Abstract

Purpose

Fusion of the TMPRSS2 prostate-specific gene with the ERG transcription factor is a putatively oncogenic gene rearrangement that is commonly found in prostate cancer tissue from men undergoing prostatectomy. However, the prevalence of the fusion was less common in TURP samples from a Swedish cohort of incidental prostate cancer patients followed by watchful waiting, raising the question as to whether the high prevalence in prostatectomy specimens reflects selection bias. We sought to determine the prevalence of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion among PSA-screened men undergoing prostate biopsy in the United States.

Experimental design

We studied 140 prostate biopsies from the same number of patients for TMPRSS2-ERG fusion status with a FISH assay. 134 (100 cancer and 34 benign) were assessable.

Results

ERG gene rearrangement was detected in 46% prostate biopsies that were found to have prostate cancer and in 0% of benign prostate biopsies (p<0.0001). Evaluation of morphological features showed that cribriform growth, blue-tinged mucin, macronucleoli and collagenous micronodules were significantly more frequent in TMPRSS2-ERG fusion positive prostate cancer biopsies than gene fusion negative prostate cancer biopsies (p≤0.04). No significant association with Gleason score was detected. In addition, non-Caucasian patients were less likely to have positive fusion status (p=0.02).

Conclusions

This is the first prospective North American multi-center study to characterize the TMPRSS2-ERG prostate cancer prevalence in a cohort of patients undergoing needle biopsy irrespective of whether or not they subsequently undergo prostatectomy. Our results show that this gene rearrangement is common among North American men who have prostate cancer on biopsy, is absent in benign prostate biopsy, and is associated with specific morphological features. These findings indicate a need for prospective studies to evaluate the relationship of TMPRSS2-ERG rearrangement with clinical course of screening-detected prostate cancer in North American men, and development of non-invasive screening tests to detect TMPRSS2-ERG rearrangement.

Introduction

Since its initial discovery (1), the prevalence of TMPRSS2-ERG prostate cancer was reported to vary. In a German cohort where prostatectomy specimens were studied, this approached 50% whereas in an incidental watchful-waiting cohort from Sweden, the prevalence was close to 15% in transurethral resection of prostate (TURP) samples (2, 3). A subsequent study from Portugal confirmed 50% of TMPRSS2-ERG prostate cancer in patients who underwent radical prostatectomy for clinically localized disease (4). In more recent publications from Canada and the United States, the prevalence in prostatectomies ranges between 36% (including all Gleason scores) and 54%, respectively (5, 6). A question has been raised as to whether the high prevalence in prostatectomy specimens is due to selection bias or genetic differences between populations. Further, systematic studies documenting the prevalence of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion in North American cohorts undergoing prostate biopsy are lacking.

In the United States, approximately 1,300,000 prostate biopsies are performed each year, and only in 2006, 234,460 new cases of prostate cancer were diagnosed (American Cancer Society, Cancer facts & figures 2006). The American Cancer Society estimates that 186,320 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer in 2008 and about 28,660 will die from it, making it the most common noncutaneous cancer and the second most lethal cancer amont men in the United States (American Cancer Society, Cancer facts & figures 2008). Emerging data suggests that TMPRSS2-ERG prostate cancer has a worse prognosis. Specifically, higher tumor stage and tumor-specific death or metastases have been documented (2, 3, 6–8).

The purpose of this study was to assess the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion status among PSA-screened men undergoing prostate biopsy in the United States. Given the most recent advances in the evolving story of TMPRSS2-ERG prostate cancer, our work may impact the clinical management of patients with fusion positive prostate cancer detected on needle biopsies.

