Abstract

According to the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) in poorer countries, 50% of women of reproductive age report that wife hitting or beating is justified. Such high rates may result from structural pressures to adopt such views or to report the perceived socially desirable response. In a survey experiment of 496 ever-married women 18 – 49 years in rural Bangladesh, we compared responses to attitudinal questions that (1) replicated the 2007 Bangladesh DHS wording and portrayed the wife as transgressive for unstated reasons with elaborations depicting her as (2) involuntarily and (3) willfully transgressive. The probabilities of justifying wife hitting or beating were consistently low for unintended transgressions (0.01–0.08). Willful transgressions yielded higher probabilities (0.40–0.70), which resembled those based on the DHS wording (0.38–0.57). Cognitive interviews illustrated that village women held diverse views, which were attributed to social change. Also, ambiguity in the DHS questions may have led some women to interpret them according to perceived gender norms and to give the socially desirable response of justified. Results inform modifications to these DHS questions and identify women for ideational-change interventions.

Keywords: Bangladesh, demographic and health surveys, gender attitudes, intimate partner violence, survey experiment

Intimate partner violence (IPV) refers to psychological, physical, or sexual assault by a current or former spouse or dating partner (Saltzman et al. 1999). Globally, 11% – 71% of women of reproductive age report prior physical IPV (Garcia-Moreno et al. 2006; ICF Macro 2010; Johnson, Ollus, and Nevala 2008). Since 1995, 77 Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) in 52 poorer countries have gathered data on women’s attitudes about physical IPV against wives. The typical questions have asked if a husband is justified in hitting or beating his wife for behaviors that, to varying degrees, are gender transgressive but for which the wife’s motivation is unstated. In response, almost 50% of women have justified such treatment, with this rate varying from 4% to 90% (Yount et al. 2011).

Women’s high and variable rates of justifying IPV have been explained largely on substantive grounds (e.g., Uthman, Lawoko, and Moradi 2009, 2010; Uthman et al. 2009). Scholars have argued that certain forms of patriarchy motivate women to internalize its norms, even if they ostensibly contradict women’s interests (Kandiyoti 1988). Internalization of patriarchy, in theory, is more likely under family systems that (1) ascribe women to be financially dependent and obedient, (2) ascribe men to be providers and enforcers of obedience, and (3) promise benefits to compliant women (Kandiyoti 1988). Women’s exposure to new opportunities and the media, however, is expected to foster new ideas about gender (Kandiyoti 1988; Westoff and Bankole 1999), including those related to a husband’s treatment of his wife.

International research on women’s justification of IPV has ignored the potential for response effects. In wealthier settings, experimental variations in the wording, ordering, and context of the questions have altered the distributions of reported attitudes (e.g., Holleman 1999; Rugg 1941; Schuman and Presser 1977 1996; Tourangeau, Singer, and Presser 2003). Variations in the DHS attitudinal questions about IPV have accounted for considerable variance in women’s responses (Yount et al. 2011).

Social desirability is another source of response bias, which occurs when respondents align their answers to the perceived norm (DeMaio 1984). In this case, women’s tendency to justify IPV may result from a reluctance to report dissenting views. Research in the U.S. does not support this thesis, in that the general tendency to respond in socially desirable ways has correlated poorly with reported beliefs about wife beating (Saunders et al. 1987). Yet, in Bangladesh, women’s high rates of justifying IPV in surveys contradict the unfavorable views that some women have expressed qualitatively (Schuler and Islam 2008). Systematic research, therefore, is needed to understand the structural and survey conditions that may lead women to justify IPV.

This paper reports on findings from a survey experiment in rural Bangladesh that explored three research questions. First, do women under certain forms of patriarchy agree that wife beating is justified for transgressions of women’s gender-normative behavior? Second, do women under patriarchy who hold dissenting views still say they subscribe to the norm that wife beating is justified? Third, do women who are exposed to new opportunities and the media report less patriarchal views about wife beating? Rural Bangladesh is an apt setting for this study, being a patriarchal setting (Kabeer 1988) where over 40% of women report any physical IPV (Koenig et al. 2003; National Institute of Population Research and Training [NIPORT], Mitra and Associates, and Macro International 2009). Using data from 496 women in six villages, we tested response effects to variations in the attitudinal questions about IPV that were used in the 2007 Bangladesh DHS (BDHS). These questions asked whether wife hitting (aaghat) or beating (maardhor) was justified (uchit) for any of five behavioral transgressions, which varied in degree and left the motivation unstated. In cognitive interviews, ambiguity in the motivation evoked ambivalent responses (Schuler, Yount, and Lenzi forthcoming), which informed two elaborations for a survey experiment. One depicted the wife’s transgressions as unintended, and the second depicted them as willful. Experimentally, women rarely justified wife hitting or beating for unintended transgressions, and justified it more often for willful transgressions and transgressions for which the motivation was unspecified. Cognitive interviews illustrated diverse views about wife beating for unintended and willful transgressions and showed that some women gave the perceived socially desirable response of justified to the more ambiguous DHS questions in which the wife’s motivation for transgressing was unspecified. The next section details the theory underlying our experiment.

WOMEN’S JUSTIFICATION OF IPV UNDER CLASSIC PATRIARCHY

We adapted Kandiyoti’s (1988) theory of bargaining with patriarchy to clarify the (1) gendered rights and duties in Bangladeshi marriages supporting IPV, (2) incentives for women to justify or to appear to justify this system, and (3) social changes that may lead women to adopt dissenting views. According to Kandiyoti (1988), different forms of male domination motivate different strategies by women to maximize their security. Classic patriarchy has appeared in some form in the Muslim Middle East, North Africa, and South and East Asia (Kandiyoti 1988). Under classic patriarchy, girls are married at relatively young ages into households that are headed by their husbands’ fathers. The marriage market in rural Bangladesh has followed this pattern (e.g., Alam 2007). Although Muslim women legally can choose their spouse, in practice their fathers or elder brothers often choose (Alam 2007; Baden et al. 1994), and legal guardianship for the woman passes from father to husband (Alam 2007). Under classic patriarchy, a new bride is subordinate to the men and more senior women, and the patrilineage appropriates her labor and offspring. In rural Bangladesh, the division of labor remains gendered, and the expectation is that women work inside while men work outside (Alam 2007; Baden et al. 1994; Chowdhury 2009). This division is relaxing to some extent, but husbands often appropriate the earnings of working wives (Chowdhury 2009). Thus, customarily, a wife exchanges obedience for her husband’s maintenance (e.g., Alam 2007; Kabeer 1988; Yount and Li 2010) and respects his authority to punish disobedience (Yount and Li 2010; Feldman 2010).1 At the extreme, any transgression of patriarchal norms by a wife reflects disobedience, and a husband’s violent response is justifiable punishment (Yount and Li 2010).

The perceived benefits of abiding by the rules of classic patriarchy may motivate women to internalize its norms (Kabeer 1988; Kandiyoti 1988). Two “benefits” of classic patriarchy for women are illustrative. First, marriage confers a sense of personal and social identity as well as social prestige in the village community (samaj) (Alam 2007). Second, a woman’s authority over daughters-in-law displaces the hardships of early marriage (Kandiyoti 1988). These pressures and benefits of classic patriarchy induce compliance (Kabeer 1988), even with the interpretations of a wife’s transgressions as disobedience and a husband’s violence as justifiable punishment (Yount and Li 2009, 2010). Not surprisingly, more than 80% of married women in some Bangladeshi villages have reported that wife beating is right or acceptable (Schuler and Islam 2008).2

The appearance of compliance with prevailing gender norms, however, may be a conscious strategy for some women (Komter 1989). In such cases, a sense of powerlessness to change their condition may lead dissenting women to display agreement with prevailing norms. Some women may even fear the consequences of dissenting, and for this reason, they choose to appear compliant (Schuler et al. 1996). In a survey of attitudes about IPV, such women would give the socially desirable response that wife hitting or beating is justified for transgressions.

Yet, even in a context of historical classic patriarchy, women’s views about gender may be more varied. In rural Bangladesh, structural changes—including increased schooling and access to the media (Asadullah and Chaudhury 2009; Baden et al. 1994; Westoff and Bankole 1999)—have exposed some women to new opportunities and ideas. For instance, rural women 18 – 24 years in 1995 had completed a mean of only 2.3 grades, but by 2005, they had completed 6.7 grades (Asadullah and Chaudhury 2009). As a result, the views of rural women about wives’ transgressions and husbands’ reactions may be more diverse. Many rural women, for example, have opposed wife beating for reasons that they call trivial, and some have condemned it as wholly unjustified (Schuler, Lenzi, and Yount 2011). With this background, we designed a survey experiment to compare women’s reported attitudes about wife hitting or beating for (1) transgressions of gender-normative behavior that have unstated motivations (the DHS questions) and the same transgressions but depicted as (2) unintended and (3) willful.

