Abstract

We synthesized 5-allyl-1-methyl-5-(m-trifluoromethyl-diazirynylphenyl)barbituric acid (14), a trifluoromethyldiazirine-containing derivative of general anesthetic mephobarbital, separated the racemic mixture into enantiomers by chiral chromatography, and determined the configuration of the (+)-enantiomer as S by x-ray crystallography. Additionally, we obtained the 3H-labeled ligand with high specific radioactivity. R-(−)-14 is an order of magnitude more potent than the most potent clinically used barbiturate, thiopental, and its general anesthetic EC50 approaches those for propofol and etomidate, whereas S-(+)-14 is tenfold less potent. Furthermore, at concentrations close to its anesthetic potency, R-(−)-14 both potentiated GABA-induced currents and increased the affinity for the agonist muscimol in human α1β2/3γ2L GABAA receptors. Finally, R-(−)-14 was found to be an exceptionally efficient photolabeling reagent, incorporating into both α1 and β3 subunits of human α1β3 GABAA receptors. These results indicate R-(−)-14 is a functional general anesthetic that is well-suited for identifying barbiturate binding sites on Cys-loop receptors.

Introduction

Derivatives of barbituric acid (pyrimidine-2,4,6(1H,3H,5H)-trione) were amongst the first synthetic, clinically used pharmacological agents with 5,5-diethylbarbituric acid introduced by Bayer as early as in 1903, followed by 5-ethyl-5-phenylbarbituric acid in 1912.1 Several thousand barbiturates have been synthesized and tested as clinical agents,2 and some are still in clinical use today.3–4 They have applications as anxiolytics, sedatives, anesthetics and antiepileptics. Barbiturates affect a wide variety of neuronal ion channels, with the most prominent effects being on the Cys-loop receptors (GABAA, nACh), the AMPA and kainite receptors.5–6 The multiplicity of their biological actions makes understanding their mechanisms in molecular terms a challenging issue. Although activity tends to increase with hydrophobicity, small changes in their chemical structure can radically alter action on the CNS. For example, adding a single methyl group to the general anesthetic pentobarbital (5-ethyl-5-(pentan-2-yl)pyrimidine-2,4,6(1H,3H,5H)-trione) produces the convulsant DMBB (5-ethyl-5-(4-methylpentan-2-yl)pyrimidine-2,4,6(1H,3H,5H)-trione).7–9 Such sensitivity to small changes in barbiturate chemical structure implies there are specific barbiturate binding sites as evidenced by saturable and stereospecific binding of radiolabeled pentobarbital to nACh receptor.10

The precise location of the barbiturate binding sites on their molecular targets still remains unknown. In one study of anesthetic action, knock-in mice with a N265M mutation in the GABAA receptor β3 subunit11 displayed insensitivity to pentobarbital, as well as etomidate and propofol,12 demonstrating that β3-containing GABAA receptors are responsible for anesthetic action. This same mutation also affected etomidate– and propofol–induced respiratory depression, but not that of pentobarbital, hinting at different modes of action.12 The mutational approach, however, does not distinguish whether the β3N265 residue is involved in barbiturate binding, or is only participating in conformational transitions between the receptor states. Indeed, the binding sites of pentobarbital and other common anesthetics such as alcohols, steroids, volatile agents, and propofol, are also thought to be distinct.13,14

The development of photo-reactive general anesthetics provides a powerful approach to identify the amino acids contributing to anesthetic binding sites in mammalian GABAA receptors.15–19 Using this approach, a binding site for etomidate has been identified in the GABAA receptor transmembrane domain at the interface between α and β subunits. This site includes the position N265 in βM2 that is a determinant of an anesthetic sensitivity.20,21 The binding sites for barbiturates, as well as propofol and neurosteroids, appear distinct from this etomidate binding site, because these anesthetics act as allosteric modulators of photolabeling at the etomidate site.22,23 To facilitate the identification of the barbiturate binding sites in the GABAA receptors, we have now synthesized a photo-reactive derivative of mephobarbital, 5-allyl-1-methyl-5-(m-trifluoromethyldiazirynylphenyl)barbituric acid (14), and separated its enantiomers. In this report, we describe the synthesis of this new pharmacological probe and an initial characterization of its pharmacology. R-(−)-14 is a powerful general anesthetic that potentiates agonist–induced activation of the α1β2γ2 GABAA receptor, while S-(+)-14 is 10-fold less potent. [3H]R-(−)-14 photoincorporates efficiently into the barbiturate binding site(s) in the expressed human α1β3 GABAAR, as evidenced by the inhibition of photolabeling by pentobarbital and stereospecific inhibition by the unlabeled compound 14.

Results

Synthesis of Diazirine Analogs of Mephobarbital

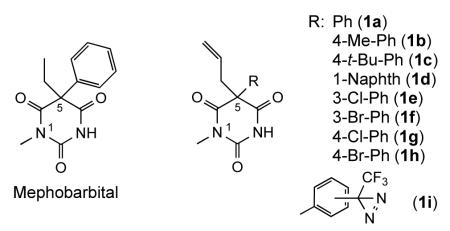

Structural and synthetic design of the photoreactive barbiturate

In order to promote high binding affinity of the photoreactive ligand, we based our initial molecular design on 1-N-methyl barbiturates,2,24 which are more potent than other barbiturates. In the structure of mephobarbital (see below), one of the leading representatives of barbiturates, both 5-ethyl and 5-phenyl groups were predicted to be amenable to modifications by a photoactivatable trifluoromethyldiazirine (TFD) group. We replaced the mephobarbital ethyl group with an allyl moiety for several reasons. First, structure-activity data for mephobarbital indicates the replacement of 5-ethyl with allyl substituent (as in structure 1a) increases the drug potency by a factor of 2.24 Secondly, the presence of an allyl group provides an easy route for introduction of a tritium radiolabel via partial hydrogenation of a triple bond. In addition, modification of the phenyl ring with the TFD moiety should be permissible since substitution of the phenyl ring with small groups (eg. p-methyl in 1b) does not affect barbiturate activity.25 The space available for phenyl ring modification is limited, however, since the p-tert-butylphenyl analog 1c is less potent,25 as is 5-(1-naphthyl) analog 1d.26 A significant activity of meta- and para-halogen substituted derivatives of mephobarbital (1e-1h)27,28 further suggested that attachment of a TFD residue at these positions should be a plausible approach. Finally, we viewed modifications of the phenyl ring with a TFD residue at the meta- and para-positions (1i) more suitable than that at the ortho-position, as they would eliminate potential intramolecular reactions of a photogenerated carbene intermediate with nucleophilic groups of the barbiturate framework. Hence, our synthetic efforts were initially focused on synthesis of the meta- and para-TFD substituted analogs.

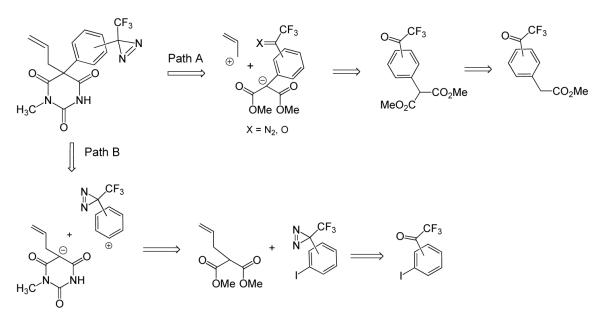

The retrosynthetic analysis revealed two pathways for the synthesis: via trifluoroacetyl derivatives of phenylmalonic acid (Path A) and through arylation of 1-methyl-5-alkylbarbituric derivative (Path B).

The only commercially available precursors for Path A found were simple derivatives of phenylacetic acid, which could not be readily and regioselectively converted into their p- or m-trifluoroacetyl derivatives. Thus, in our hands, ethyl phenylacetate gave a poorly separable 1:1 mixture of m- and p-trifluoroacetyl derivatives under Friedel-Crafts conditions, similarly to the previously described acetylation,29,30 and diethyl phenylmalonate under similar conditions remained unchanged. Trifluoroacetylation of aryllithium derivatives generated from 3- and 4-bromophenylacetic acids31 also proved unsuccessful. Thus, poor availability of key intermediates and relatively long synthesis for Path A suggested trying an alternative, convergent Path B.32

Arylation of dicarbonyl compounds with diaryliodonium salts has been reported previously,33 and the prospective substrates for such arylation pathway, 5-alkylbarbiturates, were readily available through base-catalyzed condensation of 2-alkylmalonic esters with methylurea.2 Indeed, our model reaction of substituted diaryliodonium salts 2 and 3 with 5-allyl barbiturate 4 in DMF (Scheme 2) afforded a 1,5,5-trisubstituted barbiturate 5 in high yield. To avoid a potential instability of the diazirine group during the coupling reaction we applied a non-catalytic (Pd-free) procedure.

Scheme 2.

