Abstract

Soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merril], one of the most important crop species in the world, is very susceptible to abiotic and biotic stress. Soybean plants have developed a variety of molecular mechanisms that help them survive stressful conditions. Hybrid proline-rich proteins (HyPRPs) constitute a family of cell-wall proteins with a variable N-terminal domain and conserved C-terminal domain that is phylogenetically related to non-specific lipid transfer proteins. Members of the HyPRP family are involved in basic cellular processes and their expression and activity are modulated by environmental factors. In this study, microarray analysis and real time RT-qPCR were used to identify putative HyPRP genes in the soybean genome and to assess their expression in different plant tissues. Some of the genes were also analyzed by time-course real time RT-qPCR in response to infection by Phakopsora pachyrhizi, the causal agent of Asian soybean rust disease. Our findings indicate that the time of induction of a defense pathway is crucial in triggering the soybean resistance response to P. pachyrhizi. This is the first study to identify the soybean HyPRP group B family and to analyze disease-responsive GmHyPRP during infection by P. pachyrhizi.

Keywords: fungal disease, HyPRP genes, Glycine max, real time RT-qPCR

Introduction

Soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merril], one of the most important and extensively cultivated crops in the world, is widely used for human and animal consumption because of the high protein and oil content of its seeds. Recently, soybean oil has emerged as a source of renewable fuel and its advantages over current food-based biofuels have been demonstrated (Hill et al., 2006). However, unfavorable field conditions may severely restrict the soybean yield, with one of the major concerns among Brazilian soybean producers being Asian soybean rust (ASR) disease. ASR, a severe disease caused by the fungus Phakopsora pachyrhizi, results in significant yield losses in soybean production and is rapidly spreading around the world (Pivonia et al., 2005; Carmona et al., 2005).

Understanding the mechanisms that regulate the expression of stress-related genes is a fundamental issue in plant biology and is essential for the genetic improvement of soybean. As part of a study aimed at improving the ability of soybean to survive unfavorable conditions, He et al. (2002) analyzed the expression of a soybean gene encoding a hybrid proline-rich protein (SbPRP). The distribution of SbPRP mRNA was organ-specific and its expression was modulated by ABA (abscisic acid), circadian rhythm, salt and drought stress; there was also significant up-regulation in response to viral infection and salicylic acid.

Hybrid proline-rich proteins (HyPRPs), a subset of proline-rich proteins (PRPs), are poorly glycosylated cell wall glycoproteins specific to seed plants. HyPRPs can be classified into two groups (A and B) based on the specific position of cysteine residues in the carboxy-terminal domain that is absent in other PRP sub-classes. More specifically, group A HyPRPs have 4–6 cysteine residues whereas the group B carboxy-terminal domain has eight cysteines in a conserved pattern. The latter group of HyPRPs usually contains a signal peptide followed by a central proline-rich domain (PRD) and a hydrophobic carboxy-terminal non-repetitive domain with the eight conserved cysteine motifs, known as the eight-cysteine motif domain (8CM) (Josè-Estanyol and Puigdomènech 2000; Josè-Estanyol et al., 2004; Battaglia et al., 2007).

Although huge progress has been made in understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying HyPRP action in several plants (Deutch and Winicov, 1995; Richards and Gardner, 1995; Goodwin et al., 1996; Josè-Estanyol and Puigdomènech, 1998; Wilkosz and Schläppi, 2000; Bubier and Schläppi, 2004; Zhang and Schläppi, 2007; Priyanka et al., 2010; Dvoráková et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2011), the roles of the soybean HyPRP gene family still remain largely unknown. The sequencing and assembly of the soybean genome (Schmutz et al., 2010) may provide new approaches for identifying protein-coding loci possibly involved in the ability of soybean to survive stressful conditions.

In this report, we describe the identification and annotation of the soybean group B HyPRP family and its expression in different tissues based on microarray analysis. A subtractive library enriched for genes induced in response to P. pachyrhizi was analyzed and genes closely related to SbPRP were investigated in time-course real time RT-qPCR experiments in response to ASR.

Material and Methods

Annotations

In order to identify all possible soybean group B HyPRP sequences the conserved eight-cysteine motif (8CM) carboxy-terminal domain of a previously reported SbPRP (He et al., 2002) was aligned (TBLASTN software) against the whole genome of Williams 82 soybean cultivar that is deposited in the Soybase and The Soybean Breeders Toolbox database. Homologous sequences with an e-value < 1e−06 were re-aligned against the soybean genome to recover the maximum number of related proteins. All positive matches were scanned for the 8CM carboxy-terminal domain in the SMART database (with default threshold). Sequences that shared the general organization of HyPRPs were aligned by their carboxy-terminal domain in order to evaluate the presence of the eight-cysteine motif; no gaps were inserted in the conserved 8CM core. Sequences that did not fit these criteria were excluded from the analysis.

Cluster analysis

Multiple sequence alignments of the 35 soybean HyPRPs were done with the entire carboxy-terminal domain sequences (8CM) using the MUSCLE tool implemented in MEGA v.5.0 (Tamura et al., 2011). Cluster analysis was done using two independent approaches: the neighbor-joining (NJ) method and the Bayesian method. The NJ method was done using MEGA v.5.0. The molecular distances of the aligned sequences were calculated according to the p-distance parameter, with gaps and missing data treated as pairwise deletions. Branch points were tested for significance by bootstrapping with 1000 replications. Bayesian analysis was done in MrBayes v.3.1.2 (Huelsenbeck and Ronquist, 2001; Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003) with the mixed amino acid substitution model + gamma + invariant sites. Default settings were maintained, with the exception of Nchains and Nswaps that were set to eight and two, respectively. Two independent runs of 2,000,000 generations each with two Metropolis-coupled Monte Carlo Markov chains (MCMCMC) were run in parallel, each one starting from a random tree. Markov chains were sampled for every 100 generations and the first 25% of the trees were discarded as burn-in. The remaining trees were used to compute the majority rule consensus tree (MrBayes command allcompat) and the posterior probability of clades and branch lengths. The unrooted phylogenetic tree was visualized and edited using the software FigTree v.1.3.1.

Data mining

The expression profiles of the identified soybean HyPRP sequences that responded to infection by ASR were determined by analyzing a subtractive library. Leaves from accession PI 561356 (a resistant soybean genotype) were removed 12 to 192 h after P. pachyrhizi inoculation and used to construct a cDNA library. This experiment was done as part of the Genosoja project, a Brazilian soybean genome consortium, and the results can be obtained from the LGE database (http://www.lge.ibi.unicamp.br/soja/) by members of the consortium.

