Abstract

Background:

The time between the onset of symptoms and reperfusion is a critical determinant of the clinical course of patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Any delay in seeking help will affect patient’s outcome. Alexithymia can influence the information processing but also the skills to detect the signal of an ongoing AMI.

Method:

Systematic review and meta-analysis of studies investigating the role of alexithymia in pre-hospital delay after AMI. Pubmed/Medline and PsychINFO/Ovid search from 1990 until 2012.

Results:

Out of 29 studies investigating the role of psychological factors in pre-hospital delay after AMI, 3 studies specifically assessed alexithymia, involving 258 patients. All studies used the Toronto Alexithymia Scale to group patients into clusters by time to presentation after AMI. Meta-analysis of data showed that the patients with higher emotional awareness (i.e., low alexithymia) had shorter time to presentation after AMI.

Conclusions:

Preliminary evidence indicates that alexithymia may have a role in seeking help delay after AMI. Further studies are necessary to better appreciate how alexithymia influence help-seeking in patients with an evolving AMI and in what extent their ineffective behavior can be changed.

Keywords: Pre-hospital delay, acute myocardial infarction, alexithymia, psychological factors, care seeking behavior.

1. INTRODUCTION

The time between the onset of symptoms and reperfusion is a critical determinant of the clinical course of patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). The degree of myocardial necrosis is related to the length of the ischemic episode [1, 2]. Survival after AMI depends of the early application of medical interventions as thrombolytic and other reperfusion techniques. Any delay in seeking help will affect patient’s ultimate outcome.

The decision of seeking help is based on both somatic (signs of the incoming infarction) and psychological (the emotional reaction to the event, the capacity of dealing with stress) factors. In the study of the determinant of pre-hospital delay in seeking help, clinical variables were given priority, such as previous infarction, atypical symptoms presentation, or co-morbidity with other medical diseases (i.e., diabetes), symptoms onset context (i.e.: being/living alone) and first consulting with a family member or a physician. Factors such as older age, female sex, and lower socio-economic status were also related to pre-hospital delay after AMI. However, all these factors were found to contribute to decisional time but did not explain delay independently.

Psychological factors are likely to be implied in the patient’s decisional delay. Patients were reported to have poor appraisal of symptoms, or to express wrong causal beliefs about them; ineffective coping strategies, external health locus of control, low neuroticism and depressed mood were also related to increased time to seeking help after AMI [3-8]. Alexithymia might be an overarching element behind many of the psychological factors implied in pre-hospital delay after AMI [9].

Alexithymia was defined as a deficiency in understanding, processing, or describing emotions [10]. The alexithymia construct is composed by four major factors; 1) difficulty in identifying feelings and distinguishing between feelings and the bodily sensations of emotional arousal; 2) difficulty in describing feelings to other people; 3) poor imaginative processes, as evidenced by a paucity of fantasies; and 4) a stimulus-bound, externally oriented cognitive style [11-13]. Alexithymia can influence the information processing but also the skills to detect the signal of illness. People with alexithymia are more likely to experience wrong appraisal and interpretation of symptoms, and because their difficulty in describing feelings to other people, they can be poor in reporting symptoms at the first consultation with a physician.

In so far, a few studies only had investigated the role of alexithymia in pre-hospital delay after AMI, and obtained ambiguous results [14-16]. There is agreement that meta-analysis is the best method to summarize data, even when the studies are a few [17]. This study reports the first systematic review and meta-analysis of the studies that assessed the role of alexithymia in pre-hospital delay after AMI.

2. METHODS

The electronic databases Pubmed/Medline and PsychINFO/Ovid were searched for articles meeting the following inclusion criteria: (1) original papers written in English, (2) published from the period 1990 until 2012 and (3) containing the key words: “prehospital delay” OR “patient delay” OR “care seeking behavior” OR “alexithymia” AND “myocardial infarction”. Latest search performed on August 31, 2012.

Review papers and studies that did not clearly define pre-hospital or decisional delay, and those that did not considered psychological factors as determinant of delay were excluded.

The meta-analysis was carried out with the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (version 2.2) software (http://www.meta-analysis.com/). Effect sizes were calculated as Hedges’ adjusted g with 95% Confidence of interval (CI).

3. RESULTS

The initial search identified 1687 articles from PubMed and PsychInfo. After exclusion of duplicate, reviews and articles unrelated to the topics on the basis of the abstract, a total of 48 articles were considered in detail, 29 of them investigated psychological factors. We found two studies that specifically assessed alexithymia as a factor involved in pre-hospital delay after AMI; a third study was done by our group and it is still in press (Table 1). The three studies investigated levels of alexithymia with different version of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS) [12, 13], albeit congruent in the use of cut-off to define alexithymia caseness. Further details on alexithymia scores in Table 2 and 3.