Substitution with a single 4-methoxy group or three methyl groups at 2-, 4- and 6-positions on one of the aromatic rings in the iodonium salts 2 and 3, respectively, suppressing the transfer of electron-rich aryl group, was used to control the selectivity of the phenyl transfer reaction. We eventually decided to use a methoxy-substituted iodonium salt due to perceived easier separation of a minor side-product 6.

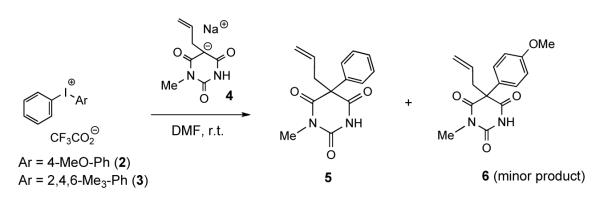

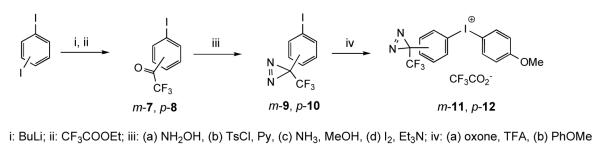

Synthesis of the photoreactive barbiturates

Synthesis of TFD-bearing diaryliodonium salts started from the commercially available m- and p-diiodobenzenes to form the corresponding m- and p-trifluoroacetylarenes m-7 and p-8, respectively, in one step.31,34 The corresponding m- 35 and p-iodophenyl trifluoromethyl diazirines (m-9 and p-10, respectively) were also obtained analogously as described recently.16 The subsequent oxidation of iodophenyl diazirines with oxone in the presence of trifluoroacetic acid,36 followed by the reaction with anisole37 afforded the corresponding unsymmetrical diaryliodonium trifluoroacetates (m-11 and p-12). Interestingly, the m-iodophenyl trifluoromethyl diazirine m-9 underwent complete oxidation in less than two hours (similarly to phenyl iodide), whereas oxidation of p-10 was very sluggish, and the yield of the diaryliodonium product p-12 was significantly lower. Because an alternative oxidation of the para-derivative with m-CPBA38 did not improve the yield of p-12, we decided that the m-substituted iodonium compounds be first used in the further synthesis.

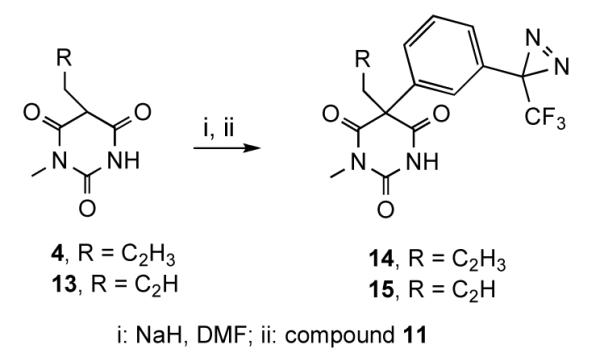

Arylation of the 5-allyl and 5-propargyl-1-methylbarbiturates (4 and 13, respectively) (Scheme 4) proceeded as expected with retention of the TFD group, and afforded the corresponding 5-alkyl-5-aryl-1-methylbarbiturates 14 and 15, respectively, in good yields. The transfer of p-methoxyphenyl group was not detected.

Scheme 4.

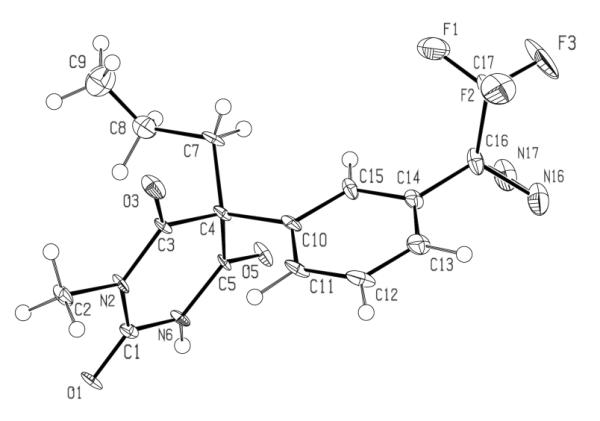

Separation of enantiomers of compound 14 and determination of their absolute configurations

Due to methylation of the nitrogen at the 1-position, the position 5 in compounds 14 and 15 is a center of chirality. Separation of the racemic mixture of 14 into pure enantiomers was accomplished using preparative chiral chromatography on Daicel Chiralpack® AD column, where the levorotatory enantiomer was eluted off first (Supporting Information Figure 1s), similarly to other barbiturates.39 We have subsequently crystallized the dextrorotatory enantiomer, and confirmed its structure and determined its configuration by x-ray crystallography.40 As shown in Figure 1, the slow-eluting (+)-enantiomer of compound 14 has an S-configuration. The crystal structure has been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre and allocated the deposition number CCDC 873393.

Figure 1.

ORTEP drawing of the molecular structure of S-(+)-14.

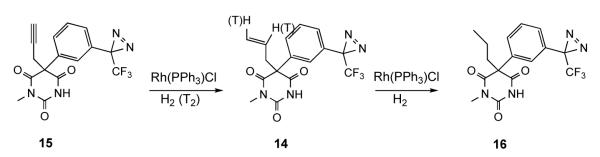

Tritiation of the photoreactive barbiturates

For the site-specific identification of the photolabeled residues of the receptor, tritiated ligands with very high specific radioactivity are necessary. The possibility of radioactive labeling of the compound 14 by partial reduction of the triple bond with tritium gas was explored by catalytic hydrogenation of the propargyl derivative 15 (Scheme 5). The hydrogenation of 15 in the presence of 10% Pd/C catalyst failed to provide the desired product 14 due to the concomitant reduction of the diazirine group under the reaction conditions. Furthermore, attempts to kinetically control partial hydrogenation on Pd/C-triethylamine-methanol or Lindlar catalyst41 were also unsuccessful. In contrast, partial hydrogenation of the propargyl derivative 15 into allyl analog 14, and further complete reduction into the propyl derivative 16, without decomposition of the TFD moiety, was achieved using the Wilkinson’s rhodium catalyst (Scheme 5).42 Formation of an intermediate allyl barbiturate 14 was confirmed by 1H and 19F NMR spectra of the reaction mixture and by TLC (Ag+-impregnated silica gel plates) of reaction mixture and pure 14. The substrate 15 was also readily separable from 14 by the reverse phase HPLC (Supporting Information, Figure 2s). The diazirine moiety proved sufficiently stable under these conditions, thus allowing complete saturation of the triple bond and enabling synthesis of the propyl derivative 16 using larger amounts of catalyst and a longer reaction time.

Scheme 5.

The reduction of the triple to a double bond proceeded much faster than the further saturation of the double bond (5 min vs 3 h). The propyl derivative 15 was also separated into enantiomers using analogous conditions to those of 14, and the “fast”-enantiomer of 15 was found to give rise to “fast”-isomer, R-(−)-14, upon partial reduction. The “fast”-enantiomer of 15 was subsequently reduced commercially by Vitrax Co. to afford [3H]R-(−)-14 with specific radioactivity of 38 Ci/mmol.

Pharmacological Properties

Solubility, partition coefficient and pKa

The saturated aqueous solubility of (±)-14 in 0.01 M Tris/HCl, pH 7.4 was 80 ± 4 μM. At a concentration close to saturation, the compound was stable at 4°C in the aforementioned buffer for at least 2.5 days and eluted as a single fraction at 81.5% acetonitrile when analyzed by reverse phase HPLC. Likewise, the octanol/buffer (pH 7.4) partition coefficient was determined as 6230 ± 250. By measuring the UV absorbance of the compound (±)-14 as a function of pH, the pKa of the NH proton was determined as 7.48±0.08 (Supporting Information, Figure 3s). For comparison, the reported solubility of mephobarbital in water is 0.6 mM, the octanol/water partition coefficient is 69 and pKa is 7.65.43 Thus, our synthesized probe is significantly more hydrophobic than the parent compound, but has very similar acidity.

