Abstract

Objectives

To investigate whether a priori selection of patient records using unexpectedly long length of stay (UL-LOS) leads to detection of more records with adverse events (AEs) compared to non-UL-LOS.

Design

To investigate the opportunities of the UL-LOS, we looked for AEs in all records of patients with colorectal cancer. Within this group, we compared the number of AEs found in records of patients with a UL-LOS with the number found in records of patients who did not have a UL-LOS.

Setting

Our study was done at a general hospital in The Netherlands. The hospital is medium sized with approximately 30 000 admissions on an annual basis. The hospital has two major locations in different cities where both primary and secondary care is provided.

Participants

The patient records of 191 patients with colorectal cancer were reviewed.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Number of triggers and adverse events were the primary outcome measures.

Results

In the records of patients with colorectal cancer who had a UL-LOS, 51% of the records contained one or more AEs compared with 9% in the reference group of non-UL-LOS patients. By reviewing only the UL-LOS group with at least one trigger, we found in 84% (43 out of 51) of these records at least one adverse event.

Conclusions

A priori selection of patient records using the UL-LOS indicator appears to be a powerful selection method which could be an effective way for healthcare professionals to identify opportunities to improve patient safety in their day-to-day work.

Keywords: Public Health, Length of Stay, Colorectal cancer, Record reviewing, trigger tool

Article summary.

Article focus

Record reviewing in order to identify adverse events is time-consuming.

A priori selection of patient records on the basis of unexpectedly long length of stay (UL-LOS) can be an efficient way to increase the chance of finding adverse events.

Key message

Selection of patient records with the UL-LOS and use of the Global Trigger Tool appear to be a powerful way of finding a majority of adverse events while limiting the number of patient records to be reviewed and thereby saving the reviewing physicians’ valuable time.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is the first study to look at the effectiveness of UL-LOS.

A limitation of the study is that it was investigated in only one group of patients. Future research should investigate the effectiveness of UL-LOS in other diagnostic groups.

Introduction

Within health services research, increased attention is focusing on patient outcomes. This results from the need to improve care and the need to reduce costs. As studies increasingly evaluate patient care, the need exists to identify adverse outcomes within patient medical records. This is a major challenge because medical records are usually extensive and sometimes difficult to evaluate. In the USA, this subject is being addressed by computer algorithms such as the Potentially Preventable Complications and the Potentially Preventable Readmissions software. These algorithms use hospital discharge abstract data to identify adverse outcomes in large populations. The development of these algorithms has been a long and resource intensive process.1 The current research addresses this important subject by developing a tool for identifying adverse outcomes in the Netherlands. The research involved patients at a medium-sized hospital where the volume of inpatients makes the identification of specific patients with adverse outcomes a challenging undertaking.

Furthermore, diminishing the number of patient-related adverse events became one of the top priorities for Dutch hospitals. A common way to achieve this is to learn from incidents and take action to prevent recurrence. To identify the adverse events, retrospective patient record review has become the ‘gold standard’ (inter)nationally.2–6 By retrospectively reviewing patient records, healthcare professionals are able to identify adverse events that occurred during the care process. Several studies on retrospective patient record review in different countries have shown a wide range of incidences of adverse events, varying from 2.9% to 16.6% with a median overall incidence of adverse events of 9.2%.7–9 This implies that, with random selection from all hospital records, a healthcare professional has to review 6–34 records to find one adverse event. These results show that although record reviewing has been proved very advantageous in finding adverse events, there is an important disadvantage: record reviewing is very time-consuming. Although most Dutch hospitals want to analyse their patient records for adverse events in order to identify patient safety opportunities, many hospitals are not able to mobilise enough physicians who can spend many hours reviewing patient records.

Looking for more efficient ways to organise patient record reviewing, we investigated how to increase the chance of finding adverse events. Previous research has shown strong relationships between adverse events and outcomes of quality indicators at patient and hospital level.10–12 For instance, one study identified a relationship between complications and increased mortality and length of stay (LOS).13 A recent study on the USA Veterans Health Administration data replicated these relationships between adverse events and patient safety indicators of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.14 Several other studies have indicated that adverse events often lead to prolonged LOS, and prolonged LOS could signal safety issues.15–24 Silber et al25 for instance showed that LOS can be used to reflect how well hospitals and providers deal with complications and adverse events.

The above mentioned studies suggest that negative results on quality indicators could be attributed to adverse events. In the current study, we hypothesise that records of patients with an unexpectedly long length of stay (UL-LOS) will show more adverse events. This patient safety indicator is already 3 years in use by Dutch hospitals and derived from administrative medical data. If so, the indicator could be used for selecting patient records in order to find more adverse events and save the valuable time of those reviewing patient records.

