Abstract

Our previous studies demonstrated that specific polyamine analogues, oligoamines, down-regulated the activity of a key polyamine biosynthesis enzyme, ornithine decarboxylase (ODC), and suppressed expression of estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) in human breast cancer cells. However, the mechanism underlying the potential regulation of ERα expression by polyamine metabolism has not been explored. Here, we demonstrated that RNAi-mediated knockdown of ODC (ODC KD) down-regulated the polyamine pool, and hindered growth in ERα-positive MCF7 and T47D and ERα-negative MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. ODC KD significantly induced the expression and activity of the key polyamine catabolism enzymes, spermine oxidase (SMO) and spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase (SSAT). However, ODC KD-induced growth inhibition could not be reversed by exogenous spermidine or overexpression of antizyme inhibitor (AZI), suggesting that regulation of ODC on cell proliferation may involve the signaling pathways independent of polyamine metabolism. In MCF7 and T47D cells, ODC KD, but not DFMO treatment, diminished the mRNA and protein expression of ERα. Overexpression of antizyme (AZ), an ODC inhibitory protein, suppressed ERα expression, suggesting that ODC plays an important role in regulation of ERα expression. Decrease of ERα expression by ODC siRNA altered the mRNA expression of a subset of ERα response genes. Our previous analysis showed that oligoamines disrupt the binding of Sp1 family members to an ERα minimal promoter element containing GC/CA-rich boxes. By using DNA affinity precipitation and mass spectrometry analysis, we identified ZBTB7A, MeCP2, PARP-1, AP2, and MAZ as co-factors of Sp1 family members that are associated with the ERα minimal promoter element. Taken together, these data provide insight into a novel antiestrogenic mechanism for polyamine biosynthesis enzymes in breast cancer.

Keywords: Polyamines, Ornithine decarboxylase, Estrogen receptor α, Antizyme, Breast cancer

Introduction

Enhanced levels of key polyamine synthesis enzyme ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) activity have been detected in several solid tumors [1, 2]. Studies have demonstrated the important roles of ODC in breast tumor development and metastasis [3, 4]. In estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) positive breast cancer cells, estradiol up-regulates ODC activity and increases the polyamine levels, which promotes cell proliferation [5]. Growth inhibition of MCF-7 cells by tamoxifen is associated with the down-regulation of polyamine biosynthesis [6]. ODC-overexpressing breast cancer cells and specimens showed suppressed expression of collagen and endostatin that promotes the invasion and metastasis of tumor cells [7]. These results suggest the importance of polyamine action in breast tumor progression and underscore the rationale of targeting polyamine metabolism as a potential intervention for breast cancer therapeutics.

Our studies have shown that long chain polyamine analogues, oligoamines, significantly down-regulate ODC activity, induce the polyamine catabolismenzyme, SSAT, and decrease the natural polyamine pools [8, 9]. Importantly, our data demonstrated that oligoamines effectively suppress expression and the ligand-dependent transcriptional activity of ERa, a principal determinant of breast cell growth [9]. Our studies also suggested that Sp1 transcription factor family members were involved in oligoamine-regulated ERa expression [9]. In this study, we designed experiments to address two important issues: (1) What is the role of ODC in regulating breast tumor cell growth? (2) What are the mechanisms by which ODC regulates the ERα gene transcription? To answer these questions, we define in depth the mechanisms of regulation of polyamine biosynthesis pathway on breast tumor cell growth and ERα expression. The results from these studies suggest that ODC plays an important role in the regulation of ERa expression and represents a potential therapeutic target in human breast cancer cells.

Materials and methods

Reagents and cell culture condition

DFMO was obtained from Dr. Patrick Woster (Medical University of South Carolina). MCF7, T47D and MDA-MB-231 were cultured in DMEM medium (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) supplemented with 5 % FBS at 37 °C with 5 % C02.

siRNA transfection

Oligomers of ODC siRNAl (AACCCAGCGUUGGA CAAAUAC) and siRNA2 (AAGGAUGCCUUCUAU GUGGCA) were synthesized using Silencer siRNA construction kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) and transfected into cells with Lipofectamine RNAimax (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 10 nM concentration.

Analysis of intracellular polyamine level and polyamine enzyme activity

The intracellular polyamine levels and ODC activity of siRNA or DFMO-treated and untreated cells were measured using cellular extracts as described previously [10, 11]. The enzyme activities of spermine oxidase (SMO) were assayed as described previously by using 250 µM spermine and N -acetylspermine, respectively, as the substrate [12].

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer and 20 µg of total proteins were fractionated on NuPAGE gels and transferred onto PVDF membranes. Primary antibodies against ERα, ODC and other target proteins were purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA). Antibodies against AZI and AZ were kindly provided by Dr. Chaim Kahana at Weizmann Institute. A semi-quantification Odyssey Infrared Detection system was used to quantify the protein expression. Actin protein was blotted as a control.

Reverse transcription quantification PCR

Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Kit (Invitrogen). Reverse transcription was carried out using Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) [13]. PCR primer sets were as follows: ODC forward: 5′ATGTTGCATCAGCT TTCACG3′ and reverse 5′ACTCTCCCAGGCACAAGA CA3′. SSAT forward: 5′-GACCCCTGAAGGACATAG CA-3′ and reverse: 5′-CCGAAGCACCTCTTCTTTTG-3′; SMO forward: 5′-CACGTGATTGTGACCGTTTC-3′ and reverse: 5′-TGGGTAGGTGAGGGTACAGTC-3′; GAP-DH forward: 5′GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTC3′ and reverse:5′GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTTC3′. A single-color MyIQ real-time PCR machine was used to detect gene expression.

PCR array of gene expression

Human breast cancer RT Profiler PCR array (SABiosciences, Frederick, MD) profiles the expression of 84 genes commonly involved in regulation of breast carcinogenesis. After ODC siRNA transfection, cDNA samples were synthesized and loaded onto the array, and amplification was performed as recommended by the manufacturer.

Stable expression of antizyme (AZ) or antizyme inhibitor (AZI)

Cells were transfected with bicistronic vector (pERIRES-E) or AZ containing construct (pERIRES-AZ) or AZI containing construct (from Dr. Chaim Kahana, Weizmann Institute) using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen). The trans-fected cells were selected with 0.05 g/ml puromycin and surviving single cell colonies were expanded and assayed for expression of AZ or AZI through western blotting.

