Abstract

Objective:

To assess evidence regarding periprocedural management of antithrombotic drugs in patients with ischemic cerebrovascular disease. The complete guideline on which this summary is based is available as an online data supplement to this article.

Methods:

Systematic literature review with practice recommendations.

Results and recommendations:

Clinicians managing antithrombotic medications periprocedurally must weigh bleeding risks from drug continuation against thromboembolic risks from discontinuation. Stroke patients undergoing dental procedures should routinely continue aspirin (Level A). Stroke patients undergoing invasive ocular anesthesia, cataract surgery, dermatologic procedures, transrectal ultrasound–guided prostate biopsy, spinal/epidural procedures, and carpal tunnel surgery should probably continue aspirin (Level B). Some stroke patients undergoing vitreoretinal surgery, EMG, transbronchial lung biopsy, colonoscopic polypectomy, upper endoscopy and biopsy/sphincterotomy, and abdominal ultrasound–guided biopsies should possibly continue aspirin (Level C). Stroke patients requiring warfarin should routinely continue it when undergoing dental procedures (Level A) and probably continue it for dermatologic procedures (Level B). Some patients undergoing EMG, prostate procedures, inguinal herniorrhaphy, and endothermal ablation of the great saphenous vein should possibly continue warfarin (Level C). Whereas neurologists should counsel that warfarin probably does not increase clinically important bleeding with ocular anesthesia (Level B), other ophthalmologic studies lack the statistical precision to make recommendations (Level U). Neurologists should counsel that warfarin might increase bleeding with colonoscopic polypectomy (Level C). There is insufficient evidence to support or refute periprocedural heparin bridging therapy to reduce thromboembolic events in chronically anticoagulated patients (Level U). Neurologists should counsel that bridging therapy is probably associated with increased bleeding risks as compared with warfarin cessation (Level B). The risk difference as compared with continuing warfarin is unknown (Level U).

Neurologists are frequently asked to recommend whether practitioners should temporarily stop anticoagulation (AC) and antiplatelet (AP) agents in patients with prior strokes or TIAs undergoing invasive procedures. The balance of risks of recurrent vascular events with discontinuation of these agents vs increased periprocedural bleeding with continuation is often unclear, leading to variability in care and possibly adverse outcomes.

This article summarizes the findings, conclusions, and recommendations of an evidence-based guideline regarding periprocedural management of patients with a history of ischemic cerebrovascular disease receiving AC or AP agents. The full text of the guideline is available as a data supplement on the Neurology® Web site at www.neurology.org. Four questions are addressed:

What is the thromboembolic (TE) risk of temporarily discontinuing an antithrombotic medication?

What are the perioperative bleeding risks of continuing antithrombotic agents?

If oral AC is stopped, should bridging therapy be used?

If an antithrombotic agent is stopped, what should be the timing of discontinuation?

DESCRIPTION OF THE ANALYTIC PROCESS

The American Academy of Neurology Guideline Development Subcommittee (see appendices e-1 and e-2) convened an expert panel to develop the guideline. Literature searches of MEDLINE and EMBASE through August 2011 were performed (see appendices e-3 and e-4). The searches identified 5,904 citations yielding 133 relevant articles, which were rated for their risk of bias (see appendix e-5), and recommendations were made that were linked to the evidence (see appendix e-6).

Articles were included if they studied patients taking oral antithrombotic agents for primary or secondary cardiovascular disease or stroke prevention (including articles relating to atrial fibrillation), studied at least 20 subjects, included a comparison group, assessed risks of continuing or discontinuing an agent, and clearly described interventions and outcome measures. Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular procedures were excluded because of confounding issues. Bleeding was classified according to GUSTO criteria.1 Moderate or severe bleeding was considered clinically important. All studies are presented in the evidence table (table e-1), including Class III studies that did not inform recommendations.

ANALYSIS OF EVIDENCE

What is the TE risk of temporarily discontinuing AP agents?

