Abstract

Introduction:

This study investigated the associations of trajectories of cigarette smoking over the high school years with the prior development of childhood sensation seeking and the subsequent use of cigarettes and hookah at age 20/21.

Methods:

Participants (N = 963) were members of a cohort-sequential longitudinal study, the Oregon Youth Substance Use Project. Sensation seeking was assessed across 4th–8th grades and cigarette smoking was assessed across 9th–12th grades. Cigarette and hookah use was assessed at age 20/21 for 684 of the 963 participants.

Results:

Four trajectory classes were identified: Stable High Smokers (6%), Rapid Escalators (8%), Experimenters (15%), and Stable Nonsmokers or very occasional smokers (71%). Membership in any smoker class versus nonsmokers was predicted by initial level and growth of sensation seeking. At age 20/21, there was a positive association between smoking and hookah use for Nonsmokers and Experimenters in high school, whereas this association was not significant for Stable High Smokers or Rapid Escalators.

Conclusions:

Level and rate of growth of sensation seeking are risk factors for adolescent smoking during high school (Stable High Smokers, Rapid Escalators, and Experimenters), suggesting the need for interventions to reduce the rate of increase in childhood sensation seeking. For those who were not already established smokers by the end of high school, hookah use may have served as a gateway to smoking.

INTRODUCTION

In 2011, the lifetime prevalence of cigarette smoking in 8th grade was 18.4% rising to 40.0% by 12th grade (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2012), indicating the importance of understanding the patterns of growth in smoking across this developmental period. The present study investigated individual trajectory classes of cigarette smoking across adolescence, and examined their precursors and consequences. The findings could potentially suggest optimal subgroups to target for interventions to prevent, postpone, or reduce the growth of tobacco use during this vulnerable developmental stage (Brook, Zhang, Brook, & Finch, 2010). Specifically, the present study examined the prediction of membership in each trajectory in high school from the prior development of sensation seeking, and the relation between trajectory membership and subsequent use of hookah in combination with smoking at age 20/21.

Smoking Trajectories in Adolescence

Trajectory classes are an efficient way to describe the development of adolescent smoking. Because trajectories are person centered, individuals can be classified into one of several classes based on their growth across the period. Previous studies have found that for those who are already smoking at entry into high school, trajectory classes differ on level and steepness of escalation. For those who start high school as nonsmokers, classes differ on early or later onset and subsequent steepness of escalation. Most studies across adolescence and emerging adulthood have identified three to six distinct classes, including nonsmokers. For example, Abroms, Simons-Morton, Haynie, and Chen (2005) found five trajectory classes describing the development of smoking from middle school to the first year of high school (6th–9th grade). In their study from 6th/7th grade to 10th/11th grade, Colder et al. (2001) identified five classes in addition to Stable Nonsmokers. Guo et al. (2002) also found five trajectory classes across ages 13–18 years. Recently, Heron, Hickman, Macleod, and Munafò (2011) identified three distinct patterns of smoking initiation from ages 14 to 16 years: experimenters, late-onset regular smokers, and early-onset regular smokers. Trajectory classes that show decline or quitting are more likely to be found in studies encompassing longer time spans (Brook, Balka, Ning, & Brook, 2007; Brook et al., 2008; Brook, Ning, & Brook, 2006; Chassin, Presson, Pitts, & Sherman, 2000; Orlando, Tucker, Ellickson, & Klein, 2005; White, Pandina, & Chen, 2002).

Sensation Seeking as an Etiological Variable

Sensation seeking is the tendency to seek out experiences and situations that are novel, exciting, or rewarding. An examination of change across development indicates a curvilinear pattern: sensation seeking typically increases during childhood and early adolescence but then levels off and declines in late adolescence and adulthood (Harden & Tucker-Drob, 2011; Steinberg et al., 2008; Zuckerman, Eysenck, & Eysenck, 1978). Novel experiences are highly rewarding for sensation seekers, and risky behavior such as substance use is one way to obtain such rewards (Roberti, 2004; Steinberg et al., 2008; Zuckerman, 1996). Sensation seeking, treated as a stable trait, has been associated with underage cigarette smoking in numerous cross-sectional and prospective studies (e.g., Frankenberger, 2004; Kraft & Rise, 1994; Newcomb & McGee, 1991; Stephenson, Hoyle, Palmgreen, & Slater, 2003; Zuckerman, Ball, & Black, 1990). The development of sensation seeking in relation to subsequent smoking has been much less studied (Crawford, Pentz, Chou, Li, & Dwyer, 2003). Explanatory mechanisms for the association between sensation seeking and the initiation of smoking include heightened reward sensitivity to nicotine, underestimation of risk, consorting with other sensation-seeking peers, and expectancies for positive reinforcement from smoking (Doran et al., 2012; Perkins et al., 2008; Wills, Windle, & Cleary, 1998; Yanovitzky, 2005).

Theoretically, personality traits such as sensation seeking are key variables in chains-of-risk etiological approaches to the development of substance use (Burk et al., 2011; Tarter & Vanyukov, 1994; Zucker, Donovan, Masten, Mattson, & Moss, 2008). Traits are typically included as distal variables that are related to more proximal predictors of substance use (e.g., intention and willingness) through various biological, psychological, and social processes (Hampson, Andrews, & Barckley, 2007; Hampson, Andrews, Barckley, & Severson, 2006; Wills, Vaccaro, & McNamara, 1994; Zucker et al., 2008). However, personality development is occurring concurrently with these intermediate processes, likely in a reciprocal fashion (Klimstra, Akse, Hale, Raaijmakers, & Meeus, 2010). Indeed, personality traits are least stable in childhood (Roberts & DelVecchio, 2000), so to treat them as fixed entities in etiological models, as has been typically the case, may be misleading.

