tissue injury had occurred after 3 weeks of Fe-treatment. d-Pro (8 mg) significantly decreased plasma NAGA activity (72%, p < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Effects of iron-overload (Fe) on rat (A) neutrophil basal superoxide production, and (B) plasma lysosomal N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase (NAGA) activity after 3 weeks, and the influence of d-propranolol (Hi Pro; 8 mg·(kg body mass)−1·day−1). Values for both parameters are the mean ± SE of 4–6 rats. Neutrophils from whole blood were isolated using a modified ficoll hypaque reagent (step-gradient), and basal superoxide production was determined by superoxide-dismutase (SOD)-inhibitable cytochrome c reduction;+, p < 0.05 compared with the control (Cont); *, p < 0.05 compared with Fe alone. Plasma samples were analyzed for NAGA activity using a spectrocolorimetric assay; **, p < 0.01 compared with the control;+, p < 0.05 compared with Fe alone; AU, arbitrary unit.

The iron-loading regimen led to an 18-fold increase (p < 0.02) in plasma iron levels after 3 weeks compared with the control. In association, we demonstrated an increase in cardiac ventricular tissue iron content (4.9-fold; p < 0.01) during Fe loading (Fig. 4). Ventricular Fe content was significantly reduced (35%, p < 0.05) by concurrent d-Pro treatment (8 mg) versus Fe alone. In addition, Perls' staining for trivalent iron in cardiac atrial (Fig. 5, lower panels) and ventricular (Fig. 5, upper panels) sections demonstrated that d-Pro (2 and 8 mg) can dose-dependently lessen tissue Fe deposition after 3 weeks of Fe-loading.

Fig. 4.

Ventricular tissue iron levels in 3 week iron–dextran loaded rats with or without d-propranolol (d-Pro; Hi Pro) treatment. Rats were treated with 2 mg Fe·(g body mass)−1·week−1 by intraperitoneal injection, or with Fe plus 8 mg d-Pro·kg−1·day−1 by subcutaneous pellet. Time-paired sodium–dextran controls were used for comparison. Values are the mean ± SE of 4–6 rats; *, p < 0.01 compared with the control (Cont);+, p < 0.05 compared with Fe alone.

Fig. 5.

Rat atrial (lower panels) and ventricular (upper panels) tissue sections (5 μm thick) after 3 weeks of iron (Fe) treatment with or without d-propranolol were stained using Perls' Prussian blue method for iron deposits (arrows (blue on Web site only)) and counter-stained with fast red. Differences in iron deposition are shown in tissues from the control, Fe alone, Fe plus low-dose (Low d-Pro, 2 mg·kg−1·day−1), and Fe plus high-dose (Hi d-Pro, 8 mg·(kg body mass)−1·day−1) d-Pro-treated groups. Magnification 40×.