DNA affinity precipitation assays (DAPA) and mass spectrometry analysis

5’-Biotin end-labeled sense and antisense oligonucleotides corresponding to the wild-type (5′-CGTGCGCCCCCGCCCCCTGGC-3′) or mutant (5′-CGTatctgcagctCTGGC-3′) Sp1 binding sites at the ERα promoter were custom made by GeneProbe Technology, Inc. (Gaithersburg, MD). The oligomers were annealed and gel purified. Pre-cleared nuclear extracts were incubated with 0.125 nM of wild-type or mutant biotinylated probes in binding buffer (100 mM KCl,12 mM HEPES pH 7.9,4 mM Tris-HCl, 5 % glycerol, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol) for 1 h at 4 °C. The DNA-protein complexes were then incubated with 40 µl Tetralink avidin resin for 1 h at 4 °C. After heat denaturation, the proteins were fractionated on SDS-PAGE and silver stained. The silver-stained bands that appeared from the complex of wide-type oligonucleotides, not the mutant ones, were excised from the gel, and digested trypsin. Tryptic digests were loaded onto fused silica capillary column and separated with 80 % acetonitrile/0.5 % acetic acid and then loaded into an LCQ Deca XP ion trap mass spectrometer and analyzed at the Johns Hopkins proteomic core facility.

Results

ODC KD down-regulated intracellular polyamines and induced expression of SMO and SSAT

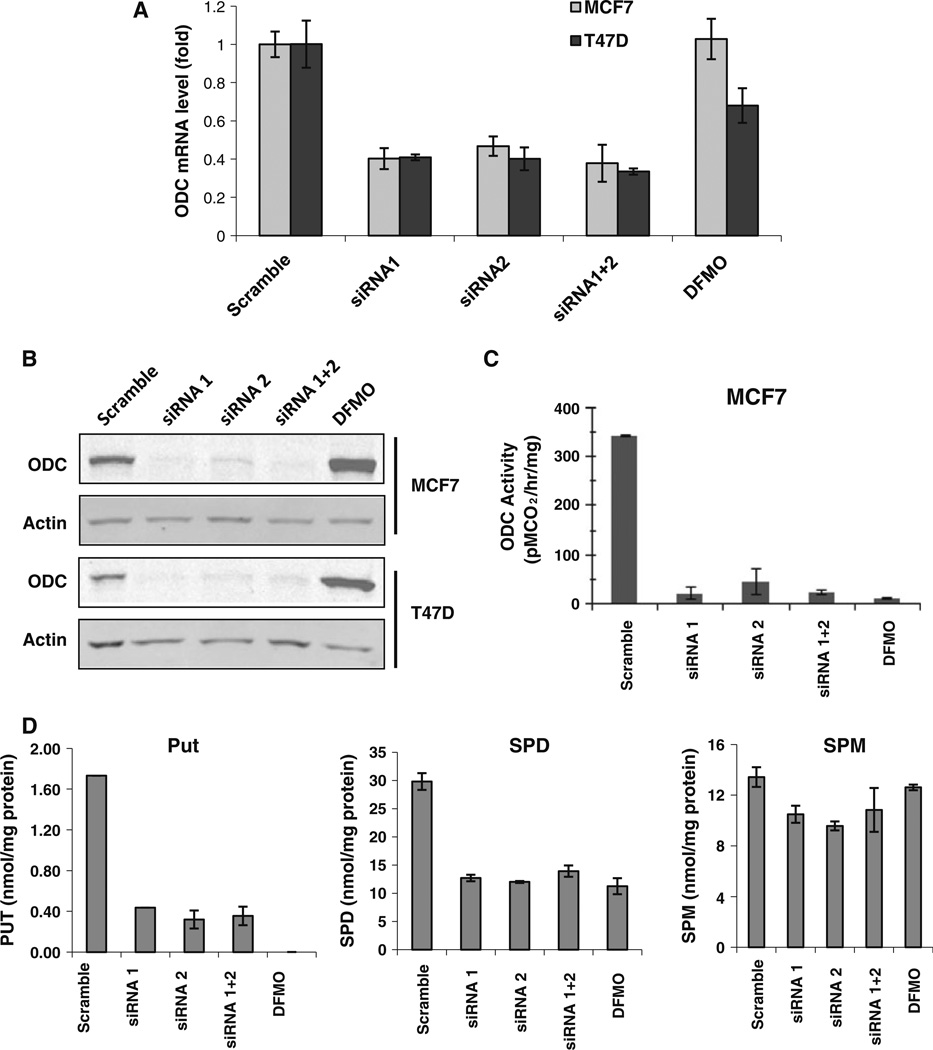

Treatment with ODC siRNA1 or siRNA2, or the combination decreased ODC mRNA expression in both MCF7 and T47D cells by ∼ 60 % (Fig. 1a) and led to significant decrease of ODC protein expression (Fig. 1b) and enzymatic activity (Fig. 1c). Intracellular putrescine and spermidine levels were significantly decreased by both ODC KD and inhibitor, DFMO, whereas spermine level was decreased in the ODC KD cells but not in DFMO-treated cells (Fig. 1d).

Fig. 1.

ODC siRNA down-regulated polyamine biosynthesis. a Cells were transfected with ODC siRNA or treated with 5 mM DFMO for 24 h. qPCR was performed to measure the mRNA level of ODC. b After transfection, cells were harvested and analyzed by immunoblots for expression of ODC. c ODC activity was measured after siRNA transfection or 5 mM DFMO treatment. d After siRNA transfection, intracellular polyamine levels were measured