Hookah Use

This study also investigated the association between adolescent trajectory class membership and cigarette and hookah (water pipe) use at age 20/21. Despite a long history in some other parts of the world, in the United States, hookah is a relatively novel form of tobacco use that is increasingly popular with youth and is perceived as less risky than cigarette smoking (Primack et al., 2012; Sutfin et al., 2011). However, relative to cigarette smoking, hookah smoking is associated with more carbon monoxide and more smoke exposure, but is similar in nicotine exposure (Eissenberg & Shihadeh, 2009) and thus is as harmful as cigarette smoking. Hookah use is associated with concurrent cigarette smoking among ever-smokers (Sterling & Mermelstein, 2011).

The Present Study

This study extends past research by studying the etiological significance of the changes in sensation seeking during childhood for adolescent smoking trajectories. The analytic approach takes advantage of the longitudinal cohort-sequential design enabling the study of both sensation seeking and smoking as dynamic variables changing in level and rate of growth over time. Initial level and growth of sensation seeking from 4th to 8th grade were used as predictors of trajectory classes of cigarette smoking based on initial level and growth over 9th–12th grade. Based on past research, in addition to a nonsmoker class, four or five distinct classes that differed on timing of initiation, level, and rate of escalation were expected. Because gender differences have been observed in adolescent smoking patterns (Johnston et al., 2012) and in the association between sensation seeking and smoking (Doran et al., 2011), the effects of gender were examined in all the predictive models. In addition, because the prevalence of adolescent smoking varies as a function of parental socioeconmic status (SES) (Soteriades & DiFranza, 2003), we included free or reduced lunch, an indicator of SES, as a covariate in all models. For those participants who had already completed the assessment at age 20/21, membership in the adolescent smoking classes was related to age 20/21 hookah use and cigarette use.

METHOD

Design and Sample

The sample consisted of 963 children (487 girls and 476 boys) from the Oregon Youth Substance Use Project, 684 of whom had completed the age 20/21 assessment at the time of this report. This is a longitudinal investigation of the etiology of substance use for which five grade cohorts (1st–5th grades at the first assessment) of students from 15 elementary schools within one school district in Western Oregon were recruited and assessed annually or biennially. At age 20/21, participants were invited for an extensive in-person assessment at Oregon Research Institute. These assessments are ongoing. Using stratified random sampling (by school, grade, and gender), 2,127 students were invited to participate via invitations to their parents. Parents of 1,075 children gave consent for their child to participate (50.7%). At the first assessment (T1), an average of 215 students in each of the grade cohorts participated (N = 1,075; 50.3% female) and the mean age at T1 was 9.0 years (SD = 1.45). Participants were representative of children in the school district in terms of race/ethnicity (i.e., primarily White) and participation in the free or reduced school lunch program (40%), but the 3rd and 5th grade cohorts had slightly higher achievement test scores on reading and math (for more details, see Andrews, Tildesley, Hops, Duncan, & Severson, 2003).

To be included in the present study, participants had to have participated in at least one assessment when they were in 9th–12th grades. The comparison of these 963 children with the 112 not included in this study (10% attrition) showed no differences on gender, free or reduced lunch, ethnicity, or sensation seeking. Cohort differences examined at each grade identified only a few nonsystematic differences in sensation seeking, and no differences for smoking, so annual assessments were collapsed across cohorts to model the growth of sensation seeking from 4th to 8th grade and the growth of smoking across 9th–12th grade.

Measures and Procedures

Sensation Seeking

This trait was measured by self-report questionnaire using three high-loading items from the Thrill and Adventure seeking subscale of the Sensation Seeking scale for elementary and middle school children developed by Russo et al. (1993): like (or not) to try skiing, parachuting, and scary things. In a fourth item, participants chose one of five pictures of a stick figure jumping off an increasingly high wall to indicate the height from which they would be comfortable jumping (Bush & Iannotte, 1992). Responses to this item were standardized, and then rescaled to the mean and SD of the mean of the three questionnaire items to create a 4-item scale. Internal reliability, assessed by coefficient alpha for each grade group ranged from .58 to .66, was deemed acceptable given the small number of items.

Tobacco Use

At each assessment, participants indicated the frequency with which they had smoked cigarettes in the past 12 months: 0 = never, 1 = once, 2 = a couple of times, 3 = some each month, 4 = some each week, and 5 = some each day. The validity of this item as a measure of substance use has been demonstrated in numerous studies (e.g., Andrews, Hampson, Barckley, Gerrard, & Gibbons, 2008; Andrews, Hampson, & Peterson, 2011). At age 20/21, participants were also asked this question with respect to hookah use.

Written informed consent for their child’s participation was obtained from parents, and children could decline to participate in any of the assessments. The study was approved by the Internal Review Board at Oregon Research Institute. At T1, students in 4th grade and 5th grade completed a written questionnaire at school in group sessions. The questions were read aloud by a trained monitor and another monitor answered questions on an individual basis. At T2–T10, students still attending school in the same district were assessed at school; if they were absent on assessment day or lived outside the district, they were assessed at Oregon Research Institute, by phone (if they were in grade school or middle school), or by mail (if they were in high school). As reported by Andrews et al. (2003), the intraclass correlations within elementary schools at T1 for having tried cigarettes was low (.005), so school was not included as a variable in the analyses. The age 20/21 questionnaire was completed as part of an extensive in-person assessment conducted at the Oregon Research Institute.

