Abstract

Diuretics are widely used in the treatment of hypertension, although the precise mechanisms remain unknown. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs), cytochrome P450 (P450) epoxygenase metabolites of arachidonic acid, play critical roles in regulation of blood pressure. The present study was carried out to investigate whether EETs participate in the antihypertensive effect of thiazide diuretics [hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ)] and thiazide-like diuretics (indapamide). Male spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHRs) were treated with indapamide or HCTZ for 8 weeks. Systolic blood pressure, measured via tail-cuff plethysmography and confirmed via intra-arterial measurements, was significantly decreased in indapamide- and HCTZ-treated SHRs compared with saline-treated SHRs. Indapamide increased kidney CYP2C23 expression, decreased soluble epoxide hydrolase expression, increased urinary and renovascular 11,12- and 14,15-EETs, and decreased production of 11,12- and 14,15-dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acids in SHRs. No effect on expression of CYP4A1 or CYP2J3, or on 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid production, was observed, suggesting indapamide specifically targets CYP2C23-derived EETs. Treatment of SHRs with HCTZ did not affect the levels of P450s or their metabolites. Increased cAMP activity and protein kinase A expression were observed in the renal microvessels of indapamide-treated SHRs. Indapamide ameliorated oxidative stress and inflammation in renal cortices by down-regulating the expression of p47phox, nuclear factor-κB, transforming growth factor-β1, and phosphorylated mitogen-activated protein kinase. Furthermore, the p47phox-lowering effect of indapamide in angiotensin II–treated rat mesangial cells was partially blocked by the presence of N-(methylsulfonyl)-2-(2-propynyloxy)-benzenehexanamide (MS-PPOH) or CYP2C23 small interfering RNA. Together, these results indicate that the hypotensive effects of indapamide are mediated, at least in part, by the P450 epoxygenase system in SHRs, and provide novel insights into the blood pressure–lowering mechanisms of diuretics.

Introduction

The modern era of diuretic therapy for hypertension began in 1957 when Novello and Sprague synthesized the thiazide diuretic, chlorothiazide. Further modification of the benzothiadiazine core led to the synthesis of hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) and the thiazide-like diuretics: chlorthalidone (phthalimidine), metolazone (quinazolinone), and indapamide (indoline). Indapamide binds and inhibits the Na+-Cl− cotransporter in the distal convoluted tubule and connecting tubule but does not contain the benzothiadiazine core (Reilly et al., 2010). Despite similarities to other members of the thiazide family, indapamide has unique features that render it a particularly efficacious and advantageous antihypertensive agent (Sassard et al., 2005).

Indapamide is a relatively weak diuretic that has been shown to produce a significant and sustained reduction in blood pressure with a lower incidence of serious hypokalemia and hyperglycemia (Ambrosioni et al., 1998), and retains efficacy in patients with chronic kidney disease (Madkour et al., 1996). It has been demonstrated to reduce left ventricular hypertrophy to a greater degree than enalapril or atenolol monotherapy (Gosse et al., 2000; de Luca et al., 2004; Dahlof et al., 2005). It is also effective in reducing microalbuminuria in patients with diabetes and hypertension (Puig et al., 2007). Additional mechanisms by which indapamide may exert its antihypertensive effects have been proposed (Sassard et al., 2005). Indapamide induces an increase in the levels of prostacyclin, a cyclooxygenase-derived metabolite of arachidonic acid (AA), in vascular smooth muscle cells (Uehara et al., 1990). This raises the possibility that other AA metabolites may also play a role in the antihypertensive effects of indapamide.

In addition to the cyclooxygenases, AA can be metabolized by enzymes of the cytochrome P450 (P450) superfamily. The P450 epoxygenases generate 5,6-, 8,9-, 11,12-, and 14,15-epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs), which are further metabolized to their corresponding less-active dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acids (DHETs) by soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) (Fleming, 2001). The P450 ω-hydroxylases produce 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE) (Zhao and Imig, 2003). Both EETs and 20-HETE are involved in the regulation of vascular function (Zhao and Imig, 2003). In the renal microcirculation, 20-HETE promotes vasoconstriction by blocking large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels (Imig et al., 1996b) and stimulating l-type Ca2+ channels (Miyata and Roman, 2005), which contribute to an increase in blood pressure. On the other hand, EETs, which have been identified as endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors, promote vasodilation in the preglomerular arterioles via activation of renal smooth muscle cell Ca2+-activated K+ channels, therefore leading to hyperpolarization of vascular smooth muscle cells and reduction in blood pressure. EETs also markedly enhance the production of atrial natriuretic peptide in the heart, which contributes to vasodilation and natriuretic effects (Xiao et al., 2010). The vasodilatory properties of EETs have been well characterized in many animal models.

The CYP2C subfamily enzymes are the major P450 epoxygenases in the kidney. In particular, CYP2C23 is the predominant enzyme expressed in the rat kidney and converts AA to 8,9-EET, 11,12-EET, and 14,15-EET in a ratio of 1:2:1 (Imaoka et al., 1993). Furthermore, CYP2C23 can increase levels of hydroxy-EETs (HEETs) (Muller et al., 2004), which are endogenous activators of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α (PPARα). PPARα activators are also highly expressed in the kidney (Braissant et al., 1996) and exert antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects (Devchand et al., 1996; Diep et al., 2002; Kono et al., 2009). The production of P450 metabolites in the kidney is altered in rodent models of hypertension such as the spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR) (Sacerdoti et al., 1989; Yu et al., 2000), and it is likely that changes in this system contribute to the abnormalities in renal function in these models.

In this study, we investigated the possibility that the beneficial effects of indapamide in SHRs may be mediated through induction of P450 enzymes and alterations in levels of EETs or 20-HETE.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The protocol was approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of the Animal Research Committee of Tongji College. Eleven-week-old male SHRs and Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) rat controls were obtained from the Experimental Animal Center of Beijing (Beijing, China). Rats were treated daily with indapamide (1 mg/kg per day; Servier, Tianjin, China) and HCTZ (20 mg/kg per day; Qingdao Huanghai Pharmaceutical Co., LTD, Qingdao, China), or saline (0.9% NaCl) via gastric gavage for 8 weeks.

