Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To study differences in baseline characteristics and outcomes of patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) receiving first-line docetaxel-containing chemotherapy on prospective clinical studies (trial participants) versus those receiving this therapy outside of a clinical study (non-participants).

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Records from 247 consecutive chemotherapy-naive patients who were treated with docetaxel-containing chemotherapy for mCRPC at a single high-volume centre from 1998 to 2010 were reviewed.

All patients received docetaxel either as clinical trial participants (n = 142; 11 separate studies) or as non-participants (n = 105).

Univariable and multivariable Cox regression models predicted overall survival after chemotherapy initiation.

RESULTS

There was no significant difference between trial participation and non-participation with respect to patient age, type of primary treatment, tumour grade or clinical stage.

Multivariable analyses showed a significantly lower risk of all-cause mortality (hazard ratio 0.567; P = 0.027) among trial participants vs non-participants.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients that were treated with docetaxel for mCRPC showed a significantly longer overall survival when enrolled in a clinical trial.

Improved survival in trial participants may reflect the better medical oversight typically seen in patients enrolled in trials, more regimented follow-up schedules, or a positive effect on caregivers’ attitudes because of greater contact with medical services.

With the retrospective nature of this analysis and the small study population, prospective studies are needed to validate the present findings and to further investigate the relationship between clinical trial participation and outcomes.

Keywords: prostate cancer, chemotherapy, clinical trial, metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, docetaxel, overall survival

INTRODUCTION

Several proven chemotherapeutic options are available for men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). In addition to docetaxel, which remains the standard initial systemic therapy for mCRPC [1,2], three novel therapies (cabazitaxel, abiraterone and sipuleucel-T) have been shown to improve overall survival [3-10], even though a curative treatment option is still needed.

Several alternative therapeutic targets and approaches such as additional androgen-modulating approaches, cancer vaccines, angiogenesis inhibitors, epigenetic therapies and poly-ADP ribose polymerase inhibitors are being developed for the treatment of advanced prostate cancer [9,11,12].

Clinical trials are widely recognized as the optimal way to evaluate the efficacy of new investigational treatment options or for comparing different established therapies [13]. However, the progress of clinical trials is limited by the accrual rates of patients that are willing to participate [14-16]. Several factors can affect patient motivation for trial enrolment [13,17-20]. Even if participation is not hindered by the limited availability of appropriate trials or socioeconomic and geographical factors restricting access to trials, concerns about the uncertainty associated with the experimental nature of trials and the process of randomization (in the case of randomized trials) have been documented to act as barriers for enrolment [13,18]. On the other hand, hope for personal benefit by accessing a potentially more effective therapy or for active contribution to research through altruistic motives (generating benefit for others who may have the same disease in the future) may lead to trial enrolment [13,17-19].

Several reports have suggested the existence of a ‘trial effect’, whereby participants may experience improved clinical outcomes simply by participation in a clinical trial itself [13,21]. However, in the case of advanced prostate cancer, there are insufficient data to show whether outcomes of patients with mCRPC receiving first-line docetaxel-containing chemotherapy on clinical trials are better than those of patients receiving docetaxel off-study. The demonstration of improved survival among clinical trial participants would constitute an important piece of evidence in support of enrolment in clinical trials on the basis of a potential direct benefit of trial participation in itself. In the present study, we retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients with mCRPC who received docetaxel-containing chemotherapy as trial participants or non-participants at a single high-volume academic medical centre.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

In this institutional review board-approved study, records from 247 consecutive patients treated with first-line docetaxel-containing chemotherapy for mCRPC at a single institution between 1 January 1998 and 31 December 2010 were reviewed. Of the 247 docetaxel-treated patients, 105 (42.5%) received docetaxel according to standard protocols at the US Food and Drug Administration-approved dose and schedule. These included patients who were not offered clinical trials, those who declined to participate, and those who were found to be ineligible for trial participation. The other 142 (57.5%) patients received docetaxel-containing chemotherapy within clinical trials. These trials included 11 separate study protocols (see Table 1). All trial participants received docetaxel or a combination of docetaxel plus an additional experimental agent that had shown beneficial effects in previous studies. The general eligibility criteria for all clinical trials included patients with adenocarcinoma of the prostate with evidence of metastases that were castration-resistant and chemotherapy-naive. Specific eligibility criteria can be found in the references for each trial [22-29] and listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Study protocols included in this analysis