Materials and Methods

Cohort selection

The analysis involved 140 consecutive patients enrolled in the IRB-approved Early Detection Research Network (EDRN) study from five separate urological practices in Massachusetts and Michigan. Eligible patients were men referred for consideration of prostate biopsy due to either abnormal rectal exam or elevated PSA, or clinical suspicion of prostate cancer. The biopsy paraffin blocks were available for analysis and all corresponding H&E stained slides (three slides per paraffin block) were reviewed. A representative slide from each patient was selected for evaluation of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) (see below). Of the 140 total evaluated biopsy subjects, available histology tissue from 6 was non-assessable by FISH. Of the remaining 134 subjects’ biopsy samples, 100 had prostate cancer and 34 were exclusively benign. The latter included 25 benign biopsies from subjects without prostate cancer and 9 benign biopsies from subjects with prostate cancer. Table 1 summarizes the clinical characteristics of the cohort included in the study.

Table 1.

Clinical variables of the cohort of 134 men undergoing prostate needle biopsy at two institutions in the United States.

| Variable | Institution* | All | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Institution 1 BIDMC |

Institution 2 UM |

||

| All patients | 94 (70%) | 40 (30%) | 134 (100%) |

| Age (years) | 65 [60–70] | 61 [54–70] | 64 [58–70] |

| Race+ | |||

| Caucasian | 78 (83%) | 35 (88%) | 113 (84%) |

| Non-Caucasian | 16 (17%) | 5 (12%) | 21 (16%) |

| PSA (ng/mL) | 5.0 [4.0–7.0] | 5.8 [4.7–10.0] | 5.2 [4.0–8.0] |

| Prostate size by TRUS (cc) | 43 [31–57] | 43 [30–56] | 43 [30–57] |

| PSA density (ng/mL/cc) | 0.12 [0.08–0.19] | 0.13 [0.09–0.24] | 0.12 [0.08–0.19] |

| Number of cores taken | 12 [12–12] | 12 [12–12] | 12 [12–12] |

| Number of cores involved | 2 [1–4] | 10 [1–12] | 2 [1–6] |

| Percent of cores involved | 17 [8–33] | 77 [8–100] | 17 [8–50] |

| Prostate cancer diagnosis | |||

| No | 17 (18) | 8 (20) | 25 (19) |

| Yes | 77 (82) | 32 (80) | 109 (81) |

| Laterality | |||

| Bilateral | 23 (24) | 23 (58) | 46 (34) |

| Left | 25 (27) | 2 (5) | 27 (20) |

| Right | 28 (30) | 1 (3) | 29 (22) |

| Unknown | 1 (1) | 6 (16) | 7 (5) |

| No cancer diagnosis | 17 (18) | 8 (20) | 25 (19) |

| Gleason score | |||

| Gleason ≤ 6 | 27 (29) | 13 (33) | 40 (30) |

| Gleason 7 | 39 (41) | 11 (28) | 50 (37) |

| Gleason ≥ 8 | 8 (8) | 7 (18) | 15 (11) |

| Not applicable or Unknown | 20 (21) | 9 (23) | 29 (22) |

BIDMC = Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center; UM = University of Michigan

Abbreviations: PSA = Prostate specific antigen; TRUS = transrectal ultrasound

See Supplemental Table 1 for results on ethnicity by TMPRSS2-ERG fusion status among 100 patients’ prostate cancer-positive biopsy cores

Pathologic analysis

The morphological diagnosis was confirmed on H&E slides (twelve biopsies per patient) by five pathologists (JMM, EMG, SP, RM, and RBS) prior to evaluation of the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion status. All positive cases were acinar prostate cancer. The Gleason score for each case was assessed and the morphological features below were evaluated blinded to the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion status. Evaluation of morphological features was performed by two independent groups composed of two observers each (JMM and SP, and RM and RBS). Common morphological features of prostate cancer were assessed as previously described (9). These included intraluminal features (blue-tinged mucin), nuclear features (macronucleoli), architectural features (intraductal tumor spread, cribriform growth pattern), malignant-specific features (extraprostatic extension, perineural invasion, glomerulations, and collagenous micronodules), histological variants (signet-ring cell features, foamy gland morphology), and comedonecrosis.

