Abstract

Identifying impairments in the capacity to make and execute decisions is critical to the assessment and remediation of elder self-neglect. Few capacity assessment tools are available for use outside of health care settings and none have been validated in the context of elder self-neglect. Health and social services professionals are in need of validated tools to assess capacity for self-care and self protection during initial evaluations of older adults with suspected self-neglect syndrome. Currently, legal and medical declarations of incapacity and guardianship rely on clinical evaluations and instruments developed to assess only decision-making capacity. This paper first describes the conceptual and methodological challenges to assessing the capacity to make and execute decisions regarding safe and independent living. Second, the paper describes the pragmatic obstacles to developing a screening tool for the capacity for self-care and self protection (SC&P). Finally, the paper outlines the process for validation and field testing of the screening tool. A valid and feasible screening tool can then be used during field assessments by social services professionals to screen for potential impairments in the capacity for self-care and protection in vulnerable older adults.

Keywords: self-neglect syndrome, elder abuse and neglect, capacity, decision making

BACKGROUND

Self-neglect

Self-neglect can be defined as 1) the failure to engage in self-care acts that adequately regulate independent living or as 2) the failure to take actions to prevent conditions or situations that adversely affect the safety of oneself or others.1–3 In many cases, individuals display poor personal hygiene, receive poor nutrition, live in squalor with garbage or spoiled food, and have poor adherence to their medical regimens.4 A predicate state of vulnerability from diminished capacity for self-care and self protection (SC&P) may be a common denominator among the various clinical phenotypes of chronic self-neglect;5 and incapacity for SC&P can also expose elders to numerous forms of abuse, medical morbidity, placement in long-term care, and even death.6–9

Older adults with physical disabilities are distinctly different from those who lack capacity for SC&P because the former identify and seek appropriate assistance to ensure their safety and independence. For example, some older adults who self-neglect refuse support and do not welcome interventions. Typically, disabled individuals with intact capacity for SC&P, on the other hand, actively seek and facilitate appropriate interventions.3 Legal and ethical conflicts arise when health and social services professionals face vulnerable older adults who refuse potentially efficacious interventions. In these cases, assessments regarding a person’s capacity to make decisions about their own health, safety, and independence (i.e., capacity for SC&P), and the appropriate role, if any, of health and social interventions to alleviate self-neglect are key considerations.

Conceptual Challenges

Contemporary medical law and ethics presume adult patients are competent (i.e., able to make decisions about their medical care). This assumption puts the burden on the clinician to determine whether the patient lacks autonomy to make medical decisions and on the courts to establish whether the patient lacks competence in cases of legal adjudication. An emphasis has been placed on what ethicists call a deontological approach to respect for patient autonomy. Therefore, respect for the patient’s self-determination is a key issue. Justification of such an action-guiding principle does not appeal to consequences but to other morally relevant considerations, such as human dignity, autonomy, and the sanctity of life. In the clinical setting, deontological constraints prevent clinicians from interfering with decisions of adult patients, even when these choices jeopardize the patient’s health or safety.

The ethical presumption of autonomy developed in the acute-care setting where the patient’s role is to authorize clinical interventions that healthcare professionals perform. Autonomy in this setting is justifiably conceptualized and assessed solely in terms of participation in medical decision-making (i.e., informed consent); however, in the chronic care setting, patients perform the routine care necessary to manage medical conditions over time. Conceptualizing and assessing autonomy in this setting solely in terms of decision-making capacity is inadequate and must be expanded to include both decisional and executive dimensions. Executive autonomy includes the ability to implement and adapt plans, especially when faced with both predictable and unexpected challenges.

When reliable evidence suggests that the autonomy to make or execute decisions may be impaired, clinicians are justified in temporarily overriding a patient’s “decisions” in order to stabilize him/her and comprehensively evaluate both dimensions of capacity. Even if subsequent evaluations determine that the individual’s ability to make decisions regarding his/her health and safety is largely intact, significant impairments in the ability to implement and adapt those decisions may exist. Limitations in the execution of medical decisions hinder overall autonomy since the individual’s intentions are not adequate for medical decisions.10 From both a deontological and consequentialist perspective,11 the individual’s autonomy, health, and safety are all at risk if either dimension (decisional or executive) is impaired.

