Summary

Purpose

Chemotherapy prolongs survival and improves quality of life (QOL) for good performance status (PS) patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Targeted therapies may improve chemotherapy effectiveness without worsening toxicity. SGN-15 is an antibody–drug conjugate (ADC), consisting of a chimeric murine monoclonal antibody recognizing the Lewis Y (Ley) antigen, conjugated to doxorubicin. Ley is an attractive target since it is expressed by most NSCLC. SGN-15 was active against Ley-positive tumors in early phase clinical trials and was synergistic with docetaxel in preclinical experiments. This Phase II, open-label study was conducted to confirm the activity of SGN-15 plus docetaxel in previously treated NSCLC patients.

Experimental design

Sixty-two patients with recurrent or metastatic NSCLC expressing Ley, one or two prior chemotherapy regimens, and PS ≤ 2 were randomized 2:1 to receive SGN-15 200 mg/m2/week with docetaxel 35 mg/m2/week (Arm A) or docetaxel 35 mg/m2/week alone (Arm B) for 6 of 8 weeks. Intrapatient dose-escalation of SGN-15 to 350 mg/m2 was permitted in the second half of the study. Endpoints were survival, safety, efficacy, and quality of life.

Results

Forty patients on Arm A and 19 on Arm B received at least one treatment. Patients on Arms A and B had median survivals of 31.4 and 25.3 weeks, 12-month survivals of 29% and 24%, and 18-month survivals of 18% and 8%, respectively. Toxicity was mild in both arms. QOL analyses favored Arm A.

Conclusions

SGN-15 plus docetaxel is a well-tolerated and active second and third line treatment for NSCLC patients. Ongoing studies are exploring alternate schedules to maximize synergy between these agents.

Keywords: Immunoconjugate, Targeted therapy, NSCLC, Lewis Y, SGN-15, Monoclonal antibody

1. Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related death with over one million deaths annually worldwide and over 160,000 deaths in the US in 2004 [1]. Non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) accounts for 80% of lung cancer diagnoses [2]. Most NSCLC patients are diagnosed with advanced stage disease not amenable to surgical cure [3]. Although some stage III patients can be cured with combined modality therapy, most advanced stage patients receive chemotherapy alone resulting in clinical response or disease stabilization in many cases, but with few long-term survivors [4–6]. Front line treatment with platinum doublet chemotherapy now produces median survivals of 8–11 months and provides clinically meaningful overall survival benefits, with 1 year survivals for stage IV NSCLC patients of 30–50% compared to 5–10% for patients receiving supportive care alone.

Taxanes are among the most active NSCLC chemotherapies acting on cells in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle by stabilizing microtubules, thus, disrupting normal mitosis and leading to activation of apoptotic pathways in sensitive cells. Both paclitaxel and docetaxel are approved in combination with cisplatin for first line therapy of NSCLC. Docetaxel is also approved as a single agent for patients who have failed first line chemotherapy and is associated with quality of life gains and survival benefits similar to those seen with first line therapy. Patients treated with second line docetaxel have about a 30% chance of living 1 year [7,8]. In the face of these modest gains, new approaches to systemic therapy of advanced NSCLC are needed.

Anthracyclines have low single agent activity against NSCLC, but doxorubicin was a component of CAP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin), one of the first chemotherapy regimens to show a survival benefit in this disease [9]. Anthracyclines have been largely supplanted in recent combination chemotherapy regimens in favor of newer agents. However, if effective targeting can increase the specificity of drug delivery and if rational combinations successfully exploit synergistic cell cycle dependent interactions, they may hold greater promise than previously appreciated.

SGN-15 (cBR96-doxorubicin conjugate) is a novel antibody–drug conjugate that targets doxorubicin to tissues expressing the Ley antigen. This carbohydrate antigen is abundantly expressed (>200,000 molecules/cell) by carcinoma cells [10]. Tissue binding studies show that cBR96 targets a wide variety of human carcinomas including lung, breast, colon, prostate, and ovary [10]. cBR96 also targets normal cells expressing Ley, including differentiated epithelial cells of the GI tract and acinar cells of the pancreas. SGN-15 consists of doxorubicin conjugated to cBR96 at a molar ratio of 8:1 with 6 mg doxorubicin per 200 mg SGN-15. Phase I studies of SGN-15 showed evidence of activity in patients with Ley expressing tumors [11]. Of 58 evaluable patients, 21 (36%) had stable disease after 6 weeks and there were two partial responses.