SETTING

The study sites were six villages in Faridpur, Magura, and Rangpur districts. These villages, although not randomly selected, were not unusual for rural Bangladesh (Bates et al. 2004), being poor and somewhat, but not atypically, conservative. As in most of Bangladesh, the villagers were ethnically and religiously homogeneous, with most self-identifying as Bangladeshi / Bengali and Muslim (96%). Each village had in it or within 2.0 kilometers a school and at least one non-governmental organization (NGO) offering legal advice, microcredit, primary health care, or schooling. At the time of this study, some women (40% in one village, 2% – 5% in the others) were working as vendors or in rice-processing centers or small factories near their villages. By 2008, around 1% to 15% had migrated to Dhaka or district towns to work in garment factories or as cooks for factory workers. A few men from some of the villages had migrated to Dhaka or abroad for work.

SAMPLE AND DATA

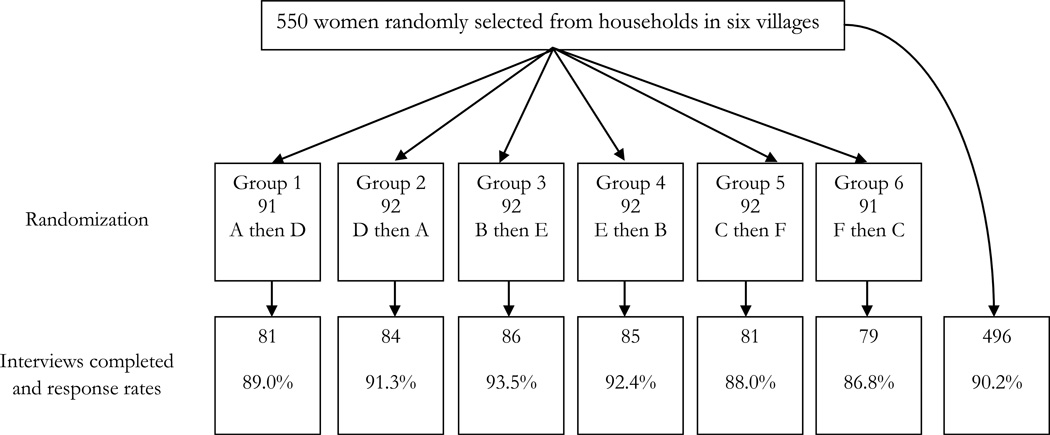

This study was approved by the Emory Institutional Review Board and the Bangladesh Medical Research Council. The main data for this analysis came from the survey, and data from 27 cognitive interviews with different village women guided interpretation of the survey results. Details of the cognitive interviews are described elsewhere (Schuler et al. 2011). The survey sample was drawn from a census of households that was conducted in the study villages from September 15 to December 29 of 2008. This census updated one from 2002, and permitted probability sampling of the survey participants before purposively selecting different participants for the cognitive interviews. In the 2008 census, new household members since 2002 were listed, and prior members who had migrated, died, or were untraceable were recorded as such. Basic demographic data were recorded for all household members, and an approximate one-third subsample of households (n = 550) was selected with probability proportional to the number of eligible women in each village. These women were ever-married, usual residents 18 – 49 years,3 and villages had between 111 and 369 such women. To ensure confidentiality (Kishor and Johnson 2004) and to achieve a representative, self-weighted sample, one eligible woman was selected randomly from each sampled household.4 Each selected woman was randomly assigned to one of six attitudinal modules (Figure 1, Appendix A). Of the 550 selected women, 496 or more than 90% completed interviews, with response rates similar across all six subgroups (87% – 94%, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Experimental design and response rates, overall and by subgroup, ever-married women 18 – 49 years in six villages in Bangladesh

Legend:

Variants of questions eliciting personal attitudes about intimate partner violence against wives

A = standard DHS questions about whether a husband is justified in hitting or beating his wife for any of five behavioral transgressions (goes out without telling him, neglects the children, argues with him, etc…), each with unstated motivations.

B = modified DHS questions about whether a husband is justified in hitting or beating his wife for any of the same five behavioral transgressions in A, but clarifying that the wife’s transgressions were unintended and repeating the question after describing each situation.

C = modified DHS questions about whether a husband is justified in hitting or beating his wife for any of the same five behavioral transgressions in A, but clarifying that the wife’s transgressions were willful and repeating the question after describing each situation.

Variants of questions eliciting personal perceptions of community norms about intimate partner violence against women

D = questions in A but respondents asked to report their perception of what others in their community think about each transgression.

E = questions in B but respondents asked to report their perceptions of what others in their community think about each transgression.

F = questions in C but respondents asked to report their perceptions of what others in their community think about each transgression.

Source: Yount et al. (2012)

All interviews were conducted in private in respondents’ homes by interviewers with extensive prior experience in the study villages. All participants first provided detailed socio-demographic data by answering questions modeled after the 2007 BDHS.5 These data included prior and current residence(s), marital status, literacy, exposure to the media, religion, organizational membership, spousal co-residence, decision-making about household matters, and own and husband’s age, schooling, age at first marriage, work status, and occupation.

Participants then received one of six randomly assigned attitudinal modules, each with two sets of questions. One set pertained to personal attitudes about whether hitting or beating a wife was justified in response to any of five behavioral transgressions, which varied in degree. These transgressions included if the wife: goes out without telling him, neglects the children, argues with him, refuses to have sex with him, and does not obey elders in the family. Variants A of this set of questions followed exactly the wording in the 2007 BDHS, which left the reason for the wife’s transgressions unstated. Variants B of this set depicted the wife’s transgressions as unintended, or arising from extenuating circumstances. Variants C of this set portrayed her transgressions as willful. Variants A, B, and C of this first set of questions each were paired with a second, cognate set of questions (D, E, and F, respectively) pertaining to perceptions of community norms about whether hitting or beating a wife was justified. Question sets within pairs were randomly ordered (A then D; D then A; B then E; E then B; C then F; F then C) to address the possibility that receiving one set first framed responses to the second set. Figure 1 shows the process undertaken to randomize survey participants to these six modules. Appendix A provides the translated questions to which respondents were randomized.

Our analysis focused on differences in the probability of reporting that wife hitting or beating was justified across question variants A, B, and C. Seven binary outcomes were considered. Five captured whether the respondent answered justified (= 1) for each transgression separately. A sixth captured whether the respondent answered justified (= 1) for any of the five transgressions, and a seventh captured whether she answered justified (=1) for all five transgressions. A lack of variation in the seventh outcome for group B limited the multivariate analysis to the first six outcomes.

The main explanatory variable was the variant of the personal attitudes questions to which the respondent was randomized. The experimental group receiving the variant A (DHS) questions, in which all transgressions had unstated motivations, was the referent or control group (= 0). Those receiving the variant B questions, in which all transgressions were depicted as unintended, comprised one treatment group (= 1). Those receiving the variant C questions, in which all transgressions were depicted as willful, comprised the second treatment group (= 2).

Attributes of the respondent, her husband or marriage, and the survey were considered to adjust for observed differences across experimental groups after randomization. The respondent’s covariates included her marital status, religion, age in years, ever attendance of school, completed grades, work in the prior seven days, exposure to the media (newspapers or magazines, radio, and television) at interview, and membership in specific community organizations. Covariates of the husband or marriage included his age in years, residential status, ever schooling, completed grades, and decisions that the respondent made alone. Missing values for the husband’s age (n = 31), completed grades (n = 4), and residential status (n = 30) were imputed with the mean or modal value in the observed sample, and indicator variables for imputation were created. Finally, attributes of the survey included the sub-district (upazila) of the study, random ordering (within experimental groups) of the personal-attitudes versus perceived community-norms questions, and presence of children less than 10 years during the respondent’s interview. The randomization resulted in few observed differences (p ≤ .10) across experimental groups (Table 1). These differences pertained to the respondent’s exposure to print media and spousal schooling. All multivariate analyses adjusted for these variables, imputed spousal schooling, and the ordering of the two sets of attitudinal questions within experimental groups.

Table 1.

