Abstract

We report the characteristics of 115 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli clinical isolates, from 115 unique Danish patients, over a 1-year study interval (1 October 2008 to 30 September 2009). Forty-four (38%) of the ESBL isolates represented sequence type 131 (ST13)1, from phylogenetic group B2. The remaining 71 isolates were from phylogenetic groups D (27%), A (22%), B1 (10%), and B2 (3%). Serogroup O25 ST131 isolates (n = 42; 95% of ST131) comprised 7 different K antigens, whereas two ST131 isolates were O16:K100:H5. Compared to non-ST131 isolates, ST131 isolates were associated positively with CTX-M-15 and negatively with CTX-M-1 and CTX-M-14. They also were associated positively with 11 virulence genes, including afa and dra (Dr family adhesins), the F10 papA allele (P fimbria variant), fimH (type 1 fimbriae), fyuA (yersiniabactin receptor), iha (adhesin siderophore), iutA (aerobactin receptor), kpsM II (group 2 capsules), malX (pathogenicity island marker), ompT (outer membrane protease), sat (secreted autotransporter toxin), and usp (uropathogenicity-specific protein) and negatively with hra (heat-resistant agglutinin) and iroN (salmochelin receptor). The consensus virulence gene profile (>90% prevalence) of the ST131 isolates included fimH, fyuA, malX, and usp (100% each), ompT and the F10 papA allele (95% each), and kpsM II and iutA (93% each). ST131 isolates were also positively associated with community acquisition, extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) status, and the O25, K100, and H4 antigens. Thus, among ESBL E. coli isolates in Copenhagen, ST131 was the most prevalent clonal group, was community associated, and exhibited distinctive and comparatively extensive virulence profiles, plus a greater variety of capsular antigens than reported previously.

INTRODUCTION

Escherichia coli is the most common agent of urinary tract infection (UTI) and Gram-negative bacteremia. E. coli sequence type 131 (ST131) is a recently emerged worldwide pandemic clonal group, causing widespread antimicrobial-resistant infections (1). Although many studies have examined various aspects of E. coli ST131 in diverse locales and clinical contexts (1, 2), little is known about ST131's O:K:H serotypes, especially in relation to community versus health care site of acquisition, coresistance phenotypes, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) variants, and pulse-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) types. Such data are needed to more fully understand the epidemiology of ST131 and to help guide diagnostic and preventive efforts.

CTX-M-type beta-lactamases have become the dominant ESBLs worldwide during the past decade (3). The responsible blaCTX-M genes are known to be associated with conjugative plasmids and certain successful bacterial clones, notably ST131 (4).

Here we assessed the prevalence of E. coli ST131 among 115 consecutive ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from 115 patients (2008-2009) from 3 hospitals and 100 general practitioners' offices in Copenhagen, Denmark. Subsequently, we compared ST131 and non-ST131 ESBL isolates for multiple host and bacterial characteristics, such as sex, age, specimen type, hospital versus community source, ESBL type, serotypes, virulence genes, and resistance profiles.

(These results were presented in part as a poster at the 22nd European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 2012.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical and epidemiological information.

To identify all available unique (by patient) ESBL E. coli isolates held by the Department of Clinical Microbiology, Hillerød Hospital, within the study period (1 October 2008 to 30 September 2009), the laboratory's microbiological database was searched for E. coli isolates, stratified by presumptive ESBL status. The Hillerød Hospital clinical laboratory provides laboratory services to 3 hospitals and 100 general practitioners' offices in Copenhagen, Denmark. Initial identification had been done using beta-glucoronidase agar plates (Statens Serum Institut) and Vitek 2. All E. coli isolates of clinical significance were routinely screened for ESBL production (as explained below). Presumed ESBL isolates are routinely saved. The project was approved by the local ethical committee.

For patients with multiple E. coli isolates, a single representative isolate was selected for analysis according to the first isolate found, with preference given to ESBL isolates (if any). From 5,473 total patients with ≥1 E. coli isolate, 5,473 single-patient putative E. coli isolates (81% from urine, 5% from blood, 14% from other sources) were selected, of which 129 had been identified as ESBL producers. Upon confirmatory testing, 11 isolates proved not to be E. coli, 2 were not ESBL producers, and 1 was subsequently lost. Thus, 115 isolates from 115 different patients infected with ESBL E. coli from 2008-2009 were studied.

Definitions.

E. coli isolates from clinical specimens that were collected for culture >2 days after a patient's admission to hospital, within 3 months after hospital discharge, or within 30 days of an outpatient dialysis session were considered hospital acquired or health care associated; all others were considered community acquired (5). The hospital administrative database was searched for the date(s) of admission(s), and the database of the department of clinical microbiology was searched for the collection date of the sample and which clinical department or general practitioner (GP) had requested the test.

Susceptibility testing.

The clinical laboratory routinely screens all E. coli isolates for ESBL production using cefpodoxime disk diffusion semiconfluent growth with Oxoid disks (Basingstoke, United Kingdom) on Isosensitest agar (SSI Diagnostica, Hillerød, Denmark). Strains with a zone diameter for cefpodoxime of ≤24 mm undergo phenotypic confirmatory testing for ESBL production using the double-disk method with ceftazidime and cefotaxime tablets, with or without clavulanate (Neo-Sensitabs; Rosco, Tåstrup, Denmark). Isolates exhibiting a >-5-mm zone difference between the single and combination tablets for any of these antibiotics are considered ESBL producers. MICs to 18 antibiotics, including amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, ampicillin, apramycin, cefotaxime, ceftiofur, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, colistin, florfenicol, gentamicin, meropenem, nalidixic acid, neomycin, spectinomycin, streptomycin, sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, and trimethoprim, are routinely determined by broth microdilution using the Sensititre system (Trek Diagnostic Systems Ltd., United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer's instructions and CLSI guidelines. Results are interpreted according to European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) guidelines (http://www.eucast.org). E. coli ATCC 25922 is used as an internal control.

