Abstract

Introduction:

To address the lack of smoking cessation programs available to young adults, Stop My Smoking (SMS) USA, a text messaging–based smoking cessation program, was developed and pilot tested.

Methods:

This was a two-arm randomized controlled trial with adaptive randomization (arms were balanced by sex and smoking level [heavy vs. light]), conducted nationally in the United States. One hundred sixty-four 18- to 25-year-old daily smokers who were seriously thinking about quitting in the next 30 days were randomized to either (a) the 6-week SMS USA intervention (n = 101) or (b) an attention-matched control group aimed at improving sleep and physical activity (n = 63). The main outcome measure was 3-month continuous abstinence, verified by a significant other. Participants but not researchers were blinded to study arm allocation.

Results:

Based upon intent-to-treat analyses, intervention participants (39%) were significantly more likely than control participants (21%) to have quit at 4 weeks postquit (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 3.33, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.48, 7.45). Findings were not sustained at 3 months postquit, although rates in the SMS USA group were favored (40% vs. 30%, respectively; aOR = 1.59, 95% CI: 0.78, 3.21). Subsequent analyses suggested that among intervention participants, SMS USA might be more influential for youth not currently enrolled in a higher education (p = .06).

Conclusions:

Consistent with pilot studies, the sample was underpowered. Data suggest, however, that the SMS USA program affects smoking cessation rates at 4 weeks postquit. More research is needed before conclusions can be made about long-term impact. Identifying profiles of users for whom the program may be particularly beneficial also will be important.

INTRODUCTION

An estimated 22%–34% of 18-to 24-year olds in the United States currently smoke cigarettes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2011), which is higher than any other age group (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012). More than a half report a desire to quit or cut down (Lamkin, Davis, & Kamen, 1998; Reeder, Williams, McGee, & Poulton, 2001; Stone & Kristeller, 1992), yet few are successful (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1993, 2002). This may in part be because there is a clear lack of intervention programs that are targeted and accessible to young adults (Murphy-Hoefer et al., 2005). Accordingly, very few evaluation studies of young adult cessation programs have been conducted (Bader, Travis, & Skinner, 2007; Lantz, 2003; Murphy-Hoefer et al., 2005), especially among those who are not enrolled in a college or university. This is particularly critical given that smoking rates are highest among adults without a college degree (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010; Green et al., 2007; Solberg, Asche, Boyle, McCarty, & Thoele, 2007).

To invigorate cessation rates, cessation programs must be available where young adults “are.” More and more, this translates to modalities such as text messaging: 95% of U.S. young adults have a cell phone of which 97% use text messaging (Smith, 2011). Emerging evidence supports the efficacy of text messaging–based smoking cessation programs (Free et al., 2011; Rodgers et al., 2005; Whittaker et al., 2009). Following promising, biochemically verified, short-term cessation outcomes by Rodgers and colleagues (2005) in New Zealand, a recent trial conducted in the United Kingdom among 5,800 adults reports that “txt2stop” users are more than twice as likely to have quit (as confirmed by biochemical verification) at 6 months compared with control participants who received one text message per week, reminding them that they were in the study (Free et al., 2011).

Stop My Smoking (SMS) USA is a text messaging–based smoking cessation program tailored to the experiences of young adult smokers. Special efforts are made to reach youth both in and outside of higher education settings and to ensure a racially and economically diverse sample. Formative development activities are reported elsewhere (Ybarra, Prescott, & Holtrop, 2012). Here, we report findings from the pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT). As one of the first smoking cessation programs developed and tested in a diverse sample of young adults, findings inform public health efforts to reduce smoking in this underserved population of smokers.

METHODS

This was a two-arm RCT with adaptive randomization that balanced study arms by sex and smoking levels (heavy vs. light) conducted in the United States. The research protocol was approved by Chesapeake IRB (ClinicalTrials.gov ID# NCT01516632).

Participants

Participants were recruited nationally through online advertisements (e.g., Craigslist) between May 3, 2011 and August 4, 2011. Eligibility criteria included the following: being between the ages of 18–25, able to read and write in English, owning a cell phone, being cognizant of how to send and receive text messages, being currently enrolled or intending to enroll in an unlimited text messaging plan, smoking 24 cigarettes or more per week (at least four per day on at least 6 days/week) (Obermayer, Riley, Asif, & Jean-Mary, 2004), seriously thinking about quitting in the next 30 days, and agreeing to smoking cessation status verification by a significant other (e.g., family member, friend).

Intervention and Control Groups

Intervention group participants were exposed to a 6-week cessation program. Content was tailored based upon where in the quitting process participants were: All participants received 2 weeks of Pre-Quit messages aimed at encouraging them to clarify reasons for quitting and to understand their smoking patterns and tempting situations/triggers/urges. Early Quit messages, sent on Quit Day and through the first week postquit, talked about common difficulties and discomforts associated with quitting and emphasized the use of coping strategies. Late Quit messages encouraged participants to recognize relapse in a different way (e.g., situations, confidence) and provided actionable information about how to deal with issues that arise as a nonsmoker (e.g., stress, moods).

Based on telephone quitline research that suggests most smoking relapse occurs within the first week (Zhu et al., 1996), intervention participants received a text message at Post-Quit Day 2 and 7 that asked their smoking status. At either time point, if participants reported smoking, they were pathed to Relapse messages that focused on helping them get back on track and to recommit to quitting. If participants were smoking at both days, they were pathed to an Encouragement arm that focused on norms for quitting and suggested that participants try quitting again at later time.

Participants received four messages per day during the 2-week Pre-Quit stage, with the exception of Day 1 and Day 14 when they received five and six messages, respectively. In the Early Quit stage, participants received nine messages on both Quit Day and Post-Quit Day 2, eight messages on the third day, and then one fewer message each day until the last day of the week when four messages were received. In Late Quit, participants received two messages per day for 2 weeks and then one message per day during the final week. Participants in Relapse received two messages per day; those in Encouragement received one message per day for 4 days.

Intervention group participants had access to two program components first used in the STOMP NZ program (Rodgers et al., 2005): (a) Text Buddy (another person in the program that a participant was assigned to so they could text one another for support anonymously during the program; assignment was sequential so that buddies would be in similar stages during the quitting process); (b) Text Crave (immediate, on-demand messages aimed at helping the participant through a craving). A project Web site (StopMySmoking.com) provided additional quitting resources, technical support, and a discussion forum.

