Abstract

Objective

A 2-wave longitudinal study of young adolescents was used to test whether peer victimization predicts depressive symptoms, depressive symptoms predict peer victimization, or the two constructs show reciprocal relations.

Method

Participants were 598 youths in grades 3 through 6, ages 8 to 14 (M = 10.9, SD = 1.2) at wave 1. The sample was 50.7% female and 90.3% Caucasian. Participants completed self-reports of depressive symptoms, and self-reports and peer nomination measures of physical and relational peer victimization at two time points separated by one year.

Results

(a) depressive symptoms predicted change in both physical and relational victimization but neither type of peer victimization predicted change in depressive symptoms; (b) depressive symptoms were more predictive of physical victimization for boys than for girls; and (c) boys experienced more physical victimization, and girls experienced more relational victimization.

Conclusions

Expression of some depressive symptoms may represent signs of vulnerability. For boys, they may also represent a violation of gender stereotypes. Both factors could be responsible for these effects. Implications for intervention include the possibility that treatment of depression in young adolescents may reduce the likelihood of peer victimization.

Keywords: Peer relations, victimization, depression, cognition, children and adolescents

The effects of peer victimization can be substantial, sometimes dramatically affecting victims’ academic, social, and psychological development (Ross, 2006). Peer victimization occurs relatively frequently, with some studies suggesting prevalence rates of 30 to 60% per semester (e.g., Rigby, 2000). The probability of being victimized by one’s peers peaks during middle childhood and early adolescence (Crick, Casas, & Ku, 1999), which are also key periods for the emergence of depression (e.g., Gotlib & Hammen, 2009). Furthermore, peer victimization is more strongly correlated with depression than with many other narrow-band internalizing problems (e.g., Hawker & Boulton, 2000).

Theoretically, prospective effects between peer victimization and depression may run in either direction. On the one hand, peer victimization could have depressogenic effects, through a variety of mechanisms. To prevent peer aggression, victims may avoid social situations where victimization may occur, but in the process reduce opportunities for positive social interactions, generating an interpersonal mechanism for depression (Lewinsohn & Graf, 1973). Victimization can also convey negative self-relevant information to the victim, which may be internalized by the victim, paving a cognitive pathway to depression (Adams & Bukoski, 2008; Hammen, 2005; Reijntjes, Kamphuis, Prinzie & Telch, 2010). On the other hand, depressive symptoms could elicit victimization. Expression of depressive symptoms could be seen as a sign of weakness indicating that the potential victim would be unable to defend him- or herself (Finnegan, Hodges, & Perry, 1996; Sweeting, Young, West, & Der, 2006).

Several longitudinal studies have been conducted to identify the direction of causality, many of which were reviewed in a recent meta-analysis (Reijntjes et al., 2010). These authors found significant, small to moderate effect sizes in both directions; however, Reijntjes et al. (2010) noted several limitations of their review. First, because of the small number of studies available, Reijntjes et al. (2010) were not able to examine differences between subtypes of victimization such as overt/physical victimization (when a child is physically harmed or controlled by physical threats or attacks) and covert/relational victimization (behavior intended to damage peer relationships, friendships, and social acceptance; Crick & Bigbee, 1998). Some evidence suggests that the relation between relational victimization and depression may be stronger than the relation between physical victimization and depression (Cole, Maxwell, Dukewich, & Yosick, 2010). Second, Reijntjes et al. noted that these relations may also vary by gender. Overt/physical victimization is more closely linked to male gender stereotypes, and covert/relational victimization is more closely linked to female gender stereotypes. Male gender stereotypes, for instance, emphasize the importance of being physically strong (Maccoby, 1998). Hence, symptoms of depression such as public tearfulness and sadness may be more of a violation of male than female social norms, and thus elicit more victimization of boys than girls. Conversely, girls who exhibit such behaviors may actually engender a degree of social support from peers, particularly females. Thus, the effects of physical victimization on depression may differ as a function of the type of victimization and gender.

Third, Reijntjes et al.’s (2010) analyses focused on broadband internalizing problems rather than depression per se. Hawker and Boulton’s (2000) review, however, found that narrow-band depression had a particularly strong cross-sectional relation with peer victimization. Given that different processes are associated with different narrow-band internalizing dimensions (e.g., Marien & Bell, 2004), research focusing specifically on depression is important. Consequently, the overarching purpose of the present study was to examine reciprocal prospective relations between peer victimization and depression symptoms.

Specific goals of the current study then were (a) to evaluate the prospective relation of overt/physical and covert/relational peer victimization to the narrow-band domain of depressive symptoms, (b) to estimate the reciprocal longitudinal relation of peer victimization to depression, and (c) to test the main effects and moderating effects of gender. In addition, we assessed the generalizability of results across methods of measuring peer victimization, specifically peer nomination versus self-report. No single informant is bias free (e.g., self-reports may be susceptible to self-enhancement bias, whereas peer nominations may be influenced by reputation effects); therefore assessing the generalizability of effects across different informants is important (De Los Reyes & Prinstein, 2004). We focused on middle-school children, an age-range when the effects of victimization are particularly strong (Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2006), using a two-wave, longitudinal design, with self- and peer reports of peer victimization and self-reports of depressive symptoms.