Description of the study sample overall and by questionnaire group, ever-married women 18 – 49 years in six villages in Bangladesh

| (n) | DHS-control questions: motivation for transgressions unstated (165) |

DHS-modified questions: transgressions unintentional (171) |

DHS-modified questions: transgressions willful (160) |

Full sample (496) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (s.e.) | Mean | (s.e.) | Mean | (s.e.) | p | Mean | (s.e.) | |

| Respondent's Attributes | |||||||||

| Marital status (married=1) | 95.15 | (0.02) | 89.47 | (0.02) | 96.25 | (0.02) | 93.50 | (0.01) | |

| Religion (Islam=1) | 96.36 | (0.01) | 96.49 | (0.01) | 96.25 | (0.02) | 96.00 | (0.01) | |

| Age in years | 33.84 | (0.72) | 34.11 | (0.71) | 33.79 | (0.73) | 33.92 | (0.41) | |

| Ever attended school (yes=1) | 60.61 | (0.04) | 55.56 | (0.04) | 65.00 | (0.04) | 60.20 | (0.02) | |

| Mean grades completed | 3.35 | (0.27) | 3.09 | (0.27) | 3.90 | (0.30) | 3.44 | (0.16) | |

| Worked outside last 7 days (yes=1) | 40.00 | (0.04) | 41.52 | (0.04) | 39.38 | (0.04) | 40.30 | (0.02) | |

| Reads newspaper/magazine (yes=1) | 6.67 | (0.02) | 8.19 | (0.02) | 11.88 | (0.03) | † | 8.80 | (0.01) |

| Listens to radio (yes=1) | 14.55 | (0.03) | 19.88 | (0.03) | 21.25 | (0.03) | 18.50 | (0.02) | |

| Watches T.V. (yes=1) | 41.82 | (0.04) | 45.03 | (0.04) | 46.25 | (0.04) | 44.30 | (0.02) | |

| Belongs to: | |||||||||

| ASHA (yes=1) | 10.91 | (0.02) | 11.11 | (0.02) | 10.63 | (0.02) | 10.80 | (0.01) | |

| GRAMEEN (yes=1) | 25.45 | (0.03) | 30.41 | (0.04) | 22.50 | (0.03) | 26.20 | (0.02) | |

| BRAC (yes=1) | 14.55 | (0.03) | 9.36 | (0.02) | 10.63 | (0.02) | 11.49 | (0.01) | |

| BRDB (yes=1) | 1.21 | (0.01) | 1.75 | (0.01) | 3.13 | (0.01) | 2.00 | (0.01) | |

| PROSHIKA (yes=1) | 0.61 | (0.01) | 0.00 | (0.00) | 0.00 | (0.00) | 0.20 | (0.00) | |

| Any community organization (yes=1) | 44.85 | (0.04) | 46.20 | (0.04) | 43.75 | (0.04) | 44.96 | (0.02) | |

| Husband's / Partnership Attributes | |||||||||

| Age in years | 43.10 | (0.89) | 42.40 | (0.77) | 42.82 | (0.85) | 42.77 | (0.48) | |

| Age in years imputed (yes=1) | 4.85 | (0.02) | 10.53 | (0.02) | 3.75 | (0.02) | 6.45 | (0.01) | |

| Coresident (yes=1) | 95.15 | (0.02) | 94.15 | (0.02) | 94.38 | (0.02) | 94.556 | (0.01) | |

| Coresidence status missing (yes=1) | 4.85 | (0.02) | 9.94 | (0.02) | 3.75 | (0.02) | 6.25 | (0.01) | |

| Ever attended school (yes=1) | 53.94 | (0.04) | 56.14 | (0.04) | 67.50 | (0.04) | * | 59.00 | (0.02) |

| Mean grades completed | 4.17 | (0.35) | 3.79 | (0.32) | 5.33 | (0.37) | * | 4.41 | (0.20) |

| Completed grades imputed (yes=1) | 0.61 | (0.01) | 0.58 | (0.01) | 1.25 | (0.01) | 0.80 | (0.00) | |

| Wife decides alone about: | |||||||||

| purchases for daily needs (yes=1) | 52.73 | (0.04) | 52.63 | (0.04) | 53.75 | (0.04) | 53.02 | (0.02) | |

| visits to family (yes=1) | 36.36 | (0.04) | 39.18 | (0.04) | 30.00 | (0.04) | 35.28 | (0.02) | |

| healthcare for herself (yes=1) | 27.88 | (0.04) | 28.07 | (0.03) | 25.63 | (0.03) | 27.22 | (0.02) | |

| major household purchases (yes=1) | 14.55 | (0.03) | 18.71 | (0.03) | 14.38 | (0.03) | 15.93 | (0.02) | |

| Other survey-design attributes | |||||||||

| Perceived community norms questions first (yes=1) | 50.91 | (0.04) | 49.71 | (0.04) | 49.38 | (0.04) | 50.00 | (0.02) | |

| Children < 10 years present during interview (yes=1) | 9.70 | (0.02) | 11.11 | (0.02) | 10.00 | (0.02) | 10.28 | (0.30) | |

Notes. 31 (6.2%) missing values for husband's age in years were replaced with the mean husband's age (42.77); 4 (0.8%) missing or unknown values for husband's completed grades were replaced with the mean completed grades within a particular level of schooling; 30 (6.0%) missing values for husband's coresidence status were replaced with a 1.

p ≤ 0.10,

p ≤ 0.05,

p ≤ 0.01,

p ≤ 0.001

METHOD

Univariate analyses were performed to assess the completeness and distributions of all variables. Bivariate analyses were performed to assess the comparability of the treatment and control groups, unadjusted associations of all variables, and potential colinearities among the covariates.

Twelve regressions then were estimated to test the effects of survey treatment with each outcome, unadjusted and adjusted for the above-mentioned covariates. Let i denote respondent, Yi the outcome for respondent i, Ti the treatment or personal attitudes questions to which respondent i was randomized, and Xi a vector of covariates for respondent i. For each outcome, binomial logistic regression was used to model the conditional probability of the outcome, πi = Pr(Yi = 1 | Ti, Xi) as a linear function of treatments and covariates:

| (1) |

where logit(πi) = ln(πi/1− πi). Model diagnostics were performed (Hosmer and Lemeshow 2000), and no multivariate model showed significantly poor fit. From these models, predicted probabilities of justifying wife hitting or beating were estimated for each of the six outcomes and each of the three experimental groups. All probabilities were estimated at the same mean or modal values of the covariates. A descriptive analysis was performed to characterize respondents in the two treatment groups according to a gradient in their reported attitudes about wife hitting or beating. Women were compared who (1) ever justified such treatment for unintended transgressions (no woman reported that wife hitting or beating was always justified for unintended transgressions), (2) always justified it for willful transgressions, (3) sometimes justified it for willful transgressions, (4) never justified it for unintended transgressions, and (5) never justified it for willful transgressions. Women in groups 1 and 2 reported attitudes most reflecting classic patriarchal norms, and women in groups 4 and 5 reported attitudes most contradicting these norms. Women in group 3 reported intermediate attitudes. Because of small sample sizes, differences across groups were discussed qualitatively. Quotes from the cognitive interviews were used to clarify the meanings of women’s survey responses.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Respondents

Almost all women were married (94%) and self-identified as Muslim (96%) (Table 1, full sample). The mean age of women was almost 34 years, and their husbands were nine years older (43 years), on average. A majority of women (60%) and their husbands (59%) had ever attended school, and women had completed on average one grade less than their husbands (3.4 versus 4.4). A large minority (40%) of women had worked outside the house in the prior week. Relatively few (9%) read the print media, but more (19%) listened to the radio, and almost half (44%) watched television. Just under half (45%) of the women belonged to a community organization, and over one quarter (26%) belonged to the Grameen Bank. Almost all women (95%) were living with their husband at the time of the interview. A majority (53%) of women reportedly decided alone about purchases for daily household needs, and substantial minorities reportedly decided alone about health care for themselves (27%) and visits to their friends or relatives (35%). Proportionately fewer (16%) reportedly decided alone about major household purchases.6 The percentage of imputed values for the age, residential status, and completed grades of the husband did not differ across treatment and control groups.

Reported Attitudes about Wife Hitting or Beating

Table 2 displays the percentages of women who justified wife hitting or beating in response to the control (A) and treatment (B, C) variants of the personal attitudes questions, for each of the five transgressions, any of the five, and all five.7 Few women (1% – 8%) justified wife hitting or beating when a transgression was depicted as unintended, and no women justified such treatment for all five unintended transgressions. Relatively more women (38% – 68%) justified such treatment when a transgression was depicted as willful, especially disobeying elders in the marital family (68%), neglecting the children (65%), and arguing with the husband (59%). In fact, a large majority (79%) of women justified wife hitting or beating for at least one willful transgression, and almost one third justified such treatment for all five willful transgressions. The rates of justifying wife hitting or beating for women in the DHS-control group were intermediate (37% – 57%) to those for women in the two treatment groups but most resembled those for women in the willful transgression group.