| Study | NCT identifier | Title | Phase | Patients enrolled at JHU (and total) | Date | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CALGB-90401 | NCT00110214 | A Randomized Double-Blinded Placebo Controlled Phase III Trial Comparing Docetaxel and Prednisone With and Without Bevacizumab In Men With Hormone Refratory Prostate Cancer | Phase III | 12 (1050) | April 2005 to March 2010 | [22] |

| SWOG-S0421 | NCT00134056 | Phase III Study of Docetaxel and Atrasentan Versus Docetaxel and Placebo for Patients With Advanced Hormone Refractory Prostate Cancer | Phase III | 20 (1038) | August 2006 to April 2010 | * |

| J0091 | – | A Multi-Center, Non-Randomized, Open Label Phase II Study Evaluating Docetaxel Plus Exisulind in Patients with Hormone Refractory Prostate Cancer | Phase II | 11 (14) | March 2002 to November 2003 | [23] |

| ASCENT Trial | NCT00043576 | Phase II/III, Multicenter, Randomized, Double Blind Study of Docetaxel Plus Calcitriol (DN-101) or Placebo in Androgen Independent Prostate Cancer | Phase II/III | 8 (250) | August 2002 to December 2005 | [24] |

| CALGB 9780 | – | A Phase II Study Evaluating Estramustine Phosphate and Docetaxel in Patients with Hormone Refractory Prostate Cancer | Phase II | 38 (47) | March 1998 to December 1998 | [25] |

| AS1404-203 | NCT00111618 | An Open Label Randomized, Phase II Study of Vadimezan (AS1404) in Combination with Docetaxel in Patients with Hormone Refractory Metastatic Prostate Cancer | Phase II | 6 (70) | May 2005 to August 2008 | [26] |

| TAX 327 | – | Multi-Center Phase III Randomized Trial Comparing Docetaxel Administration Either Weekly or Every Three Weeks in Combination with Prednisone Vs. Mitoxantrone in Combination with Prednisone for Metastatic Hormone Refractory Prostate Cancer | Phase III | 16 (1006) | March 2000 to June 2002 | [1] |

| J0467 | NCT00559429 | Phase I Trial with a Combination of Docetaxel + 153 Sm-EDTMP (Samarium 153) in Patients with Hormone-Refractory Prostate Cancer | Phase I | 14 (14) | December 2004 to October 2008 | [27] |

| VITAL-1 | NCT00089856 | A Phase III Randomized, Open-Label Study of GVAX® Vaccine Versus Docetaxel and Predinisone in Patients with Metastatic Hormone-Refractory Prostate Cancer who are Chemotherapy-Naive | Phase III | 5 (626) | July 2004 to October 2008 | [28] |

| CR005275 | NCT00401765 | A Phase I Study of a Chimeric Antibody Against Interleukin-6 (CNTO 328) Combined with Docetaxel in Subjects with Metastatic Hormone-Refractory Prostate Cancer | Phase I | 10 (40) | October 2005 to November 2009 | [29] |

| J0722 | NCT00511576 | A Phase I, Open-Label, Dose-Escalation Trial to Evaluate the Safety, Pharmacokinetics, and Pharmacodynamics of Mocetinostat (MG-0103) in Combination With Docetaxel in Subjects With Advanced Solid Malignancies | Phase I | 2 (54) | August 2007 to March 2009 | * |

Not yet published. JHU, Johns Hopkins University.

The primary objective of the current study was to determine the independent contribution of clinical trial participation on overall survival. Demographic data, pertinent laboratory values, clinical characteristics, details of previous treatment and follow-up data were recorded. In determining the number of chemotherapy cycles received, one cycle of docetaxel was defined as a single 21-day treatment period with docetaxel administered on day 1 of each treatment cycle. Measurement of disease burden and response to chemotherapy was evaluated according to the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group 2 criteria [30]. Overall survival was calculated from the date of first chemotherapy treatment with docetaxel to the date of death from any cause (or patients were censused at the date of last follow-up).

