Abstract

Calling 9-1-1 during an acute coronary syndrome (ACS) decreases time to treatment and may improve prognosis. Women may have more atypical ACS symptoms compared to men, but few data are available on differences in gender and ACS symptoms in calling 9-1-1. We conducted patient interviews and structured chart reviews to determine gender differences in calling 9-1-1. Calls to 9-1-1 were assessed by self-report and validated by medical chart review. Of the 476 patients studied, 292 (61%) patients were diagnosed with unstable angina (UAP) and 184 (39%) patients were diagnosed with a myocardial infarction (MI). Overall, only 23% of patients called 9-1-1. A similar percentage of women and men with UAP called 9-1-1 (15% and 13%, respectively, P = 0.59). In contrast, women with MI were significantly more likely to call 9-1-1 than men (57% vs. 28%, P < 0.001). After adjustment for sociodemographic factors, health insurance status, history of MI, left ventricular ejection fraction, GRACE score and ACS symptoms, women were 1.79 times more likely to call 9-1-1 during an MI than men (prevalence ratio 1.79; 95% C.I. 1.22 – 2.64, P < 0.01). In conclusion, the findings in the current study suggest that initiatives to increase calls to 9-1-1 are needed for both women and men.

Keywords: Acute Coronary Syndrome, Gender, Emergency Services

INTRODUCTION

Prior studies on differences in the proportion of men and women having acute coronary syndrome (ACS) who call 9-1-1 have produced inconsistent results. While some studies have found no difference in calls to 9-1-1 between women and men with ACS,1,2 other studies restricted to patients with a myocardial infarction (MI) found that women call 9-1-1 more often than men.3,4 However, there are few data that have described gender differences in calls to 9-1-1 by ACS type or by specific ACS symptom experienced. Differences in the presenting characteristics and pathobiology of patients with MI vs. unstable angina pectoris (UAP) may influence patterns of 9-1-1 calling.5 Therefore, we analyzed data from an ongoing, observational cohort of ACS patients to determine gender differences in calls to 9-1-1, and investigated whether clinical characteristics, ACS type or ACS symptoms modified these differences.

METHODS

Patients from the Prescription Use, Lifestyle, Stress Evaluation (PULSE) study at Columbia University Medical Center comprise the study population. PULSE is an ongoing, observational, single-site, prospective cohort study of the prognostic risk conferred by depressive symptoms and clinical depressive disorders at the time of an ACS. Patients with UAP, ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) or non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) by published ACC/AHA definitions6 were included and were recruited from Columbia University Medical Center within one week of hospitalization of their ACS. Between February 1, 2009 and June 30, 2010, 500 patients were recruited; 24 (5%) were excluded from these analyses because of missing data on calls to 9-1-1. The current analysis includes 476 English or Spanish speaking patients, ≥18 years of age who either presented to the emergency department at Columbia University Medical Center or were transferred from nearby hospitals. The Institutional Review Board of Columbia University Medical Center approved this study, and all participants provided informed consent.

Calling 9-1-1 was self-reported during an in-hospital interview within 7 days of admission, and was verified by review of 100 randomly selected medical records. During the interview, patients were asked whether they a) called 9-1-1, b) went to the Emergency Deparment, or c) called or went to a physician’s office at ACS onset. No other information on calling 9-1-1 was collected. Demographic, psychosocial and clinical factors were assessed within 7 days of enrollment. Age, gender, ethnicity (Hispanic or Latino vs. other), English fluency, marital status, high school education, health insurance over the prior two years and insurance with Medicaid/Medicare were assessed during a study interview. ACS symptom assessment was restricted to two typical (chest pain, arm/jaw pain) and three atypical symptoms (dyspnea, nausea/vomiting, syncope), as these five symptom clusters have been identified as independent predictors of hospital mortality;7 time course of ACS symptoms was assessed and dichotomized as constant or intermittent for analysis. ACS severity was determined using the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) risk score. The GRACE score includes age and clinical parameters at presentation (heart rate, systolic blood pressure, serum creatinine, congestive heart failure, and the presence of cardiac arrest, ST-segment elevation, and cardiac enzymes/markers) and provides an estimate of mortality within 6 months of an ACS.8 The Beck Depression Inventory was used to assess depressive symptoms; a score ≥ 10 was used to identify clinically significant depression, as this score has been independently associated with poor cardiovascular prognosis.9 History of prior MI and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) during admission was abstracted from the medical chart.

