Abstract

Evidence-based programs have been shown to improve functioning and mental health outcomes, especially for vulnerable populations. However, these populations face numerous barriers to accessing care including lack of resources and stigma surrounding mental health issues. In order to improve mental health outcomes and reduce health disparities, it is essential to identify methods for reaching such populations with unmet need. A promising strategy for reducing barriers and improving access to care is Community Partnered Participatory Research (CPPR). Given the power of this methodology to transform the impact of research in resource-poor communities, we developed an NIMH-funded Center, the Partnered Research Center for Quality Care, to support partnerships in developing, implementing, and evaluating mental health services research and programs. Guided by a CPPR framework, center investigators, both community and academic, collaborated in all phases of research with the goal of establishing trust, building capacity, increasing buy-in, and improving the sustainability of interventions and programs. They engaged in two-way capacity-building, which afforded the opportunity for practical problems to be raised and innovative solutions to be developed. This article discusses the development and design of the Partnered Research Center for Quality Care and provides examples of partnerships that have been formed and the work that has been conducted as a result.

Keywords: Community Based Participatory Research, Mental Health, Community-academic Partnership

Introduction

Community Partnered Participatory Research (CPPR) is a form of Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) that engages community and academic investigators in all phases of research. It has the potential to transform the way that research is designed, conducted, and disseminated and the power to build capacity in resource-poor communities and among community and academic investigators. To stabilize and enable this form of research, groups conducting CBPR-related studies over time have developed sustainable and effective infrastructures based in academic and community partnerships.1–3 In 2003, we developed an infrastructure in Los Angeles to support development of a CPPR-based research environment to address health disparities across several major chronic health conditions.2 Through community engagement, that infrastructure supported pilot studies including the Witness for Wellness initiative to address depression in South Los Angeles,4–8 pilots that expanded application of evidence-based approaches to child exposure to community violence from school-based programs to faith-based organizations,9 as well as to describe existing networks of community agencies that provide mental health and substance abuse services.10 In addition to this work in Los Angeles, we collaborated with other centers nationally to develop the approach more generally in mental health11 and supported a community-academic collaborative dedicated to mental health recovery in New Orleans following the 2005 Gulf storms and floods.12 Based on those experiences in developing infrastructures to support application of CPPR across health conditions, and in pilot programs to apply CPPR to mental health services research and services delivery, we proposed and were funded by the National Institute for Mental Health (NIMH) to develop a Partnered Research Center for Quality Care, as partnered infrastructure to support research on mental health services and outcomes under a CPPR framework. This article describes the goals, design and activities of that infrastructure and how the center continues to evolve through applying the principles and structure of CPPR to mental health research.

Nationally representative studies have documented a substantial gap between the quality of mental health care delivered and that recommended in national guidelines.13,14 The quality gap is exacerbated by access problems for underserved minority groups and vulnerable populations such as children, the elderly, and persons diagnosed with serious mental illness. For persons in such groups, factors including limited financial access and living in resource-poor communities are commonly made worse by high levels of unmet need coupled with other barriers to care, including language and social stigma associated with mental illness or help-seeking.15 For example, some persons with serious mental illness may avoid seeking services because of social stigma, negative prior experiences, or fear of involuntary treatment.16–18 In addition, rates of access to evidence-based care for common disorders such as depressive disorders are low in community samples (20%–30%); rates of unmet need are especially high among underserved groups such as African Americans and Latinos.19–22 Given these gaps and the demonstrated health benefits and improvement in functional status afforded by participating in evidence-based programs for mental disorders in vulnerable populations,23–25 it is imperative to determine how to best engage these populations in understanding and realizing the potential benefits from such programs. The importance and timeliness of doing so is enhanced by passage of federal parity and health reform legislation that have potential to improve access and equity of the distribution of mental health services.

Community Based Participatory Research is a promising approach to engaging vulnerable populations to address health disparities1,26–29 and to help individuals understand their options to receive services and improve mental health outcomes under new federal policies. By shifting research toward priorities of community members and leaders and promoting active community participation in research and program development, CBPR builds capacity in the community.3 One form of CBPR is Community Partnered Participatory Research (CPPR),30–32 a manualized approach that supports community and academic co-leadership in design, implementation, evaluation, and dissemination of research, and in building capacity of the partnership and community agencies to improve health of the community over time through joint planning and research.30 Under this approach, academic partners are considered part of the working community and community members are considered active members in the research process. Together they form a council of stakeholders that supports and guides an initiative and oversees working groups that develop and implement action plans and evaluations. The council regularly reviews and reevaluates the direction of the research to ensure that core values, which include trust, respect, and equality, are upheld and to ensure productivity and mutual benefit. Community engagement activities reinforce these values and enhance motivation of all participants to improve communication and power sharing, through leveling the playing field. Activities include conferences with partnered presentations, skits demonstrating real world situations, and participation in community events and festivals. Initiatives are guided through stages, including Vision (development of mission, goals); Valley (implementation and evaluation of action plans); and Victory (products, dissemination and formulation of next steps and lessons learned). The model promotes the implementation of evidence-based interventions while attending to social and cultural diversity of local communities, and thus is a useful framework for integration of intervention and services research within an overall community-based participatory research approach.31,33 Motivated by the promise of this approach, the demonstrated efficacy of the model in producing immediate results from pilot studies, and recognition that an infrastructure to support this model would lead to further innovative and efficient applications of this research paradigm, we developed the Partnered Research Center for Quality Care.