SGN-15 and docetaxel are synergistic in preclinical studies. Following exposure to doxorubicin, cells arrest in G2 [12] and are then sensitized to G2/M acting drugs such as taxanes. In vitro studies [13] and animal models [14] confirm that the combination of SGN-15 plus a taxane is more effective than either drug alone in several tumor types. Phases I and II studies in subjects with epithelial malignancies, including metastatic breast and colorectal carcinomas, confirm that the combination of SGN-15 and docetaxel is safe and clinically active [15–18] (unpublished data, Seattle Genetics, Inc.). In 29 evaluable patients with breast cancer, the disease control rate (i.e. stable disease or better) was 41% (seven stable disease [SD], two minimal response [MR], three partial response [PR]). Among 20 evaluable patients with colorectal carcinoma, the disease control rate was 20% (three SD, one MR). The toxicity profile was acceptable with gastrointestinal toxicities occurring most frequently. Other toxicities were mild and infrequent.

We now report the results of a randomized Phase II, multicenter study designed to determine the safety and efficacy of SGN-15 and docetaxel in patients with NSCLC.

2. Materials studied, methods, techniques

2.1. Patients

Patients with recurrent or progressive advanced non-small cell lung cancer not amenable to therapy with curative intent were eligible for this trial if they had failed at least one but not more than two prior chemotherapy regimens at least one of which must have contained a platinum. Patients must have been at least 4 weeks past prior treatment with recovery from significant toxicities. Measurable or evaluable disease, ECOG performance status (PS) ≤ 2, age at least 18 years, and life expectancy of at least 3 months were required. Only patients whose tumors expressed Ley by immunohistochemistry (IHC) were eligible. Patients previously treated with docetaxel for metastatic disease, with cumulative anthracycline exposure >300 mg/m2, with another active cancer, or with uncontrolled significant non-malignant disease were not eligible. The first patient was randomized 1 August 2001; the last patient was enrolled 17 April 2003.

2.2. Methods

This multicenter, randomized, Phase II trial was conducted at 11 sites in the US. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards or Ethics Committees of all participating research centers. Patients provided informed consent before undergoing any procedures that were not part of normal patient care. Tissue samples were sent to a central pathology lab (Impath, Los Angeles, CA) to be tested for Ley expression by IHC with results scored 0–3+. Any expression over background was considered eligible. After registration, patients were randomized to receive SGN-15 + docetaxel (Arm A) or docetaxel alone (Arm B). Randomization was weighted 2:1 in favor of Arm A and was stratified by gender and ECOG performance status (0–1 versus 2).

During the first half of the study (20 patients on Arm A and 12 patients on Arm B), patients in Arm A received 200 mg/m2 SGN-15 (6 mg doxorubicin) infused over 2 h followed by 35 mg/m2 docetaxel infused over 30–60 min weekly for 6 weeks, followed by 2 weeks off. The initial dose of SGN-15 was based on prior studies with consideration for the potential for pancreatitis and other gastrointestinal toxicity. However, in this study no significant GI toxicity was observed at the 200 mg/m2 dose. In order to maximize SGN-15 dose and investigate the possibility of increased efficacy at higher doses, the study was amended in June 2002, to dose-escalate SGN-15 in Arm A patients in weekly 50 mg/m2 increments up to 350 mg/m2/week in the absence of ≥Grade 2 gastrointestinal toxicity. Additionally, the dosing schedule was modified while maintaining equal dose intensity so that within the 8-week cycle, patients received two courses of 3 weeks on treatment and 1 week off, corresponding more closely with other common chemotherapy regimens. A maximum of 48 weeks of treatment was permitted.

Patients on Arm B received 35 mg/m2 docetaxel weekly on the same schedule as Arm A. Doses of SGN-15 and docetaxel were reduced as needed according to standard dose reduction criteria as specified in the protocol. Routine pre-medications included H2 receptor antagonist, 5HT3 receptor antagonist, diphenhydramine prior to SGN-15, and dexamethasone 8 mg IV 1 h prior to and orally 12 h after docetaxel.

