Abstract

Aspergillus fumigatus complex comprises A. fumigatus and other morphologically indistinguishable cryptic species. We retrospectively studied 362 A. fumigatus complex isolates (353 samples) from 150 patients with proven or probable invasive aspergillosis or aspergilloma (2, 121, and 6 samples, respectively) admitted to the hospital from 1999 to 2011. Isolates were identified using the β-tubulin gene, and only 1 isolate per species found in each sample was selected. Antifungal susceptibility to azoles was determined using the CLSI M38-A2 procedure. Isolates were considered resistant if they showed an MIC above the breakpoints for itraconazole, voriconazole, or posaconazole (>2, >2, or >0.5 μg/ml). Most of the samples yielded only 1 species (A. fumigatus [n = 335], A. novofumigatus [n = 4], A. lentulus [n = 3], A. viridinutans [n = 1], and Neosartorya udagawae [n = 1]). The remaining samples yielded a combination of 2 species. Most of the patients were infected by a single species (A. fumigatus [n = 143] or A. lentulus [n = 2]). The remaining 5 patients were coinfected with multiple A. fumigatus complex species, although A. fumigatus was always involved; 4 of the 5 patients were diagnosed in 2009 or later. Cryptic species were less susceptible than A. fumigatus. The frequency of resistance among A. fumigatus complex and A. fumigatus to itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole was 2.5 and 0.3%, 3.1 and 0.3%, and 4.2 and 1.8%, respectively, in the per-isolate analysis and 1.3 and 0.7%, 2.6 and 0.7%, and 6 and 4% in the per-patient analysis. Only 1 of the 6 A. fumigatus isolates in which the cyp51A gene was sequenced had a mutation at position G448. The proportion of patients infected by azole-resistant A. fumigatus isolates was low.

INTRODUCTION

Invasive aspergillosis (IA), an opportunistic infection that affects patients with different degrees of immunosuppression (1–7), is usually treated with voriconazole (8). Patients at high risk for IA receive antifungal prophylaxis with posaconazole and itraconazole (9). These agents show potent in vitro activity against clinical isolates of the so-called Aspergillus fumigatus complex (10–13).

The A. fumigatus complex includes several morphologically indistinguishable species, such as A. fumigatus sensu stricto (referred to here as A. fumigatus), and the cryptic species A. lentulus, A. novofumigatus, A. viridinutans, and Neosartorya udagawae (2, 6, 14). Cryptic species show reduced susceptibility to azoles (15).

Resistance in A. fumigatus isolates is conferred mainly by specific point mutations in the cyp51A gene (16–22). Recent reports from different European countries, including the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and France, have indicated an increase in the frequency of A. fumigatus isolates showing phenotypic resistance to itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole (23–28). However, in most studies, only 1 colony per patient was studied and cryptic species were excluded (24–27, 29, 30). The selection of a single colony per sample would lead us to underestimate azole resistance or the presence of cryptic species if they are present in a low proportion.

No recent data are available on the susceptibility to azoles of A. fumigatus complex isolates collected in Spain. We studied the antifungal susceptibility of a large collection of A. fumigatus complex isolates from 150 patients with proven or probable IA or aspergilloma admitted to a large tertiary hospital in Madrid, Spain.

(This study was presented in part at the 23rd European Congress on Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Berlin, Germany, 2013 [poster P-996].)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Hospital description and study population.

This study was carried out at a large teaching hospital serving a population of approximately 715,000 inhabitants in the city of Madrid. The institution cares for all types of patients at risk of acquiring aspergillosis, including solid organ and bone marrow transplant recipients and patients with hematological malignancies, HIV infection, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

We selected 150 patients with diseases caused by A. fumigatus complex admitted to the hospital from 1999 to 2011. Six had aspergilloma and 144 had IA (proven, n = 23; probable, n = 121) according to the revised criteria of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (31, 32). Patients with COPD fulfilled Bulpa's criteria (31, 32). The clinical manifestations of IA were lower respiratory tract infection (n = 136), sinusitis (n = 3), wound infection (n = 8), central nervous system infection (n = 8), and other conditions (n = 3). The main underlying conditions of the patients were hematological cancer (12.8%), solid cancer (14.7%), cirrhosis (9.3%), COPD (50%), neutropenia (9.3%), and immunosuppression in solid-organ recipients (13.3%).

Samples and isolates.