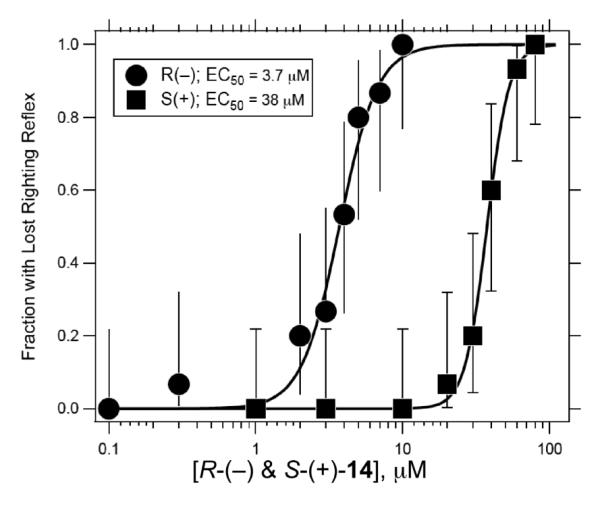

The anesthetic potency of the enantiomers of 14

Anesthetic concentration-response curves were determined as loss of righting reflexes (LoRR) in tadpoles (Figure 2). The concentration ranges used were 0.1 to 10 μM, and 1 to 80 μM, for the R-(−)- and S-(+)-14, respectively. Anesthesia was reversible and all animals recovered within an hour after transfer to fresh water except for one animal that died after exposure to 10 μM of the R-(−)-14. It was excluded from the analysis. The potency of the R-(−)-14 was ten times that of the S-(+)-14 Agent, EC50 μM, Slope, # of animals: R-(−)-14, 3.7 ± 0.25, 3.4 ± 0.8, 119; S-(+)-14, 38 ± 1.4, 5.8 ± 1.3, 120. Errors are standard deviations).

Figure 2.

Enantioselectivity of the effects of barbiturate 14 in general anesthesia. The results for R-(−)-14 and S-(+)-14 are denoted by filled circles and filled squares, respectively. Anesthetic potency was measured by loss of righting reflexes in tadpoles as described in the Experimental Section. Each point represents 15 animals and error bars are binomial 95% confidence limits. Solid lines represent the least squares fitting of the data to the Hill equation.

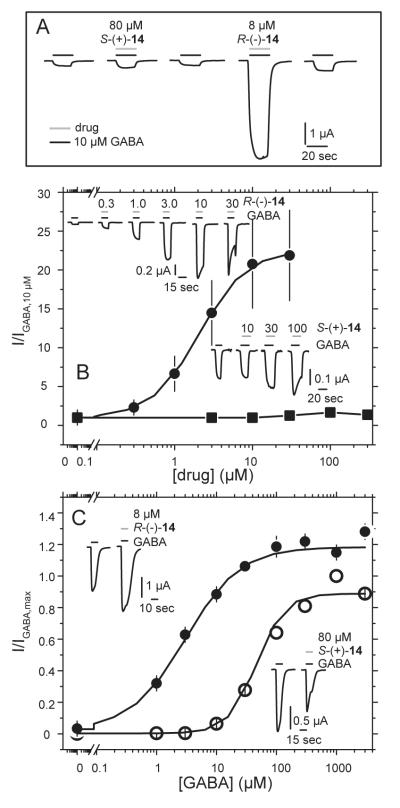

Enhancement of GABAA receptor channel function

Human α1β2γ2L GABAA receptor currents expressed in Xenopus oocytes were dramatically potentiated by R-(−)-14 at a concentration of twice the anesthetic dose, generally considered to represent clinical anesthesia (Figure 3A). At 8 μM R-(−)-14 increased the current response ~19–fold, from 0.25 μA to 4.8 μA. In contrast, in the same oocyte, S-(+)-14 at 80 μM reversibly increased the 10 μM GABA current response by only 1.4–fold. Currents elicited with 10 μM GABA were potentiated with increasing amounts of R-(−)-14 with an EC50 of ~2 μM (Figure 3B). For comparison, pentobarbital at concentrations close to its anesthetic EC50 (65 μM) potentiated 10 μM GABA currents only 4-6 fold.44

Figure 3.

Stereoselective action of R-(−)-14 and S-(+)-14. (A) Two electrode voltage clamp was used to measure currents from oocytes injected with human α1β2γ2L GABAA receptor subunits. Currents were elicited with 10 μM GABA (black bar) and twice the anesthetic dose of each compound sequentially applied to the same oocyte: 80 μM S-(+)-14 or 8 μM R-(−)-14 (grey bars). (B) 10 μM GABA currents were potentiated with increasing amounts of R-(−)-14 or S-(+)-14. Solid lines represent the non-linear least squares fit to the data. For R-(−)-14 (circles): EC50 = 2.1 ± 1.2 μM, nH = 1.4 ± 0.5, Imax = 23 ± 5 (data from 2 oocytes). 10 μM GABA current traces from a typical oocyte are shown in top inset with increasing amounts of R-(−)-14. S-(+)-14 (squares) was tested up to 300 μM (squares) and data could not be similarly fit. Traces from a typical oocyte in lower inset represent 10 μM GABA plus increasing amounts of S-(+)-14. (C) GABA concentration response curves shift to the left in the presence of R-(−)-14. Data is shown from one representative oocyte. Solid lines represent the non-linear least squares fit to the data: for GABA: EC50 = 46 ± 1 μM, nH = 1.8 ± 0.1, Imax = 0.9 ± 0.01 (open circles). In the presence of 8 μM R-(−)-14: EC50 = 3.1 ± 0.1 μM, nH = 1.0 ± 0.1, Imax = 1.2 ± 0.01 (closed circles). Currents were normalized to the maximal GABA response. Current traces in upper inset show the effect of 8 μM R-(−)-14 on 3 mM GABA current responses. Traces in lower inset show effect of 80 μM S-(+)-14 on 1 mM GABA currents.

At maximal concentrations of R-(−)-14 (10 – 30 μM), the current response to 10 μM GABA was enhanced ~25–fold. At 30 μM R-(−)-14, we observed inhibition of the initial response and the rebounding of the current after the removal of the drug. Similar experiments with S-(+)-14 showed only a 1.4–fold increase in current response at 30 μM and 1.8–fold at 100 μM. At concentrations higher than 100 μM, we observed substantial inhibition, making it impossible to obtain enough points to fit the data.

R-(−)-14 shifted the GABA concentration response curve to the left ~15–fold at 8 μM (Figure 3C). At maximal GABA concentrations, 8 μM R-(−)-14 consistently enhanced the current response by ~20%. The effect of 80 μM S-(+)-14 was tested only at 10 μM and 1 mM GABA due to the large amount of material that would be needed to test the whole dose response curve at twice the anesthetic dose (80 μM). At 10 μM GABA, 80 μM S-(+)-14 increased the current 1.4–fold, whereas the 1 mM GABA current was inhibited by 40% at the same concentration of S-(+)-14. The latter contrasted with the 20% increase in current seen with 8 μM R-(−)-14 at maximal GABA responses (current traces in Figure 3C).

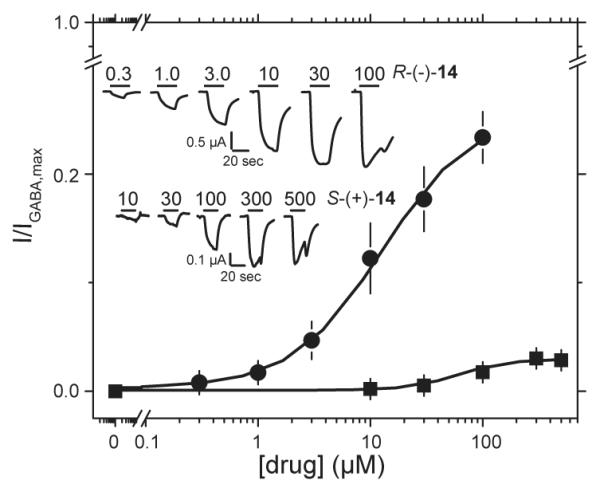

Both drugs were able to directly activate GABA receptors (Figure 4). R-(−)-14 evoked currents equal to ~25% of the maximal GABA response with an EC50 of ~12 μM. In contrast, S-(+)-14 evoked currents that were only 3% of the maximal GABA response with an EC50 of 61 μM.

Figure 4.

Direct activation of α1β3γ2L GABAA receptor with the enantiomers of barbiturate 14. Currents were elicited with increasing amounts of drug. With the exception of not using GABA, all conditions were the same as in Figure 3. Upper and lower traces show current responses to the stated concentrations of R-(−)-14 and S-(+)-14. For R-(−)-14 (circles): EC50 = 13 ± 8 μM, nH = 1.1 ± 0.4, Imax = 26 ± 5% (4 oocytes). For S-(+)-14 (squares): EC50 = 61 ± 6 μM, nH = 1.9 ± 0.2, Imax = 3 ± 0.1 % (one oocyte due to amount of material required). For least squares analysis, currents were normalized to the maximal GABA response for each oocyte.