Methods

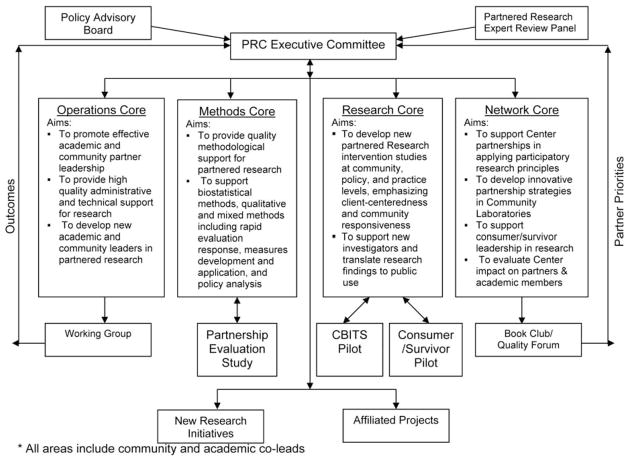

The overall aim of the Partnered Research Center for Quality Care is to study how to improve mental health care quality and outcomes through authentic community-academic partnered research that responds to community priorities and builds community capacity using principles and strategies of community engagement. The framework guiding our center is illustrated in Figure 1. At the top of the figure are principles of authentic partnerships under the CPPR Model30,31 used to initiate a community engagement process and to develop a network among key stakeholders. Also at the top of the figure, we highlight policy and research inputs into this process as they inform issue selection, and may affect the availability of resources for the work. The network is supported in identifying issues that are good fits of academic and partner priorities, resources and opportunities. The engaged network is supported by academic and community resources and capacities, in discovering or developing interventions at policy, practice, or local community levels that may plausibly improve quality of care in communities. Academic and community resources also result in partnered intervention implementation and evaluation, providing data on intervention outcomes for relevant stakeholders, including policymakers, networks, providers, consumers/survivors, and the broader community. Further, the lessons learned and capacities developed through the work increase capacity for partnered research and yield a library of priorities addressed, strategies developed, and a supported, vibrant partnership. This framework integrates prior models for improving access to quality care, community-based intervention research, and partnered participatory research.31,34–37

Fig 1.

Framework for partnered research center for quality care

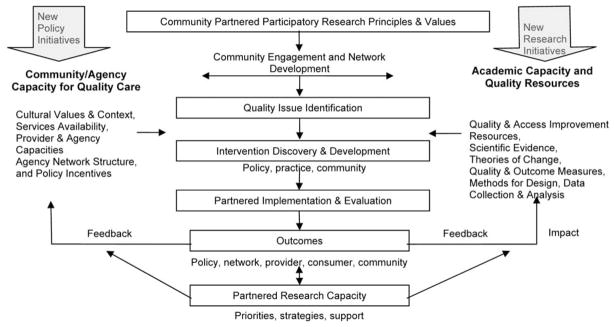

To support this capacity-building enterprise, the executive committee, comprising core leaders, meets once a month to discuss center progress, potential new directions, and allocation of resources to advance center work. Through this monthly meeting, new ideas and priorities from each core and those generated through center activities such as book clubs or conferences feed back to the executive committee and decisions are made by majority vote (Figure 2). The executive committee also receives feedback, to assure direction and impact, from the policy advisory board, which consists of academic and community institutional and policy leaders. At the suggestion of a key community partner, and with consensus from the executive committee, it was decided that the policy advisory board’s role be modified to allow for a bidirectional information exchange rather than a unidirectional provision of information, which characterizes a traditional advisory board meeting. Under the revised plan, the center will not only share accomplishments and obtain feedback, but also provide feedback to advisory board members through a knowledge exchange forum. The role of the partnered research expert review panel, which includes both expert scientists and their expert community partners, is to support rigor in application of scientific and community perspectives on partnered research, as well as to support application of this approach to research development across other programs, in a two-way exchange of approaches, strategies, findings, and programs.

Fig 2.

Partnered research center for quality care structure*

As seen in Figure 2, our center is composed of four cores, each structured to assure that the core values of CPPR are upheld, yet each serving a unique function designed to provide resources and facilitate the flow of information and relationships among all partners. Reflecting CPPR principles, each core consists of community and academic co-leads. The operations core provides administrative and technical support to partnered projects and to investigators who are developing projects under a CPPR framework. Through this core, and with approval from the executive committee, support is provided for the formation of working groups, which serve to build partners’ knowledge base in a new research area and have the potential to develop into independent projects. The methods core provides statistical consultation from experts in the field on design, measures, and analyses issues. This core also oversees the Partnership Evaluation Study, which replaced the original networking pilot when the executive committee voted to reallocate resources in support of this project that aims to describe center partnerships and make recommendations for more effective future partnerships. The principal research core provides guidance to junior investigators and to developing projects, such as the pilot assessing the sustainability of Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools and the Peer Intervention to Improve Treatment Decision-Making. Finally, the network core provides support for establishing and maintaining healthy partnerships and effectively engaging community partners and consumers/survivors. This core serves a convening function and sponsors regular book club meetings and a yearly community quality forum to generate new research initiatives informed by partner priorities.

Despite having a distinct role in the center, each core aims to promote research that is conducted in partnership in order to address priority areas in mental health and there is much cross-collaboration among the cores. For instance, the community quality forum obtains broad academic and community input to jump-start new partnered initiatives, which are supported in their development through the methods core for technical matters and network core for partnership development. Being responsive to partner priorities necessitates a flexible center structure whereby activities may lead to unanticipated activities, which then may reshape the existing center structure. For instance, the network core-sponsored book club, which provides partners the opportunity to come together on a bimonthly basis and have an open discussion on readings selected by community and academic partners, led to the unanticipated activity of expanding a small book club into a community outreach event around resilience and recovery. This in turn led to the reshaping of the center structure via the formation of a consumer/survivor board and greater consumer/survivor participation in the executive committee. These unanticipated activities are expected to occur due to the nature of CPPR, but they are an unknown at the outset and become part of the center structure with approval from the executive committee.

