Abstract

Introduction

Gastric bypass surgery in rats has been shown to mimic the weight loss pattern seen in humans. The aim of this study was to evaluate whether two variations of the technique to create the gastric pouch resulted in a different outcome regarding body weight and food intake.

Material and Methods

Male Wistar rats underwent either gastric bypass (n=55) or sham-operation (n=27). In Group 1 the complete paraoesophageal neurovascular bundle including the dorsal vagal trunk and the left gastric vessels was completely ligated in all gastric bypass rats (n=17). In Group 2 the left gastric vessels were separated and selectively ligated while the paraoesophageal bundle itself was preserved in all gastric bypass rats (n=10), In Group 3 gastric bypass rats (n=28) were randomized for either one of the two techniques described above. Body weight and food intake of gastric bypass rats were compared to sham-operated controls in all three groups.

Results

Overall surgical mortality was 13.4% (11/82). Over an observation period of 60 days there was no difference in daily energy intake between gastric bypass rats and sham-operated rats in group 1 (sham: 97.4 ± 2.5 kcal vs. bypass: 89.3 ± 4.7 kcal, p=0.3), while gastric bypass rats in group 2 ate significantly less than their sham-operated counterparts (sham: 76.7 ± 2.2 kcal vs. bypass 52.5 ± 4.8 kcal, p<0.001). In group 3, gastric bypass rats with selectively ligated left gastric vessels showed a lower food intake than sham controls and bypass rats whose paraoesophageal bundle was completely ligated (sham: 118.7 ± 3.9 kcal vs. bypass with selective ligation: 85.5 ± 2.2 kcal vs. bypass with complete ligation 98.6 ± 2.8 kcal, p<0.001). Similar differences were observed for body weight with gastric bypass rats with a selective ligation of the left gastric vessels having the lowest body weight in comparison to sham controls and bypass rats whose paraoesophageal bundle was completely ligated (group 3 (day 75): sham: 608.1 ± 7.0g vs. bypass with selective ligation: 365.8 ± 14.6 vs. bypass with complete ligation: 468.0 ± 9.3 g, p<0.001). Differences in food intake and body weight were not related to the size of the gastro-jejunostomy in gastric bypass rats of group 3. There were no signs of malabsorption or inflammation after gastric bypass in any of the groups.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our gastric bypass technique induces reliable weight loss in rats with an acceptable mortality. We propose that the left gastric vessels should be selectively ligated during the operation as this might play an important role for the mechanisms that induce weight loss and reduce food intake after gastric bypass in rats. In contrast, the gastro-jejunal stoma size was found to be of minor relevance.

Keywords: gastric bypass, rats, paraoesophageal bundle, vagal nerve, left gastric vessels, weight loss

Introduction

The obesity epidemic is a major health concern that is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. The personal, social, and economic consequences can be devastating [1-3]. So far, bariatric surgery has been proven to be the most effective treatment for severe obesity and its inherent co-morbidities resulting in significant and sustained weight loss with a proven mortality benefit [4,5]. At present, the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedure (gastric bypass) provides reliable and sustainable weight loss. Given the rapid increase in gastric bypass procedures, it is important to understand the underlying mechanisms by which gastric bypass induces and sustains weight loss [6]. The use of animal models for gastric bypass surgery is a valuable tool and has been shown to be a valid model to mimic human weight loss after gastric bypass [7-10]. However, there is a great variety in different techniques being used and results in weight loss and food intake as well as mortality rates are heterogeneous [7,8,11-18]. Herein, we describe variations in the technique for gastric bypass surgery in rats in the area of the gastro-jejunostomy. The aim was to assess whether different techniques in handling the paraesophageal bundle resulted in different outcome regarding body weight and food intake.

Material and Methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats used were individually housed under a 12h/12h light-dark cycle and at a room temperature of 21 ± 2 °C. Water and standard chow were available ad libitum, unless otherwise stated. All experiments were performed under a license issued by the Home Office UK (PL 70-5569) or approved by the Veterinary Office of the Canton Zurich, Switzerland. Body weight and food intake were measured daily in group 1 and 2 for a postoperative period of 60 days and in group 3 for 75 days.

Surgery

All operations reported in this study were performed by one surgeon (MB). Prior to the start of the experiments the surgeon practiced the procedure on 60 cadaveric rats which resulted in the following surgical protocol.