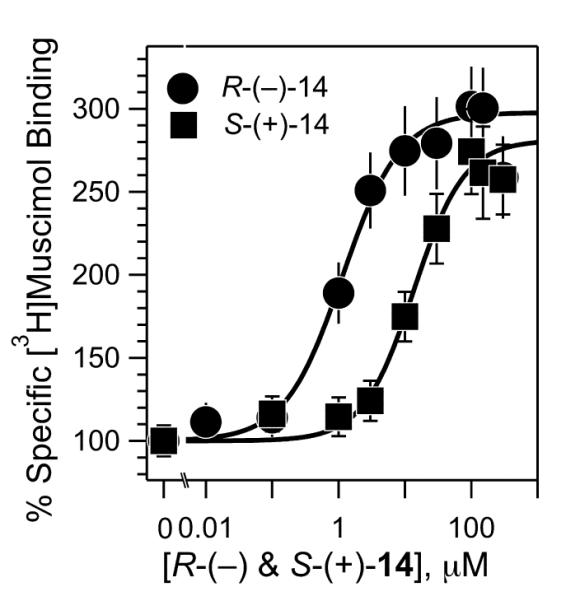

Enantiomer-specific allosteric regulation of GABAA receptor agonist binding

Both R-(−)- and S-(+)-14 enhanced specific binding of the agonist [3H]muscimol, to human α1β3γ2L GABAAR membranes from HEK293 cells in a concentration–dependent manner until reaching a plateau at 2.5– and 3–fold enhancement, respectively (Figure 5). For R-(−)-14 the effect leveled off at ~10 μM, and for S-(+)-14 at ~100 μM. When the concentration–modulation curves were fitted to a logistic equation by nonlinear least squares, a 12–fold enantioselectivity in their half-effect concentrations was revealed, with EC50 values of 1.2 ± 0.12 μM and 14.1 ± 1.5 μM for R-(−)-14 and S-(+)-14 respectively. This ~10–fold difference is comparable to that for general anesthesia determined in tadpoles (Figure 2).

Figure 5.

Comparison of the enantioselectivity of 14 for enhancement of agonist binding to GABAARs expressed as percent enhancement by 14 of specifically bound [3H]muscimol. R-(−)- and S-(+)-14 are denoted by filled circles and filled squares, respectively. R-(−)- and S-(+)-14 were incubated with human α1β3γ2L GABAAR membranes from HEK293 cells in the presence of 2 nM [3H]muscimol. Non-specific binding was measured in the presence of 1 mM GABA. Error bars represent propagated errors calculated from standard deviations of 8-12 independent filtrations from two or three independent incubations at each concentration. Solid lines represent the least squares fitting of the data to the Hill equation.

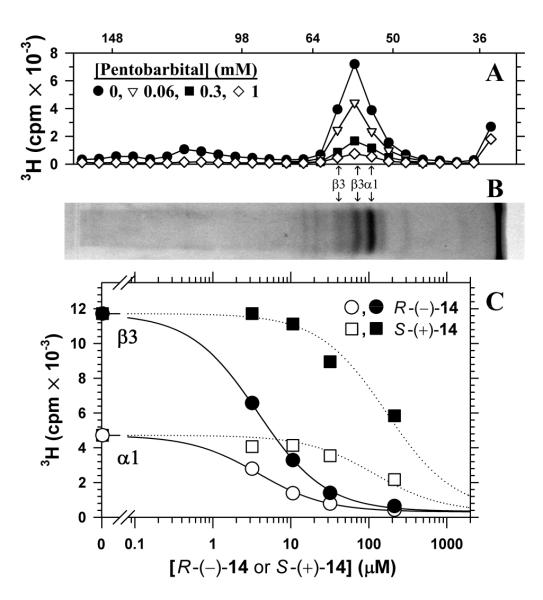

Photoincorporation into purified human α1β3 GABAAR

To determine whether [3H]R-(−)-14 is a useful photoaffinity reagent for the identification of barbiturate binding sites on GABAA receptors, we photoincorporated it, in the absence or presence of non-radioactive barbiturates, into a purified FLAG-α1β3 GABAAR that is known to contain a binding site for etomidate and photoreactive etomidate analogs.21,45 Photoincorporation was characterized by SDS-PAGE and liquid scintillation counting of excised gel bands (Figure 6). When the polypeptides in this purified GABAAR were resolved by SDS-PAGE, Coomassie Blue staining of the gel revealed a prominent band of 56 kDa and more weakly stained bands of 59 and 61 kDa (Figure 6A and B). N-Terminal sequence analyses has identified the 56 kDa band as the FLAG-α1 subunit, and the 59 and 61 kDa bands contained β3 subunits, differing by the glycosylation status of β3 Asn-8.21 In the absence of competing non-radioactive barbiturate, [3H]R-(−)-14 was photoincorporated into the gel bands containing the α1 and both β3 subunits, with 2-3–fold more incorporation in the β3 subunit than in the α1 subunit. Pentobarbital produced a concentration–dependent inhibition of photoincorporation in the β3 and α1 subunits, each with IC50 = 88 ± 8 μM, and 1 mM pentobarbital reduced subunit photolabeling by ≥90%. (Figure 6A). The binding of 14 to the photolabeled binding site was strongly stereospecific. Non-radioactive R-(−)-14 at 200 μM inhibited β3 and α1 subunit photolabeling by ≥90%, with IC50 values of 3.9 ± 0.6 μM and 3.8 ± 0.3 μM, respectively (Figure 6C). In contrast, S-(+)-14 inhibited β3 and α1 subunit photolabeling by only ~60%. IC50 values of 170 ± 30 μM (β3) and 120 ± 30 μM (α1) were calculated with the assumption that S-(+)-14 at higher concentrations would inhibit photolabeling to the same extent as R-(−)-14. Based upon the specific radiochemical activity of [3H]R-(−)-14 (38 Ci/mmol or 33,440 cpm/pmol) and the amount of GABAAR loaded onto each gel lane (~4 pmol of [3H]muscimol binding sites on α1 and β3 subunits), the barbiturate-inhibited incorporation into the β3 (11,400 cpm) and α1 (4,400 cpm) subunits indicates that ~9% of β3 and 3% of α1 subunits were photolabeled. This photolabeling efficiency of α1β3 GABAAR is 10-fold higher than that seen for diazirine analogs of etomidate.21

Figure 6.

Photolabeling of human α1β3 GABAAR with [3H]R-(−)-14 and concentration-dependent, stereospecific inhibition of photolabeling by non-radioactive barbiturates. Aliquots of purified human α1β3 GABAAR (~4 pmol [3H]muscimol sites in 180 μL final volume), equilibrated with 1 mM GABA, 0.3 μM [3H]R-(−)-14 (~2 μCi), and various concentrations of pentobarbital (A and B), R-(−)-14 (C), or S-(+)-14 (C), were irradiated (365 nm UV) for 30 min, and then GABAAR receptor subunits were isolated by SDS-PAGE as described in the Methods. A, 3H gel slice analysis (4 mm slices) of samples labeled in the presence of various concentrations of pentobarbital, with one of the Coomassie Blue-stained gel lanes shown in B. The migration of the molecular mass standards are indicated above the graph, and the known positions of the GABAAR α1 and β3 subunits21 are indicated below the graph with reference to the Coomassie Blue stained gel. For analysis of the concentration dependence of inhibition, the cpm in the single gel band containing the α1 subunit or the combined cpm in the two gel bands containing the β3 subunits were fit to a single site model (see Methods). Pentobarbital inhibited photolabeling of both the α1 and β3 subunits with IC50 = 88 ± 8, respectively, and background (bkg) values of 390 ± 110 cpm and 290 ± 255 cpm. C, Non-radioactive R-(−)-14 (●,○) inhibited [3H]R-(−)-14 incorporation into the α1 (○) and β3 (●) subunits with IC50 values of 3.8 ± 0.3 μM and 3.8 ± 0.2 μM, respectively, and bkg values of 310 ± 65 cpm and 330 ± 100 cpm. S-(+)-14 (■,□) inhibited α1 (□) and β3 (■) subunit photolabeling with IC50 values of 120 ± 30 μM and 170 ± 30 μM, respectively (dotted lines), with the values of bkg for each subunit fixed at those determined from the fit of the R-(−)-14 data.

Discussion

We have synthesized a photoactivatable analog of mephobarbital that shows all the hallmarks of a typical barbiturate modulator of GABAA receptor, but is characterized by significantly greater potency, efficacy and stereoselectivity as compared to previously described barbiturate drugs. Our synthetic photoprobe R-(−)-14 is more potent than any of the 15 barbiturates characterized using tadpole loss of righting reflex, a standard assay for obtaining equilibrium potencies unperturbed by pharmacodynamics.24 In that screen, methohexital (mixture of four stereoisomers) had an EC50 of 20 μM. Methohexital shares with R-(−)-14 the 1-methyl and 5-allyl groups, but differs in the structure of the second 5-substituent (hex-3-yne-2-yl in methohexital) and the presence of another chiral center at the hex-3-yne-2-yl substituent. The results from that study also indicated that introduction of the 1-methyl group increases the potency by ~30 fold (e.g. phenobarbital EC50 = 3.3 mM vs mephobarbital EC50 = 90 μM) and that the 5-ethyl to 5-allyl substitution tends to increase potency 2-fold (pentobarbital vs. secobarbital; thiopental vs. thiamylal).24 The above comparisons indicate that addition of the mTFD-moiety into the phenyl ring (in R-(−)-14) enhanced potency ~6-fold.

