Abstract

Estimates of the prevalence of Shigella spp. are limited by the suboptimal sensitivity of current diagnostic and surveillance methods. We used a quantitative PCR (qPCR) assay to detect Shigella in the stool samples of 3,533 children aged <59 months from the Gambia, Mali, Kenya, and Bangladesh, with or without moderate-to-severe diarrhea (MSD). We compared the results from conventional culture to those from qPCR for the Shigella ipaH gene. Using MSD as the reference standard, we determined the optimal cutpoint to be 2.9 × 104 ipaH copies per 100 ng of stool DNA for set 1 (n = 877). One hundred fifty-eight (18%) specimens yielded >2.9 × 104 ipaH copies. Ninety (10%) specimens were positive by traditional culture for Shigella. Individuals with ≥2.9 × 104 ipaH copies have 5.6-times-higher odds of having diarrhea than those with <2.9 × 104 ipaH copies (95% confidence interval, 3.7 to 8.5; P < 0.0001). Nearly identical results were found using an independent set of samples. qPCR detected 155 additional MSD cases with high copy numbers of ipaH, a 90% increase from the 172 cases detected by culture in both samples. Among a subset (n = 2,874) comprising MSD cases and their age-, gender-, and location-matched controls, the fraction of MSD cases that were attributable to Shigella infection increased from 9.6% (n = 129) for culture to 17.6% (n = 262) for qPCR when employing our cutpoint. We suggest that qPCR with a cutpoint of approximately 1.4 × 104 ipaH copies be the new reference standard for the detection and diagnosis of shigellosis in children in low-income countries. The acceptance of this new standard would substantially increase the fraction of MSD cases that are attributable to Shigella.

INTRODUCTION

Shigella spp. are among the most common causes of moderate-to-severe diarrhea (MSD) worldwide, disproportionately affecting children <5 years of age living in developing countries (1). Estimates of Shigella incidence are limited by inconsistent diagnostic accuracy and inaccurate surveillance methods. The current gold standard for the detection of Shigella species in fecal specimens requires isolation, growth, and identification in culture. Though the methods were developed in the first half of the 20th century, they require considerable operator training and expertise, both of which are often unavailable at the sites of greatest disease burden. Moreover, even in experienced hands, the cultivation of Shigella spp. is impeded by inconsistent bacterial load, loss of bacterial viability during specimen transport and storage, and requirements for specific reagents that are labile and sometimes unavailable (2). Nevertheless, advantages of cultivation are its validation and verification of a bacterium's identity and its availability for downstream characterization.

Some studies have shown that the detection of Shigella using DNA amplification techniques might suggest an increased prevalence compared with results using conventional methods (1, 3, 4, 5). Vu et al. (3) suggested that as many as 46% of culture-negative diarrheal stool samples were positive for Shigella by quantitative PCR (qPCR). When qPCR is used where Shigella is most prevalent, it, like culture, requires mechanical and technical expertise to produce accurate estimates. In this study, we aim to compare the diagnostic accuracy of traditional culture-based techniques versus qPCR for the detection of Shigella.

Quantitative culture methods demonstrated that volunteers with diarrhea tend to have higher quantities of bacteria isolated from their stool than do those without diarrhea (6, 7, 8). Similarly, other studies have used qPCR to investigate the causes of the intestinal disease associated with norovirus and Escherichia coli (9, 10). In determining the cause of diarrheal illness, qPCR might prove to be a useful tool where pathogen load might be strongly associated with the ability to cause disease. If a new test is able to detect the presence of Shigella in stools in a greater proportion than traditional microbiological techniques, we must assess whether the test is able to distinguish between those with and without illness, which gives clinical relevance to the new diagnostic test. We must also assess whether higher sensitivity comes at the cost of a substantial decrease in specificity (11, 12). Finally, if we find that a larger number of asymptomatic carriers of Shigella exist than was previously thought, this might provide vital clues about the natural history of and the risk factors associated with shigellosis, as well as generate information that is crucial for limiting the spread of the disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and participants.

Stool specimens were collected during the Global Enteric Multisite Study (GEMS), a case-control study of moderate-to-severe diarrhea (MSD) in children <5 years of age. Details of the GEMS are presented elsewhere (13). We studied a subset of samples for which 6 g of stool was available following collection. Cases with MSD were enrolled upon presentation to a health clinic. MSD eligibility criteria included dehydration (sunken eyes, loss of normal skin turgor, or a decision to initiate intravenous hydration), presence of blood in the stool (dysentery), or a decision to hospitalize the child. Cases with blood in the stool were identified using a broad definition of positive that included blood in the stool reported by either the primary caretaker or a technician in the laboratory. Controls were sought following case enrollment and were sampled from a demographic surveillance database of the area; they were included if they reported no diarrhea within the previous 7 days. Individuals were excluded if they were unable to produce 6 g of stool or they were unable or unwilling to consent to involvement in the study. All specimens were collected between March 2008 and June 2009. One specimen was collected from each child at the time of enrollment. The institutional review boards at all participating institutions reviewed and approved the study protocol.