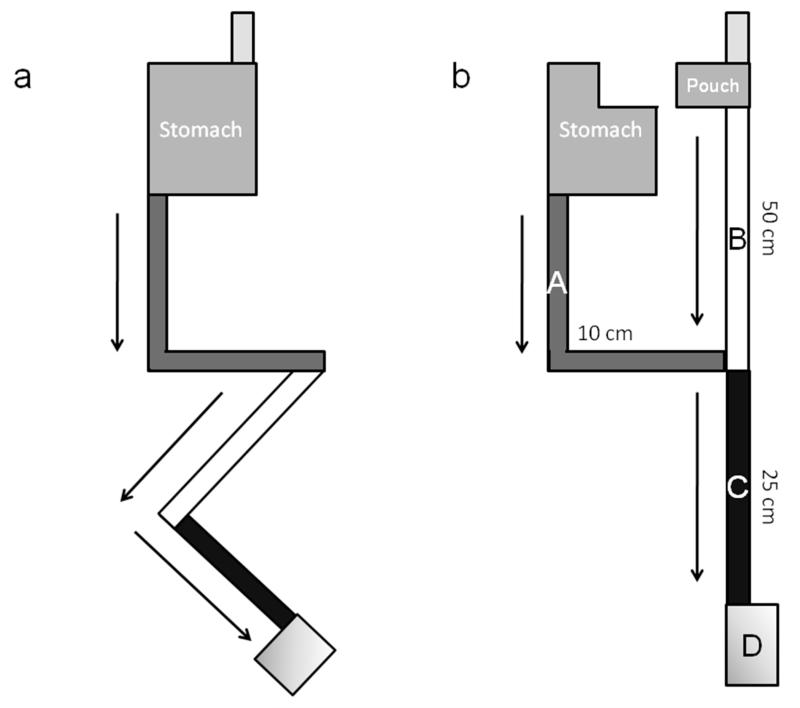

After 1 week of acclimatization rats were randomized to gastric bypass or sham operation. Rats were fasted overnight with water available ad libitum. Before surgery, rats were weighed, and then anesthetized with isofluorane (4% for induction, 3% for maintenance). Preoperatively, gentamicin 8 mg/kg and carprofen 0.01 ml were administered intraperitoneally (ip) as prophylaxis for postoperative infection and pain relief. Surgery was performed on a heating pad to avoid decrease of body temperature during the procedure. Prior to a midline laparotomy, the abdomen was shaved and disinfected with surgical scrub. In the sham group a 7 mm gastrotomy on the anterior wall of the stomach with subsequent closure (interrupted prolene 5-0 sutures) and a 7 mm jejunotomy with subsequent closure (running prolene 6-0 suture) was performed. In the gastric bypass group, the proximal jejunum was divided 15 cm distal to the pylorus to create a biliopancreatic limb (Figure 1, A). After identification of the caecum (Figure 1, D), the ileum was then followed proximally to create a common channel of 25 cm (Figure 1, C). Here, a 7 mm side-to-side Jejuno-Jejunostomy (running prolene 7-0 suture) between the biliopancreatic limb and the common channel was performed.

Figure 1.

Diagrammatic representation of the gastrointestinal anatomy before (a) and after (b) the gastric bypass operation.(A) Biliopancreatic limb (~10 cm), (B) Alimentary limb (~50 cm), (C) Common channel (~25 cm), (D) Coecum.

The two techniques described below in this paper relates to how the stomach was transected close to the gastro-oesophageal junction to create a small gastric pouch with no more than 3 mm of gastric mucosa left. The gastric pouch and alimentary limb was anastomosed (Figure 1, B) end-to side using a running prolene 7-0 suture. The gastric remnant was closed with interrupted prolene 5-0 sutures. The complete bypass procedure lasted approximately 60 minutes and the abdominal wall was closed in layers using 4-0 and 5-0 prolene sutures. Approximately 20 minutes before the anticipated end of general anesthesia, all rats were injected with 0.1 ml of 0.3% buprenorphine subcutaneously to minimize postoperative discomfort. Immediately after abdominal closure, all rats were injected subcutaneously with 5 ml of normal saline to compensate for intraoperative fluid loss. After 24 hours of wet diet (= normal chow soaked in tap water), regular chow was offered on postoperative day 2. Figure 1 shows a schematic illustration of the intestinal anatomy before and after gastric bypass surgery.