Determination of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion status

We have previously described a dual-color interphase break-apart FISH assay to detect the fusion of TMRSS2-ERG (1, 3, 10). Briefly, the two probes used are differentially labeled and span the telomeric and centromeric neighboring regions of the ERG locus. Because the two genes are close together on chromosome 21, a break-apart probe system has demonstrated to be accurate. The centromeric probe RP11-24A11 overlaps the 3’ ERG coding region, and the telomeric probe RP11137J13 localizes to the intervening region between ERG and TMPRSS2. With this system, a nucleus without ERG rearrangement demonstrates two pairs of juxtaposed red and green signals, forming yellow signals. A nucleus with TMPRSS2- ERG fusion through insertion shows split-apart of one juxtaposed red-green signal pair resulting in single red and green signals for the translocated ERG allele, and a still combined (yellow) signal for the non-rearranged ERG allele in each nucleus. If TMPRSS2-ERG fusion occurs through interstitial deletion of genetic material, only two signals are detected in each nucleus: a yellow signal (for the non-rearranged), and a single red signal for the rearranged allele.

The samples were analyzed under a 60× oil immersion objective using an Olympus BX-51 fluorescence microscope equipped with appropriate filters, a CCD (charge-coupled device) camera (Olympus, Center Valley, PA), and the CytoVision FISH imaging and capturing software (Applied Imaging, San Jose, CA). Evaluation of the tests was independently performed by four pathologists, (JMM, SP, RM and RBS). At one institution two pathologists (JMM and SP) evaluated 99 biopsies, and at the other institution two pathologists (RM and RBS) evaluated 41 biopsies. For each biopsy, we attempted to score at least 50 nuclei.

To ascertain consistency between institutions in evaluation of pathology and TMPRSS2-ERG fusion status

A subset of 30 biopsies (16 from Institution 1 and 14 from Institution 2) was exchanged for validation of the results. For each case, one H&E slide and the corresponding FISH slide were sent for evaluation of morphological features, Gleason score and TMPRSS2-ERG fusion status. 26 FISH slides were assessable. Of the 26 pairs of assessable slides exchanged for cross evaluation among pathologists at the two institutions, there was complete agreement on the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion status by FISH in all cases. The fluorescent signals or the remaining 4 cases were faded. Signal enhancing was attempted but excessive background limited the interpretation. After re-cutting these 4 cases to repeat FISH, the initial small foci of cancer were not present for evaluation.

Statistical analysis

Exact binomial 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for prevalence among cancer and benign biopsies and compared using Fisher’s exact test. Among cancer biopsies, associations of clinical, histological and morphological features with TMPRSS2-ERG were assessed with Fisher’s exact and Wilcoxon rank sum tests. A multivariable logistic regression analysis investigated which factors were most strongly associated with TMPRSS2-ERG fusion positive status.

