Abstract

The studies described herein assess the potential of combining platinum-based chemotherapy with high-linear energy transfer (LET) α-particle-targeted radiation therapy using trastuzumab as the delivery vehicle. An initial study explored the combination of cisplatin with 213Bi-trastuzumab in the LS-174T i.p. xenograft model. This initial study determined the administration sequence of cisplatin and 213Bi-trastuzumab. Cisplatin coinjected with 213Bi-trastuzumab increased the median survival (MS) to 90 days versus 65 days for 213Bi-trastuzumab alone. Toxicity was observed with a weight loss of 17.6% in some of the combined treatment groups. Carboplatin proved to be better tolerated. Maximal therapeutic benefit, that is, a 5.1-fold increase in MS, was obtained in the group injected with 213Bi-trastuzumab, followed by carboplatin 24 hours later. This was further improved by administration of multiple weekly doses of carboplatin. The MS achieved with administration of 3 doses of carboplatin was 180 days versus 60 days with 213Bi-trastuzumab alone. The combination of carboplatin with 212Pb radioimmunotherapy was also evaluated. The therapeutic efficacy of 212Pb-trastuzumab (58-day MS) increased when the mice were pretreated with carboplatin 24 hours prior (157-day MS). These results again demonstrate the necessity of empirically determining the administration sequence when combining therapeutic modalities.

Key words: α-particle, 213Bi, carboplatin, cisplatin, HER2, 212Pb, radioimmunotherapy, trastuzumab

Introduction

The benefit of treating disseminated peritoneal disease with targeted α-particle radiation continues to be demonstrated in preclinical studies.1–8 At this juncture, studies from this laboratory have focused on targeting HER2-expressing tumors with 212Pb and 213Bi using trastuzumab as the delivery vehicle.1–4 A direct result of this work has been initiation of a clinical study at the University of Alabama assessing the safety of 212Pb-1,4,7,10-tetraaza-1,4,7,10-tetra-(2-carbamoyl methyl)-cyclododecane (TCMC)-trastuzumab radioimmunotherapy (RIT) administered by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection. Patients under recruitment are those with HER2-positive peritoneal neoplasms of ovarian, pancreatic, and gastric origin (NCT01384253). The success of treating and managing patients with RIT, however, as with any treatment regimen for cancer, will no doubt require a multimodality approach, and the development of such treatment regimens remains a priority for investigators. One strategy has been to identify cytotoxic and/or radiosensitizing agents that would enhance the therapeutic response to RIT. Thus far, studies from this laboratory have included the assessment of the potentiation of α-targeted therapy by the chemotherapeutics gemcitabine and paclitaxel.2,4

Gemcitabine (Gemzar), a nucleotide analog, inhibits DNA synthesis through a number of mechanisms, serves as a radiosensitizer, and is a standard of care for pancreatic cancer patients.9–11 Studies from this laboratory demonstrated that gemcitabine improved the median survival (MS) of tumor-bearing mice 1.6-fold when it was administered i.p. the day before 212Pb-trastuzumab.2 The MS was further improved with additional weekly doses of gemcitabine. Gemcitabine was found to provide the greatest benefit when a multicycle treatment regimen was implemented; 2 doses of 212Pb-trastuzumab and a total of 4 doses of gemcitabine extended the MS to 196.5 days as compared to 45 days after a single injection of 212Pb-trastuzumab.2

Studies were then extended to paclitaxel. The choice of paclitaxel was based on the fact that (1) it is used in the treatment of ovarian and pancreatic cancer; (2) it is recognized as a radiosensitizer, and (3) its mechanism of action differed distinctly from that of gemcitabine. Paclitaxel given 24 hours after 213Bi-trastuzumab increased the MS of mice bearing i.p. tumors 6.7–9-fold versus 2.1-fold for 213Bi-trastuzumab alone. Weekly doses of paclitaxel provided further benefit. Paclitaxel was also found to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of 212Pb-trastuzumab when given before the RIT.

The mechanism of action by the platinum-based drugs differs from both gemcitabine and paclitaxel and as such would add another class of chemotherapeutics to the armamentarium to be combined with radiolabeled antibodies. Enhanced cell killing has been reported when platinum analogs have been administered in combination with radiation.12,13 A primary mechanism of action attributed to cisplatin is that once it is taken up by a cell, it is activated (via aquation) and forms platinum–DNA adducts. These adducts distort DNA, activating repair pathways whose failure leads to cell death. The platinum–DNA adducts can also interfere with the cellular machinery, resulting in cell cycle arrest as well as the pathways of cell growth, differentiation, and stress responses.

The studies described herein evaluate the potential of platinum chemotherapy to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of both HER2-targeting α-emitting high-linear energy transfer (LET) 213Bi- and 212Pb-labeled trastuzumab. The ultimate goal was to establish a multimodality regimen for the management of patients with disseminated intraperitoneal disease.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines

Unless otherwise stated, media and supplements were purchased from Lonza. Therapy studies were conducted using the LS-174T, a human colon carcinoma cell line, grown in Dulbecco's minimum essential medium supplemented with 1 mM glutamine as previously described.14 SKOV-3, a human ovarian carcinoma cell line that expresses ∼1×106 HER2 molecules per cell, was used for in vitro analysis of the radioimmunoconjugates.15 The SKOV-3 cells were maintained in McCoy's 5a medium. Both media were also supplemented with 10% FetalPlex (Gemini Bioproducts; 100–602) and 1 mM nonessential amino acids.

Chelate synthesis and monoclonal antibody conjugation

The bifunctional ligands, TCMC and cyclohexyl-A” diethylene-triamine-pentaacetic acid (CHX-A″-DTPA), and their conjugation with trastuzumab (Herceptin, Genentech, Inc.), purchased through the National Institutes of Health, Division of Veterinary Resources Pharmacy, have been previously described in detail.16,17 The final concentration of trastuzumab and HuIgG was determined by the method of Lowry using a bovine serum albumin (BSA) standard.18 The number of CHX-A″-DTPA or TCMC molecules linked to each of the preparations was determined using spectrophotometric assays based on the titration of either the yttrium– or lead–Arsenazo(III) complex, respectively.19,20 Polyclonal HuIgG (ICN), chosen to serve as a negative control in these studies, was similarly conjugated with CHX-A″-DTPA or TCMC and evaluated as described above. The HuIgG was purified from human serum, and as of yet, no known antigen has been described with which it reacts.