Prior studies have documented potential differences in prognosis and presentation for patients with MI vs. UAP.10,11 Therefore gender differences in calls to 9-1-1 were first examined by ACS type. As rates of 9-1-1 calling in this study were markedly different for patients with MI versus UAP, all analyses were stratified by ACS type. Patient characteristics were calculated separately for women and men. The percentage of study patients calling 9-1-1 was calculated by characteristics including age, race, ethnicity, native English speaker, marital status, completion of high school, LVEF, GRACE score, history of MI, insured over past two years, Medicare/Medicaid insurance, depressive symptoms, nausea/vomiting, syncope, constant symptoms, chest pain, arm/jaw pain and dyspnea, with the statistical significance of differences determined by t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Binomial regression was used to calculate prevalence ratios of calling 9-1-1 for women compared to men. Prevalence ratios are recommended instead of odds ratios for cross sectional studies with common outcomes.12 An initial model was unadjusted (Model 1). Subsequent models included progressive adjustment for age, race/ethnicity, public health insurance status, health insurance status within the past 2 years, high school education and marital status (Model 2); Model 2 variables and history of an MI (Model 3); Model 3 variables and ACS symptoms (nausea/vomiting, syncope and constant vs. inconstant, Model 4); Model 4 variables and LVEF/GRACE (Model 5). Variables were selected for adjustment if significant at the P < 0.10 level on calls to 9-1-1 in the unadjusted model, or if identified in prior studies as potential determinants of calls to 9-1-1 (GRACE score, marital status, insurance status).13 Among patients with an MI, subgroup analyses were performed to examine the consistency of the relationship between gender and calls to 9-1-1. Multiplicative interaction was assessed using the full population and including main effects and interaction terms (e.g., race * sex). Data on covariates was missing for 100 (21%) of participants. We used multiple imputation with chained equations and 5 data sets to account for the missing data.14,15_ENREF_18 The association between gender and 9-1-1 calling was similar using a complete case analysis (data not presented). All analyses were conducted using Stata 11 (Stata Incorporated, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics were present between women and men with UAP and between women and men with MI (Table 1). There were also significant differences in calls to 9-1-1 by baseline characteristics among patients with UAP vs. MI (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics by acute coronary syndrome type and gender.

| Unstable Angina Pectoris | Myocardial Infarction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Women (n=101) | Men (n=191) | p-value | Women (n=60) | Men (n=124) | p value |

| Age (years) | 65.9 (11.8) | 63.1 (10.9) | 0.184 | 64.3 (11.3) | 61.3 (11.6) | 0.101 |

| Black | 24% | 12% | 0.010 | 28% | 18% | 0.099 |

| Hispanic | 30% | 25% | 0.347 | 50% | 32% | 0.020 |

| Native English speaker | 73% | 72% | 0.888 | 53% | 65% | 0.127 |

| Married | 51% | 73% | <0.001 | 37% | 64% | <0.001 |

| At least high school education | 72% | 84% | 0.014 | 60% | 81% | 0.003 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | 55% (9) | 51% (10) | <0.001 | 47% (13) | 47% (12) | 0.789 |

| GRACE score | 87.6 (25.1) | 85.3 (24.4) | 0.463 | 100.3 (33.5) | 92.6 (30.3) | 0.117 |

| STEMI | NA | NA | NA | 27% | 32% | 0.440 |

| History of myocardial infarction | 29% | 31% | 0.669 | 32% | 23% | 0.163 |

| Insured over past two years | 91% | 90% | 0.888 | 92% | 89% | 0.634 |

| Medicaid/Medicare insurance | 62% | 56% | 0.378 | 65% | 52% | 0.099 |

| Current Depression* | 28% | 11% | <0.001 | 26% | 12% | 0.016 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 23% | 9% | 0.001 | 31% | 16% | 0.025 |

| Syncope | 11% | 9% | 0.575 | 12% | 11% | 0.909 |

| Constant Symptoms | 26% | 25% | 0.851 | 65% | 51% | 0.069 |

| Chest pain | 90% | 85% | 0.237 | 78% | 81% | 0.714 |

| Arm/jaw pain | 41% | 27% | 0.020 | 42% | 42% | 0.955 |

| Dyspnea | 60% | 50% | 0.099 | 43% | 39% | 0.549 |

STEMI, ST-Elevation myocardial infarction. GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Numbers in parentheses are standard deviation.

