Abstract

BACKGROUND

The effectiveness of school-based tobacco use prevention programs depends on proper implementation. This study examined factors associated with teachers’ implementation of a smoking prevention curriculum in a cluster randomized trial called Project SPLASH (Smoking Prevention Launch Among Students in Hawaii).

METHODS

A process evaluation was conducted and a cross-condition comparison used to examine whether teacher characteristics, teacher training, external facilitators and barriers, teacher attitudes, and curriculum attributes were associated with the dose of teacher implementation in the intervention and control arms of the study. Data were collected from a total of 62 middle school teachers in 20 public schools in Hawaii, during the 2000-2001 and 2001-2002 school years. Sources included teacher questionnaires and interviews. Chi-square test and t test revealed that implementation dose was related to teachers’ disciplinary backgrounds and skills and student enjoyment of the curriculum.

RESULTS

Content analysis, within case, and cross-case analyses of qualitative data revealed that implementing the curriculum in a yearlong class schedule and high teacher self-efficacy supported implementation, while high perceived curriculum complexity was associated with less complete implementation.

CONCLUSIONS

The results have implications for research, school health promotion practice, and the implementation of evidence-based youth tobacco use prevention curricula.

Keywords: smoking and tobacco, school health instruction, teaching techniques

Tobacco use prevention education beginning in middle school or earlier is critical for delaying the onset and decreasing the incidence of youth smoking, and for preventing smoking into adulthood.1,2 Studying factors related to the implementation of school health programs, including smoking prevention, are important because difficulties in the implementation process are common.3-6 Studies have found that in real-world settings, teachers do not always implement tobacco use and substance abuse prevention lessons according to specified guidelines. Hallfors and Godette found that only 19% of school district coordinators implemented evidence-based curricula with fidelity.7 Similarly, the School-Based Substance Use Prevention Program Study found that only 15% of teachers followed substance abuse prevention curricula guides very closely.8

Evidence-based youth tobacco use and substance abuse prevention programs use specific content, teaching strategies, and dosage to effectively influence and sustain changes in anti-use knowledge, attitudes, and behavior. Effective programs have reduced students’ use of tobacco and other substances from 20% to 75%,9,10 with some sustaining changes in antismoking knowledge, attitudes, and behavior for up to 6 years after the end of the program.9,11,12 Content for effective youth smoking prevention programs may include resistance skills training9,10,12,13 and social influences.9,13,14 When programs use effective teaching strategies that involve direct peer interaction, their effects have been shown to be stronger than programs using only effective content.9,10,15 Evidence-based smoking and substance abuse prevention programs also involve an average intensity of 16 hours of programming9,16 and are interactive.16

Studies of the implementation of smoking prevention programs have identified several factors related to this process: teacher training, teacher characteristics, teacher attitudes, organizational factors, and curriculum attributes. Several studies have evaluated the relation of these factors to use, fidelity, and dose of curriculum implementation.15,17-28 However, until recently, factors related to implementing tobacco prevention programs have received less attention than factors related to a school's decision to adopt (ie, uptake, initiation, commitment, acceptance) these programs.4,5,15 Identifying strategies to successfully implement tobacco use prevention curricula contributes to an understanding of how such programs may be translated to the real-world setting.

The purpose of this study was to identify organizational and individual factors associated with teachers’ implementation of an innovative tobacco use prevention curriculum targeting youth in Hawaii. Two research questions guided the study:

To what extent did teachers implement the recommended dose of the intervention and control curricula?

What factors were associated with teachers’ implementation of the curriculum?

METHODS

Subjects

Implementation of Project SPLASH (Smoking Prevention Launch Among Students in Hawaii) and Towards No Tobacco Use (TNT) Hawaii was assessed for process evaluation. The study sample of 62 teachers was obtained from the schools participating in the larger randomized trial. The dose and reach of both programs were evaluated. Factors associated with teachers’ implementation of the programs were also identified.

Instruments

Quantitative and qualitative data were collected from teacher and student questionnaires, teacher interviews and training evaluation questionnaires, and the Project SPLASH database (Table 1). Depending on the variables, quantitative, qualitative, or both types of measures were obtained to minimize data collection burden on teachers. The teacher questionnaires and interviews were used to inform the independent and outcome variables. These instruments were reviewed by the research team and pilot tested with 3 teachers to establish their face and content validity. Tests of internal consistency for multi-item measures yielded high Cronbach's alphas of 0.74-1.00.

Table 1.