Methods

Participants

We recruited students from two middle Tennessee rural/suburban elementary schools, and the middle school into which they would matriculate. Consent forms were sent home to parents of 720 students. Of these, 83.1% (598 students) obtained parental consent, provided informed assent, and participated in the study. In Wave 1, participants were in grades three (25.7%), four (26.3%), five (25.5%), and six (22.5%), aged 8 to 14 (M = 10.8, SD = 1.2), 49.3% were male. The sample was 90.3% Caucasian, 2.3% African American, 4.4% Hispanic, 0.3% Asian students, and 2.7% other or mixed. The number of children living at home ranged from 1 to 9 (M = 2.9, SD = 1.5). Socio-economic data were not available from the participants (as they were elementary and middle school children) but the median family income for the surrounding area was $55,000, with 16% living below the poverty threshold. Approximately 42.6% of students at participating schools received free or reduced fee lunches.

From Wave 1 to Wave 2, 9.8% of participants dropped out, primarily due to families moving out of district. At Wave 2, we added new participants, primarily students who had moved into the district since Wave 1. Participants on whom we had no missing data (n = 466), participants on whom we had Wave 1 but no Wave 2 data (n = 57), and participants on whom we had Wave 2 but no Wave 1 data (n = 75) did not differ significantly on any variable. We used full information maximum likelihood estimation to reduce the likelihood of bias due to the possibility of nonrandom patterns of missingness.

Measures

Victimization by peers

Self-reports and peer nominations were used to assess peer victimization. Our self-report measure contained 6 items designed to assess relational and physical victimization (RV-SR and PV-SR, respectively), expanding on items used by Ladd and Kochenderfer-Ladd (2002) to reflect a broader range of physical and relational victimization. The question stem was “Does anyone in your class ever….” The three relational items were: (1) Tell others to stop being your friend, (2) Say you can’t play with them, and (3) Say mean things to others kids about you. The three physical items were (4) Kick you, (5) Hit you, and (6) Push you. Each item was rated on a 4-point scale. Items were summed to form subscale score totals. Cronbach’s alphas at Waves 1 and 2 were 0.76 and 0.77 for relational victimization and 0.81 and 0.86 for physical victimization, respectively. Principle axis factor analysis with oblimin rotation produced a 2-factor structure with primary factor loadings above 0.50 on the appropriate factors, and no cross loadings greater than 0.25. The two factors correlated 0.44 and 0.51 for Time 1 and Time 2, respectively.

The peer nomination measure used Coie, Dodge, and Coppotelli (1982a) format. Each participant received a list of at least 20 names of other students primarily from the respondent’s home room. If there were not 20 consented participants from the home room names were added from adjacent classrooms.1 Separate forms were used for relational and physical victimization. The physical victimization item was: “Some kids get picked on or hurt by other kids at school. They might get pushed around. They might get bullied by others. They might even get beaten up. Who gets treated like this? Who gets pushed around or bullied by others?” The relational victimization item that followed was: “Some kids get picked on by other kids at school in different ways. They might get ignored, talked about or made fun of. Other kids may say or do mean things behind their backs. They may even be left out or kicked out of groups.” Respondents were asked to mark all the names of classmates who fit each description. Scores for each student were the proportion of 20 nominators who indicated that the student was either physically or relationally victimized. KR-20 reliabilities were 0.82 and 0.85, respectively.

Depressive symptoms

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1985) is a widely used 27-item self-report measure. At the request of the school system, the suicide item was dropped. CDI items consist of three statements graded in order of increasing severity, scored from 0 to 2. Children select one sentence from each group that best describes themselves for the past two weeks (e.g., “I am sad once in a while,” “I am sad many times,” or “I am sad all the time”). Items were summed to form a total CDI score. The CDI has high levels of reliability and validity (e.g., Craighead, Smucker, Craighead & Ilardi, 1998). At both time points, Cronbach’s alpha for the 26-item version of this measure was .92.