Faden and Beauchamp’s theory of autonomous action includes both the decisional and executive dimensions.12 Ethical theories of autonomy are translated as the capacity to perform function(s), such as providing consent to medical procedures, managing one’s estate, and living safely and independently.11, 12 Among elders vulnerable to self-neglect, the ability to consider options and make choices may remain intact, while the ability to identify and extract oneself from harmful situations, circumstances, or relationships may be diminished. The key ethical and clinical considerations are whether these elders can make and implement decisions regarding their health, safety, and independence. Vulnerable elders are difficult to identify and diagnose because most retain communication and social skills and often make claims about their abilities that are inconsistent with actual performance.

Legally, the capacity for SC&P falls under State-level statutes for guardianship proceedings. When the courts deem an older adult to be an incapacitated person, which legally is “an adult individual who, because of a physical or mental condition, is substantially unable to provide food, clothing, or shelter for himself or herself, to care for the individual’s own health, or to manage the individual’s own financial affairs,”13 a guardian is appointed. From both legal and clinical perspectives, older adults who demonstrate incapacity with SC&P are vulnerable to self-neglect.

Prior Assessment Tools

Guardianship investigations and even legal standards of incompetence rely on field reports of social services professionals and formal evaluations by trained clinicians. This fact further emphasizes the importance of rigorously developed and validated screening instruments. Currently, legal and medical declarations of guardianship rely on clinical evaluations and instruments developed to assess only decision-making capacity.14–16 These instruments, such as the MacCAT-T,17 were originally designed to evaluate older adults with cognitive impairment who were being enrolled in research studies or considering invasive medical procedures. These evaluations focus predominantly on various dimensions of decision-making autonomy (e.g., understanding of relevant facts, appreciation of the personal consequences of a decision, and expression of a single choice that is free of external coercion).16

In the community setting, social services workers without validated instruments or training in neuropsychological methods are often charged with making judgments regarding an older adult’s capacity for SC&P. No formal standards specify these judgments, and many professionals simply determine whether the patient is oriented to person, place, or time. Capacity cannot be assessed or even screened during normal conversation.18, 19 Often, cognitively-impaired elders have preserved social function, and their words, although politely rendered, may not reflect an understanding of the issues at hand.

Recent studies have attempted to integrate capacity assessment methods within the context of community-living older adults. Cooney et al. described the challenges to the clinical assessment of capacity regarding the ability of older adults to choose to live independently in the community.20 These authors stressed the importance of evaluating an individual’s capacity to make decisions regarding everyday functional tasks. Lai and Karlawish have operationalized this model by developing a tool to evaluate decision-making capacity as it pertains to everyday decisions and conducted pilot testing of their tool with vulnerable older adults.21

The objectives of the current research agenda is to build from these prior studies to develop a tool that can screen for declines in the capacity to make and execute decisions regarding self-care and self protection in community-living older adults. Additional aims are to determine if this tool can be used effectively and efficiently by social services professionals during assessments of vulnerable elders outside of clinical settings, and to validate the tool prospectively as a screening instrument against the criterion standard of forensic evaluation.