Microbiology methods.

Stool specimens were handled following the GEMS protocol (14). The specimens were collected in sterile containers, kept at 2 to 8°C while in transit, and examined within 24 h (<6 h between evacuation and placement into transport medium, which was made weekly, and <18 h before the transport swab inoculated the culture plates). Shorter testing times are associated with case specimens, since they were collected from the child while in the clinic, while control specimens were collected by a messenger from the child at home. Each fresh stool specimen was aliquoted into multiple tubes, some of which were frozen at −80°C. An aliquot was placed in Cary-Blair transport medium and another in buffered glycerol saline. A swab from the Cary-Blair medium and one from the buffered glycerol saline were applied separately to both MacConkey and xylose lactose desoxycholate plates. The four plates (2 MacConkey and 2 xylose lactose desoxycholate) were incubated aerobically at 35 to 37°C for 24 to 48 h. Following incubation, no more than 10 isolated non-lactose-fermenting colonies and at least one representative colony of each suspicious morphotype from each plate were then inoculated into each of the following: triple sugar iron agar, motility indole ornithine medium, lysine decarboxylase agar, citrate and urea medium; then they were incubated overnight. If biochemical tests suggested Shigella spp. were present, colonies were typed by using pure colonies by direct slide agglutination with the appropriate antiserum (Denka Seiken or Reagensia). Positive cultures were sent to the CDC in Atlanta, GA, for serotype confirmation. If the colonies were not suggestive of Shigella spp. at 48 h, the specimen was considered culture negative.

To verify the true detection limits of the assay, 200 mg Shigella-negative stool (collected in North America) was mixed with either 107 or 105 CFU prior to DNA isolation. These two DNA samples were serially diluted 1:5 five times and were quantified by qPCR.

DNA was isolated from frozen stool samples by using a bead beater with 3-mm-diameter solid-glass beads (Sigma-Aldrich), and subsequently with 0.1-mm zirconium beads (BioSpec, Inc.), to disrupt the cells. The cell slurry was then centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 1 min, and the supernatant was processed using the Qiagen QIAamp DNA stool extraction kit. Extracted DNA was ethanol precipitated and shipped to the United States.

Quantitative PCR.

qPCR was conducted on three sets of specimens, the first of which contained 877 DNAs, the second of which contained 2,656 DNAs, and the third of which contained a North American stool sample with known quantities of Shigella; it was performed by a single lab technician who was blinded to the case, control, and culture status of the stool samples. Each DNA was tested by qPCR using the Applied Biosystems 7500/7500 Fast real-time PCR system with software v2.0.5 and SYBR green-based fluorescent dye. Primers for ipaH initiated the assay, which contained 10 to 1,717 ng of DNA, 8.5 μl of water, 1.5 μl each of 5 μM forward and reverse primers, and 12.5 μl of SYBR green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems) (3). The PCR was carried out for 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 95°C for 15 s, and 60°C for 1 min (2, 3). The gene copies in the specimens were determined by absolute quantification using a standard curve fitted for each 96-well plate. The standard curve was constructed with the total genomic DNA isolated by Qiagen columns, according to the manufacturer's instructions from Shigella flexneri 2b strain ATCC 12022. The standard curves for the first 11 plates are plotted in Fig. 1A. The R2 values of a linear model fit to the standard curves of cycle threshold (CT) versus log dilution of DNA in the standard ranged from 1.00 to 0.984 across all 42 plates. To convert the quantity given by the qPCR output to an estimate of the number of target gene copies, we computed that 1 ng of genomic DNA isolated from broth-grown S. flexneri 2b ATCC 12022 is approximately equal to 2 × 105 gene copies of ipaH, assuming a single copy of ipaH per genome. We used the concentration of DNA, determined spectrophotometrically (NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer, Thermo Scientific), in the sample and the quantitative PCR measurement to estimate the number of gene copies based on 100 ng of total stool DNA.

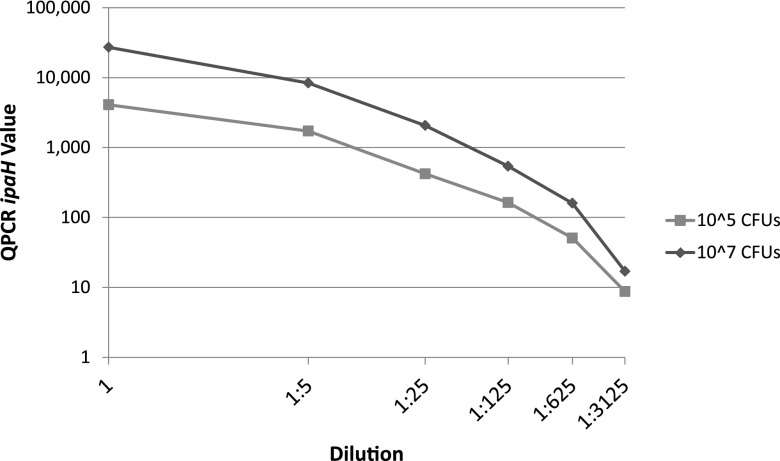

Fig 1.