Results

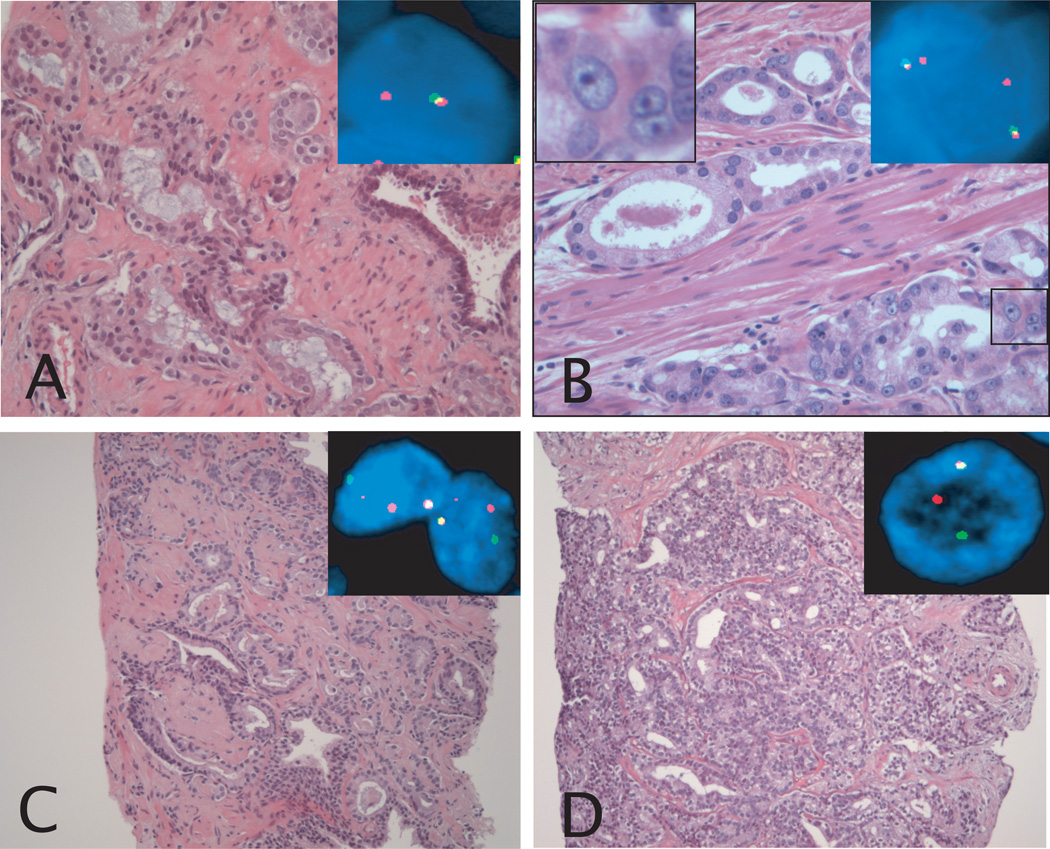

From among the 100 prostate cancer biopsies evaluable by FISH, 46 (46%; 95% CI 36%–56%) demonstrated TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion. In the fusion positive prostate cancers, 63% of cases showed fusion through deletion and 37% showed fusion through insertion. All 34 benign biopsies, which included 9 benign biopsies from patients with prostate cancer, were fusion negative (95% CI 0–10%; P<0.001 vs. cancer biopsies). In addition, normal prostatic glands adjacent to cancer areas in the same biopsy were negative for TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion (Table 2). All histological features were evaluated for their association with TMPRSS2-ERG fusion status. After univariate statistical analysis, the following morphological features were determined to be associated with positive TMPRSS2-ERG fusion status: Cribriform growth (p=0.03), blue-tinged mucin (p<0.01), macronucleoli (p=0.02), and collagenous micronodules (p=0.04). Table 3 summarizes the findings of evaluation of morphological features in all 100 cancer-positive cases, and Figure 1 illustrates those with significant association with TMPRSS2-ERG fusion positive status. The presence of one or more of the above-mentioned morphological features was also associated with a positive TMPRSS2-ERG status, as fusion positive cases had more morphological features noted (P<0.01 for the sum). No significant association was found between Gleason score and TMPRSS2-ERG fusion status (Table 4). When clinical characteristics were analyzed, non-Caucasian patients were less likely to have TMPRSS2-ERG fusion positive prostate cancer (13% vs. 52% fusion positive, P=0.02) (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 2.

TMPRSS2-ERG fusion status of 100 patients’ cancer-positive biopsy cores at the two participating institutions.

| Institution* | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Institution 1 BIDMC |

Institution 2 UM |

|||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| All cores | 71 | 100 | 29 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| TMPRSS2-ERG | 41 | 58 | 13 | 45 | 54 | 54 |

| Negative | ||||||

| Positive | 30 | 42 | 16 | 55 | 46 | 46 |

| All TMPRSS2-ERG positive cores | 30 | 100 | 16 | 100 | 46 | 100 |

| Insertion | 14 | 47 | 3 | 19 | 17 | 37 |

| Deletion | 16 | 53 | 13 | 81 | 29 | 63 |

BIDMC = Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center; UM = University of Michigan

Table 3.