The gene expression patterns in six tissues (root and root tip, nodule, leaves, green pods, flower and apical meristem) were determined by microarray analysis and the results are available from Soybean Atlas hosted at the University of Missouri. Gene expression was confirmed based on EST data obtained from NCBI.

Reverse transcription and real time RT-qPCR

Soybean total RNA was extracted from leaves, closed flowers, open flowers, pods, seeds, stems and roots using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and then treated with DNAse I (Promega), according to the manufacturer’s specifications. The first-strand cDNA synthesis reaction was done using approximately 2 μg of DNA-free RNA, M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase system™ (Invitrogen) and a 24-oligo dT anchored primer. Real time RT-qPCR was done in a StepOne Real-time Cycler (Applied Biosystems). The PCR-cycling conditions consisted of 5 min of initial denaturation at 94 °C, 40 cycles of 10 s denaturation at 94 °C, 15 s annealing at 60 °C and 15 s extension at 72 °C, with a final extension of 2 min at 40 °C. The reaction products were identified by melting curve analysis done over the range of 55–99 °C at the end of each PCR run, with a stepwise temperature increase of 0.1 °C every s. Each reaction mixture (25 μL) contained 12.5 μL of diluted DNA template, 1 X PCR buffer (Invitrogen), 2.4 mM MgCl2, 0.024 mM dNTP, 0.1 μM of each primer, 2.5 μL SYBR-Green (1:100,000; Molecular Probes Inc.) and 0.3 U of Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen). The first-strand cDNA-reaction product (1:100) was evaluated in relative expression analyses. Technical quadruplicates were used in all real time RT-qPCR experiments and the template was omitted from negative controls. The same approach was applied to RNA extracted from soybean leaves to measure HyPRP expression in response to ASR.

The PCR amplification reactions were done using gene specific primers (Glyma06g07070: Forward CACCCACTCCAACTCCATCT, Reverse GGCTTCGGAGGAGAAGGT; Glyma14g14220: Forward AAAAACTGTTCCTGCTGGCTT, Reverse TAAGGCAAACACGTGTTTACCTAG; Glyma04g06970: Forward GTCCTCCTCCTTCTCCTCCTT, Reverse GAGCGTCACAGGTACGTTCA; Glyma17g11940: Forward GAAGGTTTGGCTGATTTGGA, Reverse AATGAACCTAACATGATGGAAGC) and the products obtained were sequenced. Sequencing was done on an ABI PRISM 3100 Genetic Analyzer automatic sequencer (Applied Biosystems) in the ACTGene Laboratory (Centro de Biotecnologia, UFRGS, RS, Brazil) using forward and reverse primers, as described by the manufacturer. Primer pairs designed to amplify an F-box and metalloprotease gene sequences were used as internal controls to normalize the amount of cDNA template present in each sample (Libault et al., 2008). Relative changes in gene expression were described after comparative quantification of the target and reference gene amplified products using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). The relative expression levels in soybean plants under mock or fungal infection were analyzed using Student’s t-test with p < 0.05 indicating a significant difference (identified by an asterisk in the figures).

Bioassay for the analysis of HyPRPs expression during infection by ASR

The soybean plant reaction to ASR was evaluated by inoculating a field population of P. pachyrhizi spores initially collected from Brazilian soybean fields and maintained on a susceptible cultivar under greenhouse conditions until use. The experiment was done at Embrapa Soja (Londrina, PR, Brazil). Briefly, soybean plants were grown in a pot-based system and maintained in a greenhouse at 28 ±1 °C on a 16/8 h light/dark cycle at a light intensity of 22.5 μEm−2/s. The Embrapa-48 genotype was used as susceptible host as it develops a tan lesion after infection by ASR (van de Mortel et al., 2007), and the PI561356 genotype was used as a resistant host in which the resistance to soybean rust is mapped on linkage group G (Abdelnoor R.V., personal communication). Uredospores were harvested from infected leaves with sporulating uredia and diluted in distilled water with 0.05% Tween-20 to a final concentration of 3 × 105 spores/mL. The spore suspension was sprayed onto three plants per pot at the V2 to V3 stage of growth. The V2 stage consists of a fully developed trifoliolate leaf at a node above the unifoliolate nodes and V3 stage is characterized by three nodes on the main stem, with fully developed leaves beginning with the unifoliolate nodes (Fehr and Caviness, 1977).

Spores were omitted in mock inoculations. After the fungal or mock inoculations, water-misted bags were placed over all plantlets for one day to aid the infection process and to prevent the cross-contamination of mock-infected plants. One trifoliolate leaf from each plant was collected at 1, 12, 24, 48, 96 and 192 h after inoculation (hai), frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for RNA extraction. Three biological replicates from each genotype were analyzed for both treatments.