Experimental design

Within the development of our standard technique, two different techniques were used to control large blood vessels in the area of the gastric pouch. All groups were operated in chronological order. In a first group, 25 rats (Body weight (BW) 348±3.9g) were randomized for gastric bypass (n = 17) or sham operation (n = 8). In this group the paraoesophageal neurovascular bundle including the dorsal vagal trunk and the left gastric vessels was completely ligated in all gastric bypass rats (Group 1). In a subsequent group, 18 rats (332±2.4g) were randomized for gastric bypass (n=10) or sham operation (n=8). Due to the increasing experience of the surgeon the procedure was performed much less traumatic than before. Thus, the left gastric vessels were separated and selectively ligated in all gastric bypass rats, while the paraoesophageal neurovascular bundle itself was preserved (Group 2). Significant differences in body weight and energy intake were observed in these two groups. As it was unclear whether these differences were related to the different techniques as described above, a third group of 39 rats (471±4.3g) was randomized for gastric bypass with complete ligation of the paraoesophageal bundle (n=14) or gastric bypass with selective ligation of the left gastric vessels (n=14) or sham operation (n=11, Group 3).

Measurement of size of the gastrojejunostomy

To exclude that the differences in body weight between bypass rats were due to different levels of restriction and subsequent differences in food intake, sizes of the gastro-jejunostomy were measured during necropsy in all gastric bypass rats of group 3.

Blood analysis

Blood was obtained from all animals of group 3 by puncture of a sublingual vein under brief isoflurane anesthesia. Blood was collected into EDTA-rinsed tubes and immediately centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. Plasma was stored at −80°C before analysis for C-reactive protein (Abbott, UK) to assess inflammation.

Faecal analysis

To evaluate nutrient malabsorption, faeces were collected over 24 h on postoperative days 15 and 59 from all animals in group 3. Faeces were dried in an oven and weighed; calorie content was measured using a ballistic bomb calorimeter [19].

Statistics

All data were normally distributed and are expressed as mean ± SEM. Student’s t-test for independent samples and one-way ANOVA with repeated measures and post-hoc Bonferroni test for each time point were used to test for significant differences. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Mortality

Overall surgical mortality was 13.4% (11/82). Gastric bypass-related mortality was 14.5% (8/55), while mortality after sham-operation was 11.1% (3/27). There was no mortality difference between bypass rats with complete ligation and with preservation of the paraoesophageal bundle. Table 1 shows the procedure-related number of deaths for Groups 1 to 3 as indicated in chronological order of the cases performed. All eight bypass rats showed signs of respiratory distress along with hypersalivation and dysphagia within the first two postoperative days after the operation and were euthanized immediately after onset of symptoms. Necropsy revealed that these symptoms originated at the level of the gastro-jejunostomy where food did not pass through and was retained in the oesophagus. Whether this was due to inflammatory swelling following anastomotic leakage or due to anastomotic constriction remains unclear. The three sham-operated rats died without prior noticeable symptoms. Necropsy revealed in two cases a small bowel ileus presumably due to a volvulus after inappropriate repositioning of the viscera into the abdominal cavity at the end of the operation. In one case a leak at the site of the gastrotomy was found.

Table 1.

Procedure-related number of deaths for Groups 1 to 3 as indicated in chronological order of the cases performed.

| Case number | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bypass (n=17) | Sham (n=8) | Bypass (n=10) | Sham (n=8) | Bypass (n=28) | Sham (n=11) | |

| 1 – 10 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| 11 – 20 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||