Fisher’s exact test and the chi-squared test were used to evaluate the association between categorical variables. Differences in variables with a continuous distribution across dichotomous categories were assessed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Event-time distributions for overall survival were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method [31], P-values were computed using the log-rank test, and 95% CIs were calculated by the method of Brookmeyer and Crowley described in ref [32]. Univariable and multivariable Cox regression models were used to adjust for potential confounders in predicting overall survival. All covariates with significant P values in univariable analysis were included in the multivariable model; however, only those covariates with significant P values in multivariable analysis are reported.

For all statistical analyses, P values were two-sided and P < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Splus 8.0 for Windows Enterprise Developer (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA, USA). A regression tree approach was used to find the best threshold values of confounding risk factors.

RESULTS

Baseline clinical and pathological characteristics of the entire study population are shown in Table 2. Of all 247 patients, 142 men (57.5%) constituted the trial participants and 105 (42.5%) formed the non-participants. In both groups, patients were mostly Caucasian: 118 (83%) of participants and 69 (67%) of non-participants; P = 0.005. Median age was 67.0 (±0.80) years for participants and 68 (±0.88) years for non-participants. Average Gleason score was 8.03 (±0.10) and 7.75 (±0.12) for participants and non-participants, respectively (P = 0.076). Median baseline PSA level was 61.45 ng/mL (range 0.2–5326) in the participant group and 139.1 ng/mL (range 0.1–4861) in the non-participant group (P = 0.076). Trial participants had better baseline Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status than non-participants (ECOG ≤ 1 was 92% vs 79%; P = 0.015). As primary treatment for prostate cancer, patients received radical prostatectomy, external beam radiotherapy, a combination of both, or no local treatment (see Table 2). The average number of hormonal therapies (including LHRH agonists/antagonists, antiandrogens, ketoconazole, oestrogens and others) received before chemotherapy was two in both groups. At the time of docetaxel initiation, 31% of participants and 36% of non-participants had been started on bisphosphonate therapy.

TABLE 2.

Baseline characteristics

| (N = 142) Trial participants | (N = 105) Trial non-participants | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race (white) | 118 (83) | 69 (67) | 0.005 |

| Age (years) | 67.0 ± 0.80 | 68.0 ± 0.88 | 0.381 |

| Primary treatment | |||

| Surgery | 30 (23) | 20 (20) | 0.264 |

| Radiation | 42 (33) | 43 (42) | |

| Both | 23 (18) | 23 (23) | |

| None | 33 (26) | 16 (16) | |

| Number of chemotherapy cycles | 6 (1–19) | 5 (1–18) | 0.005 |

| Gleason score | 8.03 (±0.10) | 7.75 (±0.12) | 0.076 |

| No. of previous hormonal therapies | 2 (1–5) | 2 (1–4) | 0.018 |

| Bisphosphonate use | 38 (31) | 37 (36) | 0.451 |

| Eastern cooperative oncology group score | |||

| 0 | 45 (44) | 13 (23) | 0.015 |

| 1 | 49 (48) | 32 (56) | |

| 2 | 8 (8) | 12 (21) | |

| Pain score (0–10) | 0 (0–9) | 0 (0–9) | 0.681 |

| Haemoglobin <12 g/dL | 49 (36) | 54 (52) | 0.008 |

| Albumin (U/L) | 4.25 ± 0.06 | 3.97 ± 0.08 | 0.01 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 121 (12–2970) | 152 (43–2986) | <0.001 |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | 256.2 ± 8.0 | 271.8 ± 11.1 | 0.258 |

| White blood cell count (×109/L) | 7.06 ± 2.52 | 7.81 ± 3.62 | 0.088 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.906 ± 0.022 | 1.041 ± 0.051 | 0.016 |