Phenotypic characteristics.

The selected isolates were subcultured from frozen stocks and were reidentified using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization–time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry (Bruker Daltonics), calibrated with the Bruker E. coli bacterial test standard for mass spectrometry. Serotyping was done according to the method of Ørskov and Ørskov (6). The K antigen was determined by countercurrent immunoelectrophoresis involving K-specific antisera, except for the K1 and K5 antigens, which were detected using K1- and K5-specific phages. Verocytotoxin was detected by using the Verocell assay (7). Alpha- and enterohemolysin production was detected on blood agar plates after 24 h of incubation (8). Biofilm production was assessed by using an assay in which overnight cultures of bacteria were diluted 1:50 in Luria-Bertani broth or M9 minimal medium supplemented with 0.5% glucose and incubated in 96-well polystyrene microtiter plates (Nunc) for 24 h. After washing three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), staining with 0.5% crystal violet for 5 min, and washing once with PBS, biofilm formation was quantified by dissolving the crystal violet and measuring the optical density at 595 nm.

ESBL enzymes.

The presence of β-lactamase genes was investigated by PCR and nucleotide sequencing with primers specific for blaTEM, blaCTX-M, blaOXA-2, blaOXA-10, and blaSHV (9).

Phylogenetic analysis and detection of ST131.

Isolates were assigned to major E. coli phylogenetic groups (A, B1, B2, and D) by using a triplex PCR-based method (10). ST131 status was determined using real-time PCR (11) and conventional PCR (12). Isolates positive by both methods were considered confirmed ST131 isolates, whereas those positive by only one method were considered possible ST131 isolates and underwent confirmatory multilocus sequence typing (MLST), as described below. Clonal group A (CGA) was screened for using a specific PCR, with selective MLST confirmation (13). Multilocus sequence typing was performed according to the Achtman scheme using seven housekeeping genes, i.e., adk, fumC, gyrB, icd, mdh, purA, and recA. Procedures, primers, and sequence type (ST) assignment were as described at http://mlst.ucc.ie/mlst/dbs/Ecoli.

Virulence genotyping.

Isolates were tested for various extraintestinal and some diarrheagenic virulence genes by two different PCR methods, comprising a wide array of markers with minimal overlap. Testing was done in duplicate using independently prepared boiled lysates of each isolate, together with appropriate positive and negative controls. First, 35 virulence markers of extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) and the F10 papA allele (P fimbria structural subunit variant) were detected using established PCR-based assays (13–16). Isolates were regarded as ExPEC if positive for ≥2 of papA and/or papC (P fimbriae; counted as one), sfa and foc (S and F1C fimbriae), afa and dra (Dr-binding adhesins), kpsM II (group 2 capsule), and iutA (aerobactin system) (17). The combination “kpsM II positive, kii negative” was interpreted as indicative of the K2 capsule (18).

Second, a multiplex PCR developed by Boisen et al. (19) was used to screen for the diarrheagenic enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC)-associated putative virulence genes aggR, aatA, and aaiC. Strains exhibiting ≥1 of the aggR, aatA, and aaiC genes were considered EAEC (19).

O-type PCR.

Molecular confirmation of O types O25b and O16 was accomplished by PCR-based detection of the corresponding rfb variants (20, 21).

PFGE analysis.

ST131 isolates underwent PFGE analysis according to the PulseNet protocol (22). Pulsotypes were defined at the ≥94% profile similarity level in comparison with index isolates, which corresponds approximately with a ≤3-band difference, suggesting genetic relatedness (23).

Statistical methods.

Comparisons of proportions were tested using Fisher's exact test (2-tailed). Comparisons involving continuous variables were tested using the Mann-Whitney U test. Statistical significance was defined as a P value of <0.05.

RESULTS

Epidemiological and specimen type associations.

Among the hospital laboratory's 5,473 total single-patient E. coli isolates (81% from urine, 5% from blood, and 14% from other sources) during the 1-year study period in 2008-2009, 115 isolates (2%) were confirmed ESBL producers. Of these, the majority (97/115; 84%) were from urine, whereas 5 were from blood, 4 from wounds, 6 from feces, and 3 from respiratory specimens.

Phylogenetic group and MLST.

Of the 115 ESBL study isolates, 44 (38%) represented the ST131 clonal group, all from phylogenetic group B2. Forty-two isolates were identified as ST131 by both methods, whereas two others were so identified only by single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) PCR, which was confirmed by MLST. The remaining 71 isolates (62%) were from phylogenetic groups D (27% of total), A (22%), B1 (10%), and B2 (3%). Therefore, ST131 was by far the predominant clonal group among the ESBL isolates, accounting for nearly all group B2 ESBL isolates and a greater overall proportion of isolates than any other single phylogenetic group.

ST131 status versus demographics, specimen type, source, and site of acquisition.