Radiolabeling

213Bi was obtained from a 225Ac/213Bi generator (Oak Ridge National Laboratories or Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.). 213Bi was eluted and trastuzumab- and HuIgG-CHX-A″ were radiolabeled as previously described.21 The elution of 212Pb from an 224Ra/212Pb generator (AlphaMed, Inc.) and the subsequent radiolabeling of trastuzumab- and HuIgG-TCMC have been detailed elsewhere.4

Radioimmunoassay

Immunoreactivities of the radiolabeled preparations were assessed in a radioimmunoassay using methanol-fixed cells.22 Briefly, serial dilutions of radiolabeled trastuzumab (∼140 to 8 nCi) were added in duplicate to methanol-fixed SKOV-3 cells (1×106) in 50 μL of 1% BSA in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cells were washed with 4 mL of 1% BSA in PBS after a 2-hour (213Bi) or 18-hour (212Pb) incubation at room temperature, pelleted at 1000 g for 5 minutes, and the supernatant decanted. 212Pb was detected using a Ge(Li) detector (EG&G Ortec; Model GEM10185-P), whereas 213Bi was measured in a γ-counter (PerkinElmer; WizardOne). The binding percentage is an average of the calculated percentage for each dilution. The specificity of the radiolabeled trastuzumab was confirmed by incubating one set of cells with ∼200,000 cpm of radiolabeled trastuzumab and an excess (5 μg) of unlabeled trastuzumab.

Therapy studies

Therapy studies were performed using 19–21-g female athymic (nu/nu) mice (Charles River Laboratories). The mice were injected i.p. with 1×108 cells LS-174T in 1 mL of medium as previously published.1,23 213Bi-CHX-A″-trastuzumab (500 μCi) or 212Pb-TCMC-trastuzumab (10 μCi) was administered i.p. to mice in 0.5 mL PBS. HuIgG labeled with 213Bi or 212Pb served as a nonspecific control. In all of the experiments, RIT was administered 3 days after tumor implantation.

In Study 1, mice (n=10–11) with i.p. LS-174T xenografts were injected (i.p.) with 125 μg (in PBS, 0.5 mL) of cisplatin 24 hours before, concurrently, or 24 hours after injection of 500 μCi 213Bi-labeled trastuzumab or HuIgG. Additional groups of mice received cisplatin, 213Bi-trastuzumab, 213Bi-HuIgG, or were left untreated. The experiment was designed to determine the sequence of cisplatin and 213Bi-RIT injections. This same experimental design was repeated for the evaluation of carboplatin (Study 2). In this case, the mice (n=9–10) were given i.p. injections of 1.25 mg of carboplatin in 0.5 mL of PBS.

Study 3 involved assessing the effectiveness of multiple dosing with a platinum chemotherapeutic combined with targeted α-particle radiation. Mice (n=9–15) bearing i.p. tumor xenografts were injected with carboplatin 24–30 hours after the injection of 213Bi-trastuzumab or 213Bi-HuIgG, followed by additional weekly injections of carboplatin for up to a total of 3 doses. Additional groups of mice included those injected with 3 doses of carboplatin at weekly intervals, with either 213Bi-trastuzumab or 213Bi-HuIgG alone, or no targeted radiation treatment.

Study 4 assessed the combination of carboplatin with 212Pb-RIT. Tumor-bearing mice (n=10) were injected with carboplatin (1.25 mg) 24 hours before, concurrently, or 24 hours post-treatment with 10 μCi of 212Pb-trastuzumab or 212Pb-HuIgG. These treatment groups were compared to the sets of mice those received carboplatin only, 212Pb-trastuzumab, 212Pb-HuIgG, or to those without any treatment.

Progression of disease was observed as an extension of the abdomen, development of ascites, or noticeable, palpable, nodules in the abdomen or, conversely, as weight loss. Mice were monitored and euthanized if found to be in distress, moribund, or cachectic. Mice were also euthanized when 10%–20% weight loss occurred, or disease progression was evident as cited above. All animal protocols were approved by the National Cancer Institute Animal Care and Use Committee.

Cell cycle analysis

Mice (n=3–5) utilized for the cell cycle and proliferation studies were injected i.p. with 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU; 1.5 mg in 0.5 mL PBS; Sigma) 4 hours before euthanasia. The tumors were collected and processed following the previously described procedures.24 Cell cycle distribution and DNA synthesis were determined by flow cytometry as described with some modifications.25 Tumors were fixed in cold 70% ethanol, washed in PBS, minced, and incubated in 1 mL 0.04% pepsin (Sigma) w/v in 0.1 N hydrochloric acid (HCl; Mallinckrodt, Inc.) for 1 hour at 37°C with shaking. The digest was filtered through a 70-μm nylon mesh after sequential passage through 23-, 25-, and 27-gauge needles. After centrifugation (10,000 g for 10 minutes), the resulting pellet was resuspended in 2 N HCl (1 mL) and incubated at 37°C for 20 minutes with shaking. The nuclear suspension was neutralized with 0.1 M sodium tetraborate (Sigma), washed in PBS containing 0.5% BSA and 0.5% Tween-20 (PBTB), and resuspended in PBTB. The nuclei (100 μL) were incubated with 20 μL of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled anti-BrdU monoclonal antibody (BD Biosciences-Pharmingen) for 1 hour at 4°C, followed by PBS washes. The samples were then resuspended in 2 mL of propidium iodide (50 μg/mL in PBTB; Sigma) containing RNAse A (50 μg; Sigma) and incubated for 30 minutes at 4°C. Flow cytometry was performed using a FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences), collecting 15,000 events. The DNA content (propidium iodide) and DNA synthesis (BrdU content) were analyzed using two-parameter data collection and analysis using CellQuest (BD Biosciences) software. A single-parameter analysis of the cell cycle distribution was performed using ModFit LT software (Verity Software House).

Statistical analyses

A Cox-proportional hazard model was used to test for a dose–response relationship between the treatment groups of 213Bi-trastuzumab or 212Pb-trastuzumab, and survival (time to sacrifice or natural death). Groups were compared using a log-rank test. A dose–response relationship was examined by treating the dose level as a linear covariate in the Cox model and tested whether the corresponding regression parameter was zero using a likelihood ratio test.

Differences between the treatment groups were tested using a Kruskal–Wallis test (nonparametric analysis of variance) for comparison of multiple groups, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was applied when comparing two groups. All reported p-values correspond to two-sided tests.