(A) Standard curves for set 1 (n = 877). For each plate, a standard curve was constructed by plotting the cycle threshold (CT) values on the y axis and the known log-dilution of DNA of 1.0 to 0.00032 ng per ml in 5-fold dilutions on the x axis. (B) Decile graph for set 1 (n = 877). The quantities of ipaH gene copies were split into deciles with 88 or 87 samples per decile. The proportion of cases, samples positive for Shigella by culture, and samples positive for blood were plotted for each decile.

Genome sequencing.

Genome sequencing and analysis were performed on selected Shigella isolates using the methods and software described previously (15, 16). Identification of specific genes was completed with a comparison with BLAST to the assembled contigs.

Statistical analysis.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS v9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We calculated the sensitivity and specificity of (i) qPCR to MSD status, (ii) qPCR to culture status, and (iii) culture to MSD status. Sensitivity and specificity were calculated by comparing the results of the reference (culture or MSD diagnosis) to qPCR or culture. Sensitivity was calculated as the number of true positives (positive by both measures) divided by the number of reference positives. Specificity was calculated as the number of true negatives (negative by both measures) divided by the number of reference negatives. We constructed receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves from the continuous measurement of the number of gene copies per sample by plotting the estimated sensitivity by 1 − specificity. For ROC analysis in the model, we included gene copies as the independent variable and either case status or Shigella-culture positive as the outcome and dependent variable.

RESULTS

We selected 877 specimens from four GEMS sites: the Gambia, Mali, Kenya, and Bangladesh. Four hundred fourteen specimens were from patients with MSD, 463 from children without diarrhea (i.e., controls, all of whom were reported not to have had diarrhea in the past 7 days); 90 (74 from MSD patients, 16 from controls) samples were positive by the standard culture procedure for Shigella spp. qPCR was conducted on all 877 samples and CT values ranged from 4.06 to 39.20, with a mean value of 25.92. Comparing the results against those generated from the standard curve with known quantities of Shigella genomic DNA, the calculated target abundance ranged from 0 to 1 × 1010 gene copies of ipaH per 100 ng of stool DNA. Seven hundred ninety-nine samples had a target abundance calculated by qPCR that was >1.0. Of these, 89 were positive by standard culture. Target abundance was converted into output deciles, with 87 or 88 samples per decile. The range for each decile is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics: a description of demographic and clinical characteristics of children <5 years of age from two sets of samples included in the study

| Sample characteristic | Set 1 (n = 877) | Set 2 (n = 2,656) | Total (n = 3,533)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSDb (n [%]) | 414 (47.2) | 1,047 (39.7) | 1,461 (42) |

| Age (mean [SD]) (mo) | 17.6 (11.5) | 17.8 (12.4) | 17.8 (12.2) |

| Age group (n [%]) | |||

| 0 to <12 mo | 337 (38.4) | 1,032 (39.1) | 1,369 (38.9) |

| 12 to <24 mo | 326 (37.2) | 880 (33.4) | 1,206 (34.3) |

| 24 to 59 mo | 214 (24.4) | 725 (27.5) | 939 (26.7) |

| Male (n [%]) | 506 (57.7) | 1,460 (55.4) | 1,966 (55.9) |

| Site (n [%]) | |||

| Gambia | 348 (39.7) | 563 (21.4) | 911 (25.9) |

| Mali | 130 (14.8) | 112 (4.2) | 242 (6.9) |

| Kenya | 170 (19.4) | 1,385 (52.5) | 1,555 (44.3) |

| Bangladesh | 229 (26.1) | 577 (21.9) | 806 (22.9) |

| Antibiotic use (n [%]) | 12 (1.4) | 28 (1.1)c | 40 (1.1)c |

| Shigella-positive by culture (n [%]) | 90 (10.2) | 134 (5.1) | 224 (6.4) |

| Shigella quantity of <1.0 (n [%]) | 78 (9.0) | 483 (18.2) | 561 (15.8) |

| Shigella quantity decile (range [n]) | |||

| 1 | 0 to <1.30 (87) | 0 (483) | 0 (561) |

| 2 | 1.30 to <4.96 (88) | 1.0 to <3.60 (48) | 1.0 to <2.15 (145) |

| 3 | 4.96 to <12.76 (88) | 3.60 to <6.75 (266) | 2.15 to <8.18 (354) |

| 4 | 12.76 to <32.23 (88) | 6.75 to <22.71 (265) | 8.18 to <25.06 (353) |

| 5 | 32.23 to <71.49 (87) | 22.71 to <54.42 (266) | 25.06 to <59.19 (353) |

| 6 | 71.49 to <176 (88) | 54.42 to <128 (266) | 59.19 to <136 (354) |

| 7 | 176 to <593 (88) | 128 to <334 (265) | 136 to <381 (353) |

| 8 | 593 to <10,935 (88) | 334 to <1,503 (266) | 381 to <1,953 (354) |

| 9 | 10,935 to <525,416 (88) | 1,503 to <22,049 (266) | 1,953 to <55,261 (353) |

| 10 | >525,416 (87) | >22,049 (265) | >55,261 (353) |

| Maximum copy number | 1 × 1010 | 7.6 × 1010 | 7.6 × 1010 |

Some missing data account for the discrepancies in the data totals.