Results

Identification and microarray analysis of soybean HyPRP encoding genes

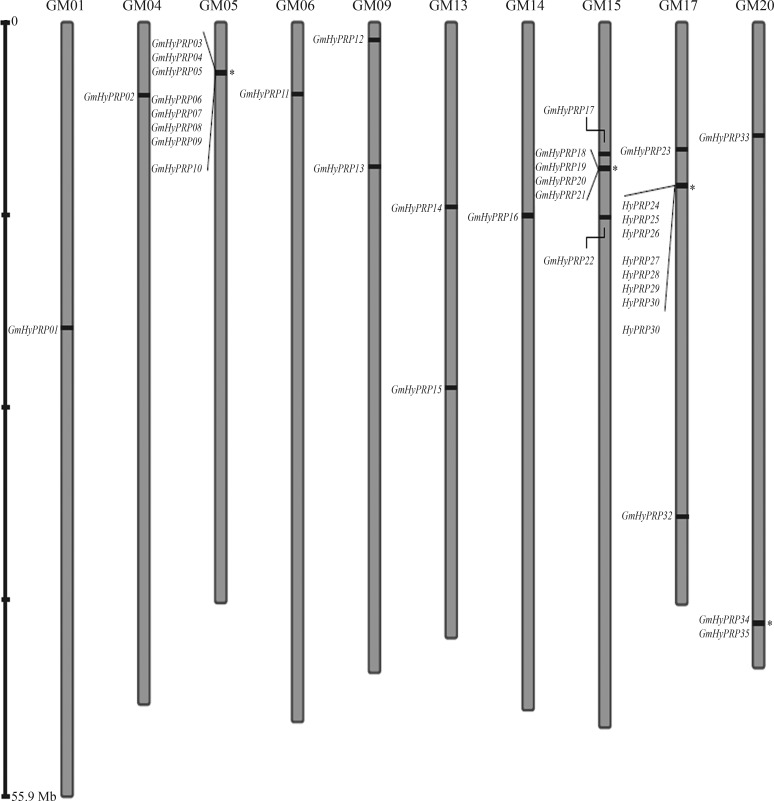

Annotation analysis based on the TBLASTN search of the 8CM carboxy-terminal domain of a previously reported SbPRP against Williams 82 soybean cultivar coding sequences in the Soybase and The Soybean Breeders Tool-box database identified 35 GmHyPRP-encoding genes in the soybean genome. The GmHyPRP genes were located in ten chromosomes, with protein sequences ranging in size from 120 to 385 amino acids. Chromosome 17 contained the highest number of GmHyPRP genes (10 out of 35), whereas only a single gene was detected in each of chromosomes 1, 4, 6 and 14. Figure 1 shows the relative locations of the genes on their respective chromosomes and genes located at loci close to each other are indicated as possible tandem duplications. A standardized nomenclature based on the gene order in the chromosomes was used for all GmHyPRP genes identified in this work. This same approach has recently been used by other researchers to facilitate the description of their findings (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Representation of the locations for GmHyPRP genes on each soybean chromosome. The asterisks indicate possible tandem duplicated genes. Gm indicates chromosome numbers.

Table 1.

Annotation of soybean HyPRP-encoding genes. Gene nomenclature was based on chromosomal order1.

| Accession number in Phytozome (gene) | Proposed name | Chromosome | CDS/ORF (bp) | Expression confirmed by EST (GenBank accession number) | Full-length protein confirmed by cDNA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glyma01g17820 | GmHyPRP01 | 1 | 387 | BQ273195.1 | + |

| Glyma04g06970 | GmHyPRP02 | 4 | 534 | EV274219.1 | + |

| Glyma05g04380 | GmHyPRP03 | 5 | 414 | EV263905.1 | + |

| Glyma05g04390 | GmHyPRP04 | 5 | 519 | AI496419.1 | + |

| BF595475.1 | |||||

| Glyma05g04400 | GmHyPRP05 | 5 | 411 | EV278968.1 | + |

| Glyma05g04430 | GmHyPRP06 | 5 | 405 | CA784637.1 | + |

| Glyma05g04440 | GmHyPRP07 | 5 | 411 | EV271119.1 | + |

| Glyma05g04450 | GmHyPRP08 | 5 | 540 | AW569247.1 | − |

| Glyma05g04460 | GmHyPRP09 | 5 | 381 | - | − |

| Glyma05g04490 | GmHyPRP10 | 5 | 396 | BG511695.1 | + |

| Glyma06g07070 | GmHyPRP11 | 6 | 666 | BI945945.1 | + |

| AW279308.1 | |||||

| Glyma09g01680 | GmHyPRP12 | 9 | 387 | FK021328.1 | + |

| Glyma09g10340 | GmHyPRP13 | 9 | 375 | FK001188.1 | + |

| Glyma13g11090 | GmHyPRP14 | 13 | 1155 | AW152930.1 | + |

| GR835813.1 | |||||

| BG649969.1 | |||||

| Glyma13g22940 | GmHyPRP15 | 13 | 684 | EV278617.1 | + |

| Glyma14g142202 | GmHyPRP16 | 14 | 381 | EV274235.1 | + |

| Glyma15g12600 | GmHyPRP17 | 15 | 384 | AW278280.1 | + |

| Glyma15g13740 | GmHyPRP18 | 15 | 360 | - | − |

| Glyma15g13750 | GmHyPRP19 | 15 | 360 | AW277674.1 | + |

| Glyma15g13760 | GmHyPRP20 | 15 | 387 | - | − |

| Glyma15g13770 | GmHyPRP21 | 15 | 390 | AW156395.1 | − |

| Glyma15g17570 | GmHyPRP22 | 15 | 420 | - | − |

| Glyma17g11940 | GmHyPRP23 | 17 | 573 | EV280964.1 | + |

| Glyma17g14840 | GmHyPRP24 | 17 | 408 | FK018257.1 | + |

| Glyma17g14850 | GmHyPRP25 | 17 | 513 | FK014996.1 | + |

| Glyma17g14860 | GmHyPRP26 | 17 | 411 | BQ453492.1 | + |

| Glyma17g14880 | GmHyPRP27 | 17 | 417 | BU083296.1 | + |

| Glyma17g14890 | GmHyPRP28 | 17 | 414 | BE347345.1 | + |

| Glyma17g14900 | GmHyPRP29 | 17 | 537 | AW398015.1 | + |

| Glyma17g14910 | GmHyPRP30 | 17 | 396 | EV268166.1 | + |

| Glyma17g14930 | GmHyPRP31 | 17 | 396 | EV271098.1 | + |

| Glyma17g32100 | GmHyPRP32 | 17 | 381 | BE347495.1 | + |

| Glyma20g062903 | GmHyPRP33 | 20 | 987 | BM886103.1 | + |

| BF070112.1 | |||||

| Glyma20g35070 | GmHyPRP34 | 20 | 369 | - | − |

| Glyma20g3508034 | GmHyPRP35 | 20 | 408/360 | - | − |

Soybean HyPRP-encoding gene annotation was based on Phytozome gene models. The expression data were obtained from the NCBI database.

The same approach was recently used by Le et al. (2011).

Previously reported as SbPRP (soybean proline-rich protein) by He et al. (2002).

Indicates a correction in the Phytozome gene models.

Based on the gene sequence Glyma20g35080 has two possible ORFs (with or without introns).

The previously reported SbPRP gene corresponds to the gene model Glyma14g14220 in the Williams 82 genome and, based on our criteria, was identified as GmHyPRP16. Only two gene models, corresponding to Glyma20g06290 (GmHyPRP33) and Glyma20g35080 (GmHyPRP35), were corrected manually and, based on the genomic sequence, one of them (Glyma20g35080) showed two possible open reading frames (ORFs), with or without the presence of an intron. However, a gene model without introns became more probable when all HyPRP cDNA sequence encoding proteins were analyzed, since none of the corresponding genes contained introns in their genomic sequences. Among the annotated genes, 29 had corresponding expressed sequence tags (ESTs) and 27 had their full length proteins confirmed, indicating that they are unlikely to be pseudogenes. Only for six genes were there no ESTs in either of the databases analyzed.