Results

The choice of 500 μCi and 10 μCi for 213Bi- and 212Pb-trastuzumab, respectively, was based on previous studies that determined that these doses were at the lower range of the maximum effective therapeutic dose.1,3 When combining α-particle RIT with chemotherapeutics, alterations in tumor sensitivity to radiation were considered and established to be more discernible if the lower-effective doses of 213Bi- or 212Pb-trastuzumab were administered, and any incipient toxicity incurred would not obscure observation of enhanced therapy.2,4

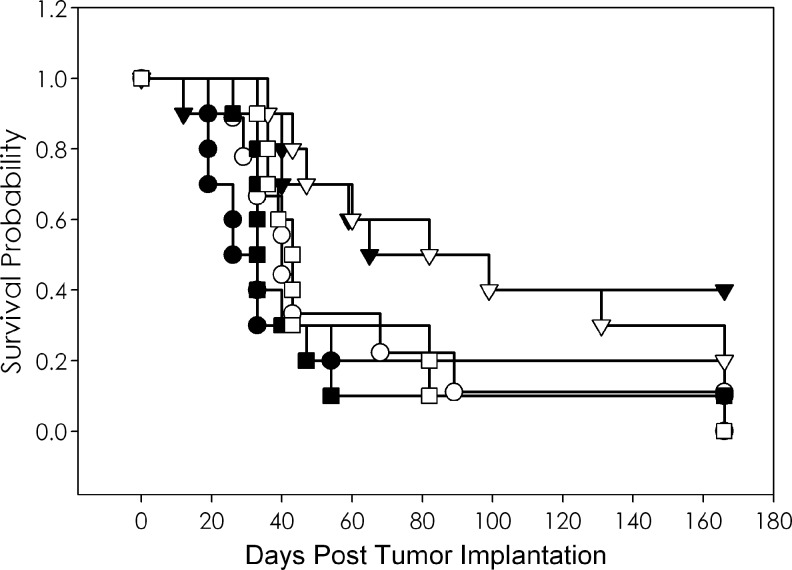

An initial study exploring the combination of platinum-based drugs with high-LET radiation was performed with cisplatin and 213Bi-trastuzumab in the LS-174T i.p. model. Based on a previous experience with paclitaxel, the study was designed to determine the administration sequence of cisplatin and 213Bi-trastuzumab.4 Tumor-bearing mice were treated i.p. with cisplatin (125 μg) 24 hours before, concurrently, or 24 hours after receiving 500 μCi of 213Bi-labeled trastuzumab or HuIgG. Control groups included mice given no treatment, cisplatin alone, 213Bi-trastuzumab, and 213Bi-HuIgG alone. The results detailed in Table 1 indicate that cisplatin alone exerted a modest affect on the LS-174T tumor xenografts. The untreated group of mice had a MS of 29.5 days, whereas animals given cisplatin only experienced an MS of 41.5 days. A MS of 65 days was obtained with the administration of 213Bi-trastuzumab and, as is usually observed, 213Bi-HuIgG provided some therapy with a MS of 33 days. The combination of cisplatin with 213Bi RIT had the appearance of improving the therapeutic efficacy. The group coinjected with 213Bi-trastuzumab and cisplatin had a MS of 90.5 days compared to 43 days for those mice treated concurrently with cisplatin and 213Bi-HuIgG (Fig. 1). The MS of those injected either before or after 213Bi-trastuzumab were 54 and 45 days, respectively. The MS for the corresponding groups injected with 213Bi-HuIgG was 59 and 39 days, respectively. The highest therapeutic index (the MS of the treatment group divided by the MS of the untreated group) of 3.1 was realized in the group that received coinjection of cisplatin and 213Bi-trastuzumab. These results appear promising; however, in this group, only 2 of 10 mice remained alive at the end of the study as compared to 4 of 10 for those that received just the 213Bi-trastuzumab. There was no significant difference in survival with respect to the timing of the cisplatin with either 213Bi-trastuzumab (p=0.461) or the 213Bi-HuIgG (p=0.787).

Table 1.

Median Survival (Days) of Athymic Mice Bearing i.p. LS-174T Xenografts After i.p. Administration of 213Bi-Labeled Monoclonal Antibody and Cisplatin

| Treatment | Days |

|---|---|

| None | 29.5 |

| Cisplatin | 41.5 (1.4) |

| |

Trastuzumab |

HuIgG |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Days | Days |

| RIT | 65 (2.2) | 33 (1.1) |

| Cisplatin 24 hours pre-RIT | 54 (1.8) | 59 (2.0) |

| Cisplatin with RIT | 90.5 (3.1) | 43 (1.5) |

| Cisplatin 24 hours post-RIT | 45 (1.5) | 38 (1.3) |

The values in parentheses are the therapeutic indices (MS of the treatment group divided by the MS of the untreated group).

RIT, radioimmunotherapy; MS, median survival.

FIG. 1.

Effect of cisplatin on therapeutic efficacy of 213Bi-trastuzumab. Athymic mice bearing i.p. LS-174T xenografts were coinjected (i.p.) with cisplatin (▽) and 500 μCi 213Bi-labeled trastuzumab. Groups of mice were coinjected with 213Bi-HuIgG as a nonspecific control, and cisplatin (□). Additional groups were untreated (●), cisplatin (◯), 213Bi-trastuzumab (▼), and 213HuIgG (■).

The mice experienced the greatest weight loss during the first week after treatment with 213Bi. Mice that received 213Bi-trastuzumab or 213Bi-HuIgG showed a weight loss of 5.3% and 5.4%, respectively. A 7.7% weight loss was noted in the group injected with cisplatin alone. The weight loss in the group coinjected with cisplatin and 213Bi-trastuzumab was only 4.9%, whereas cisplatin coinjected with 213Bi-HuIgG resulted in a weight loss of 11.9%. The greatest weight loss was observed in the groups that received cisplatin before (17.6%) or after (16.9%) 213Bi-HuIgG; the weight loss for the groups injected with cisplatin before or after 213Bi-trastuzumab was also high, 10.6% and 10.2%, respectively.