To test the hypothesis that looking for adverse events can be performed efficiently by selecting patient records using UL-LOS, we conducted a pilot study with a retrospective review of patient records in Tergooiziekenhuizen, a general hospital in the Netherlands. This article describes the pilot study. The results of this study might help hospitals organise their record-reviewing process in the most efficient way possible by using the quality indicator that already is available to them through existing registries.

Methods

The quality indicator UL-LOS

In our study, we used the quality indicator UL-LOS 2009 to make the a priori selection. The UL-LOS is based on the data from the National Medical Registration (LMR). The LMR contains demographical patient information, admission-related hospital data such as diagnosis and surgical procedures.26 UL-LOS is generated by indirect standardisation on three patient characteristics: age, primary diagnosis and the main procedure that the patient underwent. Age of the patient is divided into five classes of 0, 1–14, 15–44, 45–64 and 65 and older. For the primary diagnoses we used the diagnosis that led to the admission which includes approximately 1000 diagnoses classified by the ICD9 in three digits. Finally, the main procedure is determined by the Dutch Classification System of Procedures and is considered to depend on the diagnosis of the patient. On average it includes five main procedural groups. Together, these three parameters resulted in 5×5×1000=25 000 cells. For each cell the mean length of stay has been taken as the expected length of stay. Then the ratio between the actual length of stay and the expected length of stay is taken to calculate the UL-LOS. We define the UL-LOS as a LOS that is more than 50% longer than expected. Patients who died in the hospital are excluded. In addition, UL-LOS is a quality indicator Dutch hospitals use for their quality-improvement programmes and the Dutch Health Care Inspectorate uses UL-LOS in its supervision of hospital care.

Setting

The study was done in 2010 and 2011 at Tergooiziekenhuizen, a general hospital with nearly 30 000 clinical admissions a year. We used data and patient records from 2009. The hospital board gave us permission to use the data.

Reference groups

To assess the impact of the indicator UL-LOS, we selected from 191 colorectal admissions, records with the UL-LOS and compared these records with the reference group consisting of comparable patients from the same specialty population, who were treated at Tergooiziekenhuizen without a UL-LOS.

Analysis with the IHI Global Trigger Tool

A nurse used the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Global Trigger Tool to search all selected patient records for triggers.27 The nurse that did the screening of triggers for this study was experienced with the use of the Global Trigger Tool. Triggers may contain clues for identifying possible adverse events. This instrument adapts the classification from the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP28) Index for Categorising Errors. Although originally developed for categorising medication errors, these definitions can be easily applied to any type of adverse event. The IHI Global Trigger Tool was developed to count adverse events, determine the harm to the patient, and whether the adverse event was the result of a commission. According to the IHI, only cases of commission should be counted. However, we also counted cases of omission, as these are also a valuable source of possible quality improvement.6 29

Accordingly, the tool excludes the categories A to D from the NCC MERP Index, because these categories describe incidents that do not cause harm. We used the categories E to I, which do describe harm that may have contributed to or resulted in:

temporary harm to the patient and required intervention (category E);

temporary harm to the patient and required initial or prolonged hospitalisation (category F);

permanent patient harm (category G);

intervention required to sustain life (category H);

contributed to or resulted in the patient's death (category I).

A surgeon and an internist-nephrologist investigated and looked for adverse events in the patient records in which the nurse had found triggers. The physicians and the nurse were trained extensively according to the IHI Trigger Tool implementation programme to make sure that they all worked according to the same IHI methodology. The patient records were randomly divided between the physicians. They analysed these records in the same room in order to discuss difficult cases and make use of each other's expertise. If necessary, they consulted other physicians in the hospital to make their judgments as accurate as possible. The harm caused by an adverse event was categorised according to the NCC MERP Index as indicated above. They also classified the adverse events into five categories: care, operation, medication, intensive care (IC) and other.

A priori record selection with UL-LOS

We selected all records of patients with an admission for colorectal cancer in 2009. Patients with colorectal cancer are generally considered to be a homogenous population in terms of LOS, and are relatively vulnerable to adverse events.30 We excluded duplicated records, records of palliative patients and patients who died in the hospital. Then we selected patient records with a UL-LOS based on the calculations in the LMR discharge data. A nurse screened all these selected records for the presence of triggers with the trigger tool. Patient records with triggers were forwarded to the physicians to be investigated for adverse events and the possible harm to patients. We categorised all records on the basis of the ratio between actual and expected LOS, into four groups.