Table 2.

Percent distribution of responses to individual attitudes questions about wife hitting or beating, by treatment and control groups and type of transgression, ever-married women 18 – 49 years in six villages in Bangladesh

| (n ) | DHS-control questions: motivation for transgressions unstated (165) |

DHS-modified questions: transgressions unintentional (171) |

DHS-modified question: transgressions willful (160) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transgression 1: Goes out without telling him? | ||||

| Yes | 46.06 | 8.18 | 48.13 | *** |

| No | 53.94 | 91.82 | 51.87 | *** |

| Transgression 2: Neglects the children? | ||||

| Yes | 44.24 | 2.34 | 65.00 | *** |

| No | 55.76 | 97.66 | 35.00 | *** |

| Transgression 3: Argues with him? | ||||

| Yes | 49.69 | 0.58 | 59.38 | *** |

| No | 50.31 | 99.42 | 40.62 | *** |

| Transgression 4: Refuses to have sex with him? | ||||

| Yes | 36.96 | 0.58 | 37.50 | *** |

| No | 63.04 | 99.42 | 62.50 | *** |

| Transgression 5: Does not obey elders? | ||||

| Yes | 56.96 | 1.17 | 68.13 | *** |

| No | 43.04 | 98.83 | 31.87 | *** |

| Any transgression? | ||||

| Yes (for any transgression) | 67.27 | 9.36 | 79.38 | *** |

| No | 33.33 | 90.64 | 20.62 | *** |

| All transgressions? | ||||

| Yes (for all transgressions) | 27.87 | 0.00 | 31.25 | *** |

| No | 72.13 | 100.00 | 68.75 | *** |

Notes. DHS = Demographic and Health Survey.

p ≤ 0.10,

p ≤ 0.05,

p ≤ 0.01,

p ≤ 0.001

Multivariate Results

Table 3 shows the unadjusted and adjusted log odds and odds, for each treatment group relative to the control group, of justifying wife hitting or beating for each of the five transgressions and for any of the five. The unadjusted and adjusted relative odds were very similar, so only the latter are discussed. Across all five transgressions, the odds of justifying wife hitting or beating were 90% - 99% lower for women who received the unintended transgression variants than for women who received the DHS-control questions. For two transgressions (goes out without telling him and refuses to have sex with him), women who received the willful transgression variants had similar odds of justifying wife hitting or beating to women who received the DHS-control questions. For the three other transgressions (neglects the children, argues with him, does not obey elders), women receiving the willful transgression variants had 1.6 to 2.4 times higher odds of justifying wife hitting or beating than women receiving the DHS-control questions.

Table 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted log odds and odds of giving an affirmative response to the individual attitude question about intimate partner violence against women, n = 496 respondents randomly assigned to the DHS-control question or one of two DHS-modified questions, ever-married women 18 – 49 years in six villages in Bangladesh

| Outcome | Unadjusted |

Adjusted |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | β | p | OR | p>χ2 | β | p | OR | p>χ2 |

| Transgression 1: Goes out without telling him? | ||||||||

| Experimental group (ref: DHS-control ) | ||||||||

| DHS-modified - wife unintentionally transgresses | −2.26 | 0.00 | 0.10 | −2.30 | 0.00 | 0.10 | ||

| DHS-modified - wife willfully transgresses | 0.08 | 0.71 | 1.09 | 0.13 | 0.55 | 1.14 | ||

| HL Goodness-of-fit Test | 1.00 | 0.94 | ||||||

| Transgression 2: Neglects the children? | ||||||||

| Experimental group (ref: DHS-control ) | ||||||||

| DHS-modified - wife unintentionally transgresses | −3.50 | 0.00 | 0.03 | −3.50 | 0.00 | 0.03 | ||

| DHS-modified - wife willfully transgresses | 0.85 | 0.00 | 2.34 | 0.89 | 0.00 | 2.44 | ||

| HL Goodness-of-fit Test | 1.00 | 0.83 | ||||||

| Transgression 3: Argues with him? | ||||||||

| Experimental group (ref: DHS-control ) | ||||||||

| DHS-modified - wife unintentionally transgresses | −5.12 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −5.14 | 0.00 | 0.01 | ||

| DHS-modified - wife willfully transgresses | 0.39 | 0.08 | 1.48 | 0.47 | 0.04 | 1.60 | ||

| HL Goodness-of-fit Test | 1.00 | 0.76 | ||||||

| Transgression 4: Refuses to have sex with him? | ||||||||

| Experiment group (ref: DHS-control ) | ||||||||

| DHS-modified - wife unintentionally transgresses | −4.60 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −4.64 | 0.00 | 0.01 | ||

| DHS-modified - wife willfully transgresses | 0.02 | 0.92 | 1.02 | 0.11 | 0.64 | 1.12 | ||

| HL Goodness-of-fit Test | 1.00 | 0.48 | ||||||

| Transgression 5: Does not obey elders? | ||||||||

| Experiment group (ref: DHS-control ) | ||||||||

| DHS-modified - wife unintentionally transgresses | −4.72 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −4.80 | 0.00 | 0.01 | ||

| DHS-modified - wife willfully transgresses | 0.48 | 0.04 | 1.61 | 0.55 | 0.02 | 1.73 | ||

| HL Goodness-of-fit Test | 1.00 | 0.92 | ||||||

| Any of the five Transgressions? | ||||||||

| Survey experiment (ref: DHS-control) | ||||||||

| DHS-modified - wife unintentionally transgresses | −2.99 | 0.00 | 0.05 | −3.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 | ||

| DHS-modified - wife willfully transgresses | 0.63 | 0.02 | 1.87 | 0.65 | 0.01 | 1.92 | ||

| HL Goodness-of-fit Test | 1.00 | 0.78 | ||||||

Notes. DHS=Demographic and Health Survey. HL=Hosmer and Lemeshow. Adjusted models control for reading a newspaper or magazine, husband's completed grades of schooling, whether husband's schooling was imputed, and order of individual attitudes versus perceptions of community norms questions.

p ≤ 0.10,

p ≤ 0.05,

p ≤ 0.01,

p ≤ 0.001

Table 4 shows the predicted probabilities and confidence intervals of justifying wife hitting or beating for women who received the DHS-control questions, unintended transgression variants, and willful transgression variants. Overall, the probability justifying wife hitting or beating was sensitive to the portrayed motivation for the transgression. Several specific points warrant comment. First, depicting the wife’s transgressions as unintended yielded consistently low probabilities of justifying wife hitting or beating (0.01 – 0.08). In other words, the particular transgression mattered little in the context of extenuating circumstances. Still, there was a non-negligible (0.09) probability of justifying wife hitting or beating for at least one unintended transgression. Second, depicting the wife’s transgressions as willful yielded a high probability (0.80) of ever justifying wife hitting or beating. This probability varied across transgressions, however, from a high of 0.70 for willfully disobeying elders to a low of 0.40 for willfully refusing sex. Thus, the particular transgression mattered considerably when the wife’s behavior was depicted as intentional. Third, the probabilities of justifying wife hitting or beating for the DHS control questions (0.38 – 0.57) were much closer to those for the willful transgression variants (0.40 – 0.70) than to those for the unintentional transgression variants (0.01 – 0.08). For two transgressions (goes out without telling and refusing sex), the predicted confidence intervals for the DHS questions and willful variants were almost fully overlapping.

Table 4.

Predicted probabilities (and 95% confidence intervals) of giving an affirmative response to the individual attitude question about intimate partner violence against women, n = 496 respondents randomly assigned to the DHS-control question or to one of two DHS-modified questions, ever-married women 18 – 49 years in six villages in Bangladesh

| Outcome | Probability [95% CI] of responding yes, justified |

|---|---|

| Transgression 1: Goes out without telling him? | |

| DHS-control | 0.47 [0.39, 0.55] |

| DHS-modified - wife unintentionally transgresses | 0.08 [0.05, 0.14] |

| DHS-modified - wife willfully transgresses | 0.50 [0.42, 0.58] |

| Transgression 2: Neglects the children? | |

| DHS-control | 0.45 [0.37, 0.53] |

| DHS-modified - wife unintentionally transgresses | 0.02 [0.01, 0.06] |

| DHS-modified - wife willfully transgresses | 0.67 [0.59, 0.74] |

| Transgression 3: Argues with him? | |

| DHS-control | 0.51 [0.44, 0.59] |

| DHS-modified - wife unintentionally transgresses | 0.01 [0.00, 0.04] |

| DHS-modified - wife willfully transgresses | 0.63 [0.55, 0.70] |

| Transgression 4: Refuses to have sex with him? | |

| DHS-control | 0.38 [0.30, 0.46] |

| DHS-modified - wife unintentionally transgresses | 0.01 [0.00, 0.04] |

| DHS-modified - wife willfully transgresses | 0.40 [0.33, 0.49] |

| Transgression 5: Does not obey elders? | |

| DHS-control | 0.57 [0.50, 0.65] |

| DHS-modified - wife unintentionally transgresses | 0.01 [0.00, 0.05] |

| DHS-modified - wife willfully transgresses | 0.70 [0.62, 0.77] |

| Any of the five Transgressions? | |

| DHS-control | 0.67 [0.60, 0.74] |

| DHS-modified - wife unintentionally transgresses | 0.09 [0.06, 0.15] |

| DHS-modified - wife willfully transgresses | 0.80 [0.73, 0.86] |

Notes. DHS=Demographic and Health Survey. HL=Hosmer-Lemeshow.

