Abstract

Calorie restriction has been regarded as the only experimental regimen that can effectively lengthen lifespan in various animal models, but the actual mechanism remains controversial. The gut microbiota has been shown to have a pivotal role in host health, and its structure is mostly shaped by diet. Here we show that life-long calorie restriction on both high-fat or low-fat diet, but not voluntary exercise, significantly changes the overall structure of the gut microbiota of C57BL/6 J mice. Calorie restriction enriches phylotypes positively correlated with lifespan, for example, the genus Lactobacillus on low-fat diet, and reduces phylotypes negatively correlated with lifespan. These calorie restriction-induced changes in the gut microbiota are concomitant with significantly reduced serum levels of lipopolysaccharide-binding protein, suggesting that animals under calorie restriction can establish a structurally balanced architecture of gut microbiota that may exert a health benefit to the host via reduction of antigen load from the gut.

Calorie restriction has been shown to extend lifespan in diverse model systems, however, the mechanisms underlying this effect remain unclear. Zhang et al. show that calorie restriction changes the structure of the gut microbiota in mice, enriching for phylotypes positively correlated with lifespan.

Calorie restriction has been shown to extend lifespan in diverse model systems, however, the mechanisms underlying this effect remain unclear. Zhang et al. show that calorie restriction changes the structure of the gut microbiota in mice, enriching for phylotypes positively correlated with lifespan.

Since the initial study demonstrating the health-promoting and lifespan-extending effects of calorie restriction (CR) in mice1, benefits related to alleviating the metabolic syndrome have been observed in many mammals, including non-human primates and humans2,3. Despite various efforts, the actual mechanism remains controversial4,5.

Two recent, life-long metabonomic studies in dogs and monkeys revealed that CR was associated with changes in urinary bacterial metabolites, suggesting a potential connection among the gut microbiota, CR and aging6,7. Humans are considered supraorganisms with a vastly diverse and highly populated microbiota in the gut8,9, which can function as a metabolic organ to significantly modulate nutrition, metabolism and the immunity of its host10. After the host digests and absorbs nutrients from the diet, the remaining part will reach the colon to maintain a highly diverse and populated chemostatic culture11,12. The composition and amount of the diet work as a dominant force in shaping the gut microbiota12,13.

Changes in the gut microbiota responding to different diets, such as a high-fat diet versus normal chow, may have a pivotal role in the development of obesity and related diseases13,14,15,16,17,18. Gut microbiota disrupted by a high-fat diet may produce higher amounts of endotoxin and increase gut permeability, leading to a higher plasma level of endotoxin, a higher level of inflammation and eventually the development of metabolic disorders13,14,19,20. Our recent study showed that one endotoxin-producing strain isolated from the gut of an obese human caused obesity and insulin resistance in germ-free mice. These bacterium-induced obese mice had a significantly elevated serum endotoxin load and increased systemic and local inflammation, indicating a causative role of the endotoxin-producing members in the gut microbiota in metabolic syndrome21. However, it remains to be elucidated how far and to what direction the gut microbiota can be shifted by changing only the amount of food intake such as in CR treatment.

Recently, Zhou et al.22 identified genetic modulators of aging by analysing mid-life gene expression in the liver of a mouse model with life-long dietary and exercise interventions. In that study, male C57BL/6 J mice were subjected to either a low-fat diet (10% fat, D12450B, Research Diets) or a high-fat diet (60% fat, D12492, Research Diets). For each type of diet, animals were divided into three groups: (1) fed ad libitum with sedentary activity in the cage (LFD or HFD), (2) fed 70% of the ad libitum (LFD+CR or HFD+CR) or (3) fed ad libitum with voluntary wheel-running exercise (LFD+Ex or HFD+Ex). Each group had 30 individually caged animals, and the entire trial lasted almost 4 years until all animals died22. The longest living and healthiest animals were in the LFD+CR group. Relative to the LFD group, their median lifespan (153 weeks) and maximum lifespan (185.5±1.6 weeks) increased by approximately 20% and 25%, respectively. The LFD+CR group also exhibited the lowest and most stable body weight and fat content, as well as the best metabolic phenotypes, such as glucose homoeostasis and serum lipid profile, at the different indicated ages throughout their lifespan. The HFD group had the shortest lifespan and the worst metabolic phenotypes. Compared with the HFD control group, restricted high-fat diet intake (HFD+CR) resulted in dramatic extensions of the median and maximum lifespans (both by ~36% from 101 to 137 weeks and from 118.8±1.5 to 161.9±1.5 weeks, respectively), which became similar to those of the LFD (127 and 148.7±3.1 weeks, respectively) and LFD+Ex (131 and 159.6±3.7 weeks, respectively) groups. In addition, similar metabolic phenotypes were observed among these groups. Voluntary running exercise resulted in a significant increase in the median and maximum lifespan (by ~13%, from 101 to 114 weeks, and by ~18%, from 118.8±1.5 to 139.7±1.9 weeks, respectively) when animals were fed ad libitum on high-fat diet but not on low-fat diet. Together, these data demonstrate that obesity-related metabolic syndrome is highly associated with accelerated aging and reduced lifespan. CR can more effectively alleviate diet-associated metabolic disorders and attenuate aging than voluntary exercise, leading to a prolonged healthy lifespan, consistent with early studies in rats22.

In the current study, we use faecal and serum samples from the same animal trial as Zhou et al.22 to investigate the impact of life-long CR and voluntary exercise on the endotoxin load and architecture of gut microbiota and pinpoint the association between a specific combination of populations in the gut microbiota and the variations in healthy phenotype and lifespan of their hosts. Our findings suggest that an improved architecture of gut microbiota may be a critical element in mediating the health-promoting actions of CR, highlighting the potential of modulation for gut microbiota in developing effective anti-aging dietary interventions.

Results

Overall structural changes of gut microbiota in life-long CR

To determine whether the CR-mediated protection of mice against obesity-associated metabolic syndrome and promotion of healthy aging are associated with alteration of gut microbiota structure, we first profiled the overall structural changes of gut microbiota from all available animals at 62, 83 and 141 weeks of age by bar-coded pyrosequencing of the V3 region of 16S rRNA genes. Of 293,557 valid reads from 288 samples with an average of 1,019 reads per sample (±205 s.d.), 4,613 species-level operational taxonomic units (OTUs) were delineated using 97% as a homology cut-off value (Supplementary Fig. S1).