Serum was collected for pharmacokinetic analyses pre-treatment, 1 h post-infusion of docetaxel, and 24 h post-infusion of docetaxel for each of the six doses in the first 8 weeks of therapy. Serum samples were stored at ≤−20 °C until analysis (PPD). Quantitative methods to measure intact SGN-15 are not currently available, thus both the antibody portion and doxorubicin component of SGN-15 were measured. Clearance of the antibody component of SGN-15 (cBR96) was measured by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with a lower limit of detection of 1.00 μg/mL. The total concentration of doxorubicin was measured by HPLC-MS after releasing doxorubicin bound to cBR96 by incubating serum at pH 2 for 1 h at room temperature. The lower limit of detection for the doxorubicin LC/MS assay was 10 μ/mL. Actual cBR96 and total doxorubicin values were compared to predicted serum concentrations generated by compartmental modeling, based on previously reported SGN-15 PK values [11] using WinNonlin version 4.0.

Adverse events were graded using the NCI Common Terminology Criteria version 2.0 and coded by the MedDRA system. Response was measured every 8 weeks using the RECIST criteria for patients with measurable disease [19]. Quality of life was monitored using the self-administered FACT-L [20] and FACT-taxane [21] instruments, scored according to the Center on Outcomes, Research, and Education (CORE) method. Survival was recorded from the date of first study treatment to date of death or last contact.

The primary endpoint was the disease control rate as defined by CR + PR + SD based on RECIST criteria. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals were constructed for the response rate for each treatment group. Survival and progression-free survival were measured and compared using the log-rank test. The incidences of AEs occurring in each arm were compared using Fisher’s exact test.

2.3. Sample size justification

Forty evaluable patients were to be enrolled in the SGN-15/docetaxel treatment arm and 20 patients in the docetaxel arm using a 2:1 weighted randomized scheme. This sample size provided a standard deviation of 8% or less for the projected response rate in the SGN-15/docetaxel treatment arm and a standard deviation of 11% or less for the projected response rate in the docetaxel arm.

3. Results

Sixty-two subjects were enrolled at 11 sites between August 2001 and April 2003. Three patients did not receive study treatment: one patient in Arm A had a decline in PS prior to treatment and was removed from the study and two patients in Arm B withdrew consent prior to treatment. Fifty-nine patients, 40 in Arm A and 19 in Arm B, received at least one dose of study medication and were evaluated for survival and toxicity. The median number of weeks on study treatment was 8.2 in Arm A and 8.1 in Arm B. Patient characteristics for the 59 patients receiving at least one dose of study treatment are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline disease characteristics

| Variable | SGN-15 + docetaxel (Arm A; N = 40) | Docetaxel (Arm B; N = 19) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years (median, range) | 62 (40–78) | 56 (39–75) |

| Gender: male/female | 20/20 | 9/10 |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 31 (78%) | 19 (100%) |

| Other | 9 (23%) | 0 |

| ECOG performance status | ||

| 0 | 12 (30%) | 7 (37%) |

| 1 | 24 (60%) | 10 (53%) |

| 2 | 4 (10%) | 2 (10%) |

| Number of prior chemotherapy regimens | ||

| 1 | 24 (60%) | 14 (74%) |

| >1 | 16 (40%) | 5 (26%) |

| Months since most recent therapy (median, range) | 2 (1–34) | 2 (0–28) |

| Histologya | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 28 (70%) | 14 (74%) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 10 (25%) | 4 (21%) |

| Other | 2 (5%) | 1 (5%) |

| Measurable disease | 37 (93%) | 19 (100%) |

| Number of sites of measurable diseaseb | ||

| 1 | 18 (45%) | 4 (21%) |

| 2 | 4 (10%) | 7 (37%) |

| >2 | 15 (38%) | 8 (42%) |

Histology data collected directly from sites, not recorded on CRF.

Three patients were enrolled on Arm A who did not have measurable disease.

3.1. Toxicity of study treatment–adverse events

Incidence of most adverse events appeared similar in the two treatment arms, and most were attributable to either docetaxel or the underlying disease. Gastrointestinal events appeared more common in Arm A, consistent with the known GI toxicity of cBR96. GI events were generally mild to moderate, transient, and were not responsible for study discontinuation except for four patients receiving SGN-15. Vomiting in patients on Arm A was generally confined to a brief episode precipitated by coughing during the SGN-15 infusion; delayed vomiting was not seen. Grades 3–5 adverse events are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Grades 3–5 adverse events, in order of overall occurrence, irrespective of relationship to therapy

| MedDRA preferred term | SGN-15 + docetaxel (Arm A; N = 40) | Docetaxel (Arm B; N = 19) |