Based on one Class I study1 and 2 Class II studies2,3 that addressed TE risks of temporarily discontinuing AP agents, aspirin discontinuation is probably associated with increased stroke or TIA risk. Estimated stroke risk varies with the duration of aspirin discontinuation: relative risk (RR) was 1.97 for 2 weeks, odds ratio was 3.4 for 4 weeks, and RR was 1.40 for 5 months (one Class II study each).

What is the TE risk of temporarily discontinuing AC?

Studies of AC discontinuation enroll subjects with various AC indications, each with different TE risks. No studies meeting inclusion criteria with sufficient sample size to support conclusions compared TE risks in subjects continuing warfarin with those discontinuing warfarin (with or without periprocedural heparin bridging). One Class I study4 found that the TE event risk of warfarin discontinuation is probably higher if AC is stopped for ≥7 days (RR 5.5, 95% confidence interval 1.2–24.2) (one Class I study).

What are the perioperative bleeding risks of continuing antithrombotic agents?

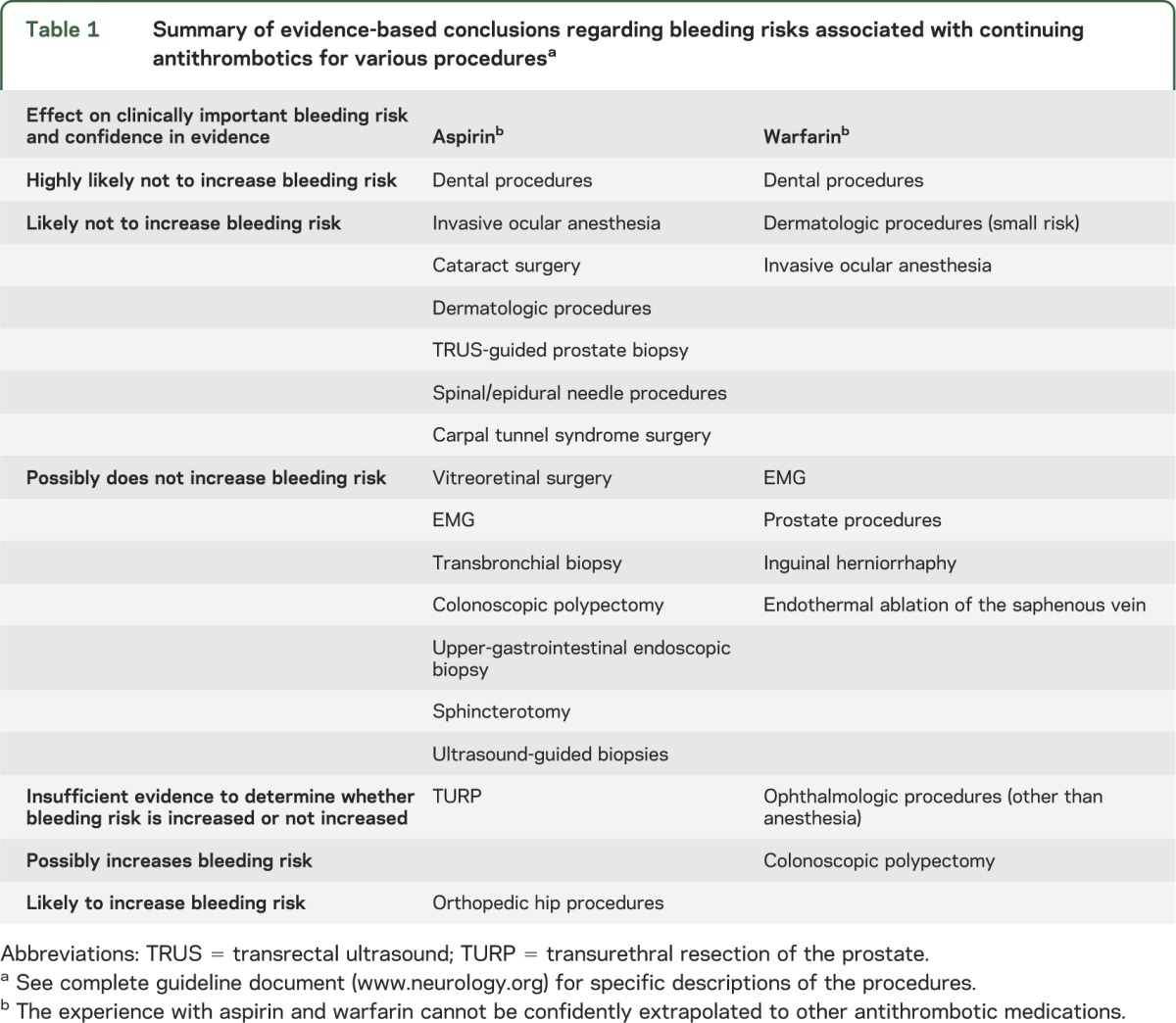

Table 1 summarizes the evidence-based conclusions developed from the systematic review of the literature. Only procedures for which we found evidence appear in table 1. For specific details, including quantitative descriptions of risks, refer to the full guideline document (www.neurology.org).

Table 1.

Summary of evidence-based conclusions regarding bleeding risks associated with continuing antithrombotics for various proceduresa

If oral AC is stopped, should bridging therapy be used?

There is insufficient evidence to support or refute a difference in TE events when heparin bridging is used (vs discontinuation of oral AC without bridging); however, most studies suggest that heparin bridging is probably associated with an increased risk of periprocedural bleeding in general (2 Class I studies, one Class II study, and one Class III study showing increased risk, with one additional Class I study showing no substantial increased risk).

There is insufficient evidence to support or refute differences in TE risk between management strategies of continuing oral AC vs heparin bridging. One Class I study found that the risk of bleeding is probably similar between low-molecular-weight heparin bridging and AC continuation in dental procedures.