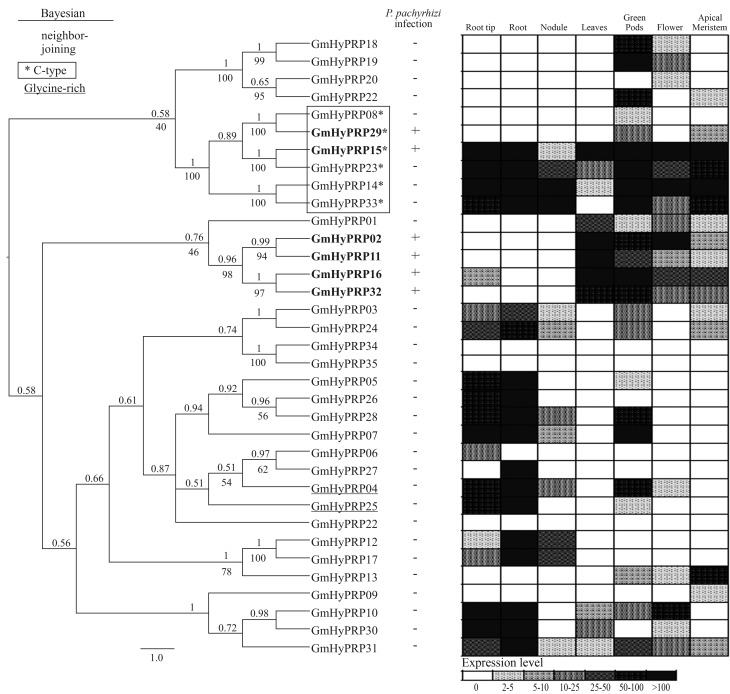

All soybean HyPRPs had an N-terminal secretion signal, except for GmHyPRP34 in which the peptide signal was replaced by a low complexity region. Since this protein was more related to a HyPRP than to any other class of cell wall proteins (data not shown), in the present study the corresponding gene was considered to be a member of the soybean HyPRP gene family. The sequences for GmHyPRP08, GmHyPRP14, GmHyPRP15, GmHyPRP29, GmHyPRP23 and GmHyPRP33 belong to the conserved-type (C-type) HyPRPs and those for GmHyPRP04 and GmHyPRP25 contain glycine-rich N-terminal domains. In the first group, the 8CM cluster analysis formed a stable branch in the tree, but this was not the case for the second group (Figure 2, left side; Supplementary Material Figure S1).

Figure 2.

Cluster analysis and expression patterns of soybean HyPRPs. Left - Bayesian cladogram of 35 soybean HyPRP proteins. The Bayesian analysis was done using Mr. Bayes v.3.1.2, after alignment of the conserved C-terminal domains of HyPRPs using Muscle. The unrooted cladogram was edited using FigTree v.1.3.1. Nodal support is given by the posteriori probability values above the branches. Numbers below the branches denote bootstrap values obtained for the same input data using neighbor-joining analysis in MEGA. The scale bar indicates the estimated number of amino acid substitutions per site. The genes were designated according to their locus ID in Phytozome. C-type proteins are shown in blue, glycine-rich N-terminal domains in red and genes responsive to ASR in bold. Middle - HyPRP expression [absence (−); presence (+)] in leaves from PI561356 (resistant genotype) infected with P. pachyrhizi (12–192 h). The data were obtained from subtractive library experiments available at www.lge.ibi.unicamp.br/soja/. Right - Microarray analysis of the expression profiles in root, root tip, nodule, leaves, green pods, flower and apical meristem of soybean plants. Data available at http://digbio.missouri.edu/soybean_atlas/.

Expression of the soybean GmHyPRP gene family was initially analyzed in response to ASR disease by mining a subtractive library in order to identify responsive genes. Six genes were up-regulated during infection by P. pachyrhizi (Figure 2, middle). GmHyPRP15 and GmHyPRP29 coded for soybean C-type HyPRPs while the other four genes (GmHyPRP02, GmHyPRP11, GmHyPRP16 and GmHyPRP32) formed a stable branch in which all members responded to the pathogen.

The expression profile of the 35 soybean genes identified as described above was assessed in six vegetative plant organs: root and root tip, nodule, leaves, green pods, flower and apical meristem (Figure 2, right side). Three genes (GmHyPRP22, GmHyPRP34 and GmHyPRP35) were not detected in any tissue. The other genes exhibited variable expression patterns. For example, GmHyPRP06, GmHyPRP08, GmHyPRP09, GmHyPRP20 and GmHyPRP27 were expressed in specific organs with differing transcript levels. A low, ubiquitous expression was observed for GmHyPRP30 while the opposite was true for GmHyPRP15, GmHyPRP23 and GmHyPRP14 (C-type), all of which exhibited a high, ubiquitous expression in all organs examined. The genes in the branch responsive to infection by P. pachyrhizi (GmHyPRP02, GmHyPRP11, GmHyPRP16 and GmHyPRP32) were almost exclusively highly expressed in leaves; GmHyPRP29 was not expressed in leaves whereas GmHyPRP15 had a more ubiquitous expression.

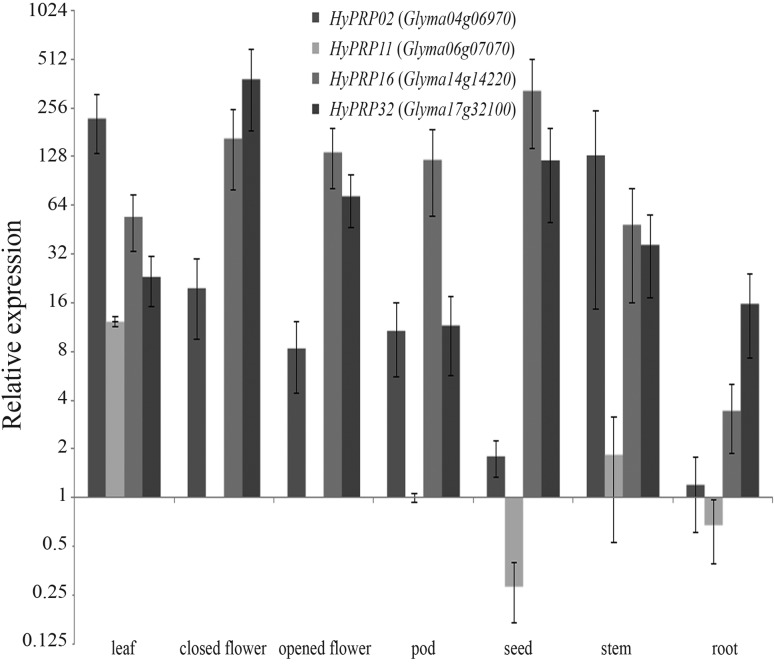

To confirm the array results for GmHyPRP16 and its paralogs, gene expression was measured by real time RT-qPCR in different soybean tissues (Figure 3). The four genes screened were detected in almost all tissues tested. GmHyPRP11 had a tissue-specific expression pattern and was not detected in flowers (either opened or closed).