Control group participants received a text-messaging program that was similar to the intervention program on the number of text messages received per day across the 6 weeks. For example, both intervention and control participants received nine messages on their Quit Day and the day after, but control group messages did not mention that it was the participant’s quit day. Message content was aimed at improving one’s sleep and exercise habits within the context of how it would help the participant quit smoking. Messages were not tailored based on quitting stage (e.g., Pre-Quit vs. Early Quit) nor were Text Buddy and Text Crave components available to this group. Examples of intervention and control messages are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Example Text Messages for the Intervention and Control Groups

| Day sent | Intervention group messages | Control group messages |

|---|---|---|

| Day 1(Pre-Quit)a | Congratulations! The hardest part—deciding to quit—is already behind you. Write down your quit date (insert day) and post it where you can see it every day. | Hi there! Welcome to the SMS USA project. We’re happy you’re here. We look forward to working with you! |

| Day 1(Pre-Quit) | The SMS USA program is like a recipe book to help you quit smoking. Not every text will work for you, but try each one before you judge—just to see! | These next several weeks we’re going to be working with you to improve your sleep and physical activity. Why? Because both will help you to quit smoking. |

| Day 2(Pre-Quit) | Write down a list of reasons why you want to quit smoking. Put the list in a place where you’ll see it every day. | How much sleep are you getting? Keep a log for the next week. Note when you go to bed, wake up; Have trouble going to sleep? Wake up in the middle of the night? |

| Day 2(Pre-Quit) | Want to connect with other people quitting in the SMS USA program? Hear about how they are getting ready to quit? Go to www.stopmysmoking/discuss | The Centers for Disease Control recommends adults get 30min of physical activity at least 5 days/week. Sound hard? Relax. We’ll figure it out together. |

| Day 3(Pre-Quit) | Got stress? Maybe it’s your cigarettes. In between cigarettes, your body goes through nicotine withdrawal and makes you feel stressed out and anxious. | Sleeping and exercising go hand-in-hand when you’re trying to quit smoking. You have more energy, you sleep better, and it gives you the strength to quit. |

| Day 15(Quit Day) | I bet you’re feeling cranky and annoyed right now. This is all normal. Just take a deep breath and get through the next 5min. | Each time you meet a sleep or physical activity goal, no matter how small, be sure to give yourself a reward. |

| Day 20(Early Quit) | Right now, you’re learning to quit. Just like learning to ride a bike or drive a car, it takes time. Before you know it, you’ll learn to be a nonsmoker too. | Quitting smoking is hard work. Sleeping well can help your body prepare for quitting physically and emotionally. |

| Day 31(Late Quit) | Encouragement from your friends and family might be starting to wane about now, but remember that they are probably still proud of you for quitting. | Regular exercise has a lot of benefits: Better sleep and relief from stress are just a couple. Remind yourself of YOUR reasons to make these life changes. |

Note. aExamples are mirror messages sent to the intervention and control groups, taken from five text messages each on Days 1–3, nine on Day 15, five on Day 15, and two on Day 31.

Outcomes

Survey data were collected online for the baseline survey, via text message at 4 weeks postquit, and a combination of text and online for the 3-month postquit follow-up. No changes to prespecified outcomes were made after the trial commenced.

Primary outcome: Three-month continuous abstinence. In accordance with the NIH Behavior Change Consortium recommendations (Williams, McGregor, Borrelli, Jordan, & Strecher, 2005), participants were categorized as quit if they reported smoking five or fewer cigarettes since their quit date. Based on standard outcome criteria proposed by West, Hajek, Stead, and Stapleton (2005), continuous abstinence was measured with the following question: “Have you smoked at all, even just a puff, since your quit date?” Response options were as follows: (a) No, not a puff; (b) One to five cigarettes; or (c) More than five cigarettes. Continuous abstinence was verified by phone contact with a significant other (Emont, Collins, & Zywiak, 1991; Ossip-Klein et al., 1991; Shumaker & Grunberg, 1986). Biochemical verification was not collected given the low risk that such verification would change the interpretation of results in this minimal contact intervention (Williams et al., 2005).

Secondary outcomes included smoking five or fewer cigarettes since quit day at 4 weeks postquit verified by a significant other and 7-day point prevalence abstinence at 4 weeks. Additionally, measures of acceptability (e.g., participant rating of frequency and timing of messages; dropout rates) were collected at the 3-month assessment.

Demographic and Cell Phone Characteristics

At baseline, participants provided their age, sex, income, race, ethnicity, educational attainment, current employment status, the average number of text messages spent per week, and the length of ownership of a cell phone.

Smoking Behavior

Participants provided information about their smoking history at baseline (e.g., age of first cigarette). In accordance with procedures implemented by the National Study of Drug Use and Health (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2004), level of tobacco dependence was measured using one item from the Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence scale (i.e., report of smoking one’s cigarette within 30min of waking up on the days that he or she smoked) or a score of 2.75 or greater on the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale.

Quitting Characteristics

At baseline, participants reported on a scale of 0–10 how important quitting was to them and how confident they were that they would be able to quit (Miller, Zweben, DiClemente, & Rychtarik, 1992). Participants also reported ever and past-year quit attempts that lasted for 24hr or longer and whether or not they ever had, as well as in the SMS USA study, planned to use an evidence-based quitting aid (i.e., pharmacotherapy, individual therapy, or group therapy).

Psychosocial Characteristics

A lack of self-efficacy may be related to one giving up easily and abandoning one’s coping strategies during the quitting process (Bandura, 1997). Resistance self-efficacy was measured at baseline using the four-item scale developed by Lawrance and Rubinson (1986). Internal consistency was acceptable (Cronbach’s alpha = .77). Social support, another important factor related to quitting (May & West, 2000), was measured using the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet, & Farley, 1988). Acceptable internal consistency of three subscales (family, friends, and a “special person”) was observed (Cronbach’s alpha from .88 to .94). Depressive symptomatology was measured using nine items from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Eaton, Muntaner, Smith, Tien, & Ybarra, 2004). Responses were captured on the PHQ’s (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001) four-point Likert scale. The scale demonstrated acceptable internal validity (Cronbach’s alpha = .87). Concurrent risky drinking is associated with reduced likelihood of smoking cessation (Sher, Gotham, Erickson, & Wood, 1996). Participants who reported at least two of the four CAGE (Dhalla & Kopec, 2007) risky drinking-related behaviors were coded as risky drinkers.

