Future wearable electronics, displays and photovoltaic devices require materials which are mechanically flexible, lightweight and low-cost, in addition to being electrically conductive and optically transparent.1–3 Nowadays indium tin oxide (ITO) is the most wide spread transparent conductor in optoelectronic applications, however the mechanical rigidity of this material limits its use for future flexible devices. In the race to find novel transparent conductors, graphene monolayers and multilayers are the leading candidates as they have the potential to satisfy all future requirements. Graphene, one-atom-thick layer of carbon atoms, is transparent,4 conducting,5, 6 bendable7 and yet one of the strongest known materials.8 However, the use of graphene as a truly transparent conductor remains a great challenge because the lowest values of its sheet resistance (Rs) demonstrated so far are above the values of commercially available ITO (i.e. 10 Ω/□ at an optical transmittance Tr = 85%9). Currently many efforts are concentrated on decreasing the Rs of graphene-based materials while maintaining a high Tr, which will allow their potential to be harnessed in optoelectronic applications. To date, the best values of sheet resistance and transmittance found in graphene-based materials are still far from the performances of ITO, with typical values of Rs = 30 Ω/□ at Tr = 90% for graphene multilayers7, 12 and Rs = 125 Ω/□ at Tr = 97.7% for chemically doped graphene.7, 10, 11

Here we report novel graphene-based transparent conductors with a sheet resistance of 8.8 Ω/□ at Tr = 84%, a carrier density as high as 8.9 × 1014cm−2 and a room temperature carrier mean free path as large as ∼0.6 μm. These materials are obtained by intercalating few-layer graphene (FLG) with ferric chloride (FeCl3).13, 14 Through a combined study of electrical transport and optical transmission measurements we demonstrate that FeCl3 enhances the electrical conductivity of FLG while leaving these graphene-based materials highly transparent. We also show that FeCl3-FLGs are stable in air up to one year, which demonstrates the potential of these materials for industrial production of transparent conductors. The unique combination of record low sheet resistance, high optical transparency and macroscopic room temperature mean free path has not been demonstrated so far in any other doped graphene system, and opens new avenues for graphene-based optoelectronics.

Pristine FLG ranging from two- to five-layers (2L to 5L) were obtained by micromechanical cleavage of natural graphite5 on glass or SiO2/Si. The number of layers composing each FLG was determined by optical contrast and Raman spectroscopy (see Supporting Information). The intercalation process with FeCl3 was performed in vacuum with the two-zone vapor transport method.15 FeCl3 is sublimated in the lowest temperature zone and it diffuses to the higher temperature zone where the intercalation of FLG takes place (see Experimental Section). The structural, electrical and optical characterization is carried out by means of three complementary experimental techniques: low-temperature charge transport, optical transmission and Raman spectroscopy.

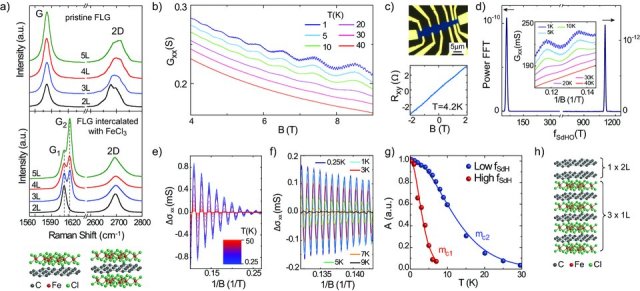

Figure 1a shows the Raman spectra of pristine FLG on SiO2/Si, with the G-band at 1580 cm−1 and the 2D-band at 2700 cm−1.16, 17 As expected for pristine FLGs, increasing the number of layers results in an increase of the G-band intensity,18 whereas the 2D-band acquires a multi-peak structure.16, 17 The charge transfer from FeCl3 to graphene modifies the Raman spectra of FLGs in two distinctive ways:13, 14, 19 an upshift of the G-band and a change of the 2D-band from multi- to single-peak structure, respectively (see Figure 1a). The shift of the G-band to G1 = 1612 cm−1 is a signature of a graphene sheet with only one adjacent FeCl3 layer, whereas the shift to G2 = 1625 cm−1 characterizes a graphene sheet sandwiched between two FeCl3 layers [13–15] (see Figure 1a). The frequencies, linewidths and lineshapes of the G1 and G2 peaks do not depend on the number of graphene layers which indicates the decoupling of the FLGs into separate monolayers due to the intercalation of FeCl3 between the graphene sheets. This is consistent with the changes in the 2D-band shape and with the Raman studies of other intercalants such as Potassium20, 21 and Rubidium.21 These observations allow us to identify the structure of intercalated 2L samples as one FeCl3 layer sandwiched between the two graphene sheets. However, the structural determination of thicker FeCl3-FLG cannot rely uniquely on the Raman spectra, it requires complementary knowledge from electrical transport experiments. Direct structural determination for example by X-ray diffraction would be valuable to confirm the findings of Raman and electrical transport measurements, however the small thickness of FeCl3-FLG and the substrate effects make it difficult to apply such technique to these systems.