Figure 3.

Expression profile of four soybean HyPRP-encoding genes in different plant tissues as assessed by real time RT-qPCR. The level of expression is shown relative to that of Glyma06g07070 in pods. The columns are the mean of three biological samples (pool of three plants each sample). Y bar indicates the standard error of the mean.

Time-course of HyPRP gene response to infection by P. pachyrhizi

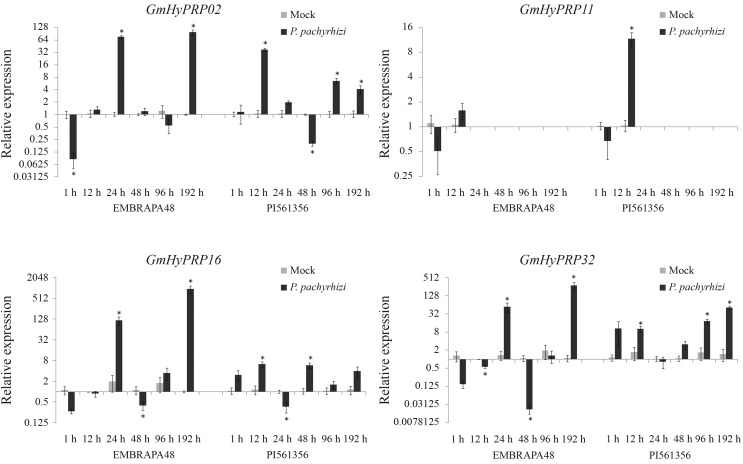

Since GmHyPRP16 and its paralogs were responsive in an ASR subtractive library and since all of them were expressed in leaves, real time RT-qPCR was used to analyze their transcript levels in soybean plants inoculated with P. pachyrhizi. A time-course experiment was used to examine the GmHyPRP02, GmHyPRP11, GmHyPRP16 and GmHyPRP32 expression pattern in leaves of the highly susceptible soybean genotype Embrapa-48 and in the more disease-resistant genotype PI561356 (Figure 4). In view of the difficulty in detecting GmHyPRP11 cDNA, this gene was analyzed at only two time points. Figure 4 shows that the susceptible soybean host HyPRP transcripts were significantly up-regulated at 24 h post-infection, with an additional increase, especially in SbPRP GmHyPRP16, at 192 h post-infection. In contrast, in the resistant soybean host, the expression of HyPRP transcripts was already strongly up-regulated 12 h after fungus inoculation and in all cases anticipated the gene response to infection by P. pachyrhizi. These plants exhibited less induction when compared to a susceptible genotype, with higher fold change occurring in GmHyPRP32 (192 h post-infection). The response to ASR also involved the expression of GmPR4 (Glyma19g43460) (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Expression profile of four soybean HyPRP-encoding genes in response to infection by Phakopsora pachyrhizi in the highly susceptible genotype Embrapa-48 and in the resistant genotype PI561356. Expression was assessed by real time RT-qPCR and is shown relative to the levels of F-box and metalloprotease. The columns are the mean of three biological samples (pool of three plants each sample). Y bar indicates the standard error of the mean. Asterisk (*) indicates p < 0.05 compared to mock.

Discussion

HyPRP organization and expression pattern

Soybean is a palaeotetraploid genome with two major duplication events dated to about 44 and 15 million years ago (Schlueter et al., 2004). Soybean was the first legume species sequenced (Schmutz et al., 2010) and its genome contains 950 megabases distributed in 20 chromosomes and > 46,000 protein-coding genes. During evolution polyploidy has had a deep effect on the soybean genome structure and organization and has contributed to the emergence of duplicated gene blocks that have been retained and remain active (Schmutz et al., 2010). Previous studies indicated that the genus Glycine has approximately twice as many chromosomes as its relatives (Doyle et al., 2004). Large scale analysis has shown that ∼75% of soybean genes are present in multiple copies. Diversification and gene loss, as well as chromosomal rearrangements, have modified the genomic structure over time (Schmutz et al., 2010). Zhu et al. (1994) estimated that 25% of duplicated genes have been lost since the last polyploidization event. EST analysis indicated that each soybean gene family consists of on average 3.1 members, a smaller number than would be expected if all copies from two duplication events were retained and expressed (Nelson and Shoemaker, 2006). However, the survival rates of duplicated gene classes vary, with some being more prone to retention than others. Gene families are retained and tend to grow if they have structural and/or functional features that allow diverse functions or undergo rapid subfunctionalization (Adams and Wendel, 2005; Lan et al., 2009).

To gain insight into the evolutionary dynamics of the soybean HyPRP family a phylogenetic analysis of their corresponding amino acid sequences was done using the entire carboxy-terminal domain (8CM) from Cucumis sativus (cucumber), Glycine max, Medicago truncatula and Prunus persica (peach) (Figure S2). Analysis of the 81 genes recovered from the databank revealed that soybean had the highest number of members, indicating that genome duplication events probably contributed to a greater number of genes than in the other species analyzed here.

We identified 35 soybean HyPRP-encoding genes that are widely distributed among plant chromosomes (1, 4, 5, 6, 9, 13, 14, 15, 17 and 20) and are arranged in tandem on chromosomes 5, 15, 17 and 20. This structural organization is characteristic of several cell wall glycoprotein-encoding genes in other species, such as Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa (rice) (Jose-Estanyol et al., 2004; Sampedro et al., 2005). HyPRP families with multiple copies have been described in other species (Dvorakova et al., 2007) and the large number of genes found in soybean agrees with the number expected for cell wall glycoproteins in plants, e.g., expansin-like A protein, that has 26 members in A. thaliana and 34 members in O. sativa (Sampedro et al., 2005).

Possibly the most striking feature of the 35 soybean HyPRPs was the complete absence of introns in their genetic structure. Jain et al. (2011) have demonstrated that intronless genes constitute a significant portion of the rice (19.9%) and Arabidopsis (21.7%) genomes and are associated with different cellular roles and gene ontology categories. Rapidly regulated genes may have lower intron densities and is crucial for rapid gene regulation during stress, cell proliferation, differentiation, or even during development. In this context, introns can delay appropriate regulatory responses, which may explain their absence from these sequences (Jeffares et al., 2008). Since HyPRPs are involved in a broad spectrum of plant responses to abiotic, biotic and developmental processes it is not surprising that a rapid adjustment in gene expression could help to overcome environmental challenges.