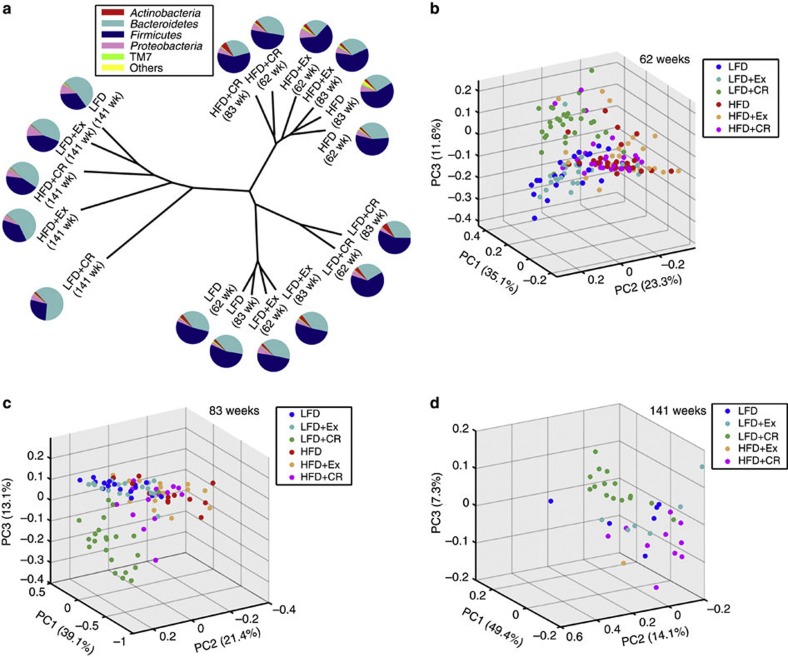

β-Diversity analysis can indicate the extent of similarity between microbial communities by measuring the degree to which membership or structure is shared between communities23. Based on the data matrix of the weighted UniFrac distance, unweighted pair-group method using arithmetic averages and principal coordinate analysis showed both age-dependent and diet-responsive structural rearrangement of gut microbiota (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. S2). Although no significant age-related shift of gut microbiota was observed around mid-life ages (between 62 and 83 weeks), the gut microbiota from all groups of mice alive at the late-life age of 141 weeks displayed the same trend of moving into an ‘aging space.’ Conversely, separated microbiota clusters were observed in high-fat diet-fed mice relative to low-fat diet-fed mice at the two mid-life ages. Moreover, in parallel with its profound effects on health improvement and longevity, CR showed more prominent impact on the overall architecture of gut microbiota than exercise, particularly with unique microbiota clusters detected in the LFD+CR group both at mid-life and late-life ages. The differences between the gut microbiota of animals with or without voluntary exercise were not significant in the present study. These results suggest a possible correlation of the clustering pattern of gut microbiota with the health conditions in response to life-long nutritional intervention.

Figure 1. Age-dependent and diet-responsive alteration trajectories of global gut microbiota structures.

(a) Unweighted pair-group method using arithmetic average based on the weighted UniFrac distance of gut microbiota from the six groups of mice at 62, 83 and 141 weeks (wk) of age. The average relative abundance (% of total 16S rRNA gene V3 region sequences) of bacterial lineages of the gut microbiota within each group of mice is displayed as pie charts at the phylum level. Weighted UniFrac principal coordinate analysis of animals at (b) 62 (LFD, n=21; LFD+CR, n=29; LFD+Ex, n=22; HFD, n=28; HFD+CR, n=29; and HFD+Ex, n=23), (c) 83 (LFD, n=16; LFD+CR, n=22; LFD+Ex, n=19; HFD, n=12; HFD+CR, n=14; and HFD+Ex, n=15) and (d) 141 (LFD, n=6; LFD+CR, n=15; LFD+Ex, n=6; HFD, n=0; HFD+CR, n=10; and HFD+Ex, n=1) weeks of age.

Specific phylotypes modulated by life-long CR

As an algorithm to robustly identify features that are statistically different among biological classes, linear discriminant analysis (LDA) effect size (LEfSe)24 was employed to identify specific phylotypes responding to life-long CR at both mid-life (62 weeks of age) and late life (141 weeks of age). We did not analyse data at 83 weeks of age because there is no significant age-related shift of gut microbiota between 62 and 83 weeks.