Analysis Strategy

We used latent class growth analysis (LCGA; Nagin, 2005) to identify trajectory classes of cigarette use in high school (9th–12th grade) and latent growth modeling (Muthén, 1991) to examine the growth of sensation seeking in elementary school (4th–8th grade). Models were analyzed with Mplus v. 5.21 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998/2009) with the maximum likelihood method, using the Expectation Maximization algorithm for missing data (Dempster, Laird, & Rubin, 1977). LCGA is a special case of growth mixture modeling where the variance and covariance estimates for the growth factors within each class are fixed at zero. Participants were assigned to the trajectory class for which they had the highest posterior probability of membership.

Logistic regressions were used to predict trajectory class membership using a series of orthogonal comparisons. Backward elimination was used to simplify models, first removing nonsignificant interactions of level and slope of sensation seeking with gender, followed by nonsignificant main effects of sensation seeking. Gender, smoking status in the 4th grade, and whether or not participants received free or reduced lunch as reported by school administrators on at least two of the assessments (an indicator of SES) were retained in all models as control variables. The factor scores representing the initial level and linear slope for sensation seeking were saved from the latent growth analyses and used as predictors in the regression analyses. The associations between trajectory class membership and cigarette smoking and hookah use at age 20/21 were examined with chi-square test.

RESULTS

Smoking Trajectory Classes

In Table 1, we report three criteria to determine the number of classes (Hix-Small, Duncan, Duncan, & Okut, 2004; Muthén & Muthén, 2000; Nagin, 2005; Nylund, Asparouhov, & Muthén, 2007). Although the Bayesian information criterion was lower for the five-class solution than the four-class solution, entropy was higher, and the Lo-Mendell-Rubin test was not significant indicating that five-class solution was not an improvement, so the four-class solution was chosen.

Table 1.

Model Fit of Latent Class Growth Models for Cigarette Smoking in High School

| Class | BIC | E | Adj. LMRT |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12,151 | ||

| 2 | 9,749 | 0.972 | 2,310.00* |

| 3 | 8,968 | 0.964 | 764.50* |

| 4 | 8,587 | 0.964 | 382.89** |

| 5 | 8,350 | 0.958 | 124.27 |

Note. BIC = Bayesian information criterion (lower values indicate better fit); E = entropy (higher values indicate better fit); Adj. LMRT = adjusted Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test, which indicates whether there is a statistically significant improvement in fit with the inclusion of an additional class.

*p < .001. **p < .01.

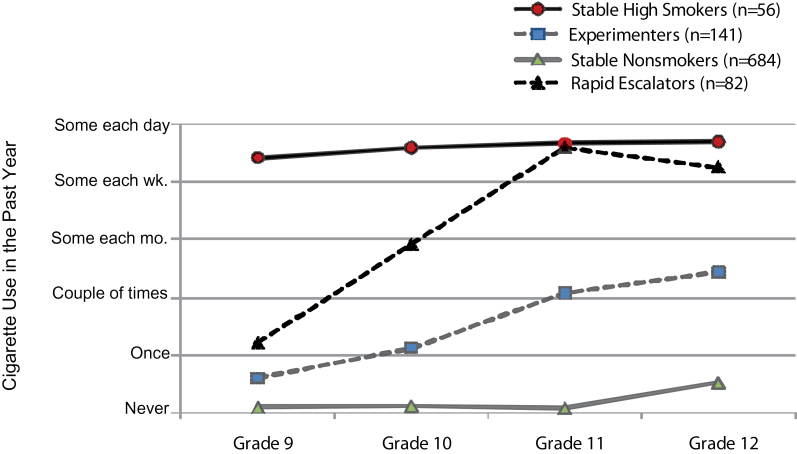

The largest class (N = 684, 71%), Stable Nonsmokers, either did not smoke cigarettes at all across high school or only very rarely. Experimenters (N = 141, 15%) started high school having smoked on average less than one cigarette and increased modestly to smoking between twice a year and less than some each month. Rapid Escalators (N = 82, 8%) began high school using cigarettes only once or twice a year but by 12th grade were smoking some cigarettes each week. Stable High Smokers (N = 56, 6%) maintained their level of smoking some cigarettes most days throughout high school. Figure 1 shows the sample mean values at each grade for the four cigarette classes.

Figure 1.

Trajectory classes for growth of cigarette smoking over high school.

Latent Growth of Sensation Seeking

The estimated means for sensation seeking at each grade suggested linear growth (4th grade: M = 1.47, SD = 0.31; 5th grade: M = 1.53, SD = 0.30; 6th grade: M = 1.62, SD = 0.29; 7th grade: M = 1.68, SD = 0.30; 8th grade: M = 1.74, SD = 0.28). A linear growth model fit the data well, confirming increasing levels of sensation seeking across 4th–8th grade, χ2 (10, n = 963) = 40.84, p < .01; comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.97, root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.06; 90% CI = 0.04, 0.08, but the fit of the quadratic model, χ2 (4, n = 963) = 4.22, p > .05; CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = 0.00; 90% CI = 0.00, 0.03, was a significant improvement over the linear model,  (6) = 36.62, p < .01. The means and variances of the intercept, linear (slope), and quadratic parameters were all significant (Mi = 1.46, t = 139.54; Ms = 0.09, t = 9.45; Mq = −0.01; Di = 0.06, t = 8.23; Ds = 0.03, t = 4.68; Dq = 0.001, t = 5.03). The intercept and slope were significantly and negatively correlated, indicating that lower initial levels of sensation seeking were associated with faster increases across grades (r = −.41, p < .01). The intercept and quadratic parameters were significantly but positively correlated (r = .26, p < .05), indicating that a lower initial level of sensation seeking was related to a downturn in middle school. The slope and the quadratic parameters were significantly and negatively correlated (r = −.93, p < .000) indicating that higher increases in sensation seeking were also associated with a downturn in late middle school. Since the linear and quadratic factors were highly correlated, the quadratic component was retained in model, but only the factor scores from the intercept and linear slope were used in further analyses (see http://statmodel.com).

