Abstract

Surgical options for symptomatic pathologies of the long head of the biceps (LHB) include tenotomy and tenodesis. Tenotomy is surgically simple and quick, does not require immobilization, and avoids implant complications. However, it is associated with residual “Popeye” muscle deformity and biceps muscle cramps. Tenodesis avoids Popeye deformity, but it is technically a more difficult operation with a longer rehabilitation period and possible implant complications. The purpose of this report is to describe a novel technique for LHB tenotomy that avoids the Popeye muscle deformity. Before releasing the LHB from its anchor over the superior labrum, this technique consists of making an oblique incision, involving 50% of the tendon, distal to its attachment at the superior labrum. A second standard complete tenotomy incision is made about 1.5 cm medial to the oblique incision. The remaining stump of the LHB at the tendon-labrum junction is resected. The first incision, an oblique incomplete incision, allows the remnant of the LHB to open up and form an “anchor shape” that anchors the LHB at the articular entrance of the bicipital groove, thus decreasing the risk of Popeye deformity.

Shoulder pain and dysfunction can arise as a result of long head of the biceps (LHB) pathologies, which—broadly speaking—can be divided into degenerative, inflammatory, instability, entrapment, and traumatic and sport-related types.1 Operative management for LHB disorders includes synovectomy, tendon debridement, transfer, repair of partial tears, and reconstruction of the damaged pulley (for LHB instability); however, tenotomy and tenodesis are by far the most common surgical choices. LHB tenotomy is relatively simple and quick with a short rehabilitation period that does not involve any immobilization. In addition, it does not carry any risks of implant complications. It is, however, associated in some cases with “Popeye” muscle deformity; prolonged ache or cramps in the belly of the biceps; and arguably, loss of elbow supination strength.2 Tenodesis avoids most of these risks, but it is technically more difficult to perform, it carries the risk of implant complications, and the rehabilitation period is longer, which consists of a period of immobilization for most surgeons. Other than the increased risk of the Popeye deformity with tenotomy, both procedures have similar rates of success with comparable outcome scores and rates of satisfaction.3 We describe a novel technique for arthroscopic LHB tenotomy that avoids the classic Popeye muscle deformity (Tables 1-4).

Table 1.

Key Points

| LHB tenotomy is a technique that provides pain relief, functional improvement, and clinical outcome similar to tenodesis, but it is associated with the Popeye deformity. |

| Our tenotomy technique minimizes the risk of this deformity and biceps muscle cramps. |

Table 2.

Summary of Anchor Shape Tenotomy Technique

| Two incisions are performed in the LHB. |

| The first incision is an oblique incomplete incision that involves 50% of the tendon. |

| The second incision is a complete transverse incision that releases the LHB at the tendon-labrum junction. |

| The first incision (oblique incomplete incision) allows the remnant of the LHB to open up and form an anchor shape that anchors the LHB at the articular entrance of the bicipital groove. |

Table 3.

Risks and Benefits of Anchor Shape Tenotomy Technique

| Benefits | Risk |

|---|---|

| Simple | Remnant of LHB is left in proximal bicipital groove, which—in theory—can still cause symptoms |

| Quick | Possible supination weakness |

| Avoids Popeye sign | |

| Avoids muscle cramps | |

| Avoids implant complications |

Table 4.

Experience With Technique in 12 Patients

| 3 mo of follow-up |

| All 12 patients had good pain relief and restoration of function. |

| None had Popeye deformity. |

| Ultrasound imaging showed the presence of the LHB at the bicipital groove in all but 1 patient. |

