Abstract

Objective

To examine the relationship between functional limitation, socioeconomic inequality, and depression in a diverse cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Methods

The study design was cross-sectional and subjects were from the University of California, San Francisco RA Cohort. Patients were enrolled from 2 rheumatology clinics, an urban county public hospital and a university tertiary care medical center. Age, sex, race/ethnicity, disease activity, functional limitation, and medications were variables collected at clinical visits. The patient’s clinic site was used as a proxy for his or her socioeconomic status. The outcome variable was depressive symptom severity measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire 9. Differences in characteristics between depressed and nondepressed patients were calculated using 2-sided t-tests or the Pearson’s chi-square test. For the multivariate analysis, repeated measures with generalized estimating equations were used.

Results

There were statistically significant differences between depressed and nondepressed patients related to race/ethnicity, public versus tertiary care hospital rheumatology clinic, disability, and medications. In the multivariate analysis, increased functional limitation and public clinic site remained significantly associated with increased depression scores. A significant interaction existed between clinic site and disability. Mean depression scores rose more precipitously as functional limitation increased at the public hospital rheumatology clinic.

Conclusion

There are disparities in both physical and mental health among individuals with low socioeconomic status. The psychological effects of disability vary in patients with RA such that a vulnerable population with functional limitations is at higher risk of developing depressive symptoms.

INTRODUCTION

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic disease that affects 1.3 million Americans (1,2), with many patients developing progressive functional limitation and physical disability (3). Depression is common, occurring in 13– 42% of patients with RA (4 –12), and is associated with worse outcomes. Specifically, patients with RA and subsequent depression have increased health service utilization (13), are less likely to be adherent with their medications (14), and are more likely to discontinue anti–tumor necrosis factor α (anti-TNFα) treatment (15). Comorbid depression is an independent risk factor for incident myocardial infarction (16), suicidal ideation, and death in patients with RA (17–20).

Studies have shown that increased disability, as measured by the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), is associated with depression in patients with RA (11,21–24). While functional limitation is a known contributor to depression in RA, it is also well known that socioeconomic position as measured by race/ethnicity, sex, age, income, education, and health access is a powerful determinant of health in the US (25–28). It is not surprising that patients who experience poverty are more likely to be depressed (29) and have worse health outcomes. Patients with RA and low socioeconomic status (SES) have higher HAQ scores, disease activity, depressive symptoms, and mortality rates (30,31).

Previous studies have focused exclusively on the main effects of either functional limitation or SES on depression in patients with RA, but the studies did not determine whether the association between disability and depression differs across levels of SES. An accurate description of the relationship between depression, functional limitation, and SES is necessary. If such an interaction exists and is ignored, then the effects are imprecise, which leads to biased results. Also, if an interaction is present, then there is a group of vulnerable patients who could benefit from earlier identification and treatment.

We sought to examine the relationship between functional limitations, SES, and depression in a diverse cohort of patients with RA. Our objective was to assess the extent to which low SES influences the relationship between disability and depression in order to better identify those patients at higher risk of depression, which in turn can lead to better treatment and improve health outcomes in depressed patients with RA.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study population

Study subjects were patients from the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) RA Cohort, a multisite observational cohort. Details about enrollment and data collection have been reported previously (32) and are summarized briefly here. Subjects were consecutively enrolled from 2 outpatient rheumatology clinics; one is an urban county public hospital serving a poor population, and the other is a referral tertiary care medical center. Enrollment began in October 2006, and the data were gathered at regular clinical visits. Patients were included in the analysis if they were age 18 years, met the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for RA (33), had at least 1 clinical visit that included an assessment of depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9), had an assessment of disease activity using the RA-specific Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28) performed by a rheumatologist, and had an assessment of disability using the HAQ score. The UCSF Committee on Human Research approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained and patients were interviewed in the language of their choice (English, Cantonese, Mandarin, or Spanish).