We studied 353 samples from the above-mentioned 150 patients (2.3 samples per patient) from whom A. fumigatus complex was isolated. Samples from the lower respiratory tract (n = 306), biopsy specimens (n = 16), wounds (n = 23), and other sources (n = 8) were cultured on both bacterial and mycological media. In 91 of the 150 patients, 2 or more samples were studied, and the mean number of days between the first and the last sample was 16.5. All colonies resembling A. fumigatus complex that grew on the culture plates were subcultured and further studied independently, yielding 837 isolates (2.3 samples per patient, 2.4 isolates per sample, and 5.6 isolates per patient).

The 837 isolates were identified by amplifying and sequencing the β-tubulin gene (33). Genomic DNA was extracted from conidia suspensions with a DNeasy tissue kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) and initially treated with lyticase (Sigma-Aldrich Corporation, St. Louis, MO) for 2 h at 37°C. PCR amplifications were carried out using the two pairs of primers βtub1 and βtub2 (34). We used the same conditions and temperature profiles for both independent amplification regions. Briefly, amplifications were performed in 50 μl of reaction solution containing 50 mM KCl, 15 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 1.5 mM MgCl2, a 0.2 mM concentration of each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP), 0.5 μM for each pair of primers, 25 ng genomic DNA, and 2.5 units of AmpliTaqGold DNA polymerase LD (Applied Biosystems). The temperature profiles chosen for the amplifications were as follows: an initial step of 5 min at 94°C, 35 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 45 s at 50°C, and 2 min at 72°C, and a final step of 5 min at 72°C. PCRs were carried out in a T-Gradient thermocycler (Biometra, Germany). PCR products were purified using an Illustra GFX PCR DNA and gel band purification kit (Amersham Bioscience UK, Ltd., Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). Double-stranded DNA sequencing of the PCR products was performed using a BigDye Terminator v3.1 sequencing kit and capillary electrophoresis with a 3130xl analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Inc.). A homology search of all the sequenced amplicons was performed through NCBI BLAST to determine whether the sequences matched A. fumigatus or the cryptic species. The sequences of the different A. fumigatus complex species were obtained from BLAST and used as controls.

We selected 362 of the 837 isolates according to the following criteria: (i) only 1 colony per species found was selected from samples with 2 different species; (ii) the isolate showing the highest MIC was chosen in cases of multiple isolates of the same species. From 1999 to 2005, only 1 colony per sample was stored, and isolates were collected retrospectively. From 2006 onward, all visible colonies grown in the media were stored, and isolates were collected prospectively.

Antifungal susceptibility and sequencing of the A. fumigatus cyp51A gene.

Antifungal susceptibility to itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole was determined using the CLSI M38-A2 procedure (35). The final concentration of the antifungal agents tested ranged from 0.003 μg/ml to 8 μg/ml.

A. fumigatus complex isolates were considered resistant if they showed an MIC above the breakpoints recently proposed by Verweij et al. (36) (>2 μg/ml for itraconazole and voriconazole and >0.5 μg/ml for posaconazole). In the absence of specific breakpoints for the cryptic species, we applied the breakpoints chosen for A. fumigatus. We calculated the rate of azole resistance for A. fumigatus complex and for A. fumigatus; the rate of resistance was shown per isolate and per patient. The percentage of isolates showing an MIC above the epidemiological cutoff values (ECVs) proposed by Pfaller et al. (37) and Espinel-Ingroff et al. (38) was calculated (>1 μg/ml for itraconazole and voriconazole and >0.5 μg/ml for posaconazole). We obtained the cyp51A gene sequence (39) of A. fumigatus isolates that were considered resistant or that showed an MIC above the ECVs.

RESULTS

Distribution of A. fumigatus complex species found in the samples.

Most of the samples yielded only 1 species (A. fumigatus [n = 335], A. novofumigatus [n = 4], A. lentulus [n = 3], A. viridinutans [n = 1], and N. udagawae [n = 1]). In the remaining samples, a combination of 2 species was present (A. fumigatus and A. lentulus [n = 6], A. fumigatus and A. novofumigatus [n = 1], A. fumigatus and N. udagawae [n = 1], and A. novofumigatus and A. viridinutans [n = 1]). A. fumigatus was found in 97% of the samples.

Species of A. fumigatus complex causing aspergillosis.