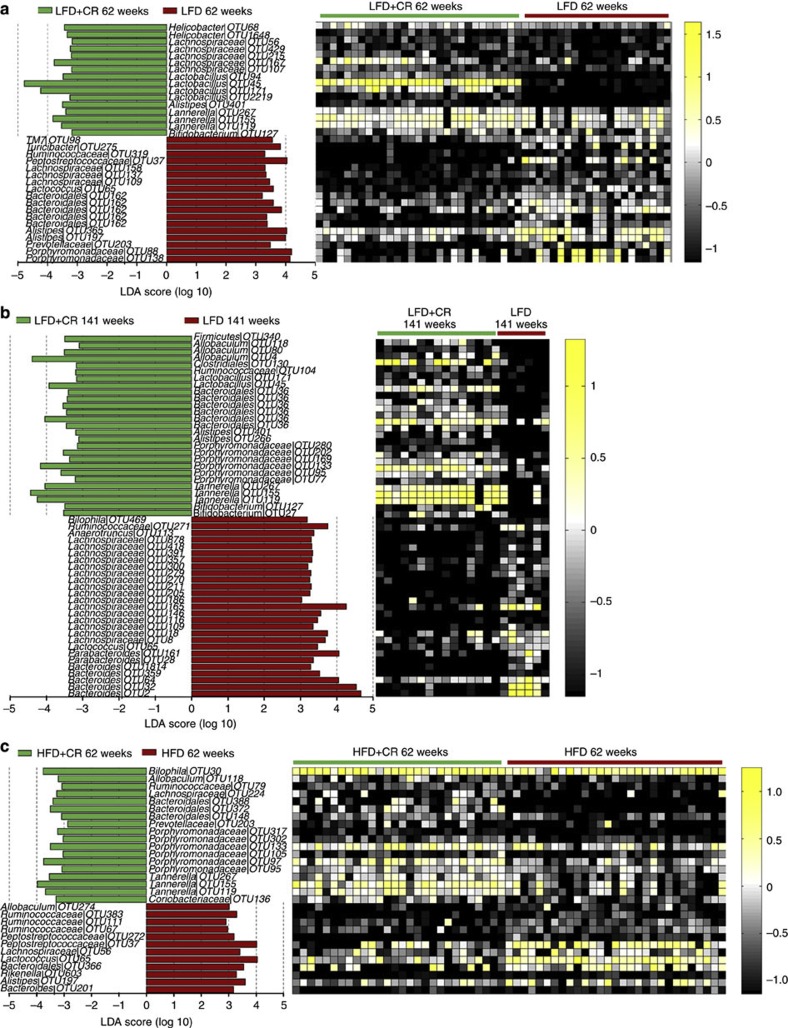

In mid-life, 34 phylotypes at the OTU level were discovered as high-dimensional biomarkers for separating gut microbiota between LFD and LFD+CR mice (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table S1). Sixteen of these OTUs were higher, and eighteen were lower in the CR than in the ad libitum group. For example, the abundances of these selected phylotypes in Streptococcaceae (OTU65 belonging to Lactococcus) and TM7 (OTU98) were lower in CR animals. Interestingly, OTU45 in the genus Lactobacillus was one of the most predominant phylotypes in bacterial communities of LFD+CR mice but was notably low in LFD mice (12.4% versus 0.05%, respectively; P<0.001, one-way ANOVA).

Figure 2. Key phylotypes of gut microbiota responding to life-long CR identified using LEfSe.

(a) LFD (n=21) versus LFD+CR (n=29) mice at 62 weeks. (b) LFD (n=6) versus LFD+CR (n=15) mice at 141 weeks. (c) HFD (n=28) versus HFD+CR (n=29) mice at 62 weeks. The left histogram shows the LDA scores computed for features (on the OTU level) differentially abundant between the ab libitum and CR mice. The right heat map shows the relative abundance (log 10 transformation) of OTUs.

At the late-life age of 141 weeks, 27 OTUs were higher and 27 were lower in the LFD+CR group than in the LFD group (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table S2). Ten of these OTUs were also significantly different between the two treatment groups in mid-life. For example, although OTU45 in the genus Lactobacillus was not the predominant phylotype in bacterial communities of LFD+CR mice, the relative abundance of this OTU was still higher in LFD+CR mice than in LFD mice (1.7% versus 0.024%, respectively; P<0.001, one-way ANOVA). Different from mid-life, the OTUs belonging to Bifidobacterium were higher in LFD+CR mice, but the OTU469 of Desulfovibrionaceae was lower in LFD+CR mice. Some members in the genus Bifidobacterium are well-known probiotic strains25, and some in the family Desulfovibrionaceae have previously been found to be positively associated with obesity and inflammation13.

The mice had a significantly different gut microbiota structure between the LFD and HFD groups (Supplementary Fig. S3), confirming results of previous studies13,18. CR also shifted the gut microbiota in mice fed with high-fat diet but not as dramatic compared with their low-fat diet companions (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. S4). In mid-life, 30 phylotypes were selected as key variables for separating the gut microbiota under different food intake conditions (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Table S3); 18 of them were higher and 12 were lower in the HFD+CR group than in the HFD group. All the phylotypes in Porphyromonadaceae were higher in the HFD+CR than in the HFD group. Most of the OTUs responding to CR in HFD+CR mice were not found in LFD+CR mice. Only three OTUs (in Lactococcus (OTU65), Bacteroidales (OTU366) and Peptostreptococcaceae (OTU37), respectively) were reduced, and three OTUs in Tannerella (OTU119, 155 and 267) were increased by CR both with mice fed with high-fat diet and low-fat diet. Because all the HFD mice had died before 141 weeks, we could not obtain any data regarding gut microbiota responding to restriction of high-fat diet intake at the late-life stage of mice.

We also employed partial least square discriminate analysis to confirm the results, and the identified specific phylotypes responding to life-long CR were similar to those from LEfSe (Supplementary Figs S5 and S6).

We also identified a few OTUs that were different between the mice in the exercise group and their ad libitum companions by LEfSe; however, the relative abundance of these OTUs was very low (Supplementary Fig. S7). Conversely, efforts to classify groups with or without voluntary exercise on the same diet with partial least square discriminate analysis did not establish validated models, indicating that the differences between the gut microbiota of animals with or without voluntary exercise were not significant in the present study.

Structural modulation of gut microbiota during aging

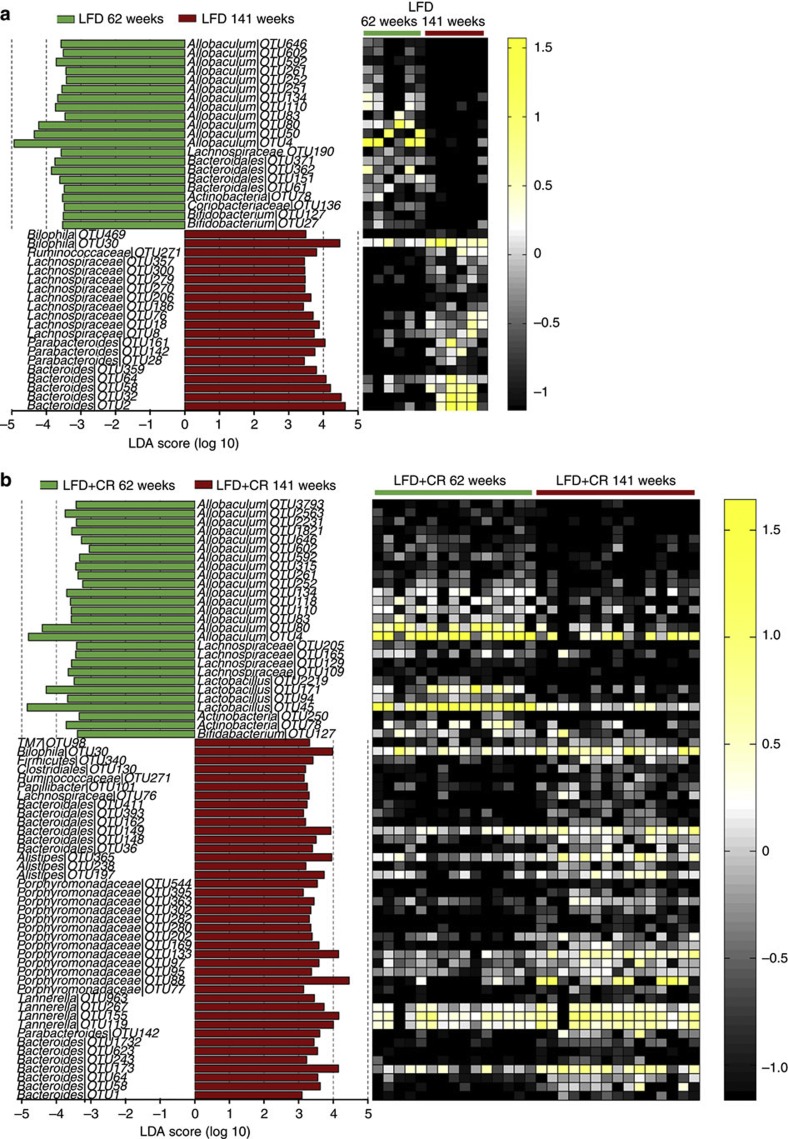

Further analysis suggested that CR significantly affected the succession of gut microbiota during aging. Division-level analysis showed that the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio of gut microbiota in all the mouse groups decreased from 62 to 141 weeks (Fig. 1a). Using LEfSe, we compared the gut microbiota of mice in each group between mid-life and late life to identify the specific phylotypes with OTU levels associated with aging.