P value comparing differences across gender for unstable angina and myocardial infarction using Chi-square for categorical data and analysis of variance for continuous data

Depression by Beck Depression Inventory score ≥ 10.

Table 2.

Percent calling 9-1-1 by patient characteristics and acute coronary syndrome type

| Variable | Unstable Angina Pectoris (n=292) | P value* | Myocardial Infarction (n=184) | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| < 65 | 13% | 0.79 | 36% | 0.61 |

| >=65 | 14% | 40% | ||

|

| ||||

| Race | ||||

| Not black | 13% | 0.74 | 34% | 0.045 |

| Black | 15% | 51% | ||

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Not Hispanic | 11% | 0.026 | 32% | 0.034 |

| Hispanic | 21% | 47% | ||

|

| ||||

| Native English speaker | ||||

| No | 21% | 0.014 | 44% | 0.147 |

| Yes | 10% | 33% | ||

|

| ||||

| Marital status | ||||

| Not Married | 18% | 0.111 | 38% | 0.870 |

| Married | 11% | 37% | ||

|

| ||||

| Completed high school | ||||

| No | 28% | <0.001 | 50% | 0.052 |

| Yes | 10% | 34% | ||

|

| ||||

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | ||||

| < 50% | 13% | 0.506 | 40% | 0.643 |

| ≥ 50% | 16% | 36% | ||

|

| ||||

| GRACE score | ||||

| < 87 | 14% | 0.955 | 40% | 0.643 |

| ≥ 87 | 13% | 36% | ||

|

| ||||

| History of myocardial infarction | ||||

| No | 9% | <0.001 | 35% | 0.281 |

| Yes | 24% | 45% | ||

|

| ||||

| Insured over past 2 years | ||||

| No | 15% | 0.889 | 44% | 0.504 |

| Yes | 14% | 36% | ||

|

| ||||

| Medicare/Medicaid Insurance | ||||

| No | 7% | 0.003 | 30% | 0.134 |

| Yes | 19% | 41% | ||

|

| ||||

| Depressive symptoms | ||||

| No | 13% | 0.586 | 37% | 0.352 |

| Yes | 16% | 46% | ||

|

| ||||

| Syncope | ||||

| No | 11% | 0.009 | 35% | 0.125 |

| Yes | 29% | 52% | ||

|

| ||||

| Constant symptoms | ||||

| No | 7% | 0.001 | 24% | <0.001 |

| Yes | 32% | 48% | ||

|

| ||||

| Chest pain | ||||

| No | 8% | 0.282 | 43% | 0.419 |

| Yes | 14% | 36% | ||

|

| ||||

| Arm/jaw pain | ||||

| No | 13% | 0.560 | 39% | 0.617 |

| Yes | 15% | 35% | ||

|

| ||||

| Dyspnea | ||||

| No | 13% | 0.722 | 35% | 0.313 |

| Yes | 14% | 42% | ||

GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events

P value for differences in percentage calls to 9-1-1 across ACS type using Chi-square