Morphological features by TMPRSS2-ERG fusion status in 100 patients’ prostate cancer-positive biopsy cores

| Morphological features | TMPRSS2-ERG status | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | All | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | P-value | |

| All cores | 54 | 100 | 46 | 100 | 100 | 100 | -- |

| Intraductal tumor spread | 3 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 0.62 |

| Cribriform growth pattern | 4 | 7 | 11 | 24 | 15 | 15 | 0.03 |

| Blue-tinged mucin | 8 | 15 | 23 | 50 | 31 | 31 | <0.01 |

| Macronucleoli | 16 | 30 | 25 | 54 | 41 | 41 | 0.02 |

| Foamy gland morphology | 4 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0.12 |

| Collagenous micronodules | 0 | 0 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 0.04 |

| Extraprostatic extension | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | -- |

| Perineural invasion | 6 | 11 | 9 | 20 | 15 | 15 | 0.27 |

| Signet-ring cell feaures | 4 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0.12 |

| Comedonecrosis | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | -- |

| Glomerulations | 3 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 1.0 |

Figure 1.

Morphological features associated with a positive TMPRSS2-ERG fusion status in prostate cancer. A: Prostate cancer Gleason pattern 3 showing blue-tinged mucin. Inset picture shows FISH image of representative nucleus. One yellow and one red signal are present, demonstrating the presence of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion through deletion. B: Prostate cancer Gleason pattern 3 showing macronucleoli. The inset picture in the upper left corner shows the macronucleoli in the boxed area, and the inset picture in the upper right corner shows a FISH image of representative nuclei. One yellow and one red signal are present in each nucleus, demonstrating the presence of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion through deletion. C: Prostate cancer Gleason pattern 4 with collagenous micronodules. Inset pictures shows FISH image of representative nuclei. One yellow, and separate red and green signals are present in each nucleus, demonstrating the presence of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion through insertion. D: Prostate cancer Gleason pattern 4 with cribriform growth pattern. Inset picture shows FISH image of representative nucleus. One yellow and separate red and green signals are present, demonstrating the presence of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion through insertion. Original magnification of H&E images, 20× objective (A and B), and 10× objective (C and D). Original magnification of FISH images, 60× objective.

Table 4.

Number of morphological features and Gleason score by TMPRSS2-ERG fusion status of 100 patients’ prostate cancer-positive biopsy cores.

| TMPRSS2-ERG status fusion | All | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neg | Pos | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | P-value | |

| All cores | 54 | 100 | 46 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Num. morphological features | <0.001 | ||||||

| 0 | 26 | 48 | 6 | 13 | 32 | 32 | |

| 1 | 13 | 24 | 13 | 28 | 26 | 26 | |

| 2 | 9 | 17 | 20 | 43 | 29 | 29 | |

| 3 | 5 | 9 | 6 | 13 | 11 | 11 | |

| 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Gleason Primary | 41 | 76 | 33 | 72 | 74 | 74 | 0.53 |

| 3 | |||||||

| 4 | 13 | 24 | 12 | 26 | 25 | 25 | |

| 5 | - | - | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Gleason Secondary | 25 | 46 | 24 | 52 | 49 | 49 | 0.46 |

| 3 | |||||||

| 4 | 27 | 50 | 22 | 48 | 49 | 49 | |

| 5 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Gleason Sum | 18 | 33 | 19 | 41 | 37 | 37 | 0.89 |

| 6 | |||||||

| 7 | 30 | 56 | 19 | 41 | 49 | 49 | |

| 8 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 15 | 11 | 11 | |

| 9 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | |

Multivariable analysis demonstrated that lower PSA density, cribiform growth pattern, blue-tinged mucin and macronucleoli were most strongly associated with TMPRSS2-ERG fusion status (Table 5). None of the aforementioned significant associations with positive TMPRSS2-ERG fusion status correlated with the mechanism of gene rearrangement, either through deletion or through insertion. Although not systematically sought, FISH identified four cases of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion HGPIN that shared the same fusion pattern with the prostate cancer in the same biopsy, and three cases of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion heterogeneity in prostate cancer, corresponding to separate areas of tumor within the same tissue core.