MSD, moderate-to-severe diarrhea.

Nineteen missing values.

We assessed the performance characteristics of our qPCR assay in detecting Shigella as a cause of MSD. We compared the proportion of MSD cases, the proportion of specimens that were positive for Shigella spp. by culture, and the proportion of specimens reporting dysentery, within each decile (Fig. 1B). The proportion of specimens in the first decile derived from MSD cases was 38%. This proportion remained at ≤55% in each decile until the ninth decile, where it increased to 70%. The highest proportion of cases, 78%, was found in the tenth decile. As the quantities of ipaH increased, the proportion of dysenteric stools also increased: 48%, or 42 specimens, of those in the highest decile were positive for visible blood in the stool. The proportions of positive cases, culture-positive stools, and dysentery-positive stools by each decile each had a significant (P < 0.0001) Cochran-Armitage test for trend.

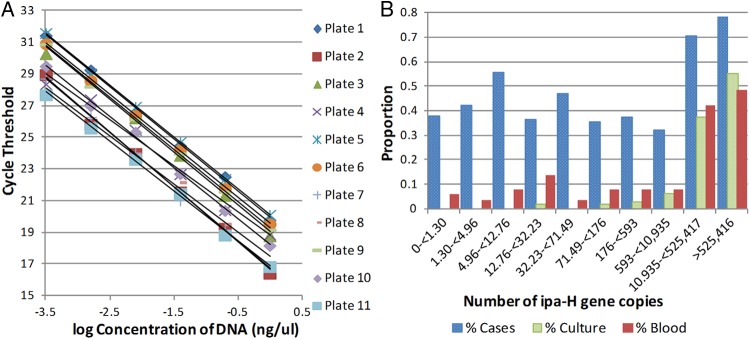

ROC curve analysis.

ROC curves were constructed from the sensitivity and 1-specificity of the number of gene copies determined by qPCR and either case status (Fig. 2A) or Shigella-culture positivity (Fig. 2B) as the test reference group. The area under the curve (AUC) was higher for predicting Shigella-culture positivity (0.9357) than for predicting case status (0.5901). The optimal cutpoint determined by the maximum Youden index (J = [sensitivity + specificity − 1]) for predicting both case status and Shigella-culture detection was approximately 2.9 × 104 ipaH copies per 100 ng of stool DNA; this correctly predicted 125 true-positive cases of MSD and 428 true-negative controls (17). One hundred fifty-eight samples (18%) were positive by this cutoff. One hundred twenty-five (79%) of 158 samples with ≥2.9 × 104 ipaH copies were cases of MSD. Within the 33 control samples, all four sites and a wide distribution of ages were represented. Importantly, 13 of the 33 control samples with qPCR values >2.9 × 104 ipaH copies were positive for Shigella using culture-based detection. Whole-genome sequencing of these 13 Shigella isolates revealed them to be typical isolates (4 S. flexneri, 3 S. boydii, and 6 S. sonnei). Additional characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Fig 2.

(A) ROC curve for model case-control status versus qPCR ipaH gene quantities from set 1 (n = 877) (B) ROC curve for model Shigella culture status versus qPCR ipaH gene quantities from set 1 (n = 877). Curves were plotted by calculating the sensitivity and 1-specificity of qPCR compared to case-control status (panel A) or Shigella culture status (panel B) at each unit increment in qPCR ipaH gene quantity. Squares indicate the points on the curve cutpoint of approximately 29,000 ipaH copies. The diamond in panel A indicates the values for sensitivity and 1 − specificity for culture.

Table 2.

Characteristics of control samples with high Shigella quantities

| Sample characteristic | Set 1 (n = 33) controls >2.9 × 104 ipaH copies | Set 2 (n = 100) controls >1.4 × 104 ipaH copies | Total (n = 143) controls >1.4 × 104 ipaH copies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site (n [%]) | |||