|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal | ||

| Increased lipase/increased amylasea/pancreatitis NOSb | 10 (25%) | 1 (5%) |

| Nausea/vomiting NOS | 7 (18%) | 1 (5%) |

| Stomatitis/glossodynia/mucosal inflammation NOS | 4 (10%) | |

| Dehydration | 2 (5%) | 1 (5%) |

| Abdominal pain NOS | 1 (3%) | |

| Dysphagia | 1 (3%) | |

| Gastrointestinal haemorrhage NOS | 1 (3%) | |

| Hiccups | 1 (3%) | |

| Small intestinal obstruction NOS | 1 (3%) | |

| Respiratory and thoracic | ||

| Pneumonia/lung infiltrates NOS | 5 (13%) | 2 (11%) |

| Respiratory distress/dyspnoea NOS | 4 (10%) | 3 (16%) |

| Pleural effusion | 2 (5%) | |

| Pulmonary embolism | 2 (5%) | |

| Bronchitis NOS | 1 (3%) | |

| Chest pain | 1 (3%) | 1 (5%) |

| Hypoxia | 1 (5%) | |

| Respiratory failure | 1 (5%) | |

| Musculoskeletal | ||

| Arthralgia | 2 (5%) | 2 (11%) |

| Back pain | 1 (3%) | 1 (5%) |

| Bone pain | 1 (3%) | |

| General disorders | ||

| Asthenia/fatigue/malaise | 5 (13%) | 2 (11%) |

| Intractable pain | 2 (5%) | 1 (5%) |

| Oedema peripheral | 1 (3%) | 1 (5%) |

| Performance status decreased | 1 (5%) | |

| Metabolism and nutritional | ||

| Diarrhoea NOS | 2 (5%) | 1 (5%) |

| Anorexia | 1 (3%) | |

| Vascular disorders | ||

| Deep vein thrombosis | 2 (5%) | |

| Hypotension NOS | 1 (3%) | |

| Hematologic | ||

| Neutropenia NOS | 2 (5%) | 1 (5%) |

| Anemia NOS | 1 (3%) | |

| Nervous system disorders | ||

| Neuropathy NOS | 1 (3%) | 1 (5%) |

| Cardiac | ||

| Pericardial effusion/pericarditis | 1 (3%) | 1 (5%) |

| Cardio-respiratory arrest | 1 (3%) | |

| Hypertension NOS | 1 (3%) | |

| Psychiatric disorders | ||

| Anxiety | 1 (5%) | |

| Insomnia | 1 (3%) | |

| Infections | ||

| Bacteremia | 1 (3%) | |

| Cellulitis | 1 (3%) | |

| Herpes zoster | 1 (3%) | |

| Sepsis NOS | 1 (3%) | |

| Injury | ||

| Femur fracture | 1 (5%) | |

| Surgical and medical procedures | ||

| Pleurodesis | 1 (3%) | |

| Skin and subcutaneous disorders | ||

| Skin reaction | 1 (3%) | |

NOS: not otherwise specified.

One patient had abnormal amylase at baseline.

One patient had pancreatitis (chemical only).

3.2. Dose escalation of SGN-15

Twenty patients on Arm A enrolled under the amended schedule and dosing regimen. Forty-five percent of eligible patients reached the maximum allowed dose of 350 mg/m2 SGN-15. Reasons for not reaching the maximum SGN-15 dose included Grade 2 nausea, vomiting, anorexia, heartburn, GI bleed, and mucositis (five patients at a dose of 250 mg/m2 and one patient at 200 mg/m2), asymptomatic elevation of lipase (one patient at 300 mg/m2), progression of disease or decreased PS (one patient each at 200 and 300 mg/m2), central line infection (one patient at 250 mg/m2), and Grade 3 nausea and vomiting (one patient at 300 mg/m2).

