Abstract

The Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) is a patient record-based database based upon a medical records-linkage system for all residents of the Olmsted County, MN, USA. This comprehensive system includes all health-care providers of patients resident in this geographically defined region. It uniquely enables long-term population-based studies of all medical conditions occurring in this population; their incidence and prevalence; permits examination of disease risk and protective factors, health resource utilization and cost as well as translational studies in rheumatic diseases.

Keywords: Rheumatic diseases, Epidemiology, Registry, Health sciences research, Outcomes, Cost

Introduction

Comprehensive community-based health-care information systems are rare in the USA, making it difficult and costly to conduct true population-based epidemiological, health services research and natural history studies across the full severity spectrum of rheumatic diseases. Most of these studies include only patients attending specialized centres or specialty clinics, those agreeing to participate in registries, populations covered by a single payor or respondents to surveys. In contrast, the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) maintains a medical records-linkage system for all residents of the Olmsted County, MN, USA that enables long-term population-based studies of incidence, prevalence, risk and protective factors, health services utilization, cost-effectiveness and, more recently, translational studies in rheumatic diseases. This review describes the unique research capabilities of the REP in the context of rheumatic diseases, with a particular focus on recent advances in availability of bioinformatics and translational resources. Interested readers are also encouraged to refer to an earlier review of the REP resources published in 2004 [1].

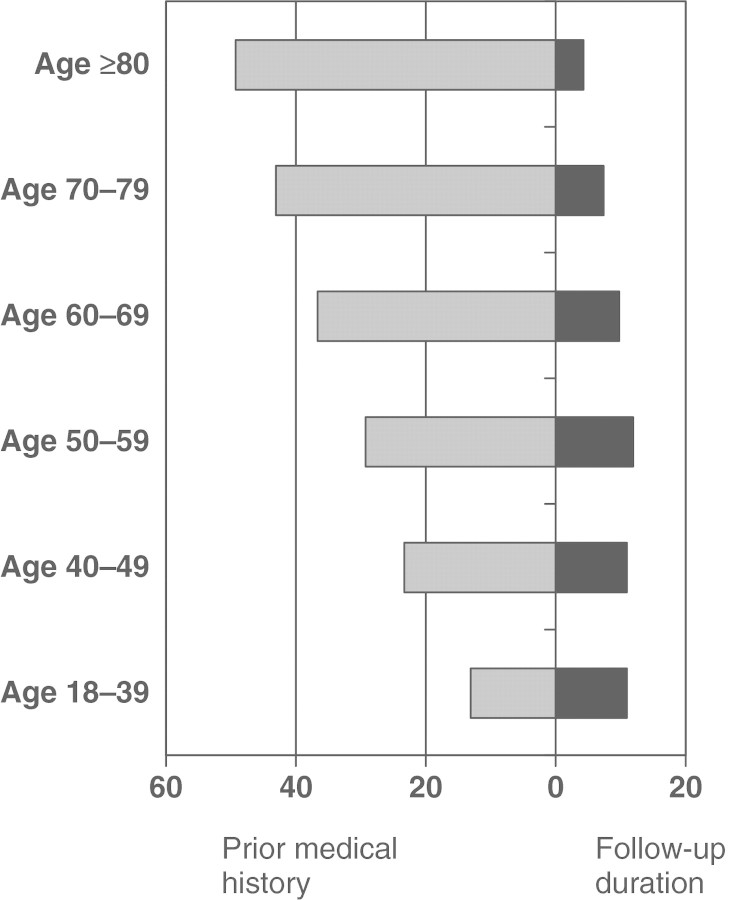

The REP links medical records generated by different health-care providers over many years to specific individuals, maintains an electronic index of diagnoses and surgical interventions, and provides an ongoing census of individuals as they move in and out of the community over time. Basic components of the REP are illustrated in Fig. 1. Subjects can be followed through their outpatient office, urgent care, emergency department and hospitalization contacts with all local health-care providers (e.g. Mayo Clinic, Olmsted Medical Center and affiliated hospitals and private practitioners), allowing for the longitudinal follow-up of a well-defined population-based cohort that currently includes approximately 125 000 subjects. Since the REP was established in 1966, more than 700 000 subjects have been included in its medical record , and it has supported several studies and provided the basis on which close to 100 publications on the aetiology and outcomes of rheumatic diseases occurring in this population over the entire lifetime of the community residents, from birth to death, have been completed. These rheumatic diseases include RA [2–44], JRA [45–50], PsA [51–54], OA [55], SLE [56], GCA and PMR [56–72], gout [73, 74], SS [75], Behçet’s disease [76] and AS [77].

Fig. 1.

REP structure.

What is unique about the REP as compared with other rheumatic disease databases?