| The Gambia | 17 (51) | 24 (24) | 46 (32) |

| Mali | 2 (6) | 5 (5) | 12 (8) |

| Kenya | 5 (15) | 34 (34) | 39 (27) |

| Bangladesh | 9 (27) | 37 (37) | 46 (32) |

| Age (mean [SD]) (mo) | 18.8 (12.7) | 19.24 (12.9) | 19.25 (12.46) |

| Age group | |||

| 0 to <12 mo | 10 (30) | 37 (37) | 49 (34) |

| 12 to <24 mo | 14 (42) | 32 (32) | 53 (37) |

| 24 to 59 mo | 9 (28) | 31 (31) | 41 (29) |

We compared the sensitivities and specificities of Shigella qPCR and culture detection using MSD or no MSD as the reference standard (Table 3). Culture yielded a sensitivity of 17.9%, a specificity of 96.5%, and an odds ratio association with disease of 6.4 (95% confidence interval [CI], 3.6 to 11.5; P value < 0.0001). qPCR with ≥2.9 × 104 ipaH copies provided a sensitivity of 30.2% and a specificity of 92.8%. Children in our case-control sample population with qPCR with ≥2.9 × 104 ipaH copies had 5.6-times-higher odds of having diarrhea than did those with qPCR with <2.9 × 104 ipaH copies (95% CI, 3.7 to 8.5; P value < 0.0001). While the odds ratios for culture and qPCR with ≥2.9 × 104 ipaH copies are statistically indistinguishable, there were a total of only 90 stool samples that were positive for Shigella by culture, while there were 158 positive for Shigella using qPCR with ≥2.9 × 104 ipaH copies.

Table 3.

Comparison of sensitivity and specificity of culture and qPCRa

| Set and method | No. of MSD cases/no. of all Shigella positive cases | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Set 1 (n = 877) | |||||

| Shigella culture | 74/89 | 17.87 (14.30–21.91) | 96.75 (94.45–98.01) | 6.47 (3.65–11.47) | 4.05 × 10−13 |

| qPCR with 2.9 × 104 ipaH copies | 125/158 | 30.19 (25.81–34.87) | 92.84 (90.14–95.04) | 5.61 (3.72–8.46) | 2.69 × 10−19 |

| Set 2 (n = 2,656) | |||||

| Shigella culture | 98/133 | 9.40 (7.69–11.33) | 97.79 (96.94–98.46) | 4.59 (3.09–6.81) | 4.09 × 10−16 |

| qPCR with 1.4 × 104 ipaH copies | 201/300 | 19.27 (16.92–21.80) | 93.75 (92.45–94.89) | 3.58 (2.78–4.62 | 3.52 × 10−24 |

| Matched set (n = 2,874) | |||||

| Shigella culture | 129/172 | 10.70 (9.01–12.58) | 97.42 (96.54–98.13) | 5.41 (3.61–8.10) | <0.0001 |

| qPCR with 1.4 × 104 ipaH copies | 262/377 | 21.72 (19.43–24.16) | 93.11 (91.78–94.27) | 4.72 (3.57–6.23) | <0.0001 |

| All samples (n = 3,533) | |||||

| Shigella culture | 172/222 | 11.81 (10.19–13.57) | 97.55 (96.79–98.18) | 5.34 (3.87–7.37) | 3.80 × 10−29 |

| qPCR with 1.4 × 104 ipaH copies | 327/469 | 22.44 (20.32–24.67) | 93.06 (91.87–94.12) | 3.88 (3.14–4.79) | 7.28 × 10−40 |

Shown are the number of cases identified as positive by culture or qPCR with a threshold of 2.9 × 104 ipaH gene copies for set 1 and 1.4 × 104 for set 2, matched set, and all samples. Sensitivities and specificities were calculated using MSD disease status as the reference.

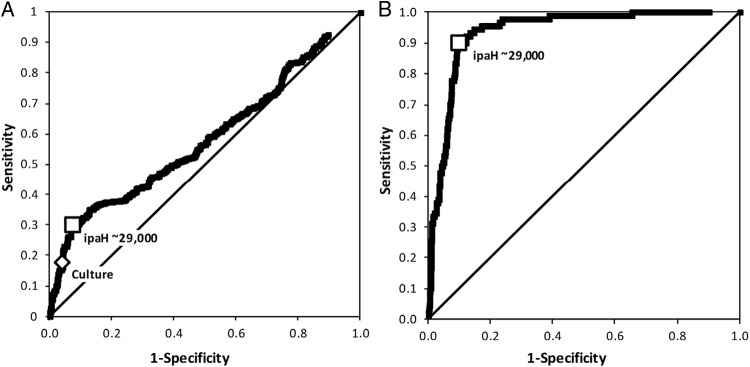

Validation of assay using spiked stools.

In order to test the efficiency of our qPCR test, 200 mg of stool was mixed with 107 CFU and another 200 mg with 105 CFU of Shigella. Each DNA sample was serially diluted 1:5 five times. The results are shown in Fig. 3. The linear dilution reveals a constant number of copies of ipaH. Averaged over the five measurements, the 200 mg of stool with 105 Shigella CFU measured by qPCR yielded 3,740 ipaH copies, while the sample with 107 CFU yielded 19,600 ipaH copies. Based on these values, one copy of ipaH by our qPCR measurement represents approximately 4 to 188 CFU per 200 mg of stool.

Fig 3.

qPCR results from spiked experiment. Two stool samples of 200 mg were each spiked with 107 or 105 CFU of Shigella flexneri. After DNA isolation, the samples were diluted and amplified using the primers for ipaH.

Validation using a second epidemiologic sample.