| 21 – 30 | 1 | |||||

Energy intake

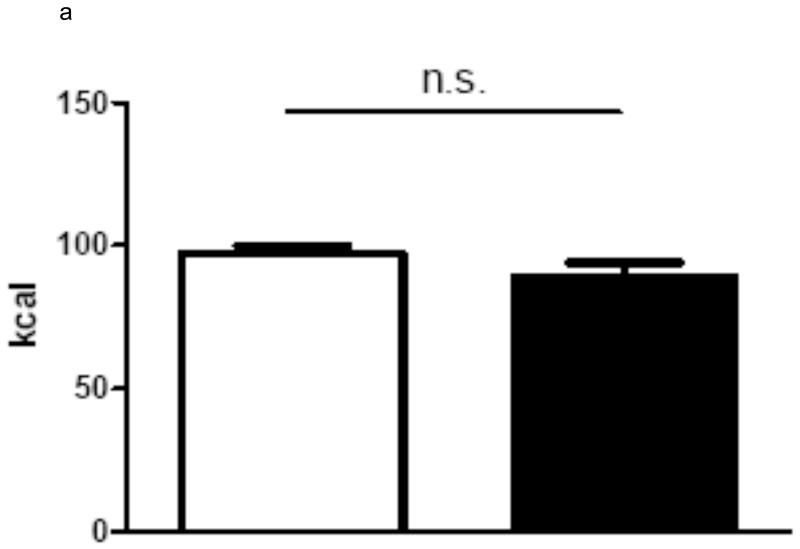

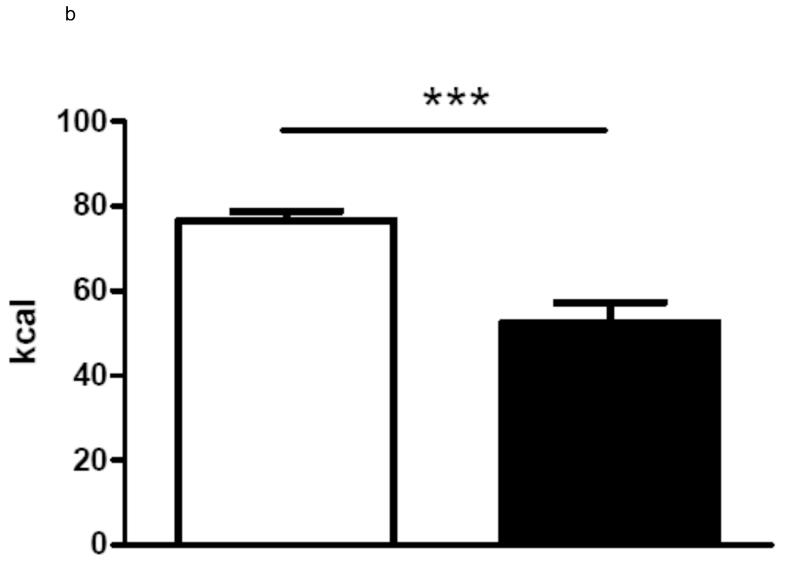

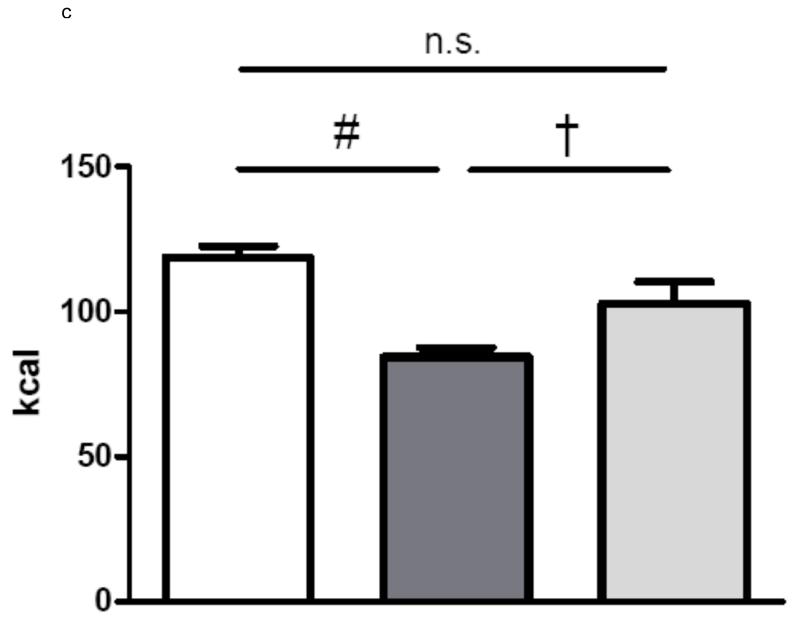

In group 1 with complete paraoesophageal neurovascular bundle ligation there was no difference in average daily energy intake between gastric bypass rats and sham-operated rats over a period of 60 days (sham: 97.4 ± 2.5 kcal vs. bypass: 89.3 ± 4.7 kcal, p=0.3). In contrast, rats of group 2 with preserved paraoesophageal neurovascular bundle ate significantly less than the sham-operated rats (sham: 76.7 ± 2.2 kcal vs. bypass 52.5 ± 4.8 kcal, p<0.001). In group 3, there was no difference in average energy intake between bypass rats with complete paraoesophageal bundle ligation and sham-operated rats over a period of 75 days, while rats with a preserved paraoesophageal bundle ate significantly less than sham-operated rats and rats with complete paraoesophageal bundle ligation (sham: 118.7 ± 3.9 kcal vs. Bypass with preserved paraoesophageal bundle: 84.4 ± 3.3 kcal vs. Bypass with complete paraoesophageal bundle ligation 102.8 ± 7.5 kcal, p<0.001). The average daily energy intake is shown for all three groups in figures 2.