| AST (U/L) | 25 (12–115) | 25 (10–207) | 0.995 |

| ALT(U/L) | 21 (7–96) | 19.5 (8–125) | 0.322 |

| Presence of bone metastases | 130 (94) | 89 (86) | 0.066 |

| No. of metastases (n) | |||

| 1–3 | 18 (14) | 4 (4.5) | 0.072 |

| 4–10 | 9 (7) | 3 (3.4) | |

| >10 | 103 (79) | 82 (92) | |

| Presence of lymph node metastases | 73 (53) | 51 (49) | 0.683 |

| No. of metastases (n) >5 | 58 (79) | 39 (76) | 0.861 |

| Presence of lung metastases | 7 (5) | 10 (9.6) | 0.258 |

| No. of metastases (n) >5 | 5 (71) | 8 (80) | 0.864 |

| Presence of liver metastases | 9 (6.5) | 15 (14) | 0.066 |

| No. of metastases (n) >5 | 5 (56) | 11 (73) | 0.654 |

| Presence of measurable disease | 52 (37) | 45 (45) | 0.466 |

| Presence of objective tumour response | 26 (52) | 13 (31) | 0.068 |

| Baseline PSA at trial entry (ng/mL) | 61.45 (0.2–5326) | 139.1 (0.1– 4861) | 0.076 |

Data are presented as n (%), or mean (±SD), or median (range). AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

Positive lymph nodes were found in 73 (53%) trial participants and 51 (49%) non-participants, with most patients having more than five positive lymph nodes: 58 (79%) participants, 39 (76%) non-participants; P = 0.86. Bone metastases were found in 94% of patients in the participant group and 86% of patients in the non-participant group (P = 0.066), with most patients bearing 10 or more metastases: 58 (79%) participants and 39 (92%) non-participants. Some patients had metastases to the lungs (participants 5% vs non-participants 9.6%; P = 0.26) and to the liver (participants 6.5% vs non-participants: 14%; P = 0.07). Measurable disease (according to Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group 2 criteria [30]) was found in 37% of trial participants and 45% of non-participants (P = 0.47). Trial participants received more cycles of chemotherapy than non-participants (6 ± 1.2 vs 5 ± 1.2; P = 0.005). However, tumour response rates to docetaxel chemotherapy, defined by RECIST criteria [33], were not statistically different between the two groups (52% for participants and 31% for non-participants; P = 0.07).

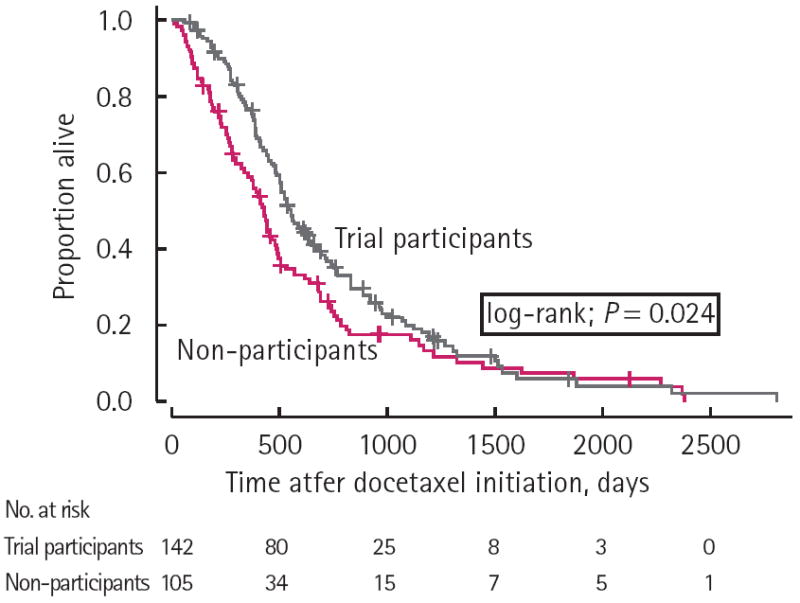

Patient age at the time of docetaxel initiation, Gleason score, primary treatment type, presence of lymph node metastases, and baseline platelet count, white blood cell count and serum creatinine were not significantly associated with overall survival in unadjusted analysis. Univariable analyses (Table 3) revealed a significantly higher risk of death for patients with lung metastases (hazard ratio (HR) 2.97; P < 0.001) and liver metastases (HR 1.65; P = 0.028), but these factors did not retain their significance when adjusted for study group and other clinical/pathological characteristics. Median overall survival on Kaplan–Meier analysis was found to be longer for trial participants compared with non-participants (21.3 months vs 17.3 months; P = 0.024) (Fig. 1).

TABLE 3.