Data Collection Procedures

| Data Collection Procedures | Process Evaluation Purpose | When Collected | Sampling Procedure | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher questionnaire | Evaluate teacher characteristics, teacher attitudes, curriculum attributes, and teacher implementation | End of seventh-grade school year; end of eighth-grade school year | All teachers | 62 |

| Teacher interview | Evaluate teacher characteristics, teacher training, external facilitators and barriers, teacher attitudes, and teacher implementation | End of seventh-grade school year/beginning of eighth-grade school year; end of eighth-grade school year | All teachers | 62 |

| Teacher training evaluation questionnaire | Evaluate teacher training and teacher attitudes | Beginning of eighth-grade school year | All teachers | 30 |

| Student surveys | Evaluate reach | Beginning and end of eighth-grade school year | All students aggregated at level of teachers’ classes | 4884 |

| Student feedback interviews | Evaluate reach | End of eighth-grade school year | Subsample | 725 |

| Student homework | Triangulate with other data sources and exploratory research to evaluate student reach | End of eighth-grade school year | Subsample | Varied* |

| Project SPLASH database | Evaluate teacher characteristics and external facilitators and barriers | Ongoing, database maintained by the main study | All teachers | 62 |

Sample size depended on the type of homework evaluated ranging from n = 20 to 2678.

Four questionnaires were developed, 1 each for seventh-grade SPLASH and TNT teachers and eighth-grade SPLASH and TNT teachers, and all teachers were given questionnaires. Three constructs were evaluated through the teacher questionnaires. Teacher attitudes and curriculum attributes were measured by 4 items. Teacher characteristics were measured by 9 items on the seventh-grade SPLASH and eighth-grade TNT questionnaires, while 8 items on the seventh-grade TNT and 10 items on the eighth-grade SPLASH questionnaires were used to measure this construct.

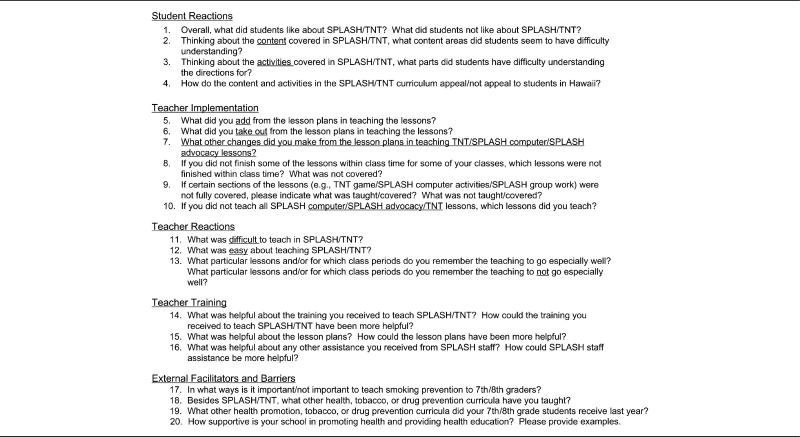

Teacher interviews were conducted to provide additional information not obtained from the teacher questionnaires. An interview guide with open-ended questions (24 and 28 for SPLASH across the 2 years, and 21 for TNT) guided the procedure. Most interviews were conducted in-person, while some were conducted by phone due to scheduling constraints. Selected questions from the interview guides are provided in Figure 1. (The complete interview guides are available on request from the first author.)

Figure 1.

Sample Teacher Interview Questions

Procedures

This study used process evaluation data from a randomized trial called Project SPLASH, which tested the effectiveness of a curriculum that emphasized student involvement on smoking rates in Hawaii middle school students, compared to a standard smoking prevention curriculum (Table 2). Project SPLASH, the experimental curriculum, comprised of 3 innovative components: computer lessons, a drama education program, and youth advocacy training.29 The control curriculum was based on Project TNT, an evidence-based, school-based smoking prevention program.30,31 This program was less interactive than the intervention program and primarily used social influences approaches.

Table 2.

Description of Project SPLASH and TNT Hawaii Curricula

| Grade | Lesson Number | Number of Days | Title and Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Project SPLASH: 45 minutes for each lesson | |||

| 7 | Computer 1 | 1 | Behavioral Aspects of Tobacco: Smoking rates and issues |

| 7 | Computer 2 | 1 | Immediate & Long-Term Health Consequences: Health, financial, and social consequences of tobacco use |

| 7 | Computer 3 | 1 | Quitting Smoking: Helping Your Family, Friends, & Yourself: Benefits of quitting smoking, how to quit, and how to help others quit |

| 7 | Drama 1-5 | 5 | Developing, Practicing, and Performing Anti-Tobacco Education Skits: Students work with drama educators to create anti-tobacco skits that are videotaped |