(6) = 36.62, p < .01. The means and variances of the intercept, linear (slope), and quadratic parameters were all significant (Mi = 1.46, t = 139.54; Ms = 0.09, t = 9.45; Mq = −0.01; Di = 0.06, t = 8.23; Ds = 0.03, t = 4.68; Dq = 0.001, t = 5.03). The intercept and slope were significantly and negatively correlated, indicating that lower initial levels of sensation seeking were associated with faster increases across grades (r = −.41, p < .01). The intercept and quadratic parameters were significantly but positively correlated (r = .26, p < .05), indicating that a lower initial level of sensation seeking was related to a downturn in middle school. The slope and the quadratic parameters were significantly and negatively correlated (r = −.93, p < .000) indicating that higher increases in sensation seeking were also associated with a downturn in late middle school. Since the linear and quadratic factors were highly correlated, the quadratic component was retained in model, but only the factor scores from the intercept and linear slope were used in further analyses (see http://statmodel.com).

Relating Childhood Sensation Seeking to High School Smoking Trajectory Classes

We tested three orthogonal models (a) Stable High Smokers, Experimenters, and Rapid Escalators versus the Nonsmokers; (b) Stable High Smokers versus Rapid Escalators and Experimenters; and (c) Rapid Escalators versus Experimenters. Across all three models, the interactions of the intercept and slope of sensation seeking with gender were not significant. Table 2 presents the final simplified models with nonsignificant interactions of intercept and slope of sensation seeking with gender removed.

Table 2.

Regression Parameters (B) and Odds Ratios (OR) for Trait Predictors in Elementary School for Cigarette Smoking Class Comparisons in High School

| Contrast 1 | Contrast 2 | Contrast 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All smokers (n = 249) vs. Nonsmokers (n = 684) | Stable High Smokers (n = 56) vs. Rapid Escalators and Experimenters (n = 223) | Rapid Escalators (n = 82) vs. Experimenters (n = 141) | ||||

| Predictors | B | OR [95% CI] | B | OR [95% CI] | B | OR [95% CI] |

| Gender | 0.36* | 1.44 [1.05, 1.96] | 0.76* | 2.13 [1.08, 4.21] | 0.65* | 1.91 [1.04, 3.50] |

| Tried cigarettes at grade 4 | 0.44 | 1.55 [0.79, 3.06] | 1.56** | 4.78 [1.65, 13.88] | 0.65 | 1.92 [0.44, 8.39] |

| Free or reduced lunch | 0.38* | 1.46 [1.09, 1.96] | 0.71** | 2.04 [1.05, 3.72] | 0.86** | 2.36 [1.33, 4.18] |

| Sensation seeking-I | 3.09*** | 21.96 [9.40, 51.35] | 1.06 | 2.90 [0.46, 18.43] | 0.34 | 1.40 [0.27, 7.23] |

| Sensation seeking-S | 3.63*** | 37.78 [7.37, 193.59] | −2.71 | 0.07 [0.00, 2.27] | 0.25 | 1.28 [0.05, 31.7] |

Note. For all contrasts, the first-named group was coded 1. A positive B indicates that variable predicts greater odds of being in the first class rather than the second. Gender coded: male = 0, female = 1. I = intercept, S = slope. Results are for models with the nonsignificant interactions between sensation seeking and gender removed.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Girls were more likely than boys to be members of a smoker class compared with the Nonsmoker class (contrast 1), to be in the Stable High Smoker class compared with the Rapid Escalators plus Experimenters (contrast 2), and to be in the Rapid Escalator class compared with the Experimenter class (contrast 3). Having already tried cigarettes by 4th grade was only a significant predictor in contrast 2: those who had already tried cigarettes were more likely to be a Stable High Smoker as opposed to a Rapid Escalator or Experimenter. Having been on the free or reduced lunch program predicted membership in any smoker class (contrast 1), in the Stable High Smoker class (contrast 2), and in the Rapid Escalator class (contrast 3) compared with the respective contrast classes. Higher initial level (intercept) of sensation seeking increased the likelihood of being in any smoker class compared with being a Nonsmoker (contrast 1). Higher initial level (intercept) and rate of growth (slope) of sensation seeking increased the likelihood of being in any smoker class compared with being a Nonsmoker (contrast 1). Because the intercept and slope covaried, to illustrate the independent effects of one, the effect of the other was held constant at the mean. The odds of membership in any smoker class for those 1 SD above the mean and those 1 SD below the mean of the intercept, with the slope held constant at the mean, were 0.48 and 0.14, respectively. Similarly, the odds of membership in any smoker class for those 1 SD above the mean and 1 SD below the mean of the slope, with the intercept held constant at the mean, were 0.37 and 0.18, respectively. The odds of membership in any smoker class at the mean of both the intercept and slope was 0.26. Neither the intercept nor the slope of sensation seeking distinguished between classes of smokers in either contrast 2 or 3.