Sample Size

In this feasibility trial, our sample size calculation was based on estimating the parameters within 8% of their actual values in the population with 95% confidence. Although we did not calculate the sample size to have statistical power a priori to detect effects that we would consider as clinically meaningful, the post-hoc power to detect the observed effect (10% difference in abstinence, i.e., 30% vs. 40%) in the current design using logistic regression was .25 with alpha of .05.

Randomization and Masking

Participants were randomly assigned to the intervention or control arm using a computerized adaptive randomization program (Taves, 1974) that minimized the likelihood of imbalance between the study arms with respect to biological sex and intensity of smoking (i.e., heavy smoker [≥20 cigarettes per day]) while maintaining a ratio of 2:1 in the intervention:control groups. Participants were assigned at a higher ratio to the intervention to increase the amount of information obtained about the intervention experience. Participants, but not researchers, were blind to arm allocation.

Ongoing monitoring of the arm allocations revealed an imbalance in the minimum number of participants intended for each study arm within each subgroup (e.g., male heavy smokers). As a result, allocation concealment was broken for the last eight participants enrolled. To rectify the imbalance, these participants were manually assigned to the arm subgroup that required additional participants to become balanced. For example, the control group had fewer male light smokers than it should have; as such, all seven male light smokers in the queue were assigned to the control group. The proportion of participants in each subgroup designed to balance the study arms were maintained for both arms.

Procedures

Smokers expressed their interest by completing an online screener form, which was then e-mailed to the project coordinator. Eligible candidates were contacted by the project coordinator, who scheduled an appointment over the phone to confirm eligibility, explain study details, obtain verbal consent, and complete the registration process. All participants, irrespective of study arm, identified a quit day that was at least 15 days but no more than 30 days from their registration date. Those who smoked 10 cigarettes or more per day were counseled to consider pharmacotherapy to assist in their quitting (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2009). After registration, participants were e-mailed an online survey link and instructed to complete the survey as soon as possible. The baseline survey had to be completed in order to receive text messages.

Both control and intervention messages began 14 days prior to one’s quit date. Participants received incentives of $10 and $20 after completing the 4-week and 3-month postquit follow-ups, respectively. A third of participants received an additional $10 if they responded within 48hr, another third of participants received $10 if they completed the online survey within 48hr of receiving a second reminder text, and a different third received $10 if they completed a minisurvey via text messaging at 3 months. Participants could opt-out of the study at any time by texting “end” to the program or by contacting project staff.

Data Cleaning

Nonresponsive (i.e., “decline to answer”) responses to self-report instruments included in the analyses were imputed using best-set regression (StataCorp, 2009). All variables had less than 5% of data imputed. A variable reflecting the number of imputed variables for each participant was included in all multivariate models to adjust for the impact that imputation may have had on the results.

Statistical Analyses

Baseline characteristics of participants were compared by the study arm using chi-square or t tests depending on the measurement’s scale. Logistic regression models were used to estimate the odds of quitting for the intervention versus control groups. Analyses were conducted in two ways: intent-to-treat (ITT) such that all randomized individuals were included in the analysis (all participants lost to follow-up were assumed to still be smoking) and per-protocol analysis such that only those who completed the follow-up measures were included in the analysis. Models were adjusted for additional factors that may influence smoking outcomes in this population (denoted as “aOR” for adjusted odds ratio). Because of their influence on cessation rates (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2001; Nordstrom et al., 2000), biological sex and baseline intensity of smoking were examined as effect modifiers. Given the study’s outreach focus to enroll young adults outside of higher education settings and those of minority race, these characteristics also were tested for effect modification.

RESULTS

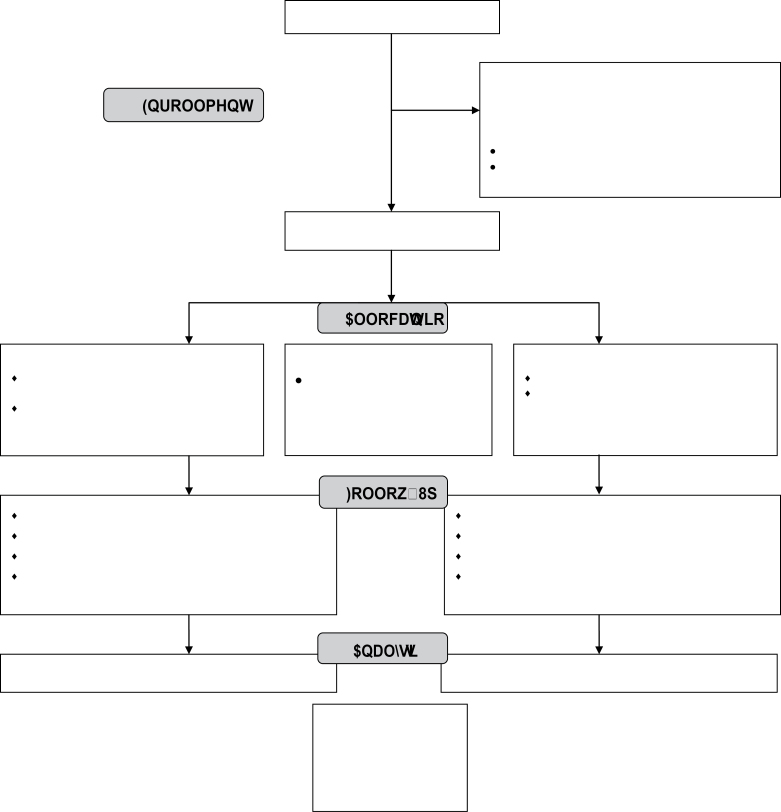

As shown in Figure 1, 1,916 people expressed interest in participating, 585 (31%) of whom appeared eligible based upon the online screener form. Of these 585, contact was not made with 49% (n = 284). Fifteen percent (n = 90) declined to participate: reasons included the incentives being too low and not having enough time to engage with the program. Seventy percent of eligible participants (n = 211) consented to participate and were randomized into the study. Forty seven of these participants did not complete the online baseline survey and therefore did not begin receiving text messages. The software program did not retain the randomization assignment of participants who did not begin to receive text messages. The randomization assignment of these 47 participants could not be recovered, precluding their inclusion in the ITT analyses. Thus, the final sample size (i.e., the number of participants randomized and received at least one program message) was n = 164: 101 in the intervention and 63 in the control groups. Of the 1,331 ineligible participants, not seriously thinking about quitting in the next 30 days was the most common reason (see Table A1).