Iron (Fe) overloading was extended to 5 weeks to assess oxidative/inflammatory stress, the progressive development of cardiac dysfunction in situ (echocardiography), and the potential dose-dependent benefits of concurrent d-Pro treatment (2, 4, or 8 mg·kg−1·day−1). Persistence of Fe-mediated oxidative stress at 5 weeks was confirmed by the presence of heightened plasma 8-isoprostane levels (2.6-fold versus the control) and enhanced PMN basal superoxide production (3.2-fold). Fe loading for 5 weeks also led to substantial tissue inflammation (Fig. 6, CD11b+ infiltrates) in atria (high density in pericardium) and ventricles (diffuse and perivascular localization), and this was attenuated by d-Pro treatment (8 mg·kg−1·day−1). Echocardiography was performed on anesthetized rats prior to (baseline measurements) and during (1.5, 3, and 5 weeks) Fe-treatment. Compared with time-matched controls, Fe treatment alone progressively decreased cardiac systolic function (Fig. 7A, percent fractional shortening [%FS]: 18%, 25%, 31% lower; Fig. 7B, LV ejection fraction [LVEF]:12%, 15%, 17% lower), decreased cardiac output (Fig. 8A, CO: 12.5%, 15%, 25% lower), and lowered aortic pressure maximum (Fig. 8B, Pmax: 11%, 19%, 24% lower) at 1.5, 3, and 5 weeks, respectively. Dimensions of the LV posterior wall in systole (LVPWs; Fig. 9A, 19%–25%) and inter-ventricular septum in systole (IVSs; Fig. 9B, 14%–23%) decreased, indicating that critical anatomical parameters were also impacted by Fe. No significant differences in heart rate were observed in any treatment groups versus control. A progressive decline (14% and 18%) in the mitral valve E/A wave ratio did occur (Fig. 7C) at 3 and 5 weeks, respectively, indicating modest diastolic dysfunction during this period. d-Pro treatment (4 and 8 mg) provided dose-dependent protection against these Fe-mediated changes (Figs. 7–9). At 5 weeks (Figs. 10A–10D), the lowest dose of d-Pro (2 mg) was not effective against Fe-induced declines in cardiac output (C), aortic Pmax (not shown), or LVPWs (not shown), but did afford modest protection against losses in %FS (A: 33% improved compared with untreated Fe, nonsignificant), LVEF (B: 49% improved, p < 0.05), and mitral E/A (D: 43% improved, nonsignificant). The mid- (4 mg) and high (8 mg) doses improved the Fe-induced declines in %FS by 51% and 81% (A), in LVEF by 54% and 75% (B), in cardiac output by 43% and 78% (C), and in aortic Pmax by 56% and 100% (Fig. 8B), respectively. Moreover, the 4 and 8 mg doses completely prevented the significant decline in mitral value E/A (Fig. 10D), and substantially countered the deleterious impact of Fe on dimensions of key anatomical indices (Figs. 9A–9B).

Fig. 6.

Atrial (lower panels) and ventricular (upper panels) tissue sections (5 μm) from the 5 week control (Ctl, left panel), iron (Fe)-treated (middle panel), and Fe plus high (Hi d-Pro, 8 mg·(kg body mass)−1·day−1) d-propranolol (right panel) treated rats were stained immunohistochemically for CD11b[+] cell infiltrates. Negative controls (primary antibody omitted) were included in all immunohistochemistry experiments. Magnification 20×.

Fig. 7.

Effects of iron (Fe) overload and d-propranolol treatment on the progressive development of rat cardiac dysfunction as assessed by echocardiography. (A) Left ventricular shortening fraction (%FS), (B) left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and (C) mitral valve E/A ratio. Echocardiography was performed after 1.5, 3, and 5 weeks of Fe treatment (2 mg iron–dextran·(g body mass)−1·week−1, intraperitoneal injection) with or without concurrent d-propranolol (4 (Mid) or 8 (Hi) mg·kg−1·day−1, continuous release by subcutaneous pellet). Values are the mean ± SE of 4–6 rats; **, p < 0.05; #, p < 0.02; and *, p < 0.01 compared with the time-paired control; a, p < 0.5; b, p < 0.02; and c, p < 0.01 compared with Fe alone.

Fig. 8.

Effects of iron (Fe) overload and d-propranolol treatment on the progressive changes in rat heart hemodynamic parameters as assessed by echocardiography. (A) Cardiac output = cross-sectional area × velocity time integral × heart rate; and (B) aortic pressure maximum (Pmax). Echocardiography was performed after 1.5, 3, and 5 weeks of Fe treatment with or without concurrent d-propranolol (4 (Mid) or 8 (Hi) mg·(kg body mass)−1·day−1). Values are the mean ± SE of 4–6 rats; **, p < 0.05; #, p < 0.02 compared with the time-paired control; a, p < 0.5; b, p < 0.02 compared with Fe alone.

Fig. 9.

Effects of iron (Fe) overload and d-propranolol (Pro) treatment on the progressive changes in dimensions of rat heart. (A) Left ventricular posterior wall in systole (LVPWs); (B) interventricular septum in systole (IVSs). Echocardiography was performed after 1.5, 3, and 5 weeks of Fe treatment with or without concurrent d-propranolol (4 (Mid) or 8 (Hi) mg·(kg body mass)−1·day−1). Values are the mean ± SE of 4–6 rats; **, p < 0.05; #, p < 0.02; and *, p < 0.01 compared with the time-paired control; a, p < 0.5; b, p < 0.02; c, p < 0.01 compared with Fe alone.