Ascertainment of depression

The outcome variable was depressive symptom severity measured by the PHQ-9, which was administered as a written questionnaire during the clinic visit. This self-report depression questionnaire yields a score on a 27-point scale and is used to identify patients at risk of major depressive disorder (34,35). The PHQ-9 is composed of 9 items, which correspond to the 9 diagnostic criteria of major depressive disorder, plus 1 item to assess functional impairment secondary to depression. We chose the PHQ-9 as a measure for depression because it was developed for primary care, is in widespread use for a range of acute and chronic medical conditions, was developed to closely parallel the diagnostic symptoms of major depressive disorder (34 –36), and has established reliability and validity in white, African American, Asian, and Hispanic populations (37,38). Commonly used cutoff scores include 5–9 (mild depressive symptoms), 10 –14 (moderate depressive symptoms), 15–19 (moderate to severe depressive symptoms), and ≥20 (severe depressive symptoms). We dichotomized moderate to severe depressive symptoms as present (PHQ-9 score ≥10) or absent–mild (PHQ-9 score <10) in univariate analyses. The term “depressed” will be used from this point forward to refer to participants meeting this threshold of symptom severity. The PHQ-9 score was used as a continuous variable in the multivariate model.

Assessment of clinical data

Disease activity was assessed with the DAS28, which was calculated at each clinic visit. The DAS28 includes scores of tender and swollen joint counts, patient global disease activity rating scale, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (39,40). With the use of trained translators if necessary, physicians recorded joint counts at each clinic visit. The patient completed the visual analog scale for disease activity before each visit in her or his preferred language (English, Spanish, or Chinese). An ESR, measured according to standard Westergren techniques, was drawn at the end of the clinical encounter. Functional limitation was evaluated with the 20-item HAQ score (41), which is a reliable and valid assessment of functional limitations in RA. The HAQ has been translated and validated in Mandarin/Cantonese (42) and Spanish (43). Disease duration was calculated based on the date of diagnosis recorded in the medical charts. Treatment-related variables included prednisone use and other disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) such as methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine, azathioprine, leflunomide, anti-TNFα medications, or other biologic medications.

Demographic and socioeconomic measures

Age, sex, and self-report race/ethnicity were collected at the baseline clinical visit. The patients’ clinic site (public hospital versus tertiary care medical center) was used as a proxy for their SES. In order to justify using a clinic site as a proxy for SES, we evaluated validated markers of SES (44), including education, household income, health access, and immigrant status, in a subset of patients from both clinic sites who completed a single structured telephone interview between 2007 and 2009 as part of another study.

Data collection

Trained study research staff administered standardized questionnaires (PHQ-9, HAQ) in the clinic setting and structured telephone interviews separately from the clinical encounters; the separate interview was conducted because the length would have proven disruptive to the clinics. All clinical data and standardized questionnaires (i.e., PHQ-9, visual analog scales for DAS, and HAQ) were done in the patient’s preferred language (English, Spanish, or Chinese) with the use of trained interpreters if needed. Telephone interviews were also conducted in the patient’s preferred language. Research staff and treating physicians were blind to PHQ-9 scores and HAQ scores since the scores were tabulated independently. Physicians were blind to questionnaire responses.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics of the patients’ characteristics were reported using a mean ± SD for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. Differences in baseline characteristics between depressed and nondepressed patients were assessed using a 2-sided t-test or the Pearson’s chi-square test. Bivariate associations between socioeconomic measures and clinic sites were calculated using linear regression, Pearson’s chi-square tests, or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were normally distributed except for disease duration, which was skewed toward longer disease.

The multivariate analysis focused on assessing associations of function with depression scores, while accounting for covariates. The unit of analysis was a subject’s clinical visit, in which the patient had a PHQ-9 collected. For this analysis, we used generalized estimating equations (GEEs) with robust SEs that permit the use of multiple observations per person while taking into account within-subject correlations between measurements over time, and to account for the influence of potential confounding covariates. Covariates for multivariable regression included sex, age, HAQ score, clinic site, disease duration, and DMARD and prednisone use. Race/ethnicity was not included as a covariate in the multivariable model because it was colinear with clinic site and because clinic site was considered to be a robust indicator of SES, which was the primary focus of our analysis.

Interpretation of the coefficient using repeated-measures analysis with robust SEs is the same as for linear regression (45). Given the modest-sized data set and the number of predictors, bootstrapping (i.e., a resampling of subjects, not observations) was employed to check the reliability of the SEs and confidence intervals. All analyses were conducted using STATA software, version 10.0 (StataCorp).