Figure 2.

a Average daily energy intake (Group 1) over 60 days for sham-operated ad libitum fed rats (n=7, white column) and for gastric bypass rats (n=14, black column). Data are shown as mean values ± SEM.

b Average daily energy intake (Group 2) over 60 days for sham-operated ad libitum fed rats (n=8, white column) and for gastric bypass rats (n=8, black column). Data are shown as mean values ± SEM (*** = p<0.001).

c Average daily energy intake (Group 3) over 75 days for sham-operated ad libitum fed rats (n=10, white column) and for gastric bypass rats with selective ligation of the left gastric arterie (n=11, dark grey) or with complete ligation of the paraoesophageal bundle (n=10, light grey). Data are shown as mean values ± SEM. Post-hoc differences between the 3 groups are indicated (# = p<0.001 and † = p<0.05).

Body weight

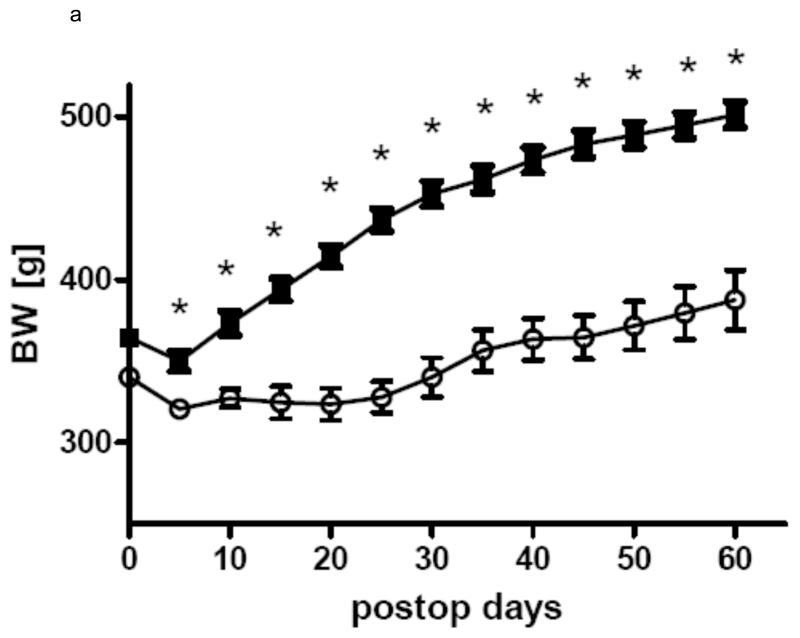

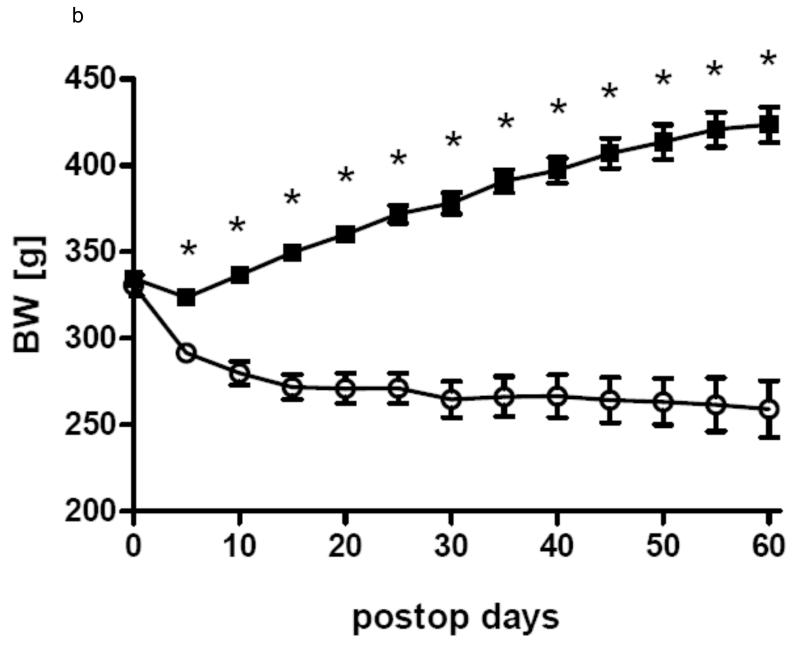

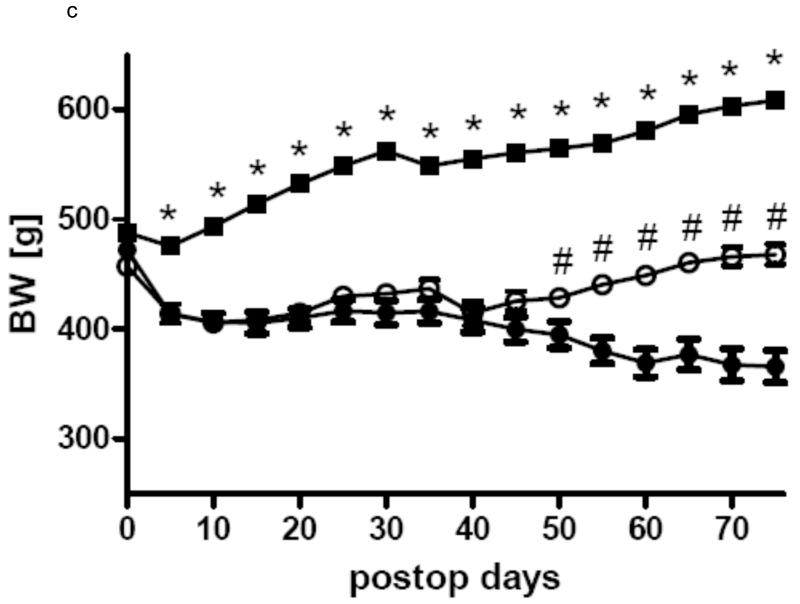

In all three groups gastric bypass rats had a significant lower body weight than sham-operated rats from day 5 after surgery throughout the rest of the observation period. After a short period of post surgical weight loss, sham-operated rats of all three groups constantly gained weight for the rest of the study. In Group 1 gastric bypass rats with complete paraoesophageal bundle ligation started to regain weight around postoperative day 25 and there was no difference between their body weight before surgery and after surgery at the end of the observation period (day 0: 457.0 ± 7.4 g vs. day 60: 468.0 ± 9.3 g, p=0.36). In group 2, gastric bypass animals with preserved paraoesophageal bundle lost about 20% of their preoperative weight by postoperative day 25 and their body weight then plateaued around 260 g (day 0: 330.8 ± 5.8 g vs. day 60: 259.1 ± 16.3 g, p=0.001). In group 3, there was no difference in body weight between bypass rats with complete paraoesophageal bundle ligation and bypass rats with preserved