Abstract

Background

Although the epidemiology of insomnia in the general population has received considerable attention in the past 20 years, few studies have investigated the prevalence of insomnia using operational definitions such as those set forth in the ICSD and DSM-IV, specifying what proportion of respondents satisfied the criteria to reach a diagnosis of insomnia disorder.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study involving 25,579 individuals aged 15 years and over representative of the general population of France, the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain and Finland. The participants were interviewed on sleep habits and disorders managed by the Sleep-EVAL expert system using DSM-IV and ICSD classifications.

Results

At the complaint level, too short sleep (15.8%), light sleep (16.6%), and global sleep dissatisfaction (8.5%) were reported by 37% of the subjects. At the symptom level (difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep and non-restorative sleep at least 3 nights per week), 34.5% of the sample reported at least one of them. At the criterion level, (symptoms + daytime consequences), 9.8% of the total sample reported having them. At the diagnostic level, 6.6% satisfied the DSM-IV requirement for positive and differential diagnosis. However, many respondents failed to meet diagnostic criteria for duration, frequency and severity in the two classifications, suggesting that multidimensional measures are needed.

Conclusions

A significant proportion of the population with sleep complaints do not fit into DSM-IV and ICSD classifications. Further efforts are needed to identify diagnostic criteria and dimensional measures that will lead to insomnia diagnoses and thus provide a more reliable, valid and clinically relevant classification.

Keywords: Insomnia, Epidemiology, classifications, mental disorders

INTRODUCTION

Insomnia has been frequently studied in the general population of Western Europe and North America (1). Few studies, however, have used well-defined criteria to assess insomnia; its presence relies mainly on positive answers to general questions about difficulties in initiating or maintaining sleep. Sometimes frequency or severity gradations have additionally been used to determine the presence of insomnia. Some epidemiological studies have investigated the occurrence of mental disorders in relation to insomnia symptoms, mainly with the use of anxiety or depression scales (1). A high co-occurrence of insomnia symptoms and mental disorders has been reported in the general population (2–5). But few of these studies have applied an operational definition of insomnia, although current classifications, such as the DSM-IV (6), the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (7) and the International Classification of Diseases (8), provide guidelines to assess insomnia. Each classification uses a funnel-shaped structure from a huge to a narrow definition: criteria, syndromes, episodes and diagnoses. “Criteria” refer to a set of symptoms or a guideline in a given diagnosis.

“Insomnia” (like “pain”) has different meanings depending on the clinical picture presented by the subject. It can be a complaint (related to sleep quantity or quality), a symptom (part of a sleep disorder or of a mental or organic disorder) or a sleep disorder diagnosis (primary or secondary) implying the need for a differential diagnosis process. This distinction has been attempted in some epidemiological studies (2–5,9). The clinical symptoms of insomnia, as described by the classifications, apply to a large part of the general population. It is unlikely, h owever, that all of these individuals suffer from an insomnia disorder (1). Previous studies (3,10) have indicated that sleep dissatisfaction could be a better indicator of sleep pathology than insomnia criteria used by classifications like DSM-IV and the ICSD. Consequently, this report aims to document the prevalence of insomnia not only at the criterion level, but also at the complaint level and at the diagnosis level (positive and a differential diagnosis). The final objective will be to show how the differential diagnosis evaluation could be essential to recognizing the true prevalence of insomnia and to improving clinical utility of insomnia diagnoses.

METHODS

Sample

Individuals from seven European countries (France, the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain and Finland) were interviewed by telephone about their sleeping habits, sleep and health (mental and physical). Information about current medications (psychotropics, prescribed medications and over-the-counter drugs) was also collected, along with the indications as reported by the subject. In each country, a representative sample was drawn from the non-institutionalized population (Table 1). The targeted population consisted of 255,451,106 inhabitants, as of the latest census figures for each country at the time of the study. The same two-stage design was used in every country. First, phone numbers were randomly pulled according to the geographic distribution of the population per official census data available at the time. Second, the Kish selection procedure (11), a controlled selection method, was applied to maintain the representation of the sample according to age and gender and allowed for the selection of one respondent in the household. If the household member chosen by the Kish procedure refused to participate, the household was classified among the refusals, replaced by another telephone number in the same area, and the process repeated.

Table 1.

Description of the samples in each country

| Country | Target Population | Number of subjects interviewed | Number of solicited participants | Participation Rate | Date of the study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| France‡ | 45,914,509 | 5,622 | 6,966 | 80.8% | April 4, to My 12,1993 |

| United Kingdom‡ | 45,709,600 | 4,972 | 6,249 | 79.6% | June 14,1994 to October 20, 1994 |

| Germany‡ | 66,649,000 | 4,115 | 6,047 | 68.1% | January 16,1996 to October 16,1996 |

| Italy‡ | 46,332,282 | 3,970 | 4,442 | 89.4% | December 17,1996 to April 5,1997 |

| Portugal* | 8,300,000 | 1,853 | 2,234 | 82.9% | June 8, 1998 to September 5, 1998 |

| Spain‡ | 38,500,000 | 4,065 | 4,648 | 87.5% | September 28,1998 to April 1,1999 |

| Finland* | 4,045,715 | 982 | 1,256 | 78.2% | May 18, to June 30, September to October 22, 2000 |

| Total | 255,451,106 | 25,579 | 31,842 | 80.3% |

The target population was >= 15 y.o.

The target population was >= 18 y.o.

Verbal consent was obtained before the subjects were interviewed. For subjects younger than 18 years of age, the verbal consent of the parent(s) was also secured. All the studies were approved and supported by an ethics and research committee in each surveyed country: the Imperial College (UK), the Regensburg University (Germany), the San Rafaele Hospital (Italy), the Santa Maria Hospital (Portugal), the Hospital General Univ. Vall d’Hebron (Spain), the Haaga Neurological Research Centre (Finland) and a research ethics committee in Montreal (Canada) where the principal investigator (M.M.O.) was located at the time. Individuals with insufficient fluency in the national language, with a hearing or speech impairment or with an illness precluding the feasibility of an interview were excluded. The overall participation rate was 80.3% (Specific participation rates by country are in Table 1). Overall, 25,579 subjects were interviewed.