The presence of chirality in barbiturate 14 adds the absolute configuration at the carbon 5 as another structural parameter to consider. Among previously investigated barbiturates, chirality was centered either on the endocyclic carbon 5 (eg. mephobarbital, hexobarbital), on the exocyclic 5-substituent (pentobarbital, thiopental), or both (methohexital).46 In general, stereoisomers generated by either of these chiral centers displayed rather small differences in biological activities,9,47–54 although the precise assessment of this effect is difficult due to the different rates of the stereoisomer metabolism and differential binding by serum albumin.53 Hence, despite the plethora of available biological results, it is difficult to compare literature data on barbiturate potency and efficacy with those of the enantiomers of the compound 14 presented here. Barbiturates with a chiral center at C-5 were first investigated by Knabe, and their absolute configurations were determined by alkaline degradation and conversion into ethyltropic acid.46 These works have shown that dextrorotatory enantiomers of several N-methylbarbiturates including hexobarbital, mephobarbital and methylcyclobarbital had an S-configuration.46,55 In this regard, our compound 14 conforms to this pattern. To the best of our knowledge this report is the first to determine absolute configuration of a barbiturate by using x-ray crystallography, although a crystal structure of a racemic barbiturate has been reported previously.40

The early works on pharmacology of barbiturates with stereogenic carbon 5 showed that the change of substituents at this site from methyl to ethyl results in the reversal of enantiomer potency.9 Thus, for methylphenobarbital and hexobarbital, the S-(+)-isomers induced sleep and R-(−)-enantiomer was ineffective. In contrast, the R-(−)-isomers of 5-ethyl-5-cyclohexenyl barbiturate and mephobarbital were hypnotic agents, and the S-(+)-isomers had no activity.9,56 Further extension of the carbon-5 noncyclic substituent (i.e. from ethyl to propyl) did not change the relative enantiomer potency (R was still more potent than S), and the R-(−)-isomer was still an anesthetic, however the S-(+)-isomer was a convulsant.7 These differences indicate the importance of the substitution at 5-position for binding orientation and/or possibly for biological target selectivity. It is interesting that allyl-substituted barbiturate 14, behaves much like the 5-ethyl derivative, e.g. mephobarbital, since the R-enantiomer is a more potent isomer, and that at least from tadpole experiments there is no evidence of convulsive properties of the S-isomer. The unusually high potency of R-(−)-14 places it in the same league with propofol and R-(+)-etomidate, which have EC50 values of 2.2 and 2.3 μM, respectively).16,57 Compound 14 displays the highest enantioselectivity of any known barbiturate, with the eudismic ratio exceeding 10. Importantly, the 10-fold stereoselectivity is consistently observed for every parameter determined for this reagent so far: EC50 values for anesthetic activity, receptor potentiation, muscimol binding left-shifting, and inhibition of photoincorporation of [3H]R-(−)-14 by the nonradioactive stereoisomers.

Transgenic animal studies demonstrate that GABAA receptors mediate the major anesthetic actions of barbiturates.58 We investigated the stereoselective modulation of heterologously expressed GABAA receptors by compound 14 using both electrophysiology and ligand binding. Electrophysiological studies demonstrated that R-(−)-14 is a potent and efficacious modulator of GABA-induced receptor activity, and concentrations associated with general anesthesia produce large leftward shifts in GABA concentration-response curves (Figure 3). As observed with other potent general anesthetics, high concentrations of R-(−)-14 also directly activate GABAA receptors in the absence of orthosteric agonists (Figure 4). Muscimol binding to membranes of cells expressing GABAA receptors was also modulated by low micromolar concentrations of R-(−)-14 (Figure 5). The EC50 values characterizing R-(−)-14 potentiation of GABA-elicited receptor activity (2.1 μM) and muscimol binding (1.2 μM) are similar and close to the anesthetic half-effect concentration in tadpoles (3.7 μM, Figure 2). In comparison to R-(−)-14, the S-(+)-14 enantiomer displays lower potency (about 12-fold for binding assays) in GABAA receptor modulation assays, and electrophysiology also reveals diminished efficacy. Muscimol binding assays show similar efficacy for both enantiomers, and this likely reflects the fact that muscimol has the highest affinity for the desensitized state of the receptor, rather than the activated state monitored by electrophysiological experiments.

[3H]R-(−)-14 was found to be photoincorporated very efficiently into both subunits of the FLAG-α1β3 GABAA receptor with non-radioactive R-(−)-14 inhibiting photolabeling of both subunits with a concentration dependence (IC50 = 4 μM) that is close to the EC50 for anesthesia. The modification clearly targeted the barbiturate binding site, because pentobarbital inhibited [3H]R-(−)-14 photolabeling of both subunits with a concentration dependence (IC50 = 90 μM) close to that producing anesthesia in tadpoles (EC50 ~140 μM (Lee-Son et al. 1975; de Armendi et al. 1993).24,59 The similar pharmacological profiles for photolabeling in the β3 and α1 subunits suggests that this barbiturate binding site is not located in an intra-subunit bundle site as suggested for some agents.6,60 However, it will be necessary to identify the amino acids photolabeled by [3H]R-(−)-14 to determine at which of the possible alpha-beta interfaces the barbiturate binding site is located and at what level relative to the membrane.

Significantly, the efficiency of [3H]R-(−)-14 photoincorporation into the GABAAR appears quite high. The barbiturate–inhibitable photoincorporation of [3H]R-(−)-14 at 0.3 μM indicated photolabeling of ~9% and 3% of GABAAR β3 and α1 subunits, respectively, which is 10-fold higher than the 0.5% efficiency of α1β3 GABAAR subunit photolabeling seen for an aryldiazirine analog of etomidate.21 If the IC50 for inhibition of [3H]R-(−)-14 photolabeling by non-radioactive R-(−)-14 (4 μM) is a good estimate of the equilibrium dissociation constant for reversible binding, ~10% of GABAARs are occupied under our photolabeling conditions, and photolabeling efficiency at full occupancy may be close to 100%.

Conclusions

We have synthesized a photoactivatable diazirine analog of mephobarbital 14, separated its enantiomers by chiral chromatography, determined the configuration of the dextrorotatory isomer to be 5-S by x-ray crystallography, and performed preliminary pharmacological testing. We characterized general anesthesia in tadpoles, potentiation of GABA-induced α1β3γ2L receptor currents, increasing the α1β3γ2L receptor binding affinity of the GABAAR antagonist, muscimol, and photoincorporated the tritiated form of the reagent into the α1β3 GABAAR. In all examined aspects, R-(−)-14 proved an excellent probe, displaying high potency approaching those of propofol and etomidate, and very high efficiency of photoincorporation. Unlike other reported chiral barbiturates, this reagent is also highly stereoselective with enantiomer S-(+) having more than 10-fold lower potency in all regards. Reagent R-(−)-14 is expected to be a very useful probe for determining the binding site of barbiturates on Cys-loop receptors. The work to establish identities of the labeled amino acids residues in several receptor types is currently underway.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials

Dimethyl 2-allylmalonate and dimethyl 2-propargylmalonate were from Sigma-Aldrich. Anhydrous grade solvents were from Aldrich, and were not further dried or purified. [3H]R-14 (38 Ci/mmol) was synthesized by ViTrax Company (Placentia, CA) by tritiation of R-(−)-15 using the procedure described below. (±)-Pentobarbital was obtained from Sigma.

Analytical Chemistry

1H, 13C and 19F NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker Avance spectrometer at 400 MHz, 100 MHz and 376 MHz, respectively, unless otherwise noted. NMR chemicals shifts were referenced indirectly to TMS for 1H and 13C, and CFCl3 for 19F NMR. HRMS experiments were performed with Q-TOF-2TM (Micromass). Optical rotations were determined on Perkin-Elmer 241 polarimeter, in ethanol solutions at room temperature using a cell with 10 cm optical path. TLC was performed with Merck 60 F254 silica gel plates. Purity of the final compounds was assessed by HPLC analysis with a Synergy Hydro-RP column (4 μm, 4.60 × 150 mm) using methanol-water with 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid; the gradient applied was from 50% MeOH at the start to 100% MeOH over 18 min, followed by isocratic elution. Elution was monitored by UV at 280 nm. The analysis indicated purity greater than 96%. Chiral chromatography was performed using Daicell Chiralpack AD® column, 20×200 mm, eluted with isocratic 15% ethanol in hexane as an eluent at 6.5 mL/min flow rate.