The REP includes all conditions that come to medical attention in a geographically defined population and links the diagnostic codes to the extensive details incorporated in complete (inpatient and outpatient) contemporary and archived medical records for each resident of the Olmsted County. Unique capabilities of the REP are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Unique advantages of REP for population-based research in rheumatic diseases

| Construction of population-based cohorts consisting of virtually all clinically recognized cases across the full spectrum of the disease |

|

| Capacity for longitudinal follow-up of each member of every REP population-based cohort |

|

| Active follow-up |

|

| Passive follow-up is an hallmark of REP studies |

|

| Health services utilization and cost data |

|

HICD-A: Hospital adaptation of the ICD: international classification of diseases; HIPAA: health insurance portability and accountability act; ED: emergency department.

Each of the several rheumatic disease databases in the USA or Europe has strengths and limitations. For example, prospective registry-based data or surveys are available for some specific conditions [78–80], but most such studies must actively recruit subjects, which is expensive and increasingly hindered by non-response bias at baseline and additional subject loss during follow-up [81–83]. Nationwide registries of larger populations in northern Europe link diagnoses, but do not include the comprehensive medical information from individual medical records. Health Maintenance Organization databases have passive access to diagnoses and procedures for thousands of patients with rheumatic diseases, but are not population based; may have overrepresentation from the working public; fail to include care given in the community but outside the health plan [84]; and do not provide large volumes of longitudinal data because members often change their insurers, resulting in high turnover [85]. US Medicare and Medicaid data cover very large populations and can be accessed with proper permission, but the data available are limited to administrative or billing data rather than the detailed medical records indispensable to attribute signs, symptoms, and costs to a condition and to study the course of a disease [86]. Moreover, these populations are limited to specific age and socio-economic groups, and the resulting administrative data may be further subject to biases driven by local billing practices [87, 88]. In contrast to these registry resources, the REP includes essentially the entire population of the Olmsted County, and provides longitudinal information and linkage to the medical records for inpatient and outpatient visits, regardless of the socio-economic status, insurer, health-care setting, provider or disease severity.

The REP population databases for various rheumatic diseases: RA as an example

The REP maintains a records linkage system for the complete population as defined in the classic epidemiological literature [89, 90]. Indeed, the REP covers >98% of all medical care provided to the residents, regardless of age, socio-economic status or insurance coverage, and the local health-care providers span the spectrum from primary outpatient care through tertiary and critical hospital care including all medical and surgical specialties. Although best known as a tertiary referral centre, Mayo Clinic has always provided primary and secondary, as well as tertiary, care to the residents of the Olmsted County. Furthermore, in contrast to many other registry-based cohorts in the USA, a patient does not need to be seen by a rheumatologist to be included in a REP-based study cohort. Indeed, many of the REP rheumatic disease study cohorts (i.e. RA, JRA, SLE, GCA, PMR, PsA and scleroderma) include patients who were almost exclusively managed by internists or other primary-care providers.

RA is an excellent example of an ongoing population-based cohort in the Olmsted County. The RA incidence cohort dates back to 1955 and it was first assembled using the 1958 ARA criteria. Later, the cohort was reassembled based on the 1987 ACR classification criteria [91]. Since then, the same criteria have been consistently applied to ascertain nearly 1200 incident RA subjects as of 1 January 2008.

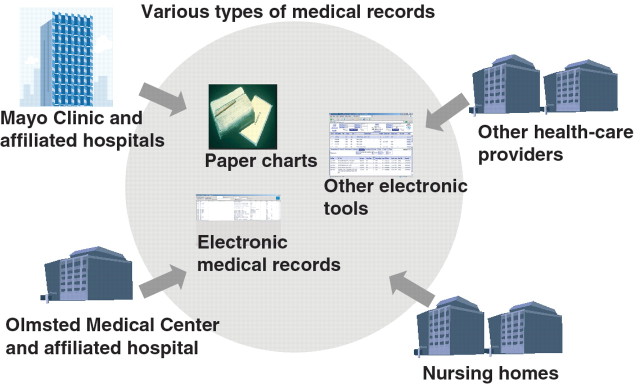

An important challenge in designing studies of risk factors and outcomes is identification of an appropriate source population for selection of unexposed cohorts or controls. In the case of REP, this is a straightforward process. Since all RA patients come from the precisely defined and closely monitored the Olmsted County population, controls can easily be sampled from the same population (Fig. 2). The REP maintains an enumeration of the local population because >95% of the Olmsted County population has at least one contact with a health care provider every 2–3 years and their medical informations are continuously entered into the REP data systems. This complete enumeration also creates a framework for random sampling of the general population for prospective studies, complete with address, telephone number and other contact information.

Fig. 2.

Sampling of study cohort using the REP.

Studies across the full spectrum of care regardless of health-care provider or insurance

The REP resources afford essentially complete information on the entire medical history of the Olmsted County residents, extending from date of first contact with any health-care provider in the Olmsted County through death (or emigration). Very few other databases allow study of patients across all health-care delivery settings and payors. The REP resources include all primary, secondary and tertiary levels of care and, with few exceptions (some local orthodontists, optometrists, chiropractors, rehabilitation therapists, psychiatrists and home health-care providers), all health-care delivery settings (including office visits; specialty consults; emergency department, hospital inpatient and outpatient encounters; and nursing home stays). The ability to study individuals as they undergo transition across health-care delivery settings affords a more complete understanding of health-care utilization and costs [11, 12], risk factors and outcomes [92]. For example, in a recent study [92], we were able to identify all residents who had autoantibody testing (irrespective of rheumatic disease status) at any of the health-care providers in the Olmsted County, not just the Mayo Clinic.