Figure 1.

Stop My Smoking USA randomized controlled trial consort diagram.

Four-week follow-up was conducted between April and June; and 3-month follow-up between June and August, 2011. Eighty-seven percent of participants responded at 4 weeks postquit and 80% at 3 months postquit. Differential follow-up between the intervention and control groups was not observed at either 4 weeks (86% vs. 87%, respectively; p = .83) or 3 months (80% vs. 80%, respectively; p = .91) follow-up. Five intervention participants actively withdrew from the program. No control participants withdrew.

Baseline Data

A summary of baseline participant characteristics by study arm is shown in Table 2. Characteristics were statistically similar across the two groups except for employment status. Smoking behavior and psychosocial characteristics were similar.

Table 2.

Summary Statistics for the Baseline Characteristics by the Study Arm

| Participants demographic and other characteristics at baseline | Control (n = 63)% (n) | Intervention (n = 101)% (n) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M, SD: Range: 18–25) | 21.6 (2.1) | 21.6 (2.1) | .82 |

| Female | 44.4 (28) | 43.6 (44) | .91 |

| Low income (<$35,000 vs. higher) | 90.5 (57) | 84.2 (85) | .25 |

| Married/living with someone | 27.0 (17) | 28.7 (29) | .81 |

| Race | .95 | ||

| White or Caucasian | 65.1 (41) | 64.4 (65) | |

| Black or African American | 14.3 (9) | 12.9 (13) | |

| Mixed racial background | 12.7 (8) | 15.9 (16) | |

| Others | 7.9 (5) | 6.9 (7) | |

| Ethnicity (Hispanic) | 12.7 (8) | 21.8 (22) | .14 |

| Current employment status | .04 | ||

| Not working | 55.6 (35) | 35.6 (36) | |

| Working ≤ 30 hr | 19.1 (12) | 23.8 (24) | |

| Working > 30 hr | 25.4 (16) | 40.6 (41) | |

| Currently enrolled in college, university, or junior college | 39.7 (25) | 42.6 (43) | .72 |

| Tenure with current cell phone number (months): M (SD) | 46.4 (31.6) | 44.8 (28.2) | .74 |

| Number of text messages sent on an average day: Median (25%, 75% quartile) | 45 (20, 100) | 50 (20, 100) | .24 |

| Number of text messages received on an average day: Median (25%, 75% quartile) | 50 (18, 100) | 60 (20, 100) | .17 |

| Smoking behavior | |||

| Average number of cigarettes smoked per day (M, SD; Range: 4–30) | 11.9 (5.7) | 12.4 (6.3) | .62 |

| Age at first cigarette (M, SD; Range: 4–23) | 14.4 (3.4) | 13.9 (3.2) | .29 |

| Number of years smoked cigarettes (Range: <1 year–5+ years) | 7.1 (3.5) | 7.7 (3.8) | .29 |

| Number of other smokers in the household (Range: 0–6) | 2.2 (1.3) | 2.0 (1.2) | .30 |

| Nicotine dependent | 93.7 (59) | 89.1 (90) | .33 |

| Importance of quitting to self (M, SD; Range: 1–10) | 8.9 (1.3) | 8.7 (1.5) | .53 |

| Confidence in one’s ability to quit (M, SD; Range: 0–10) | 6.5 (2.6) | 6.7 (2.2) | .60 |

| Number of quit attempts (ever) (Range: 0–5+ times) | 3.6 (1.7) | 3.7 (1.6) | .87 |

| Number of quit attempts in the past year (M, SD; Range: 0–5+) | 1.8 (1.7) | 1.5 (1.3) | .32 |

| Planning on using an evidence-based quitting aid for the current quit attempt | 17.5 (11) | 25.7 (26) | .22 |

| Ever used an evidence-based quitting aid before | 25.4 (16) | 30.7 (31) | .47 |

| Chantix, Zyban, or nicotine replacement therapy | 15.9 (10) | 22.8 (23) | .28 |

| Quit line | 6.4 (4) | 5.0 (5) | .70 |

| Individual or group therapy | 3.2 (2) | 4.0 (4) | .79 |

| Psychosocial characteristics | |||

| Resistance self-efficacy (M, SD; Range: 4–20) | 10.5 (4.0) | 10.6 (4.0) | .85 |

| Social support from a “special person” (M, SD; Range: 4–20) | 16.3 (3.9) | 15.1 (5.4) | .12 |

| Social support from family (M, SD; Range: 4–20) | 15.9 (3.6) | 15.3 (4.3) | .38 |

| Social support from friends (M, SD; Range: 4–20) | 16.6 (3.1) | 16.1 (4.0) | .42 |

| Depressive symptomatology (M, SD; Range: 0–27) | 9.3 (6.4) | 7.8 (6.2) | .14 |

| Risky drinking | 19.1 (12) | 32.7 (33) | .06 |

Note. Bold text denotes statistically significant differences at α = .05.

Smoking Cessation Outcomes

One-hundred and one participants randomized to the intervention and 63 randomized to the control group were included in the analyses. Based on ITT analysis, 40% of the participants in the intervention arm had a verified quit status compared with 30% in the control arm at 3 months postquit. The observed difference was not statistically significant (OR = 1.62, 95% CI: 0.82, 3.21). The intervention arm continued to be favored, although not significantly, after adjusting for biological sex, the level of smoking at baseline, employment status, and intention to use a quitting aid (aOR = 1.59, 95% CI: 0.78, 3.21). When data were assessed per protocol, findings were similar (aOR = 1.64, 95% CI: 0.77, 3.50). Harm was not reported by any participant in either group.