Fig. 10.

Dose-dependent effects of d-propranolol (d-Pro) on left ventricular (LV) systolic function, cardiac output, and diastolic function after 5 weeks of Fe overload. (A) Percent of fractional shortening (%FS); (B) LV ejection fraction (LVEF); (C) cardiac output; and (D) mitral valve E/A wave ratio. Echocardiography was performed after 5 weeks of Fe treatment with or without concurrent d-Pro (2, 4, or 8 mg·(kg body mass)−1·day−1). Values for the d-Pro (8 mg) only treatments were not significantly different from the time-paired control. Values are the mean ± SE of 4–6 rats; **, p < 0.05; #, p < 0.02; and *, p < 0.01 compared with the time-paired control; a, p < 0.5; b, p < 0.02; and c, p < 0.01 compared with Fe alone.

Discussion

We (Kramer et al. 2000, 2006) and others (van der Kraaij et al. 1988) previously demonstrated that the extent of iron overload dictates the severity of oxidative stress, tissue injury, and contractile dysfunction in the rodent model. In our earlier studies, issues of hormonal and (or) neuronal regulation of cardiac function inherent in intact animals, were circumvented by employing the isolated perfused working rat heart model. We determined that low (<0.07 mg·g−1·week−1 for 3 weeks) (Kramer et al. 2000) to moderate (1.5 mg·g−1·week−1 for 3 weeks) (Kramer et al. 2006) iron-loading regimens failed to cause overt tissue injury or cardiac dysfunction during perfusion under normal condition, even though higher plasma iron content (8.1-fold) and in vivo oxidative stress (2.5-fold higher plasma conjugated diene levels) were evident with the moderate regimen. Nevertheless, both the low and moderate iron-loading regimens predisposed rat hearts to injury from secondary stresses, such as anoxia/reoxygenation (van der Kraaij et al. 1988) and ischemia/reperfusion (enhanced iron-catalyzed free radical production, tissue injury, and loss of contractile function) (Kramer et al. 2000, 2006).

In the current study, hearts from rats receiving a higher Fe-loading treatment (2 mg·g−1·week−1) exhibited early-onset (3 weeks) of cardiac dysfunction when perfused under normal physiological conditions. Cardiac pressure–volume work was significantly lower compared with the control, and this was largely due to reduced cardiac output, since LV systolic pressure was only mildly depressed (<7%). The significant rise in end-diastolic pressure suggested compromised relaxation and ventricular stiffening, and was consistent with early signs of LV diastolic dysfunction (Oudit et al. 2004).

We confirmed the pro-oxidant nature of iron (Kadiiska et al. 1995; Bartfay et al. 1998) by examining markers of systemic oxidative stress in 3 week Fe-overloaded (2 mg·g−1·week−1) rats. Short-term iron overload caused enhanced RBC glutathione consumption, a rise in lipid peroxidation products (8-isoprostane), a dramatic increase in basal superoxide production by circulating neutrophils, and heightened release of tissue-derived lysosomal NAGA into the plasma. In association, cardiac ventricular tissue iron content rose nearly 5-fold, and substantial iron deposits in atrial and ventricular tissue sections were apparent, especially in the perivascular areas. These observations are in general agreement with others (Voogd et al. 1992) who reported histological evidence that myocardial iron enrichment during early stages (<6 weeks) of Fe–dextran loading in rats occurred primarily within vascular pericytes and endothelial cell vesicles. Collectively, these findings are consistent with reports that Fe-overload-mediated free radical stress can lead to cellular dysfunction, altered excitation–contraction coupling, as well as electrophysiology and contractile dysfunction (Nakaya et al. 1987; Horackova et al. 2000; Schwartz et al. 2002; Folden et al. 2003).