Studies of long-term causal associations and outcomes of rheumatic diseases

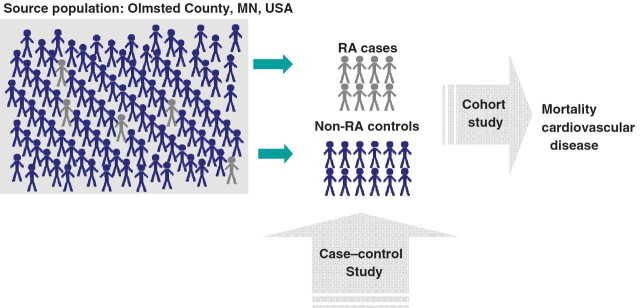

Rheumatic diseases may develop at almost any point in life and are the result of genetic, epigenetic, developmental and early-life events and risk factors. Therefore, only studies considering long-term exposures/risk factors may be able to clarify causal associations. For example, to design studies linking pregnancy or early-life events to rheumatic diseases, a follow-up of >60 years may be needed. Indeed, the REP-based studies of rheumatic diseases typically have a very long duration of medical history, both before and after disease diagnoses. For example, the RA incidence cohort contains a median of 30.5 years (25th percentile: 15.2 years, 75th percentile: 42.8 years) of available medical history before, and 9.5 years (25th percentile: 5.0 years, 75th percentile: 16.7 years) after RA incidence date. Figure 3 illustrates the median duration of medical history, both before and after RA incidence date in our cohort by decades of age.

Fig. 3.

Median length of medical history before RA incidence date and median follow-up after RA incidence date according to age at RA incidence.

The extent of medical history also allows studies across generations. The REP maintains a database of birth records for births in the Olmsted County, which allows identification of mothers. In an attempt to examine the risk of heart disease among children of women with RA, we identified the children of 441 women with RA and 441 women of similar age and sex without RA. We were able to identify 381 children of women with RA and 414 children of women without RA and followed them retrospectively through their medical records from birth to date (mean follow-up of 40 years; Crowson CS, data not published). This time frame requires the existence of historical archives or databases that were established and maintained in the past and can be used now to test aetiological hypotheses. Similarly, to efficiently explore the long-term effectiveness and safety of drug treatments, surgical interventions or preventive measures, it is essential to combine historical documentation of exposures with current follow-up. In a study that spanned several decades [93], we demonstrated a significant reduction in joint-related surgeries for patients diagnosed between 1985 and 1994, as compared with 1965–74 and 1975–84. Another excellent example of this unique strength is our studies describing trends in RA mortality, providing compelling ecological evidence that the improvements in morbidity and quality of life in RA have not led to improvements in survival [14]. As the time frame involved often spans decades, short-term studies may be unable to measure the associations and effects. Population-based historical cohort studies have been the hallmark of the REP-based rheumatic disease cohorts, and the ongoing collection, coding and storage of contemporary medical or surgical data are essential for cohort studies in the future.

Feasibility of different study designs (a population-based approach): retrospective cohort studies and case–control studies of RA and its comorbidities as examples

The unique capability of the REP to enumerate the entire population allows innovative research designs and analytical approaches. For example, the ability to ascertain all cases of a certain disease in the community permits the assessment of population-attributable risks, an approach rarely feasible in other observational studies [94]. In another study examining the association between oral contraceptives and RA, we were able to demonstrate that the population-attributable risk was small and that the decline in RA incidence could not be explained by oral contraceptive use because the proportion of women exposed to oral contraceptives over this period of time was relatively small [27]. In addition, the availability of multiple concurrent population-based inception cohorts facilitates the use of case cohort designs, greatly augmenting statistical power in the observational epidemiology studies [95, 96]. This approach is being utilized in our current studies examining the risk of heart disease in RA.

REP facilitates studies with reduced risk of biases

Since the REP is based on a geographically defined population, it is not subject to the healthy beneficiary bias that may be encountered in managed-care systems, nor to the referral bias that may be present in registries based in tertiary-care hospitals and clinics. Indeed, there may be dramatic differences in the clinical spectrum and outcomes between referral patients and unselected community patients. Moreover, unlike US Medicare data, the REP data are not limited to persons aged ≥65 years, and the inclusion of the younger population is critical for investigating early vs mid-life determinants, outcomes and treatment of rheumatic diseases. For example, the REP-based cohort of JRA patients were followed up well into adulthood, and we were able to examine their BMD [50] and psychosocial status [48] in adulthood. Importantly, because medical record information is recorded at the time the disease or risk factor is observed, it is not subject to the potential recall biases present in self-reported data [97].