RESULTS

Included in the analysis were 824 visits for 466 patients, 223 from the public hospital rheumatology clinic and 243 from the tertiary care rheumatology clinic. The average number of outpatient rheumatology visits per patient was 2 (range 1–5). In this study, 85% of included patients were women, with a mean age of 54 years (Table 1). The mean ± SD HAQ score was 1.2 ± 0.8 and the mean ± SD DAS28 score was 4.0 ± 2.2, which is indicative of fairly high levels of functional impairment and disease activity, respectively. In our cohort, 37% of patients scored ≥10 on the PHQ-9 during at least 1 clinic visit, which corresponded to depression of at least moderate severity.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the University of California, San Francisco rheumatoid arthritis cohort*

| Characteristics | All subjects (n = 466) | PHQ-9 score <10 (n = 294) | PHQ-9 score ≥10 (n = 172) | P† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | 396 (85) | 250 (85) | 146 (85) | 0.87 |

| Age, mean ± SD years | 54.0 ± 14.0 | 54.0 ± 14.0 | 54.0 ± 14.0 | 0.57 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.01 | |||

| Latino/Hispanic | 158 (34) | 91 (31) | 67 (39) | |

| African American | 47 (10) | 26 (9) | 21 (12) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 117 (25) | 73 (25) | 43 (25) | |

| White | 144 (31) | 103 (35) | 41 (24) | |

| Hospital clinic site | 0.03 | |||

| Public | 243 (52) | 147 (50) | 100 (58) | |

| University | 223 (48) | 147 (50) | 72 (42) | |

| Disease duration, mean ± SD years | 11.0 ± 9.0 | 11.0 ± 10.0 | 11.0 ± 9.0 | 0.96 |

| HAQ score, mean ± SD | 1.2 ± 0.83 | 1.1 ± 0.74 | 1.4 ± 0.93 | <0.0001 |

| Antibody positive | ||||

| Rheumatoid factor | 364 (78) | 232 (79) | 132 (77) | 0.63 |

| Anti-CCP | 373 (80) | 235 (80) | 138 (80) | 0.93 |

| Prednisone | 292 (63) | 185 (63) | 107 (62) | 0.85 |

| Prednisone dose, mean ± SD mg | 6.0 ± 4.0 | 6.0 ± 4.0 | 7.0 ± 4.0 | 0.44 |

| DMARDs‡ | 356 (76) | 232 (79) | 124 (72) | 0.02 |

| Anti-TNFα | 122 (26) | 76 (26) | 46 (27) | 0.90 |

Values are the number (percentage) unless otherwise indicated. PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire 9; HAQ = Health Assessment Questionnaire; anti-CCP = anti– cyclic citrullinated peptide; DMARD = disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; anti-TNFα = anti–tumor necrosis factor α.

By 2-sided t-tests or Pearson’s chi-square tests, as appropriate.

Includes any DMARD other than prednisone (i.e., methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine, azathioprine, leflunomide, anti-TNFα medications, and rituximab).

In the univariate analyses of baseline data, there were statistically significant differences between depressed and nondepressed patients related to race/ethnicity (P = 0.01), public versus university hospital rheumatology clinic (P = 0.03), functional limitation (P < 0.0001), and DMARD treatment (P = 0.02) (Table 1). There was no difference in depression symptom severity with regard to sex, age, disease duration, steroid use and dose, or biologic medications. Patients at the county hospital had significantly higher depression scores, with a mean ± SD PHQ-9 score of 7.3 ± 5.8 compared with 5.7 ± 5.3 from patients at the tertiary care medical center (P = 0.001).