| 8 | Computer 4 | 1 | Uncovering the Truth About Tobacco Ads: How tobacco companies target youth through advertising and marketing |

| 8 | Computer 5 | 1 | Malama ka ‘Aina (Care of the Land): Impact of tobacco use on the environment |

| 8 | Advocacy 1 | 1 | Introduction to Youth Advocacy: Historical, national, and local advocates and how to become an advocate |

| 8 | Advocacy 2 | 1 | Media Literacy: Identifying how ads glamorize tobacco use and the truth behind those messages |

| 8 | Advocacy 3 | 2 | Policy Change & the Legislative Process: day 1—learning about the state legislative process and tobacco control laws; day 2—participate in a mock hearing led by the drama educators |

| 8 | Advocacy 4 | 1 | Advocating for a Change: Develop activities to voice opinions and motivate others |

| TNT Hawaii: 45 minutes for each lesson | |||

| 7 | 1 | 1 | Effective Listening & Tobacco Information: Importance of being active listeners |

| 7 | 2 | 1 | Tobacco History: History of tobacco |

| 7 | 3 | 1 | Course & Consequences of Tobacco Use: Stages of nicotine addiction and decision-making strategies |

| 7 | 4 | 1 | Self-Esteem: Practice techniques to improve self-esteem |

| 7 | 5 | 1 | Being True to Yourself & Changing Negative Thoughts (Peer Pressure): How to deal with peer pressure and changing thoughts about what may appear to be threatening situations |

| 7 | 6 | 1 | With a Little Help From Friends: Role play scenarios to say “no” to tobacco |

| 8 | 7 | 1 | Clearing the Smoke About Cigarettes: Conduct group research on current tobacco facts and information |

| 8 | 8 | 1 | Being Tobacco-Free: Addiction and how to convince others to quit smoking |

| 8 | 9 | 1 | Effective Communication: Discussion and role plays on communicating effectively |

| 8 | 10 | 1 | Assertiveness Training & Refusal Skills Practice: Discuss and practice ways to be assertive |

| 8 | 11 | 1 | Tobacco Advertising: Worksheets on replacement smokers, media, and tobacco companies |

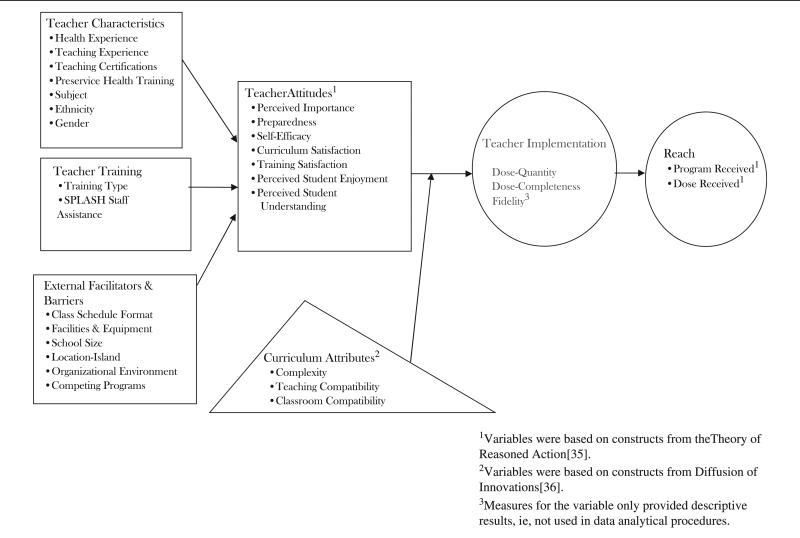

The process evaluation was based on a conceptual model with teacher implementation as the primary outcome (Figure 2). Factors proposed to influence teacher implementation were teacher characteristics, teacher training, external facilitators and barriers, teacher attitudes, and curriculum attributes.

Figure 2.

Process Evaluation Conceptual Model

According to the Theory of Reasoned Action, it was hypothesized that the influence of teacher characteristics, teacher training, and external facilitators and barriers was mediated by teacher attitudes. This theory indicates that a person's behavior is determined by factors related to knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about the behavior.32 Variables outlined in the conceptual model addressing teacher attitudes cover the knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs related to the behavior, that is, teacher implementation.