Instrument

Lay investigators performed the interviews using the Sleep-EVAL system (12,13). Sleep-EVAL is specially designed to conduct epidemiological studies of sleep habits and sleep and mental disorders in the general population. Interviews typically begin with a standard questionnaire composed of sociodemographic information, sleep/wake schedule, physical health and a series of questions related to sleep symptoms and symptoms of mental disorders. From the answers provided, the system elicits a series of diagnostic hypotheses (causal reasoning process) that are confirmed or rejected throughout further questioning and by deductions of the consequences of each answer (non-monotonic, level-2 feature). The system allows concurrent diagnoses in accordance with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, forth edition (DSM-IV) (6), the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD) (7) and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) (8). The differential diagnosis process is based on a series of key rules allowing or prohibiting the co-occurrence of two diagnoses in accordance with the classifications implemented in the system. The interview ends once all diagnostic possibilities are exhausted.

The latest validation studies were conducted with 105 patients at the Sleep Disorders Centers at Stanford University (USA) and Regensburg University (Germany) (14). Patients at the Sleep Disorders Centers were interviewed twice: 1) by physicians using the Sleep-EVAL system who did not know the diagnoses given by the Sleep-EVAL system; and 2) by a senior sleep specialist clinician using his/her expertise to give one to three main diagnoses and one to 10 main symptoms per patient. This specialist was also ignorant of the diagnosis made by the Sleep-EVAL system. The Sleep-EVAL diagnoses were later compared to those of the sleep specialists. A kappa of .93 was obtained between the Sleep-EVAL system and the sleep specialists on Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome. The sensitivity of Sleep-EVAL for OSAS was 92.5% and the specificity was 100%. For all types of sleep-disordered breathing, the sensitivity of Sleep-EVAL was 98.2% and the specificity was 95.1%. Agreement for insomnia diagnoses was obtained in 96.9% of cases (kappa 0.78).

The duration of interviews ranged from 28 to 150 minutes. The longest interviews involved subjects with sleep disorders associated with mental disorders. Interviews were completed over two or more sessions if the duration of a session exceeded 60 minutes.

Variables

At the complaint level

Complaints were assessed throughout a reported severity of sleep dissatisfaction (subjects moderately or completely dissatisfied with their sleep). For the perception of sleep as being too short or too light, use of sleep enhancing medication was also used as an exploratory criterion for dissatisfaction with the quality or quantity of sleep. The reported duration of sleep was compared to sleep schedule variables collected for all subjects of the sample.

At the symptom level

The symptoms of insomnia as described in DSM-IV and ICSD classifications were also evaluated:

Difficulty Initiating Sleep (DIS): being quite or completely dissatisfied with sleep latency (at least 30 minutes) or reporting long sleep latency at sleep onset as a major sleep problem;

Difficulty Maintaining Sleep (DMS): Difficulty in resuming sleep after awakening in the night or identification of disrupted sleep as being a major problem;

Early Morning Awakenings (EMA): short nocturnal sleep duration caused by an inability to resume sleep once awake);

Non-Restorative Sleep (NRS): sleep of normal duration associated with a complaint of being unrested upon awakening or identification of fatigue at awakening as a major problem.

All these symptoms were required to occur at a frequency of three nights per week or more.

At the criteria level

Daytime repercussions were assessed through 15 questions answered on a 5-point scale ranging from no impact to severe impact. These items covered cognitive functioning (memory, concentration, efficacy); affective tone (irritability, anxiety, depression); sensory irritability; and difficulty completing daily tasks (work, study or household). Subsequently, subjects identified which repercussions had an impact on their health, work or occupational activities, family and social life.

At the diagnosis level

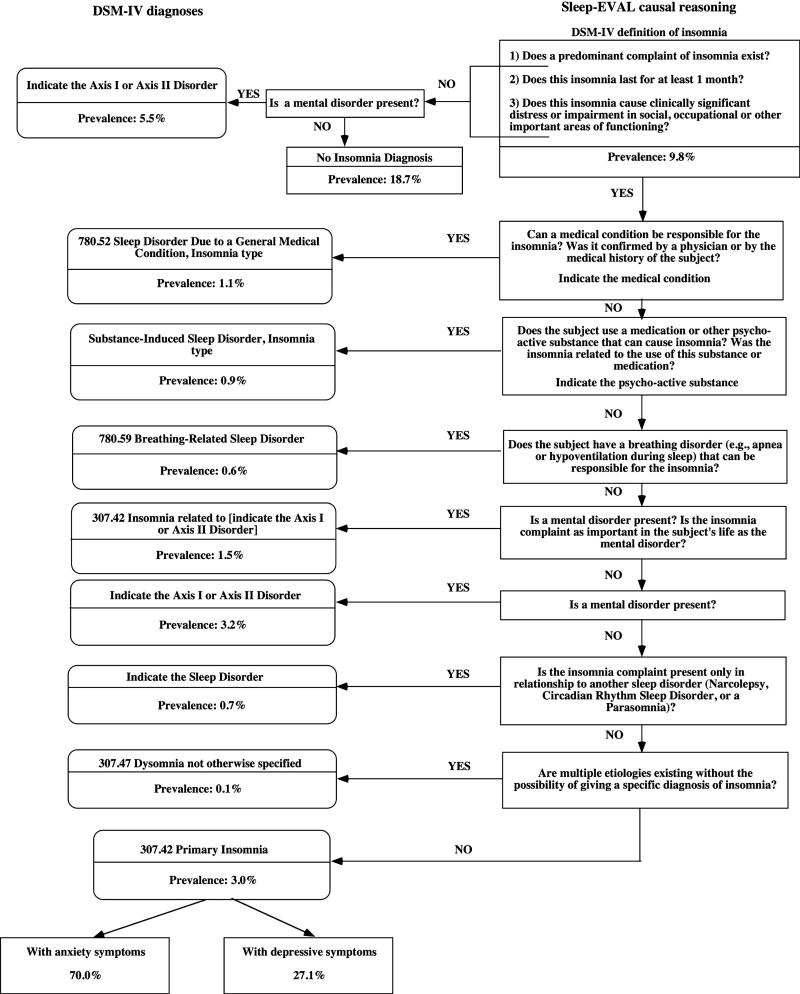

Diagnoses were based upon diagnostic criteria specified in DSM-IV and ICSD. The differential diagnosis procedure required by the classifications was also applied (see Figure 2 for DSM-IV classification). ICD-10 was used for specification of organic medical diseases.