The REP also facilitates studies minimizing incidence-prevalence bias. Studies based on prevalence series include patients of varying disease duration and exclude those who died early of the condition. In contrast, the REP resources afford identification and follow-up of incident series that reflect the full range of disease severity and mortality. This was strikingly evident in a mortality review in RA where the pooled standardized mortality ration from inception cohorts (both, community/population and clinic based) were much lower than those in non-inception cohorts [98]. The same is true for population-based rates of various types of infections in RA patients, which are difficult to obtain in clinic-based settings and frequently cited as background rates [17]. Finally, the REP studies are able to reduce non-participation bias. Due to the passive access to medical record data for virtually the complete population, the samples of study participants obtained using the REP are frequently more representative of the general population than samples of subjects who participate actively in a study [99]. This may be particularly important in studies evaluating treatment effectiveness and safety.

Use of electronic medical records for ascertainment and monitoring of the anti-rheumatic treatment and safety surveillance: biologics as an example

In recent years, traditional technologies of data processing at the Mayo Clinic (i.e. manual data abstraction from medical records) have been enhanced by a variety of tools, in particular, natural language processing (NLP). These tools allow free text in the electronic medical system to be indexed, searched, retrieved and analysed using state-of-the-art computer science techniques. Electronic medical records (EMRs) coupled with NLP provide the unique capability for data mining within the REP resources.

The clinical Text Analysis and Knowledge Extraction System (cTAKES) is a pipeline that was developed at the Mayo Clinic and was released as an open source at www.ohnlp.org. The cTAKES processes clinical notes and identifies the following clinical named entities: drugs, diseases/disorders, signs/symptoms, anatomical sites and procedures. Each discovered named entity is assigned attributes for the text span, the ontology mapping code, the context (family history, current, unrelated to patient) and a negation indicator. For example, in the sentence ‘No evidence of unstable angina’, unstable angina is discovered as a named entity of type disease/disorder, the text attribute is populated with the spanned value, the associated code gets a value of 4 557 003 for a systematized nomenclature of medicine-clinical terms (SNOMED_CT) match, the status is assigned the value of ‘current’, and negation is set to true.

These capabilities have already been applied to musculoskeletal and cardiovascular research, where unstructured text of the EMR was analysed to identify patients with RA. Although case ascertainment for most studies is currently performed mainly by manual data abstraction from paper or electronic clinical reports, the increasing adoption of the EMR makes it possible to analyse the unstructured text of clinical reports in ways that were historically impossible or cost prohibitive with paper-based records. A number of projects conducted using the Mayo Clinic EMR system have also shown the advantages of free text over US international classification of disease-9 disease billing codes for case identification. In addition, these new capabilities will expedite the process of obtaining health outcomes. By first identifying potential health states, this new information technology will lessen the burden and expense associated with manual records review and data abstraction. Furthermore, risk factors such as smoking status [100] and alcohol use can be automatically extracted from each patient’s medical records.

EMR-based systems empowered with NLP/text mining applications have been shown to efficiently identify and monitor cohorts of drug-exposed subjects over extended periods. For instance, we have shown the usefulness of EMR for safety surveillance using biologics as an example [101]. This system can also be useful for non-specific outcomes, such as signs and symptoms that are not coded and cannot be identified in administrative databases. This information analysed in context of the medication use can serve for monitoring of the treatment effectiveness and safety surveillance. Clinical notes can be analysed for positive and negative evidence, as well as for the degree of probability of signs and symptoms, thus providing accurate identification of medical status. These data can be supplemented with detailed information on medical history and clinical characteristics.

Among the developing capabilities for information and data mining are: statistical classifiers (machine learning approaches); improved mapping from text to concepts in a standards-based ontology (e.g. SNOMED-CT); drugs and adverse outcomes; and disambiguation of term senses.

Together, these novel technologies for information extraction from the clinical narrative provide an opportunity for the effective use of the extensive resources of the REP medical records-linkage system for hypothesis generation and testing in clinical research and epidemiology. Richly annotated data across the EMR has the potential to unveil previously unexplored or rare patterns of association. Meystre et al. [102] provide an overview of the state-of-the-art of information extraction from the EMR.

Infrastructure for translational research

The REP also facilitates T2 and T3 translational studies [103]. The acquisition of human biospecimens and the subsequent cellular/molecular analysis of that tissue and the ability to link with phenotypic information are critical to early translational studies in rheumatic diseases. Since the beginning of the 20th century, the Mayo Clinic maintained a tissue repository. Paraffin blocks and sections from all biopsy, surgery and autopsy procedures are stored indefinitely and easily accessible. For example, by relying on autopsy material from this tissue repository, we were able to assess the extent and characteristics of coronary atherosclerosis in RA patients compared with controls [104]. A unique T2–T3 translational resource of the REP is the provider billing data for all the Olmsted County health-care providers. This resource captures ∼95% of all physician and hospital services provided to local residents dating back to 1987. Since this resource covers the entire Olmsted County population, it is possible to compare the costs for a cohort of persons with a particular disease with costs for persons unaffected by that disease or with costs for the general population. Several studies relied on this unique resource to demonstrate the direct medical, indirect medical and lifetime costs of RA; costs related to NSAIDs [105], costs of rheumatological care [15]; costs of osteoporotic fractures [106]; costs of OA [11, 55]; and cost of PMR [71].