Curriculum attributes was a construct based on Diffusion of Innovations and was hypothesized to moderate the influence of teacher characteristics, teacher training, and external facilitators and barriers on teacher implementation. According to this theory, an innovation's compatibility (fit) and complexity (difficulty of use) are also attributes that affect the speed and extent of the diffusion process. Thus, teacher implementation was proposed to be moderated by the characteristics of the curriculum, that is, teaching compatibility, classroom compatibility, and complexity.33

The primary outcome variable was implementation dose, defined as the extent of intervention units delivered (as reported by teachers) and comprised of 2 components: quantity and completeness.34 A composite teacher implementation measure was created by computing the average of the percent lessons taught and finished within class time dichotomized into high, 66.7-100%, and low, that is, 0-66.6%, of lessons implemented for SPLASH and TNT (Table 3). Other outcome variables such as reach and fidelity of teacher implementation provided additional descriptive results.

Table 3.

Dose Items and Measures

| Variable | Measure | Variable Type | Program/Grade | Questionnaire Items | Response Format/Coding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity: lessons taught | % Lessons taught | Dichotomous: high/low | SPLASH seventh | Indicate the number of SPLASH computer classes you taught | No. classes taught |

| SPLASH eighth | For the computer lessons, indicate whether you taught both lessons | 0 = no, 1 = yes | |||

| Indicate the number of youth advocacy lessons you taught | No. lessons taught | ||||

| TNT seventh | Indicate the number of TNT classes you taught | No. classes taught | |||

| TNT eighth | Indicate the number of TNT lessons you taught | No. lessons taught | |||

| Completeness: lessons finished | % Lessons finished | Dichotomous: high/low | SPLASH seventh | Indicate the number of classes that were not finished within class time | No. classes not finished |

| SPLASH eighth | Indicate the number of lessons that were not finished within class time | No. lessons not finished | |||

| TNT seventh | Indicate the number of classes that were not finished within class time | No. classes not finished | |||

| TNT eighth | Indicate the number of lessons that were not finished within class time | No. lessons not finished |

Independent variables were teacher characteristics, teacher training, external facilitators and barriers, teacher attitudes, and curriculum attributes. Quantitative measures for teacher characteristics, teacher training, and external facilitators and barriers were operationalized as categorical or dichotomous variables, while measures for teacher attitudes and curriculum attributes used ordinal scales. Variance, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis, and normality were examined for each variable. Upon data screening, necessary transformations were conducted on selected variables.

Data Analysis

A cross-condition comparison was used to identify facilitators and barriers that influenced self-reported teacher implementation, that is, dose of the curricula, from the process evaluation results. Bivariate and multivariate analytical procedures were used. Quantitative analysis involved chi-square test, Fisher's exact test, and t test to determine if characteristics differed significantly between the SPLASH and the TNT teachers and to determine significant associations between the dependent and the independent variables. Logistic regression was used to determine the independent contributions of each variable. Variables selected for the logistic regression were those that showed significant results in bivariate analyses.

Qualitative analysis involved content analysis. The variables identified in this study served as general coding categories to initially guide the analysis. For example “teacher training” “SPLASH staff assistance” would be a general code. The constant comparative method was used to obtain more specific codes. Specific codes for “SPLASH staff assistance” would include “questions,” “materials,” and “visits.” A codebook was maintained, and NUDISTVivo was used to manage and analyze the qualitative data. Descriptive results were displayed using matrices based on the codes identified from the coding process. These matrices served to further summarize results and examine patterns of responses. Findings obtained from the different data sources were triangulated to determine convergence of results.

RESULTS

Response Rates

A total of 60 teachers completed either a questionnaire or an interview, with 39 (63%) completing both. The average response rate for the teacher questionnaires from both programs and grades was 86.2%. The average response rate for the teacher interviews from both programs and grades was 81.3%. Respondents were from seventh (n = 27) and eighth (n = 25) grades, and from the SPLASH (n = 34) and TNT (n = 18) study arms.

Implementation Dose

Results on teacher-reported implementation dose were analyzed to address the first research question: “To what extent did teachers implement the recommended dose of the intervention and control curricula?” Of the 56 teachers who responded to questionnaires (the source of quantitative measures on dose), 53 answered the items used to compute teacher-reported dose. Results indicated that most teachers in both programs implemented most of their lessons, with 71.4% of SPLASH and 72.2% of TNT teachers reporting high implementation of their curriculum.

Factors Associated With Implementation

Results from bivariate analyses identified variables that were significantly associated with the primary outcome variable, teacher-reported implementation dose, to answer the second research question: What factors are associated with teachers’ implementation of the curriculum? Measures of the independent variables for the bivariate analyses were combined for the 2 programs because program type was not significantly associated with implementation levels.