In LFD mice, the phylotypes mainly responsible for decrease of the phylum Firmicutes during aging were in the genus Allobaculum (12 OTUs; 28.1% at 62 weeks versus 0.20% at 141 weeks) (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table S4). In LFD+CR mice, not only OTUs in the genus Allobaculum (29.7% at 62 weeks versus 7.2% at 141 weeks) but also OTUs in the genus Lactobacillus (21.0% at 62 weeks versus 2.0% at 141 weeks) made a significant contribution to the decrease of Firmicutes during aging (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table S5).

Figure 3. Key phylotypes of gut microbiota responding to aging.

(a) LFD+CR mice (n=15). (b) LFD mice (n=6). The left histogram shows the LDA scores computed for features (OTU level) differentially abundant between 62 and 141 weeks. The right heat map shows the relative abundance (log 10 transformed) of OTUs.

Conversely, the increase of the phylum Bacteroidetes during aging in LFD mice was due to the increase of OTUs in the genus Bacteroides (family Bacteroidaceae; 0.84% at 62 weeks versus 26.7% at 141 weeks). However, in LFD+CR mice, OTUs in the family Porphyromonadeceae (9.4% at 62 weeks versus 28.2% at 141 weeks), instead of bacteria in Bacteroides, were largely responsible for the increase of Bacteroidetes with age. Thus, the apparent phylum level changes associated with aging were actually mediated by different phylogenetic groups in animals with or without CR treatment.

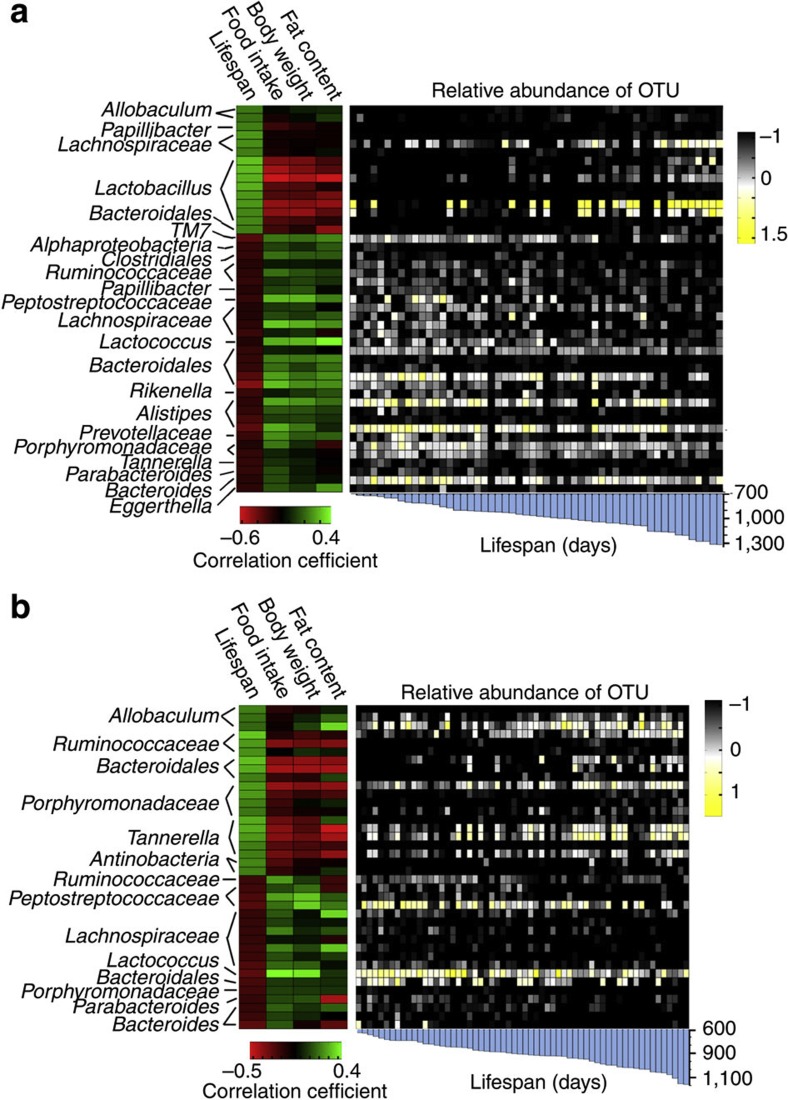

Correlation of mid-life gut microbiota with lifespan

We next used the Kendall tau rank correlation coefficient to directly measure the correlation between the phylotypes of gut microbiota in mid-life and the lifespan based on two types of diet. We identified that 45 OTUs significantly correlated with lifespan in mice fed on low-fat diet. Except for one Bacteroidales OTU, the remaining 15 OTUs significantly positively correlated with lifespan belonged to Firmicutes. Particularly, eight OTUs in Lactobacillus showed strong correlation with lifespan. The 30 phylotypes negatively correlated with lifespan were distributed in the five Phyla of Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria and TM7 (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table S6). In the mice on the high-fat diet, 20 OTUs were positively correlated, and 18 OTUs were negatively correlated with lifespan, most of which were in Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, except for two Actinobacteria OTUs (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table S7). Because of the strong impact of different diet backgrounds on the gut microbiota, only three OTUs in Lactococcus (OTU65), Bacteroidales (OTU366) and Peptostreptococcaceae (OTU37) showed the same behaviour both in mice on low-fat diet and high-fat diet. These three OTUs were negatively correlated with lifespan. We also found that the OTUs belonging to the same family or genus could have opposite correlation with lifespan. For example, in the mice fed with low-fat diet, there were three OTUs in Lachnospiraceae positively correlated with lifespan, but the other four OTUs in the same family were negatively correlated with lifespan.