3.3. Efficacy of study treatment–tumor response and survival

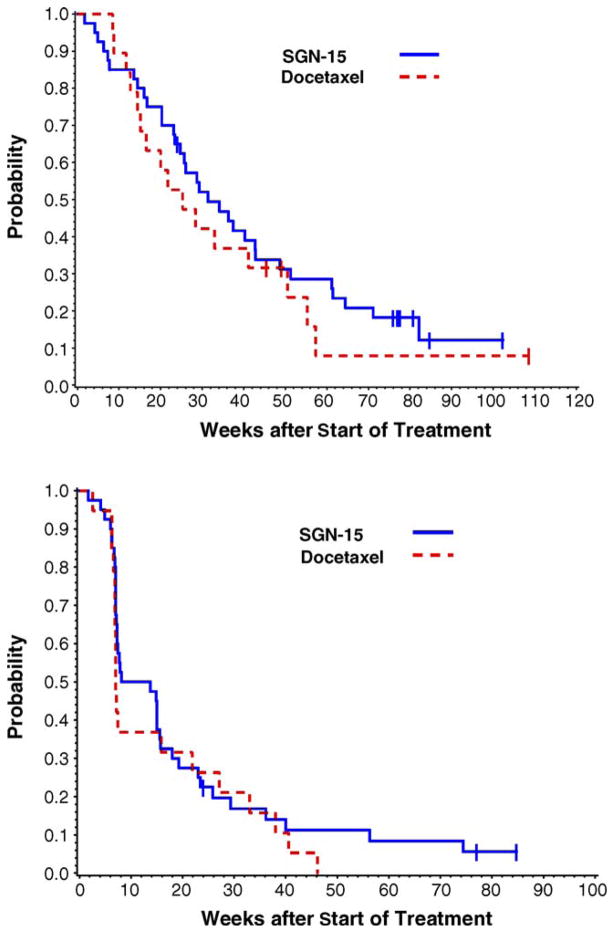

Objective tumor responses (complete or partial response) by RECIST criteria, were observed in two patients in Arm A (6%) and four patients in Arm B (21%). Fourteen patients (40%) in Arm A and three (16%) in Arm B had stable disease (Table 3). Median survival and estimated probability of surviving more than 1 year were higher in Arm A; median survival was 31.4 weeks (range 1.7–102.3+ weeks) in Arm A and 25.3 weeks (range 8.4–108.6+ weeks) in Arm B (see Fig. 1). One-year survival was 29% in Arm A and 24% in Arm B. Eighteen-month survival was 18% in Arm A and 8% in Arm B. The median progression-free survival was 10.9 weeks in Arm A and 7.0 weeks in Arm B. The 1-year PFS survival probability was 11% in Arm A and 0% in Arm B.

Table 3.

Response in patients with measurable diseasea

| SGN-15 + docetaxel (Arm A; N = 35)a | Docetaxel (Arm B; N = 19)a | |

|---|---|---|

| CR | 1 (3%) | 0 |

| PR | 1 (3%) | 4 (21%) |

| SD | 14 (40%) | 3 (16%) |

| CR + PR + SD | 16 (46%) | 7 (37%) |

| PD | 19 (54%) | 12 (63%) |

Modified intent to treat population: all patients who were randomized, received at least one dose of therapy, and were evaluable per RECIST criteria.

Fig. 1.

Survival (top) and progression-free survival (bottom) were followed for the 40 subjects on Arm A and the 19 subjects on Arm B who received at least one dose of study drug. Seven patients (18%) in Arm A and three patients (16%) in Arm B were censored for survival. Median survival was 31.4 weeks (range 1.7–102.3+ weeks) in Arm A and 25.3 weeks (8.4–108.6+ weeks) in Arm B. Three subjects in Arm A (8%) and no subjects in Arm B were censored for PFS. The median PFS was 10.9 weeks in Arm A and 7.0 weeks in Arm B. The 1-year progression-free survival probability was 11% in Arm A and 0% in Arm B.