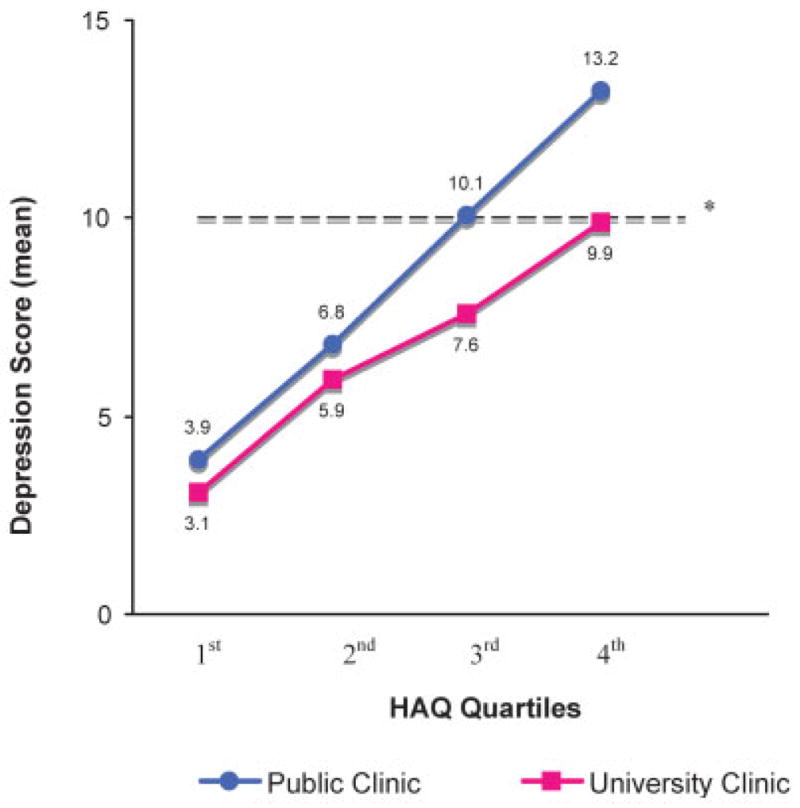

A significant interaction existed between clinic site and HAQ score, such that the association of functional limitation with depression scores was stronger for patients at a public hospital clinic compared with those at a tertiary care center. Mean depression scores rose more precipitously as HAQ quartiles increased at the public hospital rheumatology clinic. The association between disability and depressive symptoms is not constant; the magnitude of the association depends on which rheumatology clinic the patient attends. This is evidenced pictorially by the divergent, nonparallel slopes in Figure 1. In the multivariate analysis (Table 2), increased functional limitation and clinic site remained significantly associated with increased depression scores. When bootstrapping was employed, the confidence intervals from this multivariate model remained similar.

Figure 1.

Depression scores by disability and socioeconomic status (SES). Clinic site as proxy for SES. * = corresponds to ≥moderate depressive symptoms. HAQ = Health Assessment Questionnaire.

Table 2.

Multivariate model of predictors of depression*

| Characteristic | GEE coefficient (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| Men | Reference | |

| Women | −0.13 (−1.4, 1.1) | 0.84 |

| Age, years | −0.02 (−0.05, 0.03) | 0.47 |

| University hospital, HAQ score | ||

| First quartile | Reference | |

| Second quartile | 2.8 (1.7, 3.9) | <0.0001 |

| Third quartile | 4.7 (3.4, 6.0) | <0.0001 |

| Fourth quartile | 9.1 (6.8, 11.3) | <0.0001 |

| Public hospital, HAQ score | ||

| First quartile | 0.99 (−0.08, 2.1) | 0.07 |

| Second quartile | 3.3 (2.1, 4.6) | <0.0001 |

| Third quartile | 7.0 (5.8, 8.3) | <0.0001 |

| Fourth quartile | 11.7 (9.8, 13.7) | <0.0001 |

| Disease duration, years | −0.02 (−0.07, 0.03) | 0.37 |

| DMARD† | ||

| No | Reference | |

| Yes | −0.47 (−1.6, 0.66) | 0.42 |

| Prednisone | −0.39 (−1.3, 0.55) | 0.41 |

GEE = generalized estimating equation; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; HAQ = Health Assessment Questionnaire; DMARD = disease-modifying antirheumatic drug.

Includes any DMARD other than prednisone.

To determine the appropriateness of using clinic site as a proxy for SES, we compared a subset of patients at each site who had provided additional information via a telephone interview (Table 3). Compared with patients at the university clinic, patients at the public hospital clinic have less education, less access to health care, and decreased household income (P = 0.0001). They are more likely to be immigrants (P = 0.0001), women (P = 0.03), and of nonwhite race/ethnicity (P = 0.0001). Along with higher depression scores, patients at the public hospital clinic have higher disease activity scores, higher disability scores, and require more treatment with DMARDs. It appears that clinic site serves as a reliable proxy for socioeconomic position in this sample.

Table 3.