Procedures

The time interval between the two waves of data collection was approximately one year. Prior to both data collections, we distributed consent forms to children in participating classrooms to take home to parents. We offered a $100 donation to each classroom if 90% of children returned consent forms signed by their guardian, either granting or denying permission for participation. For third- and fourth-graders, a research assistant read the questionnaires to a group of students. For students in the fifth through seventh grades, a research assistant introduced the battery and allowed students to work at their own pace. At all grade levels research assistants circulated among students to answer questions. At the end of the administration, the students were given snacks and a decorated pencil for their participation.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 displays means, standard deviations, and correlations at each time point, by gender. Box’s test of homogeneity of covariances indicated significant differences between the covariance matrices for the males and females (χ215 = 82.35, p < .001), suggesting that gender might serve as a moderator in subsequent regression analyses. Hotelling’s T2 tests revealed significant mean gender differences at both Wave 1 T25,517 = 14.72 and Wave 2, T25,535 = 6.55, respectively (ps < .001), with boys having higher levels of physical victimization on both self-report and peer nomination measures, and girls having higher levels of relational victimization on self-report measures.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations (SDs), and Correlations for Boys (Below Diagonal) and Girls (Above Diagonal)

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CDI Wave 1 (SR) | 1.00 | 0.42 | 0.47 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.60 | 0.42 | 0.39 | 0.40 | 0.32 |

| 2. Phy PV Wave 1 (SR) | 0.39 | 1.00 | 0.43 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.28 | 0.30 | 0.26 |

| 3. Rel PV Wave 1 (SR) | 0.56 | 0.43 | 1.00 | 0.29 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.49 | 0.28 | 0.37 |

| 4. Phy PV Wave 1 (PN) | 0.42 | 0.47 | 0.33 | 1.00 | 0.70 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 0.49 | 0.64 |

| 5. Rel PV Wave 1 (PN) | 0.34 | 0.41 | 0.35 | 0.56 | 1.00 | 0.25 | 0.16 | 0.27 | 0.41 | 0.52 |

| 6. CDI Wave 2 (SR) | 0.62 | 0.08 | 0.33 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 1.00 | 0.40 | 0.46 | 0.29 | 0.33 |

| 7. Phy PV Wave 2 (SR) | 0.28 | 0.42 | 0.29 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.43 | 1.00 | 0.58 | 0.36 | 0.31 |

| 8. Rel PV Wave 2 (SR) | 0.52 | 0.16 | 0.56 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.51 | 0.40 | 1.00 | 0.30 | 0.34 |

| 9. Phy PV Wave 2 (PN) | 0.20 | 0.41 | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 1.00 | 0.73 |

| 10. Rel PV Wave 2 (PN) | 0.34 | 0.40 | 0.23 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.40 | 0.34 | 0.35 | 0.68 | 1.00 |

| Boys' means | 7.73 | 4.99a | 5.34a | 0.08a | 0.05 | 7.11 | 4.85b | 5.83b | 0.09b | 0.13 |

| Boys' SDs | 8.49 | 2.37 | 2.07 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 8.29 | 2.35 | 2.22 | 0.15 | 0.18 |

| Girls' means | 8.99 | 4.29a | 6.46a | 0.05a | 0.06 | 8.37 | 4.35b | 6.29b | 0.05b | 0.14 |

| Girls' SDs | 9.50 | 1.95 | 2.82 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 9.39 | 2.08 | 2.34 | 0.10 | 0.17 |

Note. Phy PV= Physical peer victimization; Rel PV= Relational peer victimization; SR = self-report; PN = peer nomination. All correlations are significant at p < .05. Means with same superscript in same column contributed significantly to the multivariate gender difference at that wave.