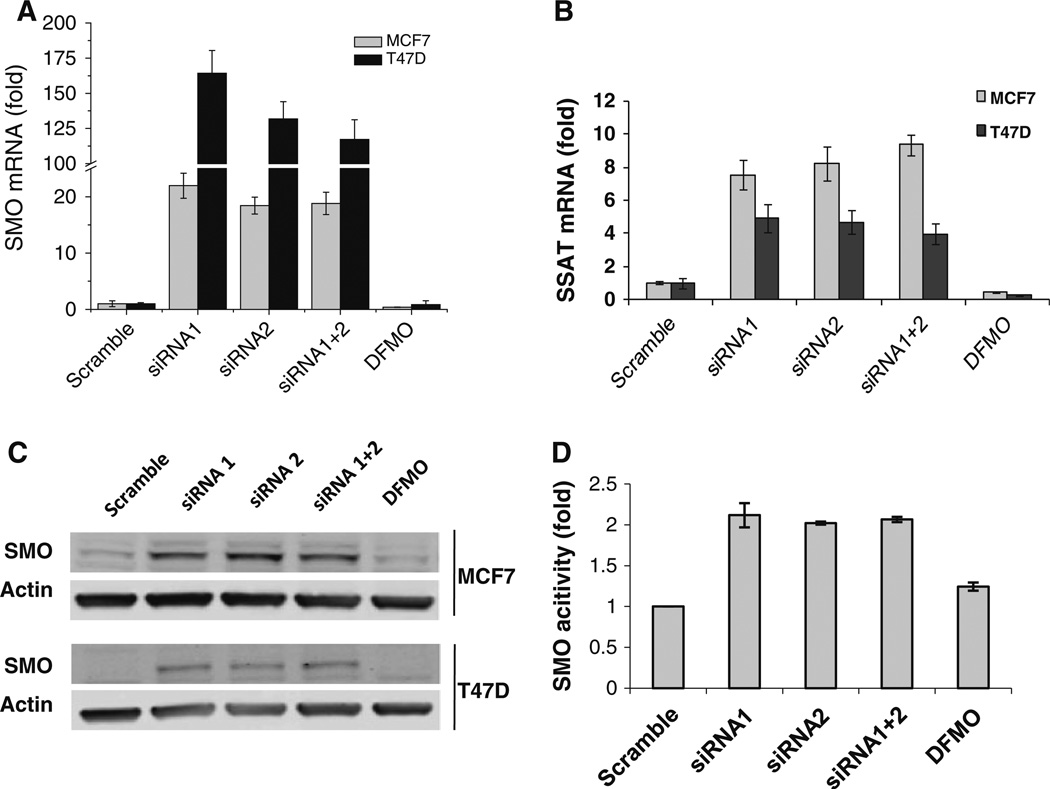

To address whether ODC KD-mediated gene silencing affects the activities of polyamine catabolic enzymes, the mRNA and protein expression of SMO and SSAT were assessed. ODC siRNA transfection induced mRNA expression of both SMO and SSAT (Fig. 2a, b). Induction of SMO mRNA expression led to an increase of SMO protein expression and more than twofold of increase of enzymatic activity (Fig. 2c, d). However, treatment with DFMO exerted marginal effect on either expression or activity of both SSAT and SMO, suggesting that loss of ODC protein rather than simple blockade of enzymatic activity leads to a more significant impact on activity of polyamine catabolism enzymes.

Fig. 2.

ODC KD-induced expression and activity of SMO and SSAT. SMO (a) and SSAT (b) mRNA levels in MCF7 and T47D cells were measured by qPCR after ODC siRNA transfection. c Western blotting analysis of SMO in MCF7 and T47D cells. d SMO activity was measured using methods as described in “Materials and methods”

ODC KD inhibited growth and induced apoptosis

Treatment with ODC siRNA 1 or siRNA 2 or the combination for 48 h significantly blocked proliferation of MCF7 and T47D cells, whereas DFMO treatment failed to alter growth rate (Fig. 3a). We next determined whether activity of apoptosis-regulatory proteins is involved in the mediation of ODC siRNA-induced cell death. As shown in Fig. 3b, ODC siRNA treatment induced Caspase 9 activation and PARP cleavage in both MCF7 and T47D cells without changing the expression of Fas-L, Caspase 8, Bax, or BCL-2.

Fig. 3.

ODC KD inhibits cell growth and induces apoptosis. a After transient siRNA treatment for 48 h, cells were detached by trypsinization and counted. b Equal amounts (20 µg/well) of whole-cell extracts were fractionated and immunoblotted with antibodies for apoptosis related proteins as indicated