CI=Confidence Interval

Probabilities are estimated for married women who do not read newspapers or magazines, whose husbands had 4.4 completed grades of schooling, who had no imputed value for husband's completed grades of schooling, who did not have children present during the interview, and who did not receive the question on perceptions of community norms first.

p ≤ 0.10,

p ≤ 0.05,

p ≤ 0.01,

p ≤ 0.001

Interpretations of the Experimental Findings

Social desirability bias may partly explain similarities in the response patterns for the DHS- control questions and willful transgression variants. In separate cognitive interviews of the DHS-questions, some women masked their dissenting views about wife beating because they did not perceive alternatives to their circumstances. One such woman asked the interviewer rhetorically: “What should I tell you about my own opinions? If I make a mistake and my husband beats me, can I do anything about that?” (ID 302902, late 30s, illiterate). When asked if a husband was right to beat his wife, another woman replied “Yes, that is the way is it…Our society has set it up like this…” Yet, after the probe, “I understand that the society has set it up like this, but what is your opinion…?” the woman answered “No, it is not right” (ID 301302, 40 years old, 4 grades).

Still, large differences in the propensities to justify wife hitting or beating for explicitly unintended and willful transgressions suggested real diversity in women’s views, begging the question of who reported which attitudes. Table 5 presents attributes of the five groups of women who: (1) ever justified wife hitting or beating for unintended transgressions (n = 16), (2) always justified it for willful transgressions (n = 50), (3) sometimes justified it for willful transgressions (n = 77), (4) never justified it for unintended transgressions (n = 155), and (5) never justified it for willful transgressions (n = 33).

Table 5.

Attributes of women who always, ever, or never justified wife hitting or beating for a wife's unintended/willful transgressions, ever-married women 18 – 49 years in six villages in Bangladesh

| Group 1 (n = 16) Justified wife hitting or beating for any unintended transgressions? |

Group 2 (n = 50) Justified wife hitting or beating for all 5 willful transgressions |

Group 3 (n = 77) Justified wife hitting or beating for 1–4 willful transgressions? |

Group 4 (n = 155) Never justified wife hitting or beating for any unintended transgressions? |

Group 5 (n = 33) Never justified wife hitting or beating for any willful transgression? |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent's Attributes | Mean | (s.e.) | Mean | (s.e.) | Mean | (s.e.) | Mean | (s.e.) | Mean | (s.e.) |

| Marital status (married=1) | 81.25 | (0.10) | 98.00 | (0.02) | 96.10 | (0.02) | 90.32 | (0.02) | 93.94 | (0.04) |

| Religion (Islam=1) | 100.00 | (0.00) | 94.00 | (0.03) | 98.70 | (0.01) | 96.13 | (0.02) | 93.94 | (0.04) |

| Age in years | 36.44 | (2.72) | 35.66 | (1.34) | 32.25 | (1.01) | 33.86 | (0.73) | 34.58 | (1.65) |

| Ever attended school (yes=1) | 37.50 | (0.13) | 56.00 | (0.07) | 68.83 | (0.05) | 57.42 | (0.04) | 69.70 | (0.08) |

| Mean grades completed | 1.50 | (0.56) | 3.02 | (0.50) | 4.53 | (0.47) | 3.25 | (0.29) | 3.76 | (0.61) |

| Worked outside last 7 days (yes=1) | 25.00 | (0.11) | 40.00 | (0.07) | 37.66 | (0.06) | 43.23 | (0.04) | 42.42 | (0.09) |

| Reads newspaper/magazine (yes=1) | 6.25 | (0.06) | 6.00 | (0.03) | 14.29 | (0.04) | 8.39 | (0.02) | 15.15 | (0.06) |

| Listens to radio (yes=1) | 0.00 | (0.00) | 2.00 | (0.06) | 19.48 | (0.05) | 21.94 | (0.03) | 27.27 | (0.08) |

| Watches T.V. (yes=1) | 31.25 | (0.12) | 46.00 | (0.07) | 45.45 | (0.06) | 46.45 | (0.04) | 48.48 | (0.09) |

| Belongs to: | ||||||||||

| ASHA (yes=1) | 6.25 | (0.06) | 8.00 | (0.04) | 11.69 | (0.04) | 11.61 | (0.03) | 12.12 | (0.06) |

| GRAMEEN (yes=1) | 6.25 | (0.06) | 34.00 | (0.07) | 15.58 | (0.04) | 32.90 | (0.04) | 21.21 | (0.07) |

| BRAC (yes=1) | 12.50 | (0.09) | 8.00 | (0.04) | 12.99 | (0.04) | 9.03 | (0.02) | 9.09 | (0.05) |

| BRDB (yes=1) | 0.00 | (0.00) | 4.00 | (0.03) | 3.90 | (0.02) | 1.94 | (0.01) | 0.00 | (0.00) |

| PROSHIKA (yes=1) | 0.00 | (0.00) | 0.00 | (0.00) | 0.00 | (0.00) | 0.00 | (0.00) | 0.00 | (0.00) |

| Any community organization (yes=1) | 25.00 | (0.11) | 50.00 | (0.07) | 40.26 | (0.06) | 48.39 | (0.04) | 42.42 | (0.09) |

| Husband's / Partner Attributes | ||||||||||

| Age in years | 43.56 | (2.60) | 45.10 | (1.52) | 41.06 | (1.17) | 42.28 | (0.81) | 43.45 | (2.02) |

| Coresident (yes=1) | 100.00 | (0.00) | 94.00 | (0.03) | 92.21 | (0.03) | 93.55 | (0.02) | 100.00 | (0.00) |

| Ever attended school (yes=1) | 68.75 | (0.12) | 64.00 | (0.07) | 72.73 | (0.05) | 54.84 | (0.04) | 60.61 | (0.09) |

| Mean grades completed | 4.06 | (0.91) | 4.66 | (0.63) | 5.69 | (0.53) | 3.76 | (0.35) | 5.52 | (0.93) |

| Wife decides alone about: | ||||||||||

| purchases for daily needs (yes=1) | 25.00 | (0.11) | 58.00 | (0.07) | 53.25 | (0.06) | 55.48 | (0.04) | 48.48 | (0.09) |

| visits to family (yes=1) | 31.25 | (0.12) | 26.00 | (0.06) | 33.77 | (0.05) | 40.00 | (0.04) | 27.27 | (0.08) |

| healthcare for herself (yes=1) | 31.25 | (0.12) | 30.00 | (0.07) | 23.38 | (0.05) | 27.74 | (0.04) | 24.24 | (0.08) |

| major household purchases (yes=1) | 18.75 | (0.10) | 8.00 | (0.04) | 16.88 | (0.04) | 18.71 | (0.03) | 18.18 | (0.07) |

Notes. 31 (6.2%) missing values for husband's age in years were replaced with the mean husband's age (42.77); 4 (0.8%) missing or unknown values for husband’s completed grades were replaced with the mean completed grades within a particular level of schooling; 30 (6.0%) missing values for husband's coresidence status were replaced with a 1.

Consistent with Kandiyoti’s (1988) theory of bargaining with patriarchy, the women whose reported attitudes most reflected classic patriarchal norms (group 1) had fewer opportunities and exposures than did the women whose reported attitudes most contradicted these norms (group 5). Qualitatively, the former group was older on average (36.4 versus 34.6 years), less often had any schooling (38% versus 70%), had fewer mean grades (1.5 versus 3.8), less often had worked outside in the last 7 days (25% versus 42%), less often had exposure to the media (e.g., 0% versus 27% listened to the radio), less often belonged to a community organization (25% versus 42%), had husbands with fewer mean grades (4.0 versus 5.5), and less often made decisions alone about daily purchases (25% versus 48%). Similar differences were apparent across women who ever versus never justified wife hitting or beating for unintended transgressions (groups 1 and 4, respectively) and always versus never justified it for willful transgression (groups 2 and 5, respectively). Women who sometimes justified such treatment for willful transgressions were a mixed group, being the youngest (32.2 years) and most schooled (4.5 grades) but intermediately exposed to work outside (38%) and the media (19% listening to the radio). A clear dose-response relationship was apparent between the extent of women’s exposure to the media (e.g., 0%, 2%, 19%, 22%, 27% listened to the radio) and the extent of their dissent with wife hitting or beating.