Technique

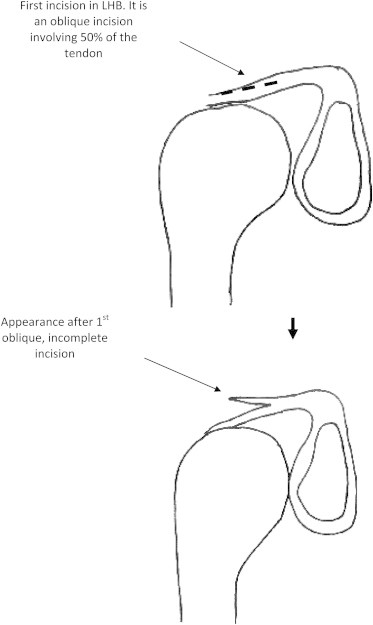

With the patient in either a beach-chair or lateral decubitus position, we introduce the arthroscope through the standard posterior viewing portal to perform a diagnostic arthroscopy. A probe is then introduced through a standard anterior portal. Assessment of the LHB is performed by visualizing the entire length of its intra-articular portion while displacing the tendon inferiorly by the probe (Video 1). When a decision is made to perform tenotomy, this technique involves making 2 incisions in the LHB. The first incision is an oblique incomplete incision that involves 50% of the tendon (Fig 1). By use of arthroscopic scissors, this incision begins approximately 2.5 cm distal to the attachment of the LHB to the labrum complex anchor (just medial to its entrance to the groove) (Video 1). It makes an oblique angle (45°) to the long axis of the LHB, with an incomplete incision involving only 50% of the thickness of the LHB. The incision extends about 1.5 cm in length (Video 1).

Fig 1.

Oblique incomplete incision (first incision).

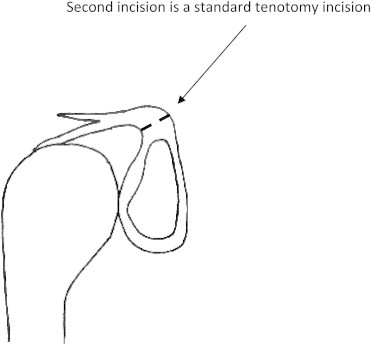

The second incision is a complete transverse incision that releases the LHB at the tendon-labrum junction (Fig 2). This would be the same as a standard LHB tenotomy incision by use of either arthroscopic scissors, arthroscopic basket forceps, or a radiofrequency probe device (Video 1).

Fig 2.

Standard tenotomy incision (second incision).

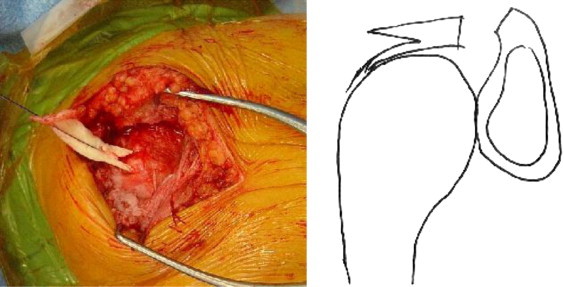

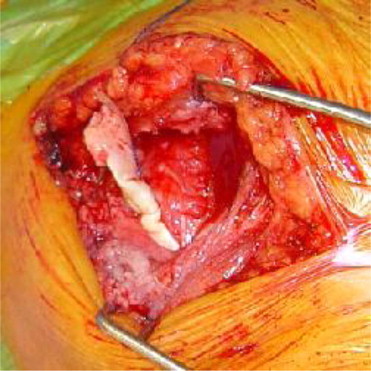

The first incision (oblique incomplete incision) allows the remnant of the LHB to open up and form an “anchor shape” that anchors the LHB at the articular entrance of the bicipital groove (Fig 3). Because this remnant is lodged at the bicipital groove, the risks of distal migration of the tendon and thus a Popeye deformity are reduced (Fig 4, Video 1). To make sure that there is no distal migration, the elbow is then put through the full range of motion while the surgeon visualizes the remnant of the LHB (the anchor shape). The remaining stump at the tendon-labrum junction is debrided with arthroscopic basket forceps or a mechanical shaver. Any coexisting intra-articular pathology is then addressed.

Fig 3.

Photograph and diagram showing appearance after the 2 incisions. (Although the technique is arthroscopic, for clarity, this image was obtained during an open procedure.)

Fig 4.

The remnant of the LHB forms an anchor shape that anchors the LHB at the articular entrance of the bicipital groove. Because this remnant is lodged at the bicipital groove, the risks of distal migration of the tendon and, thus, Popeye deformity are reduced. (Although the technique is arthroscopic, for clarity, the image was obtained during an open procedure.)

We have performed this technique in 12 patients. At 3 months after surgery, all the patients had good pain relief and restoration of function. None had a Popeye deformity. Ultrasound imaging 3 months postoperatively showed the presence of the LHB at the bicipital groove in all but 1 patient.