If an antithrombotic agent is stopped, what should be the timing of discontinuation?

Data are insufficient to support any conclusions.

CLINICAL CONTEXT

The antithrombotic effect duration of aspirin and clopidogrel is estimated to be 7 days.5 The duration of action of a single dose of warfarin is estimated at 2 to 5 days.5 Hence, to reverse the antithrombotic effect, it is generally recommended that AP agents be stopped 7 to 10 days, and warfarin 5 days, preprocedure.6 Shorter discontinuation periods were used in many of the reviewed studies.

Stopping antithrombotics increases the risk of TE events. The exact magnitude of this risk increase is unknown. To minimize this risk, it seems reasonable to minimize the duration of antithrombotic discontinuation.

When considering the risks and benefits of antithrombotic discontinuation, it is important to consider both the frequency of undesirable outcomes and their long-term consequences. TE events occur infrequently, but the associated morbidity and mortality rates are high. In contrast, most reported bleeding outcomes are relatively mild. Decisions regarding periprocedural antithrombotic therapy depend on weighing these competing risks in the context of individual patient characteristics.

Patient preferences must inform these risk–benefit judgments. In a study comparing preferences of patients with atrial fibrillation with those of physicians, patients were willing to experience a mean of 17.4 excess-bleeding events with warfarin and 14.7 excess-bleeding events with aspirin to prevent a stroke.7 Sample clinical scenarios for guideline application are presented in appendix 1.

RECOMMENDATIONS

It is axiomatic that clinicians managing antithrombotic medications periprocedurally weigh bleeding risks from drug continuation against TE risks from discontinuation at the individual patient level, although high-quality evidence on which to base this decision is often unavailable. In addition, even when evidence is insufficient to exclude a difference in bleeding or shows a small increase in clinically important bleeding with antithrombotic agents, physicians may reasonably judge that the risks and morbidity of TE events exceed those associated with bleeding.