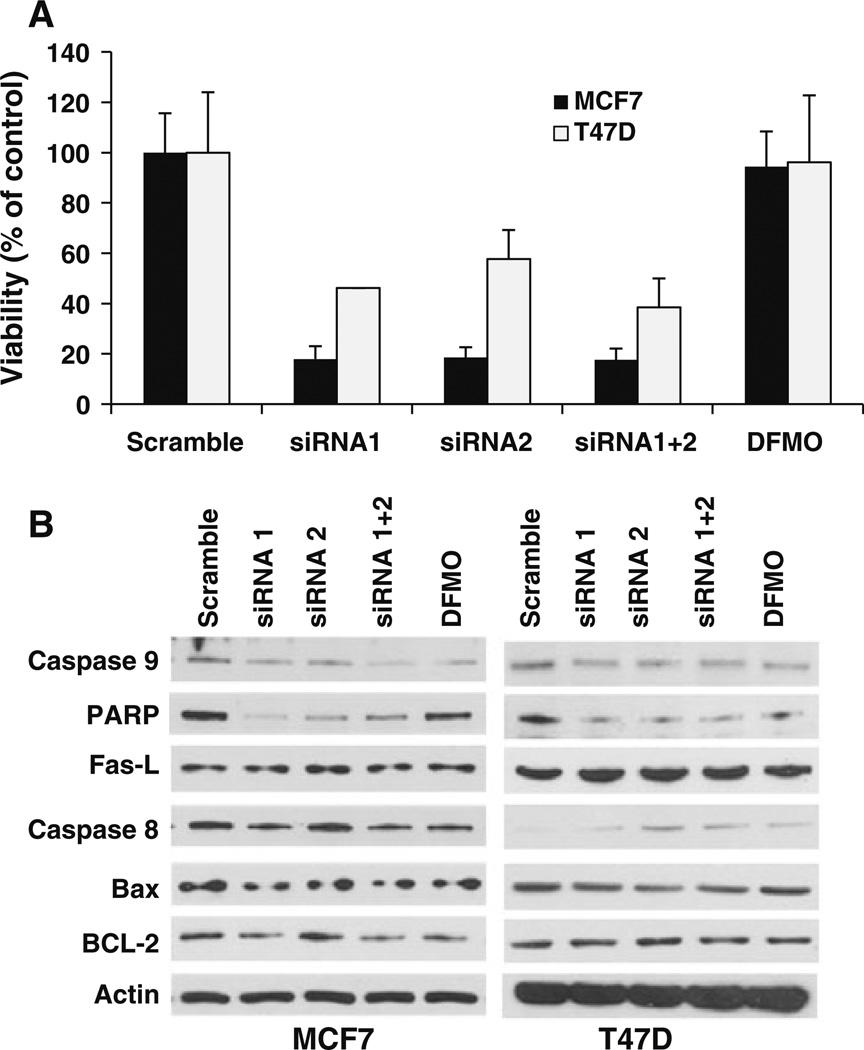

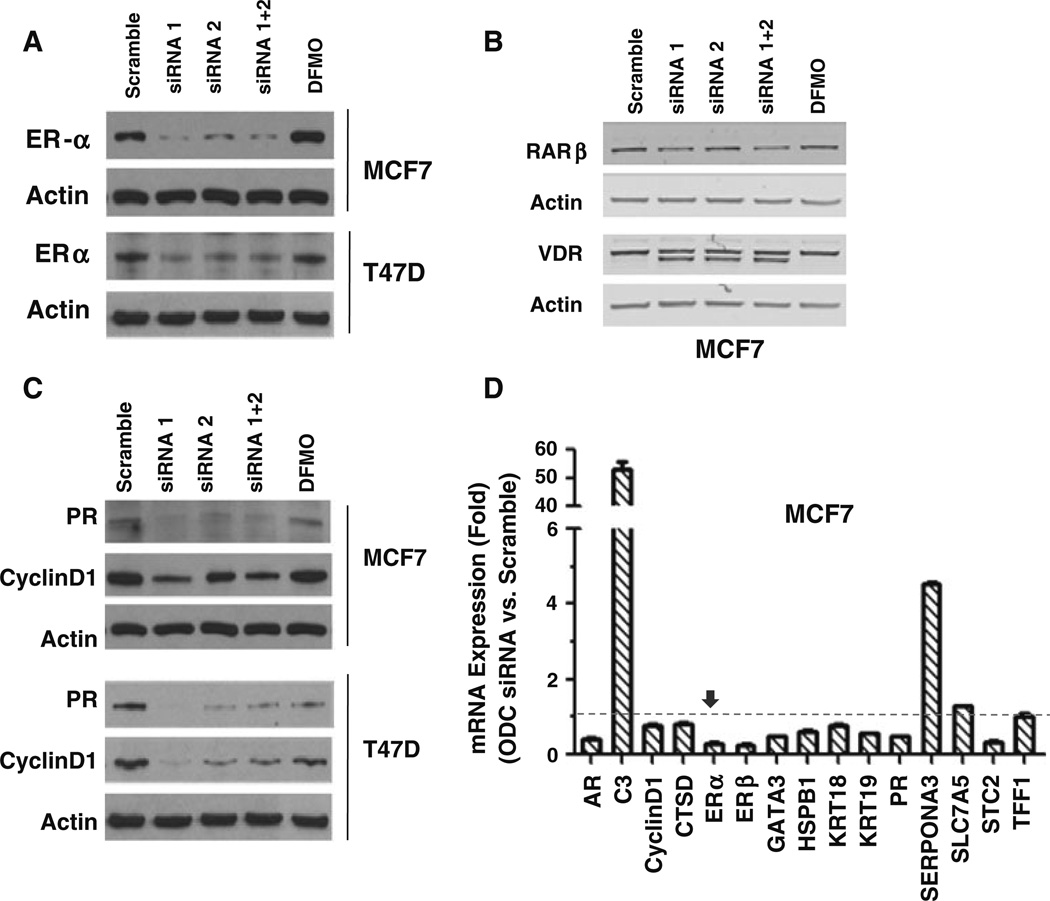

ODC is involved in regulation of ERα expression and activity

To investigate the potential role of ODC in regulation of ERα expression and activity, western blot was performed to assess the protein expression of ERα in ODC KD cells and showed that ODC KD inhibited the ERα protein expression in both MCF-7 and T47D cells (Fig. 4a), whereas the protein expression of other steroid receptors such as retinoic acid receptor β (RARβ) and vitamin D receptor (VDR) were not affected by ODC KD (Fig. 4b). Further, the expression of two ERα-regulated genes, progesterone receptor (PR) and cyclin D1 was also inhibited by ODC KD, suggesting that ODC depletion may specifically target ERα and its downstream genes (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4.

Effects of ODC KD on expression and activity of ERα. Cells were transfected with scramble control or ODC siRNA or treated with 5 mM DFMO. a Immunoblot with anti-ERα antibody was performed and analyzed. b Immunoblot analysis of the protein expression level of RARβ and VDR. c Immunoblot analysis of the expression level of PR and cyclin D1 proteins. d The mRNA expression of ERα response genes in scramble and ODC siRNA treated cells was analyzed using PCR array

Next, we investigated the effect of ODC KD on mRNA expression of ERα and its response genes using the breast cancer RT Profiler PCR array. As shown in Fig. 4d, depletion of ODC significantly decreased ERα mRNA expression, suggesting that down-regulation of ERα protein expression by ODC KD is caused by transcriptional repression. Further analysis showed that ODC KD decreased the mRNA expression of a subset of important growth-related genes that are associated with the ERα signaling pathway, including cyclin D1 (CCND1), GATA-binding protein 3 (GATA3), PR, heat shock protein beta-1(HSPB-1), Stanniocalcin 2 (STC2), and Keratin 18 and 19 (KRT18 and 19), etc. Interestingly, expression of ERβ was also found to be inhibited by ODC depletion, suggesting a broad effect of ODC activity in regulation of expression of ER family members. In contrast, mRNA expression of complement component 3 (C3) and serine peptidase inhibitor A3 (SERPINA3) was induced by ODC KD. Taken together, these results indicate that activity of ODC is extensively involved in regulation of activity of ERα and its downstream target genes in breast cancer cells.