Solubility, partition properties and pKa

The solubility of (±)-14 in 0.01 M Tris/HCl, pH 7.4 was determined by stirring excess compound in the buffer for 24 h, centrifuging at 10,000 g, and determining the concentration by reverse phase HPLC. To determine octanol/water partition coefficients of (±)-14, the compound was stirred in a two-phase mixture of octanol and water, aliquots were removed from the separated phases and applied to an HPLC Proto 300 C-18 5 mm reverse-phase column (Higgins Analytical, Inc., Mountain View, CA). The UV detector was set with an absorbance wavelength of 220 nm, the mobile phase consisted of 0.05% TFA in acetonitrile, with a flow rate of 1 mL/min, and the average fraction area in each phase was estimated.

The pKa value of the NH proton in (±)-14 was determined by pH titration in a dilute phosphate buffer and monitoring a change of the UV absorbance at 250 nm as a function of pH. In short, 25 μL of the stock solution of (±)-14 in methanol (16.0 mg/mL) was diluted with 0.1 M NaH2PO4 (25.0 mL). An aliquot of this solution having a starting pH of 4.63 was added with 1-100 μL aliquots of 2 M aqueous ammonia, and the pH and UV absorbance were determined. The titration curve for the pH range 4.5-9.3 (absorbance change from 0.058 to 0.345) was fitted to the Henderson-Hasselbach equation using the Kaleidagraph 4.1.0 software (Supporting Information, Figure 3). The pKa of 14 thus determined is 7.48±0.08.

Determination of the x-ray structure

A small colorless crystal, measuring roughly 5 × 10 × 20 micrometers, was mounted with oil on a nylon loop and cooled to 100 K in a liquid nitrogen stream. Data collection was carried out using a MAR 300 mm CCD detector with a wavelength near 0.82 Å, omega scans of 5°, and a crystal-to-detector distance of roughly 92 mm at the Advanced Photon Source, 21-ID-D. The space group was determined to be P21 (No. 4), with unit cell parameters of a=10.97, b=6.74, c=11.07 Å, β=106.95°, suggesting one molecule per asymmetric unit with composition C16H15N4O3F3. An Ewald sphere of data was collected, resulting in a total of 10,039 intensities. The intensities were scaled and averaged to 2857 reflections, with 2798 having intensities greater than 2σ(I); R(merge) = 0.141. Data processing was carried out using XDS software package.61

The structure was solved and refined using SHELX.62 All atoms were evident in an electron density map. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined with anisotropic Gaussian displacement parameters, and hydrogen atoms were restrained in idealized positions to their attached atoms. Final refinement yielded R(F) = 0.069 (all reflections), R(F) = 0.0682 (2σ cutoff), GOF = 1.084, with an extinction parameter of 0.30(4). When compared to the enantiomer, the favored absolute stereochemistry is reported as C5-S with a Flack parameter of - 0.1(11) (1.1 with the inverted structure), and a Hooft probability P2 = 0.995. PLATON software was used to make the ORTEP drawing.63

General Anesthetic Potency

Xenopus laevis tadpoles (Xenopus One, Dextor, Michigan) in the pre-limb-bud stage (1-2 cm in length) were housed in large glass tanks filled with Amquel+ (Kordon, div. of Novalek, Inc, Hayward, CA) treated tap water. Stock solutions of the test compounds were made in DMSO. With prior approval of the MGH Subcommittee on Research Animal Care, general anesthetic potency was assessed in the tadpoles as follows. Groups of 5 tadpoles were placed in foil-covered 100 mL beakers containing varying dilutions of the test compound in 2.5 mM Tris HCl at pH 7.4 under low levels of ambient light. The final concentration of DMSO did not exceed 0.01%. Every 5 minutes tadpoles were individually flipped using the hooked end of a fire-polished glass pipette until a stable response was reached (usually at 40 minutes). Anesthesia was defined as the point at which the tadpoles could be placed in the supine position, but failed to right themselves after 5 seconds (loss of righting reflex, LoRR). All animals were placed in a recovery beaker of Amquel+ treated tap water and monitored for recovery overnight. Each animal was assigned a score or either 0 (awake) or 1 (lost righting reflex), and the individual points were fit to a logistic equation by nonlinear least squares with the maximum and minimum asymptotes constrained to 1 and 0, respectively.

Electrophysiology of GABAA Receptors

With prior approval by the Massachusetts General Hospital Subcommittee on Research Animal Care, oocytes were obtained from adult, female Xenopus laevis (Xenopus One, Dextor, Michigan) and prepared using standard methods as described below. In vitro transcription from linearized cDNA templates and purification of subunit specific cRNAs was carried out using Ambion mMessage Machine RNA kits and spin columns. Oocytes were injected with ~100 ng total mRNA (α1, β2, γ2L) mixed at a ratio of 1:1:2 transcribed from human GABA receptor subunit cDNAs in pCDNA3.1.64 All two-electrode voltage clamp experiments were done at room temperature, with the oocyte transmembrane potential clamped at −50 mV and with continuous oocyte perfusion with ND96 (100 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 10 mM Hepes, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.8 mM MgCl2, pH 7.5) at ~2 mL/min. Barbiturate stock solutions were prepared in DMSO at a concentration of 100 mM for storage at −20°C. Compounds were further diluted in ND96 to achieve the desired concentration (the highest final DMSO concentration was 1%). All agents were applied for 15–25 s; oocytes were washed ~3 min between each application. Currents were amplified using an Oocyte Clamp OC-725C amplifier (Warner Instrument Corp), digitized using a Digidata 1322A (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA), and analyzed using Clampex/Clampfit 8.2 (Axon Instruments) and OriginPro 6.1 software.

Concentration response data were fit by nonlinear least squares regression to the Hill (logistic) equation (1) of the general form:

| (1) |

where X is the concentration of the activating ligand, IGABA,max is the maximally evoked current, EC50 is the concentration of X eliciting half of its maximal effect, and nH is the Hill coefficient of activation. Inhibition experiments were fit with logistic equations of the form:

| (2) |

Modulation of GABAA receptor [3H]muscimol binding

Modulation of the binding of the GABAA receptor agonist [3H]muscimol by the enantiomers of 14 was measured with isolated membrane homogenates of HEK293 cells expressing human α1β3γ2L GABAARs. R-(−)- and S-(+)-14 at increasing concentrations of 0, 0.01 (R-(−)-14 only), 0.1, 1, 3, 10, 30, 100, 150 and 300 μM (prepared from 100 mM stocks in DMSO) were incubated with α1β3γ2L membranes (0.15 mg membrane protein/mL) and 2 nM [3H]muscimol (35.6 Ci/mmol, Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA) at room temperature (21°C) for 60 min in the assay buffer containing 200 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA and 1x phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4, Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, New Jersey). Non-specific binding was measured in the presence of 1 mM GABA for selected concentrations only; controls showed non-specific binding to be independent of the concentration of compound 14 from 0 to 300 μM (data not shown). Reactions were quenched by placing samples on ice. They were filtered through 0.5% (m/v) polyethyleneimine-soaked Whatman GF/B glass fiber filters using a Millipore 1225 sampling manifold (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Filters were then each washed with 7 mL ice-cold assay buffer, dried under a lamp for over one hour, soaked in petroleum-based Liquiscint (National Diagnostics, Atlanta, CA) and analyzed on a Tri-Carb 1900 scintillation counter (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA). Modulation of [3H]muscimol binding was reported as percentage of the specifically bound [3H]muscimol over that without 14. Error bars represent propagated errors calculated from standard deviations over 8 or 12 independent filtrations from two or three independent incubations at each concentration. The modulation data from 0 to 150 μM were fit by nonlinear least squares regression to the Hill (logistic) equation (2) shown above using Igor 5 (Wavemetrics Inc., Lake Oswego, Oregon).

Photolabeling of expressed human α1β3 GABAAR with [3H]R-14

Human α1β3 GABAARs with a FLAG epitope at the N-terminus of the α1 subunit were expressed in a tetracycline-inducible, stably transfected HEK293S cell line as described.45 FLAG-α1β3 GABAARs were solubilized from membrane fractions with 2.5 mM n-dodecyl-β-d-maltopyranoside (DDM) and purified on an anti-FLAG M2 affinity resin as described.21 Receptors were eluted with 0.1 mM FLAG peptide in a purification buffer containing 11.5 mM cholate and 0.86 mM asolectin, frozen, and stored at −80°C until use. Membranes from 40-60 15-cm plates typically contained 5-10 nmol [3H]muscimol binding sites and yielded ~1 nmol purified receptor (30 – 50 nM binding sites) in 15-25 mL of elution buffer. For photolabeling, aliquots (4 pmol) of purified α1β3 GABAAR (150 μL, 23 nM muscimol binding sites final concentration) were equilibrated for 30 min at 4 °C with 1 mM GABA, 2 μCi [3H]R-(−)-14 (0.3 μM final concentration), and various concentrations of nonradioactive barbiturate in a total volume of 180 μL. Samples, in the wells of a 96-well plastic microtiter plate on ice, were irradiated for 30 min with a 365 nm Spectroline model EN-280L lamp at a distance of < 2 cm. Samples were then collected, mixed with 200 μL of sample buffer (9-parts 40% sucrose, 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 2% glycerol, 0.0125% bromophenol blue, and 0.3 M tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane, pH 6.8 and 1-part β-mercaptoethanol) for >15 min, and separated on a 1.5 mm thick,13 cm long, 6% acrylamide gel (0.24% Bis-acrylamide), with a 5 cm long, 4% acrylamide stacker. To accommodate the sample volume of 380 μL, the loading wells were 6 cm deep and 1 cm wide. After electrophoresis, gels were stained with Coomassie Blue stain and destained. The individual gel lanes were cut into 4 mm slices, and 3H in each gel slice was determined by liquid scintillation counting. Stock solutions of non-radioactive R-(−)-14 and S-(+)-14 were prepared at 87 mM in ethanol, with the concentrations determined from the absorbance at 350 nm (ε = 275 M−1cm−1). The final concentration of ethanol was <0.25% (v/v) in all photolabeled samples. To determine the concentration-dependence of inhibition by non-radioactive barbiturates of [3H]R-(−)-14 photoincorporation into each GABAAR subunit, the gel slice cpm were fit to the equation:

where Bx is the cpm at competitor concentration x. IC50 and bkg, but not B0 (the subunit gel slice cpm in the absence of inhibitor), were treated as adjustable parameters.