Figure 1.

a) The G and 2D Raman bands of pristine FLG (top) and of FeCl3-FLG (bottom) with different thicknesses ranging from 2L to 5L. The Raman shift of G to G1 and G2 stem for a graphene sheet with one or two adjacent FeCl3 layers as shown by the schematic crystal structure. b) Longitudinal conductance (Gxx) as a function of magnetic field at different temperatures (curves shifted for clarity). c) Top panel: false color optical microscope image of an intercalated Hall bar device. Bottom panel: Hall resistance (Rxy) as function of magnetic field. d) Fourier transform of Gxx(1/B) with peaks at frequencies fSdHO1 = 1100T and fSdHO2 = 55T. The inset shows Gxx as a function of inverse magnetic field at different temperatures (curves shifted for clarity). Panels e) and f), respectively, show the low- and high- frequency magneto-conductivity oscillations vs 1/B extracted from the measurements in b) (see Experimental section). g) Temperature decay of the amplitude (A) of Δσxx oscillations at B = 6.2T. The amplitudes are normalized to their values at T = 0.25K. The continuous lines are fits to A(T)/A(0.25) with the cyclotron mass mc as the only fitting parameter. h) Schematic crystal structure of a 5L FeCl3-FLG in which electrical transport takes place through four parallel conductive planes, one with bilayer character and three with monolayer character.

To characterize the structure of thicker FeCl3-FLG, we study the oscillatory behaviour of the longitudinal magneto-conductance (Gxx) in a perpendicular magnetic field (i.e. Shubnikov-de Haas oscillations, SdHO) in combination with the Hall resistance (Rxy). Here we discuss the representative data for an intercalated 5L sample patterned into a Hall bar geometry (see Figure 1c and Experimental section). Figure 1b shows SdHO of Gxx as a function of perpendicular magnetic field (B) for different temperatures. It is apparent that for T<10K Gxx oscillates with two distinct frequencies. For T>10K only the lower frequency oscillations are visible. These observations indicate that electrical conduction takes place through parallel gases of charge carriers with distinct densities. Indeed, the Fourier transform of Gxx(1/B) yields peaks at frequencies fSdHO1 = 1100T and fSdHO2 = 55T (see Figure 1d), corresponding to charge carrier densities n1 = (1.07 × 1014 ± 5 × 1011)cm−2 and n2 = (5.3 × 1012 ± 4 × 1011) cm−2 (with ni = 4efSdHOi/h6, 22).

The temperature dependence of the magneto-conductivity oscillations allows us to determine the cyclotron mass of the charge carriers in these parallel gases. Figure 1e and f show the low- and high-frequency magneto-conductivity oscillations for different temperatures (see Experimental Section). In all cases, the temperature decay of the amplitude is well described by A(T)∝T/sinh (2π2kBTmc/eB) (see Figure 1g), with cyclotron masses mc1 = (0.25 ± 0.05)me and mc2 = (0.08 ± 0.001)me for the high- and low-frequency oscillations, respectively. These values correspond to the expected values of cyclotron mass for massless Dirac fermions  at n1 and for chiral massive charge carriers of bilayer graphene

at n1 and for chiral massive charge carriers of bilayer graphene  at n2 (with vF = 106 ms−1 the Fermi velocity6 and γ the interlayer hopping energy15), see Supporting Information. Therefore, intercalation of FeCl3 decouples the stacked 5L graphene into parallel gases of massless (1L) and massive (2L) charge carriers.

at n2 (with vF = 106 ms−1 the Fermi velocity6 and γ the interlayer hopping energy15), see Supporting Information. Therefore, intercalation of FeCl3 decouples the stacked 5L graphene into parallel gases of massless (1L) and massive (2L) charge carriers.