Of the 115 source patients, 75 (65%) were females, and the median age was 69 years (range, <1 year to 98 years), without significant sex or age differences in relation to ST131 status. Specimen type also was not significantly associated with ST131 status (not shown). In contrast, 76 isolates (66%) presumably were community acquired, including 40/44 (91%) of ST131 isolates, versus 36/71 (51%) of non-ST131 isolates (P < 0.001). Thus, although ST131 status did not vary significantly in relation to host characteristics or specimen type, ST131 was significantly associated with community acquisition.

Serotypes.

According to O:K:H serotyping (Table 1), collectively the 44 ST131 isolates exhibited two O antigens (O25 [n = 33] and O16 [n = 2]), two flagellar antigens (H4 [n = 41] and H5 [n = 2]), and 7 K antigens (K100 [n = 24], K5 [n = 7], K2 and K16 [n = 2 each], and K20,23, K22, and K98 [n = 1 each]). All serogroup O25 ST131 isolates contained the O25b rfb variant. In contrast, the two O16 ST131 isolates, which also were the two “ST131-specific SNP-positive, pabB/O25b-negative” ST131 isolates, contained the O16 rfb variant. ST131 was significantly associated with the O25, K100, and H4 antigens (for each, P < 0.001). In contrast, the 71 non-ST131 isolates were considerably more diverse antigenically, exhibiting 31 O antigens, 28 K antigens, and 20 H antigens. Accordingly, only 15/44 (34%) of the ST131 isolates, versus 68/71 (95%) of the non-ST131 isolates, exhibited a unique O:K:H serotype (P < 0.001), and ST131 isolates and non-ST131 isolates did not overlap by O:K:H serotype. Prevalent ST131-associated O:K:H serotypes included O25:K100:H4 (n = 18) and O25:K5:H4 and O25:K− (no capsular antigen present):H4 (n = 5 each).

Table 1.

Serotypes of 115 ST131 and non-ST131 ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from Copenhagen (2008-2009)

| Serotypea | Prevalence [no. (%)] of serotype in ST group (nb) |

P valuec | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (115) | ST131 (44) | non-ST131 (71) | ||

| O25:K100:H4 | 18 (16) | 18 (41) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| O25:K−:H4 | 5 (4) | 5 (11) | 0 (0) | 0.01 |

| O25:K5:H4 | 4 (3) | 4 (9) | 0 (0) | 0.04 |

| Orough:K100:H4 | 4 (3) | 4 (9) | 0 (0) | 0.04 |

| O16:K100:H5 | 2 (2) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | |

| O25:K+:H4 | 2 (2) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | |

| Orough:K5:H4 | 2 (2) | 2 (5) | 0 (0) | |

| O1:K20,K23:H34 | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | |

| O8:K29:H9 | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | |

| O20:K−:H9 | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | |

| Others | 72d (63) | 7d (16) | 65 (92) | <0.001 |

All serotypes present in ≥2 isolates each are shown; those in the table in the supplemental material were present in only 1 isolate each.

n, no. of isolates.

P values (ST131 vs. non-ST131), by Fisher's exact test (2-tailed), are shown where P < 0.05.

Listed in the table in the supplemental material.

ESBL enzymes.

Of the 115 total ESBL isolates, 92% produced CTX-M enzymes (Table 2), most commonly CTX-M-15 (52%) but also CTX-M-14 (19%), CTX-M-1 (11%), and CTX-M-27 (5%). Additionally, one novel SHV ESBL variant was found, whereas in 3 isolates (all non-ST131), no known ESBL enzyme could be identified. Compared with non-ST131 isolates, ST131 isolates were associated positively with CTX-M-15 (P < 0.001) and negatively with CTX-M-1 (P = 0.002) and CTX-M-14 (P = 0.006).

Table 2.

ESBL-encoding genes among 115 ST131 and non-ST131 ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from Copenhagen (2008-2009)

| ESBL genotype | Prevalence [no. (%)] of ESBL genotype in ST group (na) |

P valueb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (115) | ST131 (44) | non-ST131 (71) | ||

| CTX-M-1 | 13 (11) | 0 (0) | 13 (18) | 0.0045 |

| CTX-M-2 | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| CTX-M-3 | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| CTX-M-8 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| CTX-M-9 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| CTX-M-14 | 22 (19) | 3 (7) | 19 (27) | 0.006 |

| CTX-M-15 | 60 (52) | 35 (80) | 25 (35) | <0.001 |

| CTX-M-27 | 6 (5) | 4 (9) | 2 (3) | |

| CTX-M-55 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| SHV-12 | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | |

| SHV-new | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| TEM-12 | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | |

| TEM-52 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| Nontypeable | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 3 (4) | |

n, no. of isolates.

P values (ST131 vs. non-ST131), by Fisher's exact test (2-tailed), are shown where P < 0.05.

Virulence genotyping.