Trifluoroacetylation of iodobenzenes

A solution of butyllithium in hexanes (20 mL, 1.6 M, 1.6 eq.) was added into dry THF (150 mL) with stirring under argon, and the resulted solution was cooled to −78°C. The solution of 1,3- or 1,4-diodobenzene (6.48 g, 20 mmol) in THF (20 mL) was added dropwise. The resulting yellow solution was stirred at −78°C for 1 hour and treated with ethyl trifluoroacetate (7.2 mL, 60 mmol, 3 eq.). After warming up to room temperature, the reaction mixture was divided between water and hexane (100 mL each), the organic layer was washed with brine (50 mL), dried over MgSO4 and evaporated. In the case of compound 3, the unreacted p-diiodobenzene was partially removed by crystallization from hexane (2×10 mL). Chromatography on silica gel using hexane-dichloromethane (100:1 to 6:1 v/v) as eluent afforded pure compounds 2 and 3.

2,2,2-Trifluoro-1-(3-iodo-phenyl)-ethanone (m-7)

Yellow oil, yield 44%. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.41 (s, 1H), 8.10-8.02 (m, 2H), 7.32 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 179.3 (q, J = 35.7 Hz, CF3C=O), 144.3, 138.7 (q, J = 2.0 Hz), 131.6, 130.7, 129.1 (q, J = 2.3 Hz), 116.3 (q, J = 291.2 Hz, CF3), 94.5. 19F NMR (CDCl3): δ −71.5. LRMS (EI): 299.9 [M+], 230.9 [M-CF3]+, 202.9 [M-COCF3]+, 115.4 [M-CF3]2+, 104.0, 76.0, 50.0.

2,2,2-Trifluoro-1-(4-iodo-phenyl)-ethanone (p-8)

Light yellow solid, mp. 30-32°C, yield 40%. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.95 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.78 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): 180.1 (q, J = 35.3 Hz, O=CCF3), 138.6, 131.1 (q, J = 2.1 Hz), 129.2, 116.5 (q, J = 291.0 Hz), 104.6. 19F NMR (CDCl3): δ −71.5. LRMS (EI): 299.9 [M+], 230.9 [M-CF3]+, 202.9 [M-COCF3]+, 115.4 [M-CF3]2+, 104.0, 76.0, 50.0.

Conversion of trifluoroacetophenones m-7 and p-8 into diazirines m-9 and p-10, respectively

A mixture of trifluoroacetophenone (2.60 g, 8.67 mmol), hydroxylamine hydrochloride (1.00 g, 14.4 mmol, 1.7 eq.) and pyridine (1.0 mL, 13 mmol, 1.5 eq.) in methanol (5 mL) was heated under reflux for 2 hours, cooled and divided between ether (50 mL) and water (30 mL). The aqueous layer was additionally extracted with ether (20 mL). The combined organic layers were washed with 1 M HCl (2x5 mL), water and brine (10 mL each), dried over MgSO4 and concentrated under vacuum. The resulted crude oxime was added with dichloromethane (1 mL), cooled on an ice bath with stirring, the solution of p-toluenesulfonyl chloride (2.48 g, 13.0 mmol, 1.5 eq.) in pyridine (2.0 mL, 26 mmol, 3.0 eq.) was added dropwise, and the reaction mixture was left for 12 h at room temperature. After the completion of the reaction, the mixture was dissolved in dichloromethane (5 mL), cooled to −50°C and a solution of ammonia in methanol (7 M, 20 mL) was added dropwise with stirring. The resulted yellow suspension was allowed to warm up to room temperature and left with stirring for additional 48 hours. The excess of ammonia was evaporated under vacuum, and the reaction mixture was dissolved in a mixture of dichloromethane (10 mL), methanol (10 mL) and triethylamine (3.6 mL) and cooled to −20°C. A saturated solution of iodine in dichloromethane was added dropwise until the brown color of iodine persisted for at least 30 s. The reaction mixture was washed with a solution of sodium thiosulfate (5%, 1 mL), diluted with hexane (100 mL), washed with water (2×25 mL) and brine (20 mL), concentrated under vacuum and chromatographed on silica gel using hexanes as eluent (RF 0.7).

3-(3-Iodo-phenyl)-3-trifluoromethyl-3H-diazirine (m-9)

Yellow oil, yield 48%. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.79 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (s, 1H), 7.24 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 138.9, 135.3, 131.2, 130.4, 125.9, 121.8 (q, J = 274.7 Hz, CF3), 94.4 (C-I), 27.8 (q, J = 40.9 Hz, CN2). 19F NMR (CDCl3): δ −65.2. HRMS (ESI): Calcd. for [M-N2+H]+: 284.9383. Found: 284.9381.

3-(4-Iodo-phenyl)-3-trifluoromethyl-3H-diazirine (p-10)

Colorless low-melting solid, yield 70%. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.76 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, , 2H), 6.95 (dq, J = 8.6, 0.5 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): 138.0, 128.8, 128.1, 122.0 (q, J =274.6 Hz, CF3), 96.0 (C-I), 28.3 (q, J = 40.6 Hz, CN2). 19F NMR (CDCl3): δ −65.2. HRMS (ESI): Calcd. for [M-N2+H]+: 284.93825. Found: 284.9379.

Diaryliodonium salts

Into a vigorously stirred solution of aryl iodide (1.44 mmol) in TFA (7 mL) and CHCl3 (2 mL) maintained at 0°C was added Oxone® (0.65 g, 1.5 eq. [O]) in small portions over 5 minutes. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature until aryl iodide was exhausted as judged by TLC (Rf 0.6 in hexane). The reaction mixture was filtered, and the solution washed with chloroform-TFA (1:1, 2×10 mL). The pale-yellow filtrate was concentrated under vacuum, the residue suspended in dichloromethane-hexane (1:1, 50 mL), filtered, concentrated under vacuum, dissolved in the mixture of dichloromethane (10 mL) and TFA (0.5 mL) and cooled to −10°C. Anisole or mesitylene (4.5 mmol) was added at once, followed by stirring first at 0°C for 1 hour and one more hour at room temperature. The black-violet reaction mixture was concentrated under vacuum and the residue chromatographed on silica gel using first dichloromethane-hexane (1:1 v/v) as an eluent, followed by dichloromethane-hexane-methanol 25:25:1, 10:10:1 and 5:5:1 (salt elution); all the solvents contained 0.1% TFA. Concentration under vacuum and precipitation from dichloromethane-hexane 1:1 afforded a pure product as colorless crystals.

(4-Methoxyphenyl)phenyliodonium trifluoroacetate (2)

Yield 61%. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.92 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.88 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.54 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 6.91 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 3.83 (s, 3H, OMe). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 162.4, 137.0, 134.2, 131.6, 131.5, 117.6, 117.0, 105.0, 55.6. 19F NMR (CDCl3): δ −75.2 (CF3CO2−). HRMS (ESI): Calcd. for C13H11O3I [M-CF3CO2]+: 310.9927. Found: 310.9939.

Phenyl-(2,4,6-trimethylphenyl)iodonium trifluoroacetate (3).65

Yield 55%,. 19F NMR (CDCl3): δ −75.3 (CF3CO2−).

(4-Methoxyphenyl)-[3-(3-trifluoromethyl-3H-diazirin-3-yl)-phenyl]-iodonium trifluoroacetate (m-11)

Yield 58%. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.98 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 7.65 (s, 1H), 7.46 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (d, J = 8.0 Hz), 6.97 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 3.87 (s, 3H, OMe). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 163.6, 137.7, 135.0, 133.4, 132.4, 131.6, 130.2, 121.4 (q, J = 274.7 Hz, CF3), 118.4, 114.4, 101.1, 55.7, 27.9 (q, J = 41.5 Hz, CN2CF3). 19F NMR (CDCl3): δ −65.1 (3F, CN2CF3), −75.4 (3F, CF3CO2−). HRMS (ESI): Calcd. for [M-CF3CO2]+: 418.98627. Found: 418.9858.