Although l-propranolol's pharmacologic action as a β-adrenergic receptor blocker is well documented, it's antioxidant and lysosomotropic properties are not as well recognized (Kramer et al. 1994, 2000, 2006; Mak et al. 2006). We have previously shown that both the l (active blocker) and d (inactive) stereoisomer's of propranolol were equally potent as membrane chain breaking antioxidants in cardiomyocyte sarcolemmal preparations (decreased lipid peroxidation-derived carbon-centered free radical formation) exposed to an iron-catalyzed oxygen free radical system (Mak et al. 1989; Mak and Weglicki 1992). The naphthoxyl linkage of propranolol confers most of its antioxidant characteristics, and a lipophilic drug – biomembrane interaction was essential to achieve effectiveness. Beta-blockers that are more water soluble, like atenolol and sotalol, were not effective membrane chain breaking antioxidants and (or) cyto-protective agents (Mak and Weglicki 1988; Kramer et al. 1991), and also argue against β-adrenergic receptor blockade as a major contributor to the observed beneficial effects of d-Pro. In oxidatively-stressed cellular (Kramer et al. 1991; Mak et al. 2006) and perfused heart models (Kramer et al. 1994, 2006), the protective effects of d-Pro required prolonged treatment (>30 min) to allow active uptake. In addition, we (Dickens et al. 2002) and others (Cramb 1986) have shown that lysosomes are principle sites of propranolol accumulation within cells, and that propranolol can preserve the stability of lysosomes when exposed to exogenous free radicals in vitro (Kramer et al. 2006). Compounds containing basic amine groups (ethanolamine side chain) like propranolol, possess lysosomotropic properties and raise lysosomal pH (alkalinization) (Dickens et al. 2002; Mak et al. 2006). Since lysosomes are also a primary storage depot for cellular iron (Eaton and Qian 2002; Mak et al. 2006), agents causing alkalinization may afford protection by enhancing iron binding to lysosomal ferritin (major tissue storage protein) (Berenshtein et al. 2002), and diminish low molecular weight lysosomal iron (redox active) release during oxidative stress (Voogd et al. 1992; Whittaker et al. 1996). Indeed, we have shown that the protective effects of acute d-Pro against oxidative injury to iron-loaded rat peritoneal macrophages (lower release of iron and reactive oxygen species) (Komarov et al. 2006), and to postischemic hearts from iron-loaded rats (improved cardiac function, and lower release of tissue iron, lactate dehydrogenase, conjugated dienes, and lysosomal NAGA) (Kramer et al. 2006) were largely related to its membrane antioxidant and lysosomotropic properties.

This latter study (Kramer et al. 2006) provided the basis for using d-Pro as an in-vivo treatment during short-term (3 week) and prolonged (up to 5 weeks) Fe overload in rats. Chronic d-Pro treatment during 3 weeks of iron overload was substantially protective against iron-mediated oxidative stress and tissue injury in vivo, and restored normal hemodynamic/functional properties to perfused hearts. d-Pro's protective effects may be partly related to its ability to modulate endogenous Fe status. d-Pro significantly decreased ventricular tissue iron content as well as both atrial and ventricular tissue iron deposition in iron overloaded rats. Thus, d-Pro not only limited iron release from oxidatively-stressed heart and cellular models (Kramer et al. 2006; Komarov et al. 2006), but it effectively reduced cardiac tissue iron uptake (this study). During iron overload, nontransferrin bound iron in the circulation may enter the heart (in ferrous form) through L-type calcium channels (Tsushima et al. 1999; Murphy and Oudit 2010), and (or) by an endocytotic iron uptake mechanism (Gujja et al. 2010). The lowering effect of d-Pro on tissue iron uptake may relate to both its fluidizing effects on bio-membranes, and its alkalinizing impact on organellar pH (lysosomes and endosomes), which may disrupt pH-sensitive endocytotic processes (i.e., iron uptake, recycling of cell surface receptors) (Komarov et al. 2006). This concept is consistent with the findings of Mak et al. (2006) who reported that d-Pro pretreatment lowered lysosomal iron accumulation and attenuated oxidative injury to iron-loaded cultured bovine aortic endothelial cells. d-Pro's iron lowering effect in tissue was not restricted to the heart, since it also significantly attenuated iron accumulation in hepatic tissue (600 mg Fe·(g dry mass)−1 lower compared with Fe-alone; p < 0.05) of 3 week iron-overloaded rats.