Compared with non-ST131 isolates, ST131 isolates were associated positively with 11 virulence genes, including afa and dra (Dr family adhesins), the F10 papA allele (P fimbria variant), fimH (type 1 fimbriae), fyuA (yersiniabactin receptor), iha (adhesin-siderophore), iutA (aerobactin receptor), kpsM II (group 2 capsules), malX (pathogenicity island marker), ompT (outer membrane protease), sat (secreted autotransporter toxin), and usp (uropathogenic-specific protein), and negatively with hra (heat-resistant agglutinin) and iroN (salmochelin receptor) (Table 3). The consensus virulence gene profile (i.e., gene prevalence > 90%) of the ST131 isolates included fimH, fyuA, malX, and usp (100% prevalence); ompT and the F10 papA allele (95% prevalence); and kpsM II and iutA (93% prevalence). The median number of virulence characters was 13 for the ST131 isolates, versus 7 for the non-ST131 isolates (P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Characteristics of 115 ST131 and non-ST131 ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from Copenhagen (2008-2009)

| Traita,b,c | Prevalence [no. (%)] of trait in ST group (nd) |

P valuee | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (115) | ST131 (44) | Non-ST131 (71) | ||

| afa and dra | 38 (33) | 31 (70) | 7 (10) | <0.001 |

| F10 papA allele | 45 (39) | 42 (95) | 3 (4) | <0.001 |

| fimH | 108 (94) | 44 (100) | 64 (90) | 0.04 |

| fyuA | 92 (80) | 44 (100) | 48 (68) | <0.001 |

| hra | 31 (27) | 6 (14) | 25 (35) | 0.02 |

| iha | 53 (46) | 40 (91) | 13 (18) | <0.001 |

| iron | 15 (13) | 2 (4.5) | 13 (18) | 0.04 |

| iutA | 86 (75) | 41 (93) | 45 (63) | <0.001 |

| kpsM II | 67 (58) | 41 (93) | 26 (37) | <0.001 |

| malX | 59 (51) | 44 (100) | 15 (21) | <0.001 |

| ompT | 68 (59) | 42 (95) | 26 (37) | <0.001 |

| sat | 50 (43) | 40 (91) | 10 (14) | <0.001 |

| usp | 55 (48) | 44 (100) | 11 (15) | <0.001 |

All are ExPEC-associated traits unless stated otherwise.

Only traits that yielded P < 0.05 (ST131 vs. non-ST131) in at least one comparison are shown. Traits shown in the table: afa and dra (Dr family adhesins), F10 papA allele (P fimbria variant), fimH (type 1 fimbriae), fyuA (yersiniabactin receptor), hra (heat resistant agglutinin), iha (adhesin-siderophore), iroN (siderophore receptor), iutA (aerobactin receptor), kpsM II (group 2 capsule), malX (pathogenicity island marker), ompT (outer membrane protease T), sat (secreted autotransporter toxin), and usp (uropathogenic-specific protein).

Traits detected in ≥1 isolate each but not yielding a significant between-group difference (definition, associated E. coli EAEC pathotype; all isolates were ExPEC unless stated otherwise: aatA (ABC transporter, EAEC), aggR (master regulator, EAEC), astA (enteroaggregative heat-stable enterotoxin, EAST-1; ExPEC and EAEC), cvaC (microcin V, ExPEC), bmaE (M fimbriae), clpG (fimbrial adhesin CS31A), cnf1 (cytotoxic necrotizing factor), fliC (H7 flagellin), hlyD (hemolysin), hlyF (hemolysin F), ibeA (invasion of brain endothelium), ireA (siderophore receptor), iss (increased serum survival), pap (P fimbria operon, including papEG and papG alleles I, II, and III), papAH, papC (P fimbria operon), rfc (O4 lipopolysaccharide, sfa and focDE (S and F1C fimbriae), sfaS (S fimbriae), tsh (temperature-sensitive hemagglutinin), and vat (vacolating autotransporter). Traits screened for but not detected in any isolate (definition, associated pathotype): aaiC (type VI secretion system, EAEC), cdtB (cytolethal distending toxin), focG (F1C fimbriae), gafD (G fimbriae), sepA (autotransporter protease, EAEC), and traT (serum resistance associated).

n, no. of isolates.

P values (ST131 vs. non-ST131), by Fisher's exact test (2-tailed), are shown where P < 0.05.

Detection of capsular antigens: serotyping versus PCR.

All 26 isolates with the K100 capsular antigen exhibited kpsM II, but only 3 were also positive with the kii primers. Thus, 23 serologically K100 isolates were thought to have the K2 capsular antigen based on molecular typing criteria (18). Additional K-antigen results other than K100 among isolates that by PCR were presumptively classified as K2 included K−, K2, and K20,23 (4 isolates each) and K+, K20, K22, K95, and K98 (one isolate each).

PFGE.