The aims of the four center cores are aligned with the core values of CPPR: respect for diversity, openness, equality, empowerment, and asset-based approach. Respect for diversity highlights the importance of respecting and honoring that both academics and community members have skills to contribute and experiences that can help shape the research. Openness acknowledges the fact that there will be questions or disagreements that arise through the course of research and the best way to address these is by being open to listening to or expressing new perspectives, asking for clarification, and open to thinking outside of the box. Equality emphasizes that community and academic members of the group must share equally in decision-making power in all phases of research. Empowerment reminds us that all groups have power and that this power can be redirected to bring forth the strengths of each group. This is a two-way process; community members can be empowered through trainings prior to group meetings and academics can be empowered through inclusion in community events. One example of such a two-way process is the network core-sponsored book club, which is conducted informally as compared to a traditional journal club. For instance, one of our book clubs consisted of a collection of readings ranging from poetry to peer-reviewed journal articles and allotted time for sharing musical selections pertinent to the theme that each participant contributed. Partners discussed how the music related to the theme and, at the same meeting, discussed rigorous scientific methods that might not be thought feasible for discussion in such diverse groups. Through such activities, community leaders for methods work groups are developed, thus empowering community partners, and academic members are exposed to expressions of culture, thus empowering academic partners. Finally, it is important to have an asset-based approach that recognizes the strengths of both community and academic members in order to build capacity and remind everyone that each and every member has something to bring to the table. Table 1 lists several of the key principles of community engagement that are central to the CPPR model and provides examples of how the center structure facilitates the application of those principles, how these principles have led to new ideas, and how these ideas have in turn led to activities not initially planned.

Table 1.

Examples of community engagement (CE) principles as applied to center work

| CE principle | CE principle in action | Idea generated | Resulting activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co-planning of activities | Each center component is led by community and academic co-PIs with equal decision- making power | Modify traditional advisory board meeting to allow for reciprocal sharing of ideas and accomplishments | Knowledge exchange forum |

| Regular communication | Monthly core conference calls coordinated by a research assistant assigned to each core to facilitate communication | Hold unstructured meetings to allow for free discussion of current topics to stimulate new ideas and encourage discussion among partners in an informal setting | Bimonthly book club |

| Transparency | Partnered executive committee discussion of new ideas | Revise an already approved pilot project to allow for increased consumer/survivor involvement. | Draft proposal and circulate to center members allowing the opportunity to ask questions and give feedback prior to changing protocol |

| Funding | Center administrator circulates funding opportunities to center listserv | Discuss opportunities at executive meeting | Grant proposal review meetings for community and academic investigators to provide feedback prior to submitting to the funding agency |

| Commitment to productivity, impact, & accountability | Cores that meet regularly and bring forth ideas to the executive committee | Assess the impact of the declining economy on the mental health of the community | Partnered design, implementation and analysis of a survey administered at a community festival. Disseminate findings via scientific journals and community newsletters. |

| Understand priorities & histories | Community and academic co-PIs for each core and project | Increase consumer/survivor involvement to heighten awareness of recovery focus | Develop a consumer/survivor board |

| Recognition of community input | Include community members on all cores, committees and working groups | Support community member who has an idea for a research activity, but lacks resources to implement it | Funds allocated for a community scholar |

| Institutional recognition | Invite institutional and funding agency representatives to join executive meetings | Give community partners the opportunity to attend scientific meetings | Community and academic partners present together on a panel at Academy Health |

Process

To successfully engage in partnered research and build and maintain strong partnerships, the Partnered Research Center actively engages in CPPR methods in all activities as described below.

Executive Meeting Structure

The center leadership and key staff convenes once a month for our executive committee meeting, alternating our meeting site between an academic and community partner location, with the option of participating via phone. Most meetings begin with a community engagement activity, which sets a relaxed tone and allows partners the opportunity to interact informally before delving into the agenda. Meetings are set on a recurring schedule to ensure that center members have the block of time consistently available and reminders are circulated 7–10 days in advance of the meeting date along with the prior meeting’s minutes and a proposed agenda. Center members are invited to revise the agenda to ensure that partner priorities are discussed. Typical agenda items include: status updates from each core, planned grant submissions and how to allocate support for these, planned products such as peer reviewed articles or website updates, development of new pilot projects, working groups, or research fellows, and proposed new project affiliations or consultants to invite to center events or from whom to obtain expert advice on particular issues. The meeting is co-chaired by an academic and community member and all decisions are voted on by the group.

Decision Making

Decisions are made by majority vote with community representing at least half of the vote. Major decision points are included on executive meeting agendas, discussed, and then voted on by the group. If there is not an equal distribution of community and academic partners present, suggestions can be made at the meeting and then circulated via email. As trust has developed at our center, we are now able to reach decisions via phone or email follow-up.

Budget

Decisions made often have budget implications. The center budget was prepared for the entire five-year period of the current center at the time of funding and is resubmitted annually at the time of progress report submission. It is reviewed regularly and resources are reallocated with consensus of center members, within limits set in place by the National Institutes of Health. Such decisions are almost exclusively made at the executive committee meeting to ensure transparency and full disclosure. If urgent rebudgeting decisions need to be made, phone or in-persons meetings can be quickly scheduled. Having a center infrastructure allows for budget changes to be implemented without negatively impacting the work of the overall center.

Working Groups

The formation of working groups is discussed and voted on at executive meetings. Ideas for working groups develop often out of sideline conversations among center partners or investigators on affiliated projects. Ideas generated are then brought back to the executive committee and the working group structure as well as suggested participants are discussed. The committee also votes on how resources should be allocated to support the work group, which often includes the support of a research assistant to conduct literature searches, coordinate meetings, and follow up on action items. In line with center principles, working groups are co-led by a community and academic investigator, products are created for distribution to a community and academic audience, and the group often leads to future proposals or independent projects.

Affiliated Projects

Projects with aims consistent to those of the center can request affiliation. By affiliating with the center, projects will have access to resources such as staff support, consultation from center leaders, or in some cases financial support. In turn, the center gains from expanding its scope and supporting projects that advance the center mission.

Community Scholar

The decision to fund a community scholar was made by the center in order to nurture the development of community members so they may fill a role similar to that of a junior investigator. Community scholars are assigned a mentor for their project, are supported in identifying a research goal, and receive training on effective implementation. The project aims must fit with the overall center mission.

Memorandum of Understanding

The center developed a formal agreement, or memorandum of understanding (MOU), to outline center principles, policies, and define the role of affiliated projects at the center. The document was developed and circulated to all center members for review. All feedback was incorporated and the revised document was discussed and signed at one of the executive committee meetings. This article describes many of the components formalized by the MOU and a few outcomes that have resulted from engaging in this work.