Conclusions

The REP is a large, centralized medical data system including the lifetime health-care information of essentially all residents of the Olmsted County, MN, USA over the past five decades. The unique features of the REP provide unparalleled capabilities for the population-based research in rheumatic diseases. In particular, the resources of the REP enable the longitudinal population-based studies across the full spectrum of rheumatic diseases with long and complete follow-up regardless of health-care provider or insurance. This type of data resources will be particularly useful in the future for comparative effectiveness and patient centred outcomes research. These unique capabilities of the REP are continuously advanced with the novel technologies (particularly, of the data processing and translational research) providing the state-of-the-art research platform for epidemiological studies. The findings obtained through the REP significantly contribute to the overall knowledge of the epidemiology of rheumatic diseases and may provide guidance for other studies into the aetiology, outcomes and impact of rheumatic diseases. Thus, the REP can be viewed as an exemplar of the advanced and constantly improving research infrastructure, informing and guiding the epidemiological knowledge, particularly with regard to rheumatic disease.

Disclosure statement: The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Maradit Kremers H, Crowson CS, Gabriel SE. Rochester Epidemiology Project: a unique resource for research in the rheumatic diseases. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2004;30:819–34. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Linos A, Worthington JW, O’Fallon W, Fuster V, Whisnant JP, Kurland LT. Effect of aspirin on prevention of coronary and cerebrovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. A long-term follow-up study. Mayo Clin Proc. 1978;53:581–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linos A, Worthington JW, Palumbo PJ, O’Fallon WM, Kurland LT. Occurrence of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and diabetes mellitus in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Chron Dis. 1980;33:73–7. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(80)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Linos A, Worthington JW, O’Fallon WM, Kurland LT. The epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis in Rochester, Minnesota: a study of incidence, prevalence, and mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 1980;111:87–98. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linos A, Worthington JW, O’Fallon WM, Kurland LT. Case-control study of rheumatoid arthritis and prior use of oral contraceptives. Lancet. 1983;1:1299–300. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)92413-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurland LT, Molgaard CA, Kurland EM, Erdtmann FJ, Stebbing GET. Lack of association of swine flu vaccine and rheumatoid arthritis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1984;59:816–21. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)65615-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hooyman JR, Melton LJ, 3rd, Nelson AM, O’Fallon WM, Riggs BL. Fractures after rheumatoid arthritis. A population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:1353–61. doi: 10.1002/art.1780271205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.del Junco DJ, Annegers JF, Luthra HS, Coulam CB, Kurland LT. Do oral contraceptives prevent rheumatoid arthritis? J Am Med Assoc. 1985;254:1938–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linos AD, O’Fallon WM, Worthington JW, Kurland LT. The effect of tonsillectomy and appendectomy on the development of rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1986;13:707–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gabriel SE. The sensitivity and specificity of computerized data bases for the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37:821–3. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, Campion ME, O’Fallon WM. Indirect and nonmedical costs among people with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis compared with nonarthritic controls. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:43–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, Luthra HS, Wagner JL, O’Fallon WM. Modeling the lifetime costs of rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:1269–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM. The epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis in Rochester, MN, 1955–1985. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:415–20. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199904)42:3<415::AID-ANR4>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: have we made an impact in 4 decades? [see comments] J Rheumatol. 1999;26:2529–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gabriel SE. Is rheumatoid arthritis care more costly when provided by rheumatologists compared with generalists? Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:1504–14. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200107)44:7<1504::AID-ART272>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doran MF, Pond GR, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. Trends in incidence and mortality in rheumatoid arthritis in Rochester, Minnesota, over a forty-year period. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:625–31. doi: 10.1002/art.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doran M, Crowson CS, Pond G, O’Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. Frequency of infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared with controls: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2287–93. doi: 10.1002/art.10524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doran M, Crowson CS, Pond G, O’Fallon W, Gabriel SE. Predictors of infection in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2294–300. doi: 10.1002/art.10529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turesson C, O’Fallon WM, Crowson CS, Gabriel SE, Matteson EL. Occurrence of extraarticular disease manifestations is associated with excess mortality in a community based cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:62–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turesson C, O’Fallon WM, Crowson CS, Gabriel SE, Matteson EL. Extra-articular disease manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis: incidence trends and risk factors over 46 years. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:722–7. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.8.722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turesson C, O’Fallon WM, Crowson CS, Gabriel SE, Matteson EL. No decrease over time in the incidence of extra-articular disease manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis - results from a community-based study of patients diagnosed during a 40-year period. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(Suppl.):S247. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maradit, Kremers H, Nicola P, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. Therapeutic strategies in rheumatoid arthritis over a 40-year period. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:2366–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warrington KJ, Kent PD, Frye RL, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis is an independent risk factor for multi-vessel coronary artery disease: a case control study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R984–91. doi: 10.1186/ar1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, Maradit, Kremers H, et al. Survival in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based analysis of trends over 40 years. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:54–8. doi: 10.1002/art.10705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maradit, Kremers HM, Bidaut-Russell M, Scott CG, Reinalda MS, Zinsmeister AR, Gabriel SE. Preventive medical services among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:1940–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aubry MC, Riehle DL, Edwards WD, et al. B-lymphocytes in plaque and adventitia of coronary arteries in two patients with rheumatoid arthritis and coronary atherosclerosis: preliminary observations. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2004;13:233–6. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Doran MF, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. The effect of oral contraceptives and estrogen replacement therapy on the risk of rheumatoid arthritis: a population based study. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:207–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maradit, Kremers H, Crowson CS, Nicola PJ, Ballman KV, Gabriel SE. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and congestive heart failure (CHF) in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [Abstract] Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:S557–8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maradit, Kremers H, Nicola PJ, Crowson CS, Ballman KV, Gabriel SE. Prognostic importance of low body mass index in relation to cardiovascular mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3450–7. doi: 10.1002/art.20612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crowson CS, Nicola PJ, Kremers H, et al. How much of the increased incidence of heart failure in rheumatoid arthritis is attributable to traditional cardiovascular risk factors and ischemic heart disease? Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3039–44. doi: 10.1002/art.21349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davis JM 3rd, Maradit, Kremers H, Gabriel SE. Use of low-dose glucocorticoids and the risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: what is the true direction of effect. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1856–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gonzalez A, Maradit, Kremers H, Crowson CS, Gabriel SE. Survival trends and risk factors for mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Adv Rheumatol. 2005;3:38–46. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maradit-Kremers H, Crowson CS, Nicola PJ, et al. Increased unrecognized coronary heart disease and sudden deaths in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:402–11. doi: 10.1002/art.20853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maradit-Kremers H, Nicola PJ, Crowson CS, Ballman KV, Gabriel SE. Cardiovascular death in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:722–32. doi: 10.1002/art.20878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nicola PJ, Maradit-Kremers H, Roger VL, et al. The risk of congestive heart failure in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study over 46 years. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:412–20. doi: 10.1002/art.20855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maradit, Kremers H, Nicola PJ, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. Patient, disease, and therapy-related factors that influence discontinuation of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: a population-based incidence cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:248–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maradit-Kremers H, Nicola PJ, Crowson CS, et al. Raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate signals heart failure in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:76–80. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.053710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nicola PJ, Crowson CS, Maradit-Kremers H, et al. Contribution of congestive heart failure and ischemic heart disease to excess mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:60–7. doi: 10.1002/art.21560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maradit-Kremers H, Nicola PJ, Crowson CS, et al. Raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate signals heart failure in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:76–80. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.053710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis JM, 3rd, Maradit, Kremers H, Crowson CS, et al. Glucocorticoids and cardiovascular events in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:820–30. doi: 10.1002/art.22418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davis JM, 3rd, Roger VL, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, Therneau TM, Gabriel SE. The presentation and outcome of heart failure in patients with rheumatoid arthritis differs from that in the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2603–11. doi: 10.1002/art.23798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gonzalez A, Icen M, Kremers HM, et al. Mortality trends in rheumatoid arthritis: the role of rheumatoid factor. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:1009–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gonzalez A, Maradit, Kremers HM, Crowson CS, et al. Do cardiovascular risk factors confer the same risk for cardiovascular outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis patients as in non-rheumatoid arthritis patients? Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:64–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.059980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kremers HM, Crowson CS, Therneau TM, Roger VL, Gabriel SE. High ten-year risk of cardiovascular disease in newly diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis patients: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2268–74. doi: 10.1002/art.23650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Towner SR, Michet CJ, Jr, O’Fallon WM, Nelson AM. The epidemiology of juvenile arthritis in Rochester, Minnesota 1960-1979. Arthritis Rheum. 1983;26:1208–13. doi: 10.1002/art.1780261006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peterson LS, Mason T, Nelson AM, O’Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis in Rochester, Minnesota 1960-1993. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:1385–90. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peterson LS, Mason T, Nelson AM, O’Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis in Rochester, Minnesota 1960-1993. Is the incidence decreasing? Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:S195. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peterson LS, Mason T, Nelson AM, O’Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. Psychosocial outcomes and health status of adults who have had juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: a controlled, population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:2235–40. doi: 10.1002/art.1780401219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.French AR, Mason T, Nelson AM, O’Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. Increased mortality in adults with a history of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:523–7. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200103)44:3<523::AID-ANR99>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.French AR, Mason T, Nelson AM, et al. Osteopenia in adults with a history of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. A population based study. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:1065–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shbeeb M, Uramoto KM, Gibson LE, O’Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. The epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, USA, 1982–1991. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:1247–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thumboo J, Uramoto K, Shbeeb MI, et al. Risk factors for the development of psoriatic arthritis: a population based nested case control study. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:757–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilson FC, Icen M, Crowson CS, McEvoy MT, Gabriel SE, Kremers HM. Time trends in epidemiology and characteristics of psoriatic arthritis over 3 decades: a population-based study. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:361–7. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wilson FC, Icen M, Crowson CS, McEvoy MT, Gabriel SE, Kremers HM. Incidence and clinical predictors of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:233–9. doi: 10.1002/art.24172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM. Costs of osteoarthritis: estimates from a geographically-defined population. J Rheumatol. 1995;22(Suppl. 43):23–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uramoto K, Shbeeb M, Sunku J, et al. Trends in the incidence and mortality of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) - 1950–1992. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:S214. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199901)42:1<46::AID-ANR6>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Salvarani C, Gabriel SE, O’Fallon WM, Hunder GG. The incidence of giant cell arteritis in Olmsted County, Minnesota: apparent fluctuations in a cyclic pattern. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:192–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-3-199508010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Evans JM, O’Fallon WM, Hunder GG. Increased incidence of aortic aneurysm and dissection in giant cell (temporal) arteritis. A population-based study. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:502–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-7-199504010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Icen M, Nicola PJ, Maradit-Kremers H, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus features in rheumatoid arthritis and their effect on overall mortality. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:50–7. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Salvarani C, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM, Hunder GG, Gabriel SE. Reappraisal of the epidemiology of giant cell arteritis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, over a fifty-year period. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:264–8. doi: 10.1002/art.20227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gabriel SE, O’Fallon WM, Achkar AA, Lie JT, Hunder GG. The use of clinical characteristics to predict the results of temporal artery biopsy among patients with suspected giant cell arteritis. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:93–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gabriel SE, Espy M, Erdman DD, Bjornsson J, Smith TF, Hunder GG. The role of parvovirus B19 in the pathogeneisis of giant cell arteritis: a preliminary evaluation. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1255–8. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199906)42:6<1255::AID-ANR23>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Proven A, Gabriel SE, Orces C, O’Fallon WM, Hunder GG. Glucocorticoid therapy in giant cell arteritis: duration and adverse outcomes. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:703–8. doi: 10.1002/art.11388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Achkar AA, Lie JT, Hunder GG, O’Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. How does previous corticosteroid treatment affect the biopsy findings in giant cell (temporal) arteritis? Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:987–92. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-120-12-199406150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Salvarani C, Gabriel SE, O’Fallon WM, Hunder GG. Epidemiology of polymyalgia rheumatica in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1970–1991. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:369–73. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gabriel SE, Sunku J, Salvarani C, O’Fallon WM, Hunder GG. Adverse outcomes of anti-inflammatory therapy among patients with polymyalgia rheumatica. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1873–8. doi: 10.1002/art.1780401022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Proven A, Gabriel SE, O’Fallon WM, Hunder GG. Polymyalgia rheumatica with low erythrocyte sedimentation rate at diagnosis. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:1333–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Doran MF, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM, Hunder GG, Gabriel SE. Trends in the incidence of polymyalgia rheumatica over a 30 year period in Olmsted County, Minnesota, USA. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:1694–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Maradit, Kremers H, Reinalda MS, Crowson CS, Zinsmeister AR, Hunder GG, Gabriel SE. Use of physician services in a population-based cohort of patients with polymyalgia rheumatica over the course of their disease. Arthritis Care Res. 2005;53:395–403. doi: 10.1002/art.21160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Maradit, Kremers H, Reinalda MS, Crowson CS, Zinsmeister AR, Hunder GG, Gabriel SE. Relapse in a population based cohort of patients with polymyalgia rheumatica. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:65–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kremers HM, Reinalda MS, Crowson CS, Zinsmeister AR, Hunder GG, Gabriel SE. Direct medical costs of polymyalgia rheumatica. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:578–84. doi: 10.1002/art.21311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maradit, Kremers H, Reinalda MS, Crowson CS, Davis JM 3rd, Hunder G, Gabriel SE. Glucocorticoids and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in polymyalgia rheumatica. Arthritis Care Res. 2006;57:279–86. doi: 10.1002/art.22548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.O’Duffy JD, Hunder GG, Kelly PJ. Decreasing prevalence of tophaceous gout. Mayo Clin Proc. 1975;50:227–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Arromdee E, Michet CJ, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. Epidemiology of gout: is the incidence rising? J Rheumatol. 2002;29:2403–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pillemer SR, Matteson EL, Jacobsson LT, et al. Incidence of physician-diagnosed primary Sjogren syndrome in residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:593–9. doi: 10.4065/76.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Calamia KT, Wilson FC, Icen M, Crowson CS, Gabriel SE, Kremers HM. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of Behcet’s disease in the US: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:600–4. doi: 10.1002/art.24423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Carbone LD, Cooper C, Michet CJ, Atkinson EJ, O’Fallon WM, Melton LJ., 3rd Ankylosing spondylitis in Rochester, Minnesota, 1935–1989. Is the epidemiology changing? Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:1476–82. doi: 10.1002/art.1780351211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bucciarelli S, Espinosa G, Cervera R. The CAPS Registry: morbidity and mortality of the catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. Lupus. 2009;18:905–12. doi: 10.1177/0961203309106833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Svensson B, Holmstrom G, Lindqvist U. Development and early experiences of a Swedish psoriatic arthritis register. Scand J Rheumatol. 2002;31:221–5. doi: 10.1080/030097402320318413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kremer JM. The CORRONA database. Autoimmun Rev. 2006;5:46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pope D, Croft P. Surveys using general practice registers: who are the non-responders? J Public Health Med. 1996;18:6–12. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a024464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kamal KM, Madhavan SS, Hornsby JA, Miller LA, Kavookjian J, Scott V. Use of tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in rheumatoid arthritis: a national survey of practicing United States rheumatologists. Joint Bone Spine. 2006;73:718–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rupp I, Triemstra M, Boshuizen HC, Jacobi CE, Dinant HJ, van den Bos GA. Selection bias due to non-response in a health survey among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Public Health. 2002;12:131–5. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/12.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Carpenter WR, Weiner BJ, Kaluzny AD, Domino ME, Lee SY. The effects of managed care and competition on community-based clinical research. Med Care. 2006;44:671–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000220269.65196.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wood SD. Strategies for improving health plan member retention. Healthc Financ Manage. 1999;(Suppl.):1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schneeweiss S, Avorn J. A review of uses of health care utilization databases for epidemiologic research on therapeutics. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:323–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fisher ES, Baron JA, Malenka DJ, Barrett J, Bubolz TA. Overcoming potential pitfalls in the use of Medicare data for epidemiologic research. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:1487–90. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.12.1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Katz JN, Barrett J, Liang MH, et al. Sensitivity and positive predictive value of Medicare part B physician claims for rheumatologic diagnoses and procedures. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1594–600. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Newcombe HB. Handbook of record linkage: methods for health and statistical studies, administration, and business. Oxford (Oxfordshire): New York Oxford University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Porta MS. International epidemiological association. A dictionary of epidemiology. 5th edition. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Liang KP, Kremers HM, Crowson CS, et al. Autoantibodies and the risk of cardiovascular events. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:2462–9. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.da Silva E, Doran MF, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM, Matteson EL. Declining use of orthopedic surgery in patients with rheumatoid arthritis? Results of a long-term, population-based assessment. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;49:216–20. doi: 10.1002/art.10998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Crowson CS, Therneau TM, O’Fallon WM. Attributable risk estimation in cohort studies. Technical Report #82. Rochester, MN: Mayo Clinic, Department of Health Sciences Research; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Prentice RL. A case-cohort design for epidemiologic cohort studies and disease prevention trials. Biometrika. 1986;73:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Barlow WE, Ichikawa L, Rosner D, Izumi S. Analysis of case-cohort designs. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:1165–72. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00102-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Beard CM, Melton LJ, 3rd, Cedel SL, Richelson LS, Riggs BL. Ascertainment of risk factors for osteoporosis: comparison of interview data with medical record review. J Bone Miner Res. 1990;5:691–9. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650050705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sokka T, Abelson B, Pincus T. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis: 2008 update. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26(5 Suppl 5):S35–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Melton LJ, 3rd, Dyck PJ, Karnes JL, O’Brien PC, Service FJ. Non-response bias in studies of diabetic complications: the Rochester Diabetic Neuropathy Study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:341–8. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90148-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Savova GK, Ogren PV, Duffy PH, Buntrock JD, Chute CG. Mayo clinic NLP system for patient smoking status identification. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2008;15:25–8. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Maradit, Kremers H, Pakhomov SV, Crowson CS, Shah DN, Gabriel SE. Use of the electronic medical records for safety surveillance: biologics as an example [Abstract] Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:S284. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Meystre S, Savova G, Kipper-Schuler K, Hurdle J. Extracting information from textual documents in the electronic health record: a review of recent research. IMIA Yearb Med Inform. 2008:138–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dougherty D, Conway PH. The “3T’s” road map to transform US health care: the “how” of high-quality care. JAMA. 2008;299:2319–21. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.19.2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Aubry MC, Maradit-Kremers H, Reinalda MS, Crowson CS, Edwards WD, Gabriel SE. Differences in atherosclerotic coronary heart disease between subjects with and without rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:937–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Gabriel SE, Campion ME, O’Fallon WM, Melton LJ., III The health care costs of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-related gastric ulcer in Olmsted County, MN, 1987–1990. Post Market Surveill. 1992;6:135–46. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Melton LJ, 3rd, Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, Tosteson AN, Johnell O, Kanis JA. Cost-equivalence of different osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2003;14:383–8. doi: 10.1007/s00198-003-1385-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]