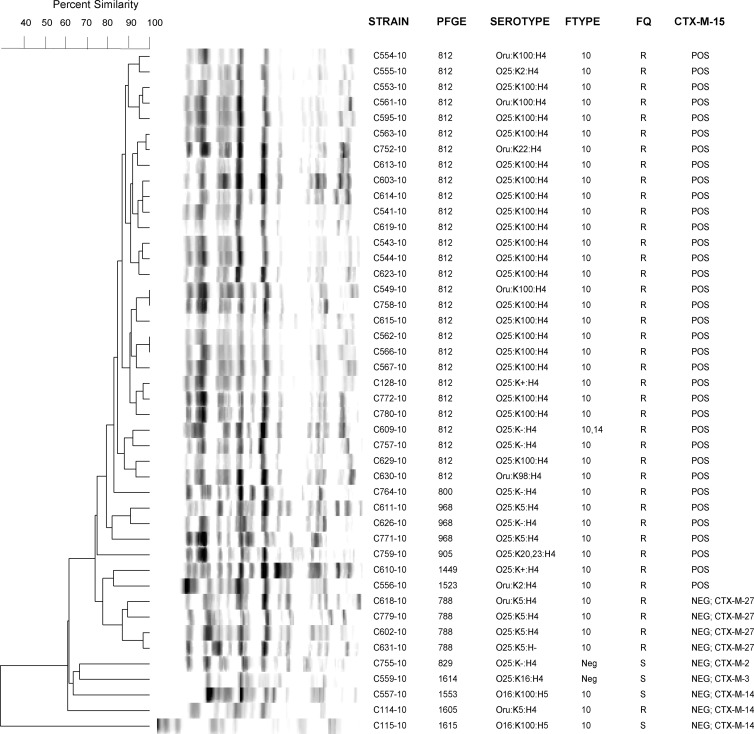

PFGE analysis of the 44 ST131 isolates (Fig. 1) showed considerable genetic similarity among the CTX-M-15-positive isolates, which were associated with the predominant pulsotypes 812 (n = 28; mostly K100) and 968 (n = 3; K5 or K−). The remaining ST131 isolates were grouped at the base of the tree and overall were more diverse than were the CTX-M-15-positive isolates. However, the 4 ST131 isolates that contained CTX-M-27 were grouped together as pulsotype 788, indicating clonality.

Fig 1.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) analysis of 44 extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing ST131 Escherichia coli isolates from Copenhagen (2008-2009). The dendrogram was inferred within the Bionumerics program according to the unweighted pair group method based on Dice similarity coefficients. Abbreviations: Ftype, P-fimbria antigen type; FQ, fluoroquinolone susceptibility (R, resistant; S, susceptible); CTX-M-15, ESBL enzyme.

Extraintestinal virulence-associated genes and EAEC.

Among the ESBL isolates, 41 (93%) of the ST131 isolates, versus only 29 (41%) of the non-ST131 isolates, fulfilled molecular criteria for ExPEC (P < 0.001). Two of the non-ST131 isolates that fulfilled criteria for ExPEC were also EAEC, versus no ST131 isolates (P > 0.05). Both EAEC isolates were O153:K−:H30 isolates from phylogroup D, expressed CTX-M-14, and were from young hospitalized patients with urinary tract infections (UTI).

Phenotype characteristics.

The ST131 and non-ST131 isolates did not differ significantly in the prevalence of biofilm production (5% versus 14%, respectively; P = 0.24) or production of alpha-hemolysin (<1% versus 1%) or enterohemolysin (0% versus 2.8%). No isolate produced verotoxin.

Susceptibility testing.

In general, coresistance to most of the tested non-beta-lactam agents was highly prevalent (57 to 100%), without significant differences between ST131 and non-ST131 isolates (Table 4). Resistance to quinolones, folate antagonists, tetracycline, and certain older aminoglycosides was most prevalent.

Table 4.

Prevalences of antimicrobial coresistance among 115 ST131 and non-ST131 ESBL-producing E. coli isolates from Copenhagen (2008-2009)a

| Antimicrobial agent | Prevalence [no. (%)] of antimicrobial resistance in ST group (nb) |

P valuec | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (115) | ST131 (44) | Non-ST131 (71) | ||

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 66 (57) | 18 (41) | 48 (68) | |

| Apramycin | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | |

| Chloramphenicol | 26 (23) | 1 (2) | 25 (35) | < 0.001 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 86 (75) | 41 (93) | 45 (63) | < 0.001 |

| Florfenicol | 13 (11) | 0 (0) | 13 (18) | 0.0045 |

| Gentamicin | 32 (28) | 7 (16) | 25 (35) | 0.03 |

| Nalidixic acid | 86 (75) | 41 (93) | 45 (63) | < 0.001 |

| Neomycin | 10 (9) | 0 (0%) | 10 (14) | 0.01 |

| Spectinomycin | 47 (41) | 22 (50) | 25 (35) | |

| Streptomycin | 89 (77) | 36 (82) | 53 (75) | |

| Sulfamethoxazole | 88 (77) | 38 (86) | 50 (70) | |

| Tetracycline | 83 (72) | 32 (73) | 51 (72) | |

| Trimethoprim | 81 (70) | 35 (80) | 46 (65) | |

All isolates were susceptible to colistin and meropenem and resistant to ampicillin, cefotaxime, and ceftiofur.

n, no. of isolates.

P values (ST131 vs. non-ST131), by Fisher's exact test (2-tailed), are shown where P < 0.05.

ST131 isolates were associated positively with resistance to naladixic acid and ciprofloxacin and negatively with resistance to gentamicin, neomycin, florfenicol, and chloramphenicol (Table 4). The overall median number of resistance characters was 9, with no difference between the ST131 and non-ST131 isolates.

Non-ST131 resistance-associated clonal groups.

Screening of the group D non-ST131 isolates for membership in the disseminated ST69 (clonal group A [CGA]) or CC31 (O15:K52:H1) clonal groups identified four presumptive CGA members, all from urine. All 4 were confirmed as ST69 by full MLST. Two of these (O17:K96:H18 with CTX-M-1 and O77:K96:H18 with CTX-M-15) produced biofilm. Additionally, one was O25:K51:H4 (resembling ST131), and one was O15:K52:H1 (resembling CC31), both with CTX-M-14.

DISCUSSION

In this molecular and serotyping survey of 115 unique ESBL isolates from Copenhagen (2008-2009), we found that ST131 was the single most prevalent clonal group overall, comprising 44 (38%) of the ESBL isolates. A similar fraction of ST131 among ESBL isolates was found in several international studies (24–26) and in a recent Danish study that, in contrast to our study, provided only limited characterization of the isolates (27).