The charge carrier type (electrons or holes) and the number of parallel gases present in FeCl3-FLG are readily identified by correlating SdHO to the Hall resistance measurements. The linear dependence of Rxy(B) with positive slope identifies charge carriers as holes, with a Hall carrier density nH = B/(eRxy) = 3 × 1014cm−2 (see Figure 1c). Since the total carrier density ntot = Σini should be higher than nH = (Σiniμi)2/Σiniμ2i (with ni and μi the carrier density and mobility of each hole gas),23 only a minimum of three parallel hole gases with n1 = 1.07 × 1014cm−2 can explain the estimated value of nH, i.e. 3×n1 +n2 ≥ nH (see Supporting Information). Therefore, the electrical transport characterization demonstrates the presence of four parallel hole gases, of which one with bilayer character (and density n2) and three with monolayer character (each with density n1). These findings are confirmed by the Raman spectra taken after the device fabrication showing the presence of pristine G, G1 and G2 peaks (see Supporting Information). A schematic of this crystal structure is illustrated in Figure 1h. The bilayer gas is likely to be caused by the first two layers of the stacking which have been de-intercalated due to rinsing in acetone during lift-off.19 The bottom part of the stacking has a per-layer doping of n1 = 1.07 × 1014cm−2 and the stoichiometry of stage-1 FeCl3 graphite intercalation compounds (i.e. where each graphene layer is sandwiched by two FeCl3 layers).15 In total we have investigated electrical transport and Raman spectroscopy in more than 10 intercalated 5L samples and in all cases we confirmed the structure reported in Figure 1h.

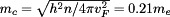

A remarkable property of FeCl3-FLGs shown by the electrical transport characterization is that intercalated materials thicker than 3L invariably exhibit a very low-sheet resistance, which is essential for their use as electrical conductors. We find a room temperature value of Rs = 8.8Ω/□ in 5L intercalated FLGs. The 4L intercalated FLGs typically exhibit higher sheet resistance values than the 5L intercalated samples with a similar crystal structure (see Supporting Information for a comparison between the electrical properties and Raman spectra of several 4L and 5L intercalated FLGs). Furthermore, the sheet resistance of FeCl3-FLGs thicker than 2L decreases when lowering the temperature as expected for metallic conduction (see Figure 2a). Contrary to intercalated samples, pristine FLGs always have a higher Rs (>120 Ω/□) and they exhibit non-metallic behaviour as a function of temperature5, 24, 25 (see Figure 2b). This suggests that the origin of the low values of Rs and the metallic nature of the conduction are consequences of intercalation with FeCl3. FeCl3-FLGs thinner than 3L suffer of partial de-intercalation during the device fabrication, which results in a non-metallic behaviour similar to pristine FLGs and in higher Rs values (see Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

a) Temperature dependence of the square resistance for FeCl3-FLG of different thicknesses. b) Square resistance for pristine FLG of different thicknesses as function of temperature. These devices are fabricated on SiO2/Si substrates and the highly-doped Si substrate is used as a gate to adjust the Fermi level to the charge neutrality of the system. c) Hall resistance of FeCl3-FLG as a function of magnetic field. The inset shows the data for the bilayer sample on a smaller B scale. Panels d) and e) show the carrier density and mobility for FeCl3-FLG as a function of the number of graphene layers.

The low values of Rs characterizing thick FeCl3-FLG are accompanied by an extremely high charge density. Indeed, the Hall coefficient measurements reveal that nH ranges from 3 × 1014cm−2 to 8.9 × 1014cm−2, depending on the number of layers (see Figure 2c and d). These charge densities exceed even the highest values demonstrated so far by liquid electrolyte26 or ionic27 gating. The corresponding charge carrier mobility for the 4L and 5L samples typically ranges from μH = 1540 cm2V−1 s−1 to μH = 3650 cm2V−1 s−1

(μH = 1/(nHeρxx) with ρxx the longitudinal resistivity and e the electron charge). Consequently, the charge carriers in thick FeCl3-FLG have a macroscopic mean free path as high as 0.6 μm in 5L at room temperature. The outstanding electrical properties, e.g. lower Rs than ITO and macroscopic mean free path, found in FeCl3-FLGs thicker than 3L are of fundamental interest for the development of novel electronic applications based on highly conductive materials.