Depression by Beck Depression Inventory score ≥ 10

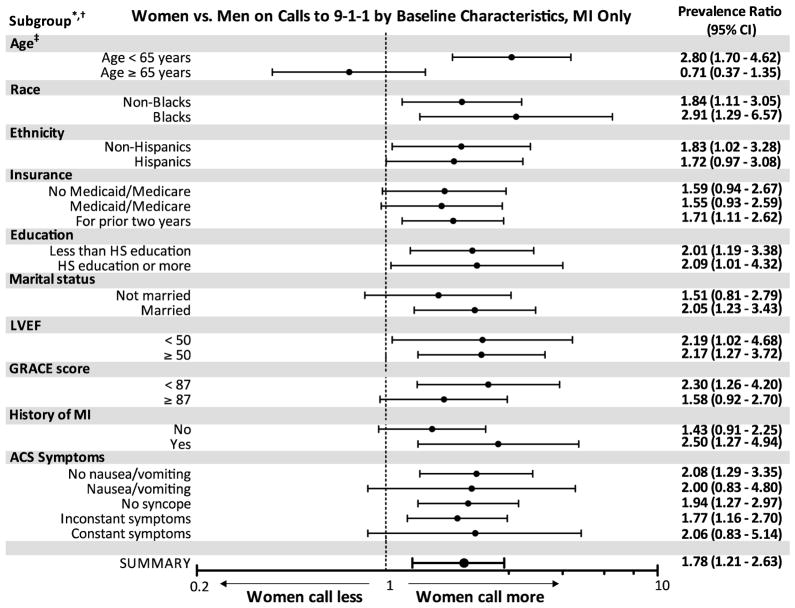

The overall percentage of calls to 9-1-1 was low, and was similar between women and men with UAP (Figure 1). In contrast, among patients with an MI, women were significantly more likely to call 9-1-1 than men.

Figure 1.

Women vs. Men on Calls to 9-1-1

Abbreviations: ACS, Acute Coronary Syndrome

P values reported for difference between women and men on calls to 9-1-1

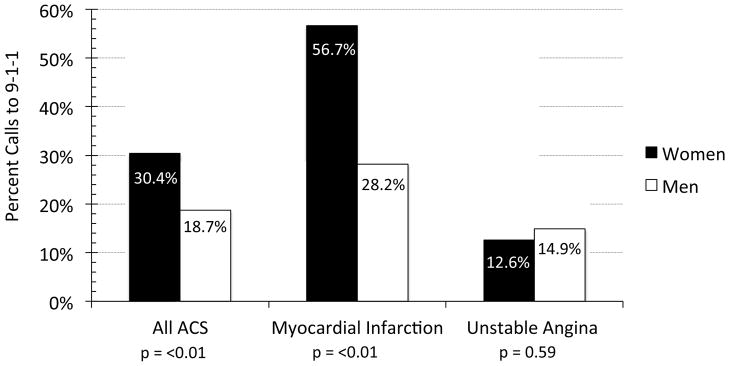

There was no difference in calls to 9-1-1 for women and men with UAP before (Model 1) or after progressive adjustment for sociodemographic factors (Model 2); history of MI (Model 3); ACS symptoms (Model 4); and LVEF and GRACE score (Model 5, Table 3). In contrast, women with an MI were more likely than men to call 9-1-1, and this difference remained statistically significant in a fully adjusted model (Model 5, Table 3). Among those with an MI, the association between gender and 9-1-1 calling was present for all sub-groups except age (Figure 2). There was an interaction of age on the association between sex and calling 9-1-1 (interaction P-value < 0.05).

Table 3.

Multivariate regression model comparing women to men on calls to 9-1-1 during an Acute Coronary Syndrome

| Unstable Angina Pectoris | Myocardial Infarction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Covariate adjustment | Prevalence Ratio (95% CI) | p value | Prevalence Ratio (95% CI) | p value |

| 1: | Unadjusted | 1.18 (0.65–2.15) | 0.585 | 2.01 (1.40–2.87) | <0.001 |

| 2: | Model 1 + sociodemographic factors* | 0.96 (0.53–1.71) | 0.879 | 1.93(1.33–2.81) | 0.001 |

| 3: | Model 2 + history of MI | 0.89 (0.50–1.59) | 0.696 | 1.93 (1.33–2.80) | 0.001 |

| 4: | Model 3 + symptoms† | 0.92 (0.51–1.65) | 0.770 | 1.80 (1.22–2.65) | 0.003 |

| 5: | Model 4 + LVEF/GRACE | 0.97 (0.51–1.84) | 0.919 | 1.78 (1.21–2.63) | 0.004 |

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction. GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events

Age (continuous), race/ethnicity, Medicaid/Medicare, insurance over the prior 2 years, education and marital status.

Symptoms include nausea/vomiting, syncope, and symptom presentation (constant vs. inconstant).

Figure 2.

Women vs. Men on Calls to 9-1-1 by Baseline Characteristics, MI only

Abbreviations: MI, myocardial infarction. HS, high school. ACS, acute coronary syndrome. LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction. GRACE, Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events

* Includes adjustment for age, race/ethnicity, education, health insurance for prior two years, Medicaid/Medicare, marital status, GRACE score, LVEF, ACS type and MI history (Model 5 covariates in Table 3)

† Subgroups estimates for syncope and no insurance for prior two years not provided because of too few events.