Figure 2.

DSM-IV Sleep-EVAL decision tree

Data analyses

The data were weighted to compensate for disparities between the sample and the national census figures for the non institutionalized population. Descriptive and qualitative variables were analyzed using the chi-squared statistic. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals were calculated for prevalence rates and odds ratios of associations. Reported differences were significant at .05 or less.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics

Demographic characteristics for the whole sample are presented in Table 2. Gender and age distribution were comparable among the countries studied. The Italian, Spanish and Portuguese samples had lower rates of separated or divorced subjects than in other countries. A higher proportion of homemakers was found in the Italian and Spanish samples and, consequently, a lower rate of daytime workers compared to the other samples.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the sample

| N | % | s.e. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Female | 13295 | 52.0 | 0.29 |

| Male | 12284 | 48.0 | 023 |

| Age groups | |||

| <25 | 4606 | 18.0 | 0.40 |

| 25–34 | 4794 | 18.7 | 0.41 |

| 35–14 | 4350 | 17.0 | 0.44 |

| 45–54 | 3739 | 14.6 | 0.51 |

| 55–64 | 3400 | 13.3 | 0.54 |

| >=65 | 4690 | 18.3 | 0.45 |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | 7360 | 28.8 | 0.31 |

| Married-common law | 14284 | 55.8 | 0.25 |

| Separated-Divorced | 1316 | 5.1 | 0.98 |

| Widowed | 2616 | 10.2 | 0.66 |

| Occupation | |||

| Shift or night worker | 2018 | 7.9 | 0.70 |

| Daytime worker | 10578 | 41.4 | 0.27 |

| Unemployed | 1383 | 5.4 | 0.91 |

| Student | 2242 | 8.8 | 0.53 |

| Retired | 5142 | 20.1 | 0.43 |

| Homemaker | 4215 | 16.5 | 0.50 |

| Education | |||

| No education | 1650 | 6.4 | 0.70 |

| 9 yrs or less | 8538 | 33.4 | 0.91 |

| 11–12 yrs | 9054 | 35.4 | 0.53 |

| 13–14 yrs | 3341 | 13.1 | 0.43 |

| 15+ | 2352 | 9.2 | 0.50 |

| Master-PhD | 646 | 2.5 | 0.27 |

At the complaint level

Surveyed subjects slept on average 7 hours 9 minutes. The youngest subjects slept on average 30 minutes more than the oldest individuals of the sample (Table 3). Dissatisfaction with sleep duration was expressed by 18.2% of the sample. There was little variation between the age categories with the exception of the youngest subjects, who expressed less dissatisfaction than middle-aged individuals (35–64 y.o.). Similarly, the perception of sleep as being too short was reported by 20.2% of the sample. The prevalence significantly decreased with age.

Table 3.

Prevalence of sleep complaints and sleep duration

| Age groups

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <25 | 25–34 | 35–14 | 45–54 | 55–64 | >=65 | Total | ||||||||

| % | [95% CI] | % | [95% CI] | % | [95% CI] | % | [55% CI] | % | [95% CI] | % | [95% CI] | % | P5% CI] | |

| Sleep duration | ||||||||||||||

| < 5:00 | 1.0 | [0.7–1.2] | 2.0 | [1.6–2.3] | 2.2 | [1.8–2.7] | 3.0 | [25–3.6] | 4.6 | [3.9–5.3] | 6.2 | [5.5–6.9] | 3.1 | [2.9–3.3] |

| 5:00–5:59 | 3.9 | [3.4–4.5] | 5.3 | [4.6–5.9] | 6.7 | [6.0–7.4] | 8.1 | [7.3–9.0] | 10.0 | [9.0–11.0] | 10.9 | [10.0–11.8] | 7.3 | [7.0–7.7] |

| 6:00–6:59 | 12.4 | [11.4–13.3] | 19.7 | [18.6–20.8] | 22.7 | [21.4–23.9] | 23.8 | [22.5–25.2] | 22.0 | [20.6–23.4] | 21.0 | [19.8–22.2] | 20.0 | [19.5–20.5] |

| 7:00–7:59 | 28.3 | [27.0–29.6] | 36.1 | [34.8–37.5] | 37.6 | [36.1–39.0] | 35.2 | [33.6–36.7] | 31.3 | [29.7–32.8] | 25.7 | [24.4–26.9] | 32.3 | [31.7–32.8] |

| 8:00–8:59 | 39.0 | [37.6–40.4] | 31.0 | [29.7–32.3] | 26.8 | [25.5–28. 1] | 24.9 | [23.5–26.3] | 25.1 | [23.7–26.6] | 26.4 | [25.1–27.7] | 29.2 | [28.7–29.8] |

| ≥ 9:00 | 15.5 | [14.4–16.5] | 5.9 | [52–6.6] | 4.1 | [3.5–4.7] | 5.0 | [4.3–5.7] | 7.0 | [6.2–7.9] | 9.9 | [9.0–10.7] | 8.1 | [7.7–8.4] |

| Mean [s.d.]a | 7:30 | (1:10) | 7:12 | (1:06) | 7:03 | (1:04) | 6:59 | (1.10) | 6:56 | (1:19) | 6:58 | (1:30) | 7:09 | (1:15) |

| Dissatisfaction sleep duration.a | 16.1 | [14.3–17.3] | 17.3 | [16.0–18.5] | 19.1 | [17.7–20.5] | 20.3 | [18.8–21.8] | 19.4 | [17.9–21.0] | 17.9 | [16.6–19.2] | 18.2 | [17.6–18.7] |

| Too short sleepa | 21.3 | [19.9–22.7] | 24.4 | [23.0–25.8] | 23.9 | [19.4–22.4] | 20.9 | [19.4–22.4] | 16.1 | [14.6–17.5] | 14.0 | [12.8–15.1] | 20.2 | [19.6–20.8] |