Postoperative Rehabilitation Protocol

The exact postoperative rehabilitation program is mainly dependent on the type of surgery for any coexisting pathology (e.g., rotator cuff repair). In the absence of a concurrent procedure for any associated pathologies, patients wear a sling for comfort for the first 24 hours, after which they are encouraged to mobilize the shoulder and elbow as pain allows. Active assisted and shoulder and elbow range of motion are initiated immediately without any restrictions.

Discussion

The Popeye deformity and fatigue cramping are recognized complications of LHB tenotomy, with a reported prevalence rate ranging from 3% to 70%.1,3-5 Other than these 2 potential complications with tenotomy, there appears to be little difference in clinical outcome of tenotomy compared with tenodesis.1,3-5 In addition, there is evidence to suggest that there is no difference in elbow flexion strength after the 2 procedures.6 However, whether there is any difference in elbow supination strength with the 2 procedures is open to debate. There are some studies that have reported a decrease of up to 40% in elbow supination strength7 with tenotomy, whereas other investigators have shown no difference with the 2 techniques.6

When faced with the choice of either LHB tenotomy or tenodesis, one has to appreciate that tenotomy is simpler to perform with a quicker rehabilitation period and is devoid of any implant complication risk that may be associated with the Popeye deformity of the biceps muscle. With the exception of this deformity and, arguably, elbow supination strength, there is substantial evidence that there is no difference in clinical outcome scores, pain, strength, and satisfaction between the 2 procedures. Therefore it is logical to suggest that the main advantage of tenodesis is prevention of the Popeye deformity and biceps cramps, and in the presence of a tenotomy technique that avoids this deformity, it would be difficult to argue for tenodesis over tenotomy because the former is a technically more difficult procedure with a more demanding rehabilitation period.

In this report we have presented a technique that has the advantage of reducing the risk of Popeye deformity and biceps muscle cramps. Admittedly, the risk with this technique is that it still leaves a remnant of the LHB in the proximal bicipital groove, which—in theory—could still cause symptoms. However, with our series all patients had good pain relief and restoration of function at 3 months postoperatively.

There are also other reported techniques of tenotomy that have been shown to reduce the risk of distal migration of the tendon, but these involve violation of the labral complex, which our technique avoids.8 LHB tenotomy is a technique that provides pain relief, functional improvement, and clinical outcome similar to tenodesis, but it is associated with the Popeye deformity. The tenotomy technique described in this report minimizes the risk of this deformity and biceps muscle cramps.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge Dr. Arildo Eustáquio Paim of Belo Horizonte, Brazil, from whom we learned this technique.

Footnotes

The authors report that they have no conflicts of interest in the authorship and publication of this article.

Supplementary Data

The anchor shape tenotomy technique is performed arthroscopically.

References

- 1.Ahrens P.M., Boileau P. The long head of biceps and associated tendinopathy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1001–1009. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B8.19278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ejnisman B., Monteiro G.C., Andreoli C.V., de Castro Pochini A. Disorder of the long head of the biceps tendon. Br J Sports Med. 2010;44:347–354. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.064139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frost A., Zafar M.S., Maffulli N. Tenotomy versus tenodesis in the management of pathologic lesions of the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:828–833. doi: 10.1177/0363546508322179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly A.M., Drakos M.C., Fealy S., Taylor S.A., O'Brien S.J. Arthroscopic release of the long head of the biceps tendon: Functional outcome and clinical results. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:208–213. doi: 10.1177/0363546504269555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koh K.H., Ahn J.H., Kim S.M., Yoo J.C. Treatment of biceps tendon lesions in the setting of rotator cuff tears: Prospective cohort study of tenotomy versus tenodesis. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:1584–1590. doi: 10.1177/0363546510364053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elser F., Braun S., Dewing C.B., Giphart J.E., Millett P.J. Anatomy, function, injuries, and treatment of the long head of the biceps brachii tendon. Arthroscopy. 2011;27:581–592. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maynou C., Mehdi N., Cassagnaud X., Audebert S., Mestdagh H. Clinical results of arthroscopic tenotomy of the long head of the biceps brachii in full thickness tears of the rotator cuff without repair: 40 casesRev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2005;91:300–306. doi: 10.1016/s0035-1040(05)84327-2. (in French) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradbury T., Dunn W.R., Kuhn J.E. Preventing the Popeye deformity after release of the long head of the biceps tendon: An alternative technique and biomechanical evaluation. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:1099–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The anchor shape tenotomy technique is performed arthroscopically.