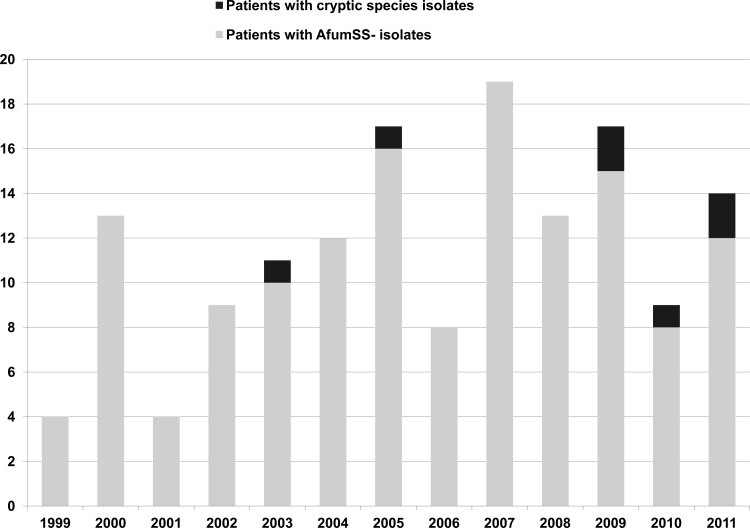

Of the 150 patients, 143 were infected exclusively by A. fumigatus, 2 were infected by A. lentulus, and the remaining 5 were coinfected by A. fumigatus plus other cryptic species (Table 1). The 7 patients infected by cryptic species had heterogeneous underlying predisposing conditions, mainly solid or hematological cancer, and were mostly diagnosed from 2009 onward (Fig. 1). Males accounted for 43%, and all had invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Despite frequent therapy with combined antifungal agents, the mortality rate was invariably high (86%). The prognosis was poor in patients receiving azoles or amphotericin B. Serum galactomannan was studied in 5 patients; the result was positive in 4. Isolation of cryptic species proved to be a surrogate marker of poor prognosis in the patients infected.

Table 1.

Summary of data for the 7 patients infected by cryptic species of A. fumigatus complexa

| Code | Yr of diagnosis | Underlying condition(s) | Antifungal treatment | Outcome | Species found | MIC (μg/ml) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITC | VRC | POS | ||||||

| 1 | 2003 | Corticosteroids | AMB | Poor | A. lentulus | 1 | 1 | 0.5 |

| 2 | 2005 | Hematological cancer + COPD | VRC + CAS | Poor | A. fumigatus | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 |

| N. udagawae | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | |||||

| 3 | 2009 | COPD | VRC | Poor | A. lentulus | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| 4 | 2009 | Cirrhosis + solid cancer | VRC + AMB | Poor | A. fumigatus | 1 | 0.5 | 0.125 |

| A. lentulus | 1 | 2 | 0.5 | |||||

| 5 | 2010 | Hematological cancer | MYC followed by VRC followed by AMB + CAS | Poor | A. fumigatus | 1 | 1 | 0.5 |

| A. lentulus | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||

| A. novofumigatus | 16 | 16 | 1 | |||||

| A. viridinutans | 4 | 4 | 0.5 | |||||

| 6 | 2011 | Solid cancer | VRC followed by CAS followed by POS | Favorable | A. fumigatus | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| A. lentulus | 2 | 4 | 0.5 | |||||

| 7 | 2011 | Solid cancer | AMB + MYC + VRC | Poor | A. fumigatus | 1 | 0.5 | 0.25 |

| A. lentulus | 2 | 4 | 0.5 | |||||

| N. udagawae | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | |||||

ICU, intensive care unit; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GM, galactomannan; ITC, itraconazole; VRC, voriconazole; POS, posaconazole; AMB, amphotericin B; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CAS, caspofungin; MYC, micafungin.

Fig 1.

Number of patients with invasive aspergillosis during the study period. Patients were grouped according to infection with A. fumigatus sensu stricto (AfumSS) or cryptic species.

Antifungal susceptibility and cyp51A gene sequencing.

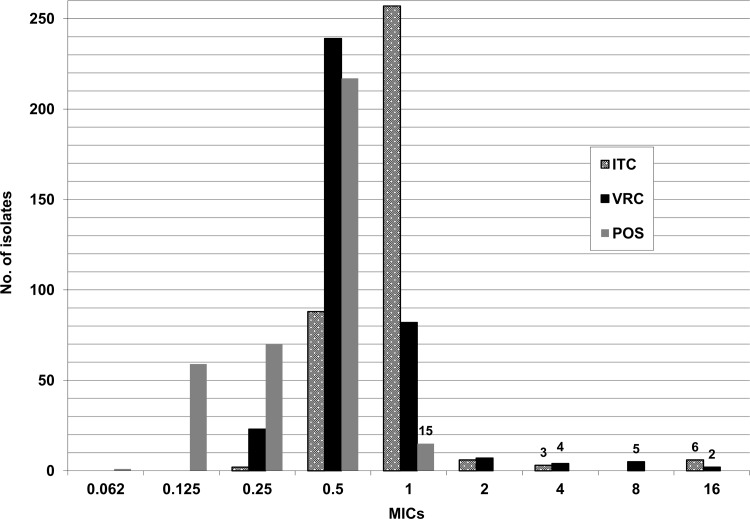

The overall rates of azole resistance of A. fumigatus complex and A. fumigatus to 1 or more azoles were 4.2% and 1.8%. The frequencies of resistance of A. fumigatus complex and A. fumigatus were as follows: itraconazole, 2.5 and 0.3%; voriconazole, 3.1 and 0.3%; and posaconazole, 4.2 and 1.8% (Fig. 2). The percentages of isolates showing MICs above the ECVs for itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole, respectively, were 4.2%, 5%, and 4.2%.