Figure 4. Correlation of mid-life gut microbiota with lifespan.

The phylotypes significantly correlated with lifespan in mid-life (62 weeks) gut microbiota of animals on (a) low-fat diet (LFD, n=15; LFD+CR, n=22; and LFD+Ex, n=17) and (b) high-fat diet (HFD, n=21; HFD+CR, n=21; and HFD+Ex, n=18). The left heat map shows the correlation coefficient between these OTUs and physiological parameters of mid-life. The right heat map shows the relative abundance (log 10 transformed) of OTUs. The bottom bar shows the lifespan of each mouse.

Mid-life metabolic phenotypes, such as food intake, body weight and fat content, were highly correlated with lifespan, a finding that has been reported by Zhou et al22. Most of the OTUs significantly positively correlated with lifespan showed strong negative correlation with food intake, body weight and fat content, and vice versa (Fig. 4a).

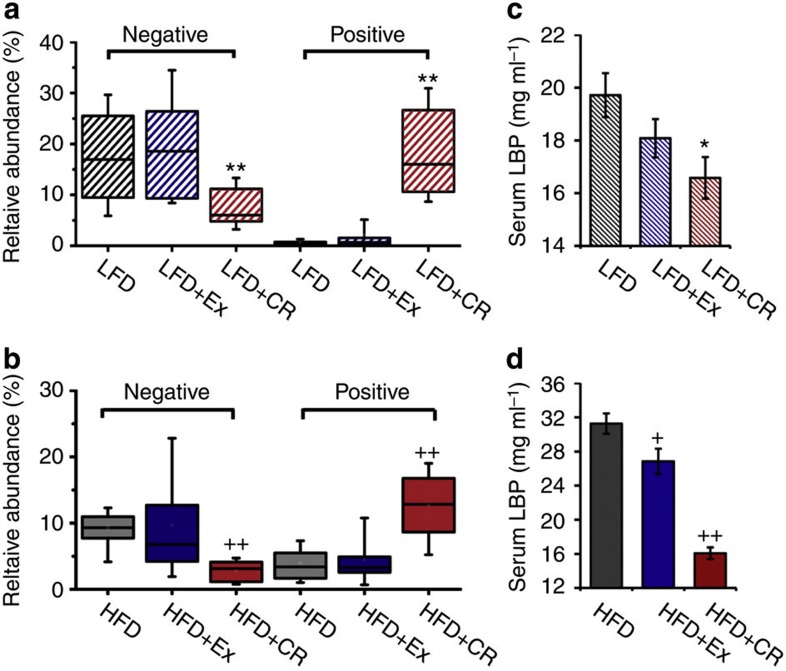

CR reduces antigen load to the hosts from the gut microbiota

Through long-term CR, the relative abundance of the OTUs negatively correlated with lifespan was significantly reduced, and the relative abundance of OTUs positively correlated with lifespan was increased in mice both on low-fat diet and high-fat diet (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Figs S8 and S9). The serum levels of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding protein (LBP) from all available animals at mid-life were measured to determine the antigen load from the gut microbiota. Compared with their ab libitum companions, LBP levels were lower in mice from the two CR intervention groups (Fig. 5c). Conversely, exercise showed no significant impact on both the relative abundance of OTUs correlated with lifespan and the serum level of LBP. These results suggest that modulation of the gut microbiota by CR could significantly reduce the antigen load to the host, contributing to CR-induced lifespan extension.

Figure 5. Gut microbiota-associated antigen load changes.

Relative abundance of the phylotypes negatively and positively correlated with lifespan of mice on (a) low-fat diet (LFD, n=15; LFD+CR, n=22; and LFD+Ex, n=17) and (b) high-fat diet (n=21; HFD+CR, n=21; and HFD+Ex, n=18) at 62 weeks. The boundary of the box closest to zero indicates the 25th percentile, a line within the box marks the median, and the boundary of the box farthest from zero indicates the 75th percentile. Whiskers (error bars) above and below the box indicate the 90th and 10th percentiles. The serum level of LBP of mice on (c) low-fat diet (LFD, n=7; LFD+CR, n=8; and LFD+Ex, n=7) and (d) high-fat diet (HFD, n=8; HFD+CR, n=8; HFD+Ex, n=7) at 62 weeks (shown as mean±s.e.m.). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 versus LFD, +P<0.05 and ++P<0.01 versus HFD by analyses of variance.

Discussion

Among the efforts to understand the mechanisms by which reduced dietary intake improves health and lifespan, the current study is unique in that it focused on the changes of gut microbiota induced by life-long CR to determine whether these changes are associated with improved healthy phenotypes and lifespan.

Different dietary composition can mould the divergent structure of gut microbiota13,26,27,28,29. For example, human populations with a modern western diet or a rural diet showed distinct gut microbiota structures29. The changes in overall structure of gut microbiota induced by high-fat diet versus normal chow may act as an important mediator in the aetiology of obesity and related metabolic diseases via disrupting host lipometabolism regulation15,18,30,31,32 and inducing low-grade inflammation13,14,19,20.

In the current study, we also observed shifting of gut microbiota induced by high-fat diet versus low-fat diet (data shown in Supplementary Materials). However, the most interesting result was that, compared with the ad libitum group, mice with 30% restriction of low-fat diet had a unique gut microbiota, demonstrating that the gut microbiota can be substantially modulated by only restricting the intake of diet. This is different from previous reports that dietary restriction had little effect on the gut microbiota33,34,35. This discrepancy may be due to the short duration of CR, different model systems used (rat and human) and limitation of technology for analysis of gut microbiota used in previous studies. The 454 pyrosequencing method used in the present study, although with its own bias due to the primer design (V3 region targeted) and chosen DNA extraction method, can still allow much deeper and more comprehensive analysis of changes in the gut microbiota responding to CR than that in previous reports.

Previous studies have suggested that because of the global impact on the physiology of the intestinal tract, including the decrease of intestinal motility, decline in the functionality of the immune system (immunosenescence), and changes in nutritional behaviour and life style of aged people, aging can seriously affect the composition of gut microbiota36,37,38,39. In the current study, the gut microbiota in all mice changed during aging; however, the most interesting finding was that the shifts of gut microbiota with aging were different among different dietary intervention groups. This finding also suggests that life-long nutritional conditions have an impact on not only the structure and composition of gut microbiota but also the interaction between the host and gut microbiota.