Using echocardiography, the dose-dependent protective effects of chronic d-Pro treatment against iron-mediated cardiac dysfunction during prolonged iron exposure was clearly evident. In the absence of d-Pro, iron-overloaded rats exhibited significant LV systolic dysfunction by 3 weeks, which progressively worsened by 5 weeks.

Similar trends were observed for cardiac output, aortic Pmax, and dimensions of the LV posterior wall and interventricular septum in systole. The significant decline in mitral valve E/A ratio by week 5 may indicate early diastolic dysfunction. Our findings are in general agreement with those of Oudit et al. (2004) who used iron-overloaded (4–13 weeks) mice, whereas Moon et al. (2011) failed to observe significant systolic or diastolic functional changes in 6 week iron-overloaded mice. These varying observations might partly be due to basic differences in the iron-loading model, since both Oudit et al. (2004) and our study demonstrated heightened oxidative stress, but this was not described by Moon et al. (2011). Iron-overloaded rats receiving d-Pro (4 or 8 mg·kg−1·day−1) displayed dose-dependent preservation of LV systolic and diastolic function, of hemodynamic parameters, and of LVPWs and IVSs dimensions during 5 weeks of treatment. The lowest dose of d-Pro (2 mg) only provided modest protection against iron-mediated losses to some of these parameters at 5 weeks.

The continued presence of oxidative stress after 5 weeks of iron treatment was revealed by the elevated levels of plasma lipid peroxidation products (2.6-fold), and heightened basal superoxide production (3.2-fold) by circulating neutrophils (Kramer et al. 2009a). d-Pro, even at the middle dose (4 mg), diminished these indices of oxidative stress (35%–40% lower), permitting the speculation that persistent exposure to activated inflammatory cells during chronic iron treatment may contribute to the progressive development of cardiac dysfunction. Indeed, our observations of heightened atrial and ventricular tissue inflammation (CD11b[+] cell infiltrates) after 5 weeks of iron loading as well as the protection afforded by d-Pro (8 mg), supports this contention.

In conclusion, our studies demonstrated the deleterious impact of chronic iron overload on the development of oxidative stress, tissue injury and cardiac dysfunction in the rat. The dose-dependent beneficial effects of concurrent d-Pro treatment was independent of β-adrenergic receptor blockade, and relied on its membrane antioxidant (stabilizing) and lysosomotropic properties. d-Pro's ability to reduce cardiac tissue iron uptake, stabilize tissue lysosomes, lessen cardiac tissue inflammation, and attenuate the production of reactive oxygen species from inflammatory cells, may underlie its contribution to the preservation of cardiac function during iron overload. In this light, d-Pro might prove to be a useful adjunct therapy in combination with metal chelation when treating iron-mediated cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by Public Health Service grant NIH RO1-HL66226, and a grant from the Richard B. and Lynn L. Cheney Cardiovascular Institute of The George Washington University Medical Center.