Longitudinal predictive relations

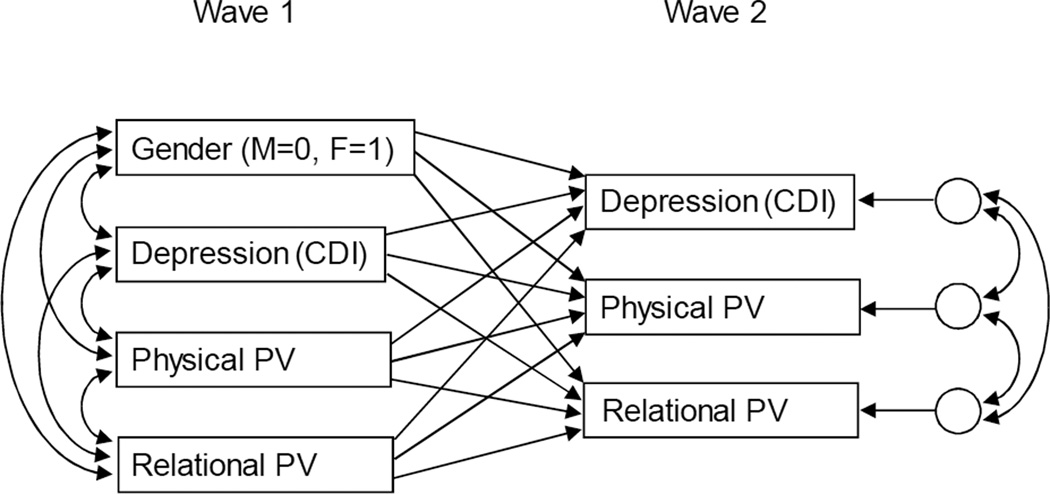

We first assessed (a) whether peer victimization longitudinally predicted depressive symptoms, and (b) whether depressive symptoms longitudinally predicted peer victimization. We used the saturated path analytic model in Figure 1 in which Wave 2 depressive symptoms, physical peer victimization, and relational peer victimization were simultaneously regressed onto Wave 1 depressive symptoms, physical peer victimization, relational peer victimization, and gender. In the first analysis, all measures of depression and peer victimization were self-reports (see top half of Table 2). Path coefficients were estimated for this just-identified model using LISREL 8.53 (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 2002). In the prediction of Wave 2 CDI, only Wave 1 CDI was significant. In the prediction of Wave 2 physical peer victimization, significant predictors were gender (with boys reporting a greater increase in physical peer victimization than girls), Wave 1 CDI, and Wave 1 physical peer victimization. In prediction of Wave 2 relational peer victimization, significant predictors were Wave 1 CDI and Wave 1 relational peer victimization. The effect of CDI on relational peer victimization was not significantly different from the effect of CDI on physical peer victimization (p > .20).

Figure 1.

Manifest variable path diagram estimating effects of physical and relational TPV on depressive symptoms and vice versa.

Table 2.

Predicting Wave 2 Depressive Symptoms, Physical PV, and Relational PV with Wave 1 Selfreport (SR) and Peer Nomination (PN) Measures – As in Figure 1.

| Predictor variables | → | Dependent variables | B | SE(B) | β | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Using self-reports to measure PV | ||||||

| Gender | → | CDI Wave 2 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.56 |

| CDI Wave 1 | → | CDI Wave 2 | 0.63 | 0.06 | 0.64 | 11.18*** |

| Physical PV Wave 1 | → | CDI Wave 2 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 1.14 |

| Relational PV Wave 1 | → | CDI Wave 2 | −0.03 | 0.06 | −0.03 | −0.48 |

| Gender | → | Physical PV Wave 2 | −0.22 | 0.10 | −0.11 | −2.19* |

| CDI Wave 1 | → | Physical PV Wave 2 | 0.25 | 0.07 | 0.24 | 3.59*** |

| Physical PV Wave 1 | → | Physical PV Wave 2 | 0.31 | 0.07 | 0.30 | 4.58*** |

| Relational PV Wave 1 | → | Physical PV Wave 2 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.83 |

| Gender | → | Relational PV Wave 2 | −0.08 | 0.09 | −0.05 | −0.97 |

| CDI Wave 1 | → | Relational PV Wave 2 | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 3.82*** |

| Physical PV Wave 1 | → | Relational PV Wave 2 | −0.03 | 0.06 | −0.03 | −0.50 |

| Relational PV Wave 1 | → | Relational PV Wave 2 | 0.40 | 0.06 | 0.45 | 6.97*** |

| Using peer nominations to measure PV | ||||||

| Gender | → | CDI Wave 2 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.18 |

| CDI Wave 1 | → | CDI Wave 2 | 0.62 | 0.05 | 0.62 | 12.47*** |

| Physical PV Wave 1 | → | CDI Wave 2 | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.01 | −0.24 |

| Relational PV Wave 1 | → | CDI Wave 2 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 1.45 |

| Gender | → | Physical PV Wave 2 | −0.26 | 0.09 | −0.13 | −2.93** |

| CDI Wave 1 | → | Physical PV Wave 2 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 2.76** |

| Physical PV Wave 1 | → | Physical PV Wave 2 | 0.30 | 0.06 | 0.30 | 5.36*** |

| Relational PV Wave 1 | → | Physical PV Wave 2 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 2.40* |

| Gender | → | Relational PV Wave 2 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.85 |

| CDI Wave 1 | → | Relational PV Wave 2 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 3.06** |

| Physical PV Wave 1 | → | Relational PV Wave 2 | 0.36 | 0.05 | 0.36 | 6.74*** |

| Relational PV Wave 1 | → | Relational PV Wave 2 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.17 | 3.28*** |

Note. PV = peer victimization; CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory; std = standardized based on Wave 1 means and standard deviations.

We repeated this analysis replacing the self-report measures of peer victimization with the peer nomination measures (see bottom half of Table 2). Most of the previous results were replicated. In predicting Wave 2 CDI, only Wave 1 CDI was significant. In predicting Wave 2 physical peer victimization, significant predictors were gender, Wave 1 CDI, and physical victimization, and relational victimization. In predicting Wave 2 relational peer victimization, significant predictors were Wave 1 CDI, relational victimization, and physical victimization. The effect of CDI on relational victimization was not significantly different from the effect of CDI on physical victimization (p > .20). Higher scores on Wave 1 CDI predicted higher levels of Wave 2 physical and relational peer victimization. Results for self-report versus peer nomination measures of peer victimization were very similar.2

The preceding analyses tested unique effects of relational and physical peer victimization (i.e., each type of victimization was statistically controlled when testing effects of the other type). We repeated these analyses ignoring (i.e., not including in the model) the effects of the other type of peer victimization. Similar to the prior analyses, effects of relational and physical victimization at Wave 1 on the CDI at Wave 2 were nonsignificant (ps > .20), regardless of whether victimization was measured by self-report or peer nomination. Specific parameter estimates are not presented as the results were very similar to those in Table 2.