Our approach of directly measuring lifespan as well as measuring dietary and other metabolic conditions, although extremely tedious and costly (more than 150 mice over a time span of 3 years), allowed us to identify the phylotypes of gut microbiota that may be directly associated with lifespan. Correlation analysis between the gut microbiota at mid-life and lifespan identified phylotypes that are positively correlated with lifespan and those that are negatively correlated with lifespan under each of the two dietary backgrounds. On both the high-fat diet and low-fat diet, CR increased those phylotypes that were positively correlated with lifespan, and decreased those that were negatively correlated with lifespan. Phylotypes positively correlated with lifespan may contain beneficial bacteria, whereas those negatively correlated with lifespan may have harmful bacteria such as opportunistic pathogens. For example, the longest-lived and healthiest LFD+CR group had a gut microbiota with astonishingly high populations in Lactobacillus spp. Members in the genus Lactobacillus spp. have been known to inhibit pathogen adhesion to the intestinal wall, protect against pathogen-induced gut barrier disruption and reduce inflammatory cytokines40,41. In addition, the LFD+CR group had the lowest level of phylotypes in Streptococcaceae and TM7. It has been shown in humans that some strains in Streptococcaceae can induce mild inflammation, contributing to the disproportionate morbidity associated with chronic wounds among diabetics compared with non-diabetics42,43. Members in TM7 may have an important role in the early stages of inflammatory mucosal processes in inflammatory bowel diseases44.

The increase of beneficial bacteria such as Lactobacillus and decrease of opportunistic pathogens may reduce antigen load to the host and help alleviate inflammation and metabolic syndrome13,14,19,20. Our data showed that CR mice had reduced LBP levels in the serum. LBP is a soluble acute phase protein that binds to LPS, the most abundant gut antigen from the gut with the most potent inflammation-provoking capacity, in eliciting immune responses by presenting LPS to surface pattern-recognition receptors, such as CD14 and TLR4, of immune cells45. LBP can also bind to antigens produced by Gram-positive bacteria and, thus, may represent one biomarker that links antigen load in the blood and the host inflammatory response46. The significant decrease of the ratio of the bacteria negatively and positively correlated with lifespan in animals under CR may minimize antigen entrance into the blood from the gut, a result that may constitute a crucial component in CR-mediated benefits to the host13,14. Similar to the result of gut microbiota, the measurement of mid-life liver gene expression of mice from the same trial by whole-genome microarrays showed that LFD+CR mice demonstrated a distinctive expression pattern from other groups, which correlated with longevity and health status22. Most notably, the gene expression levels of the toll-like receptor signalling pathway and inflammation-related pathways were negatively correlated with lifespan and positively correlated with body weight and metabolic deterioration. Because the toll-like receptor signalling pathway mainly responds to antigens such as endotoxins from the gut microbiota47, its downregulation supports the hypothesis that CR might display reduced antigen load from the gut microbiota to the hosts, possibly by modulating the structure of the gut microbiota to a more balanced state.

The gender of the host is known to have an impact on lifespan, healthy phenotypes and the immune responses48,49,50. In addition, gender may also be involved in the determination of the mammalian gut microbiota. The gender-related bacteria identified from different studies included species of Bacteroides–Prevotella, Clostridia, Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria and so on28,49,51. To avoid the influence of gender as a confounding factor, we only used male mice. The response of gut microbiota to CR in female mice may be different from the results we observed in the current study, and it remains an interesting issue to be investigated.

The molecular cascades between dietary modulation, the gut microbiota and host health remain to be elucidated. The diet can be used by both the host and gut microbiota11,12. The competition between the host and gut bacteria for nutrients may determine the composition of the feeding medium for homoeostatic control of microbiota in the lower gut. It is conceivable that under conditions of restricted nutrient availability, as in the case of mice in the LFD+CR group, the host may extract nutrients (such as proteins and fats) more thoroughly, leaving primarily indigestible plant polysaccharides to the colon. In other words, CR without malnutrition might actually increase the relative content of fibre in the animal’s diet. This ‘oligotrophic condition’ with mainly fibre available for gut microbes might promote the growth of beneficial bacteria, such as gut barrier protectors and butyrate producers52, but suppress opportunistic pathogens53. This hypothesis warrants further studies.

Our results point to the health-promoting potential of a balanced gut microbiota architecture induced by CR, revealing a possible close connection between nutritional modulation of gut microbiota and healthy aging. More mechanistic studies are needed to validate and expand the interesting findings provided here via this microbiome-wide association study54. Given the potential key role in mediating the health-promoting actions of CR, an architecturally improved gut microbiota may become a novel surrogate biomarker for the development of effective anti-aging dietary interventions.

Methods

Animal intervention and samples

The animal experimental procedures, approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute for Nutritional Sciences, CAS, were described previously by Zhou et al22. Male C57BL/6 J mice at 5 weeks of age were randomly assigned to one of the six groups (n=30 for each group) and individually caged for a life-long trial: (1) low-fat diet with sedentary activity (LFD), (2) low-fat diet with 30% CR and sedentary activity (LFD+CR), (3) low-fat diet with voluntary running exercise (LFD+Ex), (4) high-fat diet with sedentary activity (HFD), (5) high-fat die with 30% CR and sedentary activity (HFD+CR) and (6) high-fat diet with voluntary running exercise (HFD+Ex). All faecal and serum samples for the current study were collected from this animal trial.

Fresh faecal matter was collected from the above animal trial at 62 weeks (LFD, n=21; LFD+CR, n=29; LFD+Ex, n=22; HFD, n=28; HFD+CR, n=29; and HFD+Ex, n=23), 83 weeks (LFD, n=16; LFD+CR, n=22; LFD+Ex, n=19; HFD, n=12; HFD+CR, n=14; and HFD+Ex, n=15) and 141 weeks (LFD, n=6; LFD+CR, n=15; LFD+Ex, n=6; HFD, n=0; HFD+CR, n=10; and HFD+Ex, n=1) of age. At 62 weeks, eight randomly selected mice from each group were humanely euthanized for serum samples collection for LBP analysis. All the faecal samples were stored at −80 °C until analysis.