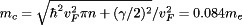

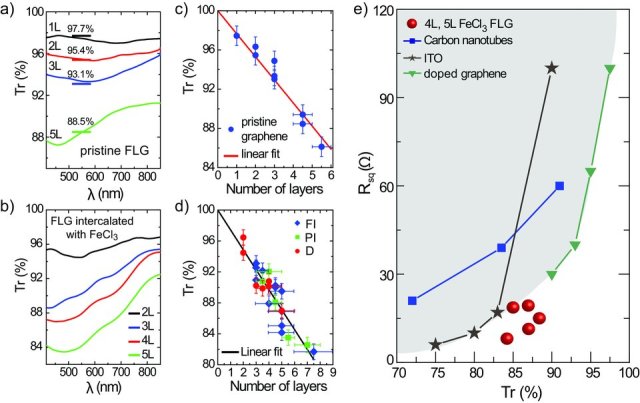

Whether FeCl3-FLGs can replace ITO in optoelectronic applications strongly depends on their optical properties. Surprisingly, our detailed study of the optical transmission in the visible wavelength range shows that while FeCl3 intercalation improves significantly the electrical properties of graphene, it leaves the optical transparency nearly unchanged. Figure 3a and b show a comparison between the transmittance spectra of pristine FLG and FeCl3-FLG. The transmittance values of pristine FLG at the wavelength of 550nm are in agreement with the expected values,4 highlighted in Figure 3a, and with the results reported by other groups.4, 7 Upon intercalation, the transmittance slightly decreases at low wavelengths, but it is still above 80%. In order to measure an accurate value of transmittance we fit it with a linear dependence on the number of layers for a statistical ensemble of flakes (Figure 3d). This results in similar extinction coefficients per layer for pristine FLG (≍2.4 ± 0.1%) and for FeCl3-FLG (≍ 2.6 ± 0.1%), see Figure 3c and d. For wavelengths longer than 550nm we observe an increase in the optical transparency of FeCl3-FLG. This is a significant advantage of our material compared to ITO whose transparency decreases for wavelengths longer than 600nm.2 This property will provide useful applications that require conductive electrodes which are transparent both in visible and near infrared range. For instance, FeCl3-FLG transparent electrodes could be used for solar cells to harvest energy over an extended wavelength range as compared to ITO-based devices, or for electromagnetic shielding in infrared.

Figure 3.

Panels a) and b) show the transmittance spectra of pristine FLG and FeCl3-FLG, respectively. The horizontal lines in b) are the corresponding transmittances at the wavelength of 550nm reported in the literature.4, 7 c) Transmittance at 550nm for pristine FLG as a function of the number of layers. The red line is a linear fit, which gives the extinction coefficient of 2.4 ± 0.1% per layer. d) Transmittance at 550nm for fully intercalated FeCl3-FLG (FI), partially intercalated FeCl3-FLG (PI) and doped FeCl3-FLG (D) as a function of the number of layers. The black line is a linear fit with the extinction coefficient of (2.6 ± 0.1)% per layer. e) Square resistance versus transmittance at 550nm for 4L and 5L FeCl3-FLG (from these experiments), ITO,28 carbon-nanotube films29 and doped graphene materials.7 FeCl3-FLG outperform the current limit of transparent conductors, which is indicated by the grey area.

The high transparency observed in FeCl3-FLG complemented by their remarkable electrical properties makes these materials valuable candidates for transparent conductors. However, to replace ITO in optoelectronic applications, it is generally agreed that materials must (at least) have the properties of commercially available ITO (Rs = 10 Ω/□ and Tr = 85%9). Figure 3e compares Rs vs. Tr of FeCl3-FLG materials with ITO,28 and other promising carbon-based candidates to replace ITO such as carbon-nanotube films29 and doped graphene materials.7 It is apparent that Rs and Tr of FeCl3-FLGs outperform the current limits of ITO and of the best values reported so far for doped graphene.7 Therefore, the outstandingly high electrical conductivity and optical transparency make FeCl3-FLG materials the best transparent conductors for optoelectronic devices.

Finally, an important characteristic required by a transparent conductor is its stability upon exposure to air. In principle FLGs could be intercalated with a large variety of molecules, similar to the graphite intercalation compounds (GIC).15 However, most of the GIC are unstable in air, with donor compounds being easily oxidized and acceptors being easily desorbed. Therefore we studied the stability in air of FeCl3-FLG by performing Raman measurements as a function of time. We found that the Raman spectra of FeCl3-FLG samples show no appreciable changes on a time scale of up to one year (see Supporting Information). This property has important implications for the utilization of these materials as transparent conductors in practical applications such as displays and photovoltaic devices.