We performed qPCR on another group of specimens from the GEMS, which were generated using identical clinical and microbiological protocols but were collected at later time points than the first set. This analysis included a total of 2,656 samples, comprising 1,047 (40%) MSD cases and 1,609 (60%) controls without diarrhea in the previous 7 days and with a similar age and site distribution as in the initial analysis (Table 1). Results of the second qPCR set revealed that 82% of the samples were positive for Shigella with a range of ipaH copies from 1 to 7.6 × 1010. Analysis of ROC curves constructed from this data set indicated a quantitative cutpoint of approximately 1.4 × 104 ipaH copies as being optimal for the detection of MSD caused by Shigella. The odds ratio between Shigella status and MSD at this cutpoint was 3.58 (95% CI, 2.78 to 4.62), and using MSD status as our reference test, a sensitivity of 19% and specificity of 95% were calculated in this second set (Table 3). The odds ratio for culture positivity and MSD in this second sample was 4.59 (95% CI, 3.09 to 6.81). One hundred control samples had high levels of ipaH, 21 of which were culture positive. Among the 134 culture-positive samples, 42 (31%) produced qPCR values below, while 92 (69%) were above, the cutpoint.

In our GEMS MSD subset, conventional bacteriologic culture detected Shigella in 6.3% (224 of 3,533) of stool samples. In contrast, qPCR detects Shigella at a level of ≥1 copy per 100 ng of stool DNA in 84.2% (2,972 of 3,533) of all samples. Among children with MSD, 89% (1,307 of 1,461) had detectable ipaH genes. Thus, applying the cutpoint of qPCR with ≥1.4 × 104 ipaH copies is critical for the diagnosis of MSD that is attributed to Shigella. Using this cutpoint, 327 cases and 142 controls yielded high levels of ipaH target. Among the 172 Shigella culture-positive samples, 48 (28%) were below and 124 (72%) were above the cutpoint. The asymptomatic carriage rate of Shigella qPCR with ≥1.4 × 104 ipaH copies, which was 6.9% (142 of 2,072), is similar to the asymptomatic carriage rate of 2.4% (n = 52) that was detected by culture. Among the 3,533 children, culture revealed that 12% of MSD could be attributed to Shigella; in contrast, qPCR with ≥1.4 × 104 ipaH copies yielded a distinctly larger proportion, as 22% of MSD cases could be attributed to Shigella infection.

Within the larger GEMS sample, 2,874 samples were derived from cases and controls that were matched at the time of enrollment for age, site, and time of enrollment; these included 1,206 cases and 1,668 controls. A conditional logistic regression of the matched 2,874 individuals with Shigella culture status in cases to controls resulted in an odds ratio of 5.41 (3.61 to 8.10), while using a cutpoint of 1.4 × 104 ipaH copies resulted in an odds ratio of 4.72 (95% CI, 3.57 to 6.23). The attributable fraction can be calculated by culture to be 0.0962 (116 Shigella cases), or by qPCR with ≥1.4 × 104 ipaH copies to be 0.1768 (213 Shigella cases).

DISCUSSION

Our study evaluates the use of Shigella qPCR as a diagnostic method. We found that of the 1,461 stool samples from children with MSD and 2,072 stool samples from control children, 84% of samples were positive for ≥1 Shigella ipaH target copy per 100 ng of stool DNA. ROC analysis revealed that approximately 1.4 × 104 ipaH copies per 100 ng of stool DNA was the cutoff value, producing the best performance in terms of sensitivity and specificity. This cutoff identified 469 stools as having high levels of Shigella, of which 327 (70%) were stools from children with MSD. We retained the original GEMS matching of 1,206 cases and 1,668 controls on age, site, gender, residence, and time. A conditional logistic regression of these matched samples with a cutpoint of 1.4 × 104 ipaH copies resulted in an odds ratio comparing Shigella in cases to controls of 4.72 (95% CI, 3.57 to 6.23). A conditional logistic regression comparing Shigella-culture status in these cases and controls resulted in an odds ratio of 5.41 (3.61 to 8.10). While these two odds ratios are statistically indistinguishable, culture clearly identified fewer cases of MSD as having Shigella than did qPCR. The attributable fraction of MSD due to Shigella based on culture was therefore only 54% of that estimated by the qPCR method, suggesting that in this population, Shigella might be twice as commonly associated with MSD as was appreciated previously (18).

Among children who were culture positive and had a qPCR result of ≥1.4 × 104 ipaH copies, some had diarrhea and some did not. Possible explanations for this observation include genetic differences among the isolates of Shigella, protective polymorphic alleles in some children, differences in the gut microbiota that enhance or decrease a child's probability of disease, or an immune response based on prior exposure of either the mother (via breast milk or transplacentally acquired antibody) or child (19).

We propose that a quantitative test of Shigella genomes within a stool sample might be a more suitable method of diagnosis than is culture-based identification. qPCR identified nearly twice as many Shigella-positive children with MSD as did culture. Compared to the presence or absence of MSD, qPCR had a greater number of Shigella-positive (or true-positive) MSD cases and fewer Shigella-negative or (false-negative) MSD cases. Culture had fewer Shigella-positive controls and a greater number of Shigella-negative controls. Assuming that individuals who are without disease will not seek medical attention, the number of false positives is clinically less relevant than is the number of true positives. Previous research has shown that PCR-diagnosed infections are clinically similar to culture-proven shigellosis, and a test that accurately predicts when the presence of Shigella is associated with disease will be beneficial (20). Shigella counts of >1.4 × 104 ipaH copies were significantly associated with MSD without a considerable decrease in specificity; on the other hand, culture methods sacrifice the limit of detection for specificity.