Pyrosequencing of the V3 region of 16S rRNA genes

DNA was extracted using the PSP®Spin Stool DNA Plus Kit (Invitek GmbH, Germany). The primers P1 and P2 (5′-NNNNNNCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′ and 5′-NNNNNNATTACCGCGGCTGCT-3′) correspond to positions 341 to 534 in the Escherichia coli 16S rRNA gene, with a sample-unique DNA barcode of six-mer sequences at the 5′ end, were used to amplify the V3 region of each faecal sample by PCR. PCR reactions were run in a thermocycler PCR system (PCR Sprint; Thermo electron, Corp., UK) using the following programme: 3 min of denaturation at 94 °C followed by 20 cycles of 1 min at 94 °C (denaturation), 1 min for annealing (1 °C reduced for every two cycles from 65 to 57 °C, followed by one cycle at 56 °C and one cycle at 55 °C) and 1 min at 72 °C (elongation), with a final extension at 72 °C for 6 min. The products from different samples were mixed at equal ratios for pyrosequencing using the GS FLX platform (Roch, Branford, CT, USA).

Bioinformatics and statistical analysis of sequencing data

The standards for quality control of selecting valid reads for analysis were as follows: if a sequence (a) shows no mismatch to the barcode and 16S rRNA gene primer at sequencing end, (b) is more than 100 nucleotides in length, (c) has no more than two undermined bases in the sequence read and (d) finds >75% mach to a previously determined 16S rRNA gene sequence, as reported previously55,56,57. The sequences were aligned using NAST, and delineation of OTUs was conducted with DOTUR at 97% cutoff58. The length of the sequence fragments used for the analysis was from 92 to 183 nucleotides (without primer and barcode). The alpha and beta diversities were performed using QIIME59. The GAST (Global Alignment for Sequence Taxonomy) process was used to select the top GAST match (es) of the representative sequence of each OTU to assign taxonomic classification60. The V3 reference databases (V3 RefDB) and software for GAST analysis were downloaded from http://vamps.mbl.edu/resources/software.php. The V3 RefDB is composed of publicly available, high-quality, full-length 16S rRNA sequences from Silva release 92 ( http://www.arb-silva.de/) with taxonomic classifications obtained from the RDP Classifier (with a minimum 80% bootstrap score) and contains 381,203 V3 tags. The representative sequence of each OTU was assigned the taxonomic classification of the most similar reference sequence or sequences in the V3 RefDB as described previously60.

LEfSe24 is an algorithm for high-dimensional biomarker discovery and explanation that identifies genomic features (genes, pathways or taxa) characterizing the differences between two or more biological conditions (or classes; see figure below). LEfSe emphasizes both statistical significance and biological relevance, allowing researchers to identify differentially abundant features that are also consistent with biologically meaningful categories (subclasses). We performed LEfSe analysis on the website http://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/galaxy. The differential features were identified on the OTU level. The treatment groups or time points were used as the class of subjects (no subclass). LEfSe analysis was performed under the following conditions: (1) the alpha value for the factorial Kruskal–Wallis test among classes is <0.05 and (2) the threshold on the logarithmic LDA score for discriminative features is >2.0.

Based on two diets, associations between each OTU (filtered for an OTU subject prevalence of at least 10%) at 62 weeks and lifespan were determined using the Kendall tau rank correlation coefficient under Matlab (ver. 7.1; The MathWorks, Inc.). The OTU was considered significantly correlated with lifespan for P<0.05. Thereafter, the Kendall tau rank correlation coefficient between these selected OTU and physiological parameters (food intake, body weight and fat content) of mid-life was also calculated.

Serum LBP measurements

Blood samples were collected from the tail vein after overnight fasting and centrifuged at 12,000 r.p.m. for 30 min to pellet blood cells, and the serum was stored at −80 °C until further analyses. Serum LBP was determined after a dilution of 1:800 using the Mouse Lipopolysaccharide Binding Protein ELISA Kit (Cell Sciences, Canton, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Author contributions

L.Z., Y.L. and Y.Z. designed and supervised the research project and wrote the paper. S.L., L.Y., P.H. and W.L. performed the animal studies and analysed the physiological data. C.Z. collected faecal samples, designed pyrosequencing barcodes, conducted pyrosequencing and bioinformatics analysis and wrote the paper. S.W. and G.Z. did the pyrosequencing. M.Z. and X.P. helped analyse the data.

Additional information

Access code: Sequence information: all sequence data have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under accession code SRA012394.1.

How to cite this article: Zhang, C. et al. Structural modulation of gut microbiota in life-long calorie-restricted mice. Nat. Commun. 4:2163 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3163 (2013).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures S1-S9, Supplementary Tables S1-S7, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References

Acknowledgments

We thank C.B. Newgard (Duke University) for the initial design of the animal intervention study. This work was supported by the following grants: China MOST (2012CB524900, 2011CB910900, 2007DFC30450, 2009ZX10004-601, 2006BAI11B08, 2088AA02Z315, and 2007CB513002); NSFC (No. 30730005, 3112106, No. 30988002, 31230036, 81021002 and 91213306); CAS (No. KSCX2-EW-R-09), Shanghai STC (No. 10XD1406400), and US ADA Research Award 7-06-RA-165.