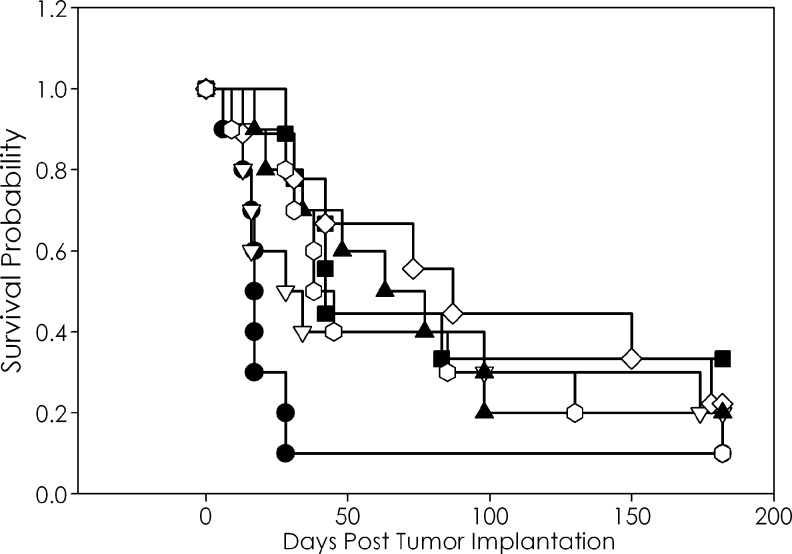

The weight loss experienced by the mice in the above-mentioned experiment was approaching intolerable limits. Further, cisplatin-based therapy induces a number of side effects in cancer patients that include nephrotoxicity, ototoxicity, optic neuropathy, and peripheral neuropathy.26 Carboplatin is a second-generation platinum-based drug developed to lessen the toxicities associated with cisplatin. To this end, the experiment was repeated combining carboplatin with 213Bi RIT. Based on the available reports of carboplatin used in combination with RIT or external-beam irradiation, a dose of 1.25 mg was administered to the mice, a 10-fold greater dose than cisplatin.27,28 Similar to the preceding experiment, the carboplatin exerted a modest therapeutic effect on the LS-174T tumor xenograft with a MS of 28 days versus 17 days for the untreated group (Table 2). Interestingly, the most effective combination of carboplatin with 213Bi-trastuzumab was achieved when the carboplatin was administered 24 hours after the RIT (Fig. 2). This sequence of drug administration resulted in a MS of 87 days, translating to a 5.1-fold increase in survival over the untreated group. The MS of the groups that received the carboplatin preceding or concurrently with 213Bi-trastuzumab was 59 and 66 days, respectively. In this particular experiment, an unusually high MS of 63 days was noted in the group that had received 213Bi-HuIgG.

Table 2.

Median Survival (Days) of Athymic Mice Bearing i.p. LS-174T Xenografts After i.p. Administration of 213Bi-Labeled Monoclonal Antibody and Carboplatin

| Treatment | Days |

|---|---|

| None | 17 |

| Carboplatin | 28 (1.6) |

| |

Trastuzumab |

HuIgG |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Days | Days |

| RIT | 42 (2.5) | 63 (3.7) |

| Carboplatin 24 hours pre-RIT | 66 (3.9) | 60 (3.5) |

| Carboplatin with RIT | 66 (3.9) | 38 (2.2) |

| Carboplatin 24 hours post-RIT | 87 (5.1) | 38 (2.2) |

The values in parentheses are the therapeutic indices (MS of the treatment group divided by the MS of the untreated group).

FIG. 2.

Effect of carboplatin on therapeutic efficacy of 213Bi-trastuzumab. Athymic mice bearing i.p. LS-174T xenografts were injected i.p. with carboplatin 24 hours after the injection of 500 μCi (i.p.) 213Bi-labeled trastuzumab (◊). Another set of mice were injected with 213Bi-HuIgG as a nonspecific control, followed by carboplatin 24 hours later (◯). Additional groups were untreated (●), carboplatin (▽), 213Bi-trastuzumab (■), and 213Bi-HuIgG (▴).

In the group that demonstrated the greatest therapeutic benefit, 213Bi-trastuzumab followed by carboplatin, there was a weight loss of only 4.3%. The greatest weight loss at 1 week again occurred in the groups receiving the carboplatin 24 hours before (7.1%) or after (7.8%) injection of 213Bi-HuIgG. All of the other groups experienced a weight loss that ranged from 3.4% to 5.2%.

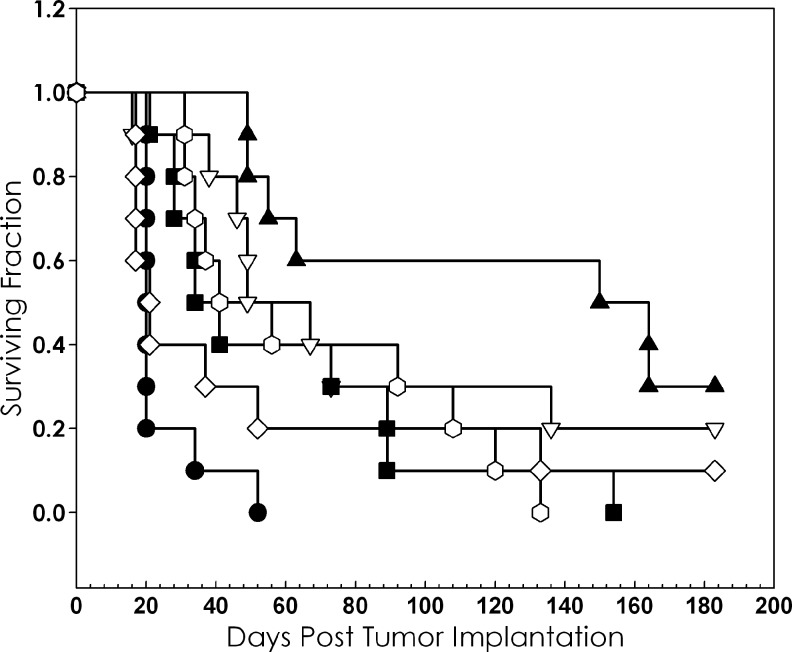

A study was then designed to investigate the effectiveness of multiple doses of carboplatin with 213Bi-trastuzumab. Groups of mice were treated with 500 μCi of 213Bi-trastuzumab and 3 doses of carboplatin (1.25 mg). The first carboplatin dose was given 24–30 hours after the 213Bi-trastuzumab with the 2 subsequent doses given at 7-day intervals. Additional groups received carboplatin only, 213Bi-HuIgG only, 213Bi-HuIgG with 3 doses of carboplatin, or no treatment. As shown in Table 3 and Figure 3, 3-weekly doses of carboplatin after 213Bi-trastuzumab resulted in a significant increase in the MS (186 days) of mice bearing i.p. LS-174T xenografts (p=0.0563). The MS of the untreated group was 21 days; the 3 doses of carboplatin resulted in a therapeutic index of 8.9 and improved the MS of 213Bi-trastuzumab (60 days) by 3.1-fold. No effect on the MS was observed in the groups receiving 3 doses of carboplatin alone (23 days). A comparison between the survival of the group of mice that received 213Bi-trastuzumab was significant compared to the untreated group and those that received 213Bi-HuIgG or carboplatin (p=0.0374).