Table 1.

Included Studies

| Study | Study Design | Sample Size | Pre-Hospital (PH) or Decisional Delay (D) Time | Cut-off of Pre-Hospital Delay in Case-Control Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kenion et al., 1991 | Cohort | 103 | PH: mean=9 sd=10,8 (hours) | |

| O'Carrol et al., 2001 | Case-control | 72 | PH: mean=474,7 median=167 (minutes) | > 4 hours (delayers) |

| Carta et al., 2013 | Case-control | 83 | PH: mean=176,75 sd=239.65 | > 2 hours (delayers) |

Table 2.

Results of Kenion et al, 1991 and Carta et al, 2012

| TAS | % Kenion et al. | Time (hours) | % Carta et al. | Time (hours) | Kenion + Carta | ANOVA 1 way |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low and Intermediate emotional awareness | 42 (41%) | 10.3±10.0 | 30 (36%) | 4.9±5.8 | 8.05±8.2 | F=14.3 DF=1,184,185 |

| High emotional awareness | 61 (59%) | 7.6±9 | 53 (645) | 2.1±3.0 | 5.04±6.2 | P<0.0001 |

Table 3.

Results of O’Carrol et al., 2001 and Carta et al., 2012

| % O’Carrol | TAS Mean O’Carrol | % Carta | TAS mean Carta | O’Carrol + Carta | ANOVA 1 way | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prompt | 48 (64.7%) | 53.9±11.7 | 75 (89.2) | 51.0±9.73 | 52.1±10.5 | F=7.31 DF=1,154,155 |

| Delayed (>4hs) | 24 (33.3%) | 56.7±8.9 | 9 (10.8) | 59.9±12.88 | 57.6±9.9 | P<0.008 |

3.1. Summary of Results

Kenion et al. [14] found no association of patients’ delay with demographic or medical history variables. Instead, they found that patients more capable of identifying inner experiences of emotions and/or bodily sensations sought treatment significantly earlier than patients with low emotional or somatic awareness, i.e. those with higher scores on the measure of alexithymia.

O’Carrol et al. [15] found that patients who delayed presentation for medical help after AMI had lower scores on a measure of neuroticism and higher scores on a measure of denial. They also grouped patients by time of presentation after AMI into three clusters of “high alexithymics”, “intermediate alexithymics” and “low alexithymics”: prompt presenters (< 4 hours) were less likely to be “high alexithymics” than the delayed presenters (>4 hours), but these differences did not reach the threshold for statistical significance.

In a case-control study, Carta et al. [16] included 83 AMI patients (61 [73,5%] males). In this study the time to presentation was calculated as the estimated interval from symptoms’ onset to first EEG. In the sample, 36 patients (43.4%) had more than 120 minutes of time to presentation and were enrolled in the Group of late responders (mean ± sd “time to presentation” = 320,72 ± 309,44); 47 patients (56.6%) had less than 120 minutes of time to presentation and were enrolled in the Group of early responders (66,47 ± 29,66). Higher alexithymia scores (TAS-20 ≥ 61) (OR 3.7, Cl 95% 1.3-10.1, p<0.01) and having contact with primary care (OR 3.5, Cl 95% 1.3-9.3, p<0.01) were associated with increased time to treatment in AMI. Socio-demographic or clinical variables were not related with time to presentation.

3.2. Results of the Meta-Analysis

In the study of Kenyon et al. [15] the overall mean of time of presentation was compared in two groups of “alexithymics” and “not alexithymics”, therefore we subdivided data bank of the study of Carta et al. (2012) in the same way. The study of O’Carrol et al. [14] compared the alexithymia in a group of patient with AMI prompt presenters (< 4 hours) and a group of AMI delayed presenters (>4 hours). For this comparison we re-analyzed data of the study of Carta et al. [16] subdividing in same way the sample.

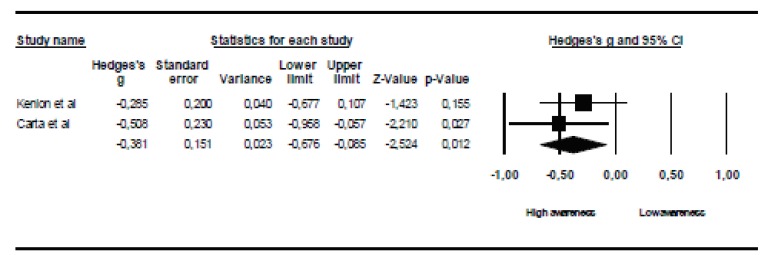

Table 1 and Fig. (1) present the results of the meta-analysis summarizing the data of the study of Carta et al. [16] with that of Kenion et al. [15]. The pooled data showed statistically significant differences between “low and Intermediate emotional awareness (TAS ≥61)” and “high emotional awareness” (TAS <61)” subgroups, with patients with “high emotional awareness” showing a shorter time to presentation.