The level of significance to determine associations between the independent variables and teacher-reported dose was set at p ≤ .10 because of the small sample size. Sample size influences need to be taken into account when setting a significance level.35 A nonsignificant result may be more likely if the number of observations is small, even if there is a large real effect.36

Bivariate analyses revealed that teacher characteristics were significantly associated with teacher-reported dose (Table 4). Being physical education certified, pursuing the Hawaii state health teacher endorsement—a newly implemented state health education certification—receiving preservice health training, and using the Internet daily outside SPLASH were significantly associated with low implementation dose. Teachers pursuing the Hawaii state health teacher endorsement were more likely to have taken health courses (37.5%, p = .024) than those who were not pursuing the health endorsement, yet were associated with a lower implementation rate of lessons.

Table 4.

Independent Variables Significantly Associated With Implementation Dose

| Low (0-66.6%) |

High (66.7-100%) |

Chi-Square/Fisher's Exact Test |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | n | Frequency | % | n | Frequency | % | Value | df | p |

| Teaching experience* | |||||||||

| Physical education certified | 15 | 9 | 60.0 | 38 | 11 | 28.9 | 4.14 | 1 | .036 |

| Purse Hawaii health endorsement | 15 | 8 | 53.3 | 38 | 3 | 7.9 | 13.50 | 1 | .001 |

| Taken health courses† | 7 | 4 | 57.1 | 15 | 2 | 13.3 | 4.62 | 1 | .054 |

| Internet experience (SPLASH only) | 10 | 24 | 2.84 | 1 | .098 | ||||

| Never-once/week | 4 | 40.0 | 17 | 70.8 | |||||

| Daily | 6 | 60.0 | 7 | 38.2 | |||||

Responses were “yes/no” for each category of teaching experience, that is, 5 dichotomous variables.

Results reflect eighth-grade teachers.

Logistic regression results revealed very large confidence intervals. Since this multivariate analysis was unstable for meaningful interpretation, results were not used to identify factors influencing teacher-reported implementation.

An examination of the qualitative data revealed additional factors that may be related to teacher implementation. In both programs, proportionally more teachers who taught in yearlong class schedule formats and those who indicated having high self-efficacy fully implemented their lessons. In both programs, more teachers who indicated that their curriculum was complex only partially implemented their lessons. These results suggest that in addition to the factors identified from the bivariate analysis, factors obtained from the qualitative results may be associated with teacher implementation.

DISCUSSION

Teachers’ Background, Attitudes, and Skills

Results revealing that teachers who were pursuing the Hawaii state health teacher endorsement were more likely to have taken health courses than those who were not pursuing the certification but implemented less lessons than those who were not pursing a certification were unexpected. Teachers explained these results by noting that because they had to comply with the state health teaching standards to obtain their endorsement, they only implemented lessons that addressed those standards.

Findings that prior health course work and physical education certification were inversely associated with implementation are consistent with results suggesting that the degree of implementation may be related to whether teachers have specifically taught smoking and substance abuse prevention curricula. Previous experience and/or familiarity teaching the content and using the educational strategies recommended for smoking and substance abuse prevention curricula, but not general familiarity with health topics, may determine the extent that teachers implement new curricula. In essence, relevant and more specific professional training, rather than taking course work in general, may positively influence the implementation of lessons.

Qualitative findings support the conclusion that teachers who were not formally trained in health education may not have had sufficient training on effective health education pedagogy to prevent students’ tobacco use. The issues teachers discussed relating to low self-efficacy suggested that those who may not have training in health education may not be familiar with novel teaching strategies found in smoking prevention education. A SPLASH teacher explained, “I left out the self-esteem part at the beginning because I couldn't make the connection between the two [smoking and self-esteem].”

Daily Internet usage was also significantly associated with low implementation dose, another counterintuitive finding. Examining classroom teachers’ computer experience in relation to health education has not been previously studied. Further exploration regarding teachers’ computer experience in relation to technology-based smoking prevention curricula is needed since technology-based health education continues to be developed.

Teacher Training

Previous studies found that having received training on a smoking prevention or health education curriculum was associated with implementation dose.6,19,25,37 This study evaluated type of training, and not whether training was received, to investigate whether training type was related to self-reported implementation dose. Workshop, individual, or no training was analyzed in relation to implementation dose, and none of these training types was found to be associated with dose.

The different delivery formats used to train teachers on implementing SPLASH and TNT may not have been distinct enough to influence implementation dose, despite previous findings that in-service training is strongly associated with dose. These studies found that “extensive”38 training strategies to teach a curriculum, for example, developing an implementation plan37 or practicing teaching methods,6 may be critical in influencing teachers’ implementation of the curriculum. Indeed, many teachers who attended workshops or received individual trainings to teach SPLASH or TNT commented that they did not find their training helpful because it did not provide additional assistance than if they reviewed the curriculum on their own.