Univariable analysis predictive of overall survival

| Variable | Categories | HR for death | 95% CI of HR | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study group | Trial participants (vs non-participants) | 0.73 | (0.551–0.959) | 0.024 |

| Age | Continuous | 1.01 | (0.996–1.03) | 0.15 |

| Primary treatment | Radiation alone (vs surgery ± radiation) | 1.19 | (0.883–1.59) | 0.26 |

| Number of chemotherapy cycles | Continuous | 0.91 | (0.866–0.954) | 0.0001 |

| Gleason score | 7 (vs ≤6) | 1.37 | (0.715–2.62) | 0.34 |

| 8–10 (vs ≤6) | 1.6 | (0.855–3.01) | 0.14 | |

| No. of hormonal therapies | Continuous | 0.94 | (0.78–1.13) | 0.51 |

| Bisphosphonate use | Yes (vs no) | 0.86 | (0.63–1.17) | 0.34 |

| ECOG Score | ≥1 (vs 0) | 1.63 | (1.12–2.39) | 0.011 |

| Pain score (0–10) | Continuous | 1.03 | (0.95–1.11) | 0.43 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | <12 (vs ≥12.1 g/dL) | 2.09 | (1.57–2.77) | <0.0001 |

| Albumin (U/L) | <3.8 (vs ≥3.9 U/L) | 0.65 | (0.45–0.91) | 0.014 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | <98 (vs ≥99 U/L) | 1.84 | (1.37–2.48) | <0.0001 |

| Platelet count (×109/L) | Continuous | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 0.12 |

| WBC count (×109/L) | Continuous | 1.00 | (1.00–1.00) | 0.66 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | Continuous | 1.49 | (0.98–2.25) | 0.059 |

| AST (U/L) | Continuous | 1.02 | (1.01–1.03) | <0.0001 |

| ALT (U/L) | Continuous | 1.00 | (0.99–1.01) | 1.00 |

| Presence of bone metastases | Yes (vs no) | 1.03 | (0.62–1.69) | 0.91 |

| No. of metastases (n) | Continuous | 1.33 | (1.06–1.68) | 0.015 |

| Presence of lymph node metastases | Yes (vs no) | 1.05 | (0.79–1.38) | 0.74 |

| No. of metastases (n) | >5 (vs ≤5) | 1.35 | (0.82–2.19) | 0.23 |

| Presence of lung metastases | Yes (vs no) | 2.97 | (1.76–5.02) | <0.0001 |

| No. of metastases (n) | >5 (vs ≤5) | 3.20 | (0.71–14.4) | 0.13 |

| Presence of liver metastases | Yes (vs no) | 1.65 | (1.06–2.57) | 0.028 |

| No. of metastases (n) | >5 (vs ≤5) | 1.37 | (0.52–3.55) | 0.52 |

| Presence of measurable disease | Yes (vs no) | 0.89 | (0.67–1.18) | 0.43 |

| Presence of objective tumour response | Yes (vs no) | 0.73 | (0.86–2.19) | 0.18 |

| Baseline (log) PSA | Continuous | 1.11 | (1.02–1.21) | 0.017 |

Please refer to Table 2 for percentages of patients in each subgroup. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ECOG, European Cooperative Oncology Group; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

FIG. 1.

Overall survival according to trial particiaption versus non-participation.

On multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression analyses (Table 4), trial participation status was found to be an independent predictor of survival with a significantly lower risk of death (HR 0.567; P = 0.027) noted for trial participants compared with non-participants. Patients with a baseline haemoglobin <12 g/dL (HR 1.628; P = 0.042) or an albumin level <3.8 U/L (HR 1.671; P = 0.046) in their initial measurement before the start of the first docetaxel treatment were at higher risk of death. In addition, a baseline (log) PSA level <4.7 (HR 0.37; P < 0.001) and an alkaline phosphatase level <98 U/L (HR 0.565; P = 0.019) were significantly associated with improved overall survival in multivariable analysis. Finally, patients who received at least five cycles of chemotherapy (HR 0.466; P < 0.001) also showed improved overall survival after adjustment for other factors.

TABLE 4.