Neurologists should counsel both patients taking aspirin for secondary stroke prevention and their physicians that aspirin discontinuation is probably associated with increased stroke and TIA risk (Level B). Estimated stroke risks vary across studies and according to duration of aspirin discontinuation.

Neurologists should counsel patients taking AC for stroke prevention that the TE risks associated with different AC periprocedural management strategies (continuing oral AC or stopping it with or without bridging heparin) are unknown (Level U) but that the risk of TE complications with warfarin discontinuation is probably higher if AC is stopped for ≥7 days (Level B).

Patients taking aspirin should be counseled that aspirin continuation is highly unlikely to increase clinically important bleeding complications with dental procedures (Level A). Given minimal clinically important bleeding risks, it is reasonable that stroke patients undergoing dental procedures should routinely continue aspirin (Level A).

Patients taking aspirin should be counseled that aspirin continuation probably does not increase clinically important bleeding complications with invasive ocular anesthesia, cataract surgery, dermatologic procedures, transrectal ultrasound–guided prostate biopsy, spinal/epidural procedures, and carpal tunnel surgery (Level B). Given minimal clinically important bleeding risks, it is reasonable that stroke patients undergoing these procedures should probably continue aspirin (Level B).

Aspirin continuation might not increase clinically important bleeding in vitreoretinal surgery, EMG, transbronchial lung biopsy, colonoscopic polypectomy, upper endoscopy with biopsy, sphincterotomy, and abdominal ultrasound–guided biopsies. Given the weaker data supporting minimal clinically important bleeding risks, it is reasonable that some stroke patients undergoing these procedures should possibly continue aspirin (Level C).

Although bleeding events were rare, studies of transurethral resection of the prostate lack the statistical precision to exclude clinically important bleeding risks with aspirin continuation (Level U).

Patients taking aspirin should be counseled that aspirin probably increases bleeding risks during orthopedic hip procedures (Level B).

Neurologists should counsel patients that there is insufficient evidence to make recommendations regarding appropriate periprocedural clopidogrel, ticlopidine, or aspirin/dipyridamole management in most situations (Level U). Aspirin recommendations cannot be extrapolated with certainty to other AP agents.

Patients taking warfarin should be counseled that warfarin continuation is highly unlikely to be associated with increased clinically important bleeding complications with dental procedures (Level A). Given minimal bleeding risks, stroke patients undergoing dental procedures should routinely continue warfarin (Level A).

Patients taking warfarin should be counseled that warfarin continuation is probably associated with only a small (1.2%) increased risk difference for bleeding during dermatologic procedures on the basis of a meta-analysis of heterogeneous and conflicting studies (Level B). Thus, patients undergoing dermatologic procedures should probably continue warfarin (Level B).

Patients taking warfarin should be counseled that warfarin continuation is probably not associated with an increased risk of clinically important bleeding with ocular anesthesia (Level B). However, AC practices during ophthalmologic procedures may be driven by the postanesthesia procedure. Although bleeding events were rare, ophthalmologic studies (other than those regarding ocular anesthesia) lack the statistical precision to exclude clinically important bleeding risks with warfarin continuation. Thus, there is insufficient evidence to make practice recommendations regarding warfarin discontinuation in ophthalmologic procedures (Level U).

Warfarin might be associated with no increased clinically important bleeding with EMG, prostate procedures, inguinal herniorrhaphy, and endothermal ablation of the great saphenous vein. Thus, patients undergoing these procedures should possibly continue warfarin (Level C).

Patients taking warfarin should be counseled that warfarin continuation might increase bleeding with colonoscopic polypectomy (Level C). Thus, patients undergoing this procedure should possibly temporarily discontinue warfarin (Level C).

Neurologists should counsel patients that there is insufficient evidence to make recommendations regarding appropriate periprocedural management of nonwarfarin oral AC (Level U). Warfarin recommendations cannot be extrapolated with certainty to other AC agents.