| Light sleepa | 9.9 | [8.9–10.9] | 13.8 | [12.7–14.9] | 16.2 | [17.8–20.6] | 19.2 | [17.8–20.6] | 19.9 | [18.4–21.4] | 21.5 | [20.2–22.9] | 16.6 | [16.0–17.1] |

| Global sleep dissatisfactiona | 5.8 | [5.1–6.5] | 6.4 | [5.7–7.1] | 8.6 | [8.8–10.7] | 9.7 | [8.8–10.7] | 10 | [9.0–11.0] | 9.7 | [8.8–10.5] | 8.2 | [7.9–8.6] |

| Use of sleep medication | 1.0 | [0.7–1.3] | 1.8 | [1.5–2.2] | 3.1 | [5.4–7.0] | 6.2 | [5.4–7.0] | 9.7 | [8.7–10.7] | 14.6 | [13.6–15.6] | 5.9 | [5.6–6.2] |

p<0.0001 between age groups

The perception of having light sleep occurred in 16.6% of the sample and significantly increased with age. Global sleep dissatisfaction was reported by 8.2% of the sample. The prevalence was mostly stable across age groups; significant differences were observed only between subjects less than 35 years old and subjects 35 years and over.

At the symptom level

All subjects were queried about insomnia symptomatology according to DSM-IV and ICSD criteria, as defined by having either DIS, DMS, EMA or NRS at least 3 nights per week. These symptoms were frequently reported at a criterion level in the European sample studied. The median duration of insomnia symptoms was 60 months.

As seen in Table 4, DMS was the most commonly reported symptom with a prevalence of 23.1%. DIS, EMA and NRS were reported in similar proportions. DIS, DMS and EMA significantly increased with age, while NRS significantly decreased in the two older age groups compared to subjects aged less than 55 years.

Table 4.

Prevalence of insomnia symptoms by age groups

| Age groups

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <25 | 25–34 | 35–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | >=65 | Total | ||||||||

| % | [95% CI] | % | [95% CI] | % | [95% CI] | % | [95% CI] | % | [95% CI] | % | [95% CI] | % | [95% CI] | |

| Difficulty initiating sleepa | 10.4 | [9.5–11.3] | 7.9 | [7.2–8.7] | 8.5 | [10.0–12.0] | 8.5 | [10.0–12.0] | 11.0 | [10.0–12.0] | 13.1 | [11.9–16.0] | 10.9 | [10.5–11.2] |

| Difficulty maintaining sleepa | 12.4 | [11.5–13.4] | 15.2 | [14.2–16.3] | 18.8 | [21.8–24.5] | 23.1 | [21.8–24.5] | 33.3 | [31.7–34.9] | 38.7 | [37.3–40.1] | 23.1 | [22.6–23.7] |

| Early morning awakeningsa | 9.1 | [83–10.0] | 8.6 | [7.8–9.4] | 10.4 | [13.3–15.5] | 14.4 | [13.3–15.5] | 16.3 | [15.1–17.6] | 16.7 | [15.6–17.8] | 12.3 | [11.9–12.7] |

| Non-restorative sleepa | 12.1 | [11.1–13.0] | 11.5 | [10.6–12.4] | 11.5 | [10.9–13.0] | 11.9 | [10.9–13.0] | 9.9 | [8.9–10.9] | 9.4 | [8.5–10.2] | 11.1 | 10.7–11.5 |

| Total insomnia symptomsa | 26.6 | [25.3–27.9] | 27.2 | 25.9–28.4] | 29.6 | [28.2–30.9] | 34.4 | [32.9–36.0] | 42.0 | [40.3–43.7] | 47.7 | [46.3–49.1] | 34.5 | [33.7–34.8] |

p<0.0001 between age groups

At the diagnosis level

The DSM-IV describes the essential features of insomnia disorder as (1) being a predominant complaint of insomnia, (2) lasting for at least one month, and (3) causing significant distress or daytime impairments in social, occupational or other sectors of daily life. The presence of all three DSM-IV criteria was observed in 9.8% of the sample.

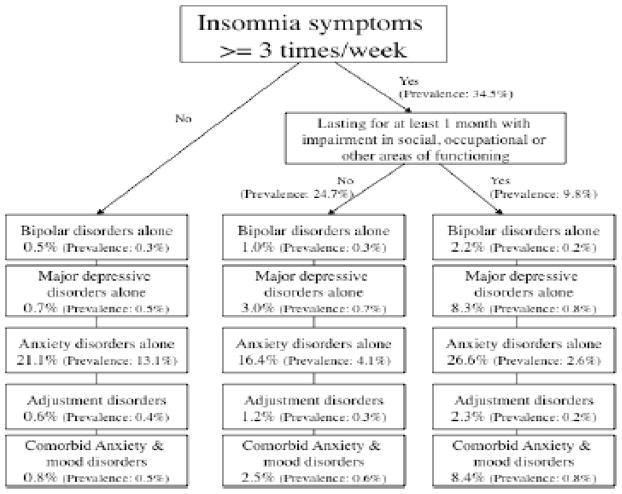

We found that about half of the subjects who met the essential DSM-IV criteria of insomnia also met criteria for a mental disorder. Anxiety disorders were the most frequent, with Generalized Anxiety Disorder accounting for about half. Mood disorders, mostly major depressive disorder, were the second most frequent disorders (Figure 1). These subjects also had the highest rate of comorbid mood and anxiety disorders. About 25% of subjects who reported insomnia symptoms for less than one month or without significant impairment of functioning had a mental disorder.

Figure 1.

Distribution of mental disorders among insomnia subjects

These rates represent the association between mental disorders and insomnia complaints regardless of the final diagnostic issue (positive diagnosis).

Subsequently, the differential diagnosis process as outlined by the DSM-IV was applied to subjects who met the three DSM-IV criteria cited above. The positive and differential diagnosis process is shown in Figure 2. As can be observed, when insomnia was accompanied by a general medical condition or substance use (or abuse) responsible for the insomnia symptoms, subjects received a diagnosis of “Sleep Disorder Due to a General Medical Condition, Insomnia type,” or a diagnosis of “Substance-Induced Sleep Disorder, Insomnia type.”