Moderating effects of gender

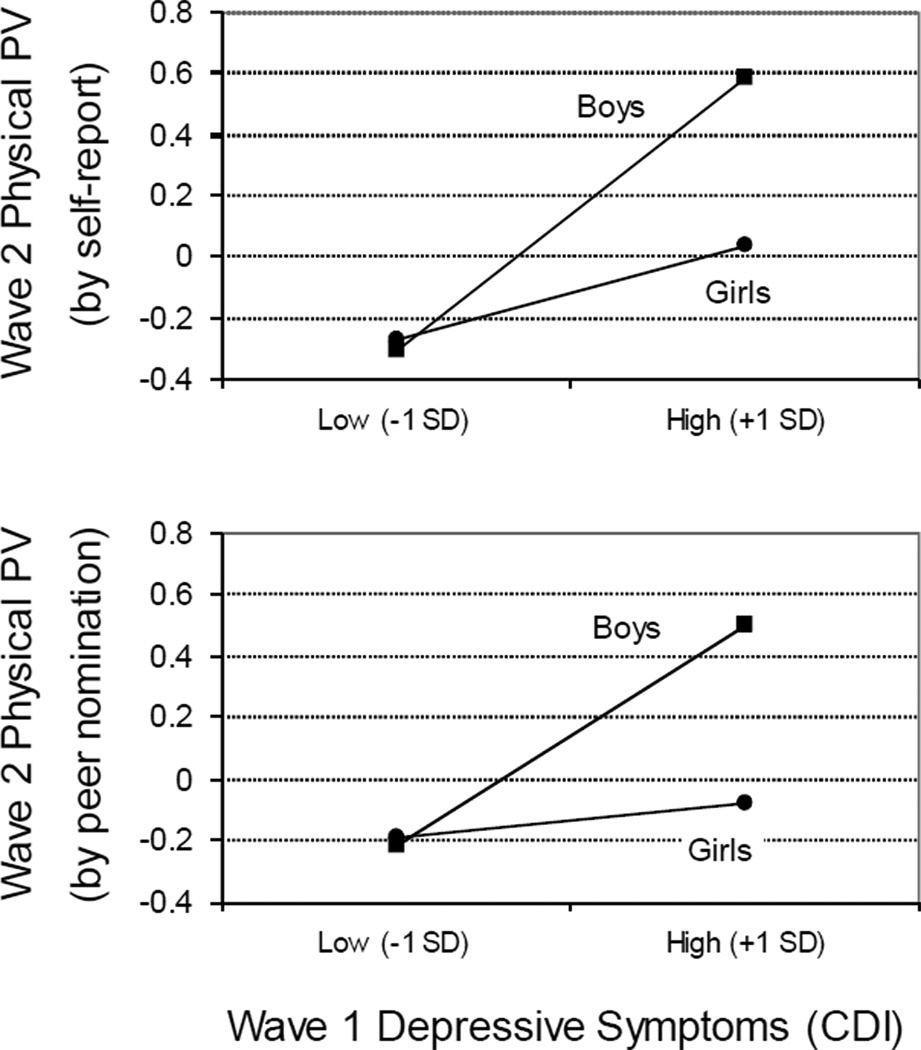

After centering all variables at their means, we computed product terms for gender×Wave 1 depression, gender×Wave 1 physical peer victimization, and gender×Wave 1 relational peer victimization, adding them to the left side of the path diagram in Figure 1 as predictors of Wave 2 measures. This path analysis was conducted twice, once on the self-report measures and once on the peer nomination measures. Gender×depression interactions were significant in the prediction of Wave 2 self-reported and peer-nominated physical peer victimization (see panels 1 and 3 of Table 3). The relation of Wave 1 depression to Wave 2 physical peer victimization was significantly stronger for boys than for girls (see Figure 2) for self-report (Bboys = 0.45, p < .001; Bgirls = 0.15, p < .05) and peer nomination (Bboys = 0.36, p < .001; Bgirls = 0.06, ns). That is, boys who were more depressed at wave one were more likely to be physically victimized at Wave 2, compared to girls at the same levels of depression. At relatively low levels of depressive symptoms (1 SD below the Wave 1 mean), gender differences in physical peer victimization were negligible; however, at relatively high levels of depressive symptoms (1 SD above the mean), physical victimization was approximately 0.3 SD higher for boys than for girls.3

Table 3.