Table 3.

Efficacy of Multiple Doses of Carboplatin in Combination with a Single Administration of 213Bi Radioimmunotherapy

| |

Carboplatin |

|

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3X | |

| None | 21a | 23 (1.0) |

| 213Bi-Trastuzumab | 60 (2.9) | 186 (8.9) |

| 213Bi-HuIgG | 30 (1.4) | 50 (2.4) |

The values are MS (days).

The values in parentheses are the therapeutic indices (MS of treatment group divided by MS of the untreated group).

FIG. 3.

Efficacy of multiple doses of carboplatin in combination with a single administration of 213Bi-trastuzumab. Athymic mice bearing i.p. LS-174T xenografts were injected i.p. with carboplatin 24 hours after the injection of 500 μCi (i.p.) 213Bi-labeled trastuzumab (◊), which was then followed by 2 additional doses of carboplatin at 1-week intervals (▽). Another set of mice were injected with 213Bi-HuIgG as a nonspecific control, followed by the same dosing with carboplatin (□). Additional groups were untreated (●), 3 doses of carboplatin (◯), 213Bi-trastuzumab (▼), and 213Bi-HuIgG (■).

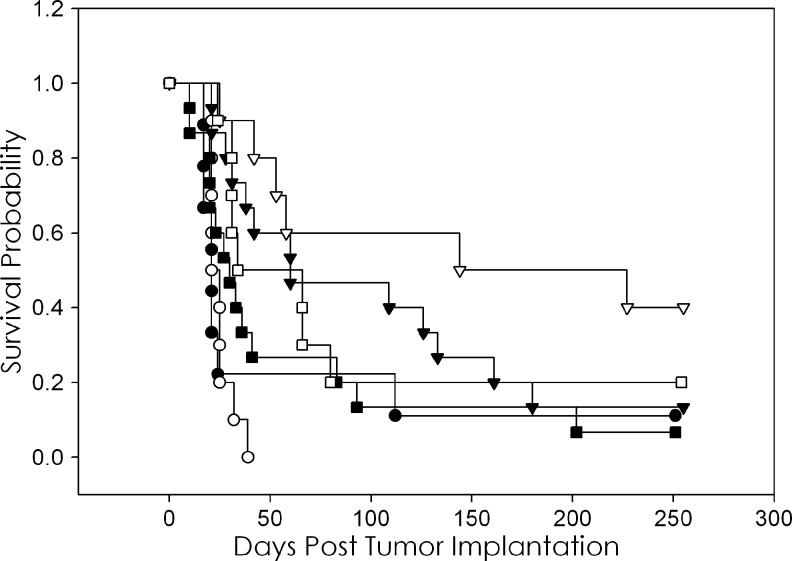

An exploratory study was conducted to assess the potential of combining 212Pb RIT with platinum chemotherapy. Once again, chemotherapy was given 24 hours before, concurrently, or 24 hours after injection of 10 μCi 212Pb-trastuzumab or 212Pb-HuIgG. As with the earlier experiments, other treatment groups included either of the 212Pb-labeled antibodies alone, carboplatin alone, and a group of tumor-bearing mice that was left untreated. Consistent with the 213Bi RIT studies, no therapeutic effect due to the carboplatin was observed (Table 4). Meanwhile, an increase in the therapeutic indices was observed in each of the sequence combinations for carboplatin with 212Pb-trastuzumab. Therapy was enhanced 7.9-fold, 5.8-fold, and 4.1-fold when carboplatin was administered 24 hours pre-, with or 24 hours post-treatment with 212Pb-trastuzumab; MSs were 157, 115, and 82.5 days, respectively. Figure 4 illustrates the Kaplan–Meier survival curves of the group that were pretreated with carboplatin 24 hours before the administration of the 212Pb-trastuzumab. When the experiment was terminated after 183 days, 3 and 4 mice were alive in the groups that received carboplatin 24 hours before or with the 212Pb-trastuzumab, respectively. In spite of these apparent positive results, the timing of the carboplatin in relation to the 212Pb-trastuzumab did not result in significant differences in the MS (p=0.22). Meanwhile, the MS of animals receiving 212Pb-trastuzumab was 49 days, while it was 34 days for 212Pb-HuIgG. Consistent with previous studies from this laboratory, a modest enhancement of therapy was observed in mice that received 212Pb-HuIgG. The highest therapeutic index was 2.1 for the groups that were treated with the carboplatin 24 hours before and 24 hours after the 212Pb-HuIgG.

Table 4.

Median Survival (Days) of Athymic Mice Bearing i.p. LS-174T Xenografts After i.p. Administration of 212Pb-Labeled monoclonal antibody and Carboplatin

| Treatment | Days |

|---|---|

| None | 20 |

| Carboplatin | 21 (1.1) |

| |

Trastuzumab |

HuIgG |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Days | Days |

| RIT | 58 (2.9) | 37.5 (1.9) |

| Carboplatin 24 hours pre-RIT | 157 (7.9) | 35.5 (1.8) |

| Carboplatin with RIT | 115 (5.8) | 42.5 (2.1) |

| Carboplatin 24 hours post-RIT | 82.5 (4.1) | 41 (2.1) |

The values in parentheses are the therapeutic indices (MS of treatment group divided by MS of the untreated group).

FIG. 4.

Effect of carboplatin on therapeutic efficacy of 212Pb-trastuzumab. Athymic mice bearing i.p. LS-174T xenografts were injected i.p. with carboplatin 24 hours before the injection of 10 μCi (i.p.) 212Pb-labeled trastuzumab (▴). Another set of mice were injected with carboplatin, followed by 212Pb-HuIgG, a nonspecific control, 24 hours later (◯). Additional groups were untreated (●), carboplatin (◊), 213Bi-trastuzumab (▽), and 212Pb-HuIgG (■).

Again, the greatest weight loss occurred in the first week after therapy with 212Pb RIT, carboplatin, or the combination. The lowest weight loss (5.5%) was noted in the group of animals that received carboplatin 24 hours before 212Pb-trastuzumab, the group in which the greatest response was observed. In fact, this weight loss was even lower than that of the group that received 212Pb-trastuzumab alone. The highest percent loss was observed in the groups that received carboplatin with the 212Pb-trastuzumab (9.8%) or 24–30 hours after 212Pb-HuIgG (10.0%).