Multivariable model predicting overall survival

| Variable | HR | 95% CI of HR | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study group: trial participants (vs non-participants) | 0.57 | (0.343–0.936) | 0.027 |

| Alkaline phosphatase: <98 (vs ≥ 99 U/L) | 0.57 | (0.350–0.911) | 0.019 |

| Albumin: <3.8 (vs ≥ 3.9 U/L) | 1.67 | (1.009–2.767) | 0.046 |

| Number of chemotherapy cycles: >5 (vs ≤ 5) | 0.47 | (0.297–0.733) | 0.0009 |

| Haemoglobin: <12 (vs ≥ 12.1 g/dL) | 1.63 | (1.017–2.606) | 0.042 |

| (log) PSA at baseline: <4.7 (vs ≥ 4.8) | 0.37 | (0.230–0.596) | <0.0001 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

DISCUSSION

Physicians and clinical researchers often assume the existence of empirical evidence in support of the benefit derived from participating in clinical trials. Indeed, there are obvious reasons why patients participating in clinical trials may derive benefits. Clinical trial participation provides access to newer, potentially active, drugs long before their approval and general availability. Even in cases where an experimental drug may not eventually become approved, some patients might still experience beneficial effects from an agent that would not have been received outside the clinical trial. However, there is also the possibility that the effect of a treatment received on clinical trials may be less efficacious or more toxic than standard therapy. Furthermore, participation in a trial may sometimes also result in a time delay until proven standard therapy is administered.

In several studies, patients were reported to have favourable outcomes just through participation in a clinical trial itself [13,21,34]. This phenomenon has been ascribed to the so-called ‘trial effect’ [21]. In a review, Braunholtz et al. [21] analysed primary data from several clinical trials that examined such trial effects, most of which were cancer trials, to investigate the existence of a potential positive effect on the outcome of participants (compared with non-participants) [21,34]. The authors could not find conclusive evidence of this, but assumed that it would be more likely that clinical trials have a positive rather than a negative effect on the outcome of participants. A variety of trial effects including improved routine care within a clinical trial (care effect), a specific way of treatment delivery (protocol effect), differences in patient compliance and/or clinician behaviour (Hawthorne effect) as the result of quality control and closer observation within clinical trials, as well placebo effects, may potentially lead to improved outcomes [13,21,34]. Another possibility is that patients who choose to participate in clinical trials might be inherently more adherent, ones who would leave no stone unturned to try every possible treatment option, including trial participation. However, this effect has not been investigated to date for men with mCRPC receiving first-line docetaxel-containing therapy either within or outside of a clinical trial [21].

The aim of the present study was to investigate whether treatment of mCRPC with chemotherapy regimens containing docetaxel received within the context of a clinical trial may lead to improved overall survival compared with receipt of the same chemotherapy agent (at the same dose and schedule) among patients who did not participate in a clinical trial. To this end, Kaplan–Meier analysis showed that survival was higher among participants compared with non-participants (21.3 months versus 17.3 months; P = 0.024). Furthermore, multivariable analyses revealed that trial participation status was an independent predictor of overall survival, with trial participants having a significantly lower risk of death compared with non-participants (HR 0.567; P = 0.027). The demonstration of improved survival among trial participants, even after adjusting for all available baseline demographic and clinical/pathological factors by multivariable analysis, was important, because the reasons for participating (or not participating) in a clinical trial were non-random (e.g. selection bias due to screen failure).

Some of the earliest reports that showed favourable survival outcomes for trial participants were published in the 1980s [35,36]. In one such study, Davis et al. [36] showed that patients with resected non-small-cell lung cancer had significantly better survival rates at 24 months on prospective clinical or investigational immunotherapy, chemotherapy and radiotherapy compared with non-participants (82% vs 50%; P < 0.001). By contrast, Tanai et al. analysed the characteristics and outcomes of patients with advanced gastric cancer that were treated as participants or non-participants of clinical trials [17]. The authors reported that there was no difference in clinical outcomes between participants and non-participants in their study populations. However, the number of trial participants in the study was disproportionately higher than non-participants, which might have skewed the outcomes.