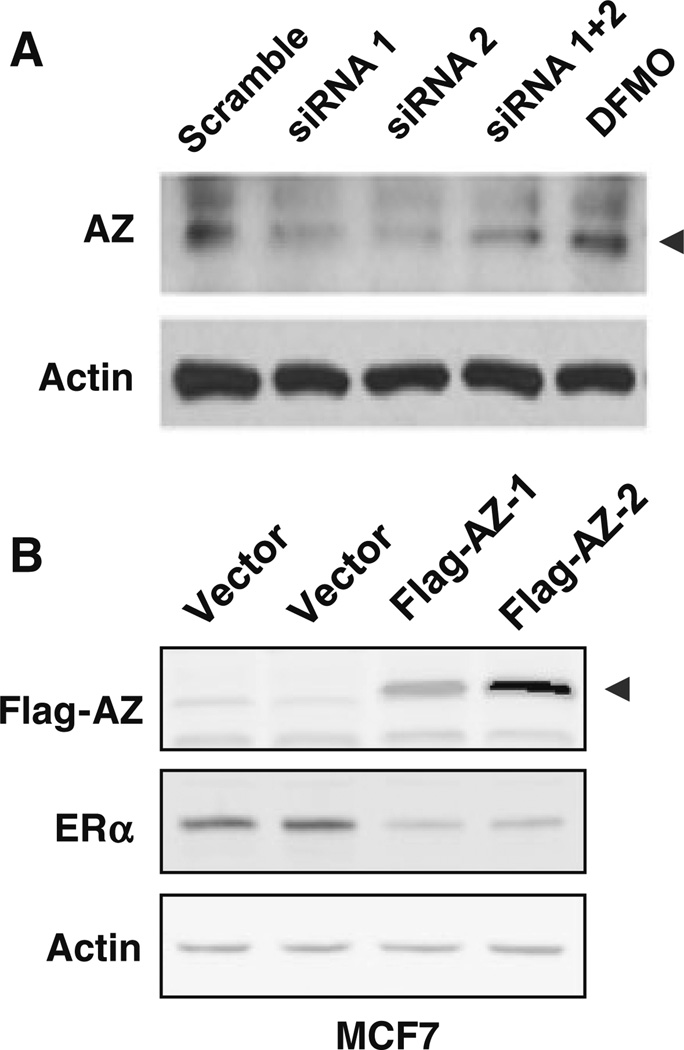

Antizyme (AZ) binds to ODC and facilitates the degradation of AZ–ODC complex by the 26S proteasome in a non-ubiquitin-dependent manner [14, 15]. In this study, we investigated if AZ is involved in regulation of ERα expression. We observed that ODC KD slightly decreased AZ protein expression in MCF7 cells (Fig. 5a). Overexpression of AZ by pERIRES-AZ plasmid diminished ERα expression in both AZ-overexpressing clones (MCF7-Flag-AZ-1 and MCF7-Flag-AZ-2) (Fig. 5b), suggesting that binding and elimination of ODC by AZ leads to a similar result as ODC KD.

Fig. 5.

Role of antizyme in ODC regulated ERα expression. a Immunoblot analysis of AZ protein in MCF7 and T47D cells transiently transfected with ODC siRNA. b Flag-tagged AZ was stably expressed in MCF7 cells. ERα protein level was detected by immunoblot

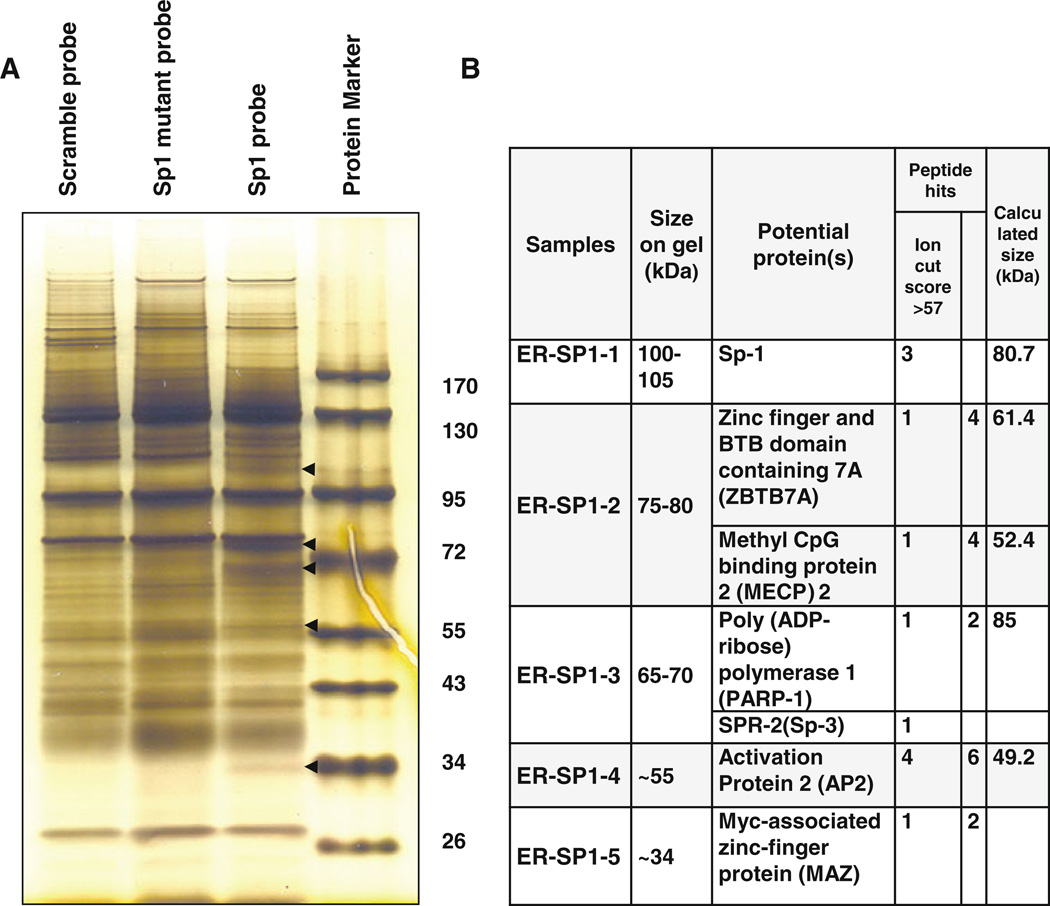

Identification of multi-protein complex at ERα minimal promoter

Our previous analysis showed that oligoamines dramatically inhibited the ERα promoter transcriptional activity within the −245 to −182 bp region, which contains the E, GC, and C/A rich boxes of binding sites for Sp1 transcription factor family [9]. To identify and monitor the recruitment of factors at the ER minimal promoter that are associated with Sp1 family, DAPA and mass spectrometry were performed. Five unique bands were recovered from wild-type probes which are absent from mutant counterparts (Fig. 6a). By using mass spectrometry, the following proteins were identified from recovered samples: Specificity protein 1 and 3 (Sp1 and Sp3), zinc finger and BTB domain containing 7A (ZBTB7A), methyl CpG-binding protein 2 (MeCP2), poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase 1 (PARP-1), transcription activation protein 2 (AP-2), and Myc-associated zinc-finger protein (MAZ) (Fig. 6b). The identification of these important factors suggests the likelihood that suppression of ERα mRNA expression by interference with polyamine metabolism may occur through disruption of the highly coordinated interaction between these regulatory factors at ERα promoter.