Actual LOS equal or less than 50% longer than expected

Actual LOS 50%—99% longer than expected

Actual LOS 100%—199% longer than expected

Actual LOS 200% or more above the expected LOS

The last three categories together form the patient group with a UL-LOS. The first category is the patient group we call non-UL-LOS which is at the same time the reference group. In sum, we pursued an approach to the record reviewing process by first making the selection on the basis of discharge abstract data and then working directly with patient medical records. In so doing, we have developed an effective tool which identifies adverse outcomes directly in hospital medical records that are being selected with the discharge abstract data.

Results

UL-LOS-based record selection

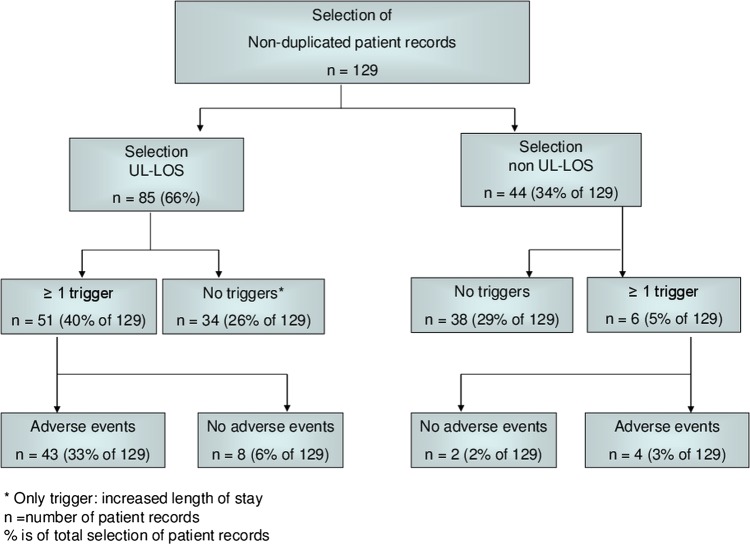

In 2009, the hospital in our study admitted, treated and discharged 191 patients with colorectal cancer. From this group, we excluded the duplicated patient records and patients who were admitted for palliative care which resulted in 129 unique patient records. From this group, we selected 85 patients with a UL-LOS (66%). Screening by our nurse with the trigger tool revealed that 51 of these UL-LOS records contained one or more triggers. Thus, 27% of 191 records remained to be reviewed by our physicians. Of these records, 43 patient records included one or more adverse events: 27 records contained one adverse event; 10 records contained two adverse events; 4 records contained three adverse events; and 2 records contained four adverse events (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart for number of patient records for each step in review process.

In table 1, we present the physicians’ classification. The adverse events were classified mainly as operation-related (45%), 60% of the adverse events were considered to have resulted in temporary harm to the patient and required initial or prolonged hospitalisation (category F).

Table 1.

Number, type and severity ratings of adverse events found in records of patients admitted with colorectal cancer and a unexpectedly long length of stay

| |

Type of adverse event |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Care | Medical | Operation | IC | Other | Total | ||

| Severity rating of adverse event | E: temporary harm to the patient and required intervention | 7 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 17 | 25% |

| F: temporary harm to the patient and required initial or prolonged hospitalisation | 9 | 4 | 21 | 2 | 4 | 40 | 60% | |

| G: permanent patient harm | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 7% | |

| H: intervention required to sustain life | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3% | |

| I: contributed to patient death | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4% | |

| Total | 18 | 6 | 30 | 3 | 10 | 67 | ||

| 27% | 9% | 45% | 4% | 15% | 100% | |||

The reference group: non-UL-LOS patients

Table 2 shows the number of adverse events compared between UL-LOS and non-UL-LOS patients. In the non-UL-LOS group, in 9% (4 of 44) of the reviewed records, at least one adverse event was found, compared with 51% (43 of 85) in the UL-LOS group. We also compared three categories within the UL-LOS (table 2).

Table 2.

Number of adverse events compared between UL-LOS and non-UL-LOS patients and within the UL-LOS categories

| N records | N records containing at least 1 trigger | N (and % of) records containing at least 1 adverse event | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-UL-LOS patients | 44 | 6 | 4 (9) |

| All patients with a UL-LOS | 85 | 51 | 43 (51) |

| Of which patients with 50%–99% longer-than-expected LOS | 33 | 14 | 9 (27) |

| Of which patients with 100%–199% longer-than-expected LOS | 32 | 22 | 20 (63) |

| Of which patients with 200% and above longer-than-expected LOS | 20 | 15 | 14 (70) |

UL-LOS, unexpectedly long length of stay; LOS, length of stay.