Fig 2.

MIC distribution of itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole for the 362 A. fumigatus complex isolates. Resistant isolates were defined as those with an MIC of voriconazole or itraconazole of >2 μg/ml or an MIC of posaconazole of >0.5 μg/ml.

Fifteen A. fumigatus complex isolates were resistant to posaconazole (A. novofumigatus, n = 6; A. lentulus, n = 3; and A. fumigatus, n = 6). The cyp51A gene was sequenced in the 6 A. fumigatus isolates showing resistance to 1 or more azoles, and a point mutation leading to the G448S amino acid substitution was found in 1 isolate. The remaining 5 isolates showed a wild-type cyp51A gene sequence, and only posaconazole showed an MIC above the breakpoints (1 μg/ml).

Isolates of A. fumigatus were more susceptible to azoles than isolates of cryptic species (Table 2). Among the cryptic species, N. udagawae was the most susceptible (Table 1, patients 2 and 7). In patients with multiple isolates from the same species, no differences in antifungal susceptibility were found between the isolates (data not shown).

Table 2.

Antifungal susceptibility of the isolates studied to itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole

| Organism | No. of isolates | MIC90 (range) (μg/ml) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Itraconazole | Voriconazole | Posaconazole | ||

| A. fumigatus complex | 362 | 1 (0.25–16) | 1 (0.25–16) | 0.5 (0.06–1) |

| A. fumigatus | 343 | 1 (0.25–4) | 1 (0.25–16) | 0.5 (0.06–1) |

| Cryptic species | 19 | 16 (1–16) | 8 (1–16) | 1 (0.25–1) |

The percentages of patients infected by itraconazole-, voriconazole-, and posaconazole-resistant A. fumigatus complex and A. fumigatus isolates were 1.3 and 0.7%, 2.6 and 0.7%, and 6 and 4%, respectively. The percentage of patients infected by an isolate resistant to 1 or more azoles was 6.7%.

DISCUSSION

The spectrum of patients at risk of IA has expanded, with the result that azoles are increasingly used for the treatment and prevention of IA. In some countries, the increase in the number of azole-resistant A. fumigatus isolates has restricted management of patients with this devastating disease.

In the Netherlands, the percentage of patients infected by azole-resistant Aspergillus has been growing since 2000 and now stands at 12% (24, 29). Most were infected by isolates showing the “typical” Dutch mutation in the cyp51A gene, which consists of a codon change yielding an amino acid substitution in L98H and the insertion of a 34-bp tandem repeat in the promoter of the cyp51A gene (19). The use of azoles in agriculture has been proposed as the source of these resistant isolates (40).

In the United Kingdom, Howard et al. (26) illustrated the development of secondary resistance in up to 28% of A. fumigatus isolates from a series of patients previously treated with azoles (mostly itraconazole) (26). As expected, isolates from these patients showed several mutations in the cyp51A gene. Azole resistance has also been reported—albeit sporadically—in France (41), India (30), Japan (42), China (43), Denmark (44), Sweden (45), Norway (46), and Germany (47).

Our results showed that 6.7% of patients were infected by resistant A. fumigatus complex isolates. When only A. fumigatus was considered, azole resistance was found in 6 patients (4%); the isolates from 5 patients were considered resistant only to posaconazole, and the MIC (1 μg/ml) was only a 1-fold dilution above the breakpoint. Furthermore, the cyp51A gene sequence was wild type, and most of the patients responded clinically to azoles. A potential explanation could be that we studied antifungal susceptibility using CLSI methods but breakpoints proposed for the EUCAST method. Further evaluation of the breakpoints proposed for posaconazole is required. The isolates from the remaining patient showed a mutation in the cyp51A gene, thus demonstrating the presence of resistance. The patient had been living in another city and was transferred to our hospital to be treated for IA in 2011 (48), suggesting that resistance to azoles in A. fumigatus isolates collected in our hospital is minimal (0.7% of patients infected by this species).