References

- Bacon BR, Tavill AS, Brittenham GM, Park CH, Recknagel RO. Hepatic lipid peroxidation in vivo in rats with chronic iron overload. J. Clin. Invest. 1983;71(3):429–439. doi: 10.1172/JCI110787. doi:10.1172/JCI110787. PMID:6826715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartfay WJ, Hou D, Brittenham GM, Bartfay E, Sole MJ, Lehotay D, Liu PP. The synergistic effects of vitamin E and selenium in iron-overloaded mouse hearts. Can. J. Cardiol. 1998;14(7):937–941. PMID:9706279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berenshtein E, Vaisman B, Goldberg-Langerman C, Kitrossky N, Konijn AM, Chevion M. Roles of ferritin and iron in ischemic preconditioning of the heart. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2002;234–235(1):283–292. doi:10.1023/A:1015923202082. PMID:12162445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramb G. Selective lysosomal uptake and accumulation of the beta-adrenergic antagonist propranolol in cultured and isolated cell systems. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1986;35(8):1365–1372. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(86)90283-2. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(86)90283-2. PMID:3008762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delea TE, Edelsberg J, Sofrygin O, Thomas SK, Baladi J-F, Phatak PD, Coates TD. Consequences and costs of noncompliance with iron chelation therapy in patients with transfusion-dependent thalassemia: a literature review. Transfusion. 2007;47(10):1919–1929. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01416.x. doi:10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01416.x. PMID:17880620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickens BF, Weglicki WB, Boehme PA, Mak IT. Antioxidant and lysosomotropic properties of acridine propranolol: protection against oxidative endothelial cell injury. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2002;34(2):129–137. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1495. doi:10.1006/jmcc.2001.1495. PMID:11851353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton JW, Qian M. Molecular bases of cellular iron toxicity. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002;32(9):833–840. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00772-4. doi:10.1016/S0891-5849(02)00772-4. PMID:11978485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folden DV, Gupta A, Sharma AC, Li SY, Saari JT, Ren J. Malondialdehyde inhibits cardiac contractile function in ventricular myocytes via a p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent mechanism. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003;139(7):1310–1316. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705384. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0705384. PMID:12890710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giardina PJ, Grady RW. Chelation therapy in beta-thalassemia: the benefits and limitations of desferrioxamine. Semin. Hematol. 1995;32(4):304–312. PMID:8560288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gujja P, Rosing DR, Tripodi DJ, Shizukuda Y. Iron overload cardiomyopathy: better understanding of an increasing disorder. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010;56(13):1001–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.083. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.083. PMID:20846597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther T, Hollriegl V, Vormann J, Disch G, Classen HG. Magnesium-Bulletin. 3. Vol. 14. Haug; Heidelberg, Germany: 1992. Effects of Fe loading on vitamin E and malondialdehyde of liver, heart and kidney from rats fed diets containing various amounts of magnesium and vitamin E; pp. 88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B, Gutteridge JMC. Oxygen free radicals and iron in relation to biology and medicine: Some problems and concepts. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1986;246(2):501–514. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(86)90305-x. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(86)90305-X. PMID:3010861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershko C, Link G, Cabantchik I. Pathophysiology of iron overload. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1998;850:191–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10475.x. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10475.x. PMID:9668540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horackova M, Ponka P, Byczko Z. The antioxidant effects of a novel iron chelator salicylaldehyde isonicotinoyl hydrazone in the prevention of H(2)O(2) injury in adult cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2000;47(3):529–536. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00088-2. doi:10.1016/S0008-6363(00)00088-2. PMID:10963725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PD, Olsen N, Bagger JP, Jensen FT, Christensen T, Ellegaard J. Cardiac function during iron chelation therapy in adult non- thalassaemic patients with transfusional iron overload. Eur. J. Haematol. 1997;59(4):221–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1997.tb00981.x. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0609.1997.tb00981.x. PMID:9338620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadiiska MB, Burkitt MJ, Xiang QH, Mason RP. Iron supplementation generates hydroxyl radical in vivo. An ESR spin-trapping investigation. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;96(3):1653–1657. doi: 10.1172/JCI118205. doi:10.1172/JCI118205. PMID:7657835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarov AM, Hall JM, Chmielinska JJ, Weglicki WB. Iron uptake and release by macrophages is sensitive to propranolol. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2006;288(1–2):213–217. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9138-2. doi:10.1007/s11010-006-9138-2. PMID:16718379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontoghiorghes GJ. Comparative efficacy and toxicity of desferrioxamine, deferiprone and other Fe and aluminium chelating drugs. Toxicol. Lett. 1995;80(1–3):1–18. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(95)03415-h. doi:10.1016/0378-4274 (95)03415-H. PMID:7482575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JH, Mak IT, Freedman AM, Weglicki WB. Propranolol reduces anoxia/reoxygenation-mediated injury of adult myocytes through an anti-radical mechanism. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1991;23(11):1231–1244. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(91)90081-v. doi:10.1016/0022-2828(91)90081-V. PMID:1687065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JH, Misik V, Weglicki WB. Lipid peroxidation-derived free radical production and post-ischemic myocardial reperfusion injury. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1994;723:180–196. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb36725.x. PMID:8030864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JH, Lightfoot F, Weglicki WB. Cardiac tissue iron: effects on postischemic function and free radical production, and its possible role during preconditioning. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2000;46(8):1313–1327. PMID:11156477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JH, Murthi SB, Wise RM, Mak IT, Weglicki WB. Antioxidant and lysosomotropic properties of acute d-propranolol underlies its cardioprotection of postischemic hearts from moderate iron-overloaded rats. Exp. Biol. Med. 2006;231(4):473–484. doi: 10.1177/153537020623100413. PMID:16565443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JH, Spurney C, Iantorno M, Tziros C, Mak I-T, Tejero-Taldo MI, et al. Neurogenic inflammation and cardiac dysfunction due to hypomagnesemia. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2009;338(1):22–27. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181aaee4d. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181aaee4d. PMID: 19593099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer JH, Spurney CF, Iantorno M, Tziros C, Mak IT, Weglicki WB. D-propranolol protects against oxidative stress and progressive cardiac dysfunction in Fe-overloaded rats. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2009a;46(5 Suppl. 1):S25. doi: 10.1139/y2012-091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremastinos DT, Tiniakos G, Theodorakis GN, Katritsis DG, Toutouzas PK. Myocarditis in beta-thalassemia major. A cause of heart failure. Circulation. 1995;91(1):66–71. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.1.66. PMID:7805220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo T, Tamburino C, Bartoloni G, Morrone ML, Frontini V, Italia F, et al. Cardiac iron overload in thalassemic patients: an endomyocardial biopsy study. Ann. Hematol. 1995;71(3):135–141. doi: 10.1007/BF01702649. doi:10.1007/BF01702649. PMID: 7548332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna LG. Manual of Histologic Staining Methods of the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. 3rd ed. 1968. pp. 184–185. [Google Scholar]