Discussion

The effectiveness of the methodology developed in the current research is impressive, demonstrating that a large majority of the records identified, contained one or more adverse events. With a priori selection using the UL-LOS indicator, we found adverse events in 51% of the records, compared with 9% in the non-UL-LOS group. By reviewing only the UL-LOS group with at least one trigger (66%), we found in 84% (43 of 51) of all the records with at least one adverse event in the colorectal patient group. Putting it another way, by reviewing only the UL-LOS group with at least one trigger, which is 40% of all patients, we found 91% of all records with at least one adverse event in the colorectal patient group. The fact that almost all records including one or more adverse events can be found by concentrating on records of patients with a UL-LOS and triggers is encouraging for hospitals struggling with a sparse capacity of reviewing physicians.

The percentages of records in which adverse events were identified in the different categories of UL-LOS show that the present formal quality indicator used by the Dutch Health Care Inspectorate identifies most adverse events. Our results show a rise in the percentage in which at least one adverse event was found from 50% longer LOS onwards. However, it also rises from 100% onwards. A more detailed study is needed to determine the appropriateness of the 50% threshold. These results apply to colorectal cancer. Future research could also investigate whether this threshold is appropriate for all diagnostic groups or whether we need varying percentages.

An interesting finding is that only 45% of the adverse events in a group of surgical patients such as those with colorectal cancer are related to the classification ‘operation’. It seems that quality of care is determined by the whole chain of care, not only by the quality of the organisation in the operating room or the professionals performing the operation.

Limitations

An important limitation of this study is that we identified the number of adverse events in a single specialty population and in only one hospital. Future research should investigate the validation on other populations and show whether identifying adverse events in more patient records, in more hospitals, gives comparable results.

Another limitation is the fact that, although we chose to have two physicians analyse the patient records together, both of them reviewed different records with consulting each other intensively. Therefore, we could not measure the inter-rater reliability. Our main concern was to organise the review process as efficiently as possible. Therefore, we chose parallel record reviewing. However, further research should show whether parallel analysis is reliable enough compared with consecutive analysis, which still contends with poor reliability.27 29 Although current study shows that the spare time of physicians can be saved by efficient record selection and Global Trigger Tool, experienced nurses can also review the patient records for the existence of adverse events. Then the physicians only have to determine the nurse's findings and assess the severity of harm. Such a strategy can save the time of physicians even more.

The results of this study are encouraging in showing that hospitals can and will use quality indicators based on administrative data for patient safety policy. This type of hospital data is usually easily available without an extra administrative burden for hospitals. Earlier research has shown the reliability of using administrative data in relation to clinical data.31 However, the reliability of indicators such as UL-LOS depends on the quality of coding in hospitals.32 Also in the Netherlands, the quality of administrative hospital data is subject to debate. If the quality of data coding in hospitals were to improve, the selection efficiency of quality indicators such as UL-LOS would probably be more accurate. The use of such quality indicators in combination with effective methods as Global Trigger Tool identify even more easily adverse events from the patient records.17 33

Conclusion

Easily available selection methods such as UL-LOS and the Global Trigger Tool may be a powerful way of finding a majority of adverse events while limiting the number of patient records to be reviewed and thereby saving the reviewing physicians’ valuable time. This could help hospitals to organise their patient safety policy as efficiently as possible.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank A Jonkheim, who screened all of the patient files and the physicians FC Henny and JW Juttmann of Tergooiziekenhuizen, who went through all the selected patient files.