The N-terminal domain of known HyPRPs is highly variable in size and amino acid composition, probably because its repetitive nature allows it to undergo rearrangement (Fischer et al., 2002). In such cases, phylogenetic analyses based on a single domain rather than the full-length protein appear to be more reliable, despite the domains small size and poor sequence conservation (Brinkman and Leipe, 2001). As described here, the 8CM motif was examined to establish a relationship between soybean HyPRPs and their counterparts in other plants. This domain is widely distributed in seed plants and is shared by 2S-albumins, lipid transfer proteins (LTP), HyGRPs (hybrid glycine-rich proteins), amylase and trypsin inhibitors, and group B HyPRPs. The 8CM domain is involved in a variety of functions such as seed storage, enzymatic protection and inhibition, lipid transfer and cell wall structure (José-Estanyol et al., 2004). Since protein groups with distinct functions show high structural similarity with the 8CM domain it has been proposed that they share a common ancestral gene that accumulated modifications without altering the basic protein organization and acquired new functions over time (Henrissat et al., 1988). During plant evolution, the first HyPRP was possibly derived from an LTP that incorporated a proline-rich N-terminal domain by gene fusion or by the introduction of a repetitive element that became shorter and that was occasionally replaced by the glycine-rich domain (Dvorakova et al., 2007). Evolutionary history explains how sequences with N-terminal domains rich in glycine (GmHyPRP04 and GmHyPRP25) form a stable relationship with typical HyPRPs since unconventional N-terminal domains appear to occur in a repetitive and independent manner, indicating their polyphyletic origin (as shown by cluster analysis). Even a sequence without a signal peptide (GmHyPRP34) proved to be closer to HyPRPs than to other related proteins. This has never been described before and could be an artifact since the respective gene was not detected in the expression database, i.e., it could be a pseudogene.

C-type HyPRP proteins are a specific group of proteins with an N-terminal that is unusual in length and has a high content of hydrophobic residues. Soybean proteins that share these characteristics form a stable branch, as shown by cluster analysis. Even when the respective genes were analyzed together with those of other species they remained in the same branch (Figure S2). These proteins may be less divergent because they are ubiquitously expressed (Dvorakova et al., 2007), as was the case for GmHyPRP14, GmHyPRP15, GmHyPRP23 and GmHyPRP33 in this study. On the other hand, microarray experiments indicated that HyPRP08 and HyPRP29 had a distinct expression pattern. Interestingly, both of these proteins had the smallest N-terminal domain among soybean C-type HyPRPs (data not shown).

The overall gene expression in several soybean tissues (Figure 2 - right side, and Figure 3) revealed that in some cases duplicated members had overlapping specificities and similar activities. Other related paralogs diverged in their gene expression patterns. Modifications in the cis-regulatory elements of promoter regions could lead to transcriptional neofunctionalization or subfunctionalization (Haberer et al., 2004), which in turn could explain the similar or divergent responses in different plant tissues or even in response to the same stressor stimulus, e.g., HyPRP genes that maintain promoter recognition sites related to plant defense (GT1GMSCAM4 and WBOXATNPR1 identified upstream of the start of transcription; data not shown) and that are responsive to infection by P. pachyrhizi. Further studies involving promoter transformation to verify inducible expression patterns may clarify the involvement of duplicated genes in stress-related responses.

Response of soybean cultivars to infection by P. pachyrhizi

Phakopsora pachyrhizi induces biphasic global gene expression in response to ASR disease. The first peak of gene expression occurs during early infection and is a non-specific defense response similar to pathogen triggered immunity (PTI). The second peak of gene expression coincides with haustoria formation and effector secretion and is consistent with the activation of RPP2- and RPP3-mediated resistance (Mortel et al., 2007; Panthee et al., 2007; Schneider et al., 2011).

Twelve hours after fungal infection, when the early processes of apressorium formation and epidermal cell penetration occurred, the tolerant soybean genotype (PI561356) presented an up-regulation in HyPRP transcript levels whereas in the susceptible cultivar (Embrapa-48) no similar change was detected. The Embrapa-48 response occurred only 24 h after pathogen inoculation. Since the soybean HyPRP-encoding genes analyzed showed an expression peak in the first hours after fungal infection, we postulate that they might be involved in a non-specific defense response. The intense but late HyPRP expression in Embrapa-48 cultivar could be a decisive factor involved in plant susceptibility to pathogen attack since experiments based on global expression analysis suggest that the timing and the degree of induction of a defense pathway are pivotal in inducing the soybean resistance response to P. pachyrhizi (Mortel et al., 2007; Choi et al., 2008; Goellner et al., 2010; Schneider et al., 2011). A delayed attempt to block fungal invasion may not be as effective in stopping the infection as a less intense but early gene upregulation, such as observed in the resistant PI561356 genotype. Gene expression is reportedly faster and of greater magnitude in the incompatible interaction (Mortel et al., 2007; Panthee et al., 2007; Schneider et al., 2011).

Some cell wall proteins, e.g., extensins and proline-rich proteins (PRP), can respond promptly to pathogens, probably by enhancing physical barriers (Showalter, 1993; Schnabelrauch et al., 1996). The extensins are hydroxy-proline-rich glycoproteins (HRGPs) involved in cell wall self-organization during stress (Cannon et al., 2008) and it seems reasonable to suggest that GmHyPRPs may have an equivalent function through modification of the cell wall structure during ASR infection. HyPRPs were recently shown to be associated with cell-wall extension processes (Dvoráková et al., 2011). A subcellular localization experiment also indicated that at least HyPRP16 was secreted into the cell wall (Figure S3) where it possibly contributed to a defense mechanism against pathogen attack, perhaps by providing more than just a mechanical barrier.

Soria-Guerra et al. (2010) reported that HRGP transcript levels were upregulated in susceptible and resistant genotypes of Glycine tomentella during infection by P. pachyrhizi. Microarray experiments have demonstrated that several cell wall genes among those that encode for PRPs and HRGPs were upregulated in response to nematode invasion of the soybean root system (Khan et al., 2004). Even a role as one component in the defense signaling cascade cannot be ruled out since A. thaliana AZI1 (a HyPRP) has been shown to be involved in plant defense to ASR (Jung et al., 2009).