If a mental disorder was currently present, it was further determined if the insomnia complaint constituted the predominant characteristic of the symptomatology or was simply associated with it. This was ascertained using a series of additional questions assessing the importance of insomnia complaints compared with mental disorders. In the case of the former, subjects received a diagnosis of “Insomnia Related to Another Mental Disorder” and, in the case of the latter, the insomnia disorder diagnosis was ruled out and a mental disorder diagnosis was given.

Insomnia without a mental or general medical condition and without substance use (or abuse) led to a diagnosis of “Primary Insomnia.” Finally, subjects with characteristics of several forms of insomnia were classified in the “Dyssomnia not otherwise specified” category.

As can be observed in Figure 2, Primary Insomnia and Insomnia Related to Another Mental Disorder were the two most frequent diagnoses, with a prevalence of 3% for Primary Insomnia, and 1.5% for Insomnia Related to Another Mental Disorder.

The International Classification of Sleep Disorders was used in all the countries except France. As shown in Table 6, subjects with DSM-IV Primary Insomnia split mainly among three diagnoses in the ICSD: Psychophysiological Insomnia, Idiopathic Insomnia, and Insufficient sleep syndrome.

Table 6.

Prevalence of selected ICSD sleep disorder diagnoses

| Insomnia criteria resulted in: | Women | (n=10371) | Men | (n=9590) | Total | (n=19961) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | [95% CI] | % | [95% CI] | % | [95% CI] | |

| Psychophysiological Insomnia | 1.7 | [1.5–2.0] | 1.1 | [0.9–1.3] | 1.4 | [1.2–1.6] |

| Circadian rhythm disorders* | 1.0 | [0.8–1.1] | 0.7 | [0.6–0.9] | 0.8 | [0.7–1.0] |

| Idiopathic Insomnia | 0.6 | [0.5–0.8] | 0.5 | [0.4–0.6] | 0.6 | [0.5–0.7] |

| Insufficient sleep syndrome* | 0.9 | [0.7–1.1] | 0.8 | [0.6–1.0] | 0.9 | [0.7–1.0] |

| Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome*a | 1.6 | [1.4–1.9] | 2.6 | [2.3–2.9] | 2.1 | [1.9–2.3] |

| Mood disorder associated with sleep disturbances*a | 3.1 | [2.7–3.4] | 1.6 | [1.4–1.9] | 2.4 | [2.2–2.6] |

| Panic disorder associated with sleep disturbances* | 0.9 | [0.7–1.1] | 0.4 | [0.2–0.5] | 0.6 | [0.5–0.7] |

| Anxiety disorder associated with sleep disturbances*a | 1.5 | [1.3–l.8] | 0.7 | [0.5–0.8] | 1.1 | [1.0–1.3] |

Prevalence excludes positive cases without a complaint of insomnia

p<0.0001 between gender

The DSM-IV diagnosis “Insomnia Related to Another Mental Disorder” has no equivalent in the ICSD. The mental disorder diagnoses can be divided into three ICSD diagnoses: Mood disorder associated with sleep disturbances; Panic disorder associated with sleep disturbances; and Anxiety disorder associated with sleep disturbances. Thus, the prevalences between the two classifications cannot be readily compared because the diagnoses are not defined similarly.

Reported consequences of insomnia

For an insomnia diagnosis, the DSM-IV and ICSD classifications require that the subject have daytime repercussions in different areas of life (health, familial, social or work functioning) due to a sleep disturbance.

About 40% of subjects reported at least mild consequences of their insomnia symptoms. Among subjects reporting daytime consequences:

44% reported that insomnia affected their health. Nearly two-thirds (61.6%) said the impact on health was due to physical fatigue or weariness.

30% of subjects reported an impact on their work and/or daily activities. Most frequently reported causes of the impact on work or activities were physical fatigue or weariness (53.7%), mental or intellectual fatigue (49.5%), irritability (39.3%) and decreased efficiency (33.8%).

31.3% of subjects mentioned effects on family relationships. The most frequently reported causes were irritability (58.5%), physical fatigue (49.2%), mental fatigue (36.7%) and depressive mood (34.8%).

Finally, 24% said insomnia caused problems in social relationships. Main reported causes affecting social relationships were irritability (55.4%), physical fatigue (53.6%), mental fatigue (36.5%) and depressive mood (35.2%).

Association with organic (medical) diseases

Insomnia symptomatology is often exacerbated as a result of an organic disease. Musculskeletal or articular diseases (arthritis, backache, pain in limbs, etc.) were the most frequently associated: 14.6% of subjects meeting insomnia criteria suffered from such a disease as compared to 3.4% non-insomnia subjects (OR 4.9 [95% CI: 4.3 to 5.7]). Heart diseases ranked second, with 5.4% of insomnia subjects having a cardiovascular disease compared to 2.7% in the non-insomnia subjects (OR 2.1 [95% CI: 1.7 to 2.6]). Gastrointestinal diseases and pulmonary diseases were third in prevalence, with 2.3% of insomnia subjects for each disease compared to 1.0% and 0.9% respectively for the non-insomnia subjects (OR 2.30 [95% CI: 1.81 to 2.92] for gastrointestinal diseases and OR 2.41 [95% CI: 1.89 to 3.09] for pulmonary diseases).

DISCUSSION

Insomnia diagnosis (disorder) prevalence has been under-investigated in the general population

Epidemiological studies in the general population have assessed mainly insomnia symptomatology and, on rare occasions, have used sets of criteria to determine the prevalence and severity of insomnia diagnoses (disorders) (2,3,9). Furthermore, there has been no attempt to frame a differential diagnostic process to arrive at reliable insomnia diagnoses. Therefore, this large-scale study is the first to explore insomnia criteria and sleep complaints with respect to the positive and differential diagnostic processes used by two classifications (DSM-IV and ICSD).

How was DSM-IV classification able to identify candidate subjects for insomnia?