Socioeconomic status characteristics by clinic site (subgroup analysis)*

| Characteristic | Tertiary care clinic (n = 141) | Public hospital clinic (n = 103) | P† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD years | 57 ± 15 | 53 ± 13 | 0.01 |

| Women | 113 (80) | 93 (90) | 0.03 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.0001 | ||

| Latino/Hispanic | 23 (29) | 55 (53) | |

| African American | 10 (7) | 10 (10) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 12 (9) | 37 (36) | |

| White | 87 (62) | 1 (1) | |

| Other | 9 (6) | 0 (0) | |

| Education | 0.0001 | ||

| Less than high school graduate | 14 (10) | 53 (52) | |

| High school graduate/some college | 53 (38) | 40 (40) | |

| College graduate | 71 (50) | 8 (8) | |

| Household income | 0.0001 | ||

| <$20,000 | 22 (17) | 53 (66) | |

| $20,000–$80,000 | 46 (35) | 26 (33) | |

| ≥$80,000 | 63 (48) | 1 (1) | |

| Immigrant | 34 (24) | 85 (85) | 0.0001 |

| Insurance status | 0.0001 | ||

| No insurance | 1 (1) | 15 (15) | |

| Principal source of insurance | 0.0001 | ||

| Employer based | 51 (36) | 3 (4) | |

| Medicare | 67 (48) | 27 (32) | |

| Medicaid | 15 (11) | 35 (41) | |

| Other | 7 (5) | 20 (24) |

Values are the number (percentage) unless otherwise indicated.

Calculated using linear regression, Pearson’s chi-square tests, or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate.

DISCUSSION

Our results concur with previous studies about the prevalence of comorbid depression in RA; 37% of RA patients in our cohort meet criteria for moderate to severe depressive symptoms. As reported previously in the literature, increased HAQ scores and low SES are associated with depressive symptoms in patients with RA (21–24). However, stratifying patients by outpatient clinic site reveals new and important findings.

Without regard to clinic site, there are increases in depression score for each unit increase in the HAQ. Receiving care at the public county clinic is also associated with higher increases in depression scores. However, when patients are stratified by clinic site (Table 2), the change in depression score becomes more meaningful. The tacit assumption that disability and SES have independent consequences on depressive symptoms in patients with RA does not hold. One potential explanation for our results is that at every level of functioning, persons from a lower SES may not have the support and coping skills to perform as well as those from a higher SES, leading to even higher rates of depression. Likely, there are different psychological effects with regard to functional limitations for the immigrant who seeks care at a public hospital clinic compared with the patient who gets treatment at a tertiary care clinic. For example, disability that causes a work disruption for individuals in manual labor jobs, as opposed to white collar, professional jobs, could lead to greater depressive symptom severity.

There are limitations to our study. The design was cross-sectional and therefore causality between greater HAQ scores and the associated, increased depressive symptoms cannot be established. However, a previously conducted longitudinal study (46) showed that the temporal relationship between arthritis and mood disorders, such as depression, is unidirectional and that preexisting arthritis leading to disability elevates the risk of depression and not vice versa. Furthermore, it has also been shown that functional decline precedes the onset of depression (23,24), so while causality cannot be proven in this study, it has been established with prior longitudinal data.

As in other chronic conditions, assessing depressive symptoms in patients with RA can be difficult. It is well understood that somatic symptoms of depression (e.g., fatigue or decreased energy) overlap with symptoms of RA. Consequently, there is a risk that depression in RA may be overestimated (47). Another limitation is that patients seen at the county hospital may represent a sicker population then those referred to the tertiary care center rheumatology clinic. This is likely a reflection of referral practices to a public urban hospital clinic.

Our accessible population, i.e., urban, underserved patients as well as those seen at a university-affiliated clinic, may not be generalizable to all patients with RA. Using clinic site as a proxy for SES may also be a limitation related to generalizability since it reduces the ability for others to replicate results. However, by comparing well-validated measures of SES (race/ethnicity, education, income, health access, and immigrant status) in a subset of patients between the clinic sites, we attempted to measure as much relevant socioeconomic information as possible. By considering how clinic site may measure SES in a thoughtful way and acknowledging its limitations, we believe that it functions as a dependable proxy for SES in this sample.

Poor health outcomes persist in patients with RA and depression despite advances in available treatment. Recognizing the variability in psychological effects in patients with RA, such that a vulnerable population is at higher risk of depression, can help guide treatment to include prevention of functional limitations and subsequent depression in these susceptible patients. For example, patients who receive adequate emotional support report fewer depressive symptoms (48). A treatment program that includes psychological support targeted toward patients with low SES may ameliorate health inequalities in this vulnerable population.