Results

In the early phases of the center we worked across the partnership to select and propose three R01s concerning the effects of policy, practice, and community-level interventions on quality of care. All three were developed with extensive partner and expert consultant input and each was funded and now are main affiliated studies within the center. The studies are: 1) an evaluation of the impact of the Medicare Remodernization Act (MRA) on elderly use of anti-anxiety agents; 2) an evaluation of the impact in Los Angeles County of the California Mental Health Services Act; and 3) Community Partners in Care, which evolved out of the Witness for Wellness Program to address the problem of depression in South Los Angeles. Other center work focused on a set of problems of mutual interest include: 1) depression and anxiety disorders in the general community, but especially underserved communities of color; 2) children exposed to violence and school based interventions; 3) common childhood disorders such as attention deficit disorder and depression; 4) severe and persistent mental illness, particularly schizophrenia; 5) communities exposed to disasters, especially New Orleans post-Katrina and long-term recovery. Table 2 provides a summary of selected active projects currently being conducted either through or in affiliation with the Partnered Research Center for Quality Care.

Table 2.

Selection of Partnered Research Center for Quality Care projects

| Project | Selected partners | Aims |

|---|---|---|

| Community partners in care | Behavioral Health Services, Healthy African American Families (HAAF), HOPICS, Los Angeles Urban League, NAMI Urban Los Angeles, Queenscare, RAND, St. John’s Well Child & Family Center | Group-level, randomized comparison trial of a community-engagement, network-building intervention and a low-intensity dissemination approach, each designed to promote adoption of key components of two established, evidence-based quality improvement (QI) programs for depression. |

| REACH-NOLA: -Mental health infrastructure & training | Holy Cross Neighborhood Association, Common Ground Health Clinic, St. Thomas Community Health Center, University of Washington, REACH NOLA, Tulane Community Health Center at Covenant House, Kaiser Permanente, St. Anna’s Episcopal Church, UCLA, RAND, Tulane University School of Medicine, Trinity Counseling and Training Center | A collaboration of many local and national nonprofit organizations, public agencies, and academic institutions that seeks to address depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). |

| CBITS | Los Angeles Unified School District, Madison School District, Mercy Family Center, Queenscare, RAND, UCLA, University of California San Diego, University of Southern California | -To evaluate, in a randomized controlled trial, a brief group intervention to address PTSD and depressive symptoms in students-To partner with a faith-based community to disseminate CBITS in parochial schools- To study implementation feasibility and sustainability in schools across three communities: Los Angeles, New Orleans, and Madison-To study a quality improvement approach to improve implementation of CBITS in the schools compared to implementation as usual |

| Adoption work | CASE, TIES for Adoption, UCLA | To develop a manualized intervention for children adopted from foster care aimed at decreasing risk for substance abuse and increasing family and child adjustment. |

| Decision Aid | CalMEND, UCLA | -To pilot-test a clinician decision support tool for adults receiving medication treatment for serious mental illness in Medicaid-funded outpatient specialty mental health programs. |

| Resilience workgroup | DHHS, HAAF, LA Department of Public Health, LAUSD, NIMH, NIOSH, RAND, Red Cross, SAMHSA/CMHS, Southwestern Medical Center, University of Cincinnati, University of Pennsylvania, UCLA, USC, VA | To define community resilience and identify ways to assess communities’ assets and strengths, critical measures, ways of tracking resilience, and to identify successful intervention models. |

| Mental Health Services Act Study | LA Department of Mental Health (LA DMH), UCLA, USC, Veterans Affairs | To document implementation of the MHSA in LA County and understand how an influx of funds into new specialized public mental health programs affects clients and providers in those programs and clients and providers in non-MHSA programs. |

| Stigma reduction | LA DMH, UCLA | To combat stigma and discrimination by conducting oral history interviews and identifying archival documents from numerous sources. |

New priorities are emerging as the center progresses and as they do, working groups are formed to bring together key stakeholders in discussing these priorities and formulating an action plan. For example, a new focus on community resilience as our communities and the nation face the impact of a declining economy as well as tragic events such as major disasters and community violence led to the creation of a working group to develop conceptual frameworks or models and interventions to promote resilient communities. This group successfully convened over 20 stakeholders from local, state, and federal agencies representing Los Angeles Unified School District, RAND Health, UCLA, Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, the Veterans Administration Greater Los Angeles Health System, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Mental Health, the Department of Health and Human Services, the American Red Cross, Tulane University, the University of Southern California, the University of Pennsylvania, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the HHS Department of Preparedness and Response, and Healthy African American Families. As a result of this working group, the center has a new affiliated pilot project in Los Angeles County being conducted by the Los Angles Department of Pubic Health, Emergency Network Los Angeles, UCLA, and RAND to build community capacity and response around emergency preparedness and disaster recovery issues. Other examples of new priority areas include health information technology, the impact of health reform, and biomarkers, a topic of critical importance that has been difficult to address due to historical distrust of research in this field.38 Working groups on each of these topics are currently being formed and will be active throughout the 2011 calendar year.

A key theme of these working groups is the importance of policy for sustainability. In acknowledgment of this and of recent potentially transformative policy changes for mental health services, the center has been actively exploring the salience of a CPPR approach for partnering with policy partners on topics ranging from medical home models for mental health with Los Angeles County and the State Department of Mental Health to the impact of parity legislation with managed care partners to new partnerships around community engagement in preparedness and disasters. Policy partners range from community members to local and national partners. For example, the center initiated a partnership with a staff member from the White House Office of Community Engagement to explore the emerging issues in health care reform as applied to mental health and substance abuse services and persons with those needs.39 Based on this commentary, Dr. Wells and Dr. Patel were invited to host a panel discussion at the 2010 Academy Health meeting on implications of health reform for mental health, from diverse stakeholder perspectives. Several representatives of the Partnered Research Center as well as investigators and policy spokespersons from other areas of the country participated in this panel and are now collaborating on publications outlining the potential impact of health reform legislation.