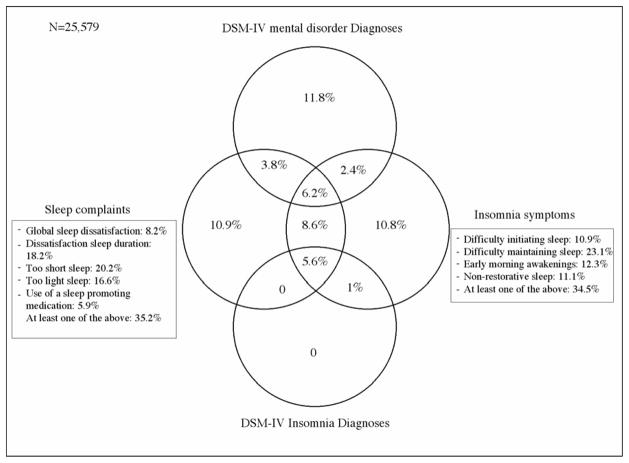

The DSM-IV classification process resulted in about 19% of the population being identified as having either an insomnia diagnosis or a mental disorder diagnosis with insomnia criteria and/or sleep complaints (Diagram 1). About 9% of subjects complained about their sleep and met insomnia criteria. This stratum of the population is of particular interest because they are potential candidates to seek help for their insomnia. Even when accounting for other sleep disorder diagnoses that need to be ruled out, we still have about 15% of the population that does not fit into a diagnostic category. Furthermore, only a third of elderly subjects with a predominant complaint of insomnia have obtained an insomnia diagnosis, in contrast to half of the younger subjects. This is likely due to a failure of the elderly to report the daytime consequences of insomnia and/or for the classifications to propose adequate criteria for this age category. It is possible that since most of them are retired, widowed or living alone, there is a reduced probability that they or others have noticed the consequences of insomnia. A possibility, offered by the DSM-IV classification, would have been to classify these subjects into the category of “Dyssomnia not otherwise specified.” But this solution is not acceptable—how indeed can we classify close to half of these subjects with complaints in a “catchall” category? At the very least, this observation suggests that further refinement is needed in the classification to better fit the reality of the population. In this context, we believe that the addition of a dimensional evaluation to each of the traditional categorical diagnoses, measuring severity, distress or impairment, would enhance the quality (reliability and validity) of the insomnia diagnosis for both clinical and research applications. For example, to assess whether a patient is responding to treatment, clinicians need the information provided by dimensional measures of severity, distress and impairment (15).

Diagram 1.

Overlapping between sleep complaints, insomnia symptoms and DSM-IV diagnoses in the general population

DSM-IV Insomnia diagnoses: Primary insomnia; Substance-induced sleep disorder, insomnia type; Insomnia related to another mental disorder; Sleep disorder due to a general medical condition, insomnia type; Dyssomnia not otherwise specified.

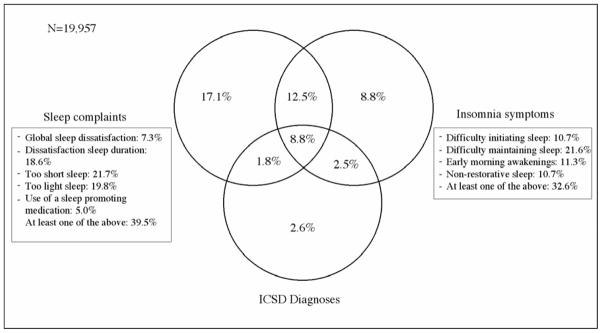

How valid is the ICSD classification in identifying insomnia subjects?

The excessive number of diagnoses in the ICSD (about 20 different diagnoses having insomnia as a main or an associated feature) resulted in a lower prevalence of these diagnoses and, therefore, a less clinically convenient (or easy to use) procedure to recognize subjects with insomnia diagnosis. Many of the diagnoses have a prevalence of less than 1% in the general population. Such is the case for idiopathic insomnia; environmental sleep disorder; sleep-onset association disorder; nocturnal eating (drinking) syndrome; hypnotic, stimulant or alcohol-dependent sleep disorders. While such nuanced classification may have its utility in specialty sleep disorder clinics, it hardly fits the reality of the general population and of general medical practice. This can be observed in Diagram 2, where 8.8% of the sample have a sleep complaint and have insomnia criteria without having a diagnosis. Furthermore, the approach to find a diagnosis of “mental disorder associated with sleep disturbances” is very different from that proposed by the DSM-IV. In the ICSD, the sleep disturbances must be caused by the mental disorder, i.e., the sleep disturbances occurred at the same time or after the mental disorder and relief is observed with the amelioration of the mental disorder. In the DSM-IV, these subjects receive a mental disorder diagnosis because the sleep disturbance is part of the mental disorder. A diagnosis of Insomnia Related to Another Mental Disorder is given only when insomnia is the predominant complaint. Usually, the subject reported that his/her insomnia bothered him/her much more than the depressive or anxious mood and that better sleep would bring an amelioration of the mood. DSM-IV begs the question whether insomnia persisting beyond the resolution of other symptoms of depression or anxiety should be classified as primary insomnia or as insomnia related to the (prior) mental disorder.

Diagram 2.

Overlapping between sleep complaints, insomnia symptoms and ICSD diagnoses in the general population

ICSD Diagnoses used: idiopathic insomnia; psychophysiological insomnia; Insufficient sleep syndrome; Mood disorder associated with sleep disturbances; Panic disorder associated with sleep disturbances; Anxiety disorder associated with sleep disturbances; Circadian rhythm disorders; Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome; Periodic limb movement disorder; Restless legs syndrome; environmental sleep disorder; sleep-onset association disorder; nocturnal eating (drinking) syndrome; hypnotic, stimulant or alcohol-dependent sleep disorders.

Almost half of our insomnia subjects reported that this sleep problem had an impact on their health mainly in the form of fatigue or weariness resulting from poor sleep. Another third reported a detrimental effect on their work or interpersonal relationships (social, friendship, family), with the two most frequently reported complaints being fatigue and irritability. Again, these issues have been poorly addressed in previous epidemiological studies, although they are well-documented consequences of insomnia in clinical studies. Daytime functioning of the insomnia patient is characterized by tiredness, without necessarily a shorter sleep onset delay at the MSLT (16,17), and concentration and memory problems (18,19).