Our current study also revealed that a baseline (log) PSA value <4.7 (HR 0.37; P < 0.001), as well as an alkaline phosphatase level <98 IU/L (HR 0.565; P = 0.019) were found to independently predict a better overall survival. Also, patients receiving five or more cycles of docetaxel chemotherapy had improved survival (HR 0.466; P = 0.009). Furthermore, a baseline haemoglobin <12 g/dL (HR 1.628; P = 0.042), and a serum albumin level <3.8 g/dL (HR 1.671; P = 0.046) conferred worse survival outcomes. These findings echo previous studies examining prognostic factors for survival in men receiving first-line docetaxel chemotherapy for mCRPC [37-39].

Our study has several limitations. This study was a non-randomized retrospective analysis of patients who participated in several clinical trials (each using first-line docetaxel chemotherapy) or who received standard docetaxel therapy at a single academic institution. None of the studies were designed to capture differences in outcomes and characteristics between trial participants and non-participants (i.e. comparing enrolled patients against ineligible patients or those failing screening assessments). In the process of accrual, differences in selection criteria between different clinical trials and also in comparison to patients who received standard therapy may have introduced bias. However, our results have been derived by a multivariable Cox proportional hazards analysis through which we have accounted for such baseline discrepancies that might have affected survival outcomes. Also, the potential argument that trial participants as a whole may have had superior survival because of the ‘experimental’ therapy received in conjunction with docetaxel can be refuted on the grounds that none of these trials reported a statistically superior survival outcome for the investigational arm compared with the standard arm, although it is potentially possible that the collective effect of small benefits across trials may have been amplified by this combined analysis. Another limitation of our study is that we did not have access to demographic information such as education, employment status and marital status, which could potentially influence trial participation. Furthermore, patients who received chemotherapy while not enrolled in a clinical trial were treated following their clinician’s practices, which might have been different from the treatment protocols used in the various clinical trials (e.g. frequency and type of imaging, laboratory tests). Finally, there was no control over additional and further therapies in patients who received standard therapy or came off study, and information about subsequent therapies was not available in either study group.

In conclusion, we investigated the putative beneficial effect of clinical trial participation on survival outcomes of patients with mCRPC who were treated with first-line docetaxel-containing chemotherapy. For the first time, we show that after accounting for potential baseline inequalities, participation in a clinical trial may in itself provide an inherent survival advantage to these patients. These findings need to be further evaluated in a prospective fashion.

What’s known on the subject? and What does the study add?

Previous studies have reported better outcomes in cancer patients that enrolled in clinical trials, suggesting that trial participation in itself might be beneficial.

We investigated the potential positive effect of clinical trial participation on survival outcomes of patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer who were treated with first-line docetaxel-containing chemotherapy. After accounting for potential baseline inequalities, participation in a clinical trial itself was associated with significantly longer overall survival in these patients.

Abbreviations

- mCRPC

metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer

- ECOG

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None declared.

Study Type - Prognosis (case series)