‡ Interaction P < 0.05

DISCUSSION

The principal findings of this investigation are that (1) less than 25% of ACS patients call 9-1-1, (2) women with an MI are more than twice as likely as men to call 9-1-1 whereas (3) the proportion of women and men calling 9-1-1 was similar for UAP.

Similar to some of our findings, studies from the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction (NRMI) have also found that women with MI were more likely than men to call 9-1-1.3,4 The current study extends data from NRMI to a contemporary cohort, demonstrating that while reported ACS symptoms may differ between women and men, ACS symptoms in this study did not explain gender differences in calls to 9-1-1. Moreover, by examining differences in calls to 9-1-1 by ACS type, the current study clarifies 9-1-1 calling among patients with different ACS presentations.2,16 The gender differences observed for patients with MI did not extend to UAP. As both UAP and MI warrant urgent medical evaluation,5 this finding indicates a specific need to increase 9-1-1 calling among all patients with an ACS.

Consistent with prior studies, we found a trend suggesting women were more likely than men to present with atypical symptoms at the time of ACS.17–20 Despite the higher prevalence of atypical symptoms among women in the current study, ACS symptom type (typical vs. atypical) did not explain gender differences in calls to 9-1-1 in the current study.

Patients with sociodemographic characteristics associated with poor health outcomes were more likely to call 9-1-1 during an ACS than patients with fewer high-risk characteristics. However, sociodemographic factors did not explain the association between gender and calls to 9-1-1 during an MI observed in this study. Women were also more likely than men to report depressive symptoms. Similar to prior findings,21 however, we did not observe an association between depressive symptoms and calls to 9-1-1.

We also observed a significant interaction between age and gender on calls to 9-1-1 for patients with an MI. Women less than 65 years of age were significantly more likely than men in the current study to call 9-1-1. However, there was no significant difference on calls to 9-1-1 between women and men over age 65 years. Compared to women over age 65, younger women may be less likely to view MI symptoms as part of aging or to misattribute MI symptoms to those of other comorbidities.22 This may lead to greater 9-1-1 calling by younger compared to older women.

There are limitations to the current study. This was a relatively small, single-center study in an urban environment, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. We did not assess whether witnesses called 9-1-1 or acted on behalf of patients enrolled in this study, or whether men were more likely than women to self-transport to the emergency department. More comprehensive description of the actions taken by patients and their families at ACS onset is warranted in future studies.