paraoesophageal bundle until postoperative day 40 (day 40: bypass with preserved paraoesophageal bundle: 408.3 ± 11.2 vs. bypass with complete paraoesophageal ligation: 414.4 ± 11.2 g, p=0.70). However, thereafter bypass rats with a complete paraoesophageal ligation started to regain weight for the rest of the observation period, while bypass rats with preserved paraoesophageal bundle maintained their low body weight (day 75: bypass with selective ligation: 365.8 ± 14.6 vs. bypass with complete ligation: 468.0 ± 9.3 g, p<0.001). The development of body weight after surgery is shown for all groups in figures 3.

Figure 3.

a Body weight change in group 1 for the gastric bypass (-o-) (n=14) and sham-operated rats (-■-)(n=7). Data are shown as mean values ± SEM (* = p<0.05).

b Body weight change in group 2 for the gastric bypass (-o-) (n=8) and sham-operated rats (-■-)(n=8). Data are shown as mean values ± SEM (* = p<0.05).

c Body weight change in group 3 for the gastric bypass rats with complete ligation of the paraoesophageal neurovascular bundle (-o-) (n=10) and gastric bypass rats with selective ligation of the left gastric arterie (-●-) (n=11) and sham-operated rats (-■-)(n=10). Data are shown as mean values ± SEM (* = p<0.05 for sham vs. bypass; # = p<0.05 for bypass with complete ligation vs. bypass with selective ligation).

Size of the gastro-jejunostomy

There was no gastrogastric fistula in any of the gastric bypass rats of group 3. The overall size of the gastro-jejunostomy in all gastric bypass rats was 15.4 ± 0.4 mm. There was no difference in size of the anastomosis between rats in which the complete paraoesophageal bundle was ligated and rats in which the left gastric vessels were separated and selectively ligated (bypass with selective ligation: 15.2 ± 0.4 mm vs. 15.6 ± 0.7 mm, p=0.69).

Blood analysis

C-reactive protein levels were below 2mg/L in all animals of group 3 indicating that there was no postsurgical infection or inflammation 28 days after surgery.