Measurement of Blood Pressure.

Systolic blood pressure was measured every 2 weeks at room temperature using tail-cuff plethysmography as described previously (Xiao et al., 2010). At 8 weeks after drug administration, the rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital (40 mg/kg i.p.) and a microtransducer catheter (SPR-838; Millar Instruments, Inc., Houston, TX) was inserted via the right carotid artery into the left ventricle according to a method described previously to measure blood pressure invasively (Xiao et al., 2010).

Cardiac Function Study.

Cardiac function was measured by echocardiograph with VIVID 7 (General Electric, Milwaukee, WI), equipped with a 15-MHz linear array ultrasound transducer. Parameters needed for the calculation of cardiac function and dimensions were measured from a minimum of five systole-diastole cycles. Left ventricular end-systolic diameter (LVESD) and left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD) were measured from left ventricular (LV) M-mode tracing (with a sweep speed of 50 mm/sec) at the papillary muscle level: LV fractional shortening (FS) and ejection fraction (EF), measures of LV systolic function, were calculated from LV M-mode by the following equations:

Isolation of Thoracic Aortic Rings and Determination of Vascular Function.

Thoracic aortic rings were prepared as described previously (Xiao et al., 2010). We examined the responsiveness of aortic rings from rats treated with saline, indapamide or HCTZ to norepinephrine and acetylcholine with a multichannel physiologic recorder (ML-840 PowerLab; ADInstrument Pty Ltd., Bella Vista, NSW, Australia).

Isolation of Renal Microvessels.

Renal microvessels were isolated according to a method described previously (Imig et al., 2001), collected, rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80°C until use.

Determination of 11,12- and 14,15-DHETs, 11,12- and 14,15-EETs, and 20-HETE in Urine and Tissues.

An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Detroit R&D Inc., Detroit, MI) was used to measure the concentrations of 11,12- and 14,15-EETs and their stable metabolites—11,12- and 14,15-DHETs and 20-HETE—in urine and tissues, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The amount of 11,12- and 14,15-EETs was quantitated by calculating the difference between total acidified 11,12- and 14,15-DHETs and non-acidified 11,12- and 14,15-DHETs, respectively, as described (Xiao et al., 2010).

Western Blotting.

Western blot analysis was performed as described previously (Wang et al., 2003). Antibodies against CYP2C23, CYP2J2, CYP4A1 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), protein kinase A (PKA), sEH, p47phox, p67phox, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), p-MAPK, superoxide dismutase (SOD)-1 SOD-2, transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), p-inhibitor of κβα (Ικβα), Ικβα, nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), and β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were used.

cAMP and Malondialdehyde Assays.

cAMP levels in renal tissues were evaluated using the cAMP XP Assay Kit (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Renal malondialdehyde (MDA) levels were measured as described previously (Li et al., 2010).

Evaluation of Renal and Aortic Injury and Cardiac Hypertrophy.

Urinary microalbumin levels were measured using the Rat MALB enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Nanjing Jiancheng, Nanjing, China). Kidney sections (6 µm) were stained with sirius red and hematoxylin-eosin. Immunohistochemical detection of CD68 was performed as described previously (Xiao et al., 2010), using CD68 antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). Vessel wall collagen was assessed by sirius red staining. Heart sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin. Cardiomyocyte diameter and the percentage of interstitial collagen content in the kidney were quantified using the HAIPS Pathologic Imagic Analysis System (Tongji Qianping Image Company, Wuhan, China).

Effects of Indapamide on CYP2C23 Production in HBZY-1 Cells.

Rat renal mesangial (HBZY-1) cells were transfected with CYP2C23 small interfering RNA (siRNA) (200 nM) or treated with N-(methylsulfonyl)-2-(2-propynyloxy)-benzenehexanamide (MS-PPOH), a specific inhibitor of P450 epoxygenase, 10 μM. Transfected or treated cells were incubated with/without indapamide (10 μM) and angiotensin II (Ang II) (100 nM) for 24 hours, after which the cells were collected for western blot analysis.

Statistical Analysis.

Values of quantitative results were presented as mean ± S.E.M. The data were analyzed with single-factor analysis of variance using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). Statistical significance was accepted if P < 0.05.

Results

Treatment with Diuretics Lowers Blood Pressure in SHRs.

Administration of indapamide or HCTZ for 8 weeks had no effect on the blood pressure of WKY control rats; however, treatment of SHRs with either drug decreased blood pressure by 16.9 and 15.4 mm Hg, respectively, compared with saline-treated controls (Supplemental Fig. 1A). Prior to sacrifice at the 8-week time point, the carotid intra-arterial pressure was measured, and the results were consistent with the noninvasive tail-cuff measurements (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Moreover, analysis of cardiac hemodynamics showed that dp/dtmax was increased in indapamide-treated SHRs compared with saline-treated SHRs (Supplemental Fig. 1C). Measurement of cardiac function by echocardiography showed that EF and FS were increased in indapamide-treated SHRs compared with saline-treated SHRs, but not in HCTZ-treated SHRs (Supplemental Fig. 1, D–E).

Renal CYPC23 Expression and 11,12- and 14,15-EET Levels Are Elevated by Indapamide in SHRs.