High School Smoking Trajectories and Cigarette and Hookah Use at Age 20/21

Of the 684 participants who had completed the age 20/21 assessment, 49% reported never having smoked cigarettes in the past year, 19% smoked once or a couple of times in the past year, 10% smoked some each month or week, and 22% smoked some each day. For hookah use, 57% reported no use in the past year, 37% reported using once or a couple of times, 6% reported using each month or week, and three people reported daily use. Table 3 shows the percentage of each high school smoking trajectory class smoking cigarettes only, using hookah only, using both, and using neither at age 20/21. Members of the high school smoking classes were more likely to have smoked cigarettes more than once in the past year than those in the Nonsmoker class, χ2 (3) = 147.52, p < .001, and members of the Nonsmoker and Experimenter classes were more likely to have used hookah than those in the Stable High or Rapid Escalator classes (χ2 (3) = 24.63, p < .001).

Table 3.

Percentage of Members in Each High School Trajectory Class and the Whole Sample Using Cigarettes Only, Hookah Only, Both, or Neither at Age 20/21, and the Association Between Cigarette and Hookah Use (Phi Coefficient)

| High school trajectory class (n) | Age 20/21 | Phi coefficient | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cigarettes only | Hookah only | Both | Neither | ||

| Nonsmokers (482) | 14% | 9% | 17% | 60% | 0.43* |

| Experimenters (104) | 25% | 8% | 43% | 24% | 0.36* |

| Rapid Increasers (57) | 60% | 3% | 32% | 5% | −0.04 |

| Stable High Smokers (41) | 54% | 0% | 41% | 5% | 0.19 |

| Whole sample (684) | 22% | 8% | 24% | 46% | 0.40* |

Note. Age 20/21 cigarette and hookah use defined as using more than once in the past year.

*p > .001.

At age 20/21, 31% of the Nonsmokers in high school had smoked cigarettes in the past year, and 26% had used hookah. There was a strong association between age 20/21 smoking and hookah use in this group, χ2 (1) = 89.86, p < .001. Among those who smoked cigarettes, 54% had also used hookah, and among those who used hookah, 65% had also smoked cigarettes. Among the Experimenters in high school, 68% had smoked cigarettes in the past year, and 50% had used hookah. Similar to the Nonsmokers, there was a strong association between age 20/21 cigarette and hookah use for this group, χ2 (1) = 13.38, p < .001. Among those who had smoked cigarettes in the past year, 62% had also used hookah, and among those who had used hookah in the past year, 85% had smoked cigarettes. Among Rapid Escalators, 91% smoked cigarettes at age 20/21 and 35% used hookah. In contrast to the Nonsmokers and Experimenters, the relation between cigarettes and hookah use in this group was not significant, χ2 (1) = 0.06, p > .05. Among cigarette smokers, only 35% had used hookah, whereas among hookah users nearly all (90%) had smoked cigarettes. At age 20/21, 95% of the Stable High Smokers had smoked cigarettes in the past year and 40% had used hookah. Similar to the Rapid Escalators, the relation between cigarette and hookah use was not significant, χ2 (1) = 1.47, p > .05. Among cigarette smokers, only 43% had used hookah, whereas among hookah users all (100%) had smoked cigarettes.

In sum, among those who did not smoke in high school or who only experimented (Nonsmokers and Experimenters), there was a strong positive association between hookah use and smoking at age 20/21. For those who were smoking almost daily by the end of high school (Rapid Escalators and Stable High Smokers), there was no association between smoking and hookah use at age 20/21.

DISCUSSION

Adolescence is the time when youth are most likely to start cigarette smoking, and even time-limited use during this vulnerable period can have serious consequences. Because sensation seeking develops during childhood, it could be used to identify at-risk children. The present study examined the prospective associations between the development of sensation seeking and smoking trajectories across high school.

The four trajectory classes identified here were broadly comparable with those found in previous studies across somewhat different time periods in youth (Abroms et al., 2005; Brook et al., 2010; Colder et al., 2001; Guo et al., 2002; Heron et al., 2011). The Stable High Smokers smoked almost daily on entry into high school and continued smoking at that level across high school. The Rapid Escalators started high school smoking very rarely and ended smoking at approximately the same level as the Stable High Smokers. The Experimenters were only smoking about a couple of times a year by the end of high school and the Stable Nonsmokers never or only very occasionally smoked in high school.

As hypothesized, both high initial and increasing levels of sensation seeking increased the odds of membership in any smoking class, and this was the case for both genders. These findings are an important extension of previous work (Crawford et al., 2003) because they demonstrate the significance of rate of growth of sensation seeking over childhood as well as level of sensation seeking for later cigarette smoking. Neither initial level nor slope of sensation seeking discriminated among the three trajectory classes for smokers indicating that the prior development of sensation seeking appears to influence whether or not youth are susceptible to initiating smoking either early (Stable High Smokers) or at any time during high school (Rapid Escalators and Experimenters). There were no gender differences in the effects of sensation seeking although in all contrasts girls were more likely to be in classes representing higher levels of smoking. Consistent with past research showing that parental SES is a risk factor for adolescent smoking, being on the free or reduced lunch program was a predictor in all contrasts (Soteriades & DiFranza, 2003).

Biological and social processes may account for the association between the development of childhood sensation seeking and membership in cigarette smoking trajectory classes in high school. This study found that the rate of increase in sensation seeking over childhood as well as the level predicted later smoking. Increasing sensation seeking suggests increasing neurological sensitivity to reward and corresponding motivation to use rewarding substances including nicotine (Roberti, 2004; Zuckerman, 1996). Increasing sensation seeking also has indirect influences on substance use via the development of social and cognitive mediators, such as the greater likelihood of affiliating with deviant peers and having more favorable social images of cigarette users (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Gerrard et al., 2006). The combination of these mechanisms suggests that children with higher levels and more rapid growth of sensation seeking are poised to pursue activities that provide novel and rewarding stimulation. High school offers numerous new opportunities for such activities, including associating with smoking peers (Donohew et al., 1999; Hampson, Andrews, & Barckley, 2008; Yanovitzky, 2005).