Participants in the intervention were significantly more likely to have quit at 4 weeks postquit (39%) than those in the control group (21%; aOR = 3.33, 95% CI: 1.48, 7.45); this was true also for 7-day point prevalence (44% vs. 27%; aOR = 2.55, 95% CI: 1.22, 5.30). Findings were similar when quit rates were assessed per protocol.

Investigation of Cessation Results by Important Subpopulations

The intervention appeared to be helpful for men (44% intervention vs. 29% control had quit at 3 months; p = .14), young adults not currently enrolled in higher education settings (45% vs. 26% control had quit at 3 months; p = .07), and participants of non-White race (42% intervention vs. 23% control had quit at 3 months; p = .14). Further examination of potential effect modification by biological sex, smoking intensity, and minority race did not reveal significant interactions between any of these characteristics and arm assignment. On the other hand, results suggested that enrollment in higher education settings was an effect modifier within the context of other potentially influential characteristics (arm assignment × school status; aOR = 4.7, 95% CI: 1.01, 22.3). The intervention appeared to be more influential for intervention participants not enrolled in higher education compared with control participants not enrolled in higher education (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Intent to Treat–Based Multivariable Model of the Relative Odds of Verified Quit Status at 3 Months Postquit Day (n = 164)

| Personal characteristics | aOR (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Arm assignment × school status | ||

| Control group, not in higher education | 1.0 (reference group) | |

| Control group, in higher education | 2.3 (0.7, 7.9) | .20 |

| Intervention group, not in higher education | 2.7 (1.0, 7.4) | .06 |

| Intervention group, in higher education | 1.3 (0.4, 3.7) | .66 |

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Non-White race | 0.7 (0.3, 1.6) | .44 |

| Male sex | 1.1 (0.5, 2.3) | .82 |

| Employment status | ||

| Not employed | 1.0 (reference group) | |

| ≤30hr per week | 0.7 (0.3, 2.0) | .54 |

| >30hr per week | 1.4 (0.6, 3.3) | .39 |

| Smoking characteristics | ||

| Nicotine dependent | 1.2 (0.3, 4.3) | .79 |

| Heavy smoking (>20 cigarettes per day) | 0.8 (0.3, 2.0) | .59 |

| Planning to use a quitting aid | 1.0 (0.4, 2.3) | .92 |

| Psychosocial characteristics | ||

| Quitting self-efficacy | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) | .47 |

| Depressive symptomatology | 1.0 (0.9, 1.0) | .58 |

| Anticipates poor support to quit from (or does not have any): | ||

| Friends | 0.4 (0.1, 1.4) | .16 |

| People one lives with | 1.6 (0.6, 4.3) | .33 |

| Social support | ||

| Special person | 0.8 (0.8, 0.9) | <.004 |

| Family | 1.1 (1.0, 1.3) | .06 |

| Friends | 1.0 (0.9, 1.2) | .91 |

| Risky drinking | 0.7 (0.3, 1.6) | .39 |

| Number of variables with imputed values | 1.1 (1.0, 1.2) | .04 |

Notes. Bold text denotes statistically significant differences at α = .05; aOR = adjusted odds ratio, ORs adjusted for all other variables shown above; CI = confidence interval.

Smoking Behavior Among Those Who Continue to Smoke

Among the 104 participants who reported smoking since their quit day, 30% of intervention and 20% of control participants reported not smoking—even a puff—in the past 7 days at 3-month follow-up (p = .52). Among the 93 participants who reported smoking at least one cigarette in the past 28 days at 3-month follow-up, those in the intervention reported reducing their average daily intake by 6.7 cigarettes (SD = 8.3) and the control group by 5.9 cigarettes (SD = 4.5; p = .60).

Program Acceptability

Indicators of program acceptability are shown in Table 4. Few participants said that the program disrupted their daily schedule (10% of intervention and 6% of control participants) or that they received too many messages (23% and 12%, respectively). About three in four in both groups (82% and 74%, respectively) agreed that they were likely to recommend the program to others.

Table 4.

Program Evaluation by Study Arm Among 3-Month Respondents (n = 129)

| Program evaluation | Control (n = 49)% (n) | Intervention (n = 80)% (n) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Made it easier to quit smoking | .04 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 10% (5) | 8% (6) | |

| Somewhat disagree | 14% (7) | 9% (7) | |

| Neither disagree nor agree | 33% (16) | 14% (11) | |

| Somewhat agree | 27% (13) | 44% (35) | |

| Strongly agree | 16% (8) | 26% (21) | |

| Disrupted my schedule | .75 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 57% (28) | 59% (47) | |

| Somewhat disagree | 20% (10) | 14% (11) | |

| Neither disagree nor agree | 16% (8) | 18% (14) | |

| Somewhat agree | 4% (2) | 9% (7) | |

| Strongly agree | 2% (1) | 1% (1) | |

| Received too many messages | .45 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 35% (17) | 25% (20) | |

| Somewhat disagree | 24% (12) | 29% (23) | |

| Neither disagree nor agree | 29% (14) | 24% (19) | |

| Somewhat agree | 10% (5) | 15% (12) | |

| Strongly agree | 2% (1) | 8% (6) | |

| Messages were easy to understand | .73 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 2% (1) | 3% (2) | |

| Somewhat disagree | 0% (0) | 1% (1) | |

| Neither disagree nor agree | 4% (2) | 1% (1) | |

| Somewhat agree | 12% (6) | 16% (13) | |

| Strongly agree | 82% (40) | 79% (63) | |

| Messages talked about what I was feeling and experiencing | .54 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 8% (4) | 4% (3) | |

| Somewhat disagree | 8% (4) | 4% (3) | |

| Neither disagree nor agree | 14% (7) | 18% (14) | |

| Somewhat agree | 43% (21) | 40% (32) | |

| Strongly agree | 27% (13) | 35% (28) | |

| I stopped reading the messages by the end of the program | .68 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 37% (18) | 35% (28) | |