There are disparities in both physical and mental health among individuals with low SES, and the presence of poor physical functioning exacerbates the disparity in mental health. The interaction between functional limitation and low SES in patients with RA suggests that, for the same level of disability, patients with low SES may be more likely to experience depression. Failure to acknowledge this interaction may perpetuate health disparities by ignoring these differences. Detection and documentation of the differing effects of disability on depression between patients of different SES can help rheumatologists move forward to creating solutions and improving health outcomes by initiating treatment for depression.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Arthritis Foundation, the American College of Rheumatology Research and Education Foundation “Within Our Reach” Grant, the Rosalind Russell Medical Research Center for Arthritis, University of California, San Francisco, and the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine Research Evaluation & Allocation Committee.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors approved the final version to be submitted for publication. Dr. Margaretten had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study conception and design. Margaretten, Julian, Katz, Imboden, Yelin.

Acquisition of data. Margaretten, Barton, Tonner, Graf, Imboden, Yelin.

Analysis and interpretation of data. Margaretten, Trupin, Tonner, Yelin.

References

- 1.Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Kwoh CK, et al. for the National Arthritis Data Workgroup. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States: part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:15–25. doi: 10.1002/art.23177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence RC, Helmick CG, Arnett FC, Deyo RA, Felson DT, Giannini EH, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and selected musculoskeletal disorders in the United States. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:778–99. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199805)41:5<778::AID-ART4>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yelin E, Meenan R, Nevitt M, Epstein W. Work disability in rheumatoid arthritis: effects of disease, social, and work factors. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93:551–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-93-4-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hider SL, Tanveer W, Brownfield A, Mattey DL, Packham JC. Depression in RA patients treated with anti-TNF is common and under-recognized in the rheumatology clinic. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:1152–4. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakajima A, Kamitsuji S, Saito A, Tanaka E, Nishimura K, Horikawa N, et al. Disability and patient’s appraisal of general health contribute to depressed mood in rheumatoid arthritis in a large clinical study in Japan. Mod Rheumatol. 2006;16:151–7. doi: 10.1007/s10165-006-0475-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frank RG, Beck NC, Parker JC, Kashani JH, Elliott TR, Haut AE, et al. Depression in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:920–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdel-Nasser AM, Abd El-Azim S, Taal E, El-Badawy SA, Rasker JJ, Valkenburg HA. Depression and depressive symptoms in rheumatoid arthritis patients: an analysis of their occurrence and determinants. Br J Rheumatol. 1998;37:391–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/37.4.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright GE, Parker JC, Smarr KL, Johnson JC, Hewett JE, Walker SE. Age, depressive symptoms, and rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:298–305. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199802)41:2<298::AID-ART14>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pincus T, Griffith J, Pearce S, Isenberg D. Prevalence of self-reported depression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35:879–83. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.9.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dickens C, McGowan L, Clark-Carter D, Creed F. Depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of the literature with meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:52–60. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smedstad LM, Moum T, Vaglum P, Kvien TK. The impact of early rheumatoid arthritis on psychological distress: a comparison between 238 patients with RA and 116 matched controls. Scand J Rheumatol. 1996;25:377–82. doi: 10.3109/03009749609065649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lowe B, Willand L, Eich W, Zipfel S, Ho AD, Herzog W, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity and work disability in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:395–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz PP, Yelin EH. Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms among persons with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:790–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Julian LJ, Yelin E, Yazdany J, Panopalis P, Trupin L, Criswell LA, et al. Depression, medication adherence, and service utilization in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:240–6. doi: 10.1002/art.24236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McNamara D. Depression interferes with anti-TNF therapy. Rheumatol News. 2007;6:1. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scherrer JF, Virgo KS, Zeringue A, Bucholz KK, Jacob T, Johnson RG, et al. Depression increases risk of incident myocardial infarction among Veterans Administration patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31:353–9. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Treharne GJ, Lyons AC, Kitas GD. Suicidal ideation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: research may help identify patients at high risk. BMJ. 2000;321:1290. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuller-Thomson E, Shaked Y. Factors associated with depression and suicidal ideation among individuals with arthritis or rheumatism: findings from a representative community survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:944–50. doi: 10.1002/art.24615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ang DC, Choi H, Kroenke K, Wolfe F. Comorbid depression is an independent risk factor for mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1013–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pincus T. Is mortality increased in patients with rheumatoid arthritis? J Musculoskeletal Med. 1988;5:27–46. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Margaretten M, Yelin E, Imboden J, Graf J, Barton J, Katz P, et al. Predictors of depression in a multiethnic cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1586–91. doi: 10.1002/art.24822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Covic T, Adamson B, Spencer D, Howe G. A biopsychosocial model of pain and depression in rheumatoid arthritis: a 12-month longitudinal study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42:1287–94. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katz PP, Yelin EH. The development of depressive symptoms among women with rheumatoid arthritis: the role of function. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:49–56. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Katz PP, Yelin EH. Activity loss and the onset of depressive symptoms: do some activities matter more than others? Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1194–202. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200105)44:5<1194::AID-ANR203>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Navarro V. Race or class versus race and class: mortality differentials in the United States. Lancet. 1990;336:1238–40. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92846-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lantz PM, House JS, Lepkowski JM, Williams DR, Mero RP, Chen J. Socioeconomic factors, health behaviors, and mortality: results from a nationally representative prospective study of US adults. JAMA. 1998;279:1703–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andrulis DP. Access to care is the centerpiece in the elimination of socioeconomic disparities in health. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:412–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-5-199809010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fiscella K, Franks P, Gold MR, Clancy CM. Inequality in quality: addressing socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic disparities in health care. JAMA. 2000;283:2579–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.19.2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lorant V, Deliege D, Eaton W, Robert A, Philippot P, Ansseau M. Socioeconomic inequalities in depression: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:98–112. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harrison MJ, Tricker KJ, Davies L, Hassell A, Dawes P, Scott DL, et al. The relationship between social deprivation, disease outcome measures, and response to treatment in patients with stable, long-standing rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:2330–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maiden N, Capell HA, Madhok R, Hampson R, Thomson EA. Does social disadvantage contribute to the excess mortality in rheumatoid arthritis patients? Ann Rheum Dis. 1999;58:525–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.58.9.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barton JL, Imboden J, Graf J, Glidden D, Yelin EH, Schillinger D. Patient-physician discordance in assessments of global disease severity in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:857–64. doi: 10.1002/acr.20132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, Linzer M, deGruy FV, III, Hahn SR, et al. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care: the PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA. 1994;272:1749–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang FY, Chung H, Kroenke K, Delucchi KL, Spitzer RL. Using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to measure depression among racially and ethnically diverse primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:547–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wulsin L, Somoza E, Heck J. The feasibility of using the Spanish PHQ-9 to screen for depression in primary care in Honduras. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;4:191–5. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v04n0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prevoo ML, van ’t Hof MA, Kuper HH, van Leeuwen MA, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight–joint counts: development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:44–8. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balsa A, Carmona L, Gonzalez-Alvaro I, Belmonte MA, Tena X, Sanmarti R. Value of Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS28) and DAS28–3 compared to American College of Rheumatology-defined remission in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:40–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fries JF, Spitz PW, Young DY. The dimensions of health outcomes: the Health Assessment Questionnaire, disability and pain scales. J Rheumatol. 1982;9:789–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koh ET, Seow A, Pong LY, Koh WH, Chan L, Howe HS, et al. Cross cultural adaptation and validation of the Chinese Health Assessment Questionnaire for use in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1998;25:1705–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Esteve-Vives J, Batlle-Gualda E, Reig A. Spanish version of the Health Assessment Questionnaire: reliability, validity and transcultural equivalency. Grupo para la Adaptacion del HAQ a la Poblacion Espanola. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:2116–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Chideya S, Marchi KS, Metzler M, et al. Socioeconomic status in health research: one size does not fit all. JAMA. 2005;294:2879–88. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.22.2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vittinghoff E. Regression methods in biostatistics: linear, logistic, survival, and repeated measures models. New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van ’t Land H, Verdurmen J, Ten Have M, van Dorsselaer S, Beekman A, de Graaf R. The association between arthritis and psychiatric disorders; results from a longitudinal population-based study. J Psychosom Res. 2010;68:187–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Estlander AM, Takala EP, Verkasalo M. Assessment of depression in chronic musculoskeletal pain patients. Clin J Pain. 1995;11:194–200. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199509000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Neugebauer A, Katz PP. Impact of social support on valued activity disability and depressive symptoms in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:586–92. doi: 10.1002/art.20532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]