Quotes from separate cognitive interviews corroborated the two findings that (1) women in these villages held diverse views about wife beating and (2) social change was a perceived reason for this diversity. Consistent with the survey findings, some women expressed views akin to classic patriarchal norms. According to one woman, “every woman should possess an inner fear that if she does something wrong then her husband would beat her, so that she chooses to live in such a way that she avoids beating” (ID 605902, 30 years old, 2 grades). Others expressed personal ambivalence about wife beating. One such woman stated that: “…in one sense he is justified in beating the wife, while in another sense, he is not.” (ID 512002, 35 years old, no schooling). Still others wholly condemned wife beating, describing the perpetrators as “evil,” “ignorant,” “without consciences,” and “lacking in humanity” (full results available on request). One such woman even questioned the interpretation of a wife’s behavior as transgressive: “Nobody likes it when a few women get together to talk… everyone thinks the only purpose of a woman’s life is to cook” (ID 606402, 43 years old, 12 grades of schooling). Such views, according to one interviewee, signaled a change from “outdated” ideas: “the modern generation thinks it is not justified for a husband to beat his wife under any circumstance. People who stick with outdated ideas…would say that beating is…justified” (ID 602602, 39 years old, 9 grades of schooling).

DISCUSSION

This analysis has examined the structural and survey conditions that may influence women’s tendency to justify wife hitting or beating. Such research is especially needed in poor countries, where 77 DHS across 52 such countries have documented high rates of justification but where the potential influences of survey design are unstudied. To examine these issues, we collected novel data in a survey experiment of women in rural Bangladesh and explored variations in the probabilities of justifying wife hitting or beating for five actions that, to varying degrees, transgressed gender norms and for which the motivation was unstated (as in the DHS questions), unintended, or willful. Our experiment explored three specific ideas. First, women under classic patriarchy may internalize its norms and report that wife hitting or beating is justified, even for unintended transgressions. Second, women with views that contradict these norms may still report that wife hitting or beating is justified to appear compliant in the absence of alternatives. Third, women’s differential exposure to new opportunities and the media may be associated with diverse views about wife hitting or beating.

According to our findings, 9% of the women who received the unintended transgression variants justified wife hitting or beating at least once. Also, 31% of the women who received the willful transgression variants always justified such treatment. These reported attitudes most resembled classic patriarchal norms, which label a wife as disobedient and her husband’s violence as justifiable punishment when the wife’s actions are inconsistent with gender norms. Quotes from the cognitive interviews illustrated how some women internalized these norms. As one woman put it, “[A] husband beats the wife because of her faults and mistakes…This he does rightly.”(ID 300702, 19 years old, 7 grades of schooling). Typically, these women were less schooled, reported less power in decisions, less often were members of community organizations, and had less exposure to certain forms of media. Thus, in keeping with Kandiyoti’s (1988) theory of bargaining with patriarchy, rural women with fewer opportunities and living under classic patriarchy may tend to adhere to its norms.

That said, at least some women who received the DHS questions may have responded that wife hitting or beating was justified to appear compliant with perceived norms. Specifically, the probabilities of justifying such treatment for the DHS-control questions (0.38 – 0.57) were much closer to those for the willful transgression variants (0.40 – 0.70) than to those for the unintentional transgression variants (0.01 – 0.08). In fact, for two transgressions (goes out without telling him and refuses to have sex with him), the predicted confidence intervals for responding justified to the DHS questions and willful transgression variants were almost fully overlapping. Such similarities may have arisen because the DHS questions did not state the wife’s motivation for transgressing, leading some women to interpret the questions according to perceived norms. In cognitive interviews, frequent ambivalence and inconsistencies in women’s responses to the DHS questions strongly supported this interpretation (Schuler et al. forthcoming). Also, some dissenting women may have given the perceived socially desirable response of justified because they did not see a purpose for stating their personal opinion. Cognitive interviews with some village women also corroborated this interpretation (Schuler et al. 2011). Although the precise extent of social desirability bias cannot be estimated, this study provides evidence of its presence in responses to the DHS questions.

Still, diverse views about wife hitting or beating also were evident. Most women (91%), for example, never justified wife hitting or beating for transgressions that were clearly depicted as unintended. In other words, the type or degree of the transgression mattered little when extenuating circumstances were clarified. According to cognitive interviews in these villages, some women felt that the actions of hard-working wives usually were reasonable but were misjudged by others (Schuler et al. forthcoming). According to one woman, “…a woman doesn’t go outside of her house for fun. She only goes outside when it is very urgent…That’s why it wouldn’t be right for her husband to beat her, but [m]ost people would think that she went out without asking her husband’s permission, so her husband did the right thing by beating her” (ID 308002, 29 years, 5 grades of schooling). Thus, the unintended transgression variants developed for this experiment tapped a salient view among village women that most wives are hard working and should not be punished for extenuating circumstances.

Moreover, the probabilities of justifying wife hitting or beating for willful transgressions varied considerably, from 0.40 for refusing sex to 0.70 for disobeying marital elders. This variation suggests that the particular transgression mattered, even for willful acts of disobedience. Disobeying elders is a public act, which shames the wife, her husband, and his parents. In such cases, husbands may feel pressured to regain personal and family honor by “disciplining” such acts through corporal punishment. In contrast, refusing sex is a private act, which can be hidden from public shame and which wives in this context may commit willfully very rarely, out of fear that such acts may provoke the husband to infidelity or even abandonment.

These cross-sectional findings suggest that changes in rural women’s lives have spurred them to adopt new attitudes about gender. Indeed, those women who received the willful transgression variants were as or more likely to not justify than to justify wife hitting or beating for refusing sex (0.60) and for going out without telling the husband (0.50). Also, a majority (69%) of these 160 women reported that wife hitting or beating was not justified for at least one willful transgression, and 21% never justified it for any willful transgression. As expected, the latter women had more schooling, more media exposure, and more schooled husbands than did the women whose attitudes most reflected patriarchal norms (Table 5). Consistent with Thornton’s (2001) model of developmental idealism, some women attributed the condemnation of wife beating to a “modern” generation that had abandoned “outdated ideas.”

Our findings offer guidance for the modification of structured attitudinal questions pertaining to a husband’s treatment of his wife. In general, researchers wishing to explore such attitudes might use questions that (1) clarify the wife’s motivation for her behavior, and (2) expand the list of her behaviors to include more minor (preparing meals late) transgressions, more severe perceived infractions such as infertility or infidelity, and even behaviors that most locals would not see as transgressions in the social context. Clarifying the perceived contexts and meanings of the wife’s behavior in these ways would help to eliminate ambiguities in the question that may lead ambivalent respondents to give what they perceive to be a socially desirable response. Both revisions also would help to distribute women along a more refined attitudinal continuum from always justifying wife hitting or beating for minor, unintended (or even non-) transgressions of gender norms to never justifying it even for major, willful transgressions. Such changes also would help to track more precisely changes in attitudes about IPV over time.

Our findings also generate new questions for research. First, how generalizable are these findings beyond our study villages? Answering this question would require comparative survey experiments that test similar variations to these questions in other contexts. Second, to what extent are men’s responses to these attitudinal questions dependent on clarifying the wife’s motivation for transgressing gender norms? Answering this question would require similar survey experiments in comparative samples of women and men. Third, are the current DHS attitudinal questions capturing the most salient transgressive behaviors of a wife? Answers to this question would require formative research about the various ways in which a wife might “misbehave” and the perceived gravity of these behaviors. This information then could be tested in experimental research in which the list of transgressive behaviors was systematically altered. Finally, further experiments might be useful to quantify response effects among women and men to other alterations in question wording. Such experiments, for example, might test the effects of using different terms to connote a husband’s violence (hit, beat, or both) or women’s attitudes about it (is it justified, right, or normal?) (Schuler et al. 2011). Such research could clarify the meanings of reported attitudes about IPV in the many settings where the DHS have documented more favorable attitudes in women than men (e.g., Uthman et al. 2010).