Gender as Moderator of Wave 1 CDI and PV Effects on Wave 2 Relational and Physical PV, Using Self-report (SR) and Peer Nomination (PN) measures.

| Predictor | B | SE(B) | β | t | p< |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DV = Self-report of Physical PV Wave 2 (std) | |||||

| intercept | 0.14 | 0.07 | 1.90 | 0.058 | |

| Gender (0=boy, 1=girl) | −0.26 | 0.10 | −0.13 | −2.52 | 0.012 |

| Relational PV Wave 1 (SR) | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 1.20 | 0.229 |

| Physical PV Wave 1 (SR) | 0.22 | 0.09 | 0.20 | 2.37 | 0.018 |

| CDI Wave 1 (SR) | 0.45 | 0.10 | 0.41 | 4.34 | 0.001 |

| Gender × Relational PV | −0.13 | 0.15 | −0.09 | −0.84 | 0.398 |

| Gender × Physical PV | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 1.10 | 0.273 |

| Gender × CDI | −0.30 | 0.14 | −0.19 | −2.12 | 0.034 |

| DV = Self-report of Relational PV Wave 2 (std) | |||||

| intercept | 0.10 | 0.06 | 1.65 | 0.100 | |

| Gender (0=boy, 1=girl) | −0.13 | 0.09 | −0.07 | −1.49 | 0.137 |

| Relational PV Wave 1 (SR) | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.52 | 5.01 | 0.001 |

| Physical PV Wave 1 (SR) | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.66 | 0.508 |

| CDI Wave 1 (SR) | 0.21 | 0.09 | 0.22 | 2.40 | 0.016 |

| Gender × elational PV | −0.10 | 0.13 | −0.08 | −0.83 | 0.408 |

| Gender × Physical PV | −0.24 | 0.11 | −0.15 | −2.07 | 0.039 |

| Gender × CDI | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.27 | 0.790 |

| DV = Peer Nomination of Physical PV Wave 2 (std) | |||||

| intercept | 0.14 | 0.06 | 2.39 | 0.017 | |

| Gender (0=boy, 1=girl) | −0.27 | 0.09 | −0.13 | −3.15 | 0.002 |

| Relational PV Wave 1 (PN) | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.71 | 0.478 |

| Physical PV Wave 1 (PN) | 0.41 | 0.08 | 0.40 | 5.00 | 0.001 |

| CDI Wave 1 (SR) | 0.36 | 0.09 | 0.34 | 4.21 | 0.001 |

| Gender × Relational PV | 0.08 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.68 | 0.494 |

| Gender × Physical PV | −0.25 | 0.13 | −0.15 | −1.93 | 0.053 |

| Gender × CDI | −0.30 | 0.12 | −0.21 | −2.61 | 0.009 |

| DV = Peer nomination of Relational PV Wave 2 (std) | |||||

| intercept | −0.04 | 0.06 | −0.62 | 0.537 | |

| Gender (0=boy, 1=girl) | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.73 | 0.468 |

| Relational PV Wave 1 (PN) | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 1.25 | 0.212 |

| Physical PV Wave 1 (PN) | 0.49 | 0.08 | 0.48 | 6.22 | 0.001 |

| CDI Wave 1 (SR) | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 1.88 | 0.060 |

| Gender × Relational PV | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.81 | 0.417 |

| Gender × Physical PV | −0.30 | 0.12 | −0.18 | −2.38 | 0.017 |

| Gender × CDI | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.32 | 0.749 |

Note. In the prediction of depressive symptoms, all gender × victimization interactions were nonsignificant. PV = peer victimization; CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory; std = standardized based on Wave 1 means and standard deviations.

Figure 2.

Gender moderates the relation of wave 1 depressive symptoms to wave 2 physical victimization (measured by self-report and peer nomination).

Discussion

Three primary findings emerged from this study. First, symptoms of depression predicted changes in physical and relational peer victimization, but peer victimization did not predict changes in symptoms of depression. Second, gender moderated the relation between depressive symptoms and physical victimization, with depressive symptoms more predictive of physical victimization for boys than for girls. Third, there were significant gender effects on victimization, with boys reporting higher levels of physical victimization for both self-report and peer nomination, and girls reporting higher levels of relational victimization, for self-report.

This first finding supported the idea that the expression of depressive symptoms increases the likelihood of being victimized by peers. Our results showed that depressive symptoms predicted changes in peer victimization. The direction and strength of this relation did not differ by type of victimization. These results expand upon previous work in that we found significant prospective effects even when using qualitatively different methods to assess victimization and depression (cf. McLaughlin, Hatzenbuehler, & Hilt, 2009; Sweeting et al., 2006). Our results also expand upon other studies that found similar effects but did not focus specifically on depression (e.g., Storch, Masia-Warner, Crisp, & Klein, 2005).

In contrast to some previous studies, the present study did not find that peer victimization significantly predicted changes in depressive symptoms. Discrepant findings are often the result of methodological differences such as time lag and assessment method (Cole & Maxwell, 2009; De Los Reyes & Prinstein, 2004). Some studies (e.g., Sweeting et al., 2006) used longer time lags, and others (e.g., McLaughlin et al., 2009) used shorter time lags, suggesting that our failure to find an effect is not simply a matter of our time lag. Some previous studies that reported a significant effect of victimization on depression used a mono-method design (e.g., Hodges & Perry, 1999), which may have inflated the effect, but other studies used multi-method designs (e.g., Schwartz, Gorman, Nakamoto & Toblin, 2005). One implication of this variability is that moderators of the effect of victimization on depression may be important, which is supported by the results of studies such as Isaacs, Hodges and Salmivalli (2008) and Card and Hodges (2007).