This work is the first to identify the soybean HyPRP group B family and to analyze disease-responsive GmHyPRP during infection by P. pachyrhizi. Our results indicate that the time of induction of a defense pathway is crucial to triggering the soybean resistance response to P. pachyrhizi, the causal agent of ASR. Future studies will improve our understanding of the relationship between the proteins described here and their role(s) in adaptation to biotic stress. Such information will provide a valuable genetic resource for engineering tolerance in soybean crops.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Brazilian Soybean Genome Consortium (Genosoja Project), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPQ) and BIOTECSUR. We thank Henrique Beck Biehl of the Centro de Microscopia Eletrônica (UFRGS) for his help with the confocal microscopy analysis and Silvia Nair Cordeiro Richter for her help with the picture editing.

Footnotes

Associate Editor: Everaldo Gonçalves de Barros

Supplementary Material

The following online material is available for this article:

- Figure S1 - Alignment of the conserved C-terminal domains of soybean HyPRPs using Muscle software.

- Figure S2 - Bayesian phylogenetic tree of 81 HyPRPs from soybean and three other plant species.

- Figure S3 - Subcellular localization of GmHyPRP16 in soybean root cells after dehydration.

This material is available as part of the online article from http://www.scielo.br/gmb.

References

- Adams KL, Wendel JF. Polyploidy and genome evolution in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2005;8:135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia M, Solorzano RM, Hernandez M, Cuellar-Ortiz S, Garcia-Gomez B, Marquez J, Covarrubias AA. Proline-rich cell wall proteins accumulate in growing regions and phloem tissue in response to water deficit in common bean seedlings. Planta. 2007;225:1121–1133. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0423-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkman FSL, Leipe DD. Phylogenetic analysis. In: Baxevanis AD, Ouelette BFF, editors. Bioinformatics: A Practical Guide to the Analysis of Genes and Proteins. Wiley; New York: 2001. pp. 323–358. [Google Scholar]

- Bubier J, Schläppi M. Cold induction of EARLI1, a putative Arabidopsis lipid transfer protein, is light and calcium dependent. Plant Cell Environ. 2004;27:929–936. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon MC, Terneus K, Hall Q, Tan L, Wang Y, Wegenhart BL, Chen L, Lamport DTA, Chen Y, Kieliszewski MJ. Self-assembly of the plant cell wall requires an extensin scaffold. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:2226–2231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711980105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona MA, Gally ME, Lopez SE. Asian soybean rust: Incidence, severity, and morphological characterization of Phakopsora pachyrhizi (Uredinia and Telia) in Argentina. Plant Dis. 2005;89:109. doi: 10.1094/PD-89-0109B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JJ, Alkharouf NW, Schneider KT, Matthews BF, Frederick RD. Expression patterns in soybean resistant to Phakopsora pachyrhizi reveal the importance of peroxidases and lipoxygenases. Funct Integr Genomic. 2008;8:341–359. doi: 10.1007/s10142-008-0080-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutch CE, Winicov I. Post-transcriptional regulation of a salt-inducible alfalfa gene encoding a putative chimeric proline-rich cell wall protein. Plant Mol Biol. 1995;27:411–418. doi: 10.1007/BF00020194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle JJ, Doyle JL, Rauscher JT, Brown AHD. Evolution of the perennial soybean polyploid complex (Glycine subgenus Glycine): A study of contrasts. Biol J Linn Soc. 2004;82:583–597. [Google Scholar]

- Dvoráková L, Cvrckova F, Fischer L. Analysis of the hybrid proline-rich protein families from seven plant species suggests rapid diversification of their sequences and expression patterns. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:e412. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvoráková L, Srba M, Opatrny Z, Fischer L. Hybrid proline-rich proteins: Novel players in plant cell elongation? Ann Bot. 2011;109:453–462. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcr278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr WR, Caviness CE. Stages on Soybean Development. 1977. Spec. Rep. No. 80. Coop. Ext. Serv., Agric. and Home Econ. Expn. Stn., Iowa State Univ., Ames, 21 pp.

- Fischer L, Lovas Á, Opatrny Z, Bánfalvi Z. Structure and expression of a hybrid proline-rich protein gene in the solanaceous species, Solanum brevidens, Solanum tuberosum, and Lycopersicum esculentum. J Plant Physiol. 2002;159:1271–1275. [Google Scholar]