References

- McCay C. M., Crowell M. F. & Maynard L. A. The effect of retarded growth upon the length of life span and upon the ultimate body size. J. Nutr. 10, 63–79 (1935). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colman R. J. et al. Caloric restriction delays disease onset and mortality in rhesus monkeys. Science 325, 201–204 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana L., Meyer T. E., Klein S. & Holloszy J. O. Long-term calorie restriction is highly effective in reducing the risk for atherosclerosis in humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 6659–6663 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf G. Calorie restriction increases life span: a molecular mechanism. Nutr. Rev. 64, 89–92 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarente L. Mitochondria—a nexus for aging, calorie restriction, and sirtuins? Cell 132, 171–176 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. Metabonomic investigations of aging and caloric restriction in a life-long dog study. J. Proteome Res. 6, 1846–1854 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezzi S. et al. Metabolic shifts due to long-term caloric restriction revealed in nonhuman primates. Exp. Gerontol. 44, 356–362 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lederberg J. Infectious history. Science 288, 287–293 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin J. et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 464, 59–65 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman A. L. & Gordon J. I. Our unindicted coconspirators: human metabolism from a microbial perspective. Cell Metab. 12, 111–116 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenburg J. L., Angenent L. T. & Gordon J. I. Getting a grip on things: how do communities of bacterial symbionts become established in our intestine? Nat. Immunol. 5, 569–573 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hylckama Vlieg J. E., Veiga P., Zhang C., Derrien M. & Zhao L. Impact of microbial transformation of food on health-from fermented foods to fermentation in the gastro-intestinal tract. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 22, 211–219 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C. et al. Interactions between gut microbiota, host genetics and diet relevant to development of metabolic syndromes in mice. ISME J. 4, 232–241 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cani P. D. et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes 56, 1761–1772 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley R. E., Turnbaugh P. J., Klein S. & Gordon J. I. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature 444, 1022–1023 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cani P. D. et al. Selective increases of bifidobacteria in gut microflora improve high-fat-diet-induced diabetes in mice through a mechanism associated with endotoxaemia. Diabetologia 50, 2374–2383 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy E. F. et al. Composition and energy harvesting capacity of the gut microbiota: relationship to diet, obesity and time in mouse models. Gut 59, 1635–1642 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbaugh P. J., Backhed F., Fulton L. & Gordon J. I. Diet-induced obesity is linked to marked but reversible alterations in the mouse distal gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 3, 213–223 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cani P. D. et al. Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice. Diabetes 57, 1470–1481 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cani P. D. et al. Changes in gut microbiota control inflammation in obese mice through a mechanism involving GLP-2-driven improvement of gut permeability. Gut 58, 1091–1103 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Na Fei L. Z. An opportunistic pathogen isolated from the gut of an obese human causes obesity in germfree mice. ISME J. 7, 880–884 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B. et al. Midlife gene expressions identify modulators of aging through dietary interventions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, E1201–E1209 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knights D., Costello E. K. & Knight R. Supervised classification of human microbiota. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35, 343–359 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segata N. et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 12, R60 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veiga P. et al. Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis fermented milk product reduces inflammation by altering a niche for colitogenic microbes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 18132–18137 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore W. E. & Moore L. H. Intestinal floras of populations that have a high risk of colon cancer. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 3202–3207 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finegold S. M., Attebery H. R. & Sutter V. L. Effect of diet on human fecal flora: comparison of Japanese and American diets. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 27, 1456–1469 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller S. et al. Differences in fecal microbiota in different European study populations in relation to age, gender, and country: a cross-sectional study. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 1027–1033 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Filippo C. et al. Impact of diet in shaping gut microbiota revealed by a comparative study in children from Europe and rural Africa. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 14691–14696 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backhed F. et al. The gut microbiota as an environmental factor that regulates fat storage. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 15718–15723 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backhed F., Manchester J. K., Semenkovich C. F. & Gordon J. I. Mechanisms underlying the resistance to diet-induced obesity in germ-free mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 979–984 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley R. E. et al. Obesity alters gut microbial ecology. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 11070–11075 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mai V., Colbert L. H., Perkins S. N., Schatzkin A. & Hursting S. D. Intestinal microbiota: a potential diet-responsive prevention target in ApcMin mice. Mol. Carcinog. 46, 42–48 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santacruz A. et al. Interplay between weight loss and gut microbiota composition in overweight adolescents. Obesity 17, 1906–1915 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson A. L., Cao W. W., Wang R. F., Lu M. H. & Cerniglia C. E. The effect of food restriction on the composition of intestinal microflora in rats. Exp. Gerontol. 33, 239–247 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleessen B., Sykura B., Zunft H. J. & Blaut M. Effects of inulin and lactose on fecal microflora, microbial activity, and bowel habit in elderly constipated persons. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 65, 1397–1402 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostan R. et al. Immunosenescence and immunogenetics of human longevity. Neuroimmunomodulation 15, 224–240 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guigoz Y., Dore J. & Schiffrin E. J. The inflammatory status of old age can be nurtured from the intestinal environment. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 11, 13–20 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flint H. J., Duncan S. H., Scott K. P. & Louis P. Interactions and competition within the microbial community of the human colon: links between diet and health. Environ. Microbiol. 9, 1101–1111 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zareie M. et al. Probiotics prevent bacterial translocation and improve intestinal barrier function in rats following chronic psychological stress. Gut 55, 1553–1560 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardeau M., Guguen M. & Vernoux J. P. Beneficial lactobacilli in food and feed: long-term use, biodiversity and proposals for specific and realistic safety assessments. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 30, 487–513 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price L. B. et al. Community analysis of chronic wound bacteria using 16S rRNA gene-based pyrosequencing: impact of diabetes and antibiotics on chronic wound microbiota. PLoS One 4, e6462 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyuncu M., Acuner I. C. & Uyar M. Deep neck infection due to Lactococcus lactis cremoris: a case report. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 262, 719–721 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehbacher T. et al. Intestinal TM7 bacterial phylogenies in active inflammatory bowel disease. J. Med. Microbiol. 57, 1569–1576 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L. et al. A marker of endotoxemia is associated with obesity and related metabolic disorders in apparently healthy Chinese. Diabetes Care 33, 1925–1932 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweigner J., Schumann R. R. & Weber J. R. The role of lipopolysaccharide-binding protein in modulating the innate immune response. Microbes Infect. 8, 946–952 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T. & Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol. 11, 373–384 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett E. L. & Richardson D. S. Sex differences in telomeres and lifespan. Aging Cell 10, 913–921 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markle J. G. et al. Sex differences in the gut microbiome drive hormone-dependent regulation of autoimmunity. Science 339, 1084–1088 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morell V. Zeroing in on how hormones affect the immune system. Science 269, 773–775 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M. et al. Symbiotic gut microbes modulate human metabolic phenotypes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 2117–2122 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson G. R. Dietary modulation of the human gut microflora using the prebiotics oligofructose and inulin. J. Nutr. 129, 1438s–1441s (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naughton P. J., Mikkelsen L. L. & Jensen B. B. Effects of nondigestible oligosaccharides on Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium and nonpathogenic Escherichia coli in the pig small intestine in vitro. Appl. Environ. Microb. 67, 3391–3395 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T. et al. Structural segregation of gut microbiota between colorectal cancer patients and healthy volunteers. ISME J. 6, 320–329 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulies M. et al. Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature 437, 376–380 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna P. et al. The macaque gut microbiome in health, lentiviral infection, and chronic enterocolitis. PLoS Pathog. 4, e20 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogin M. L. et al. Microbial diversity in the deep sea and the underexplored "rare biosphere". Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 12115–12120 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C. et al. Structural resilience of the gut microbiota in adult mice under high-fat dietary perturbations. ISME J. 6, 1848–1857 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporaso J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7, 335–336 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huse S. M. et al. Exploring microbial diversity and taxonomy using SSU rRNA hypervariable tag sequencing. PLoS Genet. 4, e1000255 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures S1-S9, Supplementary Tables S1-S7, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References