Table 5.

Multivariable logistic regression of positive TMPRSS2-ERG fusion status among 100 patients’ prostate cancer-positive biopsy cores.

| Parameter | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSA Density (ng/mL/cc) | 0.050 | ||

| Quartile 1, < 0.09 | 8.01 | (1.8, 36.8) | |

| Quartile 2, 0.09 to <0.15 | 5.7 | (1.3, 26.0) | |

| Quartile 3, 0.15 to <0.2 | 5.3 | (1.1, 26.1) | |

| Quartile 4, ≥ 0.20 | 1 (ref) | ||

| Cribriform growth pattern | 9.4 | (2.3, 38.6) | 0.002 |

| Blue-tinged mucin | 11.6 | (3.4, 39.4) | <.0001 |

| Macronucleoli | 5.3 | (1.3, 22.1) | 0.022 |

Abbreviations: PSA=prostate specific antigen; CI=confidence interval

Discussion

The high prevalence of TMPRSS2-ERG prostate cancer is clinically relevant since emerging data suggests a worse prognosis of tumors harboring the gene fusion. Several studies have demonstrated that TMPRSS2-ERG fusion prostate cancer is associated with higher tumor stage and tumor-specific death or metastasis (2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 11). One of the most relevant studies included men diagnosed with clinically localized prostate cancer in the pre-PSA era and followed with expectant management. In that study we observed that the presence of the TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion was associated with either the development of prostate cancer metastases or prostate cancer specific death after up to 22 years of clinical follow up (2). More recently, Attard et al have described extremely poor cause-specific survival in patients whose prostate cancers demonstrate duplication of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion and interstitial deletion of sequences 5’ to ERG, during an 8-year follow-up (7).

In the current study of a PSA-screened U.S. cohort, we demonstrate that TMPRSS2-ERG fusion prostate cancer has a prevalence of 46% in prostate needle biopsies, similar to that observed in radical prostatectomy specimens (3–6). Therefore, the higher prevalence of TMPRSS2-ERG prostate cancer observed in prostatectomy specimens from Portugal, Germany, and the United States (3–6) compared to transurethral prostate tissue from Sweden and United Kingdom (2, 7) is probably due to the high frequency of clinically insignificant tumors in the latter, and not due to genetic differences in the populations. In fact, 71 prostate biopsies with cancer from Sweden assessed by FISH demonstrated a 45% prevalence of TMPRSS2-ERG prostate cancer with the same distribution of mechanism of gene rearrangement seen in our study, that is 62.5% of cases through deletion and 37.5% of cases through insertion (12).

We have previously described five morphological features associated with TMPRSS2-ERG fusion prostate cancer (9). In the current study, cribriform growth pattern, blue-tinged mucin and macronucleoli were confirmed to be associated with a positive fusion status. The presence of collagenous micronodules that previously did not result as independently significant (p = 0.056) (9) has now been associated with TMPRSS2-ERG fusion prostate cancer. In the most recent USCAP meetings there have been controversial findings regarding the morphologic correlates of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion prostate cancer. Fine et al did not find any correlation (13) and Nigwekar et al found a significant association between perineural invasion, blue-tinged mucin and intraductal tumor spread with a positive gene fusion status (14).

The cross evaluation of the FISH assay by two independent groups of pathologists showed complete agreement. Minor discrepancies in Gleason grading and presence or absence of morphological features were observed. However, only one H&E slide of the 30 cases was available. This certainly limited the complete evaluation of each case, which included up to 12 core biopsies. Hence, FISH and morphological evaluation of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion prostate cancer could potentially be standardized. A future study will focus on the validation of these findings.