Gender moderated the relation between depressive symptoms and physical victimization. Depressive symptoms were more predictive of subsequent physical victimization for boys than for girls. One explanation is that peers may see depressive symptoms as a sign of weakness or vulnerability particularly for boys, given gender role expectations, suggesting that a boy displaying depressive symptoms is an easy target for victimization. Alternatively, a display of depressive symptoms by males may be seen by peers as a violation of male gender stereotypes, and thus deserving of attack (Card, & Hodges, 2008).

Finally, we found significant overall gender differences on most measures of relational and physical victimization. At both waves, boys were physically victimized more than girls (according to both self-report and peer nomination measures), and girls experienced more relational victimization than did boys (for self-report measures). Longitudinal analyses further revealed that gender predicted changes in physical victimization, with boys becoming more aggressive over time than did girls. These results expand upon literature reviews of peer victimization by Hawker and Boulton (2000) and Reijntjes et al. (2010) and complement two meta-analyses on the perpetration of peer aggression by Archer (2004) and Card, Stucky, Sawalani, and Little (2008). In kindergarten, gender differences in victimization are negligible, with about 20% of both boys and girls experiencing moderate to severe levels of victimization (Kochenderfer & Ladd, 1996). During middle childhood, however, most peer interaction occurs in same-sex groups (Maccoby, 1998). As boys perpetrate more physical aggression than do girls at this age (Archer, 2004; Card et al., 2008), boys are likely to experience more peer victimization in middle childhood. Our data support this speculation, showing that by most (but not all) sources of information boys receive more physical victimization than do girls, whereas girls receive more relational victimization than do boys.

These findings have implications for prevention and intervention efforts. Our results suggest that helping children cope with depression is important not only because of the direct effect on mental health but because such interventions may prevent peer victimization as well. This finding may even be useful in the marketing of depression intervention programs to reluctant schools or families. Our results alos suggest another important line of future research, the identification of specific characteristics of depressed children that are responsible for their increased victimization. Depression is often a subtle disorder, not likely to leap to the attention of child or adolescent peers (as compared to conduct disorder, for instance). Perhaps the more overt signs of dysphoria, such as crying or social withdrawal, are the symptoms that serve as social signs of weakness or vulnerability, leading to increased victimization.

Several limitations of this study suggest areas for future research. First, the magnitude of the prospective relation between depression and peer victimization undoubtedly varies with the length of time between assessments. Our two-wave longitudinal study spanned one year, over which time we found evidence that depression predicted peer victimization but not vice versa. An important direction for future research may be to examine more intensively the temporal dynamics of the potentially reciprocal predictive relations between victimization and depression. Second, our sample was representative of the community in which the data were collected (suburban and rural Tennessee) but the generalizability of our results to more diverse populations is unclear. And finally, we primarily focused on main effects but there may be moderators of the victimization-depression relation, such as friendship status (Hodges, Boivin, Vitaro, & Bukowski, 1999), family support (Isaacs et al., 2008), and relationship context (Card & Hodges, 2007). Thus, an important area for future research will be elucidating the complexity of the relation between peer victimization and depression.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a gift from Patricia and Rodes Hart, and by NICHD grant 1R01HD059891 to David A. Cole. The first and third authors of this report were supported during the conduct of this research in part by NIH Fogarty International Center grant D43-TW007769 to Bahr Weiss.

Footnotes

These were relatively small schools, in which pairs of teachers in adjacent classrooms frequently combined their students for various activities every day. Thus, in many ways adjacent classrooms functioned like one larger class with two teachers. Students in adjacent classrooms knew each other quite well. Class sizes were typically around 25. Our high consent rate meant that at most we added 4 names from adjacent classrooms. (With only 24% of the classrooms requiring additional names, the modal number of added names was actually zero.)

The only substantive difference was that relational peer victimization predicted physical peer victimization and physical peer victimization predicted relational peer victimization when we used peer nomination measures, but not when we used self-report measures

The only other moderator effect involved the gender×physical peer victimization interaction in the prediction of Wave 2 relational peer victimization. This effect was significant in both the analysis of self-reported and peer-nominated peer victimization (see panels 2 and 4 of Table 3). In both analyses, the relation of Wave 1 physical peer victimization to Wave 2 relational peer victimization was significantly smaller for girls than for boys. For self-reported peer victimization, Bboys = 0.05 (ns) and Bgirls = −0.19 (p < .05). For peer-nominated peer victimization, Bboys = 0.49 (p < .001) and Bgirls = 0.20 (p < .05). In general, girls who were physically victimized by peers in Wave 1 tended to experience less relational victimization at Wave 2, compared to boys.