Class Schedule Format and Curriculum Attributes

Factors external to teachers, for example, time limitations, were also found to be associated with implementation. The qualitative results on class schedule format and implementation levels suggested that a shorter class period duration or school term, that is, semester or quarter, instead of yearlong was a time barrier toward full curriculum implementation. A SPLASH teacher explained, “. . . but also it was time . . . because I only have these kids for a semester. If health was a year course, I probably could've finished it more completely.”

Curriculum complexity and scheduling difficulties were other factors that may have impeded implementation of both programs. A SPLASH teacher described implementation difficulties as follows:

I like the plan of this, but there's so many things that have to be coordinated. You gotta get the survey coordinated. Then you gotta get the computer lab time where they're open. Then you gotta coordinate it with when Bill's [drama artist, not actual name] going to be free or somebody else is going to be free to lead them [students], and then when somebody can tape it. It all has to be pretty much drop anything else you're doing and stick this in there.

TNT teachers also thought that the lesson plans and instructions to carry out activities were complex.

The only thing that was difficult was that it was really long. Six lessons was not six days.

Study Strengths and Limitations

This study compared the extent to which the content and teaching strategies of 2 programs were implemented. Evaluating the implementation of a smoking prevention program in relation to both study conditions revealed what teachers tend to “naturally” implement, regardless of their lesson plans, and also helped explain study outcomes.

The qualitative results provided insight into the implementation of smoking prevention curricula and how particular factors may influence implementation. This study's internal validity and reliability were also strengthened through the use of multiple data sources and analytic techniques that indicated an overall convergence of findings across data sources.

This study also revealed additional factors, such as teaching background and professional skills, related to teacher implementation of smoking prevention curricula not found in previous studies. Findings from this study may provide additional criteria for quality teacher implementation of evidence-based smoking prevention and substance abuse prevention programs.

The methods to ensure the development of valid and reliable measures of the process evaluation outcomes, especially fidelity, should be given critical focus in future process evaluation studies. The extent to which teachers maintained fidelity in teaching their curricula was not evaluated in this study. Defining “fidelity,” or what constitutes quality of delivery and how to measure this concept, has been challenging in process evaluations.4,34 When operationalizing process measures, careful attention should be given to assure that the highest possible degree of validity and reliability is obtained for such measures.

The study's lack of power (n = 60) limited the use of the multivariate analysis. Only results from the bivariate analysis between the independent variables and the implementation dose were used, limiting this study's ability to identify directionality and to control for confounding variables.

Conclusions—Implications for Research and Practice

Smoking prevention curricula need to be developed with practical considerations of teachers’ time limitations to teach such programs, given their teaching expertise, curriculum requirements, and length of school terms. Class schedule format needs to be considered keeping in mind that teachers on a yearlong class schedule would be more likely to completely implement lessons. Effective smoking and substance abuse prevention curricula require a specific “dose” involving number and duration of lessons to be effective.16 Additionally, schools may also offer health as a yearlong subject to allow more health promotion topics to be fully implemented.

Schools should play a role in supporting teachers’ implementation of smoking prevention programs by ensuring that teachers have the appropriate background. Schools in Hawaii should be aware that smoking prevention education in their schools may not be fully implemented since most health teachers in Hawaii were found to have a physical education background and not health certification. Curriculum complexity was also found to relate to partial implementation. Because effective smoking and substance abuse curricula employ interactive strategies, they are often considered complex and are therefore less likely to be implemented.18,23,27

The finding that teachers with high self-efficacy were more likely to fully implement their curriculum confirms the importance of increasing teachers’ confidence in their ability to fully implement a smoking prevention curriculum. If teachers do not have the appropriate background to proficiently implement smoking prevention curricula, schools should support teacher in-service training to implement such programs by allowing paid time off to receive adequate training. Training that involves informing teachers of the critical strategies of an evidence-based curriculum and increasing their ability to implement such strategies, as found in previous studies, may encourage teachers to more likely implement those innovative, yet complex components.20,25,39

Further research on the extent teachers need to adhere to smoking prevention curricula guidelines without compromising their effectiveness should be conducted. From a research standpoint, adherence to curriculum protocols is key to achieving the intended effects of effective smoking prevention curricula. In practice, when teachers modify curricula, they may be attempting to address local, cultural, teaching, and/or student needs. If the critical elements of a curriculum are identified, teacher modifications may be encouraged as long as the key elements of the program are delivered.