Finally, our results offer insights about potential mechanisms for ideational change among women in rural Bangladesh and similar settings. In the shorter term, these mechanisms may include exposure to new media, work outside the home, and membership in NGOs that promote women’s legal rights and provide avenues to attain them. Longer term mechanisms may include further gains in women’s and their spouses’ schooling (Table 5) and perhaps improved economic opportunities for husbands. Experiments to assess the attitudinal impacts of “structural” and “ideational” interventions with women and men could clarify what causes them to stop justifying IPV against women.

Acknowledgements

The authors appear in the order of their contributions to this paper. This study was funded by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (1R21HD058173-01/02). The manuscript was first drafted while Dr. Nafisa Halim was a post-doctoral fellow in the Hubert Department of Global Health at Emory University and while Dr. Sidney Ruth Schuler was on staff at the Academy for Educational Development. The comments from anonymous reviewers on a previous version of this paper are greatly appreciated, as are the comments from participants in a seminar on January 18, 2011 at the Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, where these findings were presented. Assistance from Ms. Rachel Lenzi and Ms. Francine Pope in the preparation of this manuscript for submission also is appreciated. All remaining errors are the responsibility of the authors, and the statements and conclusions herein do not necessarily reflect those of Emory University, FHI360, or the funding agency.

Appendix (First appears in Yount et al. 2012)

Questions on personal attitudes about wife hitting or beating

Control Set A: DHS questions

I will now ask you some questions. Please listen to them and then answer thoughtfully. Please tell me what you think.

Sometimes a husband is annoyed or angered by things that his wife does. In your opinion, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife in the following situations

- If she goes out without telling him?

- 1a. If you had to choose, in your opinion, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife if she goes out without telling him?

- If she neglects the children?

- 2a. If you had to choose, in your opinion, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife if she neglects the children?

- If she argues with him?

- 3a. If you had to choose, in your opinion, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife if she argues with him?

- If she refuses to have sex with him?

- 4a. If you had to choose, in your opinion, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife if she refuses to have sex with him?

- If she does not obey elders in the family?

- 5a. If you had to choose, in your opinion, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife if she does not obey elders in the family?

Variant Set B: wife unintentionally transgresses gender norms

I will now ask you some questions. Please listen to them and then answer thoughtfully. Please tell me what you think.

Sometimes a husband is annoyed or angered by things that his wife does. In your opinion, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife in the following situations:

A wife is home alone; at this time someone comes to tell her that her mother is very ill. She rushes to her parents’ house without telling her husband. In your opinion, is the husband justified in hitting or beating his wife for going out without telling him?

What if the wife is over-burdened with work one morning? Normally, she supervises the children’s play and keeps them neat and clean. But, one day, it has been raining since morning. While she is working hard to finish her house work, the children play in front of the house and get dirty. She does not have time to bathe them before her husband returns. The husband returns and sees that the children are dirty. In your opinion, is the husband justified in hitting or beating his wife for neglecting the children? To be clear, I am not asking you whether you think it is justified to hit or beat the children. I am asking whether you think the husband is justified in hitting or beating his wife in this situation.

What if the husband stays home out of laziness for several days, refusing to go out and work. His wife tells him they are running out of food and there is not enough money to buy food - and asks him to go out and work. The husband tells his wife to shut up. The wife argues with him. In your opinion, is the husband justified in hitting or beating his wife for arguing with him?

What if the wife is ill and her husband returns home at night and wants to have sex with her? She talks about her illness and refuses to have sex with the husband. She explains that she has stomach pains and a fever. In your opinion, is the husband justified in hitting or beating his wife for refusing to have sex with him?

What if the mother-in-law of the woman tells her to sweep the home-yard? The wife disobeys because she is busy caring for her baby. The mother-in-law complains to her son when he returns home. In your opinion, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife for disobeying her mother-in-law?

Variant Set C: wife willfully transgresses gender norms

I will now ask you some questions. Please listen to them and then answer thoughtfully. Please tell me what you think.

Sometimes a husband is annoyed or angered by things that his wife does. In your opinion, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife in the following situations:

What if a wife is home alone and goes to her parents’ house just for fun without telling her husband? In your opinion, is the husband justified in hitting or beating his wife for going out without telling him?

What if the wife often leaves her young children unsupervised and lets them go around looking dirty? Her husband has asked her many times before to supervise their play and keep them clean, but she does not pay attention to what he asks. In your opinion, is the husband justified in hitting or beating his wife for neglecting the children? To be clear, I am not asking you whether you think it is justified to hit or beat the children. I am asking whether you think the husband is justified in hitting or beating his wife in this situation.

What if the wife is quarrelsome by nature? She often disagrees with what her husband says and argues with him for no reason. In your opinion, is the husband justified in hitting or beating his wife for arguing with him?

What if the wife refuses to have sex with her husband whenever she is not in the mood? In your opinion, is the husband justified in hitting or beating his wife for refusing to have sex with him?

What if the wife’s mother-in-law tells her to sweep the home- yard, but the wife ignores that and spends the morning resting and chatting with her neighbor? In your opinion, is the husband justified in hitting or beating his wife for disobeying her mother-in-law?

Questions on perceived community norms about wife hitting or beating

Control Set D: DHS questions

I will now ask you some questions. Please listen to them and then answer thoughtfully. Please tell me what you think other people in your community believe.

Sometimes a husband is annoyed or angered by things that his wife does. According to other people in your community, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife in the following situations:

- If she goes out without telling him?

- 1a. If you had to choose, according to other people in your community, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife if she goes out without telling him?

- If she neglects the children?

- 2a. If you had to choose, according to other people in your community, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife if she neglects the children?

- If she argues with him?

- 3a. If you had to choose, according to other people in your community, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife if she argues with him?

- If she refuses to have sex with him?

- 4a. If you had to choose, according to other people in your community, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife if she refuses to have sex with him?

- If she does not obey elders in the family?

- 5a. If you had to choose, according to other people in your community, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife if she does not obey elders in the family?

Variant Set E: Wife unintentionally transgresses gender norms

I will now ask you some questions. Please listen to them and then answer thoughtfully. Please tell me what you think other people in your community believe.

Sometimes a husband is annoyed or angered by things that his wife does. According to other people in your community, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife in the following situations:

A wife is home alone; at this time someone comes to tell her that her mother is very ill. She rushes to her parents’ house without telling her husband. According to other people in your community, is the husband justified in hitting or beating his wife for going out without telling him?

What if the wife is over-burdened with work one morning? Normally, she supervises the children’s play and keeps them neat and clean. But, one day, it has been raining since morning. While she is working hard to finish her house work, the children play in front of the house and get dirty. She does not have time to bathe them before her husband returns. The husband returns and sees that the children are dirty. According to other people in your community, is the husband justified in hitting or beating his wife for neglecting the children? To be clear, I am not asking you whether other people in your community think it is justified to hit or beat the children. I am asking whether other people in your community think the husband is justified in hitting or beating his wife in this situation.

What if the husband stays home out of laziness for several days, refusing to go out and work. His wife tells him they are running out of food and there is not enough money to buy food - and asks him to go out and work. The husband tells his wife to shut up. The wife argues with him. According to other people in your community, is the husband justified in hitting or beating his wife for arguing with him?

What if the wife is ill and her husband returns home at night and wants to have sex with her? She talks about her illness and refuses to have sex with the husband. She explains that she has stomach pains and a fever. According to other people in your community, is the husband justified in hitting or beating his wife for refusing to have sex with him?

What if the mother-in-law of the woman tells her to sweep the home-yard? The wife disobeys because she is busy caring for her baby. The mother-in-law complains to her son when he returns home. According to other people in your community, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife for disobeying her mother-in-law?

Variant Set F: Wife willfully transgresses gender norms

I will now ask you some questions. Please listen to them and then answer thoughtfully. Please tell me what you think.

Sometimes a husband is annoyed or angered by things that his wife does. According to other people in your community, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife in the following situations:

What if a wife is home alone and goes to her parents’ house just for fun without telling her husband? According to other people in your community, is the husband justified in hitting or beating his wife for going out without telling him?

What if the wife often leaves her young children unsupervised and lets them go around looking dirty? Her husband has asked her many times before to supervise their play and keep them clean, but she does not pay attention to what he asks. According to other people in your community, is the husband justified in hitting or beating his wife for neglecting the children? To be clear, I am not asking you whether other people in your community think it is justified to hit or beat the children. I am asking whether other people in your community think the husband is justified in hitting or beating his wife in this situation.

What if the wife is quarrelsome by nature? She often disagrees with what her husband says and argues with him for no reason. According to other people in your community, is the husband justified in hitting or beating his wife for arguing with him?