| Somewhat disagree | 31% (15) | 23% (18) | |

| Neither disagree nor agree | 12% (6) | 14% (11) | |

| Somewhat agree | 10% (5) | 19% (15) | |

| Strongly agree | 10% (5) | 10% (8) | |

| The message tone was positive and made me feel supported | .10 | ||

| Strongly disagree | 2% (1) | 1% (1) | |

| Somewhat disagree | 10% (5) | 1% (1) | |

| Neither disagree nor agree | 10% (5) | 5% (4) | |

| Somewhat agree | 33% (16) | 33% (26) | |

| Strongly agree | 45% (22) | 60% (48) | |

| Likelihood of recommending program to others | .49 | ||

| Very unlikely | 4% (2) | 3% (2) | |

| Somewhat unlikely | 6% (3) | 6% (5) | |

| Neither | 16% (8) | 9% (7) | |

| Somewhat likely | 37% (18) | 31% (25) | |

| Very likely | 37% (18) | 51% (41) |

Note. Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Appraisal of the Text Buddy among intervention participants is shown in Table 5. About half (51%) of intervention participants contacted their Text Buddy at least once. Usage was highly skewed and ranged between 1 and 51 messages (M = 6.5, SD = 11.0). Users and nonusers were similar by participant sex, age, smoking intensity, and school status. Intervention participants who rated their Text Buddy as helpful were more likely to have quit at 3 months than participants who rated their Text Buddy otherwise (77% vs. 32%, p = .001); similar results were noted for those who rated their buddy as supportive (65% vs. 31%, p = .002). Average change from baseline to 3-month follow-up in nonprogram–related social support from friends, family, and a special person was similar between those who found their Text Buddy helpful and supportive and those who did not however (e.g., Text Buddy was unsupportive: M = 3.0, SD = 12.0; supportive: M = 1.7, SD = 11.6; p = .62).

Table 5.

Appraisal of Intervention Components Among Intervention Participants Who Responded at 3 Months

| Program component | All intervention participant respondents% (n) | Users of study component% (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Text Buddy | n = 80 | n = 42 |

| How helpful was your buddy | ||

| Very unhelpful | 19% (15) | 26% (11) |

| Somewhat unhelpful | 9% (7) | 5% (2) |

| Neither | 56% (45) | 48% (20) |

| Somewhat helpful | 10% (8) | 14% (6) |

| Very helpful | 6% (5) | 7% (3) |

| How supportive was your buddy | ||

| Very unsupportive | 15% (12) | 19% (8) |

| Somewhat unsupportive | 5% (4) | 2% (1) |

| Neither | 51% (41) | 40% (17) |

| Somewhat supportive | 19% (15) | 26% (11) |

| Very supportive | 10% (8) | 12% (5) |

| Shared personal information with buddy (yes) | 11% (9) | 21% (9) |

| …and contacted buddy after the program was over (yes) | 22% (2) | 22% (2) |

| Text Crave | n = 80 | n = 11 |

| How helpful was Text Crave | ||

| Very unhelpful | 9% (7) | 10% (3) |

| Somewhat unhelpful | 5% (4) | 3% (1) |

| Neither | 25% (20) | 16% (5) |

| Somewhat helpful | 40% (32) | 52% (16) |

| Very helpful | 21% (17) | 19% (6) |

One in three intervention participants (34%) used the Text Crave automated support at least once during the program. Usage ranged from 1 to 15 messages (M = 3.5, SD = 3.3). Users and nonusers were similar by participant sex, age, smoking intensity, and school status. There was some indication that users were less likely to be minority race (22%) compared with nonusers (40%, p = .07). Sixty-one percent rated Text Crave as somewhat or very helpful. Participants who found Text Crave helpful were more likely than those who did not quit at 3 months (55% vs. 28%, p = .001).

There were 355 hits on the Web site main page during the 3 months of field. The most popular subpage was the Board, which received 198 page views. Only 11 user accounts were created and seven posts posted, however. One particularly poignant example was this unanswered post: “was just wondering what people thought of the text messages so far? not sure if anyone is out there…my quit day is coming up july 1. What about you guys?”

DISCUSSION

Findings from the pilot RCT of SMS USA suggest that the intervention affects self-reported quitting rates at 4 weeks, as verified by a significant other, in a sample that includes those traditionally not incorporated into smoking cessation research in the United States. Quitting rates are not significantly different for SMS USA participants and control participants at 3 months postquit. The study is not powered to detect significant differences (as is consistent with pilot designs)—particularly within subgroups. Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed before conclusions can be drawn. Current data suggest intriguing areas for future inquiry however, including that the program might be particularly helpful for young adults outside of higher education settings, a group of young smokers traditionally not included in smoking cessation research. Other groups who may also benefit from the program to a greater degree might be non-White and male participants.

Findings also suggest that SMS USA is acceptable among this understudied population. The extensive development activities (Ybarra, Prescott, & Holtrop, 2012) seem to have resulted in salient content that is neither disruptive nor too frequent. Unlike previous studies that have offered the Text Buddy as an opt-in intervention component (Free et al., 2011; Rodgers et al., 2005; Whittaker et al., 2009), all participants are assigned a buddy in SMS USA. Although only half of participants sent a message to their buddy and the component did not receive positive ratings from the majority of participants, those who found their buddy to be supportive and helpful were significantly more likely to quit. Text Crave was utilized by only one in three participants but it received positive ratings by two in three users and was associated with increased likelihood of quitting. It may be that text messaging–based smoking cessation programs are more effective for smokers who are open to using these types of components, and those who do not may find other types of cessation programs (e.g., telephone quit lines) to be better aligned with their quitting needs.

SMS USA appears to be effective in reaching people who might otherwise not access evidence-based smoking cessation programs: more than two in three (71%) had never used an evidence-based quitting aid (i.e., pharmacotherapy, individual therapy, or group therapy) before enrolling in SMS USA. This may in part be because of the study’s unique outreach to young adults outside of higher education settings. Indeed, 57% of participants are working and 59% are not currently enrolled in higher education courses. The sample also is racially and economically diverse: 35% are non-White and 43% report an annual household income of less than $15,000. It also is majority male (56%). Although the ability for technology-based interventions to reach a wide range of people is often touted, it is rarely realized in research studies. Instead, smoking cessation study samples recruited online tend to be more female, White, and educated compared with the general smoking population (Cobb, Graham, Bock, Papandonatos, & Abrams, 2005; Feil, Noell, Lichtenstein, Boles, & McKay, 2003; Stoddard et al., 2005). Although we did not have specific recruitment goals, we purposefully targeted a diversity of communities and monitored the demographic characteristics of the sample to ensure a diverse sample. Given that lower income and racial minority groups are disproportionately represented in the smoking population (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1998, 2010), it is encouraging that results suggest that SMS USA has the potential to be especially beneficial to these groups.