Although out of the scope of this manuscript, we identified four cases of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion HGPIN that shared the same fusion pattern with the prostate cancer in the same biopsy, and three cases of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion heterogeneity, corresponding to separate areas of prostate cancer within the same tissue core (data not shown). These observations are consistent with the most recent work on TMPRSS2-ERG fusion HGPIN and TMPRSS2-ERG fusion prostate cancer heterogeneity by our group and others (5, 15, 16). TMPRSS2-ERG interfocal clonal heterogeneity occurs in 41% of prostate cancers that are at least pT2c (15). Hence, FISH analysis would be necessary in bilateral prostate cancer positive cores if one result was negative. We have also demonstrated that TMPRSS2-ERG gene rearrangement, observed in approximately 20% of HGPIN lesions (4, 10, 16), is always indicative of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion prostate cancer (16).

Given their significant clinical implication, these are findings that merit consideration when TMPRSS2-ERG fusion status assessment on prostate biopsies is implemented, and in view of the development of a urine-based screening test for fusion transcripts (17–19).

Clinically, two factors may play a significant role in predicting the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion status in prostate cancer, race and PSA density. Non-Caucasian patients were less likely to have positive fusion status, and this association was significant (p=0.02). Preliminary data from a collaborative study with our group (20) including a larger number of Non-Caucasians show that TMPRSS2-ERG fusion prostate cancer is more common in Caucasians compared to African American and Asian patients (p=0.034). Further, the mechanism of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion through deletion, which has been associated with worse prognosis (2), is more common in prostate cancer of African American patients (p=0.098).

Interestingly, we have seen that one of the best predictors for a positive TMPRSS2-ERG fusion status is a lower PSA density (Table 5).

In summary, we have assessed the TMPRSS2-ERG fusion status in a large series of prostate needle core biopsies in the United States. We have confirmed prevalence similar to previously reported series in prostatectomy specimens and also confirmed morphological features of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion positive prostate cancer.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Translational Relevance.

The high prevalence of TMPRSS2-ERG prostate cancer is clinically relevant since emerging data suggests a worse prognosis of tumors harboring the gene fusion (i.e. higher tumor stage and tumor-specific death or metastasis). Prevalence of the TMPRSS2-ERG gene rearrangement in the U.S. has previously been described only in single-institution studies of archival, retrospective tissue banks comprised of prostate cancer tissue from patients who underwent prostatectomy (and less than 35% of prostate cancer diagnosed in the U.S. is treated by prostatectomy). Thus, the actual prevalence of this fusion event among the entire spectrum of biopsy-confirmed prostate cancers in the U.S. population is lacking, and no American multi-center data regarding this gene alteration has been described. In the current study of a PSA-screened U.S. cohort, we demonstrate that TMPRSS2-ERG fusion prostate cancer has a prevalence of 46% in prostate needle biopsies and show morphological features associated with the gene fusion. Our findings: 1) validate the feasibility of measuring TMPRSS2-ERG fusion in routine, clinical prostate biopsy samples; 2) demonstrate histo-morphological consequences of the gene rearrangement, and 3) provide a benchmark of the TMPRSS2-ERG rearrangement prevalence in a multi-center, U.S. cohort that reflects the spectrum of prostate cancer diagnosed in the U.S.

Acknowledgments

Research funded by NCI EDRN (NIH U01-CA11391, M. Sanda, PI), and supported by the NIH Prostate SPORE at the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center NCI P50 CA090381(MA Rubin), R01AG21404 (MA Rubin), German Research Foundation Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft DFG# PE1179/1-2 (S Perner), Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Training Award PC061474, and the NIH Grant UO1 CA 113913 for the BID EDRN (Harvard/Michigan Prostate Cancer Clinical Center). The authors are grateful to Christopher Lafargue for technical support critical to this study.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 97th Annual Meeting of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology in Denver, CO, March 2008, and at the Annual Meeting of the American Urological Association in Orlando, May 2008