The present findings suggest that identifying children with increasing levels of sensation seeking, as well as those with high levels of sensation seeking, may be important for screening and intervention purposes. Intervening with children to deflect them from a path of escalating thrill seeking early in childhood may result in less smoking later. Alternatively, etiological factors predictive of initial levels growth in sensation seeking, such as early pubertal maturation, can be studied to identify those most at risk of future problem behaviors, including smoking. Future research should evaluate whether interventions to increase self-regulation also decelerate growth of sensation seeking in those children most at risk. Interventions to divert children from health-damaging to exciting but health-promoting activities may be particularly important for children with higher rates of increasing sensation seeking.

Smoking trajectories in youth offer a novel approach to predicting later consequences of adolescent smoking patterns, including use of alternative tobacco products. The investigation of the cooccurrence of smoking and hookah use at age 20/21 within each high school smoking trajectory class yielded an important finding. The association was strongest, and significant, for those who smoked the least in high school and was not significant for those who smoked the most. Among young hookah users, smoking hookah is perceived as less risky than smoking cigarettes (Smith et al., 2011), suggesting these hookah uses may consider themselves as “nonsmokers.” Although we do not know when previous nonsmokers initiated use of cigarettes or hookah, the finding that previous nonsmokers were more likely to smoke if they use hookah, suggests that hookah use may have preceded cigarette use and that hookah use could potentially serve as a gateway to the uptake of cigarette smoking (Primack et al., 2008).

Our findings must be seen in the light of a number of limitations. The recruitment rate at time 1 (50.7%) was less than desirable although fairly typical of epidemiological, community-based studies (Andrews et al., 2003), and the sample lacked ethnic diversity. The measure of sensation seeking exhibited only marginally acceptable internal reliability. These limitations may have underestimated the strength of the associations between sensation seeking and adolescent smoking. Although the development of sensation seeking preceded the assessment of smoking trajectories in time, the direction of causality cannot be inferred from this study. However, the prospective association between the prior development of sensation seeking and later cigarette use strengthens the argument that traits influence substance use development. The models tested in this study focused on relating the development of one personality trait to the later development of cigarette use, leaving out many other known risk factors. Evidence for the relevance of trait growth as well as level indicates that future testing of more complex models of influences on smoking development should include both these personality parameters.

In conclusion, these longitudinal findings demonstrate the significance of early development of sensation seeking for later trajectory classes of cigarette use and support calls for interventions in childhood. The importance of early childhood intervention is underscored by the probability that substance use and personality traits are likely to have reciprocal relations once substance use is initiated. Personality is least stable in childhood (Roberts & DelVecchio, 2000), making it an optimal period in which to promote the growth of self-control and reduce the growth of thrill seeking through school-based strategies directed at all students. Future research could employ a person-centered approach to derive classes consisting of trajectories of sensation seeking and link them to future smoking trajectories to identify those most at risk. Children identified as being most at risk (i.e., high on level and rate of growth of sensation seeking) could be targeted for additional intervention. An alternative strategy is to insure that universal smoking prevention interventions contain elements tailored for sensation seekers that are effective for these children at most risk (Andrews et al., 2011). Early intervention has the potential to deflect children from high-risk developmental paths leading to increasing substance use and its attendant negative consequences on life outcomes.

FUNDING

The work was supported by National Institute of Drug Abuse at the National Institutes of Health (R01 DA10767).

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Niraja Lorenz, Martha Hardwick, and the assessment staff for helping with data collection, and Christine Lorenz for manuscript preparation.

REFERENCES

- Abroms L., Simons-Morton B., Haynie D. L., Chen R. (2005). Psychosocial predictors of smoking trajectories during middle and high school. Addiction, 100, 852–861.10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01090.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I., Fishbein M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; [Google Scholar]