What if the wife refuses to have sex with her husband whenever she is not in the mood? According to other people in your community, is the husband justified in hitting or beating his wife for refusing to have sex with him?

What if the wife’s mother-in-law tells her to sweep the home- yard, but the wife ignores that and spends the morning resting and chatting with her neighbor? According to other people in your community, is the husband justified in hitting or beating his wife for disobeying her mother-in-law?

Footnotes

The recent legal provisions of up-to-death penalty for violence against women in Bangladesh should discourage IPV against women (Bhuiya, Sharmin, and Hanifi 2003); however, access to legal services for poor, rural women is limited because such services are largely city-based and have associated psychic and financial costs. Discussions with villagers also suggest that IPV against women is neither condoned nor fully condemned, but that at times, one needs to resort to violence to control one’s wife. Thus, some argue that the deterrent provided by legal provisions is limited to more extreme forms of violence (Bhuiya et al. 2003).

Variations in the question, however, preclude strict comparisons (Yount et al. 2011). The question in 1999–2000 read: “It is normal for couples to have quarrels and disagreements. During those quarrels some husbands occasionally severely reprimand or even beat their wives. In your opinion, do you think a man would be justified to beat his wife: If she goes out without telling him? If she neglects the children? If she argues with her husband? If she fails to provide food on time?” The question in 2007 read: “Sometimes a husband is annoyed or angered by things that his wife does. In your opinion, is a husband justified in hitting or beating his wife in the following situations: If she goes out without telling him? If she neglects the children? If she argues with him? If she refuses to have sex with him? If she does not obey elders in the family?”

This age range differed slightly from the DHS (15 – 49 years) to include only adult women, defined as at least 18 years.

Few sampled households had more than one eligible woman. Reporting of age and date of birth was inconsistent for some respondents, and one selected respondent had a reported age of 62.

A limited number of questions were modified for suitability in the study villages. For example, the question on membership in community-based organizations included more detailed response options in our survey than in the 2007 Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS).

We did not collect data on personal experiences of IPV, and such experiences could have differed across experimental groups; however, the results in Table 1 suggest that the groups differed on very few observed attributes, including other measures of marital power (e.g., decision-making). Future research focused on understanding the determinants and consequences of attitudes about wife hitting or beating certainly could collect data on women’s own experiences of IPV.

For most transgressions, the ordering of question sets within pairs (A:D, D:A, B:E, E:B, C:F, F:C) did not affect the percentage of women responding yes to the personal attitudes questions for the DHS-control and unintended transgression variants of the questions. Yet, when women were asked first for their perceptions of community norms regarding hitting or beating a wife who willfully transgresses, they personally justified such violence marginally more often for two transgressions— going out without telling the husband and not obeying elders in his family.

Contributor Information

Kathryn M. Yount, Email: kyount@emory.edu, Hubert Department of Global Health, Emory University.

Nafisa Halim, Department of International Health, Boston University.

Sidney Ruth Schuler, Family Health International 360.

Sara Head, Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education, Emory University.

REFERENCES

- Alam S. Islam, Culture, And Women In A Bangladesh Village. In: Cornell VJ, editor. Voices of Islam. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers; 2007. pp. 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Asadullah MN, Chaudhury N. Reverse Gender Gap in Schooling in Bangladesh: Insights from Urban and Rural Households. Journal of Development Studies. 2009;45(8):1360–1380. [Google Scholar]

- Baden S, Green C, Goetz AM, Guhathakurta M. BRIDGE Report. Vol. 26. Brighton, U.K.: Institute for Development Studies, University of Sussex; 1994. Background Report on Gender Issues in Bangladesh. [Google Scholar]

- Bates LM, Schuler SR, Islam F, Islam MK. Socioeconomic Factors and Processes Associated With Domestic Violence in Rural Bangladesh. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2004;30(4):190–199. doi: 10.1363/3019004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhuiya A, Sharmin T, Hanifi SMA. Nature of Domestic Violence against Women in a Rural Area of Bangladesh: Implication for Preventive Interventions. Journal of Health, Population, and Nutrition. 2003;21(1):48–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury FD. Theorizing Patriarchy: The Bangladesh Context. Asian Journal of Social Science. 2009;37:599–622. [Google Scholar]

- DeMaio TJ. Social Desirability and Survey Measurement: A Review. In: Turner CF, Martin E, editors. Surveying Subjective Phenomena. Vol. 2. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman S. Shame and Honour: The Violence of Gendered Norms under Conditions of Global Crisis. Women's Studies International Forum. 2010;33:305–315. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HAFM, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH. Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence: Findings From the WHO Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence. Lancet. 2006;368:1260–1269. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holleman B. The Nature of the Forbid/Allow Asymmetry: Two Correlational Studies. Sociological Methods & Research. 1999;28(2):209–244. [Google Scholar]

- ICF Macro. Surveys with the Domestic Violence Module. 2010 http://www.measuredhs.com/topics/dv/dv_surveys.cfm.

- Johnson H, Ollus N, Nevala S. Violence against women: An international perspective. NY: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kandiyoti D. Bargaining With Patriarchy. Gender and Society. 1988;2:274–290. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer N. Subordination and Struggle: Women in Bangladesh. New Left Review. 1988;I/168:95–121. [Google Scholar]

- Kishor S, Johnson K. Profiling domestic violence–a multi-country study. Calverton, MD: ORC Macro; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Komter A. Hidden Power in marriage. Gender and Society. 1989;3(2):187–216. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig MA, Ahmed S, Hossain MA, Mozumder ABMKA. Women's Status and Domestic Violence in Rural Bangladesh: Individual- and Community-Level Effects. Demography. 2003;40:269–288. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Population Research and Training [NIPORT], Mitra and Associates, and Macro International. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2007. Dhaka, Bangladesh and Calverton, Maryland, USA: NIPORT, Mitra and Associates, and Macro International; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rugg D. Experiments in Wording Questions, II. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1941;5:91–92. [Google Scholar]

- Saltzman LE, Fanslow JL, McMahon PM, Shelley GA. Intimate Partner Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements. Atlanta (GA): National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1999. Version 1.0. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders DG, Lynch AB, Grayson M, Linz D. The Inventory of Beliefs About Wife Beating: The Construction and Initial Validation of a Measure of Beliefs and Attitudes. Violence and Victims. 1987;2(1):39–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler SR, Hashemi SM, Riley AP, Akhter S. Credit Programs, Patriarchy and Men’s Violence against Women in Rural Bangladesh. Social Science and Medicine. 1996;43(12):1729–1742. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler SR, Islam F. Women’s Acceptance of Intimate Partner Violence within Marriage in Rural Bangladesh. Studies in Family Planning. 2008;39(1):49–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler S, Lenzi R, Yount KM. Justification of Intimate Partner Violence in Rural Bangladesh: What Survey Questions Fail to Capture. Studies in Family Planning. 2011;42(1):21–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2011.00261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler S, Yount KM, Lenzi R. Justification of Wife Beating in Rural Bangladesh: A Qualitative Analysis of Gender Differences in Responses to Survey Questions. Violence against Women. forthcoming doi: 10.1177/1077801212465152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuman H, Presser S. Question Wording as an Independent Variable in Survey Analysis. Sociological Methods and Research. 1977;6(2):151–170. [Google Scholar]

- Schuman H, Presser S. Questions and Answers in Attitude Surveys: Experiments on Question Form, Wording, and Context. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton A. The Developmental Paradigm, Reading History Sideways, and Family Change. Demography. 2001;38(4):449–465. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourangeau R, Singer E, Presser S. Context Effects in Attitude Surveys: Effects on Remote Items and Impact on Predictive Validity. Sociological Methods & Research. 2003;31(4):486–513. [Google Scholar]

- Uthman O, Lawoko S, Moradi T. Factors Associated With Attitudes towards Intimate Partner Violence Against Women: A Comparative Analysis of 17 Sub-Saharan Countries. BMC International Health and Human Rights. 2009;9:14. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-9-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uthman O, Lawoko S, Moradi T. Sex Disparities in Attitudes Towards Intimate Partner Violence Against Women in Sub- Saharan Africa: A Socio-Ecological Analysis. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uthman O, Moradi T, Lawoko S. The Independent Contribution of Individual-, Neighbourhood-, and Country-Level Socioeconomic Position on Attitudes Towards Intimate Partner Violence Against Women in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Multilevel Model of Direct and Moderating Effects. Social Science and Medicine. 2009;68:1801–1809. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westoff CF, Bankole A. Mass Media and Reproductive Behavior in Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh. Analytical Reports No. 10. Calverton, Maryland: Macro International Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]