Program developers should systematically consult with the teachers in their research to develop and identify effective smoking and substance abuse prevention and other health promotion curricula. Issues that exist in the school setting are sometimes in conflict with the critical elements of smoking prevention programs. For example, effective tobacco use prevention curricula require a particular dose of lessons, and their full implementation may be more feasible within longer school terms. Additionally, although interactive teaching strategies are a key feature of effective smoking and substance abuse prevention curricula, this study indicated that such aspects were barriers during implementation since teachers considered those strategies complex.

Participatory approaches in health promotion research to develop interventions may help address the challenging aspects of program implementation. Program developers may obtain feedback on teachers’ implementation needs and the feasibility of implementing a curriculum in their school setting. Program implementers, as key “agents of change,” should be involved in the stages of research to develop an intervention protocol. Such an approach ensures better implementation in and translation to the practice setting. Finally, by including the populations being served in research and program planning, the unique needs of diverse settings and communities are respected, which is key in conducting health promotion research and delivering interventions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute, grant #CA77108, and by supplemental funding from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. We thank Allan Steckler, DrPH; Deborah Rohm Young, PhD; Laura Linnan, ScD; and Kurt Ribisl, PhD, for guidance with this study. We also thank the Project SPLASH staff, who assisted in the data collection, at the Cancer Research Center of Hawaii: Karin Koga, MPH; Janice Nako-Piburn, MA; and Kevin Lunde and Alana Steffen, PhD, for assistance with data analysis.

Footnotes

Citation: Sy A, Glanz K. Factors influencing teachers’ implementation of an innovative tobacco prevention curriculum for multiethnic youth: Project SPLASH. J Sch Health. 2008; 78: 264-273.

REFERENCES

- 1.Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ, Pierce JP. Determining the probability of future smoking among adolescents. Addiction. 2001;96(2):313–323. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96231315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Health and Human Services . Healthy People 2010. US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Basch CE. Research on disseminating and implementing health education programs in schools. J Sch Health. 1984;54(6):57–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dusenbury L, Brannigan R, Falco M, Hansen WB. A review of research on fidelity of implementation: implications for drug abuse prevention in school settings. Health Educ Res. 2003;18(2):237–256. doi: 10.1093/her/18.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCormick LK, Steckler AB, McLeroy KR. Diffusion of innovations in schools: a study of adoption and implementation of school-based tobacco prevention curricula. Am J Health Promot. 1995;9(3):210–219. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-9.3.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rohrbach LA, Graham JW, Hansen WB. Diffusion of a school-based substance abuse prevention program: predictors of program implementation. Prev Med. 1993;22(2):237–260. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1993.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hallfors D, Godette D. Will the ‘Principles of Effectiveness’ improve prevention practice? Early findings from a diffusion study. Health Educ Res. 2002;17(4):461–470. doi: 10.1093/her/17.4.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ringwalt CL, Ennett S, Johnson R, et al. Factors associated with fidelity to substance use prevention curriculum guides in the nation's middle schools. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30(3):375–391. doi: 10.1177/1090198103030003010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Center for Substance Abuse Prevention [February 1, 2006];CSAP's model programs. Available at: http://www.modelprograms.samhsa.gov/template.cfm?CFID=3619855&CFTOKEN=52400931.