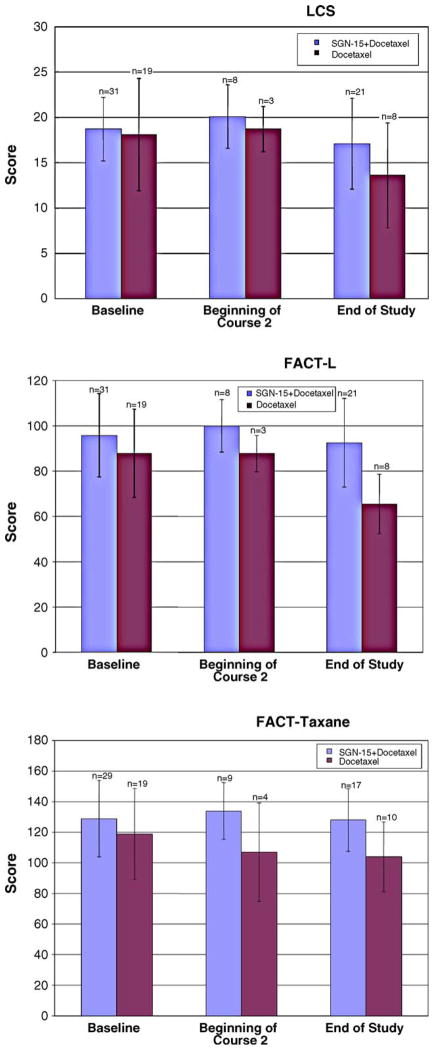

3.4. Effect of study treatment on quality of life measures

Quality of life was assessed using the self-administered FACT-L and FACT-taxane (Fig. 2). Overall, quality of life declined for all patients in the study from baseline to end of treatment. The decline from baseline to end of study was less pronounced in nearly every category for patients treated with SGN-15 plus docetaxel, compared with docetaxel alone (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Mean quality of life scores at baseline, beginning of Course 2, and at end of study, as assessed using the FACT-L lung cancer subscale (top), FACT-L total score (middle), and FACT-taxane total score (bottom). Bars show standard deviations.

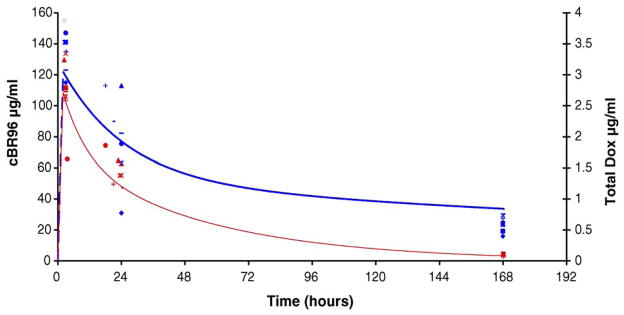

3.5. Pharmacokinetics

Prior to this study, there was no information about the effect of docetaxel on clearance of SGN-15 in humans. Serum from the first cycle of treatment was subjected to pharmacokinetic analysis as measured by cBR96 and doxorubicin serum levels. A comparison of predicted PK data for cBR96 and doxorubicin relative to actual values is shown in Fig. 3. The actual values for cBR96 and doxorubicin are in good agreement with predicted values from single agent modeling (i.e. without co-administration of docetaxel). These data suggest that docetaxel at this dose and schedule had little effect on clearance of SGN-15 or its components.

Fig. 3.

Symbols represent actual serum levels of cBR96 (blue) and doxorubicin (red) from patients treated with 200 mg/m2 of SGN-15. The lines represent model predicted serum levels of cBR96 (blue) and doxorubicin (red) generated using WinNonlin. The model predicted clearance values were 9 mL/h/m2 for cBR96 and 1900 mL/h/m2 for doxorubicin. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of the article.)

4. Discussion and conclusion

This randomized Phase II study shows that the combination of SGN-15 and docetaxel is active in NSCLC patients who have failed up to two chemotherapy regimens including at least one platinum-containing regimen. The study treatment was well tolerated without a clinically meaningful difference in toxicity of the combination arm compared to weekly docetaxel alone. Patients on the combination arm had a longer median survival (31.4 weeks versus 25.3 weeks) and a better chance of living 18 months (18% versus 8%) than patients treated with docetaxel alone. The survival curves for this group of patients, 40% of whom had failed two prior chemotherapy regimens, are encouraging and justify further study of this regimen.

Unplanned, retrospective analysis of the two SGN-15 dose schedules led to some hypothesis-generating findings. The first 20 patients treated on Arm A (SGN-15, 200 mg/m2, plus docetaxel) had a longer median survival (61.4 weeks) and progression-free survival (15 weeks) than that of the overall study population. This correlates with a longer duration on study for patients treated at the original SGN-15 dose of 200 mg/m2. Longer time on treatment may simply be a surrogate for longer survival, but the optimal dosing strategy for SGN-15 is not well defined. For the patients treated at 200 mg/m2 of SGN-15, 13 of 20 had no dose reductions or skipped doses during cycle 1. In contrast, only 5 of 20 patients on the dose-escalation schedule received the planned infusion dose and number of infusions (six had at least one dose skipped and nine had a dose reduction or did not escalate their dose), suggesting considerable toxicity related to the dose escalation. Furthermore, we can speculate that a lower dose of antibody–drug conjugate or a longer time between cycles may optimize the synergistic interaction with docetaxel because of the relatively rapid kinetics of dissociation of doxorubicin from cBR96 and comparatively long time that receptor sites are occupied by unconjugated antibody [11]. This provocative analysis is speculative and serves to define hypotheses that could be tested in future trials.