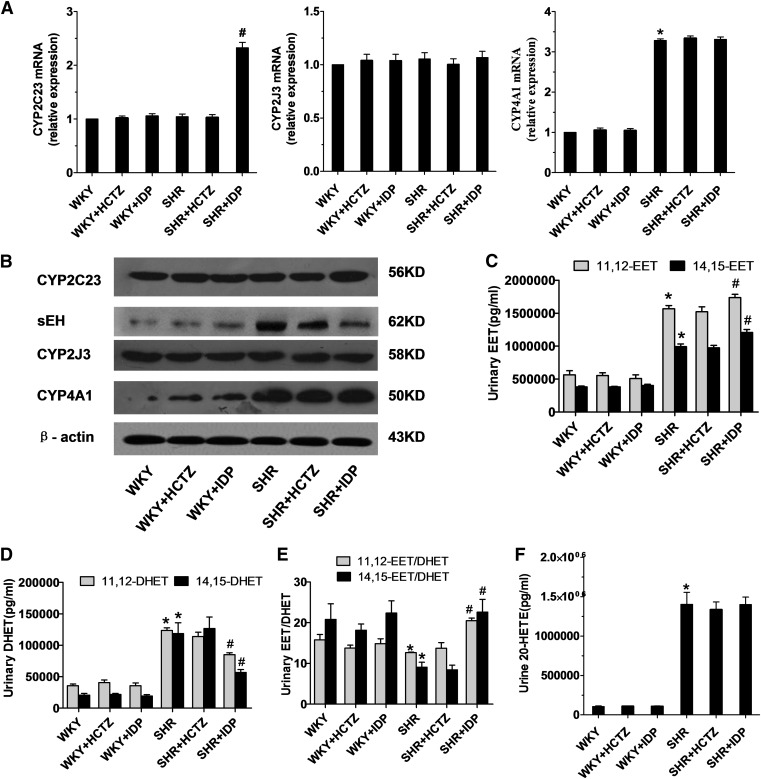

To investigate whether renal P450s play a role in the antihypertensive effect of indapamide, we quantitatively analyzed the mRNA expression of two P450 epoxygenases, CYP2C23 and CYP2J3, and an ω-hydroxylase, CYP4A1, in the kidney by real-time polymerase chain reaction (Supplemental Table 1). As shown in Fig. 1A, CYP2C23 mRNA levels were upregulated by 2.3-fold in indapamide-treated SHRs compared with saline-treated SHRs, whereas levels of CYP2J3 and CYP4A1 remained unchanged. Treatment with HCTZ had no effect on expression of P450s in the rats. In addition, the protein expression of CYP2C23 was increased in indapamide-treated SHRs (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, both indapamide and HCTZ decreased the protein expression of sEH in SHRs, although indapamide reduced it to a greater degree (Fig. 1B). To estimate P450 activity, levels of 11,12- and 14,15-EETs and 20-HETE were measured. Indapamide increased levels of 11,12- and 14,15-EETs (Fig. 1C) and decreased levels of 11,12- and 14,15-DHETs (Fig. 1D) in the urine of SHRs compared with saline controls. As a result, the EET:DHET ratio was increased by 2.5-fold (Fig. 1E). No significant differences in 11,12- and 14,15-DHETs or 11,12- and 14,15-EETs were observed in HCTZ-treated SHRs or any WKY groups. Meanwhile, the levels of 20-HETE in urine were markedly increased in SHRs compared with WKY rats (Fig. 1F), but were unaffected by treatment with indapamide or HCTZ.

Fig. 1.

Expression of P450 enzymes in the kidney and urinary levels of 11,12- and 14,15-EETs, 11,12- and 14,15-DHETs, and 20-HETE measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits. Kidneys and urine were collected from SHRs and WKY rats treated with saline, indapamide (IDP), or HCTZ. (A) mRNA levels of CYP2C23, CYP2J3, and CYP4A1 were determined by real-time polymerase chain reaction and normalized to GAPDH. N = 5; *P < 0.05 versus saline-treated WKYs; #P < 0.05 versus saline-treated SHRs. (B) Representative western blot depicting the protein expression of CYP2C23, sEH, CYP2J3, and CYP4A1. N = 3, duplicated three times. (C) 11,12-EET and 14,15-EET ratios. (D) 11,12-DHET and 14,15-DHET ratios. (E) EET:DHET ratios. (F) 20-HETE levels. N = 5; *P < 0.05 versus saline-treated WKYs; #P < 0.05 versus saline-treated SHRs.

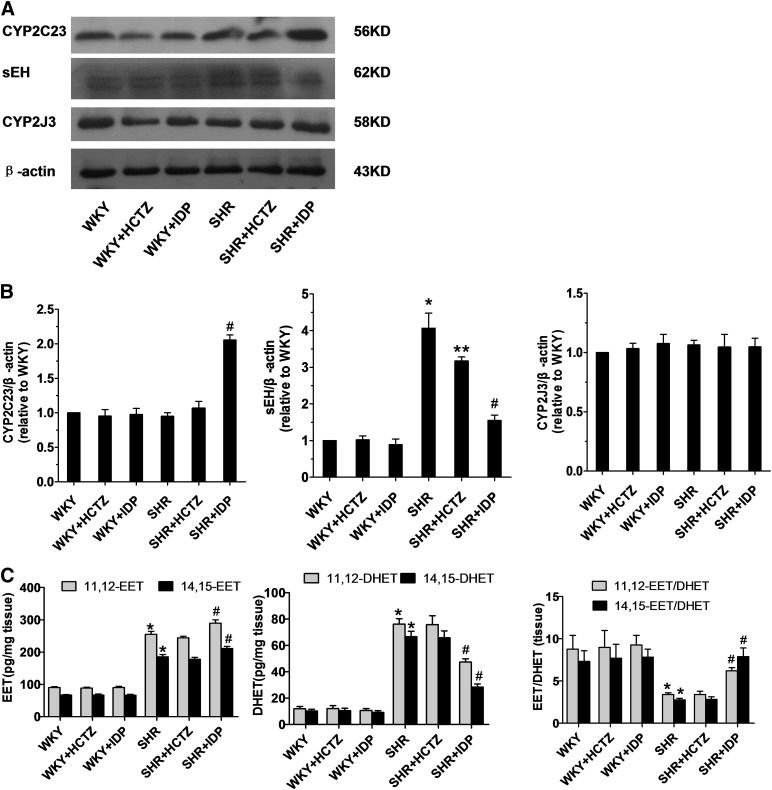

In addition, P450 enzyme expression and EET levels were assessed in renal microvessels. Indapamide increased CYP2C23 expression and decreased sEH expression in SHR microvessels relative to saline controls, while levels of CYP2J3 were not significantly different between the groups (Fig. 2, A–D). Furthermore, treatment of SHRs with indapamide increased and decreased levels of 11,12- and 14,15-EETs (Fig. 2E) and 11,12- and 14,15-DHETs, respectively (Fig. 2F), in the microvessels. No significant differences in 11,12- and 14,15-DHETs or 11,12- and 14,15-EETs were observed in HCTZ-treated SHRs or any WKY groups.