- Goellner K, Loehrer M, Langenbach C, Conrath U, Koch E, Schaffrath U. Phakopsora pachyrhizi, the causal agent of Asian soybean rust. Mol Plant Pathol. 2010;11:169–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2009.00589.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin W, Pallas JA, Jenkins GI. Transcripts of a gene encoding a putative cell wall-plasma membrane linker protein are specifically cold-induced in Brassica napus. Plant Mol Biol. 1996;31:771–781. doi: 10.1007/BF00019465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberer G, Hindemitt T, Meyers BC, Mayer KF. Transcriptional similarities, dissimilarities, and conservation of cis-elements in duplicated genes of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2004;136:3009–3022. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.046466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He CY, Zhang JS, Chen SY. A soybean gene encoding a proline-rich protein is regulated by salicylic acid, an endogenous circadian rhythm and by various stresses. Theor Appl Genet. 2002;104:1125–1131. doi: 10.1007/s00122-001-0853-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henrissat B, Popineau Y, Kader JC. Hydrophobic-cluster analysis of plant protein sequences. A domain homology between storage and lipid-transfer proteins. Biochem J. 1988;255:901–905. doi: 10.1042/bj2550901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill J, Nelson E, Tilman D, Polasky S, Tiffany D. Environmental, economic, and energetic costs and benefits of biodiesel and ethanol biofuels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11206–11210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604600103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang G, Gong S, Xu W, Li P, Zhang D, Qin L, Li W, Li X. GhHyPRP4, a cotton gene encoding putative hybrid proline-rich protein, is preferentially expressed in leaves and involved in plant response to cold stress. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2011;43:519–527. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmr040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck JP, Ronquist F. MRBAYES: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:754–755. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain M, Khurana P, Tyagi AK, Khurana JP. Genome-wide analysis of intronless genes in rice and Arabidopsis. Funct Integr Genomic. 2011;8:69–78. doi: 10.1007/s10142-007-0052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffares DC, Penkett CJ, Bähler J. Rapidly regulated genes are intron poor. Trends Genet. 2008;24:375–378. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josè-Estanyol M, Puigdomènech P. Developmental and hormonal regulation of genes coding for proline-rich proteins in female inflorescences and kernels of maize. Plant Physiol. 1998;116:485–494. doi: 10.1104/pp.116.2.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josè-Estanyol M, Puigdomènech P. Plant cell wall glycoproteins and their genes. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2000;38:97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Josè-Estanyol M, Gomis-Ruth FX, Puigdomenech P. The eight-cysteine motif, a versatile structure in plant proteins. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2004;42:355–365. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josè-Estanyol M, Perez P, Puigdomenech P. Expression of the promoter of HyPRP, an embryo-specific gene from Zea mays in maize and tobacco transgenic plants. Gene. 2005;356:146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung HW, Tschaplinski TJ, Wang L, Glazebrook J, Greenberg JT. Priming in systemic plant immunity. Science. 2009;324:89–91. doi: 10.1126/science.1170025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan R, Alkharouf N, Beard H, Macdonald M, Chouikha I, Meyer S, Grefenstette J, Knap H, Matthews B. Microarray analysis of gene expression in soybean roots susceptible to the soybean cyst nematode two days post invasion. J Nematol. 2004;36:241–248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan T, Yang Z-L, Yang X, Liu Y-J, Wang X-R, Zeng Q-Y. Extensive functional diversification of the Populus glutathione S-transferase supergene family. Plant Cell Online. 2009;21:3749–3766. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.070219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le DT, Nishiyama R, Watanabe Y, Mochida K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K, Tran LS. Genome-wide survey and expression analysis of the plant-specific NAC transcription factor family in soybean during development and dehydration stress. DNA Res. 2011;4:263–276. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsr015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libault M, Thibivilliers S, Bilgin DD, Radwan O, Benitez M, Clough SJ, Stacey G. Identification of four soybean reference genes for gene expression normalization. Plant Gen. 2008;1:44–54. [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortel M, Recknor JC, Graham MA, Nettleton D, Dittman JD, Nelson RT, Godoy CV, Abdelnoor RV, Almeida AM, Baum TJ, et al. Distinct biphasic mRNA changes in response to Asian soybean rust infection. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2007;20:887–899. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-8-0887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson RT, Shoemaker R. Identification and analysis of gene families from the duplicated genome of soybean using EST sequences. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:204. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panthee DR, Yuan JS, Wright DL, Marois JJ, Mailhot D, Stewart Jr CN. Gene expression analysis in soybean in response to the causal agent of Asian soybean rust (Phakopsora pachyrhizi Sydow) in an early growth stage. Funct Integr Genomic. 2007;7:291–301. doi: 10.1007/s10142-007-0045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pivonia S, Yang XB, Pan Z. Assessment of epidemic potential of soybean rust in the United States. Plant Dis. 2005;89:678–682. doi: 10.1094/PD-89-0678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priyanka B, Sekhar K, Reddy VD, Rao KV. Expression of pigeonpea hybrid-proline-rich protein encoding gene (CcHyPRP) in yeast and Arabidopsis affords multiple abiotic stress tolerance. Plant Biotechnol J. 2010;8:76–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2009.00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards KD, Gardner RC. pEARLI1 (Accession No. L43080): An Arabidopsis member of a conserved gene family (PGR95–099) Plant Physiol. 1995;109:1497. [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampedro J, Lee Y, Carey RE, DePamphilis C, Cosgrove DJ. Use of genomic history to improve phylogeny and understanding of births and deaths in a gene family. Plant J. 2005;44:409–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlueter JA, Dixon P, Granger C, Grant D, Clark L, Doyle JJ, Shoemaker RC. Mining EST databases to resolve evolutionary events in major crop species. Genome. 2004;47:868–876. doi: 10.1139/g04-047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmutz J, Cannon SB, Schlueter J, Ma J, Mitros T, Nelson W, Hyten DL, Song Q, Thelen JJ, Cheng J, et al. Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature. 2010;463:178–183. doi: 10.1038/nature08670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnabelrauch LS, Kieliszewski M, Upham BL, Alizedeh H, Lamport DT. Isolation of pl 4.6 extensin peroxidase from tomato cell suspension cultures and identification of Val-Tyr-Lys as putative intermolecular cross-link site. Plant J. 1996;9:477–489. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1996.09040477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider KT, van de Mortel M, Bancroft TJ, Braun E, Nettleton D, Nelson RT, Frederick RD, Baum TJ, Graham MA, Whitham SA. Biphasic gene expression changes elicited by Phakopsora pachyrhizi in soybean correlate with fungal penetration and haustoria formation. Plant Physiol. 2011;157:355–371. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.181149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Showalter AM. Structure and function of plant cell wall proteins. Plant Cell. 1993;5:9–23. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soria-Guerra RE, Rosales-Mendoza S, Chang S, Haudenshield JS, Padmanaban A, Rodrigues-Zas S, Hartman GL, Ghabrial S, Korban SS. Transcriptome analysis of resistant and susceptible genotypes of Glycine tomentella during Phakopsora pachyrhizi infection reveals novel rust resistance genes. Theor Appl Genet. 2010;40:1432–2242. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1258-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Mortel M, Recknor JC, Graham MA, Nettleton D, Dittman JD, Nelson RT, Godoy CV, Abdelnoor RV, Almeida AM, Baum TJ, et al. Distinct biphasic mRNA changes in response to Asian soybean rust infection. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2007;20:887–899. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-8-0887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkosz R, Schläppi M. A gene expression screen identifies EARLI1 as a novel vernalization-responsive gene in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol. 2000;44:777–787. doi: 10.1023/a:1026536724779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D, Huang X, Xu ZQ, Schläppi M. The HyPRP gene EARLI1 has an auxiliary role for germinability and early seedling development under low temperature and salt stress conditions in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2011;234:565–577. doi: 10.1007/s00425-011-1425-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Schläppi M. Cold responsive EARLI1 type HyPRPs improve freezing survival of yeast cells and form higher order complexes in plants. Planta. 2007;227:233–243. doi: 10.1007/s00425-007-0611-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu T, Schupp JM, Oliphant A, Keim P. Hypomethylated sequences: Characterization of the duplicated soybean genome. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;244:638–645. doi: 10.1007/BF00282754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Internet Resources

- Soybase and The Soybean Breeders Toolbox database, http://soybase.org/ (accessed in July 6, 2011).

- FigTree v.1.3.1, http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/ (accessed in July 6, 2011).

- Genosoja project, LGE database, http://www.lge.ibi.unicamp.br/soja/ (accessed in July 6, 2011).

- Soybean gene expression patterns in tissues in Soybean Atlas, http://digbio.missouri.edu/soybean_atlas/ (accessed in July 6, 2011).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

- Figure S1 - Alignment of the conserved C-terminal domains of soybean HyPRPs using Muscle software.

- Figure S2 - Bayesian phylogenetic tree of 81 HyPRPs from soybean and three other plant species.

- Figure S3 - Subcellular localization of GmHyPRP16 in soybean root cells after dehydration.