Footnotes

Contributors: SC was the lead writer. SC, KH and HPM were PIs and were responsible for undertaking the data collection and analysis. IB, RBK and GPW provided input to the analysis. The initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by SC, IB and KH and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Lagoe RJ, Westert GP, Czyz AM, et al. Reducing potentially preventable complications at the multi hospital level. BMC Res Notes 2011;4:271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker GR, Norton PG, Flintoft V, et al. The Canadian Adverse Events Study: the incidence of adverse events among hospital patients in Canada. CMAJ 2004;170:1678–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davis P, Lay-Yee R, Briant R, et al. Adverse events in New Zealand public hospitals I: occurrence and impact. N Z Med J 2002;115:U271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michel P, Quenon JL, de Sarasqueta AM, et al. Comparison of three methods for estimating rates of adverse events and rates of preventable adverse events in acute care hospitals. BMJ 2004;328:199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson RM, Runciman WB, Gibberd RW, et al. The Quality in Australian Health Care Study. Med J Aust 1995;163:458–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zegers M, de Bruijne MC, Wagner C, et al. Adverse events and potentially preventable deaths in Dutch hospitals: results of a retrospective patient record review study. Qual Saf Health Care 2009;18:297–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas EJ, Studdert DM, Runciman WB, et al. A comparison of iatrogenic injury studies in Australia and the USA. I: context, methods, casemix, population, patient and hospital characteristics. Int J Qual Health Care 2000;12:371–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Runciman WB, Webb RK, Helps SC, et al. A comparison of iatrogenic injury studies in Australia and the USA. II: reviewer behaviour and quality of care. Int J Qual Health Care 2000;12:379–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Vries EN, Ramrattan MA, Smorenburg SM, et al. The incidence and nature of in-hospital adverse events: a systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care 2008;17:216–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhan C, Kelley E, Yang HP, et al. Assessing patient safety in the United States: challenges and opportunities. Med Care 2005;43:I42–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhan C, Miller MR. Administrative data based patient safety research: a critical review. Qual Saf Health Care 2003;12(Suppl 2):ii58–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iezzoni LI, Daley J, Heeren T, et al. Identifying complications of care using administrative data. Med Care 1994;32:700–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iezzoni LI. Risk adjustment for measuring health care outcomes. 3rd edn. Chicago: Health Administration Press, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rivard PE, Luther SL, Christiansen CL, et al. Using patient safety indicators to estimate the impact of potential adverse events on outcomes. Med Care Res Rev 2008;65:67–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoonhout LH, de Bruijne MC, Wagner C, et al. Nature, occurrence and consequences of medication-related adverse events during hospitalization: a retrospective chart review in the Netherlands. Drug Saf 2010;33:853–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoonhout LH, de Bruijne MC, Wagner C, et al. Direct medical costs of adverse events in Dutch hospitals. BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sari AB, Sheldon TA, Cracknell A, et al. Extent, nature and consequences of adverse events: results of a retrospective casenote review in a large NHS hospital. Qual Saf Health Care 2007;16:434–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ehsani JP, Jackson T, Duckett SJ. The incidence and cost of adverse events in Victorian hospitals 2003–04. Med J Aust 2006;184:551–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho SH, Ketefian S, Barkauskas VH, et al. The effects of nurse staffing on adverse events, morbidity, mortality, and medical costs. Nurs Res 2003;52:71–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Camp M, Chang DC, Zhang Y, et al. Risk factors and outcomes for foreign body left during a procedure: analysis of 413 incidents after 1 946 831 operations in children. Arch Surg 2010;145:1085–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lotfipour S, Kaku SK, Vaca FE, et al. Factors associated with complications in older adults with isolated blunt chest trauma. West J Emerg Med 2009;10:79–84 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams DJ, Olsen S, Crichton W, et al. Detection of adverse events in a Scottish hospital using a consensus-based methodology. Scott Med J 2008;53:26–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaushal R, Bates DW, Franz C, et al. Costs of adverse events in intensive care units. Crit Care Med 2007;35:2479–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rice-Townsend S, Hall M, Jenkins KJ, et al. Analysis of adverse events in pediatric surgery using criteria validated from the adult population: justifying the need for pediatric-focused outcome measures. J Pediatr Surg 2010;45:1126–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, Koziol LF, et al. Conditional length of stay. Health Serv Res 1999;34:349–63 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landelijke Medische Registratie (LMR) http://www.dutchhospitaldata.nl/registraties/lmrlazr/Paginas/default.aspx. (accessed 6 Oct 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Griffin F, Resar R. IHI global trigger tool for measuring adverse events. 2nd edn. Massachusetts: Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Index for Categorizing Errors. http://www.nccmerp.org/medErrorCatIndex.html. (accessed 6 Dec 2013)

- 29.Langelaan M, Baines RJ, Broekens MA, et al. Monitor Zorggerelateerde Schade 2008, dossieronderzoek in Nederlandse ziekenhuizen. Nivel, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sjo OH, Larsen S, Lunde OC, et al. Short term outcome after emergency and elective surgery for colon cancer. Colorectal Dis 2009;11:733–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aylin P, Bottle A, Majeed A. Use of administrative data or clinical databases as predictors of risk of death in hospital: comparison of models. BMJ 2007;334:1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van den Bosch WF, Kelder JC, Wagner C. Predicting hospital mortality among frequently readmitted patients: HSMR biased by readmission. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Classen DC, Resar R, Griffin F, et al. ‘Global trigger tool’ shows that adverse events in hospitals may be ten times greater than previously measured. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:581–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.