- Andrews J. A., Gordon J. S., Hampson S. E., Christiansen S. M., Gunn B., Slovic P., Severson H. H. (2011). Short-term efficacy of Click City®: Tobacco: Changing etiological mechanisms related to the onset of tobacco use. Prevention Science, 12, 89–102.10.1007/s11121-010-0192-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews J. A., Hampson S., Peterson M. (2011). Early adolescent cognitions as predictors of heavy alcohol use in high school. Addictive Behaviors, 36, 448–455.10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews J. A., Hampson S. E., Barckley M., Gerrard M., Gibbons F. X. (2008). The effect of early cognitions on cigarette and alcohol use in adolescence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 22, 96–106.10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews J. A., Tildesley E., Hops H., Duncan S. C., Severson H. (2003). Elementary school age children’s future intentions and use of substances. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 32, 556–567.10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook J. S., Balka E. B., Ning Y., Brook D. W. (2007). Trajectories of cigarette smoking among African Americans and Puerto Ricans from adolescence to young adulthood: Associations with dependence on alcohol and illegal drugs. The American Journal on Addictions, 16, 195–201.10.1080/10550490701375244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook D. W., Brook J. S., Zhang C., Whiteman M., Cohen P., Finch S. J. (2008). Developmental trajectories of cigarette smoking from adolescence to the early thirties: Personality and behavioral risk factors. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 10, 1283–1291.10.1080/14622200802238993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook J. S., Ning Y., Brook D. W. (2006). Personality risk factors associated with trajectories of tobacco use. The American Journal on Addictions, 15, 426–433.10.1080/10550490600996363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook D. W., Zhang C., Brook J. S., Finch S. J. (2010). Trajectories of cigarette smoking from adolescence to young adulthood as predictors of obesity in the mid-30s. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 12, 263–270.10.1093/ntr/ntp202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burk L. R., Armstrong J. M., Goldsmith H., Klein M. H., Strauman T. J., Costanzo P., Essex M. J. (2011). Sex, temperament, and family context: How the interaction of early factors differentially predict adolescent alcohol use and are mediated by proximal adolescent factors. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 25, 1–15.10.1037/a0022349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush P. J., Iannotti R. J. (1992). Elementary schoolchildren’s use of alcohol, cigarettes and marijuana and classmates’ attribution of socialization. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 30, 275–287.10.1016/0376-8716(92)90062-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L., Presson C. C., Pitts S. C., Sherman S. J. (2000). The natural history of cigarette smoking from adolescence to adulthood in a midwestern community sample: Multiple trajectories and their psychosocial correlates. Health Psychology, 19, 223–231.10.1037/0278-6133.19.3.223 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder C. R., Mehta P., Balanda K., Campbell R. T., Mayhew K., Stanton W. R., Flay B. R. (2001). Identifying trajectories of adolescent smoking: An application of latent growth mixture modeling. Health Psychology, 20, 127–135.10.1037/0278-6133.20.2.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford A. M., Pentz M. A., Chou C. P., Li C., Dwyer J. H. (2003). Parallel developmental trajectories of sensation seeking and regular substance use in adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 17, 179–192.10.1037/0893-164X.17.3.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster A. P., Laird N. M., Rubin D. B. (1977). Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, B, 39, 1–38 [Google Scholar]

- Donohew R. L., Hoyle R. H., Clayton R. R., Skinner W. F., Colon S. E., Rice R. E. (1999). Sensation seeking and drug use by adolescents and their friends: Models for marijuana and alcohol. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 60, 622–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran N., Khoddam R., Sanders P. E., Schweizer C., Trim R. S., Myers M. G. (2012). A prospective study of the acquired preparedness model: The effects of impulsivity and expectancies on smoking initiation in college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors,10.1037/a0028988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran N., Sanders P. E., Bekman N. M., Worley M. J., Monreal T. K., McGee E, … Brown S. A. (2011). Mediating influences of negative affect and risk perception on the relationship between sensation seeking and adolescent cigarette smoking. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 13, 457–465.10.1093/ntr/ntr025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eissenberg T., Shihadeh A. (2009). Waterpipe tobacco and cigarette smoking: Direct comparison of toxicant exposure. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37, 518–523.S0749-3797(09)00583-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankenberger K. D. (2004). Adolescent egocentrism, risk perceptions, and sensation seeking among smoking and nonsmoking youth. Journal of Adolescent Research, 19, 576–590.10.1177/0743558403260004 [Google Scholar]

- Gerrard M., Gibbons F. X., Brody G. H., Murry V. M., Wills T. A. (2006). A theory-based dual focus alcohol intervention for pre-adolescents: Social cognitions in The Strong African American Families Program. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 20, 185–195.10.1037/0893-164X.20.2.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J., Chung I., Hill K. G., Hawkins J., Catalano R. F., Abbott R. D. (2002). Developmental relationships between adolescent substance use and risky sexual behavior in young adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health, 31, 354–362.10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00402-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson S. E., Andrews J. A., Barckley M. (2007). Predictors of development of elementary-school children’s intentions to smoke cigarettes: Prototypes, subjective norms, and hostility. Nicotine and Tobacco Control, 9, 751–760.10.1080/14622200701397908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson S. E., Andrews J. A., Barckley M. (2008). Childhood predictors of adolescent marijuana use: Early sensation seeking, deviant peer affiliation and social images. Addictive Behaviors, 33, 1140–1147. 10.1016/ j.addbeh.2008.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson S. E., Andrews J. A., Barckley M., Severson H. H. (2006). Personality predictors of the development of elementary-school children’s intentions to drink alcohol: The mediating effects of attitudes and subjective norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 20, 288–297.10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden K., Tucker-Drob E. M. (2011). Individual differences in the development of sensation seeking and impulsivity during adolescence: Further evidence for a dual systems model. Developmental Psychology, 47, 739–746.10.1037/a0023279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron J., Hickman M., Macleod J., Munafò M. R. (2011). Characterizing patterns of smoking initiation in adolescence: Comparison of methods for dealing with missing data. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 13, 1266–1275.10.1093/ntr/ntr161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hix-Small H., Duncan T. E., Duncan S. C., Okut H. (2004). A multivariate associative finite growth mixture modeling approach examining adolescent alcohol and marijuana use. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26, 255–269.10.1023/B:JOBA.0000045341.56296.fa [Google Scholar]

- Johnston L. D., O’Malley P. M., Bachman J. G., Schulenberg J. E. (2012). Monitoring the future: National results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2011 Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; [Google Scholar]

- Klimstra T. A., Akse J., Hale W., Raaijmakers Q. W., Meeus W. J. (2010). Longitudinal associations between personality traits and problem behavior symptoms in adolescence. Journal Of Research In Personality, 44(2), 273–284. 10.1016/j.jrp.2010.02.004 [Google Scholar]