This study has several limitations. First, we have used the ipaH gene as a surrogate marker for Shigella detection. Our gene target, ipaH, is also found in enteroinvasive E. coli, and the methods of this study do not distinguish between these similar pathogens. Nevertheless, it is generally thought that Shigella is much more prevalent and thus is likely to represent most of the ipaH-associated organisms that were detected. In addition, the ipaH gene is often found in multiple copies in the genome. Although our PCR primers are designed to detect only one ipaH copy, unless the organism is isolated, it is difficult, at best, to identify how many ipaH copies are present in a particular genome; this might impact our interpretation of one ipaH copy to one Shigella bacterium in our conversion of quantity given by the qPCR output to the estimated number of target gene copies. Our quantification of Shigella compares the amplification of a standard dilution of Shigella DNA in water compared to test DNAs isolated from stool that might have inhibitors present that will reduce the efficiency of the PCR. Our spike experiments revealed that 1 copy of ipaH by qPCR represents 4 to 188 CFU per 200 mg of stool. While the spiked stool certainly accounts for some variation in DNA isolation and the role of inhibitors, there are likely various amounts of inhibitors and DNA concentrations present across our samples; therefore, amounts should be interpreted as estimates rather than as fully accurate and precise measurements. Finally, the time between when the stool was passed and culture was performed was slightly shorter in case samples than in controls; however, further analysis revealed that the time between stool evacuation and testing was not negatively correlated with culture positivity, and therefore, this time difference did not bias culture methods to detect Shigella in cases.

The strengths of our study include testing a quantitative method to assess the amount of Shigella DNA present in a stool sample. As opposed to the binary presence-or-absence nature of Shigella culture, qPCR gives us an approximation of the pathogen load within a sample and also gives us the ability to create a clinically relevant cutpoint from our data. When we see stools with Shigella, indicated by either qPCR or culture techniques, quantification becomes an important tool to assess the association of the pathogen with clinical symptoms. Our sample did not select for MSD cases that were likely to be caused by Shigella. This can explain why the area under the ROC curve and the sensitivity for Shigella quantity compared to disease status are relatively low. We did not exclude cases of disease that had other pathogens present in the sample and thus might have been caused by those rather than by Shigella.

In addition to informing quantitative detection techniques, the natural history and risk factors associated with diarrheal disease caused by Shigella are shifted by our qPCR data. Assuming that the Shigella DNA in stools from persons without diarrhea represents viable infectious organisms (consistent with our whole-genome sequencing data), our data suggest that the prevalence of asymptomatic excretors of Shigella is higher than has been appreciated. Further studies are required to examine the epidemiological importance of such individuals. The attributable fraction of MSD caused by Shigella as estimated by culture is substantially less than the attributable fraction estimated with a qPCR result of ≥1.4 × 104 ipaH copies, consistent with a suggestion that Shigella might be more common than was previously thought. We suggest that future studies of Shigella epidemiology employ qPCR to ascertain most accurately the burden of infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

We declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 27 March 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. von Seidlein L, Kim DR, Ali M, Lee H, Wang X, Thiem VD, Canh do G, Chaicumpa W, Agtini MD, Hossain A, Bhutta ZA, Mason C, Sethabutr O, Talukder K, Nair GB, Deen JL, Kotloff K, Clemens J. 2006. A multicentre study of Shigella diarrhoea in six Asian countries: disease burden, clinical manifestations, and microbiology. PLoS Med. 3:e353 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0030353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Taniuchi M, Walters CC, Gratz J, Maro A, Kumburu H, Serichantalergs O, Sethabutr O, Bodhidatta L, Kibiki G, Toney DM, Berkeley L, Nataro JP, Houpt ER. 2012. Development of a multiplex polymerase chain reaction assay for diarrheagenic Escherichia coli and Shigella spp. and its evaluation on colonies, culture broths, and stool. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 73:121–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vu DT, Sethabutr O, Von Seidlein L, Tran VT, Do GC, Bui TC, Le HT, Lee H, Houng HS, Hale TL, Clemens JD, Mason C, Dang DT. 2004. Detection of Shigella by a PCR assay targeting the ipaH gene suggests increased prevalence of shigellosis in Nha Trang, Vietnam. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:2031–2035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Samosornsuk S, Chaicumpa W, von Seidlein L, Clemens JD, Sethabutr O. 2007. Using real-time PCR to detect shigellosis: ipaH detection in Kaeng-Khoi District, Saraburi Province, Thailand. Thammasat Int. J. Sci. Technol. 12:52–57 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Phantouamath B, Sithivong N, Insisiengmay S, Ichinose Y, Higa N, Song T, Iwanaga M. 2005. Pathogenicity of Shigella in healthy carriers: a study in Vientiane, Lao People's Democratic Republic. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 58:232–234 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Losonsky GA, Wasserman SS, Hale TL, Taylor DN, Sadoff JC, Levine MM. 1995. A modified Shigella volunteer challenge model in which the inoculum is administered with bicarbonate buffer: clinical experience and implications for Shigella infectivity. Vaccine 13:1488–1494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tacket CO, Kotloff KL, Losonsky G, Nataro JP, Michalski J, Kaper JB, Edelman R, Levine MM. 1997. Volunteer studies investigating the safety and efficacy of live oral El Tor Vibrio cholerae O1 vaccine strain CVD 111. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 56:533–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Taylor DN, Tacket CO, Losonsky G, Castro O, Gutierrrez J, Meza R, Nataro JP, Kaper JB, Wasserman SS, Edelman R, Levine MM, Cryz SJ. 1997. Evaluation of a bivalent (CVD 103-HgR/CVD 111) live oral cholera vaccine in adult volunteers from the United States and Peru. Infect. Immun. 65:3852–3856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Phillips G, Lopman B, Tam CC, Iturriza-Gomara M, Brown D, Gray J. 2009. Diagnosing norovirus-associated infectious intestinal disease using viral load. BMC Infect. Dis. 9:1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barletta F, Ochoa TJ, Mercado E, Ruiz J, Ecker L, Lopez G, Mispireta M, Gil AI, Lanata CF, Cleary TG. 2011. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction for enteropathogenic Escherichia coli: a tool for investigation of asymptomatic versus symptomatic infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 53:1223–1229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Giocoli G, Biesheuvel CJ, Gidding HF, Andresen D. 2009. Advances in diagnostics for microbial agents: can clinical validation keep pace with the technical promises? Ann. Ist. Super. Sanità 45:168–172 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hadgu A, Dendukuri N, Hilden J. 2005. Evaluation of nucleic acid amplification tests in the absence of a perfect gold-standard test: a review of the statistical and epidemiologic issues. Epidemiology 16:604–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kotloff K, Blackwelder WC, Nasrin D, Nataro JP, Farag TH, van Eijk A, Adegbola RA, Alonso PL, Breiman RF, Faruque ASG, Saha D, Sow SO, Sur D, Zaidi AKM, Biswas K, Panchalingam S, Clemens JD, Cohen D, Glass RI, Mintz ED, Sommerfelt H, Levine MM. 2012. The Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS) of diarrheal disease in infants and young children in developing countries: epidemiologic and clinical methods of the case/control study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 55(Suppl 4):S232–S245 doi:10.1093/cid/cis753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Panchalingam S, Antonio M, Hossain A, Mandomando I, Ochieng B, Oundo J, Ramamurthy T, Tamboura B, Zaidi AK, Petri W, Houpt E, Murray P, Prado V, Vidal R, Steele D, Strockbine N, Sansonetti P, Glass RI, Robins-Browne RM, Tauschek M, Svennerholm A, Kotloff K, Levine MM, Nataro JP. 2012. Diagnostic microbiologic methods in the GEMS-1 case/control study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 55(Suppl 4):S294–S302 doi:10.1093/cid/cis754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rasko DA, Webster DR, Sahl JW, Bashir A, Boisen N, Scheutz F, Paxinos EE, Sebra R, Chin-Shan C, Iliopoulos D, Klammer A, Peluso P, Lee L, Kislyuk AO, Bullard J, Kasarskis A, Wang S, Eid J, Rank D, Redman JC, Steyert SR, Frimodt-Møller J, Struve C, Petersen AM, Krogfelt KA, Nataro JP, Schadt EE, Waldor MK. 2011. Origins of the E. coli strain causing an outbreak of hemolytic-uremic syndrome in Germany. N. Engl. J. Med. 365:709–717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sahl JW, Setinsland H, Redman JC, Angiuoli SV, Nataro JP, Sommerfelt H, Rasko DA. 2011. A comparative genomic analysis of diverse clonal types of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli reveals pathovar-specific conservation. Infect. Immun. 79:950–960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Akobeng A. 2007. Understanding diagnostic tests 3: receiver operating characteristic curves. Acta Paediatr. 96:644–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bruzzi P, Green SB, Byar DP, Brinton LA, Schairer C. 1985. Estimating the population attributable risk for multiple risk factors using case-control data. Am. J. Epidemiol. 122:904–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Levine MM, Robins-Browne RM. 2012. Factors that explain excretion of enteric pathogens by persons without diarrhea. Clin. Infect. Dis. 55(Suppl 4):S303–S311 doi:10.1093/cid/cis789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gaudio P, Sethabutr O, Echeverria P, Hoge CW. 1997. Utility of a polymerase chain reaction diagnostic system in a study of the epidemiology of shigellosis among dysentery patients, family contacts and well controls living in a shigellosis-endemic area. J. Infect. Dis. 176:1013–1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]