In conclusion, we demonstrate novel transparent conductors based on few layer graphene intercalated with ferric chloride with an outstandingly high electrical conductivity and optical transparency. We show that upon intercalation a record low sheet resistance of 8.8Ω/□ is attained together with an optical transmittance higher than 84% in the visible range. These parameters outperform the best values of ITO and of other carbon-based materials. The FeCl3-FLGs materials are relatively inexpensive to make and they are easily scalable to industrial production of large area electrodes. Contrary to the numerous chemical species that can be intercalated into graphite (more than a hundred15), many of which are unstable in air, we found that FeCl3-FLGs are air stable on a timescale of at least one year. Other air stable graphite intercalated compounds can only by synthesized in the presence of Chlorine gas,15 which is highly toxic. On the contrary, here we demonstrate that the intercalation of FLG with FeCl3 is easily achieved without the need of using Chlorine gas, which ensures an environmentally friendly industrial processing. Furthermore, the low intercalation temperature (360°) required in the processing allows the use of a wide range of transparent flexible substrates which are compatible with existing transparent electronic technologies. These technological advantages combined with the unique electro-optical properties found in FeCl3-FLG make these materials a valuable alternative to ITO in optoelectronics.

Experimental Section

Sample fabrication: The intercalation process with FeCl3 is performed in vacuum. Both anhydrous FeCl3 powder and the substrate with exfoliated FLG are positioned in different zones inside a glass tube. The tube is pumped down to 2 ×10−4mbar at room temperature for 1 hour to reduce the contamination by water molecules. Subsequently, the FLG and the powder are heated for 7.5 hours at 360° and 310°, respectively. A heating rate of 10°/min is used during the warming and cooling of the two zones. Ohmic contacts are fabricated on FeCl3-FLG by means of electron-beam lithography and lift-off of thermally evaporated chrome/gold bilayer (5/50 nm). We have fabricated FeCl3-FLG on both SiO2/Si and glass substrates and we found no significant differences in their transport properties.

Raman measurements: Raman spectra are collected in ambient air and at room temperature with a Renishaw spectrometer. An excitation laser with a wavelength of 532 nm, focused to a spot size of 1.5 μm diameter and a ×100 objective lens are used. To avoid sample damage or laser induced heating, the incident power is kept at 5 mW.

Electrical measurements: The longitudinal and the Hall resistances are studied in a 4-probe configuration by applying an a.c. current bias and measuring the resulting longitudinal and transversal voltages with a lock-in amplifier. The excitation current is varied to ensure that the energy range where electrical transport takes place is smaller than the energy range associated to the temperature of the electrons. This prevents heating of the electrons and the occurrence of nonequilibrium effects. Since conductances are additive, the analysis of Shubnikov-de Haas oscillations is performed on the longitudinal conductivity σxx = ρxx/[ρ2xx + ρ2xy] (with ρxx and ρxy the longitudinal and transversal resistivity, respectively). The low frequency magneto-conductivity oscillations shown in Figure 2d are obtained by averaging out the high frequency oscillations, whereas to obtain the high frequency oscillations shown in Figure 2e we subtract the low frequency oscillations from the longitudinal conductivity.

Transmission measurements: The transmission of pristine FLG and FeCl3-FLG is characterized by measuring the bright-field transmission spectra. A system based on an inverted optical microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U) combined with a spectrometer and charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (Princeton Instruments, SpectraPro 2500i) is used to acquire data. White light from a tungsten filament lamp is used to illuminate the samples and, after passing through the sample, is collected by a dry Nikon lens (S Plan Fluor ELWD) ×40 of numerical aperture 0.60. A slit width of 50 μm is used for the spectrometer, yielding a spectral resolution < 1 nm for the measurements. In the spectrometer the dispersed light is projected onto the 1024 × 256 lines of the CCD camera. Data from the camera are extracted to give the transmission spectra of the flake, or part of it, the data being normalized to the signal obtained through a region of bare substrate. For the visually uniform parts of the flakes, spectra are averaged along several lines of the CCD camera to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Paul Wilkins for technical support. This work was financially supported by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (Grants No. EP/G036101/1 and no. EP/J000396/1) and by the Royal Society (Research Grants 2010/R2 no. SH-05052 and 2011/R1 no. SH-05323).