Fig. 6.

Identification of multi-protein complex at ERα minimal promoter element. a MCF7 cells were harvested and DNA affinity precipitation assay (DAPA) was performed. b The mass spectrometry analysis was carried out to identify factors that bind to ERα minimal promoter element

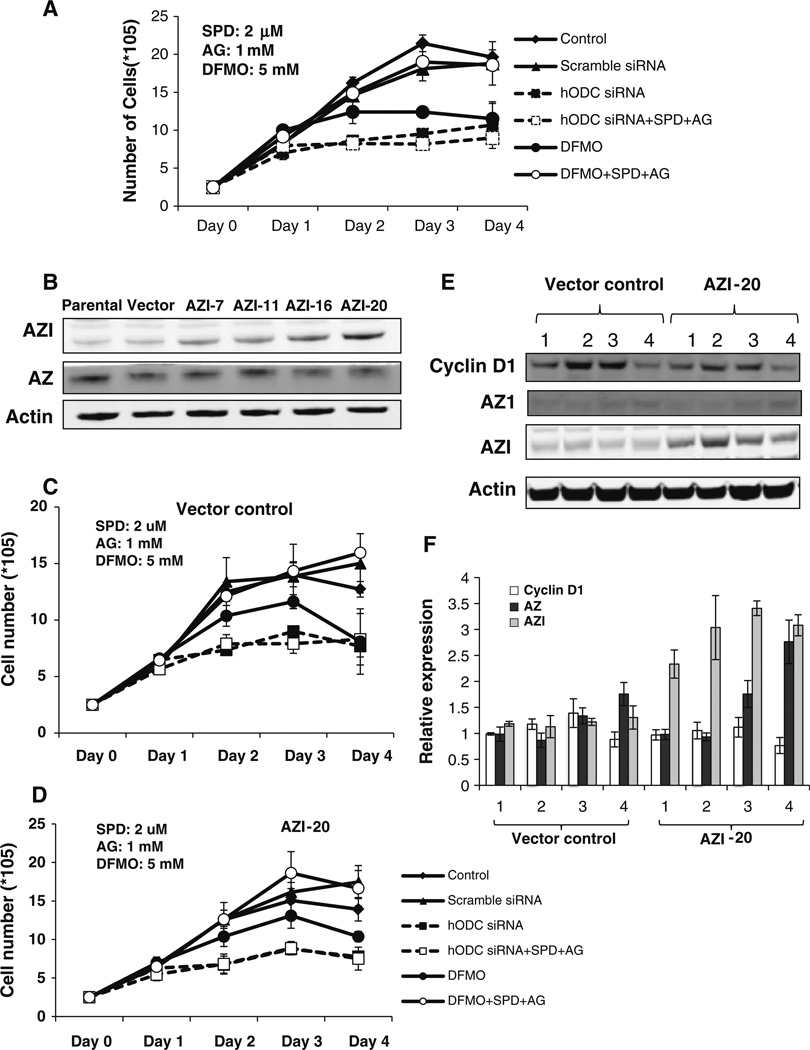

Role of AZI in regulation of ODC KD-induced growth inhibition

Since breast cancer is a highly heterogeneous disease, we further investigated and compared the effect of ODC on growth in ERα negative breast cancer cells. Both ODC siRNA and DFMO treatment in ERα negative MDA-MB-231 cells resulted in cell growth inhibition (Fig. 7a) and depletion of intracellular spermidine level by 85 % (Table 1). The addition of a lower concentration of exogenous spermidine (2 µM) partially restored the intracellular spermidine reduced by ODC KD, whereas higher concentration of spermidine (5 µM) fully restored the spermidine (Table 1). In contrast to ODC siRNA treatment, DFMO treatment-induced depletion of spermidine was only partially restored by a high concentration of spermidine (5 µM) without changing putrescine and spermine levels (Table 1). Interestingly, exogenous spermidine could not rescue ODC KD-mediated growth inhibition, but reversed growth inhibition caused by DFMO treatment (Fig. 7a). These data suggest the possibility that the loss of ODC protein may induce cell growth inhibition through polyamine independent pathways in addition to its regulation of polyamine metabolism. To validate this hypothesis, MDA-MB-231 cells were stably transfected with antizyme inhibitor (AZI) to examine if AZI could counter the effects of ODC siRNA. AZI is a protein highly similar to ODC. AZI binds to ODC–AZ and stabilizes ODC structure, thus inhibiting AZ-mediated ODC degradation [16]. Clone AZI-20 expressed the highest level of AZI and overexpression reduced protein expression of AZ as expected (Fig. 7b). However, AZI did not counter the inhibitory effect of ODC siRNA on cell growth (Fig. 7c). Moreover, AZI has also been reported to bind to and stabilize cyclin D1 [17]. Therefore, we investigated the effect of AZI overexpression on cyclin D1 stabilization. Overexpression of AZI failed to alter cyclin D1 protein expression in MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 7d, e). Taken together these data suggest that the ODC–AZ complex, or the ODC protein itself, may regulate breast tumor cell growth through both polyamine-dependent and independent pathways.

Fig. 7.

Effect of AZI on ODC KD-mediated growth inhibition. a MDA-MB-231 cells were transiently transfected with scramble or ODC siRNA or treated with 5 mM DFMO with or without 2 µM spermidine and 1 mM aminoguanidine (AG). Total cell numbers were counted at the indicated time points. b MDA-MB231 cells were stably transfected with pEFIRES-P (vector) or pEFIRES-AZI plasmids. Single clones were analyzed for AZI and AZ expression by immunoblots. c Vector control and AZI overexpressing clone AZI-20 were transiently transfected with ODC siRNA or treated with 5 mM DFMO. Total cell numbers were counted in the presence or absence of spermidine and AG. d Vector control and AZI-20 cells were transiently transfected with ODC siRNA. Cell lysate was analyzed for cyclin D1, AZ1 and AZI expression by immunoblots. Numbers 1, 2, 3, and 4 represent untreated, scramble siRNA transfected, hODC siRNA transfected and DFMO (5 mM)-treated cells respectively. e Histograms represent the mean protein expression levels of three determinations relative to actin ± SD as determined by quantitative immunoblotting

Table 1.