This is one of the few studies to test a text messaging–based program against a blinded control group. Content was intentionally designed not to include components necessary to affect cessation (e.g., preparation for quitting) and instead talked about the importance of quitting within the context of improving one’s fitness and sleep. Three in four control participants said that the messages talked about what they were feeling and experiencing, suggesting that participants were successfully blinded with content that had perceived utility, yet provided insufficient transfer of skills for cessation. The observed difference in cessation rates between the two study groups is the first evidence to support the hypothesis that above and beyond the simple act of text messaging, content does matter when trying to affect cessation. Text messaging is simply the delivery mode; it is not the intervention itself. As with other delivery mechanisms (e.g., in-person, online), the messaging content is key to affecting behavior change. That said, it is curious that the cessation rate among intervention participants was stable between 4 weeks and 12 weeks, but increased among control participants. Unfortunately, we do not have data about the quitting experience for these newly quit control participants. Perhaps they were able to try quitting again as a result of improving their fitness and sleep first. Perhaps it is a function of small sample size (i.e., a few people moving into the “quit” category has a larger impact on the overall percentage of people who are quit).

Limitations

The main limitation of the study is its small sample size. As a feasibility study, it was not powered to detect differences in effects between the two arms. This is especially true for the six subgroup analyses conducted. Also, it is unclear how young adult smokers recruited on Craigslist compared with young adult smokers who would be recruited through other ways, particularly those who would enroll in a text-messaging program if it were publicly available. Additionally, there were problems with the randomization program, which resulted in manual assignment of the final eight participants to balance allocations. The resulting bias is judged to be minimal however, because of the small number of participants affected and the lack of differences in baseline characteristics between the two arms. Finally, 47 participants who were randomized could not be included in the ITT analyses because their allocation was not retained by the software program. Again, it seems unlikely that this limitation would have affected the findings. The purpose of ITT is to avoid misleading findings based upon differential dropout across the study arms (Lachin, 2000). In the current case, the 47 participants were not told their arm assignment; their dropout was unrelated to their randomization allocation and could not have lead to differential dropout between the two groups.

CONCLUSIONS

Findings provide reason for optimism that text messaging–based smoking cessation programs can affect quit rates among young adults, including groups that are typically underserved, at least in the short term. Future research should focus on establishing program efficacy with a fully powered sample, understanding mechanisms that affect and sustain cessation rates over time, and identifying profiles of users for whom the program may be particularly beneficial.

FUNDING

The project described was supported by Award Number R21CA135669 from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the entire Study team from Center for Innovative Public Health (Internet Solutions for Kids), Michigan State University, and the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth), who contributed to the planning and implementation of the study. We would also like to thank Dr. Zhongxue Chen for his preliminary work on the statistical analyses and to Dr. Amanda Graham for her consultation. We thank the study participants for their time and willingness to participate in this study. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

APPENDIX

Table A1.

Reasons for Study Ineligibility (n = 1,331)

| Reasons for study ineligibility | % (n) |

|---|---|

| Number of study eligibility criteria not met | |

| Did not meet one eligibility criteria | 74.6 (993) |

| Did not meet two eligibility criteria | 16.8 (224) |

| Did not meet three eligibility criteria | 7.4 (99) |

| Did not meet four or more eligibility criteria | 1.1 (15) |

| Reasons for ineligibility | (n = 1,798)a |

| Not planning on quitting in the next 30 days | 44.9 (808) |

| Age (not between 18 and 25 years old) | 18.1 (326) |

| Does not smoke six or more days per week | 10.0 (179) |

| Does not smoke four or more cigarettes per day | 9.7 (175) |

| Cell phone provider ineligible | 7.9 (142) |

| Does not own cell phone | 5.0 (90) |

| Do not have unlimited text messaging | 3.1 (56) |

| Other | 0.6 (11) |

| Unable to receive validation code | 0.4 (8) |

| Knows someone else participating in the study | 0.2 (3) |

Note. Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

aReasons for ineligibility were not mutually exclusive; therefore, a participant could be ineligible for more than one reason.

REFERENCES

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2009). Clinical guidelines for prescribing pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Retrieved from www.ahrq.gov/clinic/tobacco/ prescrib.htm [Google Scholar]

- Bader P., Travis H. E., Skinner H. A. (2007). Knowledge synthesis of smoking cessation among employed and unemployed young adults. American Journal of Public Health, 97, 1434–1443.10.2105/AJPH.2006.100909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. (1997). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215.10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1993). Smoking cessation during the previous year among adults -- United States, 1990 and 1991. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 42, 504–507 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1998). Tobacco use among U.S. racial/ethnic minority groups--African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, Hispanics: A report of the Surgeon General. MMWR Recommendations and Reports, 47, 1–16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2001). Women and smoking: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office on Health and Smoking; Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/2001/complete_report/index.htm [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2002). Cigarette smoking among adults -- United States, 2000. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 51, 642–645 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2010). Vital signs: Current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥18 years --- United States, 2009. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 59, 1135–1140 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011). Quitting smoking among adults--United States, 2001–2010. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 60, 1513–1519 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb N. K., Graham A. L., Bock B. C., Papandonatos G., Abrams D. B. (2005). Initial evaluation of a real-world Internet smoking cessation system. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 7, 207–216.10.1080/14622200500055319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhalla S., Kopec J. A. (2007). The CAGE questionnaire for alcohol misuse: A review of reliability and validity studies. Clinical and Investigative Medicine. Médecine clinique et experimentale, 30, 33–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton W. W., Muntaner C., Smith C., Tien A., Ybarra M. (2004). Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: Review and revision (CESD and CESD-R). In Maruish M. E. (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment (3rd ed., pp. 363–377). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; [Google Scholar]