Fig. (1).

Meta-analysis of the studies of Kenion et al., 1991 and Carta et al., 2012.

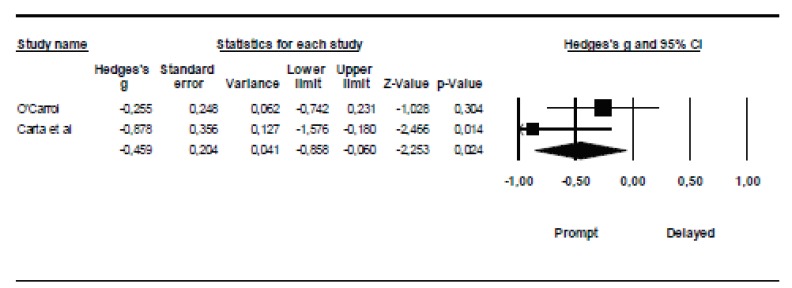

Table 2 and Fig. (2) presents the results of the meta analysis summarizing the data of the study of Carta et al. [16] with the O’ Carrol et al. [14] study. In the sample of Carta’s study a very few people had a delayed time outmatching 4 hours (9,10.8%). The pooled data showed statistically significant differences between the mean scores at TAS between “prompt” (elapsed time <4 hours) and “delayed” (>4hours) groups, with patients in the prompt group showing lowers scores on the TAS.

Fig. (2).

Meta-analysis of the studies of O’Carrol et al., 2001 and Carta et al., 2012.

4. DISCUSSION

Three studies in so far explored the role of alexithymia in pre-hospital delay after AMI. Higher levels of alexithymia associated with higher delay time in seeking medical help after AMI [14-16]. The finding was clearer in the Kenion et al. [15] and in the Carta et al. [16] study than in the O’Carroll et al. [14] study. Nevertheless, in the study of O’Carroll and colleagues, alexithymia levels were, non-significantly, higher in “delayers” than in “prompt attenders” (TAS-20 mean scores: 56.7 ± 8.9 vs 53.9 ± 11.1), albeit with a too long threshold to identify “prompter attender”: “< 4 hours”.

Alexithymia may affect the experience and reporting of physical symptoms, thus having an impact on the seeking of treatment [18]. It can be hypothesized that AMI is unrecognized by alexithymic patients, because they fail to notice or report the event to the physician, or make the physician unable to diagnose it because they report confusedly their symptoms. In a past study, Theisen and collegues [19] found that those patients who failed to recognize an ongoing AMI (n = 30) had higher alexithymia scores on the Alexithymia Provoked Response Interview than those patients (n = 40) who correctly sought treatment when symptoms of AMI started. Patients unable to correctly identify their ongoing AMI also were more likely to hold the belief that chance factors determine their health (as assessed with the Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scale). Poor awareness of psychological factors was suggested a factor preventing AMI symptom perception or recognition, alexithymia possibly contributing to the belief that chance or fate do determine health, so inhibiting treatment seeking [19].

5. CONCLUSION

Findings must be considered preliminary, nevertheless the evidence suggest that alexithymia may have a role in pre-hospital delay after AMI. It can be hypothesized that patients more capable of identifying inner experiences of emotions and bodily sensations would be more likely to seek right treatment earlier for symptoms of AMI. In the past alexithymia was conceived an unchangeable trait dimension, but it was demonstrated that it may display sensitivity to change in specific situations [20-23]. Preliminary findings suggest that intranasal oxytocin may improve social-emotional abilities of individuals with alexithymia [24]. Due to paucity of current evidence, further studies are necessary to better appreciate how alexithymia influence help-seeking in patients with an evolving AMI and in what extent their ineffective behavior can be changed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

MGC had the idea and organized the study; he also wrote the first draft of the article. FS did the systematic review and contributed to the study design and to the first draft of the article. AP contributed to the systematic review, to the study design and to the first draft of the article; he also did the meta-analysis. FC contributed to the study design and to the first draft of the article. All authors contributed to the writing of the final manuscript, which they all approved for submission. Each author has studied the manuscript in the submitted form, has agreed to be cited as co-author, and has accepted the order of authorship;