References

- 1.Tomlins SA, Rhodes DR, Perner S, et al. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science. 2005;310(5748):644–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1117679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Demichelis F, Fall K, Perner S, et al. TMPRSS2:ERG gene fusion associated with lethal prostate cancer in a watchful waiting cohort. Oncogene. 2007;26(31):4596–4599. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perner S, Demichelis F, Beroukhim R, et al. TMPRSS2:ERG fusion-associated deletions provide insight into the heterogeneity of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66(17):8337–8341. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cerveira N, Ribeiro FR, Peixoto A, et al. TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion causing ERG overexpression precedes chromosome copy number changes in prostate carcinomas and paired HGPIN lesions. Neoplasia. 2006;8(10):826–832. doi: 10.1593/neo.06427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehra R, Tomlins SA, Shen R, et al. Comprehensive assessment of TMPRSS2 and ETS family gene aberrations in clinically localized prostate cancer. Mod Pathol. 2007;20(5):538–544. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajput AB, Miller MA, De Luca A, et al. Frequency of the TMPRSS2:ERG gene fusion is increased in moderate to poorly differentiated prostate cancers. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60(11):1238–1243. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.043810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Attard G, Clark J, Ambroisine L, et al. Duplication of the fusion of TMPRSS2 to ERG sequences identifies fatal human prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27(3):253–263. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nam RK, Sugar L, Yang W, et al. Expression of the TMPRSS2:ERG fusion gene predicts cancer recurrence after surgery for localised prostate cancer. Br J Cancer. 2007;97(12):1690–1695. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mosquera JM, Perner S, Demichelis F, et al. Morphological features of TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusion prostate cancer. J Pathol. 2007;212(1):91–101. doi: 10.1002/path.2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perner S, Mosquera JM, Demichelis F, et al. TMPRSS2-ERG fusion prostate cancer: an early molecular event associated with invasion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31(6):882–888. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213424.38503.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Cai Y, Ren C, Ittmann M. Expression of variant TMPRSS2/ERG fusion messenger RNAs is associated with aggressive prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66(17):8347–8351. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Svensson M, Perner S, Demichelis F, et al. USCAP. Boston, MA: 2009. Frequency of ERG Rearrangement in a Swedish Hospital Based Biopsy Cohort. Abstract 885. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fine S, Gopalan A, Leversha M, et al. USCAP. San Diego, CA: 2007. Are there morphologic correlates of prostate cancer associated with TMPRSS2-ERG molecular abnormalities? Abstract 659. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nigwekar P, Miick S, Rittenhouse H, et al. USCAP. Denver, CO: 2008. Morphologic correlates of individual splice variants of TMPRSS2-ERG prostate cancer (PCa) detected by transcription-mediated amplification (TMA) in radical prostatectomy (RP) specimens. Abstract 797. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barry M, Perner S, Demichelis F, Rubin MA. TMPRSS2-ERG fusion heterogeneity in multifocal prostate cancer: clinical and biologic implications. Urology. 2007;70(4):630–633. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.08.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mosquera JM, Perner S, Genega EM, et al. Characterization of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and potential clinical implications. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(11):3380–3385. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hessels D, Smit FP, Verhaegh GW, Witjes JA, Cornel EB, Schalken JA. Detection of TMPRSS2-ERG fusion transcripts and prostate cancer antigen 3 in urinary sediments may improve diagnosis of prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(17):5103–5108. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laxman B, Morris DS, Yu J, et al. A first-generation multiplex biomarker analysis of urine for the early detection of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68(3):645–649. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laxman B, Tomlins SA, Mehra R, et al. Noninvasive detection of TMPRSS2:ERG fusion transcripts in the urine of men with prostate cancer. Neoplasia. 2006;8(10):885–888. doi: 10.1593/neo.06625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou M, Simmerman K, Tsuzuki T, et al. USCAP. Boston, MA: 2009. TMPRSS2-ERG Gene Fusion in Prostate Cancer of Different Ethnic Groups. Abstract 925. 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.