Level of Evidence 4

References

- 1.Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1502–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petrylak DP, Tangen CM, Hussain MH, et al. Docetaxel and estramustine compared with mitoxantrone and prednisone for advanced refractory prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1513–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Molina A, et al. Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1995–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1147–54. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61389-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sonpavde G, Attard G, Bellmunt J, et al. The role of abiraterone acetate in the management of prostate cancer: a critical analysis of the literature. Eur Urol. 2011;60:270–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2011;59:572–83. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beltran H, Beer TM, Carducci MA, et al. New therapies for castration-resistant prostate cancer: efficacy and safety. Eur Urol. 2011;60:279–90. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:411–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antonarakis ES, Armstrong AJ. Emerging therapeutic approaches in the management of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2011;14:206–18. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2011.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antonarakis ES, Eisenberger MA. Expanding treatment options for metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2055–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1102758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joniau S, Abrahamsson PA, Bellmunt J, et al. Current vaccination strategies for prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2012;61:290–306. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanai C, Nokihara H, Yamamoto S, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer who declined to participate in randomised clinical chemotherapy trials. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1037–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lara PN, Jr, Higdon R, Lim N, et al. Prospective evaluation of cancer clinical trial accrual patterns: identifying potential barriers to enrollment. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1728–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corrie P, Shaw J, Harris R. Rate limiting factors in recruitment of patients to clinical trials in cancer research: descriptive study. BMJ. 2003;327:320–1. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7410.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Go RS, Frisby KA, Lee JA, et al. Clinical trial accrual among new cancer patients at a community-based cancer center. Cancer. 2006;106:426–33. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanai C, Nakajima TE, Nagashima K, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with advanced gastric cancer who declined to participate in a randomized clinical chemotherapy trial. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7:148–53. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2010.000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jenkins V, Fallowfield L. Reasons for accepting or declining to participate in randomized clinical trials for cancer therapy. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:1783–8. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albrecht TL, Eggly SS, Gleason ME, et al. Influence of clinical communication on patients’ decision making on participation in clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2666–73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright JR, Whelan TJ, Schiff S, et al. Why cancer patients enter randomized clinical trials: exploring the factors that influence their decision. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4312–18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.01.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Braunholtz DA, Edwards SJ, Lilford RJ. Are randomized clinical trials good for us (in the short term)? Evidence for a ‘trial effect’. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:217–24. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00305-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly WK, Halabi S, Carducci MA, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial comparing docetaxel, prednisone, and placebo with docetaxel, prednisone, and bevacizumab in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC): survival results of CALGB 90401. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1534–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.4767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinibaldi VJ, Elza-Brown K, Schmidt J, et al. Phase II evaluation of docetaxel plus exisulind in patients with androgen independent prostate carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2006;29:395–8. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000225411.95479.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beer TM, Eilers KM, Garzotto M, Egorin MJ, Lowe BA, Henner WD. Weekly high-dose calcitriol and docetaxel in metastatic androgen-independent prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:123–8. doi: 10.1200/jco.2003.05.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Savarese DM, Halabi S, Hars V, et al. Phase II study of docetaxel, estramustine, and low-dose hydrocortisone in men with hormone-refractory prostate cancer: a final report of CALGB 9780. Cancer and Leukemia Group B. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2509–16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.9.2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jameson MB, Thompson PI, Baguley BC, et al. Phase I/II Trials Committee of Cancer Research UK. Clinical aspects of a phase I trial of 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid (DMXAA), a novel antivascular agent. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:1844–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin J, Sinibaldi VJ, Carducci MA, et al. Phase I trial with a combination of docetaxel and (153)Sm-lexidronam in patients with castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2011;29:670–5. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higano C, Saad F, Somer B, et al. A phase III trial of GVAX immunotherapy for prostate cancer versus docetaxel plus prednisone in asymptomatic, castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) Genitourinary Cancers Symposium. 2009 Abstract LBA150. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hudes GR, Tagawa S, Whang Y, et al. A phase I study of CNTO 328, an anti-interleukin (IL)-6 monoclonal antibody combined with docetaxel (T) in subjects with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) Genitourinary Cancers Symposium. 2009 Abstract 164. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scher HI, Halabi S, Tannock I, et al. Design and end points of clinical trials for patients with progressive prostate cancer and castrate levels of testosterone: recommendations of the Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1148–59. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dinse GE, Lagakos SW. Nonparametric estimation of lifetime and disease onset distributions from incomplete observations. Biometrics. 1982;38:921–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karrison T. Confidence intervals for median survival times under a piecewise exponential model with proportional hazards covariate effects. Stat Med. 1996;15:171–82. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960130)15:2<171::AID-SIM146>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peppercorn JM, Weeks JC, Cook EF, Joffe S. Comparison of outcomes in cancer patients treated within and outside clinical trials: conceptual framework and structured review. Lancet. 2004;363:263–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15383-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Link MP, Goorin AM, Miser AW, et al. The effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on relapse-free survival in patients with osteosarcoma of the extremity. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:1600–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198606193142502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis S, Wright PW, Schulman SF, et al. Participants in prospective, randomized clinical trials for resected non-small cell lung cancer have improved survival compared with nonparticipants in such trials. Cancer. 1985;56:1710–18. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19851001)56:7<1710::aid-cncr2820560741>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Halabi S, Small EJ, Kantoff PW, et al. Prognostic model for predicting survival in men with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1232–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Armstrong AJ, Garrett-Mayer E, de Wit R, Tannock I, Eisenberger M. Prediction of survival following first-line chemotherapy in men with castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:203–11. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Armstrong AJ, Garrett-Mayer ES, Yang YC, de Wit R, Tannock IF, Eisenberger M. A contemporary prognostic nomogram for men with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer: a TAX327 study analysis. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:6396–403. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]