PK data from this study do not suggest perturbation of SGN-15 clearance, measured as either the cBR96 antibody or total doxorubicin, by docetaxel. Plasma PK of docetaxel was not assessed in this study; however, based on available drug–drug interaction data, it is more likely that docetaxel would have altered, albeit modestly, the kinetics of doxorubicin clearance once released from SGN-15. Nonetheless, confirmation that SGN-15 does not alter the PK of docetaxel is an important point to be addressed, and is currently under investigation.

Since previous data suggest a pharmacologic interaction between SGN-15 and docetaxel, consideration of how to maximize this effect is needed. In vitro data from Wahl et al. suggest that the maximum effect in terms of tumor cell killing is achieved if SGN-15 precedes docetaxel application by 24 h [13]. Additional preclinical work using a nude mouse xenograft model (unpublished data, Seattle Genetics, Inc.) showed that administration of SGN-15 48 h before docetaxel administration led to increased clinical response compared to either concomitant administration of the drugs or administration of docetaxel prior to SGN-15. The current study evaluated SGN-15 administered immediately before docetaxel, which, given the differences in pharmacokinetic properties of the two drugs, likely resulted in the concentration of docetaxel reaching peak levels at or before SGN-15 [22] (unpublished data, Seattle Genetics, Inc.). In order to more closely mimic the conditions studied in vitro, dosing schedules in vivo that separate the administration of SGN-15 from docetaxel by longer time intervals (i.e. more than 24 h) or alternate administration schedules of SGN-15, such as continuous infusion, could be explored.

Objective response rates to second-line docetaxel given once every 3 weeks at 75 mg/m2 have been reported as 5–20% in Phase II studies and 5–10% in Phase III studies [7,8]. The overall response rate of approximately 10% to weekly docetaxel for our entire study population is comparable to that reported in the literature for the more traditional regimen, and in conjunction with other studies [23] confirms that a weekly docetaxel regimen may be equivalent to the more toxic every 3-week schedule. The addition of SGN-15 to docetaxel did not add appreciably to adverse events. The low incidence of adverse events in this study compares favorably with the toxicity of pemetrexed or of docetaxel given on a once every 21-day schedule. Quality of life analysis demonstrates a similar or better outcome for patients treated with SGN-15 plus docetaxel compared with patients treated with docetaxel alone.

The use of second- and third-line therapies for patients with NSCLC is associated with benefits in both overall survival and slowed rate of decline in quality of life. Fosella and Shepherd each demonstrated in Phase III trials longer survival with better quality of life with docetaxel compared to vinorelbine or ifosfamide [7] or best supportive care (BSC) [8]. Hanna et al. demonstrated equivalent survival with less toxicity for pemetrexed versus docetaxel (every 21 days schedule) in the same setting [24]. Shepherd has confirmed survival and quality of life benefits for erlotinib versus BSC in the second- and third-line settings [25]. We show here that docetaxel has similar efficacy when given on a weekly schedule to that shown in earlier trials of the more toxic every 21-day regimen, and that docetaxel plus SGN-15 on a weekly schedule is well tolerated with suggested benefits in both survival and quality of life. Further study of this combination appears to be warranted in NSCLC.

Acknowledgments

Sincere thanks are extended to Michael MacDonald, MD, Amy Sing, MD, Andrew Sandier, MD, J. Michael White, PhD, Jennie Lorenz, CCRA, Katie Herz, CRA, Brenda Fisher, RN, Esther Bit-Ivan, Livia Szeto, RN, Cara O’Keefe, Joanne Jelliffe, Christine Baker, RN, Heather Houston, RN, Cheryl Elzinga, Inger Thompson, Carol Ford, RN, Diane Perry, RN, and all of the clinical trial site personnel for their assistance in conducting this trial. We are grateful to Stephanie Boyer for her invaluable assistance in preparing this manuscript. This study was sponsored by Seattle Genetics, Inc.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

All authors, with the exception of those employed by Seattle Genetics, have indicated no potential conflicts of interest. The employees of or contractors to Seattle Genetics include Laurie Grove, Michael Thorn, Dennis Miller, and Jonathan Drachman.