Acknowledgments

Funding & Support: This work was supported by grants HL-088117, HL-076857, HL-080665, HL-101663, and HL-084034 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and by grant T32HL007854-16 from the Health Resources and Services Administration.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Thuresson M, Jarlov MB, Lindahl B, Svensson L, Zedigh C, Herlitz J. Factors that influence the use of ambulance in acute coronary syndrome. Am Heart J. 2008;156:170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meischke H, Ho MT, Eisenberg MS, Schaeffer SM, Larsen MP. Reasons patients with chest pain delay or do not call 911. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;25:193–197. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70323-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canto JG, Zalenski RJ, Ornato JP, Rogers WJ, Kiefe CI, Magid D, Shlipak MG, Frederick PD, Lambrew CG, Littrell KA, Barron HV. Use of emergency medical services in acute myocardial infarction and subsequent quality of care: observations from the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2. Circulation. 2002;106:3018–3023. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000041246.20352.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lambrew CT, Bowlby LJ, Rogers WJ, Chandra NC, Weaver WD. Factors influencing the time to thrombolysis in acute myocardial infarction. Time to Thrombolysis Substudy of the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction-1. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2577–2582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, Bridges CR, Califf RM, Casey DE, Jr, Chavey WE, II, Fesmire FM, Hochman JS, Levin TN, Lincoff AM, Peterson ED, Theroux P, Wenger NK, Wright RS, Smith SC, Jr, Jacobs AK, Halperin JL, Hunt SA, Krumholz HM, Kushner FG, Lytle BW, Nishimura R, Ornato JP, Page RL, Riegel B. ACC/AHA 2007 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction) Developed in Collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:e1–e157. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cannon CP, Battler A, Brindis RG, Cox JL, Ellis SG, Every NR, Flaherty JT, Harrington RA, Krumholz HM, Simoons ML, Van De Werf FJ, Weintraub WS, Mitchell KR, Morrisson SL, Anderson HV, Cannom DS, Chitwood WR, Cigarroa JE, Collins-Nakai RL, Gibbons RJ, Grover FL, Heidenreich PA, Khandheria BK, Knoebel SB, Krumholz HL, Malenka DJ, Mark DB, McKay CR, Passamani ER, Radford MJ, Riner RN, Schwartz JB, Shaw RE, Shemin RJ, Van Fossen DB, Verrier ED, Watkins MW, Phoubandith DR, Furnelli T. American College of Cardiology key data elements and definitions for measuring the clinical management and outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes. A report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Acute Coronary Syndromes Writing Committee) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:2114–2130. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01702-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brieger D, Eagle KA, Goodman SG, Steg PG, Budaj A, White K, Montalescot G. Acute coronary syndromes without chest pain, an underdiagnosed and undertreated high-risk group: insights from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Chest. 2004;126:461–469. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.2.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eagle KA, Lim MJ, Dabbous OH, Pieper KS, Goldberg RJ, Van de Werf F, Goodman SG, Granger CB, Steg PG, Gore JM, Budaj A, Avezum A, Flather MD, Fox KA. A validated prediction model for all forms of acute coronary syndrome: estimating the risk of 6-month postdischarge death in an international registry. J Am Med Assoc. 2004;291:2727–2733. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berkman LF, Blumenthal J, Burg M, Carney RM, Catellier D, Cowan MJ, Czajkowski SM, DeBusk R, Hosking J, Jaffe A, Kaufmann PG, Mitchell P, Norman J, Powell LH, Raczynski JM, Schneiderman N. Effects of treating depression and low perceived social support on clinical events after myocardial infarction: the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) Randomized Trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2003;289:3106–3116. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldberg RJ, Currie K, White K, Brieger D, Steg PG, Goodman SG, Dabbous O, Fox KA, Gore JM. Six-month outcomes in a multinational registry of patients hospitalized with an acute coronary syndrome (the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events [GRACE]) Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:288–293. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fox KA, Anderson FA, Jr, Goodman SG, Steg PG, Pieper K, Quill A, Gore JM. Time course of events in acute coronary syndromes: implications for clinical practice from the GRACE registry. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;5:580–589. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:21–34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dracup K, McKinley S, Riegel B, Moser DK, Meischke H, Doering LV, Davidson P, Paul SM, Baker H, Pelter M. A Randomized Clinical Trial to Reduce Patient Prehospital Delay to Treatment in Acute Coronary Syndrome. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:524–532. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.852608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values: update of ice. The Stata Journal. 2005:527–536. [Google Scholar]

- 15.White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: Issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30:377–399. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meischke H, Dulberg EM, Schaeffer SS, Henwood DK, Larsen MP, Eisenberg MS. ‘Call fast, Call 911’: a direct mail campaign to reduce patient delay in acute myocardial infarction. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1705–1709. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.10.1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Canto JG, Goldberg RJ, Hand MM, Bonow RO, Sopko G, Pepine CJ, Long T. Symptom presentation of women with acute coronary syndromes: myth vs reality. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2405–2413. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.22.2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canto JG, Rogers WJ, Goldberg RJ, Peterson ED, Wenger NK, Vaccarino V, Kiefe CI, Frederick PD, Sopko G, Zheng ZJ. Association of age and sex with myocardial infarction symptom presentation and in-hospital mortality. J Am Med Assoc. 2012;307:813–822. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dey S, Flather MD, Devlin G, Brieger D, Gurfinkel EP, Steg PG, Fitzgerald G, Jackson EA, Eagle KA. Sex-related differences in the presentation, treatment and outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndromes: the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Heart. 2009;95:20–26. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2007.138537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackay MH, Ratner PA, Johnson JL, Humphries KH, Buller CE. Gender differences in symptoms of myocardial ischaemia. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:3107–3114. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bunde J, Martin R. Depression and prehospital delay in the context of myocardial infarction. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:51–57. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000195724.58085.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dracup K, Moser DK. Beyond sociodemographics: factors influencing the decision to seek treatment for symptoms of acute myocardial infarction. Heart Lung. 1997;26:253–262. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(97)90082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]