- Mak IT, Weglicki WB. Protection by β-blocking agents against free radical –mediated sacrolemmal lipid peroxidation. Circ. Res. 1988;63(1):262–266. doi: 10.1161/01.res.63.1.262. PMID:2898307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak IT, Weglicki WB. Membrane antiperoxidative activities of d-propranolol, l-propranolol and dimethyl quaternary propranolol (UM-272) Pharmacol. Res. 1992;25(1):25–30. doi: 10.1016/s1043-6618(05)80061-1. doi:10.1016/S1043-6618(05)80061-1. PMID:1738755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak IT, Weglicki WB. Antioxidant activity of calcium channel blocking drugs. Methods Enzymol. 1994;234:620–630. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)34133-8. PMID: 7808338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak IT, Misra HP, Weglicki WB. Temporal relationship of free radical-induced lipid peroxidation and loss of latent enzyme activity in highly enriched hepatic lysosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258(22):13733–13737. PMID:6643449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak IT, Arroyo CM, Weglicki WB. Inhibition of sarcolemmal carbon-centered free radical formation by propranolol. Circ. Res. 1989;65(4):1151–1156. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.4.1151. PMID:2551530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak IT, Komarov AM, Wagner TL, Stafford RE, Dickens BF, Weglicki WB. Enhanced NO production during Mg deficiency and its role in mediating red blood cell glutathione loss. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 1996;271(1):C385–C390. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.1.C385. PMID: 8760069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak IT, Chmielinska JJ, Nedelec L, Torres A, Weglicki WB. D-Propranolol attenuates lysosomal iron accumulation and oxidative injury in endothelial cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006;317(2):522–528. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.097709. doi:10.1124/jpet.105.097709. PMID:16456084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak IT, Kramer JH, Chmielinska JJ, Khalid H, Landgraf K, Weglicki WB. Inhibition of neutral endopeptidase potentiates neutrophil activation during Mg-deficiency in the rat. Inflamm. Res. 2008;57(7):300–305. doi: 10.1007/s00011-007-7186-z. doi:10.1007/s00011-007-7186-z. PMID:18607539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak IT, Chmielinska JJ, Kramer JH, Weglicki WB. AZT-induced oxidative cardiovascular toxicity–attenuation by Mg-supplementation. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2009;9(2):78–85. doi: 10.1007/s12012-009-9040-8. doi:10.1007/s12012-009-9040-8. PMID:19484392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariotti E, Angelucci E, Agostini A, Baronciani D, Sgarbi E, Lucarelli G. Evaluation of cardiac status in iron-loaded thalassaemia patients following bone marrow transplantation: improvement in cardiac function during reduction in body iron burden. Br. J. Haematol. 1998;103(4):916–921. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.01099.x. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.01099.x. PMID:9886301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masini A, Trenti T, Ceccarelli D, Muscatello U. Mitochondrial involvement in causing cell injury in experimental hepatic iron overload. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1986;488:517–519. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1986.tb46587.x. [Google Scholar]