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Supplementary material

Detailed facts of importance to specialist readers are published as ”Supporting Information”. Such documents are peer-reviewed, but not copy-edited or typeset. They are made available as submitted by the authors.

References

- 1.Kumar A, Zhou C. ACS Nano. 2010;4:11. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hecht DS, Hu L, Irvin G. Adv. Mater. 2011;23:1482. doi: 10.1002/adma.201003188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wassei JK, Kaner RB. Mater. Today. 2010;13:52. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nair RR, Blake P, Grigorenko AN, Novoselov KS, Booth TJ, Stauber T, Peres NMR, Geim AK. Science. 2008;320:1308. doi: 10.1126/science.1156965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Novoselov KS, Geim AK, Morozov SV, Jiang D, Zhang Y, Dubonos SV, Grigorieva IV, Firsov AA. Science. 2004;306:666. doi: 10.1126/science.1102896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Novoselov KS, Geim AK, Morozov SV, Jiang D, Katsnelson MI, Grigorieva IV, Dubonos SV, Firsov AA. Nature. 2005;438:197. doi: 10.1038/nature04233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bae S, Kim H, Lee Y, Xu X, Park J-S, Zheng Y, Balakrishnan J, Lei T, Kim HR, Song YI, Kim Y-J, Kim KS, Ozyilmaz B, Ahn J-H, Hong BH, Iijima S. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2010;5:574. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee C, Wei X, Kysar JW, Hone J. Science. 2008;321:385. doi: 10.1126/science.1157996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De S, Coleman JN. ACS Nano. 2010;4:2713. doi: 10.1021/nn100343f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim KK, Reina A, Shi Y, Park H, Li L-J, Lee YH, Kong J. Nanotechnology. 2010;21:285205. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/21/28/285205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kasry A, Kuroda MA, Martyna GJ, Tulevski GS, Bol AA. ACS Nano. 2010;4:3839. doi: 10.1021/nn100508g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, Tong SW, Xu XF, Ozyilmaz B, Loh KP. Adv. Mater. 2011;23:1514. doi: 10.1002/adma.201003673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao W, Tan PH, Liu J, Ferrari AC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:5941. doi: 10.1021/ja110939a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhan D, Sun L, Ni ZH, Liu L, Fan XF, Wang Y, Yu T, Lam YM, Huang W, Shen ZX. Adv. Func. Mat. 2010;20:3504. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dresselhaus MS, Dresselhaus G. Adv. Phys. 2002;51:1. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrari AC, Meyer JC, Scardaci V, Casiraghi C, Lazzeri M, Mauri F, Piscanec S, Jiang D, Novoselov KS, Roth S, Geim AK. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006;97:187401. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.187401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malard LM, Pimenta MA, Dresselhaus G, Dresselhaus MS. Phys. Rep. 2009;473:51. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koh YK, Bae M-H, Cahill DG, Pop E. ACS Nano. 2011;5:269. doi: 10.1021/nn102658a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim N, Kim KS, Jung N, Brus L, Kim P. Nano Lett. 2011;11:860. doi: 10.1021/nl104228f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howard CA, Dean MPM, Withers F. Phys. Rev. B. 2011;84:241404. (R) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jung N, Kim B, Crowther AC, Kim N, Nuckolls C, Brus L. ACS Nano. 2011;5:5708. doi: 10.1021/nn201368g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Tan Y-W, Stormer HL, Kim P. Nature. 2005;438:201. doi: 10.1038/nature04235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davies JH. The Physics of Low-Dimensional Semiconductors. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Craciun MF, Russo S, Yamamoto M, Oostinga JB, Morpurgo AF, Tarucha S. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009;4:383. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu W, Perebeinos V, Freitag M, Avouris P. Phys. Rev. B. 2009;80:235402. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Efetov DK, Kim P. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010;105:256805. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.256805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ye J, Craciun MF, Koshino M, Russo S, Inoue S, Yuan H, Shimotani H, Morpurgo AF, Iwasa Y. PNAS. 2011;108:13002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018388108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee J-Y, Connor ST, Cui Y, Peumans P. Nano Lett. 2008;8:689. doi: 10.1021/nl073296g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hecht DS, Heintz AM, Lee R, Hu L, Moore B, Cucksey C, Risser S. Nanotechnology. 2010;22:075201. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/22/7/075201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.