- 10.Perry CL, Williams CL, Komro KA, et al. Project Northland high school interventions: community action to reduce adolescent alcohol use. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27(1):29–49. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Botvin GJ, Griffin KW, Diaz T, Scheier LM, Williams C, Epstein JA. Preventing illicit drug use in adolescents: long-term follow-up data from a randomized control trial of a school population. Addict Behav. 2000;25(5):769–774. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dusenbury L, Falco M, Lake A. A review of the evaluation of 47 drug abuse prevention curricula available nationally. J Sch Health. 1997;67(4):127–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1997.tb03431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tobler NS. Meta-analysis of Adolescent Drug Prevention Programs: results of the 1993 meta-analysis. In: Bukoski WJ, editor. Meta-Analysis of Drug Abuse Prevention Programs. NIDA Research Monograph 170, NIH Publication 97-4146. National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse; Rockville, MD: 1997. pp. 97–4146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Effectiveness of school-based programs as a component of a statewide tobacco control initiative—Oregon, 1999-2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50(31):663–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ennett ST, Ringwalt CL, Thorne J, et al. A comparison of current practice in school-based substance use prevention programs with meta-analysis findings. Prev Sci. 2003;4(1):1–14. doi: 10.1023/a:1021777109369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tobler NS, Roona MR, Oschsborn P, Marshall DG, Streke AV, Stackpole KM. School-based adolescent drug prevention programs: 1998 meta-analysis. J Prim Prev. 2000;20(4):275–336. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hausman AJ, Ruzek SB. Implementation of comprehensive school health education in elementary schools: focus on teacher concerns. J Sch Health. 1995;65(3):81–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1995.tb03352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helitzer D, Yoon SJ, Wallerstein N, Dow y Garcia-Velarde L. The role of process evaluation in the training of facilitators for an adolescent health education program. J Sch Health. 2000;70(4):141–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2000.tb06460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson CC, Li D, Galati T, Pedersen S, Smyth M, Parcel GS. Maintenance of the classroom health education curricula: results from the CATCH-ON study. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30(4):476–488. doi: 10.1177/1090198103253610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kealey KA, Peterson AV, Jr, Gaul MA, Dinh KT. Teacher training as a behavior change process: principles and results from a longitudinal study. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27(1):64–81. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelder SH, Mitchell PD, McKenzie TL, et al. Long-term implementation of the CATCH physical education program. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30(4):463–475. doi: 10.1177/1090198103253538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levenson-Gingiss P, Hamilton R. Determinants of teachers’ plans to continue teaching a sexuality education course. Fam Community Health. 1989;12:40–53. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lytle LA, Ward J, Nader PR, Pedersen S, Williston BJ. Maintenance of a health promotion program in elementary schools: results from the CATCH-ON study key informant interviews. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30(4):503–518. doi: 10.1177/1090198103253655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parcel GS, Perry CL, Kelder SH, et al. School climate and the institutionalization of the CATCH program. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30(4):489–502. doi: 10.1177/1090198103253650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perry-Casler SM, Price JH, Telljohann SK, Chesney BK. National assessment of early elementary teachers perceived self-efficacy for teaching tobacco prevention based on the CDC guidelines. J Sch Health. 1997;67(8):348–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1997.tb03471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romano JL. School personnel training for the prevention of tobacco, alcohol, and other drug use: issues and outcomes. J Drug Educ. 1997;27(3):245–258. doi: 10.2190/HYEW-1EEJ-74PD-P1E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith DW, Steckler AB, McCormick LK, McElroy KR. Lessons learned about disseminating health curricula to schools. J Sch Health. 1995;26(1):37–43. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tappe MK, Galer-Unit RA, Bailey KC. Long-term implementation of the teenage health teaching modules by trained teachers: a case study. J Sch Health. 1995;65(10):411–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1995.tb08203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glanz K, Lunde KB, Leakey TA, et al. Activating multiethnic youth for smoking prevention: Design and baseline findings from Project SPLASH. J Cancer Educ. 2007;22(1):56–61. doi: 10.1007/BF03174377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sussman S, Dent CW, Stacy AW, Hodgson CS, Burton D, Flay BR. Project Towards No Tobacco Use: implementation, process and post-test knowledge evaluation. Health Educ Res. 1993;8(1):109–123. doi: 10.1093/her/8.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sussman S, Dent CW, Stacy AW, Hodgson CS, Burton D, Flay BR. Project Towards No Tobacco Use: 1-year behavior outcomes. Am J Public Health. 1993;83(9):1245–1250. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.9.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Azjen I, Fishbein M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. Prentice-Hall; Englewood Cliffs, NJ: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogers E. Diffusion of Innovations. 4th ed. Free Press; New York, NY: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steckler A, Linnan L. Process Evaluation for Public Health Interventions and Research. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, Calif: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson B. The concept of statistical significance testing. Meas Update. 1994;4(1):5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Altman D, Gore SM, Gardner MJ, Pocock SJ. Statistical guidelines for contributors to medical journals. In: Altman D, Machin D, Bryant TN, Gardner MJ, editors. Statistics With Confidence: Confidence Intervals and Statistical Guidelines. 2nd ed. BMJ Books; London, England: 2000. pp. 171–190. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parcel G, Ross JG, Lavin AT, Portnoy B, Nelson GD, Winters F. Enhancing implementation of the Teenage Health Teaching Modules. J Sch Health. 1991;61(1):35–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1991.tb07857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perry C, Murray DM, Griffin G. Evaluating the statewide dissemination of smoking prevention curricula: factors in teacher compliance. J Sch Health. 1990;60(10):501–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1990.tb05890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Markham CM, Basen-Engquist K, Coyle KK, Addy RC, Parcel GS. Safer choices, a school-based HIV, STD, and pregnancy prevention program for adolescents: process evaluation issues related to curriculum implementation. In: Steckler AL, Linnan L, editors. Process Evaluation for Public Health Interventions and Research. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, Calif: 2002. pp. 209–248. [Google Scholar]