PROPOSED METHODS

Screening Tool Structure

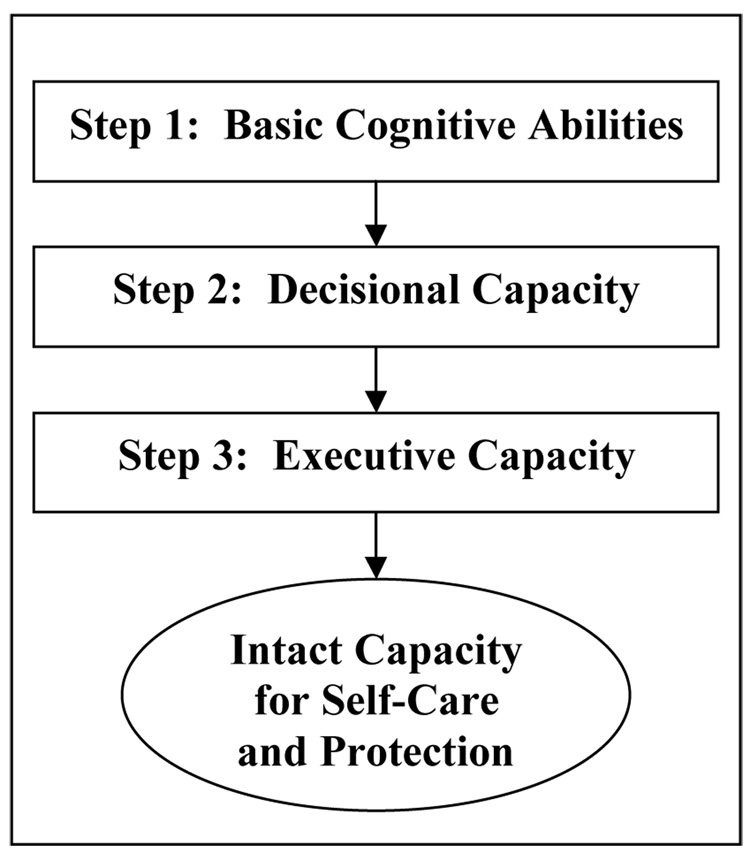

The structure of the screening tool should be driven by the conceptual issues raised previously. Figure 1 illustrates a proposed three-step structure to the screening tool design that parallels the three major conceptual domains of assessment: basic cognitive abilities, decision making capacity, and the capacity to execute decisions (execute capacity). Poor performance in any one domain is likely to warrant referral for need for additional testing with more comprehensive evaluations of capacity.

Figure 1.

Three-step screening method to identify persons at risk for loss of capacity for self-care and protection.

The basic cognitive ability assessment step will include three brief, validated tests of basic cognitive functions including attention, verbal language, and delayed recall. Scoring of the items will constitute a measurement “ceiling” that should, in practice, identify only the most cognitively-impaired older adults. Failure on any of these tests, therefore, would suggest significant deficits in basic cognitive ability and the need for more confirmatory, comprehensive capacity evaluation.

The assessment of decisional capacity will involve the use of one or more standardized case scenarios. The design of the case scenarios will be relevant to the decisions and meaningful to the persons being studied (i.e., functions related to the care and protection of oneself in daily activities).17 Scoring of the case scenarios will focus on established standards for evaluating decisions regarding everyday tasks: appreciation of problems, comparative reasoning, appreciation of harms, and consequential reasoning.21 Individuals will be assessed on their appreciation of current problems in their daily living, ability to compare different choices, appreciate harms related to those choices, and make decisions based on potential consequences.

The third step of the evaluation will assess executive capacity. Executive capacity consists of five domains of functioning related to self-care and protection. These domains include activities for personal care, activities for independent living, maintenance of the living environment, basic medical self-management, and activities related to daily financial affairs. When screening executive capacity, professionals will ask vulnerable elders to articulate if and how they perform particular activities associated with safe and independent living. The professional will also need to verify that the older adult can demonstrate performance of the activity. Disabilities or other physical limitations to performing SC&P domains should not affect executive capacity as long as the vulnerable older adult is aware of the limitations and cites potential surrogates or supports.

Integrating Conceptual and Methodology Issues

Validation of the screening tool is complicated by the necessity to integrate scientific, legal, and professional standards while maintaining methodological rigor required for instrument validation. In an effort to integrate these conceptual and methodological challenges, instrument development and validation must conform to the following criteria:

conform to the accepted theoretical and ethical construct of Autonomous Action, which is the foundation for informed consent;

is grounded in professionally defined, minimal standards for independent living (i.e., self-care) and personal and public safety (i.e., self-protection);

can be used in real-world settings and not only for research purposes;

demonstrates validity and reliability using rigorous psychometric methodology; and

includes feasibility and efficiency evaluations performed by local social services agencies and the probate court.

Meeting these complex and diverse validation criteria creates certain pragmatic obstacles to validity testing of the screening tool. Particular attention must be paid to both content validation and feasibility assessment. In fact, these additional validation steps are as critical in this case as the traditionally rigorous criterion validation that serves as the gold-standard for most screening instrument testing. Pragmatic obstacles to conducting these three validation phases are described below.

Phase 1—Content Validation

cognitive interviews22 with vulnerable elders known to have self-neglect syndrome and with comparable vulnerable elders with intact capacity for SC&P (defined by comprehensive geriatric assessment) can be performed to establish the content validity of the case scenarios used in the decisional capacity testing and functional domain testing used in the executive capacity step.

Phase 2—Testing for Instrument Feasibility

feasibility analysis of the screening tool should be performed in collaboration with potential users of the screening tool. Selected health care and social services professionals who evaluate vulnerable older adults can be trained in the purpose and use of the screening tool. Testing of the feasibility, efficiency, and validity of tool components and scoring can be done as the professional used the tool during field investigations of potential cases of self-neglect. Refinements to the screening tool can be made based on the results of these analyses.