Links with consultations and treatments

A way of knowing whether an epidemiological study is describing the reality of a complaint is to explore how many individuals are seeking medical help or are using medications to correct their problems. The use of sleep-enhancing medications varied greatly among the countries studied. Generally speaking, Mediterranean countries (France, Portugal and Italy) used such medications more frequently than did the United Kingdom and Germany. But the usage of sleep-enhancing medications increased with age in all countries and was higher in women than in men. Medical consultations for insomnia were requested by only one-fourth of insomnia diagnosis subjects. When the insomnia was related to another mental disorder, the rate of consultation increased to more than 40%. Among these subjects, 29.3% received medication, typically an antidepressant or an anxiolytic. For the 60% of subjects who did not report their sleep disturbances to their physician but who consulted him/her in the previous year, only 7.2% got a medication. This indicates that if patients do not take the initiative to let their physician know about their sleep disturbances, there is little chance that the physician will explore sleep disturbances or mental disorders in the patient. Studies conducted with general practitioners have documented this phenomenon on many occasions (19–21). The latter point and the findings of this study emphasize that educational efforts are needed to increase the recognition of sleep disorders.

Finally, given the number of people reporting chronic sleep complaints, how many are not recognized (diagnosed) by the classifications?

According to our data, a lot of them are not recognized and stay out of reach of a proper identification. This shortcoming could have several implications. First, some criteria may be missing in the classification: the four major insomnia symptoms are insufficient to explain the prevalence of sleep dissatisfaction. For example, nocturnal awakening is the most prevalent symptom of insomnia and is frequently associated with the classic insomnia symptoms (22). Second, measures of the dimensional aspects of the symptomatology are weak: more descriptive dimensions must be used. For example, classifications could use dimensions such as chronicity, severity, comorbidity, age, etc., but the most prevalent and specific dimensions are still to be defined for insomnia. Third, the primary or secondary etiology of insomnia and its comorbidity must be described and more carefully documented. Fourth, chronicity, duration and frequency are still underestimated by the two classifications: 60% of all the insomniacs of the general population have their problem for more than five years.

Limitations

Obviously, this study is not without limitations. First, lay interviewers were used to read the questions during the interviews. This situation, however, is not different from nearly all the large epidemiological studies. The main difference with other surveys is that the decision of the presence or absence of a symptom, criteria or diagnosis was taken by the Sleep-EVAL system, not the interviewer, whose only task was to enter the answers of the participant. Also, the questions were formulated in a simple manner, using everyday words, in order to be understood by individuals with little education. There are many advantages using computerized diagnostic tool, such as Sleep-EVAL, e.g., shorter assessment times, customized and standardized questionnaire administration, elimination of separate manual data entry stage, and considerable reduction in missing data. Second, the total sample is a combination of samples across surveys from seven countries. While separate analyses of the data from these national surveys indicate similar results for sleep disorders (and therefore the data can be combined), the fact remains that the sample represents a composite. Still, we believe the results indicate the strategy was defensible.

Third, the question of the reliability of sleep data collected by telephone could be raised, but the literature suggests telephone interviews in general are appropriate and yield results comparable to other strategies. Studies report survey modes appear to influence respondents equally (23–25) whether the outcome of interest is alcohol (26) or substance abuse (27). Rohde et al. (28) report good inter rater reliability between face to face and telephone interviews assessing DSM IV psychiatric disorders with adults. Fourth, in this study, sleep disorder diagnoses were based solely on self-reported symptoms. Sets of minimum criteria, as described in the ICSD and DSM-IV classifications, were used. We did not have physiological parameters on sleep generated by procedures such as electroencephalography (EEG). While such measures are desirable for some diagnoses, to date they have not been regularly incorporated into community-based, epidemiologic studies. Thus, while such data would be useful to have, self-reports and interview based measures remain the most widely used measures in community surveys. Our study was no exception. Furthermore, insomnia diagnoses do not require polysomographic results for the diagnosis.

Conclusions

Our data illustrate the importance of undertaking epidemiological studies of insomnia at several levels: complaint, criterion and diagnosis of a disorder. The distinction among these levels is of major interest:

“Complaint” reflects population demand in term of needs and can be used to evaluate the efficiency of health care providers in recognizing and meeting these needs. Study at the level of complaints may also aid in understanding the motives behind help-seeking and how help-seeking relates to symptom burden.

Study at the criterion level gives an indication of the value of grouping symptoms to define clinical entities easily and reliably recognized by health care providers. In turn, this allows for efforts at validation of diagnostic entities as specified by the classifications. An investigation of criterion level also presents the opportunity to explore manifestations of illness for which subjects may ignore or not understand the relationship between their symptomatology and pathology or impairment.

Study at the level of diagnoses allows for the possibility of evaluating the effectiveness of managing and treating disorders. The equivalent results observed between self-report complaints and classification criteria speak for validating a classification in its double role (identification, treatment), leading to better education and training of general practitioners, who are the most frequently consulted providers.

The difficulty of classification systems in correctly identifying insomnia may reflect, in part, the dilemma of society concerning the need for sleep: lost sleep versus lost time sleeping. As emphasized in the recent Institute of Medicine report, “Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: an Unmet Public Health Need” (29), our society needs to come to terms with the public health burden of insomnia and other sleep disorders. Doing so will be facilitated by the availability of measurement tools that accurately capture the true extent of the problem.

Table 5.

Prevalence of DSM-IV insomnia disorder diagnoses

| Women | (n=13295) | Men | (n= 12284) | Total | (n=25579) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insomnia criteria resulted in: | % | [95% CI] | % | [95% CI] | % | [95% CI] |

| Insomnia Disorder Diagnoses | ||||||

| • Primary Insomniaa | 39 | [3.6–4.2] | 2.0 | [1.8–2.3] | 3.0 | [2.8–3.2] |

| • Substance-Induced Sleep Disorder, Insomnia type | 1.0 | [0.9–1.2] | 0.8 | [0.6–1.0] | 0.9 | [0.8–1.0] |

| • Insomnia Related to Another Mental Disordera | 2.0 | [1.7–2.2] | 1.0 | [0.8–1.2] | 1.5 | [1.4–1.7] |

| • Sleep Disorder Due to a General Medical Condition, Insomnia typea | 1.5 | [1.3–1.7] | 0.7 | [0.6–0.9] | 1.1 | [1.0–1.2] |