None of our isolates showed the typical Dutch mutation that is emerging in other areas. The low rate of azole resistance detected could be explained by the kind of patients included, who were mostly treated for acute forms of IA. However, a high prevalence of A. fumigatus isolates carrying the L98 mutation in patients with chronic conditions, such as cystic fibrosis, has been reported (28, 49, 50). Another possible explanation is that resistant isolates in the environment are infrequent: other authors were unable to detect azole-resistant A. fumigatus isolates in samples collected in Madrid or in the area around Madrid (10, 51).

We began the exhaustive collection of isolates in 2006, when all available colonies resembling A. fumigatus complex were isolated and identified using morphological and molecular procedures. However, we remained unable to detect azole-resistant A. fumigatus isolates that would have been missed if a single colony had been selected. In contrast, we were able to simultaneously isolate A. fumigatus together with other cryptic species in 9 samples. The number of patients infected by cryptic species has been growing since 2009, possibly owing to the large number of isolates collected during this period. Nevertheless, patients infected by cryptic species, either alone or together with A. fumigatus, had a poor prognosis despite antifungal treatment.

We did not use azole-containing plates to screen resistant isolates, a procedure commonly used in other studies (24, 29). Unfortunately, the antifungal susceptibility of the isolates before contact with itraconazole was not reported in those studies. It should be noted that the azole MICs for isolates grown on plates containing itraconazole are higher than the MICs for the same isolates grown on itraconazole-free plates (52). The MICs of the isolates reported here were not affected by previous exposure to azoles.

Our study is subject to a series of limitations. We only analyzed cultivable isolates. A recent report showed a high percentage of azole resistance in noncultivable A. fumigatus in lower-respiratory-tract samples after DNA amplification (53). As we included isolates from only a single hospital, our findings might not reflect the situation of other areas in Spain. The number of cryptic species found in our study is low; however, the increase in the number of cases of IA caused by these isolates warrants further attention. As this is not a population-based study, the precise prevalence of azole resistance is unknown. Collection of isolates was not consistent during the study period—only 1 colony per sample was collected from 1999 to 2006—and the presence of cryptic species during this period may have been underestimated. However, the emergence of cryptic species was more evident from 2009 onwards, although the study of multiple colonies per sample began in 2006 and 2 cases of IA were diagnosed before 2006.

We conclude that the rate of azole resistance is very low in A. fumigatus strains isolated from patients admitted to our hospital. The number of cryptic species isolated was also low but has been increasing since 2009. It is important to study several isolates per patient in order to reveal the presence of cases of coinfection by cryptic species.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Thomas O'Boyle for editing and proofreading the article.

This study does not present any conflicts of interest for its authors.

This study was partially financed by grant CP09/00055 from the Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria (FIS, Instituto de Salud Carlos III) and Gilead Sciences. Jesús Guinea (MS09/00055) and Pilar Escribano (CD09/00230) are supported by the FIS.