Partnered research efforts in mental health have also emerged in studies of care for persons with severe mental illness.29,33,40–42 Due to the historical mistreatment found in the mental health system and the medical model having traditionally viewed consumers/survivors from a deficit model rather than a strength-based model, true partnerships between academic/clinical researchers and people who have been diagnosed with serious mental illness have been difficult to forge. One consumer/survivor expressed feeling that his presence on various projects or committees was solicited more for the appearance of diversity and inclusion rather than for substantive involvement and consideration. This lack of trust has now dissipated as meaningful inclusion and respect for input from center members has grown. For example, center investigators are currently in the planning stages of a pilot to manualize an intervention designed by a consumer/survivor partner to educate peers about illness self-management, especially medication issues and advocacy. The center is supporting manualizing this intervention and future training of peers on its use and supervision of its implementation. The center has also supported a PEERS fellowship program in which three consumer/survivor specialists joined the center for a year to work as research assistants on our evaluation of the Mental Heath Services Act. Each of these research assistants made valuable contributions to the project and two of them are continuing to work with the center beyond the completion of their fellowship.

In addition, below are a selection of case studies that illustrate how the CPPR model is being applied within projects and how the structure and functions of the project or the center as a whole, become modified in response to the input and resources available as the model is applied within the center infrastructure. For each case study, we briefly describe work according to the Vision, Valley and Victory stages and comment on how the projects utilize community engagement principles.

Case Study 1: Community Partners In Care

Community Partners in Care (CPIC) is a group-level, randomized comparative effectiveness study, where the compared interventions are use of expert consultation versus community engagement and planning as models for improving dissemination of evidence-based quality improvement interventions for depression in underserved communities in Los Angeles. The project itself was designed and is being implemented within a CPPR framework with community and academic co-leads, and directed by a council that has supported working groups addressing design, measures, implementation evaluation, and intervention development and implementation.43

Vision

At the beginning of the project, CPIC conducted a visioning exercise at an executive committee meeting where study partners were given a piece of paper and asked to respond to four questions: 1) what would you as an individual expect from CPIC? 2) what are your and your agencies expectations of CPIC? 3) what do you think the community expects from CPIC? and 4) what do you think researchers/academics expect from CPIC? CPIC then held a general meeting with community stakeholders and potential partners. Participants were asked three main discussion questions to help us determine the appropriateness of the project’s depression care intervention: 1) how do you define community? 2) what agencies, organizations or individuals need to be included to develop trusted and respected community solutions to reduce depression in the community? and 3) what innovative, creative solutions do you know of – or think should be used – to improve services for depression in the community? Scribed notes were taken at this meeting and these notes were then analyzed jointly by a group composed of two academic and two community partners from the CPIC Steering Council. A final version of the result was then drafted and presented to the CPIC Steering Council. CPIC then held its first policy advisory board (PAB) meeting. The goals of the PAB as determined by the steering council were to develop institutional and community/civic support for improving depression care and using the CPIC study as a catalyst for community learning about how best to do so. These informal discussions provided a rich insight into the array of issues for policy stakeholders in considering the study’s goals and implementation in Los Angeles County.

Valley

Components of the main project, now underway, include agency, administrator, provider, and client recruitment, intervention development and implementation, survey administration for agency administrators, providers, and clients/community members, study operations and administration, and planning for main analyses and dissemination activities. Each activity is supported by working groups that are co-led by community and academic leaders, and for most meetings, and for the project as a whole, there is an emphasis on community engagement activities and relationship building. Key issues at this stage include keeping motivation across partners going across the many project activities, effectively using and motivating staff, and maintaining a balance of productivity and reaching goals and feasibility for community implementation. Examples of major adjustments owing to the CPPR framework have included adding an additional year to develop relationships with agencies to support modification of intervention materials, which has lead to a high level of participation at all levels (eg, 93 agency programs are participating across diverse types of community-based agencies and businesses) and productivity in terms of intervention training sessions, as well as completion of intervention planning activities and initiation of all phases of survey work with community input and co-leadership. We are also expanding the outcomes that we are studying to be of greater relevance to the community partners, for example, inclusion of job status, housing, and academic performance. In addition, we are expanding our inclusion criteria and sites for research to be more inclusive of vulnerable populations that are of concern in the community, such as the homeless.

Victory

Under a CPPR framework, it is important to acknowledge successes along the way, and in this case the substantial recruitment benchmarks and fielding of training conferences and programs such as webinars, have contributed substantially to building community capacity. In addition to positive feedback at such events, the community partners have received and passed on spontaneous comments from their social networks expressing appreciation and excitement for these activities. Because survey benchmarks for recruitment have been exceeded, the potential is high for this project to provide important new data on the outcomes of two models of community-based implementation of evidence-based programs.

The lessons learned from this case study in progress include that a broad randomized trial is feasible through this form of rigorous partnered research and can lead, with some adjustment for community implementation needs, to a productive and effective research study that is also viewed as contributing to community capacity in a critical area. In terms of implications for the center infrastructure, this has encouraged us to be bolder in the scale of partnered research that we propose.

Case Study 2: Post-Katrina and Rita Recovery

Vision

Dr. Benjamin Springgate was an Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) Clinical Scholar when Katrina hit his hometown of New Orleans. He continued for three years as an RWJF Clinical Scholar, and in the early months after the disaster assisted with developing health services for emergency shelters for the state of Louisiana. Our center supported a community-academic partnered rapid assessment of needs one year post-storm that included unmet mental health needs, providing methodological expertise and partnership development expertise. Subsequently, the partnership evolved into a nonprofit organization (REACH NOLA) supporting academic-community partnered programs, services, and research for health recovery following the storms.

Valley

Based on the partnership development, and with the support of the expertise of the NIMH Center, Dr. Springgate secured an RWJF grant to develop community health and resiliency centers (focusing on mental health recovery) in New Orleans and funding from the American Red Cross Hurricane Recovery Program to support mental health recovery efforts through providing training in evidence-based practices in collaboration with community agencies. With this funding, along with substantial support from the RWJF, the partners were able to provide a series of seven trainings over two years, each with follow-up supervision in multiple components of evidence-based care. Designing and delivering these trainings required bringing together many diverse groups and working out differences during a stressful time, but ultimately led to increased community services delivery and capacity building. During this time, the NIMH-partnered research center supported qualitative evaluation of program development and impact and assistance with intervention technologies and implementation. This approach is also being explored for applicability to the oil spill in the Gulf States.