| • Dyssomnia Not Otherwise Specified | 0.2 | [0.1–0.3] | 0.1 | [0.0–0.2] | 0.1 | [0.1–0.1] |

| • TOTAL insomnia diagnosesa | 8.6 | [8.1–9.1] | 4.6 | [4.2–5.0] | 6.6 | [6.3–6.9] |

|

| ||||||

| Psychiatric Diagnoses | ||||||

| Mood disorders*a | 3.8 | [3.5–4.1] | 2.4 | [2.1–2.7] | 3.1 | [2.9–3.3] |

| Anxiety disorders*a | 8.2 | [7.7–8.6] | 5.2 | [4.8–5.6] | 6.8 | [6.4–7.1] |

| Adjustment disorders*a | 0.5 | [0.4–0.6] | 0.3 | [0.2–0.4] | 0.4 | [0.3–0.5] |

Prevalence excludes positive cases without a complaint of insomnia.

p<0.0001 between gender

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01NS044199 (Dr. Ohayon).

Role of the Sponsor: The sponsors had no influence on the design, conduct, or analysis of this study.

Footnotes

Data Access and Responsibility: The first author (Dr. Ohayon) takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors had full access to all the data in the study.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of Insomnia: What We Know and What We Still Need to Learn. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:97–111. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2002.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohayon MM. Prevalence of DSM-IV diagnostic criteria of insomnia: distinguishing insomnia related to mental disorders from sleep disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 1997;31:333–346. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(97)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohayon MM, Caulet M, Priest RG, Guilleminault C. DSM-IV and ICSD-90 insomnia symptoms and sleep dissatisfaction. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:382–388. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breslau N, Roth T, Rosenthal L, Andreski P. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: a longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:411–418. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ford DE, Kamerow DB. Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders. An opportunity for prevention? JAMA. 1989;262:1479–1484. doi: 10.1001/jama.262.11.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.APA (American Psychiatric Association) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) Washington: The American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic and Coding Manual (ICSD) 2. Rochester, Minnesota: American Sleep Disorders Association; 1990. revised in 1997. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) 2. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1994. Tenth revision. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leger D, Guilleminault C, Dreyfus JP, Delahaye C, Paillard M. Prevalence of insomnia in a survey of 12,778 adults in France. J Sleep Res. 2000;9:35–42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohayon MM, Caulet M, Guilleminault C. Complaints about nocturnal sleep: how a general population perceives its sleep, and how this relates to the complaint of insomnia. Sleep. 1997;20:715–723. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.9.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kish L. Survey Sampling. New York: John Wiley & sons Inc; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohayon M. Knowledge Based System Sleep-EVAL: Decisional Trees and Questionnaires. Ottawa: National Library of Canada; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohayon M. Improving decision making processes with the fuzzy logic approach in the epidemiology of sleep disorders. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:297–311. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ohayon MM, Guilleminault C, Zulley J, Palombini L, Raab H. Validation of the Sleep-EVAL system against clinical assessments of sleep disorders and polysomnographic data. Sleep. 1999;22:925–930. doi: 10.1093/sleep/22.7.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kraemer HC. DSM categories and dimensions in clinical and research contexts. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2007;16 (Suppl 1):S8–S15. doi: 10.1002/mpr.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stepanski E, Zorick F, Roehrs T, Young D, Roth T. Daytime alertness in patients with chronic insomnia compared with asymptomatic control subjects. Sleep. 1988;11:54–60. doi: 10.1093/sleep/11.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sugerman JL, Stern JA, Walsh JK. Daytime alertness in subjective and objective insomnia: some preliminary findings. Biol Psychiatry. 1985;20:741–750. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(85)90153-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mendelson WB, Garnett D, Gillin GC, Wengartner H. The experience of insomnia and nightime functioning. Psychiatry Res. 1986;19:235–250. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(84)90029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hohagen F, Kappler C, Schramm E, Rink K, Weyerer S, Riemann D, Berger M. Prevalence of insomnia in elderly general practice attenders and the current treatment modalities. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1994;20(2):102–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Everitt DE, Avron J, Baker MW. Clinical decision-making in the evaluation and treatment of insomnia. Am J med. 1990;89:357–362. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90349-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohayon MM, Caulet M, Arbus L, Billard M, Coquerel A, Guieu JL, Kullmann B, Laffont F, Lemoine P, Paty J, Pecharde JC, Vecchierini F, Vespignani H. Are prescribed medications effective in the treatment of insomnia complaints? J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:359–368. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(98)00079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohayon MM. Nocturnal awakenings and comorbid disorders in the American general population. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;43:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crippa JA, de Lima Osório F, Del-Ben CM, Filho AS, da Silva Freitas MC, Loureiro SR. Comparability between telephone and face-to-face structured clinical interview for DSM-IV in assessing social anxiety disorder. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2008;44:241–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2008.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Senior AC, Kunik ME, Rhoades HM, Novy DM, Wilson NL, Stanley MA. Utility of telephone assessments in an older adult population. Psychol Aging. 2007;22:392–397. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.22.2.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hill J, McVay JM, Walter-Ginzburg A, Mills CS, Lewis J, Lewis BE, Fillit H. Validation of a brief screen for cognitive impairment (BSCI) administered by telephone for use in the medicare population. Dis Manag. 2005;8:223–234. doi: 10.1089/dis.2005.8.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slutske WS, True WR, Scherrer JF, Goldberg J, Bucholz KK, Heath AC, Henderson WG, Eisen SA, Lyons MJ, Tsuang MT. Long-term reliability and validity of alcoholism diagnoses and symptoms in a large national telephone interview survey. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:553–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb04292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aktan GB, Calkins RF, Ribisl KM, Kroliczak A, Kasim RM. Test-retest reliability of psychoactive substance abuse and dependence diagnoses in telephone interviews using a modified Diagnostic Interview Schedule-Substance Abuse Module. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1997;23:229–248. doi: 10.3109/00952999709040944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rohde P, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Comparability of telephone and face to face interviews in assessing axis I and II disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1593–1598. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Committee on Sleep Medicine and Research. Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: an Unmet Public Health Need. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine : National Academies Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]