Faecal analysis

There was no increase in either fresh faecal mass (sham: 8.4 ± 0.5 g vs. Bypass with preserved paraoesophageal bundle: 7.5 ± 0.6 g vs. Bypass with complete paraoesophageal bundle ligation 7.2 ± 0.6 g, p=0.3) or faecal calorie content (sham: 3.56 ± 0.04 kcal vs. Bypass with preserved paraoesophageal bundle: 3.43 ± 0.05 kcal vs. Bypass with complete paraoesophageal bundle ligation 3.65 ± 0.06 kcal, p=0.24) in the gastric bypass animals compared to the sham-operated rats in group 3.

Discussion

Our data in the rat model for gastric bypass are consistent with previous findings that gastric bypass surgery can effectively induce food intake and body weight reduction [4,9,20,21]. In this randomized study the weight loss and food intake outcome of gastric bypass surgery was dependent on whether the paraoesophageal neurovascular bundle was completely ligated or not. Rats in which the bundle was completely ligated started to regain body weight up to preoperative levels and showed no difference in average daily energy intake compared to their sham-operated counterparts. In contrast, rats in which the paraoesophageal bundle was preserved and in which the left gastric vessels were selectively ligated, maintained the reduced body weight and ate significantly less than the sham-operated controls throughout the entire study period.

It is known that gastric bypass increases postprandial levels of peptide YY (PYY) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), which are satiation inducing gut hormones and hence favour an anorectic state and facilitate body weight loss [7]. Both hormones are thought to activate anorectic neurons in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (ARC) which promote weight loss [22-25]. Interestingly, the inhibitory effects of PYY and GLP-1 on food intake are attenuated by ablation of the vagal-brainstem-hypothalamic pathway indicating an important role of the vagal nerve for mediating their effects on food intake and energy expenditure [26].

The paraoesophageal bundle with the dorsal vagal trunk consists of about 4/5 right vagal fibres and about 1/5 left vagal fibres and the left gastric vessels [27]. Thus, we cannot exclude the possibility that the ligation of this bundle is functionally equivalent to a partial dissection of the vagal nerve. Our data suggest that the vagal nerve may play an important role for the outcome after gastric bypass surgery in rats. However, we did not perform a secretin test or histological analysis to further confirm whether the complete ligation of the paraoesophageal bundle produced a total or partial vagotomy.

In contrast to our observation, a greater long-term weight loss has been recently described after total vagal dissection along with a gastric bypass operation in rats [18]. In this study the bypassed jejunum was about 10 cm in length which is much less in comparison to our technique as described above. This variation in length of the bypassed jejunum may result in differences in GLP-1 and PYY levels which may result in altered long-term body weight loss.

Mortality rates for gastric bypass models in rats are rarely reported and range from 0% to 30% [7,8,11-18]. Thus, our rate is within the reported range. The postoperative diets used after gastric bypass in rats also vary [7,8,11-18]. Especially the duration and the need of a liquid diet after the operation are controversial [7,8,11-18]. In our study regular chow was offered on postoperative day two after one day of a wet diet (normal chow soaked in tap water). This might have been too early as the majority of rats that had to be euthanized after gastric bypass showed symptoms of esophageal food impaction.

Weight loss after a gastric bypass operation might also be due to nutrient malabsorption or postoperative inflammation. However, we found no evidence for an increase in either fecal mass or fecal calorie content in the gastric bypass animals. Moreover we did not detect any evidence of increased inflammation in animals post surgery.

The size of the gastric pouch and the lengths of the different limbs used in this study have been proven to effectively induce weight loss [7,9]. An increasing body of evidence in humans indicates that up to certain limits the size of the gastric pouch and length of the different limbs is of less importance for the outcome of gastric bypass [28]. In support of this observation, we demonstrated that the level of restriction measured by the size of the gastro-jejunostomy has no impact on different levels of weight loss and food intake after gastric bypass in rats.

In conclusion, our gastric bypass technique induces reliable weight loss in rats with an acceptable mortality. Restriction at the gastro-jejunal anastomosis does not seem to be critical for the weight loss. We propose that the left gastric vessels should be selectively ligated to preserve the paraoesophageal bundle which contains vagal nerve fibres as it might play an important role in inducing and maintaining weight loss after gastric bypass in rats.