Effects of ODC knockdown on polyamine uptake in MDA-MB-231 cells. Intracellular polyamine levels were determined as described in “Materials and methods”. Values represent the means of duplicate determinations

| Treatment | Polyamine concentration (nmol/mg protein) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Putrescine | Spermidine | Spermine | |

| Untreated | 1.6 ± 0.55 | 6.4 ± 0.43 | 5.3 ± 1.96 |

| Scramble siRNA | 1.2 ± 0.76 | 4.7 ± 1.17 | 5.8 ± 1.05 |

| Scramble siRNA + SPD 2 µM + AG 1 mM | 0.9 ± 0.04 | 4.3 ± 1.05 | 7.4 ± 0.61 |

| Scramble siRNA + SPD 5 µM + AG 1 mM | 1.2 ± 0.28 | 4.8 ± 0.27 | 7.9 ± 1.25 |

| ODC siRNA | 0 ± 0.01 | 0.9 ± 0.13 | 11.0 ± 0.44 |

| ODC siRNA + SPD 2 µM + AG 1 mM | 0 ± 0.01 | 2.4 ± 0.61 | 11.0 ± 0.6 |

| ODC siRNA + SPD 5 µM + AG 1 mM | 0 ± 0.01 | 13.1 ± 2.49 | 9.8 ± 1.08 |

| DFMO 5 mM | 0 ± 0.01 | 0.4 ± 0.03 | 5.8 ± 0.42 |

| DFMO 5 mM + SPD 2 µM + AG 1 mM | 0 ± 0.01 | 0.4 ± 0.05 | 5.6 ± 1.05 |

| DFMO 5 mM + SPD 5 µM + AG 1 mM | 0 ± 0.01 | 3.1 ± 0.28 | 4.1 ± 0.27 |

Discussion

In recent work, we have shown that long chain polyamine analogues, oligoamines, affect expression and activity of a subset of important growth-related genes, whose activity is closely involved in cell cycle regulation and apoptosis [8, 18–20]. ERα is among these genes, and its expression and activity are significantly suppressed by oligoamines [9]. In this study, we observed that ERα mRNA and protein expression were markedly suppressed by ODC siRNA. Importantly, we demonstrated that loss of ODC altered the expression of a subset of the important growth-related genes that are associated with the ERα signaling pathway. These observations suggest that ERα is an important target of ODC. This hypothesis was further supported by the finding that overexpression of AZ inhibits ERα expression and exogenous spermine can reverse oligoamine-induced down-regulation of ERα protein expression (data not shown).

Our demonstration that loss of ODC suppresses ERα mRNA expression provides new evidence that the polyamine biosynthetic enzyme plays a role in regulation of transcription of ERα gene. However, inhibition of ODC activity by its inhibitor DFMO was not able to change ERα expression, implying that down-regulation of intracellular polyamine levels alone may not be sufficient to inhibit ERα expression. It is possible that the effect of ODC on ERα expression involves the collaboration between intracellular polyamines and factors that are independent of polyamine metabolism. This study identified a group of important proteins that are likely associated with Sp1 at the ERα minimal promoter element whose activity is disrupted by polyamine analogues. For example, ZBTB7A is a protooncogene and transcription factor which interacts with other transcription factors, such as Sp1 or NF-κB [21–24]. MeCP2 together with MBD1/2/3/4 comprise a family of nuclear proteins that is involved in regulation of DNA methylation [25, 26]. Previous studies by our and other labs have demonstrated a close association of MeCP2 with ERα promoter which is critical for ERα expression [26, 27]. PARP-1 plays an important role in the DNA repair pathway and its inhibitors have been explored as novel therapeutic agents for the treatment of hereditary breast cancers harboring mutations of BRCA1/2 [28]. Future studies will focus on how change of polyamine levels and/or the loss of ODC protein affect the DNA binding activity of the newly identified regulatory factors to the ERα promoter region.

DFMO has demonstrated considerable promise in clinical chemoprevention trials validating the polyamine pathway as an important clinical target [29, 30]. Unfortunately, the encouraging preclinical results did not translate well into the clinical setting when DFMO was tested as a chemotherapeutic agent [31]. This is probably due to low efficiency of drug transport, rapid turnover of the target, and compensatory increase in the uptake of polyamines from circulation [32]. Thus the continued search for more effective agents that interfere with polyamine metabolism is necessary. We observed in this study that treatment with exogenous spermine or overexpression of AZI failed to rescue the growth inhibition by ODC KD suggesting that ODC–AZ may regulate cell proliferation through at least one other partner protein, which is functionally substituting for AZ. Identification of the precise mechanisms by which ODC is regulated would aid in development of more effective agents in targeting ODC in breast cancer treatment.

In summary, the results of these studies augment our understanding of the molecular mechanisms for phenotype-specific regulation of ERα by polyamine biosynthesis enzyme.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by NIH Grants CA 51085 and CA 98454, the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, Susan G. Komen Foundation and the Samuel and Emma Winters Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Qingsong Zhu, The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Johns, Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Lihua Jin, The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Johns, Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Robert A. Casero, The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, Johns, Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA

Nancy E. Davidson, Department of Pharmacology & Chemical Biology, University, of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, 5150 Centre Avenue, Suite 500, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA, davidsonne@upmc.edu.

Yi Huang, Department of Pharmacology & Chemical Biology, University, of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA; University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, 5150 Centre Avenue, Suite 500, Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA, davidsonne@upmc.edu; Email: yih26@pitt.edu.