Phase 3—Criterion Validation

prospective validation of the screening tool can be performed by having social services personnel use the screening tool during new evaluations of adults with self-neglect. Screening tool assessments would be scored against the criterion standard of an evaluation by a psychiatrist-led team. Standard epidemiological measures using diagnostic statistics (e.g., sensitivity, specificity, and interrater and intrarater reliability) would be used to establish the criterion validity of the screening tool.

DISCUSSION

Significance

Once developed and validated, this screening tool will be an important and effective instrument for evaluating capacity for self-care and protection in the setting of self-neglect. Since the lack of capacity for SC&P is essential to the definition of self-neglect, testing should be an integral component of any screening process used by social services professionals in field assessments. Evaluation by social services professionals, however, should be considered only as a screening process that suggests the potential for gaps in the capacity for SC&P. A positive result should not be considered definitive evidence that a patient has significant, irreversible loss of decisional or executive capacity; but should provide reliable clinical grounds for hypothesizing that the patient has such loss and the situation poses a threat to the health or safety of the elder or others. Screening tools do not provide diagnoses, and formal evaluation by trained clinicians should always occur as a consequence of a positive screening test. The results of using a reliable screening tool do, however, provide justification for further investigation of the subject’s condition.

A positive screening test may be used by a social services professional to suspend the automatic (deontological) assumption of capacity in a vulnerable elder. While the presumption of capacity is defeated, the ethical implications are limited. Thus, this positive result permits the profession to override a patient’s expressed decisions or preferences, to take the patient from his/her home or other community setting to the Emergency Department to be stabilized (as required by EMTALA), or to arrange for subsequent assessment by trained clinical personnel for formal evaluation of deficits in decisional and executive capacity. Any screening test of capacity, therefore, should be developed in concordance with legal and ethical principles, as well as rigorous psychometric and epidemiological methods.

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the significant strengths of this proposed project (rigorous development, feasibility testing, and validation), external validation on populations outside of Texas will be needed for full national implementation. Important variations in terms of geographical, socioeconomic, cultural, and educational variables between the different patient populations must be considered. In addition, the infrastructure of the healthcare system and the relationship between clinical and social services professionals may differ from those of CREST. To address these potential limitations, future studies to assess the external validity of the screening tool may be needed. Future research in this area and the clinical and social services professionals who evaluate and care for older adults with self-neglect will benefit directly from the development of this screening tool.

Discussant

Laurence B. McCullough, Ph.D., Professor of Medicine and Medical Ethics, in the Center for Medical Ethics and Health Policy, and Faculty Associate, Huffington Center on Aging, Baylor College of Medicine.

The proposed capacity screen has a very specific purpose, to suspend the presumption in both law and ethics that adult persons are competent and, therefore, may make their own decisions when the professionals suspect that they lack the capacity for self-care and protection. The unwillingness to suspend this presumption likely means that some patients will die or become seriously ill when these conditions could have been prevented.

Where does the presumption of competence in law and of capacity in ethics come from? These presumptions stem from the simple American belief that the state is a potential predator on our interests. In Canada and European countries, citizens view the state as a benign and even beneficent entity that understands our interests and will act consistently and effectively to protect them. The assumption that the state is a predator is not groundless or paranoia. The state has a long and sordid history of abusing its powers with the mentally ill through involuntary confinements that violated constitutional rights for decades. This practice was curbed by the courts and then finally by legislation. This bitter historical experience supports the wisdom of a public policy that insists on the presumption of competence and therefore sets high thresholds that must be satisfied in court to show that someone has lost competence. As a textbook example of deontological reasoning (justifying actions and policies for reasons of principle, independent of consequences), our courts and legislature have created public policy that protects our rights, including our right to act stupidly as judged by another.

Ethically, the situation is very different for clinicians. Clinicians are fiduciaries of patients. As such, clinicians are present to protect the health and lives of patients. Sometimes people must be protected from themselves when they exhibit impaired capacity to make decisions and to protect themselves. Doctors and nurses should, therefore, not be viewed as predators but as people who care about people. Indeed, the words “health care” are used for this very reason.

The screening tool is not designed to defeat or remove the presumption of competence in the law or capacity in ethics but to justifiably suspend the presumption for a short period of time. A failing score on the screening tool should be interpreted as providing to APS or EMS workers the authority to override the refusal of a clinical evaluation and treatment by someone who fails the screening tool and to proceed to the hospital for further evaluation. A failing score would not justify the APS or EMS personnel forcing treatment or making decisions for the individual. Such a score would, however, justify removing that individual (provided he or she did not physically resist to the point of making removal dangerous) out of circumstances of potential danger. The ethical justification for the screening tool is not simply paternalism, the view that someone else knows best what an individual’s interests should be and imposes a course of clinical management on the individual to pursue these interests. Rather, the ethical justification appeals to the fiduciary responsibility to protect and promote the health-related interests of individuals when it is very likely that the patient is unable to do so for himself or herself, because these interests are fundamental to the realization of other basic interests.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Mark Kunik for his insight and assistance and Sonora Hudson for her careful review and editing of a previous draft.