Fig. 2.

Levels of P450 enzymes and their metabolites in the renal microvessels. Renal microvessels were isolated from WKYs and SHRs treated with saline, indapamide (IDP), or HCTZ. (A and B) Representative western blots (A) and densitometry analyses (B) of CYP2C23, sEH, and CYP2J3. N = 3, duplicated three times; *P < 0.05 versus saline-treated WKYs; **,#P < 0.05 versus saline-treated SHRs. (C) 11,12-EET and 14,15-EET levels, 11,12-DHET and 14,15-DHET levels, and EET/DHET ratios were determined via an enzyme-linked immunosorbetn assay (ELISA) kit and normalized to the amount of protein in the tissues. N = 6; *P < 0.05 versus WKYs; #P < 0.05 versus saline-treated SHRs.

These results suggest that indapamide, but not HCTZ, stimulates CYP2C23 to generate more EETs without affecting the levels of other P450 enzymes and their metabolites.

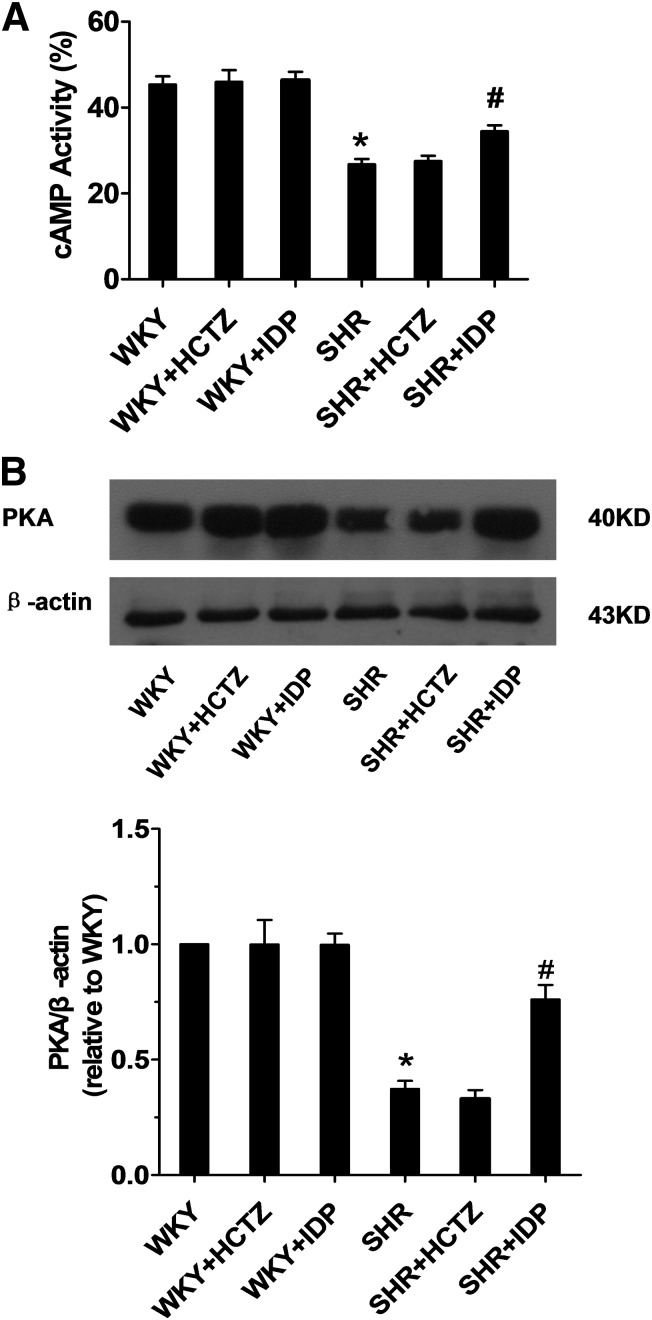

Indapamide Increases cAMP Levels and PKA Expression in SHR Renal Microvessels.

The vasodilatory effects of EETs in the renal vasculature have been associated with an increase in cAMP levels and can be blocked by inhibitors of cAMP and PKA signaling (Carroll et al., 2006). To investigate whether these components were altered with indapamide treatment in SHRs, renal microvessels were isolated. Interestingly, both cAMP levels (Fig. 3A) and PKA expression (Fig. 3B) were increased in indapamide-treated SHRs compared with saline-treated SHRs, suggesting that indapamide may increase vasodilation via a cAMP/PKA-dependent pathway. No significant differences in levels of cAMP or PKA were observed in HCTZ-treated SHRs or in any WKY groups.

Fig. 3.

Renal vascular cAMP levels and PKA expression in rats. Renal microvessels were isolated from SHRs and WKY rats treated with saline, indapamide (IDP), or HCTZ. (A) cAMP levels in renal microvessels were determined using the cAMP assay kit. N = 8; *P < 0.05 versus saline-treated WKYs; #P < 0.05 versus saline-treated SHRs. (B) Representative western blot and densitometry analysis for PKA. N = 3, duplicated three times; *P < 0.05 versus WKYs; #P < 0.05 versus saline-treated SHRs.

Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in the Renal Cortex of SHRs Are Attenuated with Indapamide Treatment.