The ST131 ESBL isolates were significantly associated with the O25, K100, and H4 antigens. The associations of ST131 with serogroup O25 and the H4 flagellar antigen were expected, since many studies have documented O25:H4 as the typical O:H serotype of ST131. In contrast, less is known about capsular antigens in ST131, largely because K typing is infrequently performed. We found seven different capsular antigens among the ST131 isolates, which to our knowledge is the largest diversity of K antigens reported for ST131 to date. The only relevant precedent is from a Norwegian study that identified 3 different K antigens (K100, K14, and K5) among its 9 ST131 isolates (28). Interestingly, most of the present K100-positive isolates were initially classified presumptively by PCR as K2 based on amplification with kpsM II primers and but not with kii or K15-specific primers (18). Other ST131 isolates that serologically were K2, K20,23, K22, and K98 yielded the same kps PCR results. This indicates that a broader range of capsular antigen-encoding genes is detected by this combination of PCR results than previously recognized (18).

We also found two ST131 isolates with serotype O16:K100:H5. Serogroup O16 ST131 isolates, which appear to be relatively uncommon, have been found recently in Australia (29) and Japan (30). However, to our knowledge this is the first report of the K- and H-antigen status of O16-positive ST131 isolates. Our two O16 ST131 isolates exhibited the K100 capsular antigen, which also was the most prevalent K antigen among the (majority) serogroup O25 ST131 isolates, and, unlike findings for other the ST131 isolates, the H5 flagellar antigen. These two isolates differed considerably from the O25:K100 isolates in the PFGE tree, implying a different subspecies phylogenetic background.

ST131 was initially considered to be particularly prevalent in community settings (1), but subsequent findings suggested otherwise (31). Here, ST131 was significantly associated with community acquisition, which accounted for 40/44 (91%) of ST131 isolates versus 53/71 (75%) of non-ST131 isolates (P < 0.001). This suggests established endemicity of ST131 in the Copenhagen community, with ongoing local transmission.

PFGE analysis of the 44 ST131 isolates (Fig. 1) showed considerable similarity among the CTX-M-15-positive isolates and, interestingly, also among the CTX-M-27-positive isolates. This suggests primarily clonal spread as the explanation for the high prevalence of these enzymes, rather than promiscuous horizontal transfer of the corresponding genetic determinants, which should distribute them broadly among pulsotypes. A future non-CTXM-15 ST131 clonal group outbreak might be a possibility.

E. coli CGA, from phylogenetic group D, was one of the first ExPEC clonal groups to be implicated in widespread dissemination and apparent outbreaks of antimicrobial-resistant extraintestinal infections (32). Only 4 CGA isolates were found among the present 109 ESBL isolates from extraintestinal sources, which is consistent with the paucity of prior reports of ESBL-producing CGA isolates (32–34). Interestingly, one MLST-confirmed CGA isolate with CTX-M-14 was serotype O15:H52:H1, which is classically associated with clonal complex CC31, a well-known disseminated and antimicrobial resistance-associated clonal group from phylogenetic group D (35) that has previously been reported to produce CTX-M-14 (10). Additionally, one CGA isolate exhibited serotype O25:K51:H4, mimicking ST131. This is consistent with a previous report from Spain of ST69 O25:H4 E. coli in river water (36). To our knowledge, the K51 capsular antigen has not been reported previously in relation to either ST131 or CGA. The antigenic diversity of both CGA and ST131 suggests that these clonal groups may be adapting in response to host immune pressure and poses potential challenges for future vaccine development, clinical diagnostics, and epidemiological studies.

It is well documented that ST131 is statistically associated with ExPEC status (17), as confirmed here. We also found significantly more virulence factor genes among ST131 members than for other ESBL E. coli isolates. This could reflect enhanced virulence and/or intestinal colonization and transmission capability for ST131 and likely partly explains why the ST131 clonal group has been so successful. Clinical extraintestinal E. coli isolates are not necessarily all ExPEC, since they may have been colonizing without causing disease or causing disease but in a compromised host whose defenses are easily overcome, requiring little intrinsic virulence on the organism's part. Given the extensive resistance profiles of the non-ST131 ESBL isolates and their primarily non-group B2 phylogenetic background, it is not surprising that only 41% were ExPEC. In contrast, the finding that nearly all ST131 ESBL isolates qualified as ExPEC conflicts with conventional dogma regarding an inverse relationship between resistance and virulence, further underscoring the distinctiveness of ST131.

Interestingly, two non-ST131 isolates of serotype O153:H30, from phylogroup D, with CTX-M-14, fulfilled molecular criteria for both ExPEC and EAEC, the latter being associated with diarrheagenic E. coli. Both isolates had a complete copy of pap, encoding P fimbriae. Both isolates originated with patients with UTI admitted to emergency departments. We recently reported an outbreak of UTI in Copenhagen caused by a clonal group of E. coli O78:H10 that both fulfilled molecular criteria for EAEC and contained multiple ExPEC virulence genes (37). Intriguingly, the outbreak strain's EAEC-specific virulence factors were found to increase its uropathogenicity (38). The present finding of antimicrobial-resistant EAEC strains causing UTI replicates the previous study's results, only now with the ESBL phenotype.