There is insufficient evidence to determine differences in TE in chronically anticoagulated patients managed with heparin bridging therapy relative to oral AC discontinuation or continuation. Patients taking warfarin should be counseled that bridging therapy is probably associated with increased bleeding risks in procedures in general relative to AC cessation (Level B). Bridging probably does not reduce clinically important bleeding relative to continued AC with warfarin in dentistry, but bleeding risk differences between patients managed with continued warfarin vs bridging therapy in other procedures are unknown. Given that the benefits of bridging therapy are not established and that bridging is probably associated with increased bleeding risks, there is insufficient evidence to support or refute bridging therapy use in general (Level U).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Thomas S.D. Getchius and Erin Hagen for support during guideline development and Stanley N. Cohen, MD, and Cathy Sila, MD, for assistance with abstract review in early guideline development.

GLOSSARY

- AC

anticoagulation

- AP

antiplatelet

- RR

relative risk

- TE

thromboembolic

Appendix 1. Sample clinical scenarios for guideline application.

Clinical scenario 1: Patient A is a 65-year-old man with a history of hypertension and hypercholesterolemia who had a stroke 1 year ago attributed to intracranial large-artery atherosclerosis. He has mild residual left hemiparesis, and his secondary stroke prevention therapy includes risk factor control and aspirin 325 mg daily. He is due for routine colonoscopy screening. His neurologist reviews the guideline and assesses that the patient's risk for recurrent stroke includes his known intracranial large-artery atherosclerotic event. Given that the patient may not need polypectomy with his colonoscopy, that the risk difference for bleeding with polypectomy associated with aspirin is approximately 2.0%, and that bleeding with polypectomy is likely to have lower morbidity risk than recurrent stroke risk, the neurologist recommends that aspirin be continued pericolonoscopy and obtains the opinions of both the patient and his gastrointestinal physician. The patient wants to have his colonoscopy, as his cousin was recently diagnosed with colon cancer, and is willing to accept an increased bleeding risk to avoid recurrent stroke. Thus, he proceeds with colonoscopy and possible polypectomy while continuing aspirin 325 mg daily.

Clinical scenario 2: Patient B is a 70-year-old woman who had a small-vessel distribution ischemic stroke associated with uncontrolled hypertension 5 years previously. She has no residual deficits and has been diligent in controlling her vascular risk factors. She has recently been diagnosed with breast cancer requiring mastectomy. Her neurologist reviews the guideline and notes that there is minimal literature for the risks associated with more invasive procedures. The neurologist counsels the patient and her oncologist that the patient likely has a relatively low risk of recurrent stroke with brief aspirin cessation and that there is little research on bleeding risks with aspirin during invasive procedures. Together, they choose to stop the aspirin 7 days before the surgery and restart it the day after the surgery. The importance of restarting the aspirin postoperatively is stressed, and a specific start date is provided to the patient.

Clinical scenario 3: Patient C is a 60-year-old man with chronic atrial fibrillation and prior cardioembolic stroke treated with chronic warfarin. He is the primary caregiver for his wife with Alzheimer disease, but his cataracts have worsened to the degree that surgery is needed for him to continue to care for her and drive her to appointments. The patient's neurologist reviews the guideline and finds that the risks associated with warfarin during ophthalmologic procedures have not been established with sufficient precision. The patient feels strongly, however, that he would rather tolerate the chance of increased bleeding complications than risk a recurrent cardioembolic stroke that might impair his ability to care for his wife. Given the risk–benefit ratio and patient preference, the ophthalmologist, neurologist, and patient decide to continue warfarin during the cataract surgery.

Footnotes

Supplemental data at www.neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Melissa J. Armstrong: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, acquisition of data, statistical analysis. Gary Gronseth: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data. David C. Anderson: drafting/revising the manuscript, acquisition of data. José Biller: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, acquisition of data, statistical analysis, study supervision. Brett Cucchiara: drafting/revising the manuscript, analysis or interpretation of data. Rima Dafer: drafting/revising the manuscript, analysis or interpretation of data, acquisition of data, statistical analysis. Larry B. Goldstein: drafting/revising the manuscript, analysis or interpretation of data. Michael Schneck: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data. Steven R. Messé: drafting/revising the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data, study supervision.