In addition to increasing EET production, CYP2C23 is known to upregulate the expression of HEETs, endogenous PPARα activators that have both antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties (Muller et al., 2004). To investigate whether indapamide affects oxidative stress and inflammation, both of which are commonly observed in SHRs, renal cortices were isolated. Renal tissues from SHRs displayed increased levels of MDA, a marker for oxidative stress (Fig. 4A), and elevated expression levels of two NADPH oxidase subunits (p47phox and p67phox), as compared with that from WKY rats (Fig. 4B). Treatment of SHRs with indapamide or HCTZ significantly decreased levels of MDA (Fig. 4A) and prevented the increase in the expression of p47phox and p67phox (Fig. 4, B and C). SOD-1 and SOD-2 were decreased in SHRs compared with WKY rats, but were markedly increased with HCTZ treatment, while SOD-2 was subtly increased with indapamide treatment (Fig. 4, B and D). In addition, indapamide, but not HCTZ, attenuated renal inflammatory responses by significantly decreasing the expression of CD68 and p65-NF-κB by 25 and 23%, respectively (Fig. 4, E and F). Meanwhile, immunohistochemistry against CD68 showed that indapamide or HCTZ treatment decreased CD68-positive cells relative to the marked increase in saline-treated SHRs (Supplemental Fig. 2A). Furthermore, HCTZ treatment decreased phosphorylated Iκβα, while indapamide or HCTZ treatment increased total Iκβα expression (Fig. 4F). Protein levels of TGF-β1 and the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) were also enhanced in SHRs; treatment with indapamide or HCTZ decreased these effects (Supplemental Fig. 2, B–D). No differences in pro-oxidant or inflammatory factors were observed among WKY groups.

Fig. 4.

The effects of indapamide or HCTZ on oxidative stress and inflammation in the renal cortex. Renal cortices were isolated from SHRs and WKY rats treated with saline, indapamide (IDP), or HCTZ. (A) MDA levels were measured as an indicator of oxidative stress, using a commercial assay kit. N = 5; *P < 0.05 versus saline-treated WKYs; **,#P < 0.05 versus saline-treated SHRs. Representative western blots (B) and corresponding densitometry analyses (C–F) of p47phox, p67phox, SOD-1, SOD-2, CD68, p65-NF-κB, p-Iκβα, and Iκβα. N = 3, duplicated three times; *P < 0.05 versus saline-treated WKYs; **,#P < 0.05 versus saline-treated SHRs.

Indapamide Prevents Renal and Aortic Damage and Myocardial Hypertrophy.

Renal damage (Feld et al., 1990) and left ventricular hypertrophy are often observed in SHRs. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of renal structures showed that increased solidified glomeruli (a glomerulopathy) in saline-treated SHRs were decreased with indapamide or HCTZ treatment (Supplemental Fig. 3A). Collagen staining of kidney sections revealed that indapamide or HCTZ significantly reduced the renal collagen content in SHRs compared with saline controls (Supplemental Fig. 3, B and C). This was associated with a decrease in albuminuria, suggesting that renal damage is attenuated by indapamide or HCTZ in these hypertensive rats (Supplemental Fig. 3D). Furthermore, measurement of serum creatinine by picric acid showed that the increased serum creatinine seen in saline-treated SHRs was decreased by treatment with indapamide or HCTZ (Supplemental Fig. 3E). Analysis of collagen in the aorta cell wall showed that indapamide or HCTZ treatment decreased collagen deposition in the intima-media and ameliorated oxidative stress (Supplemental Fig. 4, A and B). Measurement of vascular function by artery rings showed that contraction in response to norepinephrine decreased, and dilation in response to acetylcholine increased in aortic rings from HCTZ- and indapamide-treated SHRs compared with SHR controls (Supplemental Fig. 4C). We also evaluated the degree of myocardial hypertrophy in SHRs by measuring cardiomyocyte diameter in hematoxylin and eosin–stained heart sections and calculating the ratio of left ventricular weight:body weight (mg/g). A marked reduction in cardiomyocyte diameter (Supplemental Fig. 5, A and B) and the ratio of left ventricular weight:body weight (Supplemental Fig. 5C) was observed in indapamide-treated SHRs compared with saline-treated SHRs, suggesting that indapamide also attenuates myocardial hypertrophy in hypertension.

Indapamide-Induced Reduction of p47phox Is CYP2C23-Dependent in HBZY-1 Cells.

To confirm the role of CYP2C23 in the effects of indapamide in the kidney, we evaluated the Ang II–induced increase in p47phox expression in rat mesangial (HBZY-1) cells that were either treated with MS-PPOH, a specific P450 epoxygenase inhibitor, or transfected with CYP2C23 siRNA. A 50% reduction in CYP2C23 protein was achieved in CYP2C23 siRNA-transfected cells. Treatment of control HBZY-1 cells with Ang II significantly increased the expression of p47phox and p67phox. Addition of indapamide to these cells decreased the Ang II–mediated induction in p47phox and p67phox expression. However, the p47phox or p67phox-lowering effect of indapamide was partially blocked in cells treated with MS-PPOH or transfected with CYP2C23 siRNA (Fig. 5, A and B), which also exhibited significant decreases in CYP2C23 expression (Fig. 5C). These results further suggest that the antioxidant effects of indapamide are mediated via CYP2C23 in the kidney.

Fig. 5.

The effects of P450 inhibition and indapamide on the Ang II–induced increase in p47phox expression in rat renal mesangial (HBZY-1) cells. Cells were transfected with CYP2C23 siRNA (200 nM) or treated with MS-PPOH (10 μM) in the presence/absence of indapamide (IDP; 10 μM) and Ang II (100 nM) for 24 hours. (A and B) Representative western blots and corresponding densitometry analyses of p47phox and p67phox in MS-PPOH–treated and CYP2C23 siRNA-transfected cells. N = 3, duplicated three times; *P < 0.05 versus dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO); #P < 0.05 versus Ang II; **P < 0.05 versus Ang II + IDP. (C) Densitometry analyses of CYP2C23 in MS-PPOH–treated and CYP2C23 siRNA-transfected cells. N = 3, duplicated three times; *P < 0.05 versus Ang II; #P < 0.05 versus Ang II + IDP.