The potentiation of 212Pb-trastuzumab RIT by carboplatin was further investigated. Mice bearing i.p. LS-174T tumor xenografts were pretreated with carboplatin 24 hours before injection of 212Pb-trastuzumab. The mice were injected with BrdU 4 hours before tumor collection that occurred at 6 hours and daily thereafter for 4 days. The tumor tissue was then analyzed for cell cycle distribution and DNA synthesis.

The cell cycle distribution from tumors of mice treated with 212Pb-trastuzumab reveals that there is a decrease in the S-phase with a concomitant increase in the G2/M phase at 24 hours (Table 5). In the group of mice that received the carboplatin and 212Pb-trastuzumab, the shift in the cell cycle distribution is seen to occur at 6 hours. Tumor response to 212Pb-HuIgG alone and in combination with carboplatin follows a similar pattern. Recovery of the cell cycle was evident at 96 hours in tumors treated with 212Pb-HuIgG alone or in combination with carboplatin. Tumors collected from mice treated with 212Pb-trastuzumab and carboplatin do not show any evidence of recovery by the 96-hour time point.

Table 5.

Analysis of Cell Cycle Distribution After Treatment with 212Pb Radioimmunotherapy and Carboplatin

| |

|

|

Timepoint (hours) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RIT | Chemotherapy | Phase | 0 | 6 | 24 | 48 | 72 | 96 |

| None | None | G1 | 72.8±0.6 | |||||

| S | 16.3±0.7 | |||||||

| G2-M | 10.9±1.3 | |||||||

| None | Carboplatin | G1 | 63.6±0.9 | 69.9±1.1 | 65.8±0.6 | 70.8±0.1 | 66.5±3.0 | |

| S | 16.5±1.3 | 17.2±0.2 | 11.6±0.6 | 10.8±0.1 | 12.3±1.5 | |||

| G2-M | 19.9±0.4 | 12.9±1.2 | 22.6±0.1 | 18.4±0.1 | 21.2±1.5 | |||

| Trastuzumab | None | G1 | ND | 74.8±0.9 | 66.4±1.0 | 64.1±0.4 | 61.7±0.1 | |

| S | ND | 11.0±1.0 | 3.7±0.1 | 2.5±0.3 | 5.1±0.3 | |||

| G2-M | ND | 14.2±0.1 | 29.9±0.8 | 33.5±0 | 33.2±0.1 | |||

| Trastuzumab | Carboplatin | G1 | 67.5±2.5 | 74.9±0.4 | 78.2±4.1 | 70.7±1.4 | 65.9±.5 | |

| S | 20.9±0.1 | 5.9±1.5 | 2.6±0.3 | 3.9±0.8 | 4.8±0.3 | |||

| G2-M | 11.6±2.6 | 19.2±1.2 | 19.2±4.4 | 25.4±2.3 | 29.3±0.1 | |||

| HuIgG | None | G1 | ND | 68.0±0.9 | 67.0±1.5 | 71.5±1.5 | 65.4±0.6 | |

| S | ND | 8.1±0.4 | 6.7±1.2 | 5.7±0.2 | 7.7±1.1 | |||

| G2-M | ND | 24.0±0.5 | 26.4±0.3 | 22.9±1.3 | 26.9±0.5 | |||

| HuIgG | Carboplatin | G1 | 68.0±1.2 | 71.7±1.7 | 83.7±1.1 | 63.5±0.6 | 66.9±0.4 | |

| S | 18.8±0.2 | 5.3±0.1 | 3.2±1.2 | 4.5±0.4 | 6.1±0.1 | |||

| G2-M | 13.2±1.3 | 23.0±1.6 | 13.2±0.1 | 32.0±0.9 | 27.1±0.4 | |||

The values presented are the percentage of cells in the G1-, S-, and G2-M phases of the cell cycle along with the standard deviation.

ND, not determined.

Upon analyses of DNA synthesis (Table 6), tumors harvested from untreated mice were found to have a level of synthesis (17.8%) certainly within the expected levels. Consistent with a recent study from this laboratory, DNA synthesis decreased to 9.8% at 24 hours after the administration of 212Pb-trastuzumab, and by 48 hours, DNA synthesis was <1%. At 96 hours, there was no evidence of DNA synthesis recovery. Following the combined treatment of carboplatin and 212Pb-trastuzumab, the decrease in DNA synthesis (3.3%) by 24 hours was more pronounced, and again, there was no evidence of recovery at 96 hours. Tumors taken from mice treated with 212Pb-HuIgG showed the same decrease in DNA synthesis at 24 hours. However, by 72 hours, the DNA synthesis appears to be recovering in this group. In the group of animals that received the carboplatin and 212Pb-HuIgG, the decrease in DNA synthesis is greater, but again, recovery is evident at 96 hours. The carboplatin treatment alone resulted in a gradual decrease in DNA synthesis, occurring over the 96-hour study interval.

Table 6.

Analysis of DNA Synthesis in LS-174 Tumor Xenografts Following Bimodal Treatment with 212Pb Radioimmunotherapy and Carboplatin

| |

|

Timepoint (hours) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RIT | Chemotherapy | 0 | 6 | 24 | 48 | 72 | 96 |

| None | None | 17.8a | |||||

| None | Carboplatin | 17.1 | 16.5 | 14.4 | 13.5 | 8.4 | |

| Trastuzumab | None | ND | 9.8 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.9 | |

| Trastuzumab | Carboplatin | 24.6 | 3.3 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.2 | |

| HuIgG | None | ND | 7.6 | 1.7 | 6.0 | 7.6 | |

| HuIgG | Carboplatin | 15.4 | 4.0 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 5.5 | |

The values presented are the percentage of DNA synthesis determined by flow cytometric analysis for 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine incorporation.

Discussion

The studies reported here represent a systematic exploration of the combination of platinum chemotherapy with α-particle RIT with the objective of increasing the therapeutic efficacy of the RIT. When cisplatin is taken up in a cell, it is activated by aquation and forms DNA adducts.29 Platinum has been shown to bind to the imidazole ring of purine bases, resulting in intra- and interstrand adducts.12,30 The DNA adducts and the associated crosslinking distort DNA and activates repair pathways, ultimately leading to cell death. The platinum–DNA adducts can also interfere with the cellular machinery resulting in cell cycle arrest. Finally, interference with pathways of cell growth, differentiation, and stress responses has also been implicated in the mechanism of action of the platinum-based chemotherapeutic drugs.