Victory

American Red Cross funding was the single largest philanthropically-supported, disaster mental health grant in the Gulf States after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Together with support from RWJF, this funding enabled trainings and additional consultations to reach over 400 providers from more than 70 agencies, and resulted in the development of a new community health worker program for mental health recovery,44 as well as delivery of more than 110,000 individual mental health services to tens of thousands of community members. This work has been recognized by the leadership of SAMHSA and the Department of Health and Human Services, for its value as a model for the nation’s mental health disaster preparedness and response.45 In addition, the American Association of Medical Colleges cited the key role of this community academic partnered work in awarding its 2010 Spencer Foreman Award for Outstanding Community Service to Tulane University.46 The capacity development between New Orleans and the center, has been two-way. For example, the real-world experience gained in New Orleans has been critical for implementing the NIMH Community Partners in Care study, in which we are directly using the New Orleans community health worker model and members of CPIC and of the NIMH Center have participated in every mental health recovery training in New Orleans.

The lessons learned for the center infrastructure are related to the feasibility of applying a similar model for research development and community capacity building for real-time needs, and the value of cross-project lessons and resources to both help communities in need and support improved research strategies.

Case Study 3: Cognitive Behavioral Intervention For Trauma In Schools

Vision

The vision for Cognitive Behavioral Intervention For Trauma In Schools (CBITS) was conceptualized by a lead community partner in Los Angeles Unified School District, Dr. Marleen Wong and her unit of over 250 clinicians district-wide.47 As a psychiatric social worker for over 20 years, Dr. Wong saw many students suffering from trauma-related mental health problems and saw those problems affecting students’ ability to learn. She and her colleagues sought out research partners to develop an intervention that would address these needs. As initial meetings with this community-academic partnership emerged, the community partners defined the parameters of the intervention, with feasibility being central to the design and researchers suggesting evidence-based approaches and evaluation designs.48

Valley

What has emerged from this community-academic partnership is CBITS; an evidence-based intervention for youth exposed to violence that has all the practical aspects that allow it to be disseminated by the average school-based clinician, during the school day when counseling usually occurs, and with the limited resources and time that typically is available in schools. The center is supporting the next phase of studying ways to improve implementation of CBITS given that it is being delivered in a non-specialty mental health setting with limited organizational infrastructure to support implementation. As we pilot a quality improvement strategy to support implementation, our challenge has been in balancing the collection of new knowledge with doing research in an overtaxed service system.

Victory

As a result of positive findings from two evaluation studies demonstrating the effectiveness of CBITS,48,49 this intervention has been disseminated across the United States, from Native American reservations in New Mexico and Montana, to school districts in Madison, Wisconsin, inner city areas such as Baltimore and Chicago, rural areas including Olympia and Yakima, Washington and the post-Katrina Gulf States, as well as internationally. This partnership has been supported by NIMH funding to support ongoing research activities that are coupled with services being funded by grants such as the RWJF, Carter Foundation, and SAMHSA’s National Child Traumatic Stress Network. These funding streams have allowed CBITS partners to collaborate in developing an implementation toolkit for improving dissemination, an educational video for school staff that features community partners from education, mental health, and law enforcement, and web-based trainings and support. At the same time, research partners have studied quality improvement of CBITS implementation and factors that affect sustainability and further dissemination in schools.50,51 CBITS has been recognized by the US Department of Education as meeting the standards of the No Child Left Behind policy and has been identified as an evidence-based program by the National Child Traumatic Stress Network, the National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices, the Promising Practices Network, and the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Lessons learned from this case example for the center include the importance of applying models of community engagement across different age groups and types of infrastructures to yield a more comprehensive, overall set of evidence-based strategies to relieve public burden of mental disorders and the impact of risk factors for these disorders (eg, violence).

Unanticipated Activity: A Collaboration with the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health to Create the UCLA Center for the Study of Public Mental Health

Vision

A major goal was to create partnered research collaborations that focused on public mental health care. In particular, we intended to partner with the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health (LAC DMH) and University of Southern California (USC) in order to evaluate the impact of major policy changes on care in the County.

Valley

The implementation of the vision has proceeded in two phases. The first phase entailed the development and then implementation of an NIMH R01 to study the impact of the California Mental Health Services Act on care in Los Angeles County. Initially, the NIMH Center operations core created a partnered research-working group with the LAC DMH and USC. The working group took responsibility for the R01 development and implementation. The NIMH-funded grant followed principles of partnered research and community engagement.

The second phase developed out of this new partnership and was explicitly intended to create an infrastructure for sustainable, long-term collaborations between the LAC DMH, University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), and USC. To this end, the partners created the UCLA Center for the Study of Public Mental Health. In addition to the federal grant support, the center coalesced around a set of funded initial activities, each fully conducted in partnership with LAC DMH and USC. This new evolving center has expanded its scope beyond its original focus on the relationship between policy and client outcomes to include issues such as public stigma of mental illness and development of media communication strategies (eg, http://www.pendari.com/DMH/), consistent with but somewhat outside the scope of the NIMH Center.

Victory

The “UCLA Center for the Study of Public Mental Health: A Collaboration with the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health and USC” marked its formal creation with a conference titled, “Partnership for Mental Health: A Conference on Academic-Public Collaborations for Research on Mental Health Recovery and Wellness.” The conference focused on the ways in which patients, researchers, and providers could employ rigorous scientific methods for addressing questions of mutual concern.

Lessons learned from this case study include that the application of the partnered approach to research development can also mobilize new growth directions that can meet important independent goals of center partners and feature their priorities significantly, over and above what the NIMH Center itself could support.