Discussion

This study was undertaken to investigate the effect of indapamide on blood pressure in hypertensive rats and the mechanisms involved. The results showed that indapamide reduced blood pressure in SHRs and altered the expression of renal CYP2C23 and sEH, leading to increases in EETs and decreases in DHETs. Indapamide did not have significant effects in WKY control rats. Interestingly, HCTZ decreased blood pressure in the SHRs to a similar degree as indapamide, but failed to affect renal P450 expression or production of EETs/DHETs in either urine or renal tissue. These results imply that CYP2C23-derived EETs may be involved in the antihypertensive effect of indapamide, but not of HCTZ.

CYP2C isoforms are considered to be the major arachidonic acid epoxygenases in the kidney. In particular, CYP2C23 is the major epoxygenase expressed in rat kidney and converts AA to 8,9-, 11,12-, and 14,15-EET (Holla et al., 1999). Among these, 11,12-EET is the most active vasodilator in the preglomerular vasculature (Imig et al., 1996a) and a potent anti-inflammatory epoxide (Node et al., 1999). Induction of CYP2C23 not only increases the levels of EETs, but also stimulates the endogenous PPARα activator, HEET (Muller et al., 2004). PPARα is highly expressed in the kidney (Braissant et al., 1996) and exerts both antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects (Devchand et al., 1996; Diep et al., 2002; Kono et al., 2009). These characteristics, combined with our observations, suggest that the hypotensive effects of indapamide may be due, at least in part, to increases in CYP2C23 expression and EET production.

EETs have been identified to be endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors (Campbell et al., 1996) and the predominant products generated by a rat CYP2C23 present in isolated renal microvessels (Imig et al., 2001). The current study shows that indapamide increased CYP2C23 expression and 14,15-EET levels in renal microvessels of SHRs. Indapamide also decreased sEH expression, which may have a synergistic effect with CYP2C23 in increasing 14,15-EET production and decreasing the levels of DHETs, which are less active in the vasculature (Imig et al., 1996a). Previous studies have demonstrated that 11,12-EET analogs increase cAMP but not cGMP levels (Imig et al., 2008) and also that EETs dilate renal arteries by activating renal smooth muscle cell Ca2+-activated K+ channels (Zou et al., 1996), which are dependent on PKA activation (Imig et al., 1999). Our data showed that treatment of SHRs with indapamide also increased cAMP levels and PKA expression in isolated renal microvessels. It is possible that these changes in cAMP and PKA may increase dilation in the renal vasculature, thus leading to a decrease in blood pressure.

It is well known that renal oxidative stress, inflammation, and hypertension are highly interrelated (Rodriguez-Iturbe et al., 2001; Vaziri, 2004; Touyz, 2005); modulating any one of them could affect the status of the other two (Nava et al., 2003; Rodriguez-Iturbe et al., 2003). Meanwhile, antioxidants are known to reduce blood pressure in SHRs (Nava et al., 2003; Rodriguez-Iturbe et al., 2003), and NF-κB blockade reduces oxidative stress and blood pressure in SHRs (Elks et al., 2009). A recent study showed that expression of NADPH oxidase subunits, p47phox and p67phox, is upregulated in the kidneys of SHRs (Chabrashvili et al., 2002). In addition, studies have shown that SOD activity is suppressed in SHRs (Ito et al., 1995; Ushiyama et al., 2004). SOD, catalyzing the dismutation of unstable superoxide anions to H2O2, acts as the first line of defense against reactive oxygen species. Thus, treatment with SOD mimetics decreases superoxide anion production and attenuates the development of hypertension in SHRs (Schnackenberg et al., 1998). The data presented in this study indicate that indapamide ameliorated oxidative stress in the renal cortex of SHRs, potentially by decreasing p47phox and p67phox expression and increasing SOD expression. It also attenuated renal inflammatory responses by decreasing p65-NF-κB expression, which may be associated with the anti-inflammatory effects of 11,12-EET or HEETs.

Oxidative stress can trigger the activation of redox-sensitive signal transduction pathways such as those that include NF-κB, which in turn intensifies oxidative stress (Vaziri and Rodriguez-Iturbe, 2006) and upregulates JNK and p38 MAPK pathways (Hehner et al., 2000). Moreover, JNK and p38 MAPK play important roles in renal fibrosis, acting downstream of TGF-β1. Previous studies showed that blockade of JNK abrogates the pathogenesis of interstitial fibrosis (Ma et al., 2007) and a p38 MAPK inhibitor reduces extracellular matrix production in the rat kidney (Stambe et al., 2004). The role of TGF-β1 in renal fibrosis is widely accepted (Schnaper et al., 2002). Enhanced expression of TGF-β1 has been shown to contribute to the development of renal fibrosis in hypertensive rats (Gallego et al., 2001). The present study revealed that indapamide treatment reduced renal collagen deposition, decreased levels of TGF-β1, and inhibited the activation of p38 and JNK in the renal cortex of SHRs, suggesting that indapamide may reduce renal inflammation and fibrosis by decreasing oxidative stress and MAPK activation. Furthermore, indapamide attenuated oxidative stress by increasing CYP2C23 expression in vitro in HBZY-1 cells, which was partially abrogated by addition of MS-PPOH, a specific P450 epoxygenase inhibitor, or transfection with CYP2C23 siRNA.

In summary, the present study provides evidence that activation of the CYP2C23 epoxygenase pathway may be involved in the antihypertensive effect of indapamide. These data suggest that indapamide increases EET production via the induction of CYP2C23 and the inhibition of sEH. EET ameliorates the hypertension observed in SHRs by increasing cAMP and PKA expression in the renal microvessels and decreasing expression of the NADPH oxidase subunits p47phox, p67phox, NF-κB, and TGF-β1 in the renal cortex. However, HCTZ decreased blood pressure and ameliorated the oxidative stress and inflammation in the renal cortex without activating the P450 epoxygenase pathway, which will be investigated in the future.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

- 20-HETE

20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid

- AA

arachidonic acid

- Ang II

angiotensin II

- DHET

dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acid

- EET

epoxyeicosatrienoic acid

- EF

ejection fraction

- FS

fractional shortening

- HCTZ

hydrochlorothiazide

- HEET

hydroxy-EET

- Ικβα

inhibitor of κβα

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- LV

left ventricular

- LVESD

left ventricular end-systolic diameter

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MS-PPOH

N-(methylsulfonyl)-2-(2-propynyloxy)-benzenehexanamide

- MDA

malondialdehyde

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

- P450

cytochrome P450

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PPARα

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α

- sEH

soluble epoxide hydrolase

- SHR

spontaneously hypertensive rat

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- TGF-β1

transforming growth factor-β1

- WKY

Wistar-Kyoto rat

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Ma, Lin, Y. Wang, Chen, D. W. Wang.