References

- 1.Porter CW, Herrera-Ornelas L, Pera P, Petrelli NF, Mittelman A. Polyamine biosynthetic activity in normal and neoplastic human colorectal tissues. Cancer. 1987;60(6):1275–1281. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870915)60:6<1275::aid-cncr2820600619>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.LaMuraglia GM, Lacaine F, Malt RA. High ornithine decarboxylase activity and polyamine levels in human colorectal neoplasia. Ann Surg. 1986;204(1):89–93. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198607000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manni A. Polyamine involvement in breast cancer phenotype. In Vivo. 2002;16(6):493–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manni A. The role of polyamines in the hormonal control of breast cancer cell proliferation. Cancer Treat Res. 1994;71:209–225. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-2592-9_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas T, Thomas TJ. Estradiol control of ornithine decarboxylase mRNA, enzyme activity, and polyamine levels in MCF-7 breast cancer cells: therapeutic implications. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1994;29(2):189–201. doi: 10.1007/BF00665680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen FJ, Manni A, Glikman P, Bartholomew M, Demers L. Involvement of the polyamine pathway in antiestrogen-induced growth inhibition of human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1988;48(23):6819–6825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nemoto T, Hori H, Yoshimoto M, Seyama Y, Kubota S. Overexpression of ornithine decarboxylase enhances endothelial proliferation by suppressing endostatin expression. Blood. 2002;99(4):1478–1481. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.4.1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang Y, Hager ER, Phillips DL, Dunn VR, Hacker A, Frydman B, Kink JA, Valasinas AL, Reddy VK, Marton LJ, et al. A novel polyamine analog inhibits growth and induces apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(7):2769–2777. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang Y, Keen JC, Pledgie A, Marton LJ, Zhu T, Sukumar S, Park BH, Blair B, Brenner K, Casero RA, Jr., et al. Polyamine analogues down-regulate estrogen receptor alpha expression in human breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(28):19055–19063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600910200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergeron RJ, Neims AH, McManis JS, Hawthorne TR, Vinson JR, Bortell R, Ingeno MJ. Synthetic polyamine analogues as antineoplastics. J Med Chem. 1988;31(6):1183–1190. doi: 10.1021/jm00401a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seely JE, Pegg AE. Ornithine decarboxylase (mouse kidney) Methods Enzymol. 1983;94:158–161. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(83)94025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, Devereux W, Woster PM, Stewart TM, Hacker A, Casero RA., Jr. Cloning and characterization of a human polyamine oxidase that is inducible by polyamine analogue exposure. Cancer Res. 2001;61(14):5370–5373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang Y, Stewart TM, Wu Y, Baylin SB, Marton LJ, Perkins B, Jones RJ, Woster PM, Casero RA., Jr. Novel oligoamine analogues inhibit lysine-specific demethylase 1 and induce reexpression of epigenetically silenced genes. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(23):7217–7228. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell JL, Leyser A, Holtorff MS, Bates JS, Frydman B, Valasinas AL, Reddy VK, Marton LJ. Antizyme induction by polyamine analogues as a factor of cell growth inhibition. Biochem J. 2002;366(Pt 2):663–671. doi: 10.1042/BJ20011612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell JL, Simkus CL, Thane TK, Tokarz P, Bonar MM, Frydman B, Valasinas AL, Reddy VK, Marton LJ. Antizyme induction mediates feedback limitation of the incorporation of specific polyamine analogues in tissue culture. Biochem J. 2004;384(Pt 2):271–279. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murai N, Murakami Y, Matsufuji S. Identification of nuclear export signals in antizyme-1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(45):44791–44798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newman RM, Mobascher A, Mangold U, Koike C, Diah S, Schmidt M, Finley D, Zetter BR. Antizyme targets cyclin D1 for degradation. A novel mechanism for cell growth repression. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(40):41504–41511. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407349200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang Y, Keen JC, Hager E, Smith R, Hacker A, Frydman B, Valasinas AL, Reddy VK, Marton LJ, Casero RA, Jr., et al. Regulation of polyamine analogue cytotoxicity by c-Jun in human MDA-MB-435 cancer cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2004;2(2):81–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang Y, Pledgie A, Rubin E, Marton LJ, Woster PM, Sukumar S, Casero RA, Jr., Davidson NE. Role of p53/p21(Waf1/ Cip1) in the regulation of polyamine analogue-induced growth inhibition and cell death in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4(9):1006–1013. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.9.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang Y, Pledgie A, Casero R, Jr., Davidson N. Molecular mechanisms of polyamine analogs in cancer cells. Anticancer Drugs. 2005;16(3):229–241. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200503000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zu X, Yu L, Sun Q, Liu F, Wang J, Xie Z, Wang Y, Xu W, Jiang Y. SP1 enhances Zbtb7A gene expression via direct binding to GC box in HePG2 cells. BMC Res Notes. 2009;2:175. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi WI, Jeon BN, Park H, Yoo JY, KimY S, Koh DI, Kim MH, Kim YR, Lee CE, Kim KS, et al. Proto-oncogene FBI-1 (Pokemon) and SREBP-1 synergistically activate transcription of fatty-acid synthase gene (FASN) J Biol Chem. 2008;283(43):29341–29354. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802477200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee DK, Kang JE, Park HJ, Kim MH, Yim TH, Kim JM, Heo MK, Kim KY, Kwon HJ, Hur MW. FBI-1 enhances transcription of the nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-kappaB)-responsive E-selectin gene by nuclear localization of the p65 subunit of NF-kappaB. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(30):27783–27791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504909200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qu H, Qu D, Chen F, Zhang Z, Liu B, Liu H. ZBTB7 overexpression contributes to malignancy in breast cancer. Cancer Invest. 2010;28(6):672–678. doi: 10.3109/07357901003631007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson ME, Westberry JM. Regulation of oestrogen receptor gene expression: new insights and novel mechanisms. J Neuroendocrinol. 2009;21(4):238–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2009.01830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Westberry JM, Trout AL, Wilson ME. Epigenetic regulation of estrogen receptor alpha gene expression in the mouse cortex during early postnatal development. Endocrinology. 2009;151(2):731–740. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharma D, Blum J, Yang X, Beaulieu N, Macleod AR, Davidson NE. Release of methyl CpG binding proteins and histone deacetylase 1 from the estrogen receptor alpha (ER) promoter upon reactivation in ER-negative human breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19(7):1740–1751. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frizzell KM, Kraus WL. PARP inhibitors and the treatment of breast cancer: beyond BRCA1/2? Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11(6):111. doi: 10.1186/bcr2451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Babbar N, Gerner EW. Targeting polyamines and inflammation for cancer prevention. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2011;188:49–64. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-10858-7_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mamont PS, Duchesne MC, Grove J, Bey P. Anti-proliferative properties of DL-alpha-difluoromethyl ornithine in cultured cells. A consequence of the irreversible inhibition of ornithine decarboxylase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1978;81(1):58–66. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(78)91630-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abeloff MD, Rosen ST, Luk GD, Baylin SB, Zeltzman M, Sjoerdsma A. Phase II trials of alpha-difluor-omethylornithine, an inhibitor of polyamine synthesis, in advanced small cell lung cancer and colon cancer. Cancer Treat Rep. 1986;70(7):843–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alhonen-Hongisto L, Poso H, Janne J. Inhibition by derivatives of diguanidines of cell proliferation in Ehrlich ascites cells grown in cultures. Biochem J. 1980;188(2):491–501. doi: 10.1042/bj1880491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]