- Moon SN, Han JW, Hwang HS, Kim MJ, Lee SJ, Lee JY, et al. Establishment of secondary iron overloaded mouse model: evaluation of cardiac function and analysis according to iron concentration. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2011;32(7):947–952. doi: 10.1007/s00246-011-0019-4. doi:10.1007/s00246-011-0019-4. PMID:21656238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CJ, Oudit GY. Iron-overload cardiomyopathy: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J. Card. Fail. 2010;16(11):888–900. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2010.05.009. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2010.05.009. PMID:21055653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaya H, Tohse N, Kanno M. Electrophysiological derangements induced by lipid peroxidation in cardiac tissue. Am. J. Physiol. 1987;253(5):H1089–H1097. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.5.H1089. PMID:3688253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oudit GY, Trivieri MG, Khaper N, Husain T, Wilson GJ, Liu P, et al. Taurine supplementation reduces oxidative stress and improves cardiovascular function in an iron-overload murine model. Circulation. 2004;109(15):1877–1885. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124229.40424.80. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000124229.40424.80. PMID:15037530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepper JR, Mumby S, Gutteridge JM. Blood cardioplegia increases plasma iron overload and thiol levels during cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1995;60(6):1735–1740. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00896-9. doi:10.1016/0003-4975(95)00896-9. PMID:8787472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Politi A, Sticca M, Galli M. Reversal of haemochromatotic cardiomyopathy in beta thalassaemia by chelation therapy. Br. Heart J. 1995;73(5):486–487. doi: 10.1136/hrt.73.5.486. doi:10.1136/hrt.73.5.486. PMID: 7786668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz KA, Li Z, Schwartz DE, Cooper TG, Braselton WE. Earliest cardiac toxicity induced by iron overload selectively inhibits electrical conduction. J. Appl. Physiol. 2002;93(2):746–751. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01144.2001. PMID:12133887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taher A, Cappellini MD. Update on the use of deferosirox in the management of iron overload. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2009;5:857–868. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s5497. doi:10.2147/TCRM.S5497. PMID:19898650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsushima RG, Wickenden AD, Bouchard RA, Oudit GY, Liu PP, Backx PH. Modulation of iron uptake in heart by L-type Ca2+ channel modifiers: possible implications in iron overload. Circ. Res. 1999;84(11):1302–1309. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.11.1302. PMID:10364568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Kraaij AMM, Mostert L, van Eijk HG, Koster JF. Iron-load increases the susceptibility of rat hearts to oxygen reperfusion damage. Protection by the antioxidant (+)-cyanidanol-3 and deferoxamine. Circulation. 1988;78(2):442–449. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.78.2.442. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.78.2.442. PMID:3396180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vichinsky E. Oral iron chelators and the treatment of iron overload in pediatric patients with chronic anemia. Pediatrics. 2008;121(6):1253–1256. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1824. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-1824. PMID:18519495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voogd A, Sluiter W, van Eijk HG, Koster JF. Low molecular weight iron and the oxygen paradox in isolated rat hearts. J. Clin. Invest. 1992;90(5):2050–2055. doi: 10.1172/JCI116086. doi:10.1172/JCI116086. PMID:1430227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker P, Wamer WG, Chanderbhan RF, Dunkel VC. Effects of alpha-tocopherol and beta-carotene on hepatic lipid peroxidation and blood lipids in rats with dietary iron overload. Nutr. Cancer. 1996;25(2):119–128. doi: 10.1080/01635589609514434. doi:10.1080/01635589609514434. PMID:8710681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]