Conducted experiments: Ma, Lin.

Performed data analysis: Ma, Lin, Y. Wang, D. W. Wang.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Ma, Lin, D. W. Wang, Cheng, Zeldin.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the 973 Projects [2012CB517801 and 2012CB518004]; National Nature Science Foundation of China [31130031]; Key Project of The Ministry of Health of China; and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health [National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences] [Grant Z01 ES025034].

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Ambrosioni E, Safar M, Degaute JP, Malin PL, MacMahon M, Pujol DR, de Cordoüe A, Guez D. (1998) Low-dose antihypertensive therapy with 1.5 mg sustained-release indapamide: results of randomised double-blind controlled studies. European study group. J Hypertens 16:1677–1684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braissant O, Foufelle F, Scotto C, Dauça M, Wahli W. (1996) Differential expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): tissue distribution of PPAR-alpha, -beta, and -gamma in the adult rat. Endocrinology 137:354–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell WB, Gebremedhin D, Pratt PF, Harder DR. (1996) Identification of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids as endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors. Circ Res 78:415–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll MA, Doumad AB, Li J, Cheng MK, Falck JR, McGiff JC. (2006) Adenosine2A receptor vasodilation of rat preglomerular microvessels is mediated by EETs that activate the cAMP/PKA pathway. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 291:F155–F161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabrashvili T, Tojo A, Onozato ML, Kitiyakara C, Quinn MT, Fujita T, Welch WJ, Wilcox CS. (2002) Expression and cellular localization of classic NADPH oxidase subunits in the spontaneously hypertensive rat kidney. Hypertension 39:269–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlöf B, Gosse P, Guéret P, Dubourg O, de Simone G, Schmieder R, Karpov Y, García-Puig J, Matos L, De Leeuw PW, et al. PICXEL Investigators (2005) Perindopril/indapamide combination more effective than enalapril in reducing blood pressure and left ventricular mass: the PICXEL study. J Hypertens 23:2063–2070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Luca N, Mallion JM, O’Rourke MF, O’Brien E, Rahn KH, Trimarco B, Romero R, De Leeuw PW, Hitzenberger G, Battegay E, et al. (2004) Regression of left ventricular mass in hypertensive patients treated with perindopril/indapamide as a first-line combination: the REASON echocardiography study. Am J Hypertens 17:660–667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devchand PR, Keller H, Peters JM, Vazquez M, Gonzalez FJ, Wahli W. (1996) The PPARalpha-leukotriene B4 pathway to inflammation control. Nature 384:39–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diep QN, Amiri F, Touyz RM, Cohn JS, Endemann D, Neves MF, Schiffrin EL. (2002) PPARalpha activator effects on Ang II-induced vascular oxidative stress and inflammation. Hypertension 40:866–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elks CM, Mariappan N, Haque M, Guggilam A, Majid DS, Francis J. (2009) Chronic NF-kappaB blockade reduces cytosolic and mitochondrial oxidative stress and attenuates renal injury and hypertension in SHR. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296:F298–F305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feld LG, Cachero S, Van Liew JB, Zamlauski-Tucker M, Noble B. (1990) Enalapril and renal injury in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 16:544–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming I. (2001) Cytochrome p450 and vascular homeostasis. Circ Res 89:753–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego B, Arévalo MA, Flores O, López-Novoa JM, Pérez-Barriocanal F. (2001) Renal fibrosis in diabetic and aortic-constricted hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 280:R1823–R1829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosse P, Sheridan DJ, Zannad F, Dubourg O, Guéret P, Karpov Y, de Leeuw PW, Palma-Gamiz JL, Pessina A, Motz W, et al. (2000) Regression of left ventricular hypertrophy in hypertensive patients treated with indapamide SR 1.5 mg versus enalapril 20 mg: the LIVE study. J Hypertens 18:1465–1475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hehner SP, Breitkreutz R, Shubinsky G, Unsoeld H, Schulze-Osthoff K, Schmitz ML, Dröge W. (2000) Enhancement of T cell receptor signaling by a mild oxidative shift in the intracellular thiol pool. J Immunol 165:4319–4328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holla VR, Makita K, Zaphiropoulos PG, Capdevila JH. (1999) The kidney cytochrome P-450 2C23 arachidonic acid epoxygenase is upregulated during dietary salt loading. J Clin Invest 104:751–760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imaoka S, Wedlund PJ, Ogawa H, Kimura S, Gonzalez FJ, Kim HY. (1993) Identification of CYP2C23 expressed in rat kidney as an arachidonic acid epoxygenase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 267:1012–1016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imig JD, Dimitropoulou C, Reddy DS, White RE, Falck JR. (2008) Afferent arteriolar dilation to 11, 12-EET analogs involves PP2A activity and Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Microcirculation 15:137–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imig JD, Falck JR, Wei S, Capdevila JH. (2001) Epoxygenase metabolites contribute to nitric oxide-independent afferent arteriolar vasodilation in response to bradykinin. J Vasc Res 38:247–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imig JD, Inscho EW, Deichmann PC, Reddy KM, Falck JR. (1999) Afferent arteriolar vasodilation to the sulfonimide analog of 11, 12-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid involves protein kinase A. Hypertension 33:408–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imig JD, Navar LG, Roman RJ, Reddy KK, Falck JR. (1996a) Actions of epoxygenase metabolites on the preglomerular vasculature. J Am Soc Nephrol 7:2364–2370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imig JD, Zou AP, Stec DE, Harder DR, Falck JR, Roman RJ. (1996b) Formation and actions of 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid in rat renal arterioles. Am J Physiol 270:R217–R227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H, Torii M, Suzuki T. (1995) Decreased superoxide dismutase activity and increased superoxide anion production in cardiac hypertrophy of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clin Exp Hypertens 17:803–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono K, Kamijo Y, Hora K, Takahashi K, Higuchi M, Kiyosawa K, Shigematsu H, Gonzalez FJ, Aoyama T. (2009) PPARalpha attenuates