- Emont S. L., Collins R. L., Zywiak W. H. (1991). Methodological note: Corroboration of self-reported smoking status using significant other reports. Addictive Behaviors, 16, 329–333.10.1016/0306-4603(91)90025-D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feil E. G., Noell J., Lichtenstein E., Boles S. M., McKay H. G. (2003). Evaluation of an Internet-based smoking cessation program: Lessons learned from a pilot study. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 5, 189–194.10.1080/ 1462220031000073694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Free C., Knight R., Robertson S., Whittaker R., Edwards P., Zhou W, … Roberts I. (2011). Smoking cessation support delivered via mobile phone text messaging (txt2stop): A single-blind, randomised trial. Lancet, 378, 49–55.10.1016/ S0140-6736(11)60701-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M. P., McCausland K. L., Xiao H., Duke J. C., Vallone D. M., Healton C. G. (2007). A closer look at smoking among young adults: Where tobacco control should focus its attention. American Journal of Public Health, 97, 1427–1433.10.2105/AJPH.2006.103945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R. L., Williams J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16, 606–613.10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachin J. M. (2000). Statistical considerations in the intent-to-treat principle. Controlled Clinical Trials, 21, 167–189.10.1016/S0197-2456(00)00046-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamkin L., Davis B., Kamen A. (1998). Rationale for tobacco cessation interventions for youth. Preventive Medicine, 27, A3–A8.10.1006/pmed.1998.0386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz P. M. (2003). Smoking on the rise among young adults: Implications for research and policy. Tobacco Control, 12(Suppl. 1)i60–i70.10.1136/tc.12.suppl_1.i60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrance L., Rubinson L. (1986). Self-efficacy as a predictor of smoking behavior in young adolescents. Addictive Behaviors, 11, 367–382.10.1016/0306-4603(86)90015–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May S., West R. (2000). Do social support interventions (“buddy systems”) aid smoking cessation? A review. Tobacco Control, 9, 415–422.10.1136/tc.9.4.415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W. R., Zweben A., DiClemente C. C., Rychtarik R. G. (1992). Motivational Enhancement Therapy Manual: A clinical research guide for therapists treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Retrieved from http://casaa.unm.edu/manuals/met.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Murphy-Hoefer R., Griffith R., Pederson L. L., Crossett L., Iyer S. R., Hiller M. D. (2005). A review of interventions to reduce tobacco use in colleges and universities. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28, 188–200.10.1016/j.amepre.2004.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrom B. L., Kinnunen T., Utman C. H., Krall E. A., Vokonas P. S., Garvey A. J. (2000). Predictors of continued smoking over 25 years of follow-up in the normative aging study. American Journal of Public Health, 90, 404–406.10.2105/AJPH.90.3.404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obermayer J. L., Riley W. T., Asif O., Jean-Mary J. (2004). College smoking-cessation using cell phone text messaging. Journal of American College Health, 53, 71–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossip-Klein D. J., Giovino G. A., Megahed N., Black P. M., Emont S. L., Stiggins J, … Moore L. (1991). Effects of smokers’ hotline: Results of a 10-county self-help trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59, 325–332.10.1037/0022-006X.59.2.325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeder A. I., Williams S., McGee R., Poulton R. (2001). Nicotine dependence and attempts to quit or cut down among young adult smokers. The New Zealand Medical Journal, 114, 403–406 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers A., Corbett T., Bramley D., Riddell T., Wills M., Lin R. B., Jones M. (2005). Do u smoke after txt? Results of a randomised trial of smoking cessation using mobile phone text messaging. Tobacco Control, 14, 255–261.10.1136/tc.2005.011577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher K. J., Gotham H. J., Erickson D. J., Wood P. K. (1996). A prospective, high-risk study of the relationship between tobacco dependence and alcohol use disorders. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 20, 485–492.10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb01079.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumaker S. A., Grunberg N. E. (1986). Proceedings of the National Working Conference on Smoking Relapse: July 24–26, 1985, Bethesda, Maryland. Health Psychology, 5(Suppl), 1–99 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. (2011). Americans and text messaging. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; Retrieved from http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2011/Cell-Phone-Texting-2011/Main-Report/How-Americans-Use-Text-Messaging.aspx [Google Scholar]

- Solberg L. I., Asche S. E., Boyle R., McCarty M. C., Thoele M. J. (2007). Smoking and cessation behaviors among young adults of various educational backgrounds. American Journal of Public Health, 97, 1421–1426.10.2105/AJPH.2006.098491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp (2009). Stata Statistical Software: Release 11. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard J., Delucchi K., Munoz R., Collins N., Stable E. P., Augustson E., Lenert L. (2005). Smoking cessation research via the internet: A feasibility study. Journal of Health Communication, 10, 27–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone S. L., Kristeller J. L. (1992). Attitudes of adolescents toward smoking cessation. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 8, 221–225 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2004). Results from the 2003 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings (NSDUH Series H–25, DHHS Publication No. SMA 04–3964). Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; Retrieved from www.oas.samhsa.gov/nhsda/2k3nsduh/2k3Results.htm [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2011). Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings (NSDUH Series H-41, DHHS Publication No. SMA 11–4658). Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Retrieved from www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2k10NSDUH/2k10Results.htm [Google Scholar]

- Taves D. R. (1974). Minimization: A new method of assigning patients to treatment and control groups. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 15, 443–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2012). Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Retrieved from www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/preventing-youth-tobacco-use/full-report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- West R., Hajek P., Stead L., Stapleton J. (2005). Outcome criteria in smoking cessation trials: Proposal for a common standard. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 100, 299–303.10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00995.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker R., Borland R., Bullen C., Lin R. B., McRobbie H., Rodgers A. (2009). Mobile phone-based interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, CD006611.10.1002/14651858.CD006611.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams G. C., McGregor H., Borrelli B., Jordan P. J., Strecher V. J. (2005). Measuring tobacco dependence treatment outcomes: A perspective from the behavior change consortium. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 29(Suppl), 11–19.10.1207/s15324796abm2902s_4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ybarra M. L., Prescott T. L., Holtrop J. S. (2012). Steps in tailoring a text messaging-based smoking cessation program for young adults. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhu S. H., Stretch V., Balabanis M., Rosbrook B., Sadler G., Pierce J. P. (1996). Telephone counseling for smoking cessation: Effects of single-session and multiple-session interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 202–211.10.1037/0022-006X.64.1.202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet G. D., Dahlem N. W., Zimet S. G., Farley G. K. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52, 30–41.10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]