We are grateful to Ainhoa Simón Zárate, who holds a grant from the FIS (Línea Instrumental Secuenciación), for her participation in the sequencing analysis. The 3130xl Genetic Analyzer was partially financed by grants from the FIS (IF01-3624, IF08-36173).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 29 April 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Kontoyiannis DP, Marr KA, Park BJ, Alexander BD, Anaissie EJ, Walsh TJ, Ito J, Andes DR, Baddley JW, Brown JM, Brumble LM, Freifeld AG, Hadley S, Herwaldt LA, Kauffman CA, Knapp K, Lyon GM, Morrison VA, Papanicolaou G, Patterson TF, Perl TM, Schuster MG, Walker R, Wannemuehler KA, Wingard JR, Chiller TM, Pappas PG. 2010. Prospective surveillance for invasive fungal infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, 2001–2006: overview of the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network (TRANSNET) Database. Clin. Infect. Dis. 50:1091–1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Neofytos D, Horn D, Anaissie E, Steinbach W, Olyaei A, Fishman J, Pfaller M, Chang C, Webster K, Marr K. 2009. Epidemiology and outcome of invasive fungal infection in adult hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: analysis of Multicenter Prospective Antifungal Therapy (PATH) Alliance registry. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:265–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Neofytos D, Fishman JA, Horn D, Anaissie E, Chang CH, Olyaei A, Pfaller M, Steinbach WJ, Webster KM, Marr KA. 2010. Epidemiology and outcome of invasive fungal infections in solid organ transplant recipients. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 12:220–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Denning DW. 2006. Aspergillus and aspergillosis—progress on many fronts. Med. Mycol. 44(Suppl.):1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pagano L, Caira M, Candoni A, Offidani M, Martino B, Specchia G, Pastore D, Stanzani M, Cattaneo C, Fanci R, Caramatti C, Rossini F, Luppi M, Potenza L, Ferrara F, Mitra ME, Fadda RM, Invernizzi R, Aloisi T, Picardi M, Bonini A, Vacca A, Chierichini A, Melillo L, de Waure C, Fianchi L, Riva M, Leone G, Aversa F, Nosari A. 2010. Invasive aspergillosis in patients with acute myeloid leukemia: SEIFEM-2008 registry study. Haematologica 95:644–650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Guinea J, Torres-Narbona M, Gijón P, Muñoz P, Pozo F, Peláez T, de Miguel J, Bouza E. 2010. Pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: incidence, risk factors, and outcome. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:870–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Singh N, Husain S. 2009. Invasive aspergillosis in solid organ transplant recipients. Am. J. Transplant 9(Suppl. 4):S180–S191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Herbrecht R, Denning DW, Patterson TF, Bennett JE, Greene RE, Oestmann JW, Kern WV, Marr KA, Ribaud P, Lortholary O, Sylvester R, Rubin RH, Wingard JR, Stark P, Durand C, Caillot D, Thiel E, Chandrasekar PH, Hodges MR, Schlamm HT, Troke PF, de Pauw B. 2002. Voriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary therapy of invasive aspergillosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 347:408–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cornely OA, Maertens J, Winston DJ, Perfect J, Ullmann AJ, Walsh TJ, Helfgott D, Holowiecki J, Stockelberg D, Goh YT, Petrini M, Hardalo C, Suresh R, Angulo-Gonzalez D. 2007. Posaconazole vs. fluconazole or itraconazole prophylaxis in patients with neutropenia. N. Engl. J. Med. 356:348–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guinea J, Peláez T, Alcalá L, Ruiz-Serrano MJ, Bouza E. 2005. Antifungal susceptibility of 596 Aspergillus fumigatus strains isolated from outdoor air, hospital air, and clinical samples: analysis by site of isolation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:3495–3497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sabatelli F, Patel R, Mann PA, Mendrick CA, Norris CC, Hare R, Loebenberg D, Black TA, McNicholas PM. 2006. In vitro activities of posaconazole, fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, and amphotericin B against a large collection of clinically important molds and yeasts. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2009–2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cuenca-Estrella M, Gómez-López A, Mellado E, Buitrago MJ, Monzón A, Rodríguez-Tudela JL. 2006. Head-to-head comparison of the activities of currently available antifungal agents against 3,378 Spanish clinical isolates of yeasts and filamentous fungi. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:917–921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Peláez T, Alvarez-Pérez S, Mellado E, Serrano D, Valerio M, Blanco JL, García ME, Muñoz P, Cuenca-Estrella M, Bouza E. 2013. Invasive aspergillosis caused by cryptic Aspergillus species: a report of two consecutive episodes in a patient with leukemia. J. Med. Microbiol. 62:474–478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pappas PG, Alexander BD, Andes DR, Hadley S, Kauffman CA, Freifeld A, Anaissie EJ, Brumble LM, Herwaldt L, Ito J, Kontoyiannis DP, Lyon GM, Marr KA, Morrison VA, Park BJ, Patterson TF, Perl TM, Oster RA, Schuster MG, Walker R, Walsh TJ, Wannemuehler KA, Chiller TM. 2010. Invasive fungal infections among organ transplant recipients: results of the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network (TRANSNET). Clin. Infect. Dis. 50:1101–1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Balajee SA, Gribskov JL, Hanley E, Nickle D, Marr KA. 2005. Aspergillus lentulus sp. nov., a new sibling species of A. fumigatus. Eukaryot. Cell 4:625–632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Díaz-Guerra TM, Mellado E, Cuenca-Estrella M, Rodríguez-Tudela JL. 2003. A point mutation in the 14alpha-sterol demethylase gene cyp51A contributes to itraconazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1120–1124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mellado