References

- Adams RE, Bukowski WM. Peer victimization as a predictor of depression and body mass index in obese and non-obese adolescents. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:858–866. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. Sex differences in aggression in real-world settings: A meta-analytic review. Review of General Psychology. 2004;8:291–322. [Google Scholar]

- Card NA, Hodges EVE. Victimization within mutually antipathetic peer relationships. Social Development. 2007;16:479–496. [Google Scholar]

- Card NA, Hodges EV. Peer victimization among schoolchildren: Correlations, causes, consequences, and considerations in assessment and intervention. School Psychology Quartely. 2008;23:451–461. [Google Scholar]

- Card NA, Stucky BD, Sawalani GM, Little TD. Direct and indirect aggression during childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic review of gender differences, intercorrelations, and relations to maladjustment. Child Development. 2008;79:1185–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD, Dodge KA, Coppotelli H. Dimensions and types of social status: A cross-age perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1982;18:557–570. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell MA, Dukewich TL, Yosick R. Targeted peer victimization and the construction of positive and negative self-cognitions: Connections to depression in children. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39:1–15. doi: 10.1080/15374411003691776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Statistical methods for risk-outcome research: Being sensitive to longitudinal structure. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2009;5:71–96. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-060508-130357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craighead WE, Smucker MR, Craighead LW, Ilardi SS. Factor analysis of the Children's Depression Inventory in a community sample. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10:156–165. [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Bigbee MA. Relational and overt forms of peer victimization: A multi-informant approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:337–347. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Casas JF, Ku H. Physical and relational peer victimization in preschool. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:376–385. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Prinstein M. Applying depression-distortion hypotheses to the assessment of peer victimization in adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolsecent Psychology. 2004;33:325–335. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan RA, Hodges EVE, Perry DG. Preoccupied and avoidant coping during middle childhood. Child Development. 1996;67:1318–1328. [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Hammen CL. Handbook of depression. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Grills AE, Ollendick TH. Peer victimization, global self-worth, and anxiety in middle school children. Journal of clinical child and adolescent psychology. 2002;31:59–68. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3101_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawker DS, Boulton MJ. Twenty years' research on peer victimization and psychological maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2000;41:441–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EVE, Boivin M, Vitaro F, Bukowski WM. The power of friendship: Protection against an escalating cycle of peer victimization. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:94–101. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EVE, Perry DG. Personal and interpersonal antecedents and consequences of victimization by peers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:677–685. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs J, Hodges EVE, Salmivalli C. Long-term consequences of victimization by peers: A follow-up from adolescence to young adulthood. European Journal of Developmental Science. 2008;2:387–397. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog K, Sörbom D. LISREL, Version 8.53. Scientific Software International, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer BJ, Ladd GW. Peer victimization: Manifestations and relations to school adjustment in kindergarten. Journal of School Psychology. 1996;34:267–283. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Kochenderfer-Ladd B. Identifying victims of peer aggression from early to middle childhood: Analysis of cross-informant data for concordance, estimation of relational adjustment, prevalence of victimization, and characteristics of identified victims. Psychological Assessment. 2002;14:74–96. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.14.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Graf M. Pleasant activities and depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1973;41(2):261–268. doi: 10.1037/h0035142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. The two sexes: Growing up apart, coming together. Cambridge, MA: Belnap Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Marien WE, Bell DJ. Anxiety- and depression-related thoughts in children: Development and evaluation of a cognition measure. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:717–730. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3304_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML, Hilt LM. Emotion dysregulation as a mechanism linking peer victimization to internalizing symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:894–904. doi: 10.1037/a0015760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Bullying or peer abuse at school: Facts and interventions. Current Directions in Psychology Sciences. 1995;4:196–200. [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Boergers J, Vernberg EM. Overt and relational aggression in adolescents: Social-psychological functioning of aggression and victims. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 2001;30:477–489. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijntjes A, Kamphuis J, Prinzie P, Telch MJ. Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2010;34:244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigby K. Effects of peer victimization in schools and perceived social support on adolescent well-being. Journal of Adolescence. 2000;23:57–68. doi: 10.1006/jado.1999.0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross W. A national perspective of peer victimization: Characteristics of perpetrators, victims and intervention models. National Forum of Teacher Education Journal. 2006;16:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz D, Gorman AH, Nakamoto J, Toblin RL. Victimization in the peer group and children’s academic functioning. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2005;97:425–435. [Google Scholar]

- Storch EA, Masia-Warner C, Crisp H, Klein RG. Peer victimization and social anxiety in adolescence: A prospective study. Aggressive Behavior. 2005;31:437–452. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeting H, Young R, West P, Der G. Peer victimization and depression in early-mid adolescence: A longitudinal study. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 2006;76:577–594. doi: 10.1348/000709905X49890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Ormrod R. The effect of lifetime victimization on the mental health of children and adolescents. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62:13–27. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]