Discussion

The Partnered Research Center for Quality Care, established in 2008, is just one of several research centers and programs whose inception can be traced back to the Community Health Improvement Collaborative (CHIC), established in 2003. At that time, several programs came together with the common goal of identifying an innovative approach in order to have real impact and to increase the uptake of services in underserved populations around various health issues, including depression.2 That approach, now utilized by our center, is CPPR. Since 2003, CPPR has been further refined and manualized30 and has increasingly provided the framework for center projects. Through this process we have learned that with concerted effort from academic and community partners, it is possible to build a dedicated health services research center that supports both rigorous scientific research and community engagement, with the potential to reduce the stigma often associated with seeking mental health services. It is this type of structure that has allowed CPIC, one of our affiliated R01s, to successfully engage and recruit close to 100 community-based agencies in resource-poor communities that historically have distrust of researchers and the research agenda. What began as a natural next step to the CHIC, has evolved into a formalized infrastructure that supports a broad partnership in conducting work to improve mental health outcomes and mental health care in communities. Indeed, having this extensive partnership with a range of key stakeholders has presented unforeseen opportunities and enabled the center to achieve a broader scope than initially proposed. We have found that it is feasible to conduct such work, albeit with a few challenges.

A partnered style of interaction at times requires extra effort, resources, and a commitment to work together despite the many challenges that will be encountered along the way. Being inclusive of diverse partners and stakeholders is necessary to the success of partnered work but can also lead to delays and/or conflicts as there will almost certainly be opposing perspectives that will need time to be worked out. Challenges to conducting partnered research include the time required to develop trust, accounting for unexpected changes in community-based programs and leadership, limited time and resources of community partners who may have other diverse tasks and goals as their primary focus, and mixed views of its value in academic circles.38,52 In addition, some of the known challenges of conducting such research can be even more complex when also addressing stigmatized illnesses that may not be openly discussed in vulnerable communities. The existence of a secure infrastructure to spot and address differences of opinion, misunderstandings, or conflicting interests, makes these issues more manageable under a center infrastructure as the capacity and the expertise to respond increases over time.

Through involving partners, investigators, and staff in joint activities such as book clubs and center meetings and events, and disseminating findings and a common model, the center infrastructure helps to facilitate entry of new partners and investigators into the center. There is enough common history and understanding that the legacy of one investigator more easily passes to another, and similarly, investigators are more comfortable initiating projects with partners and are more likely to have some understanding of what it means to initiate and maintain a respectful research relationship. By establishing an infrastructure dedicated to an issue or approach, the transition costs of developing new initiatives or supporting new investigators is reduced. In addition, the group affiliation of a center lends a certain identity to a new approach and allows a more uniform body of work and research voice to emerge. Support for other groups and institutions via subawards or funding of community scholars is more easily achievable when there is a dedicated infrastructure and thus can lead to economies of scale and scope such that, for a given set of resources, increased productivity can be achieved. Having even modest resources available for new work, such as in-kind staff support, can encourage investigators to take more risks, and try out new ideas, thus potentially leading to more rapid innovation. While these advantages are well known in academic institutions, there are fewer precedents for established centers that support a co-owned, academic and community infrastructure.

Partnered work has without doubt become part of our culture or the way we do business. The center is structured as a collaborative learning enterprise, with activities to promote new ideas, bring diverse opinions and resources together, facilitate academic and community investigator development, and enable rigorous internal and external review. It is striving to achieve impact in real-time through increasing community and academic partners’ capacity to engage in thoughtful, methodologically sound research around mutually identified problems in mental health. To document and disseminate the process of our work, our center developed an integrated manual for conducting CPPR, which was published in a special issue of Ethnicity and Disease in December, 2009.30 This manual is also a key resource to projects conducted within the center such as the Community Partners in Care study, and is used as a main resource for training of fellows in the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars program at UCLA, along with other books on Community-Based Participatory Research.1,3,52 While the center is still in its early stages of development, it has supported various products including publications in peer-reviewed journals, newsletters, story-books or lessons learned books, policy briefs, poems and skits performed at various community events and conferences, research proposals and contracts and grants. To share more systematically what we are learning through conducting research under a partnered center infrastructure, we are currently conducting the Partnership Evaluation Study to evaluate the impact of the center’s partnership model on center research. Through this study, and as the center develops, we are empirically evaluating whether or not this type of approach makes unique contributions to the research agenda, improves services updates, and promotes research participation and use of findings. Preliminary findings from this study will be available in the fall 2011.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank their colleagues both in the community and in academia for believing in this approach to research and for committing the extra time and effort required to make our work possible. This work was supported by NIH Research Grant # P30MH068639 and P30MH082760 funded by the National Institute of Mental Health.