the proinflammatory response in activated mesangial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296:F328–F336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YJ, Wang PH, Chen C, Zou MH, Wang DW. (2010) Improvement of mechanical heart function by trimetazidine in db/db mice. Acta Pharmacol Sin 31:560–569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma FY, Flanc RS, Tesch GH, Han Y, Atkins RC, Bennett BL, Friedman GC, Fan JH, Nikolic-Paterson DJ. (2007) A pathogenic role for c-Jun amino-terminal kinase signaling in renal fibrosis and tubular cell apoptosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 18:472–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madkour H, Gadallah M, Riveline B, Plante GE, Massry SG. (1996) Indapamide is superior to thiazide in the preservation of renal function in patients with renal insufficiency and systemic hypertension. Am J Cardiol 77:23B–25B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata N, Roman RJ. (2005) Role of 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE) in vascular system. J Smooth Muscle Res 41:175–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller DN, Theuer J, Shagdarsuren E, Kaergel E, Honeck H, Park JK, Markovic M, Barbosa-Sicard E, Dechend R, Wellner M, et al. (2004) A peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha activator induces renal CYP2C23 activity and protects from angiotensin II-induced renal injury. Am J Pathol 164:521–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nava M, Quiroz Y, Vaziri N, Rodriguez-Iturbe B. (2003) Melatonin reduces renal interstitial inflammation and improves hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284:F447–F454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Node K, Huo Y, Ruan X, Yang B, Spiecker M, Ley K, Zeldin DC, Liao JK. (1999) Anti-inflammatory properties of cytochrome P450 epoxygenase-derived eicosanoids. Science 285:1276–1279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puig JG, Marre M, Kokot F, Fernandez M, Jermendy G, Opie L, Moyseev V, Scheen A, Ionescu-Tirgoviste C, Saldanha MH, et al. (2007) Efficacy of indapamide SR compared with enalapril in elderly hypertensive patients with type 2 diabetes. Am J Hypertens 20:90–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly RF, Peixoto AJ, Desir GV. (2010) The evidence-based use of thiazide diuretics in hypertension and nephrolithiasis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5:1893–1903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Iturbe B, Pons H, Herrera-Acosta J, Johnson RJ. (2001) Role of immunocompetent cells in nonimmune renal diseases. Kidney Int 59:1626–1640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Zhan CD, Quiroz Y, Sindhu RK, Vaziri ND. (2003) Antioxidant-rich diet relieves hypertension and reduces renal immune infiltration in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 41:341–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacerdoti D, Escalante B, Abraham NG, McGiff JC, Levere RD, Schwartzman ML. (1989) Treatment with tin prevents the development of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Science 243:388–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassard J, Bataillard A, McIntyre H. (2005) An overview of the pharmacology and clinical efficacy of indapamide sustained release. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 19:637–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnackenberg CG, Welch WJ, Wilcox CS. (1998) Normalization of blood pressure and renal vascular resistance in SHR with a membrane-permeable superoxide dismutase mimetic: role of nitric oxide. Hypertension 32:59–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnaper HW, Hayashida T, Poncelet AC. (2002) It’s a Smad world: regulation of TGF-beta signaling in the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol 13:1126–1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stambe C, Atkins RC, Tesch GH, Masaki T, Schreiner GF, Nikolic-Paterson DJ. (2004) The role of p38alpha mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 15:370–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touyz RM. (2005) Molecular and cellular mechanisms in vascular injury in hypertension: role of angiotensin II. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 14:125–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehara Y, Shirahase H, Nagata T, Ishimitsu T, Morishita S, Osumi S, Matsuoka H, Sugimoto T. (1990) Radical scavengers of indapamide in prostacyclin synthesis in rat smooth muscle cell. Hypertension 15:216–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushiyama M, Morita T, Kuramochi T, Yagi S, Katayama S. (2004) Erectile dysfunction in hypertensive rats results from impairment of the relaxation evoked by neurogenic carbon monoxide and nitric oxide. Hypertens Res 27:253–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaziri ND. (2004) Roles of oxidative stress and antioxidant therapy in chronic kidney disease and hypertension. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 13:93–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaziri ND, Rodríguez-Iturbe B. (2006) Mechanisms of disease: oxidative stress and inflammation in the pathogenesis of hypertension. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 2:582–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Lin L, Jiang J, Wang Y, Lu ZY, Bradbury JA, Lih FB, Wang DW, Zeldin DC. (2003) Up-regulation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase by endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor involves mitogen-activated protein kinase and protein kinase C signaling pathways. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 307:753–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao B, Li X, Yan J, Yu X, Yang G, Xiao X, Voltz JW, Zeldin DC, Wang DW. (2010) Overexpression of cytochrome P450 epoxygenases prevents development of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats by enhancing atrial natriuretic peptide. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 334:784–794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z, Xu F, Huse LM, Morisseau C, Draper AJ, Newman JW, Parker C, Graham L, Engler MM, Hammock BD, et al. (2000) Soluble epoxide hydrolase regulates hydrolysis of vasoactive epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. Circ Res 87:992–998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Imig JD. (2003) Kidney CYP450 enzymes: biological actions beyond drug metabolism. Curr Drug Metab 4:73–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou AP, Fleming JT, Falck JR, Jacobs ER, Gebremedhin D, Harder DR, Roman RJ. (1996) Stereospecific effects of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids on renal vascular tone and K(+)-channel activity. Am J Physiol 270:F822–F832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.