E, García-Effrón G, Alcázar-Fuoli L, Cuenca-Estrella M, Rodríguez-Tudela JL. 2004. Substitutions at methionine 220 in the 14alpha-sterol demethylase (Cyp51A) of Aspergillus fumigatus are responsible for resistance in vitro to azole antifungal drugs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2747–2750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Howard SJ, Webster I, Moore CB, Gardiner RE, Park S, Perlin DS, Denning DW. 2006. Multi-azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 28:450–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mellado E, García-Effrón G, Alcázar-Fuoli L, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE, Cuenca-Estrella M, Rodríguez-Tudela JL. 2007. A new Aspergillus fumigatus resistance mechanism conferring in vitro cross-resistance to azole antifungals involves a combination of cyp51A alterations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:1897–1904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Camps SM, van der Linden JW, Li Y, Kuijper EJ, van Dissel JT, Verweij PE, Melchers WJ. 2012. Rapid induction of multiple resistance mechanisms in Aspergillus fumigatus during azole therapy: a case study and review of the literature. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:10–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bellete B, Raberin H, Morel J, Flori P, Hafid J, Manhsung RT. 2010. Acquired resistance to voriconazole and itraconazole in a patient with pulmonary aspergilloma. Med. Mycol. 48:197–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kuipers S, Bruggemann RJ, de Sevaux RG, Heesakkers JP, Melchers WJ, Mouton JW, Verweij PE. 2011. Failure of posaconazole therapy in a renal transplant patient with invasive aspergillosis due to Aspergillus fumigatus with attenuated susceptibility to posaconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:3564–3566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Verweij PE, Mellado E, Melchers WJ. 2007. Multiple-triazole-resistant aspergillosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 356:1481–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Snelders E, van der Lee HA, Kuijpers J, Rijs AJ, Varga J, Samson RA, Mellado E, Donders AR, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE. 2008. Emergence of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus and spread of a single resistance mechanism. PLoS Med. 5:e219 doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0050219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Snelders E, Huis in 't Veld RA, Rijs AJ, Kema GH, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE. 2009. Possible environmental origin of resistance of Aspergillus fumigatus to medical triazoles. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:4053–4057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Howard SJ, Cerar D, Anderson MJ, Albarrag A, Fisher MC, Pasqualotto AC, Laverdiere M, Arendrup MC, Perlin DS, Denning DW. 2009. Frequency and evolution of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus associated with treatment failure. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15:1068–1076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bueid A, Howard SJ, Moore CB, Richardson MD, Harrison E, Bowyer P, Denning DW. 2010. Azole antifungal resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: 2008 and 2009. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 65:2116–2118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Morio F, Aubin GG, Danner-Boucher I, Haloun A, Sacchetto E, Garcia-Hermoso D, Bretagne S, Miegeville M, Le Pape P. 2012. High prevalence of triazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus, especially mediated by TR/L98H, in a French cohort of patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:1870–1873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van der Linden JW, Snelders E, Kampinga GA, Rijnders BJ, Mattsson E, Debets-Ossenkopp YJ, Kuijper EJ, Van Tiel FH, Melchers WJ, Verweij PE. 2011. Clinical implications of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus, The Netherlands, 2007–2009. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17:1846–1854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chowdhary A, Kathuria S, Randhawa HS, Gaur SN, Klaassen CH, Meis JF. 2012. Isolation of multiple-triazole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus strains carrying the TR/L98H mutations in the cyp51A gene in India. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:362–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP, Stevens DA, Edwards JE, Calandra T, Pappas PG, Maertens J, Lortholary O, Kauffman CA, Denning DW, Patterson TF, Maschmeyer G, Bille J, Dismukes WE, Herbrecht R, Hope WW, Kibbler CC, Kullberg BJ, Marr KA, Munoz P, Odds FC, Perfect JR, Restrepo A, Ruhnke M, Segal BH, Sobel JD, Sorrell TC, Viscoli C, Wingard JR, Zaoutis T, Bennett JE. 2008. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin. Infect. Dis. 46:1813–1821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bulpa P, Dive A, Sibille Y. 2007. Invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur. Respir. J. 30:782–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Balajee SA, Borman AM, Brandt ME, Cano J, Cuenca-Estrella M, Dannaoui E, Guarro J, Haase G, Kibbler CC, Meyer W, O'Donnell K, Petti CA, Rodríguez-Tudela JL, Sutton D, Velegraki A, Wickes BL. 2009. Sequence-based identification of Aspergillus, Fusarium, and Mucorales species in the clinical mycology laboratory: where are we and where should we go from here? J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:877–884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Staab JF, Balajee SA, Marr KA. 2009. Aspergillus section Fumigati typing by PCR-restriction fragment polymorphism. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:2079–2083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of filamentous fungi. Approved standard. CLSI document M38-A2. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA [Google Scholar]