Cisplatin has been shown to also serve as a radiosensitizer when used in combination with radiotherapy and is able to sensitize nonhypoxic and hypoxic cells to low radiation doses.31 The cytotoxicity of the platinum drugs clearly differs from paclitaxel and gemcitabine in their mechanisms of action, and as such was chosen for evaluation in combination with RIT.

Interestingly, in spite of the fact that cisplatin has been in use since the early 1970s, and while there are numerous articles describing the combination of platinum drugs with external-beam radiotherapy, there are few studies in which platinum drugs have been combined with RIT and evaluated for in vivo efficacy. Further, these reports are limited to studies that combined cisplatin with 131I or 90Y RIT.13,32 The studies presented here represent the first report of combining platinum drugs with α-particle-emitting radionuclides.

Combination of cisplatin with 213Bi-trastuzumab proved effective in increasing the MS of mice bearing i.p. tumor xenografts by 3.1-fold when the two modalities were coinjected. Mice receiving the 213Bi-trastuzumab experienced an MS of 65 and 90 days when combined with cisplatin. Unfortunately, only 2 of 10 mice remained in the latter group versus 4 of the former group when the study was terminated. Considering the poorer overall survival of the group receiving the combined treatment, attention was shifted to carboplatin, a second-generation platinum drug, with lesser toxicity. In a study of similar design to the one conducted with cisplatin, evaluating the scheduling of the drug and 213Bi RIT, carboplatin was administered 24 hours before, with, or 24 hours after the RIT. In contrast to the cisplatin study, the greatest therapeutic benefit was observed when carboplatin was given 24 hours after the 213Bi-trastuzumab. While the MS of the 213Bi-trastuzumab-only group was 42 days, the carboplatin given the day after RIT resulted in a 2.1-fold increase (87 days) in the MS. These data are consistent with a published report from this laboratory that demonstrated potentiation of the HER2 target 213Bi RIT by paclitaxel; a 6.7-fold and 9.0-fold increase in MS of mice was observed when either 300 or 600 μg of paclitaxel was injected the day after the RIT.4 Additionally, as demonstrated herein, the therapeutic efficacy of RIT was further improved when a total of 3 doses of carboplatin were given following the 213Bi RIT.

The effectiveness of combining carboplatin with targeted α-radiation therapy was found to extend to 212Pb RIT using trastuzumab as the delivery vehicle. In a preliminary experiment, timing of the administration of the carboplatin was found to be the most effective when it was given 24 hours before 212Pb-trastuzumab. Again, these findings are consistent with the above-mentioned publication.4 The importance of empirically determining the administration sequence of RIT and chemotherapy is not a new concept.33,34 In fact, earlier in vitro studies, with four ovarian cell lines and four drugs that included carboplatin, demonstrated clear differences between the drugs and their combination with 90Y RIT. Interestingly, in the hierarchical rating of the four drugs, carboplatin always placed in the worst combination. It must be noted however that carboplatin was most effective when given after the 90Y RIT, the same as the 213Bi RIT studies just discussed. The studies reported herein stress the necessity of determining the administration sequence for each radionuclide. It would not be surprising to find that the delivery vehicle for the target therapy may also exert some influence over the administration sequence of RIT and drug.

The therapeutic efficacy of the radiolabeled HuIgG observed in all of the experiments highlights the requisite of having nonspecific controls. The nonspecific control is needed for several reasons. When a radiolabeled monoclonal antibody (mAb) is injected, binding with the cognate antigen is neither immediate nor may 100% of the injectate be bound. The nonspecific control provides an indicator of the effects of a free circulating and trafficking radioimmunoconjugate. Also, even though trastuzumab has a high affinity for HER2 (Kd=0.1 nM), the antibody–antigen interaction is dynamic, and dissociation does occur.35 Lastly, in the case of an mAb injected into the peritoneum, there is transport of the mAb from the peritoneal cavity that then can be detected in the circulation.36 Again, the nonspecific control provides some measure of the effect of radiation exposure during these processes. Lastly, recent reports from this laboratory have also demonstrated effects of nonspecifically targeted α-radiation at the molecular level.24,37

As of yet, 212Pb RIT exploiting trastuzumab as the targeting vector has demonstrated great potential as a single agent and in combination with chemotherapeutics possessing three distinct modes of action. The relevance of these combined modalities has to cancer patient management is even greater and more poignant. The LS-174T i.p. tumor xenograft is an aggressive model, and its use is well justified.1–4,23 The growth, location, and appearance of the tumor burden mimics that of peritoneal primary or metastatic carcinomas.38