References

- 1.Cancer facts and figures. American Cancer Society; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landis SH, Murray T, Bolden S, Wingo PA. Cancer statistics 1999. CA Cancer J Clin. 1999;49:8–31. 1. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.49.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ginsberg RJ. Continuing controversies in staging NSCLC: an analysis of the revised 1997 staging system. Oncology (Williston Park) 1998;12:51–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gandara DR, Chansky K, Albain KS, et al. Consolidation docetaxel after concurrent chemoradiotherapy in stage IIIB non-small-cell lung cancer: phase II Southwest Oncology Group Study S9504. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2004–10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, et al. Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:92–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milton DT, Miller VA. Advances in cytotoxic chemotherapy for the treatment of metastatic or recurrent non-small cell lung cancer. Semin Oncol. 2005;32:299–314. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fossella FV, DeVore R, Kerr RN, et al. Randomized phase III trial of docetaxel versus vinorelbine or ifosfamide in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-containing chemotherapy regimens. The TAX 320 Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2354–62. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.12.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shepherd FA, Dancey J, Ramlau R, et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2095–103. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.10.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knost JA, Greco FA, Hande KR, Richardson RL, Fer MF, Oldham RK. Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Treat Rep. 1981;65:941–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hellstrom I, Garrigues HJ, Garrigues U, Hellstrom KE. Highly tumor-reactive, internalizing, mouse monoclonal antibodies to Le(y)-related cell surface antigens. Cancer Res. 1990;50:2183–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saleh MN, Sugarman S, Murray J, et al. Phase I trial of the anti-Lewis Y drug immunoconjugate BR96-doxorubicin in patients with Lewis Y-expressing epithelial tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2282–92. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.11.2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ling YH, el-Naggar AK, Priebe W, Perez-Soler R. Cell cycle-dependent cytotoxicity, G2/M phase arrest, and disruption of p34cdc2/cyclin B1 activity induced by doxorubicin in synchronized P388 cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1996;49:832–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wahl AF, Donaldson KL, Mixan BJ, Trail PA, Siegall CB. Selective tumor sensitization to taxanes with the mAb-drug conjugate cBR96-doxorubicin. Int J Cancer. 2001;93:590–600. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trail PA, Willner D, Bianchi AB, et al. Enhanced antitumor activity of paclitaxel in combination with the anticarcinoma immunoconjugate BR96-doxorubicin. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:3632–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hart L, Redfern C, Srinivas S, et al. A phase II study of SGN-15 (cBR96-doxorubicin immunoconjugate) combined with docetaxel in patients with hormone refractory prostate carcinoma. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2002 [Abstr 2433] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hart LL, Nabell L, Saleh M, et al. A phase II study of SGN-15 (cBR96-doxorubicin immunoconjugate) combined with docetaxel for the treatment of metastatic breast carcinoma. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2003;22:174. [Abstr 696] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nabell L, Sing A, Siegall C, Lobuglio A, Saleh M. A phase I study of combined modality therapy using SGN-15 with docetaxel (Taxotere®) for the treatment of metastatic breast and colorectal carcinoma. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2001 [Abstr 2251] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nabell L, Saleh M, Marshall J, et al. Phase II study of SGN-15 (cBR96-doxorubicin immunoconjugate) combined with docetaxel for the treatment of metastatic breast and colorectal carcinoma. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2002 [Abstr 55] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–16. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cella DF, Bonomi AE, Lloyd SR, Tulsky DS, Kaplan E, Bonomi P. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung (FACT-L) quality of life instrument. Lung Cancer. 1995;12:199–220. doi: 10.1016/0169-5002(95)00450-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cella D, Peterman A, Hudgens S, Webster K, Socinski MA. Measuring the side effects of taxane therapy in oncology: the functional assessment of cancer therapy-taxane (FACT-taxane) Cancer. 2003;98:822–31. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bissery MC. Preclinical pharmacology of docetaxel. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A(Suppl 4):S1–6. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00357-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gridelli C, Gallo C, Di Maio M, et al. A randomised clinical trial of two docetaxel regimens (weekly vs 3 week) in the second-line treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. The DISTAL 01 study. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:1996–2004. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hanna N, Shepherd FA, Fossella FV, et al. Randomized phase III trial of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1589–97. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]