- Kraft P., Rise R. (1994). The relationship between sensation seeking and smoking, alcohol consumption and sexual behavior among Norwegian adolescents. Health Education Research, 9, 193–200.10.1093/her/9.2.193 [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B. O. (1991). Analysis of longitudinal data sets using latent variable models with varying parameters. In Collins L. M., Horn J. L. (Eds.), Best methods for the analysis of change: Recent advances, unanswered questions, future directions (pp. 1–17). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B., Muthén L. (2000). Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: Growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 24, 882–891.10.1111/ j.1530-0277.2000.tb02070.x [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L. K., Muthén B. O. (1998/2009). Mplus user’s guide Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; [Google Scholar]

- Nagin D. S. (2005). Group-based modeling of development Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb M. D., McGee L. (1991). Influence of sensation seeking on general deviance and specific problem behaviors from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 614–628.10.1037/0022-3514.61.4.614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylund K. L., Asparouhov T., Muthén B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling, 14, 535–569 [Google Scholar]

- Orlando M., Tucker J. S., Ellickson P. L., Klein D. J. (2005). Concurrent use of alcohol and cigarettes from adolescence to young adulthood: An examination of developmental trajectories and outcomes. Substance Use & Misuse, 40, 1051–1069.10.1081/JA-200030789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins K. A., Lerman C., Coddington S. B., Jetton C., Karelitz J. L., Scott J. A., Wilson A. S. (2008). Initial nicotine sensitivity in humans as a function of impulsivity. Psychopharmacology, 200, 529–544.10.1007/s00213-008-1231-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primack B. A., Shensa A., Kim K. H., Carroll M. V., Hoban M. T., Leino E. V, … Fine M. J. (2012). Waterpipe smoking among U.S. university students. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 15(1), 29–35.10.1093/ntr/nts076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primack B. A., Sidani J., Agarwal A. A., Shadel W. G., Donny E. C., Eissenberg T. E. (2008). Prevalence of and associations with waterpipe tobacco smoking among U.S. university students. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 36(1), 81–86. 10.1007/s12160-008-9047-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberti J. W. (2004). A review of behavioral and biological correlates of sensation seeking. Journal of Research in Personality, 38, 256–279 [Google Scholar]

- Roberts B. W., DelVecchio W. F. (2000). The rank-order consistency of personality traits from childhood to old age: A quantitative review of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 3–25.10.1037/0033-2909.126.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo M. F., Stokes G. S., Lahey B. B., Christ M. A. G., McBurnett K., Loeber R, … Green S. M. (1993). A sensation seeking scale for children: Further refinement and psychometric development. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 15, 69–86.10.1007/BF00960609 [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. R, Novotny T. E, Edland S. D, Hofstetter C., Lindsay S. P, Al-Delaimy W. K. (2011). Determinants of hookah use among high school students. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 13(7), 565–572. 10.1093/ntr/ntr041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soteriades E. S., DiFranza J. R. (2003). Parent’s socioeconomic status, adolescents’ disposable income, and adolescents’ smoking status in Massachusetts. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 1155–1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L., Albert D., Cauffman E., Banich M., Graham S., Woolard J. (2008). Age differences in sensation seeking and impulsivity as indexed by behavior and self-report: Evidence for a dual systems model. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1764–1768.10.1037/a0012955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson M. T., Hoyle R. H., Palmgreen P., Slater M. D. (2003). Brief measures of sensation seeking for screening and large-scale surveys. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 72, 279–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterling K. L., Mermelstein R. (2011). Examining hookah smoking among a cohort of adolescent ever smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 13, 1202–1209.10.1093/ntr/ntr146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutfin E. L., McCoy T. P., Reboussin B. A., Wagoner K. G., Spangler J., Wolfson M. (2011). Prevalence and correlates of waterpipe tobacco smoking by college students in North Carolina. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 115, 131–136.10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.01.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarter R. E., Vanyukov M. (1994). Alcoholism: A developmental disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 1096–1107.10.1037/0022-006X.62.6.1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White H., Pandina R. J., Chen P. (2002). Developmental trajectories of cigarette use from early adolescence into young adulthood. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 65, 167–178.10.1016/S0376-8716(01)00159-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills T. A., Vaccaro D., McNamara G. (1994). Novelty seeking, risk taking, and related constructs as predictors of adolescent substance use: An application of Cloninger’s theory. Journal of Substance Abuse, 6, 1–20.10.1016/S0899-3289(94)90039-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills T. A., Windle M., Cleary S. D. (1998). Temperament and novelty seeking in adolescent substance use: Convergence of dimensions of temperament with constructs from Cloninger’s theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 387–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanovitzky I. (2005). Sensation seeking and adolescent drug use: The mediating role of association with deviant peers and pro-drug discussions. Health Communication, 17, 67–89.10.1207/s15327027hc1701_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker R. A., Donovan J. E., Masten A. S., Mattson M. E., Moss H. B. (2008). Early developmental processes and the continuity of risk for underage drinking and problem drinking. Pediatrics, 121(Suppl. 4), S252–S272.10.1542/peds.2007-2243B [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. (1996). The psychobiological model for impulsive unsocialized sensation seeking: A comparative approach. Neuropsychobiology, 34, 125–129.10.1159/000119303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M., Ball S., Black J. (1990). Influences of sensation seeking, gender, risk appraisal, and situational motivation on smoking. Addictive Behaviors, 15, 209–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M., Eysenck S., Eysenck H. J. (1978). Sensation seeking in England and America: Cross-cultural, age, and sex comparisons. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 46, 139–149.10.1037/0022-006X.46.1.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]