In conclusion, the ST131 pandemic multidrug-resistant (MDR) clonal group was the most prevalent clonal group among ESBL E. coli isolates in Copenhagen in 2008-2009 and was significantly associated with community acquisition, the O25, K100, and H4 antigens, ExPEC status, an extensive virulence gene repertoire, and CTX-M-15. Four CGA isolates were found among the present 109 ESBL isolates from extraintestinal sources. The antigenic diversity of both CGA and ST131 suggests that these clonal groups may be adapting in response to host immune pressure. Additionally, two non-ST131 (O153:K−:H30) urine isolates were found to qualify as both ExPEC and EAEC. These findings considerably expand the known range of capsular antigens in ST131, uniquely document ST131 isolates of serotype O16:K10:H5, provide additional evidence of MDR ExPEC isolates that are also EAEC, and confirm the high prevalence of ST131 as a community-associated, ESBL-positive pathogen in Copenhagen.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This material is based upon work supported by the Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs, grant no. 1 I01 CX000192 01 (to J.R.J.), and a research grant from Hillerød Hospital (to B.O.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 April 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00346-13.

REFERENCES

- 1. Rogers BA, Sidjabat HE, Paterson DL. 2011. Escherichia coli O25b-ST131: a pandemic, multiresistant, community-associated strain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peirano G, Pitout JD. 2010. Molecular epidemiology of Escherichia coli producing CTX-M beta-lactamases: the worldwide emergence of clone ST131 O25:H4. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 35:316–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Canton R, Coque TM. 2006. The CTX-M beta-lactamase pandemic. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:466–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Partridge SR, Zong Z, Iredell JR. 2011. Recombination in IS26 and Tn2 in the evolution of multiresistance regions carrying blaCTX-M-15 on conjugative IncF plasmids from Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:4971–4978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Friedman ND, Kaye KS, Stout JE, McGarry SA, Trivette SL, Briggs JP, Lamm W, Clark C, MacFarquhar J, Walton AL, Reller LB, Sexton DJ. 2002. Health care-associated bloodstream infections in adults: a reason to change the accepted definition of community-acquired infections. Ann. Intern. Med. 137:791–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Orskov F, Orskov I. 1984. Serotyping of Escherichia coli, p 43–112 In Bergan T. (ed), Methods in microbiology, vol. 14 Academic Press, London, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 7. Konowalchuk J, Speirs JI, Stavric S. 1977. Vero response to a cytotoxin of Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 18:775–779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Beutin L, Montenegro MA, Orskov I, Orskov F, Prada J, Zimmermann S, Stephan R. 1989. Close association of verotoxin (Shiga-like toxin) production with enterohemolysin production in strains of Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:2559–2564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lester CH, Olsen SS, Jakobsen L, Arpi M, Fuursted K, Hansen DS, Heltberg O, Holm A, Hojbjerg T, Jensen KT, Johansen HK, Justesen US, Kemp M, Knudsen JD, Roder B, Frimodt-Moller N, Hammerum AM. 2011. Emergence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Danish hospitals; this is in part explained by spread of two CTX-M-15 clones with multilocus sequence types 15 and 16 in Zealand. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 38:180–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cortes P, Blanc V, Mora A, Dahbi G, Blanco JE, Blanco M, Lopez C, Andreu A, Navarro F, Alonso MP, Bou G, Blanco J, Llagostera M. 2010. Isolation and characterization of potentially pathogenic antimicrobial-resistant Escherichia coli strains from chicken and pig farms in Spain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:2799–2805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dhanji H, Doumith M, Clermont O, Denamur E, Hope R, Livermore DM, Woodford N. 2010. Real-time PCR for detection of the O25b-ST131 clone of Escherichia coli and its CTX-M-15-like extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 36:355–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Johnson JR, Menard M, Johnston B, Kuskowski MA, Nichol K, Zhanel GG. 2009. Epidemic clonal groups of Escherichia coli as a cause of antimicrobial-resistant urinary tract infections in Canada, 2002 to 2004. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2733–2739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Johnson JR, Owens K, Manges AR, Riley LW. 2004. Rapid and specific detection of Escherichia coli clonal group A by gene-specific PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:2618–2622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Johnson JR, Owens KL, Clabots CR, Weissman SJ, Cannon SB. 2006. Phylogenetic relationships among clonal groups of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli as assessed by multi-locus sequence analysis. Microbes Infect. 8:1702–1713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Johnson JR, Stell AL. 2000. Extended virulence genotypes of Escherichia coli strains from patients with urosepsis in relation to phylogeny and host compromise. J. Infect. Dis. 181:261–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Johnson JR, Stell AL, Scheutz F, O'Bryan TT, Russo TA, Carlino UB, Fasching C, Kavle J, Van Dijk L, Gaastra E. 2000. Analysis of the F antigen-specific papA alleles of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli using a novel multiplex PCR-based assay. Infect. Immun. 68:1587–1599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Johnson JR, Murray AC, Gajewski A, Sullivan M, Snippes P, Kuskowski MA, Smith KE. 2003. Isolation and molecular characterization of nalidixic acid-resistant extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli from retail chicken products. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2161–2168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Johnson JR, O'Bryan TT. 2004. Detection of the Escherichia coli group 2 polysaccharide capsule synthesis Gene kpsM by a rapid and specific PCR-based assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1773–1776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Boisen N, Scheutz F, Rasko DA, Redman JC, Persson S, Simon J, Kotloff KL, Levine MM, Sow S, Tamboura B, Toure A, Malle D, Panchalingam S, Krogfelt KA, Nataro JP. 2012. Genomic characterization of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli from children in Mali. J. Infect. Dis. 205:431–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Clermont O, Johnson JR, Menard M, Denamur E. 2007. Determination of Escherichia coli O types by allele-specific polymerase chain reaction: application to the O types involved in human septicemia. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 57:129–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Clermont O, Dhanji H, Upton M, Gibreel T, Fox A, Boyd D, Mulvey MR, Nordmann P, Ruppe E, Sarthou JL, Frank T, Vimont S, Arlet G, Branger C, Woodford N, Denamur E. 2009. Rapid detection of the O25b-ST131 clone of Escherichia coli encompassing the CTX-M-15-producing strains. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64:274–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ribot EM, Fair MA, Gautom R, Cameron DN, Hunter SB, Swaminathan B, Barrett TJ. 2006. Standardization of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocols for the subtyping of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella, and Shigella for PulseNet. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 3:59–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tenover FC, Arbeit RD, Goering RV, Mickelsen PA, Murray BE, Persing DH, Swaminathan B. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233–2239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peirano G, Richardson D, Nigrin J, McGeer A, Loo V, Toye B, Alfa M, Pienaar C, Kibsey P, Pitout JD. 2010. High prevalence of ST131 isolates producing CTX-M-15 and CTX-M-14 among extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolates from Canada. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:1327–1330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Coelho A, Mora A, Mamani R, Lopez C, Gonzalez-Lopez JJ, Larrosa MN, Quintero-Zarate JN, Dahbi G, Herrera A, Blanco JE, Blanco M, Alonso MP, Prats G, Blanco J. 2011. Spread of Escherichia coli O25b:H4-B2-ST131 producing CTX-M-15 and SHV-12 with high virulence gene content in Barcelona (Spain). J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:517–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Johnson JR, Urban C, Weissman SJ, Jorgensen JH, Lewis JS, II, Hansen G, Edelstein PH, Robicsek A, Cleary T, Adachi J, Paterson D, Quinn J, Hanson ND, Johnston BD, Clabots C, Kuskowski MA, Investigators AMERECUS 2012. Molecular epidemiological analysis of Escherichia coli sequence type ST131 (O25:H4) and blaCTX-M-15 among extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing E. coli from the United States, 2000 to 2009. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:2364–2370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nielsen JB, Albayati A, Jorgensen RL, Hansen KH, Lundgren B, Schonning K. 2013. An abbreviated MLVA identifies Escherichia coli ST131 as the major extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing lineage in the Copenhagen area. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 32:431–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Naseer U, Haldorsen B, Tofteland S, Hegstad K, Scheutz F, Simonsen GS, Sundsfjord A, Norwegian ESBL Study Group 2009. Molecular characterization of CTX-M-15-producing clinical isolates of Escherichia coli reveals the spread of multidrug-resistant ST131 (O25:H4) and ST964 (O102:H6) strains in Norway. APMIS 117:526–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kudinha T, Kong F, Johnson JR, Andrew SD, Anderson P, Gilbert GL. 2012. Multiplex PCR-based reverse line blot assay for simultaneous detection of 22 virulence genes in uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:1198–1202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Matsumura Y, Yamamoto M, Nagao M, Hotta G, Matsushima A, Ito Y, Takakura S, Ichiyama S, on behalf of the Kyoto-Shiga Clinical Microbiology Study Group 2012. Emergence and spread of B2-ST131-O25b, B2-ST131-O16 and D-ST405 clonal groups among extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in Japan. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:2612–2620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Croxall G, Hale J, Weston V, Manning G, Cheetham P, Achtman M, McNally A. 2011. Molecular epidemiology of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli isolates from a regional cohort of elderly patients highlights the prevalence of ST131 strains with increased antimicrobial resistance in both community and hospital care settings. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:2501–2508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Johnson JR, Murray AC, Kuskowski MA, Schubert S, Prere MF, Picard B, Colodner R, Raz R, Trans-Global Initiative for Antimicrobial Resistance Initiative (TIARA) Investigators 2005. Distribution and characteristics of Escherichia coli clonal group A. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:141–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pitout JD, Laupland KB, Church DL, Menard ML, Johnson JR. 2005. Virulence factors of Escherichia coli isolates that produce CTX-M-type extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4667–4670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tartof SY, Solberg OD, Manges AR, Riley LW. 2005. Analysis of a uropathogenic Escherichia coli clonal group by multilocus sequence typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:5860–5864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Olesen B, Scheutz F, Menard M, Skov MN, Kolmos HJ, Kuskowski MA, Johnson JR. 2009. Three-decade epidemiological analysis of Escherichia coli O15:K52:H1. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:1857–1862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Colomer-Lluch M, Mora A, Lopez C, Mamani R, Dahbi G, Marzoa J, Herrera A, Viso S, Blanco JE, Blanco M, Alonso MP, Jofre J, Muniesa M, Blanco J. 7 December 2012. Detection of quinolone-resistant Escherichia coli isolates belonging to clonal groups O25b:H4-B2-ST131 and O25b:H4-D-ST69 in raw sewage and river water in Barcelona, Spain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. doi:10.1093/jac/dks477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Olesen B, Scheutz F, Andersen RL, Menard M, Boisen N, Johnston B, Hansen DS, Krogfelt KA, Nataro JP, Johnson JR. 2012. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli O78:H10, the cause of an outbreak of urinary tract Infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:3703–3711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Boll EJ, Struve C, Olesen B, Stahlhut SG, Krogfelt KA. 28 January 2013. Role of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli virulence factors in uropathogenesis. Infect. Immun. doi:10.1128/IAI.01376-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.