STUDY FUNDING

This guideline was developed with financial support from the American Academy of Neurology. None of the authors received reimbursement, honoraria, or stipends for their participation in development of this guideline.

DISCLOSURE

M.J. Armstrong, G. Gronseth, D.C. Anderson, J. Biller, B. Cucchiara, R. Dafer, and L.B. Goldstein report no disclosures. M. Schneck has participated in the past 2 years as a local principal investigator for multicenter trials sponsored by the NIH, Lundbeck Pharmaceuticals, Brigham & Women's/Schering Plough (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction consortium), Gore Inc., and NMT Medical. He is currently working on an investigator-initiated project to be supported by Baxter, Inc. He has served on speakers' bureaus for Boehringer-Ingelheim and Bristol-Myers Sanofi (none in past 2 years); has received an honorarium from the American Academy of Neurology Continuum project, from UpToDate.com, and from various continuing medical education lectures; and has participated in expert testimony for medical malpractice cases. He has no significant stock or other financial conflicts of interest. S.R. Messé has received royalties for articles on antithrombotics and stroke published on www.UpToDate.com. He has also received research support from the NIH for a study of the pharmacogenomics of warfarin and a study to evaluate neurologic outcomes from surgery. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

DISCLAIMER

This statement is provided as an educational service of the American Academy of Neurology. It is based on an assessment of current scientific and clinical information. It is not intended to include all possible proper methods of care for a particular neurologic problem or all legitimate criteria for choosing to use a specific procedure. Neither is it intended to exclude any reasonable alternative methodologies. The AAN recognizes that specific patient care decisions are the prerogative of the patient and the physician caring for the patient, based on all of the circumstances involved. The clinical context section is made available in order to place the evidence-based guideline(s) into perspective with current practice habits and challenges. Formal practice recommendations are not intended to replace clinical judgment.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The American Academy of Neurology is committed to producing independent, critical, and truthful clinical practice guidelines (CPGs). Significant efforts are made to minimize the potential for conflicts of interest to influence the recommendations of this CPG. To the extent possible, the AAN keeps separate those who have a financial stake in the success or failure of the products appraised in the CPGs and the developers of the guidelines. Conflict of interest forms were obtained from all authors and reviewed by an oversight committee prior to project initiation. AAN limits the participation of authors with substantial conflicts of interest. The AAN forbids commercial participation in, or funding of, guideline projects. Drafts of the guideline have been reviewed by at least 3 AAN committees, a network of neurologists, Neurology® peer reviewers, and representatives from related fields. The AAN Guideline Author Conflict of Interest Policy can be viewed at www.aan.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Oscarsson A, Gupta A, Fredrikson M, et al. To continue or discontinue aspirin in the perioperative period: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Br J Anaesth 2010;104:305–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maulaz AB, Bezerra DC, Michel P, Bogousslavsky J. Effect of discontinuing aspirin therapy on the risk of brain ischemic stroke. Arch Neurol 2005;62:1217–1220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia Rodriguez LA, Cea Soriano L, Hill C, Johansson S. Increased risk of stroke after discontinuation of acetylsalicylic acid: a UK primary care study. Neurology 2011;76:740–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia DA, Regan S, Henault LE, et al. Risk of thromboembolism with short-term interruption of warfarin therapy. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:63–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Repchinsky C, ed. CPS 2009 Compendium of Pharmaceuticals and Specialties. Ottawa: Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Douketis JD, Berger PB, Dunn AS, et al. The perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th ed). Chest 2008;133:299S–339S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devereaux PJ, Anderson DR, Gardner MJ, et al. Differences between perspectives of physicians and patients on anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation: observational study. BMJ 2001;323:1218–1222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.