Acknowledgements

M. B. was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG). T.L. and C.L. were supported by the Swiss National Research Foundation. S.B. and C.le R. were supported by a Department of Health Clinician scientist award. Imperial College London receives support from the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre funding scheme.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Allison DB, Saunders SE. Obesity in North America. An overview. Med Clin North Am. 2000;84:305–32. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70223-6. v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hedley AA, Ogden CL, Johnson CL, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999-2002. JAMA. 2004;291:2847–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.23.2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Visscher TL, Seidell JC. The public health impact of obesity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2001;22:355–75. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.22.1.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adams TD, Gress RE, Smith SC, et al. Long-term mortality after gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:753–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724–37. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borg CM, le Roux CW, Ghatei MA, et al. Progressive rise in gut hormone levels after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass suggests gut adaptation and explains altered satiety. Br J Surg. 2006;93:210–5. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guijarro A, Suzuki S, Chen C, et al. Characterization of weight loss and weight regain mechanisms after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R1474–R1489. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00171.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.le Roux CW, Aylwin SJ, Batterham RL, et al. Gut hormone profiles following bariatric surgery favor an anorectic state, facilitate weight loss, and improve metabolic parameters. Ann Surg. 2006;243:108–14. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000183349.16877.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.le Roux CW, Welbourn R, Werling M, et al. Gut hormones as mediators of appetite and weight loss after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Ann Surg. 2007;246:780–5. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3180caa3e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furnes MW, Stenstrom B, Tommeras K, et al. Feeding behavior in rats subjected to gastrectomy or gastric bypass surgery. Eur Surg Res. 2008;40:279–88. doi: 10.1159/000114966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furnes MW, Tommeras K, Arum CJ, et al. Gastric bypass surgery causes body weight loss without reducing food intake in rats. Obes Surg. 2008;18:415–22. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9392-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guijarro A, Osei-Hyiaman D, Harvey-White J, et al. Sustained weight loss after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is characterized by down regulation of endocannabinoids and mitochondrial function. Ann Surg. 2008;247:779–90. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318166fd5f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meguid MM, Glade MJ, Middleton FA. Weight regain after Roux-en-Y: a significant 20% complication related to PYY. Nutrition. 2008;24:832–42. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2008.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stenstrom B, Furnes MW, Tommeras K, et al. Mechanism of gastric bypass-induced body weight loss: one-year follow-up after micro-gastric bypass in rats. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:1384–91. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stylopoulos N, Davis P, Pettit JD, et al. Changes in serum ghrelin predict weight loss after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in rats. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:942–6. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-8825-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tichansky DS, Boughter JD, Jr., Harper J, et al. Gastric bypass surgery in rats produces weight loss modeling after human gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2008;18:1246–50. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9556-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Liu J. Combination of Bypassing Stomach and Vagus Dissection in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Rats-A Long-Term Investigation. Obes Surg. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9862-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackson RJ, Davis WB, Macdonald I. The energy values of carbohydrates: should bomb calorimeter data be modified? Proc Nutr Soc. 1977;36:90A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korner J, Bessler M, Cirilo LJ, et al. Effects of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery on fasting and postprandial concentrations of plasma ghrelin, peptide YY, and insulin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:359–65. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubino F, Gagner M, Gentileschi P, et al. The early effect of the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on hormones involved in body weight regulation and glucose metabolism. Ann Surg. 2004;240:236–42. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133117.12646.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Batterham RL, Cowley MA, Small CJ, et al. Gut hormone PYY(3-36) physiologically inhibits food intake. Nature. 2002;418:650–4. doi: 10.1038/nature00887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Batterham RL, Cohen MA, Ellis SM, et al. Inhibition of food intake in obese subjects by peptide YY3-36. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:941–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cone RD, Cowley MA, Butler AA, et al. The arcuate nucleus as a conduit for diverse signals relevant to energy homeostasis. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25(Suppl 5):S63–S67. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larsen PJ, Tang-Christensen M, Jessop DS. Central administration of glucagon-like peptide-1 activates hypothalamic neuroendocrine neurons in the rat. Endocrinology. 1997;138:4445–55. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.10.5270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abbott CR, Monteiro M, Small CJ, et al. The inhibitory effects of peripheral administration of peptide YY(3-36) and glucagon-like peptide-1 on food intake are attenuated by ablation of the vagal-brainstem-hypothalamic pathway. Brain Res. 2005;1044:127–31. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niederhausern W.v. Recherches experimentales sur la fasciculation et la terminaison des nerfs vagues dans l’abdomen et leurs rapports avec l’innervation renale chez le rat. C.R.Assoc.Anat. 1953;40:783–784. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muller MK, Rader S, Wildi S, et al. Long-term follow-up of proximal versus distal laparoscopic gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Br J Surg. 2008;95:1375–9. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]