- 36. Verweij PE, Howard SJ, Melchers WJ, Denning DW. 2009. Azole-resistance in Aspergillus: proposed nomenclature and breakpoints. Drug Resist. Updat. 12:141–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Ghannoum MA, Rex JH, Alexander BD, Andes D, Brown SD, Chaturvedi V, Espinel-Ingroff A, Fowler CL, Johnson EM, Knapp CC, Motyl MR, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Sheehan DJ, Walsh TJ. 2009. Wild-type MIC distribution and epidemiological cutoff values for Aspergillus fumigatus and three triazoles as determined by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute broth microdilution methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3142–3146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Espinel-Ingroff A, Diekema DJ, Fothergill A, Johnson E, Peláez T, Pfaller MA, Rinaldi MG, Cantón E, Turnidge J. 2010. Wild-type MIC distributions and epidemiological cutoff values for the triazoles and six Aspergillus spp. for the CLSI broth microdilution method (M38-A2 document). J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:3251–3257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Escribano P, Recio S, Peláez T, Bouza E, Guinea J. 2011. Aspergillus fumigatus strains with mutations in the cyp51A gene do not always show phenotypic resistance to itraconazole, voriconazole, or posaconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:2460–2462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Verweij PE, Snelders E, Kema GH, Mellado E, Melchers WJ. 2009. Azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: a side-effect of environmental fungicide use? Lancet Infect. Dis. 9:789–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Alanio A, Sitterle E, Liance M, Farrugia C, Foulet F, Botterel F, Hicheri Y, Cordonnier C, Costa JM, Bretagne S. 2011. Low prevalence of resistance to azoles in Aspergillus fumigatus in a French cohort of patients treated for haematological malignancies. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:371–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tashiro M, Izumikawa K, Minematsu A, Hirano K, Iwanaga N, Ide S, Mihara T, Hosogaya N, Takazono T, Morinaga Y, Nakamura S, Kurihara S, Imamura Y, Miyazaki T, Nishino T, Tsukamoto M, Kakeya H, Yamamoto Y, Yanagihara K, Yasuoka A, Tashiro T, Kohno S. 2012. Antifungal susceptibilities of Aspergillus fumigatus clinical isolates obtained in Nagasaki, Japan. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:584–587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lockhart SR, Frade JP, Etienne KA, Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Balajee SA. 2011. Azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus isolates from the ARTEMIS global surveillance study is primarily due to the TR/L98H mutation in the cyp51A gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:4465–4468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mortensen KL, Johansen HK, Fuursted K, Knudsen JD, Gahrn-Hansen B, Jensen RH, Howard SJ, Arendrup MC. 2011. A prospective survey of Aspergillus spp. in respiratory tract samples: prevalence, clinical impact and antifungal susceptibility. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 30:1355–1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chryssanthou E. 1997. In vitro susceptibility of respiratory isolates of Aspergillus species to itraconazole and amphotericin B. Acquired resistance to itraconazole. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 29:509–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Warris A, Klaassen CH, Meis JF, De Ruiter MT, De Valk HA, Abrahamsen TG, Gaustad P, Verweij PE. 2003. Molecular epidemiology of Aspergillus fumigatus isolates recovered from water, air, and patients shows two clusters of genetically distinct strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4101–4106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rath PM, Buchheidt D, Spiess B, Arfanis E, Buer J, Steinmann J. 2012. First reported case of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus due to the TR/L98H mutation in Germany. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:6060–6061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Peláez T, Gijón P, Bunsow E, Bouza E, Sánchez-Yebra W, Valerio M, Gama B, Cuenca-Estrella M, Mellado E. 2012. Resistance to voriconazole due to a G448S substitution in Aspergillus fumigatus in a patient with cerebral aspergillosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:2531–2534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mortensen KL, Jensen RH, Johansen HK, Skov M, Pressler T, Howard SJ, Leatherbarrow H, Mellado E, Arendrup MC. 2011. Aspergillus species and other molds in respiratory samples from patients with cystic fibrosis: a laboratory-based study with focus on Aspergillus fumigatus azole resistance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49:2243–2251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Burgel PR, Baixench MT, Amsellem M, Audureau E, Chapron J, Kanaan R, Honore I, Dupouy-Camet J, Dusser D, Klaassen CH, Meis JF, Hubert D, Paugam A. 2012. High prevalence of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in adults with cystic fibrosis exposed to itraconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:869–874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mortensen KL, Mellado E, Lass-Florl C, Rodríguez-Tudela JL, Johansen HK, Arendrup MC. 2010. Environmental study of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus and other aspergilli in Austria, Denmark, and Spain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:4545–4549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Escribano P, Recio S, Peláez T, González-Rivera M, Bouza E, Guinea J. 2012. In vitro acquisition of secondary azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus isolates after prolonged exposure to itraconazole: presence of heteroresistant populations. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:174–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Denning DW, Park S, Lass-Florl C, Fraczek MG, Kirwan M, Gore R, Smith J, Bueid A, Moore CB, Bowyer P, Perlin DS. 2011. High-frequency triazole resistance found in nonculturable Aspergillus fumigatus from lungs of patients with chronic fungal disease. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52:1123–1129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]