As mentioned in the introduction, the studies generated in this laboratory have been directly translated to a clinical trial at the University of Alabama. The study design of the trial is to assess the safety of i.p. administered 212Pb-TCMC-trastuzumab in patients with HER2-positive peritoneal neoplasms, including those of the ovary, pancreas, stomach, and breast. The studies reported here suggest that there is a potential in combining platinum-based chemotherapeutics with targeted high-LET α-radiation therapy and is a worthwhile endeavor. Combining chemotherapeutics such as paclitaxel, gemcitabine, or carboplatin with 212Pb RIT would be a natural progression to the development of a treatment strategy for cancer patients.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Milenic D. Garmestani K. Brady ED, et al. Targeting of HER2 antigen for the treatment of disseminated peritoneal disease. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:7834. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Milenic DE. Garmestani K. Brady ED, et al. Potentiation of high-let radiation by gemcitabine: Targeting HER2 with trastuzumab to treat disseminated peritoneal disease. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1926. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milenic DE. Garmestani K. Brady ED, et al. Alpha-particle radioimmunotherapy of disseminated peritoneal disease using a (212)Pb-labeled radioimmunoconjugate targeting HER2. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2005;20:557. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2005.20.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milenic DE. Garmestani K. Brady ED, et al. Multimodality therapy: Potentiation of high linear energy transfer radiation with paclitaxel for the treatment of disseminated peritoneal disease. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5108. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simonson RB. Ultee ME. Hauler JA. Alvarez VL. Radioimmunotherapy of peritoneal human colon cancer xenografts with site-specifically modified 212Bi-labeled antibody. Cancer Res. 1990;50:985s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Senekowitsch-Schmidtke R. Schuhmacher C. Becker K-F, et al. Highly specific tumor binding of a 213Bi-labeled monoclonal antibody against mutant e-cadherin suggests its usefulness for locoregional α-radioimmunotherapy of diffuse-type gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andersson H. Lindegren S. Back T, et al. Radioimmunotherapy of nude mice with intraperitoneally growing ovarian cancer xenograft utilizing 211At-labelled monoclonal antibody mov18. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horak E. Hartmann F. Garmestani K, et al. Radioimmunotherapy targeting of HER2/neu oncoprotein on ovarian tumor using lead-212-dota-ae1. J Nucl Med. 1997;38:1944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braakhuis BJ. Ruiz van Haperen VW. Welters MJ. Peters GJ. Schedule-dependent therapeutic efficacy of the combination of gemcitabine and cisplatin in head and neck cancer xenografts. Eur J Cancer. 1995;31A:2335. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00419-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hertel LW. Boder GB. Kroin JS, et al. Evaluation of the antitumor activity of gemcitabine (2′,2′-difluoro-2′-deoxycytidine) Cancer Res. 1990;50:4417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toschi L. Finocchiaro G. Bartolini S, et al. Role of gemcitabine in cancer therapy. Future Oncol. 2005;1:7. doi: 10.1517/14796694.1.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelland L. The resurgence of platinum-based cancer chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:573. doi: 10.1038/nrc2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shikani AH. Richtsmeier WJ. Klein JL. Kopher KA. Radiolabeled antibody therapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:521. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1992.01880050075018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tom BH. Rutzky LH. Jakstys MH. Human colonic adenocarcinoma cells. Establishment and description of a new cell line. In Vitro. 1976;12:180. doi: 10.1007/BF02796440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu F. Yu Y. Le XF, et al. The outcome of heregulin-induced activation of ovarian cancer cells depends on the relative levels of her-2 and her-3 expression. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:3653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brechbiel MW. Gansow OA. Synthesis of c-functionalized trans-cyclohexyldiethylene-triamine-pentaacetic acids for labelling of monoclonal antibodies with the bismuth-212 α-particle emitter. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans. 1992;1:1173. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chappell LL. Dadachova E. Milenic DE, et al. Synthesis, characterization, and evaluation of a novel bifunctional chelating agent for the lead isotopes 203Pb and 212Pb. Nucl Med Biol. 2000;27:93. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(99)00086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowry OH. Rosebrough NJ. Farr AL. Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pippin CG. Parker TA. McMurry TJ. Brechbiel MW. Spectrophotometric method for the determination of a bifunctional dtpa ligand in dtpa-monoclonal antibody conjugates. Bioconjug Chem. 1992;3:342. doi: 10.1021/bc00016a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dadachova E. Chappell LL. Brechbiel MW. Spectrophotometric method for determination of bifunctional macrocyclic ligands in macrocyclic ligand-protein conjugates. Nucl Med Biol. 1999;26:977. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(99)00054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milenic DE. Garmestani K. Dadachova E, et al. Radioimmunotherapy of human colon carcinoma xenografts using a 213Bi-labeled domain-deleted humanized monoclonal antibody. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2004;19:135. doi: 10.1089/108497804323071904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu H. Baidoo K. Gunn AJ, et al. Design, synthesis, and characterization of a dual modality positron emission tomography and fluorescence imaging agent for monoclonal antibody tumor-targeted imaging. J Med Chem. 2007;50:4759. doi: 10.1021/jm070657w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buchsbaum DJ. Rogers BE. Khazaeli MB, et al. Targeting strategies for cancer radiotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:3048s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yong KJ. Milenic DE. Baidoo KE. Brechbiel MW. (212)Pb-radioimmunotherapy induces g(2) cell-cycle arrest and delays DNA damage repair in tumor xenografts in a model for disseminated intraperitoneal disease. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:639. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gregoire V. Van NT. Stephens LC, et al. The role of fludarabine-induced apoptosis and cell cycle synchronization in enhanced murine tumor radiation response in vivo. Cancer Res. 1994;54:6201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loehrer PJ. Einhorn LH. Drugs five years later. Cisplatin. Ann Intern Med. 1984;100:704. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-100-5-704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aratani Y. Yoshiga K. Mizuuchi H, et al. Antitumor effect of carboplatin combined with radiation on tumors in mice. Anticancer Res. 1997;17:2535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hartley C. Elliott S. Begley CG, et al. Kinetics of haematopoietic recovery after dose-intensive chemo/radiotherapy in mice: Optimized erythroid support with darbepoetin alpha. Br J Haematol. 2003;122:623. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farrell NP. Preclinical perspectives on the use of platinum compounds in cancer chemotherapy. Semin Oncol. 2004;31:1. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siddik ZH. Cisplatin: Mode of cytotoxic action and molecular basis of resistance. Oncogene. 2003;22:7265. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blumenthal RD. Sharkey RM. Natale AM, et al. Comparison of equitoxic radioimmunotherapy and chemotherapy in the treatment of human colonic cancer xenografts. Cancer Res. 1994;54:142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kievit E. Pinedo HM. Schluper HM. Boven E. Addition of cisplatin improves efficacy of 131I-labeled monoclonal antibody 323/a3 in experimental human ovarian cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;38:419. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)82501-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blumenthal RD. Leone E. Goldenberg DM. Tumor-specific dose scheduling of bimodal radioimmunotherapy and chemotherapy. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:4613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blumenthal RD. Leone E. Goldenberg DM, et al. An in vitro model to optimize dose scheduling of multimodal radioimmunotherapy and chemotherapy: Effects of p53 expression. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:293. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldenberg MM. Trastuzumab, a recombinant DNA-derived humanized monoclonal antibody, a novel agent for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Clin Ther. 1999;21:309. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(00)88288-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Milenic DE. Wong KJ. Baidoo KE, et al. Targeting HER2: A report on the in vitro and in vivo pre-clinical data supporting trastuzumab as a radioimmunoconjugate for clinical trials. MAbs. 2010;2:550. doi: 10.4161/mabs.2.5.13054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yong KJ. Milenic DE. Baidoo KE. Brechbiel MW. Sensitization of tumor to (212)Pb radioimmunotherapy by gemcitabine involves initial abrogation of G2 arrest and blocked DNA damage repair by interference with rad51. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;267:173. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levy AD. Shaw JC. Sobin LH. Secondary tumors and tumorlike lesions of the peritoneal cavity: Imaging features with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2009;29:347. doi: 10.1148/rg.292085189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]