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boersma E, Maas AC, Deckers JW, Simoons ML. Early thrombolytic treatment in acute myocardial infarction: reappraisal of the golden hour. Lancet. 1996;21:771–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)02514-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Von HA, Hogan N, Ochs AL, Shapiro M. Time to treatment for acute coronary syndromes: the cost of indecision. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010;25(2):106–14. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181bb14a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kenyon LW, Ketterer MW, Preisman RC. Psychological factors relevant to the prehospital and in-hospital phases of acute myocardial infarction. Henry Ford Hosp Med J. 1991;39(3-4):176–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khraim FM, Scherer YK, Dorn JM, Carey MG. Predictors of decision delay to seeking health care among Jordanians with acute myocardial infarction. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2009;41(3):260–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2009.01287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moser DK, Kimble LP, Alberts MJ, et al. Reducing delay in seeking treatment by patients with acute coronary syndrome and stroke: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on cardiovascular nursing and stroke council. Circulation. 2006;(2):168–82. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubayova T, van Dijk JP, Nagyova I, et al. The impact of the intensity of fear on patient's delay regarding health care seeking behavior: a systematic review. Int J Public Health. 2010;55(5):459–68. doi: 10.1007/s00038-010-0149-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dracup K, Moser DK, Eisenberg M, Meischke H, Alonzo AA, Braslow A. Causes of delay in seeking treatment for heart attack symptoms. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(3):379–92. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gärtner C, Walz L, Bauernschmitt E, Ladwig KH. The causes of prehospital delay in myocardial infarction. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2008;105(15):286–91. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2008.0286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sancassiani F, Preti A, Cadoni F, Carta MG. The role of psychological factors and alexithymia in seeking care during acute myocardial infarction: a systematic review. PloS ONE. 2013 [submitted] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sifneos PE. The prevalence of 'alexithymic' characteristics in psychosomatic patients. Psychother Psychosom. 1973;22(2):255–62. doi: 10.1159/000286529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richards HL, Fortune DG, Griffiths CE, Main CJ. Alexithymia in patients with psoriasis: clinical correlates and psychometric properties of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale-20. J Psychosom Res. 2005;58(1):89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, Parker JD. The 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale, IV. Reliability and factorial validity in different languages and cultures. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55:277–83. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor GJ, Bagby RM, Ryan DP, Parker JDA, Doody KF, Keefe P. Criterion validity of the Toronto Alexithymia Scale. Psychosom Med. 1988;50:500–9. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198809000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Carroll RE, Smith KB, Grubb NR, Fox KAA, Masterton G. Psychological factors associated with delay in attending hospital following a myocardial infarction. J Psychosomat Res. 2001;51:611–4. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kenyon LW, Ketterer MW, Gheorghiade M, Goldstein S. Psychological factors related to prehospital delay during acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1991;84(5):1969–76. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.5.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carta MG, Sancassiani F, Pippia V, Bhat KM, Sardu C, Meloni L. Alexithymia is associated with delayed treatment seeking in acute myocardial infarction. Psychother Psychosom. 2013 doi: 10.1159/000341181. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valentine JC, Pigott TD, Rothstein HR. How many studies do you need? a primer on statistical power for meta-analysis. J Educ Behav Stat. 2010;35:215–47. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lumley MA, Neely LC, Burger AJ. The assessment of alexithymia in medical settings: implications for understanding and treating health problems. J Pers Assess. 2007;89(3):230–46. doi: 10.1080/00223890701629698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Theisen ME, MacNeill SE, Lumley MA, Ketterer MW, Goldberg AD, Borzak S. Psychosocial factors related to unrecognized acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1995;75(17):1211–3. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80764-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luminet O, Bagby RM, Taylor GJ. An evaluation of the absolute and relative stability of alexithymia in patients with major depression. Psychother Psychosom. 2001;70:254–60. doi: 10.1159/000056263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beresnevaite M. Exploring the benefits of group psychotherapy in reducing alexithymia in coronary heart disease patients: a preliminary study. Psychother Psychosom. 2000;69(3):117–22. doi: 10.1159/000012378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tulipani C, Morelli F, Spedicato MR, Maiello E, Todarello O, Porcelli P. Alexithymia and cancer pain: the effect of psychological intervention. Psychother Psychosom. 2010;79(3):156–63. doi: 10.1159/000286960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carta MG, Balestrieri M, Murru A, Hardoy MC. Adjustment Disorder: epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2009;5:15. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-5-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luminet O, Grynberg D, Ruzette N, Mikolajczak M. Personality-dependent effects of oxytocin: greater social benefits for high alexithymia scorers. Biol Psychol. 2011;87(3):401–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]