References

- 1.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EP, Becker AB. Community-based participatory research: policy recommendations for promoting a partnership approach in health research. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2001;14(2):182–197. doi: 10.1080/13576280110051055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wells KB, Staunton A, Norris K, Council C. Building an academic-community partnered network for clinical services research: the Community Health Improvement Collaborative (CHIC) Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1 Suppl 1):S3–S17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bluthenthal RN, Jones L, Fackler-Lowrie N, et al. Witness for Wellness: preliminary findings from a community-academic participatory research mental health initiative. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1 Suppl 1):S18–S34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel K, Koegel P, Booker T, Jones L, Wells KB. Innovative approaches to participatory evaluation in the Witness for Wellness experience. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1 Suppl 1):S35–S42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chung B, Corbett CE, Boulet B, et al. Talking Wellness: a description of a community-academic partnered project to engage an African-American community around depression through the use of poetry, film, and photography. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1 Suppl 1):S67–S78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stockdale S, Patel K, Gray R, Hill DA, Franklin C, Madyun N. Supporting wellness through policy and advocacy: a case history of a working group in a community partnership initiative to address depression. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1 Suppl 1):S43–S53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones A, Charla F, Butler BT, Williams P, Wells KB, Rodriguez M. The Building Wellness Project: A case history of partnership, power sharing, and compromise. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1 Suppl 1):S54–S66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kataoka SH, Fuentes S, O Donoghue VP, et al. A community participatory research partnership: the development of a faith-based intervention for children exposed to violence. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1 Suppl 1):S89–S97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stockdale SE, Mendel P, Jones L, Arroyo W, Gilmore J. Assessing organizational readiness and change in community intervention research: framework for participatory evaluation. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1):136–S145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alegria M, Wong Y, Mulvaney-Day N, et al. Community based partnered research: new directions in mental health services research. Ethn Dis. 2011 (in press) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Springgate BF, Allen C, Jones C, et al. Rapid community participatory assessment of health care in post-storm New Orleans. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6):S237–S243. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asch SM, Kerr EA, Keesey J, et al. Who is at greatest risk for receiving poor-quality health care? N Engl J Med. 2006;354(11):1147–1156. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa044464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2635–2645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.United States Department of Health and Human Services. The President’s New Freedom Commission on Mental Health. Achieving the Promise: Transforming Mental Health Care in America. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell J, Schraiber R. In Pursuit of Wellness: The Well-Being Project. Sacramento, Calif: Department of Mental Health; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Dorn R, Elbogen E, Redlich A, Swanson J, Swartz M, Mustillo S. The relationship between mandated community treatment and perceived barriers to care in persons with severe mental illness. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2006;29(6):495–506. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swartz MS, Swanson JW, Hannon MJ. Does fear of coercion keep people away from mental health treatment? Evidence from a survey of persons with schizophrenia and mental health professionals. Behav Sci Law. 2004;21(4):459–472. doi: 10.1002/bsl.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: variation by ethnicity and insurance status. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1548–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miranda J, Azocar F, Organista KC, Dwyer E, Arean P. Treatment of depression among impoverished primary care patients from ethnic minority groups. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(2):219–225. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wells KB, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, Koike AK. Ethnic disparities in care for alcoholism, drug abuse, and mental health care. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:2027–2032. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.González HM, Vega WA, Williams DR, Tarraf W, West BT, Neighbors HW. Depression care in the United States: too little for too few. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(1):37–46. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wells K, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, et al. Five-year impact of quality improvement for depression: results of a group-level randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(4):378–386. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.4.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miranda J, Chung JY, Green BL, et al. Treating depression in predominantly low-income young minority women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(1):57–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Areán PA, Ayalon L, Hunkeler E, et al. Improving depression care for older, minority patients in primary care. Med Care. 2005;43(4):381. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156852.09920.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tunis SR, Stryer DB, Clancy CM. Practical clinical trials: increasing the value of clinical research for decision making in clinical and health policy. JAMA. 2003;290(12):1624–1632. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lenfant C. Clinical research to clinical practice-lost in translation? N Engl J Med. 2003;349:868–874. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa035507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zerhouni EA. Translational and clinical science – time for a new vision. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(15):1621–1623. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb053723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Institute of Medicine. Promoting Health: Intervention Strategies from Social and Behavioral Research. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones L, Wells K, Norris K, Meade B, Koegel P. The vision, valley, and victory of community engagement. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(4 Suppl 6):S3–S7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones L, Wells KB. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007;297(4):407–410. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wells KB, Jones L. Commentary: “Research” in community-partnered, participatory research. JAMA. 2009;302(3):320–321. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wells KB, Miranda J, Bruce ML, Alegria M, Wallerstein N. Bridging community intervention and mental health services research. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(6):955–963. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGlynn EA, Norquist GS, Wells KB, Sullivan G, Liberman RP. Quality-of-care research in mental health: responding to the challenge. Inquiry. 1988;25(1):157–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wells KB, Sherbourne CD, Schoenbaum M, et al. Impact of disseminating quality improvement programs for depression in managed primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283(2):212–220. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.2.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wells K, Sherbourne C, Duan N, et al. Quality improvement for depression in primary care: do patients with subthreshold depression benefit in the long run? Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(6):1149. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wells KB, Miranda J. Promise of interventions and services research: can it transform practice? Clin Psychol Sci Prac. 2006;13(1):99–104. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wasserman J, Flannery MA, Clair JM. Raising the ivory tower: the production of knowledge and distrust of medicine among African Americans. J Med Ethics. 2007;33(3):177–180. doi: 10.1136/jme.2006.016329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patel K, Wells K. Applying Health Care Reform Principles to Mental Health and Substance Abuse Services. JAMA. 2009;302(13):1463. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sullivan G, Duan N, Mukherjee S, Kirchner J, Perry D, Henderson K. The role of services researchers in facilitating intervention research. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(5):537–542. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.5.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mulvaney-Day N, Alegria M, Rappaport N. Developing systems interventions in a school setting: an application of community-based participatory research for mental health. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1 Suppl 1):S107–S117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wallerstein N. Commentary: Challenges for the field in overcoming disparities through a CBPR approach: a commentary. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1):146–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chung B, Jones L, Jones A, et al. Using community arts events to enhance collective efficacy and community engagement to address depression in an African American community. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(2):237. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.141408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wennerstrom A, Vannoy SD, Allen C, et al. Community-based participatory development of mental health outreach to extend collaborative care in post-Katrina New Orleans. Ethn Dis. 2011 (in press) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yun K, Lurie N, Hyde PS. Moving mental health into the disaster-preparedness spotlight. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(13):1193–1195. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1008304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. [Accessed February 15, 2011.];Tomorrow’s Doctors, Tomorrow’s Cures. https://www.aamc.org/initiatives/awards/2010/155710/2010_ocsa_recipient_tulane.html.

- 47.Wong M. Commentary: building partnerships between schools and academic partners to achieve a health-related research agenda. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(1 Suppl 1):S149–S153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stein BD, et al. School-based interventions for children exposed to violence. JAMA. 2003;290(19):2542. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.19.2541-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kataoka SH, Stein BD, Jaycox LH, et al. A school-based mental health program for traumatized Latino immigrant children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(3):311–318. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200303000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kataoka SH, Nadeem E, Wong M, et al. Improving disaster mental health care in schools. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6S1):S225–S229. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Langley AK, Nadeem E, Kataoka SH, Stein BD, Jaycox LH. Evidence-based mental health programs in schools: barriers and facilitators of successful implementation. School Ment Health. 2010;2(3):105–113. doi: 10.1007/s12310-010-9038-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Minkler M, Wallerstein N, editors. Community Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]