This work was supported by the Consortium for Research in Elder Self-Neglect (NIH grant P20-RR020626-03).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure(s):

Dr. Naik: Grant support: National Institute on Aging Career Development Award (5K23 AG 27144), Greenwall Foundation Bioethics Grant

--Speaker's forum or consultantships: Merck Vaccines

--Patents or financial holdings in health-related companies: None

Dr. Teal: Grant support: Efforts were supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (K01# DP-000090).

--Speaker's forum or consultantships: NONE

--Patents or financial holdings in health-related companies: NONE

Dr. Pavlik: Grant support: receives support from two NIH research grants (1R21 DK062098 (V. Pavlik, PI) and R01 HL-078589 (D. Hyman, PI). Neither of these grants was used to fund the research described in the present manuscript.

--Speaker's forum or consultantships: None

--Patents or financial holdings in health-related companies: None

Dr. Dyer: Grant support: Dr. Dyer acknowledges research support from NIH Grant# P20RR20626; Educational funding from Novartis.

--Speaker's forum or consultantships: None

--Patents or financial holdings in health-related companies: None

Dr. McCullough: Grant support: None

--Speaker's forum or consultantships: None

--Patents or financial holdings in health-related companies: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Clark AN, Mankikar GD, Gray I. Diogenes syndrome. A clinical study of gross neglect in old age. Lancet. 1975;1:366–368. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)91280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orem D. Nursing: Concepts of Practice. 5th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lauder W. The utility of self-care theory as a theoretical basis for self-neglect. J Adv Nurs. 2001;34:545–551. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halliday G, Banerjee S, Philpot M, et al. Community study of people who live in squalor. Lancet. 2000;355:882–886. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06250-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dyer CB, Goodwin JS, Vogel M, et al. Characterizing self-neglect: A report of over 500 cases seen by a geriatric medicine team. Unpublished manuscript. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pavlik VN, Hyman DJ, Festa NA, et al. Quantifying the problem of abuse and neglect in adults--analysis of a statewide database. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:45–48. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lachs MS, Williams CS, O'Brien S, et al. The mortality of elder mistreatment. JAMA. 1998;280:428–432. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.5.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fulmer T, Paveza G, Abraham I, et al. Elder neglect assessment in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs. 2000;26:436–443. doi: 10.1067/men.2000.110621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pavlou MP, Lachs MS. Could self-neglect in older adults be a geriatric syndrome? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:831–842. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agich GJ. Autonomy and Long-Term Care. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 5th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faden RR, Beauchamp TL. A History and Theory of Informed Consent. New York: Oxford University Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 13.State of Texas Statutes. Texas Probate Code. Vol Chapter XIII. Guardianship. 73rd legislature ed 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marson DC, Ingram KK, Cody HA, et al. Assessing the competency of patients with Alzheimer's disease under different legal standards. A prototype instrument. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:949–954. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540340029010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drane JF. Competency to give an informed consent. A model for making clinical assessments. JAMA. 1984;252:925–927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. The MacArthur Treatment Competence Study. I: Mental illness and competence to consent to treatment. Law Hum Behav. 1995;19:105–126. doi: 10.1007/BF01499321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grisso T, Appelbaum PS, Hill-Fotouhi C. The MacCAT-T: A clinical tool to assess patients' capacities to make treatment decisions. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48:1415–1419. doi: 10.1176/ps.48.11.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gill TG. Geriatric assessment. In: Society AG, editor. Geriatric Review Syllabus. 5th ed. New York: Blackwell; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lo B. Assessing decision-making capacity. Law Med Health Care. 1990;18:193–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.1990.tb00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cooney LM, Kennedy GJ, Hawkins KA, et al. Who Can Stay at Home? Assessing the Capacity to Choose to Live in the Community. Arch Intern Med. 1994;164:357–360. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lai JM, Karlawish JH. Assessing the capacity to make everyday decisions. Am J Geriatr Psych. 2006;15:101–111. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000239246.10056.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willis GB. Cognitive Interviewing: A "How To" Guide; Presented at the National Meeting of the American Statistical Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]