(4-Methoxyphenyl)-[4-(3-trifluoromethyl-3H-diazirin-3-yl)-phenyl]-iodonium trifluoroacetate (p-12)

Yield 12%. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 7.95 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 2H), 7.87 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 7.17 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.91 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 2H), 3.84 (s, 3H, OMe). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 162.6, 161.8 (q, J = 34.7), 137.2, 134.4, 132.7, 129.1, 126.1 (q, J = 278.6, CF3CO2−, 121.6 (q, J = 275.0 Hz, CF3CO2−), 118.2, 117.6, 105.2, 55.6, 28.1 (q, J = 41.0 Hz, CN2CF3). 19F NMR (CDCl3): δ −64.9 (3F, CN2CF3), −75.2 (3F, CF3CO2−). HRMS (ESI): Calcd. for [M-CF3CO2]+: 418.98627. Found: 418.9855.

5-Alkyl-1-methylbarbiturates

The solution of dimethyl allylmalonate or dimethyl propargylmalonate (10 mmol) and N-methylurea (11 mmol) in methanol (5 mL) was treated with sodium methoxide (15 mmol, 3.2 ml of 25% by wt. in methanol) with stirring under argon and heated under reflux for 48 h. The reaction mixture was concentrated under vacuum, diluted with water (20 mL), and extracted with dichloromethane (3×10 mL). The combined organic phases were washed with brine, dried with MgSO4, concentrated and the residue was chromatographed on silica gel using hexane-ethyl acetate (3:1 to 2:1) as an eluent.

5-Allyl-1-methyl-pyrimidine-2,4,6-trione (4).66

Amorphous solid, yield 69%. 1H NMR (CDCl3): 9.07 (brs, 1H), 5.75 – 5.62 (m, 1H, =CH), 5.22 – 5.10 (m, 2H, =CH), 3.58 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, O=CCH), 3.28 (s, 3H, NCH3), 2.96 – 2.88 (m, 2H, =CH-CH2). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 168.6, 168.1, 150.6, 131.2, 120.3, 48.8, 34.2, 27.8. HRMS (ESI): Calcd. for [M+H]+: 183.07642. Found: 183.0766.

5-Allyl-1-methyl-5-phenyl-pyrimidine-2,4,6-trione (5)

Yield 81%. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 9.20 (brs, 1H, NH), 7.42 – 7.30 (m, 5H, Ph), 5.72 (ddt, J = 17.0, 10.2, 7.2 Hz, 1H, =CH), 5.28 (dq, J = 17.0, 0.8 Hz, 1H, =CH), 5.17 (dd, J = 10.2, 0.9 Hz, 1H, =CH), 3.34 (s, 3H, N-Me), 3.28 – 3.13 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 170.4, 169.7, 150.1, 137.0, 131.4, 129.3, 128.8, 126.2, 121.3, 61.1, 40.6, 28.3. Calcd. for [M-H]−: 257.0932. Found: 257.0942.

1-Methyl-5-(prop-2-ynyl)-pyrimidine-2,4,6-trione (13)

Colorless crystals, mp. 94-95°C, yield 52%. 1H NMR (CDCl3): 9.21 (brs, 1H), 3.60 (t, J = 4.5 Hz, 1H, O=C-CH), 3.33 (s, 3H, NCH3), 3.11-3.05 (m, 2H, CH2), 2.07 (t, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H, C≡CH). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 167.8, 167.2, 150.4, 77.9, 72.0, 47.7, 28.0, 19.7. HRMS (ESI): Calcd. for C8H9N2O3 [M+H]+: 181.0608. Found: 181.0599.

Arylation of 5-alkyl-1-methylbarbiturates

The solution of barbiturate 4 or 13 (1.5 mmol) in dry DMF (2 mL) was cooled on ice-salt bath under argon with stirring and NaH (60% in mineral oil, 48 mg, 1.2 mmol) was added portionwise over 5 min. The reaction mixture was warmed up to room temperature, stirred until gas evolution ceased completely, and diaryliodonium salt (1 mmol) was added at once. Stirring continued for 2 days at 40-45°C followed by evaporation in vacuum. The residual mass was chromatographed on silica gel using hexane-ethyl acetate 4:1 as an eluent to afford 5-alkyl-5-aryl-1-methylbarbiturate.

(±)-5-Allyl-1-methyl-5-[3-(3-trifluoromethyl-3H-diazirin-3-yl)-phenyl]-pyrimidine-2,4,6-trione (14)

Colorless crystals, yield 60% (90% from 15). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.67 (brs, 1H, NH), 7.44 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (dt, J = 8.0, ~1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.27 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (t, J ~ 2Hz), 5.69 (ddt, J = 17.1, 10.1, 7.2 Hz, 1H, =CH), 5.28 (dq, J = 17.1, 1.4 Hz, 1H, =CH), 5.20 (d, J = 10.1 Hz, 1H, =CH), 3.35 (s, 3H, NCH3), 3.16 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, CH2-CH=). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 169.9, 168.8, 149.4, 137.8, 130.6, 130.3, 129.8, 127.8, 127.1 (q, J = 1.3 Hz), 124.4 (q, J = 1.4 Hz), 121.9 (q, J = 274.6 Hz), 121.9, 60.7, 41.1, 28.4 (q, J = 40.7 Hz), 28.3. 19F NMR (CDCl3): δ −65.1. HRMS (ESI): Calcd. for [M-N2-H]− 337.0806. Found: 337.0797.

(±)-1-Methyl-5-prop-2-ynyl-5-[3-(3-trifluoromethyl-3H-diazirin-3-yl)-phenyl]-pyrimidine-2,4,6-trione (15)

Colorless oil, yield 51%. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 9.00 (brs, 1H, NH), 7.45 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.38 (dt, J = 8.2, ~1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.27 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.09 (t, J ~ 2 Hz), 3.40 (s, 3H, NCH3), 3.32-3.20 (m, J = 2.5 Hz, 2H, CH2-C≡CH,), 2.09 (t, J = 2.5 Hz, ≡CH). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 169.3, 168.2, 149.5, 136.4, 130.5, 130.0, 127.6, 127.5, 124.1, 121.9 (q, J = 275.0 Hz), 78.3, 72.0, 60.5, 28.6, 28.3 (q, J ~ 40.7 Hz), 26.9. 19F NMR (CDCl3): δ −65.1. HRMS (ESI): Calcd. for [M-H]−: 363.07105. Found: 363.0700.

Chiral separation and crystallization of (+)-14

Barbiturate 14 was separated into its enantiomers by chromatography on a preparative Daicell Chiralpack AD® column, 20×200 mm using 15% ethanol in hexane as an eluent at 6.5 mL/min flow rate. Under those conditions a baseline separation of enantiomers was achieved with retention times of 15.5 min for the (−)-enantiomer and 21.0 min for the (+)-enantiomer. The (+)-enantiomer was crystallized by slow evaporation of its 2:1 hexane-benzene solution.

Hydrogenation of barbiturates

Propargyl barbiturate 15 (12.0 mg, 0.033 mmol) was dissolved in methanol (1.2 mL) in a small septum vial and solid Rh(PPh3)3Cl (8.0 mg, 0.0086 mmol) was added at once. The reaction vial was purged with hydrogen and left stirred under H2 atmosphere from rubber balloon. The 1H NMR analysis of an aliquote of the reaction mixture taken after 5 minutes showed the completion of the reaction. The reaction mixture was filtered, concentrated under vacuum and chromatographed on silica gel using hexane-ethyl acetate (4:1) for elution. The progress of the hydrogenation could also be more conveniently monitored using silver-impregnated TLC plates. The plates were prepared by dipping regular plates in 1% CF3CO2Ag in methanol and drying at room temperature in the dark. Using hexane-ethyl acetate (4:1 v/v) for elution, the mobilities (Rf values) were as follows: 16 (Rf 0.3), 14 (Rf 0.2), 15 (Rf <0.05). These compounds were nonseparable on normal TLC plates. Compounds 14, 15 and 16 were also separated by HPLC using Phenomenex Luna 5 μm C18(2) 100 Å column, 3.00 × 150 mm at 1.0 mL/min flow rate. During the first 2 minutes isocratic 0.05 M TFA was used as an eluent; starting at 2 min the gradient of 0.05 M TFA/MeOH (0-100%) was used to reach 100% MeOH at 17 min, and elution was continued with isocratic MeOH. Using these conditions the retention times for compounds 14, 15 and 16 were 17.7, 17.2 and 18.0 min, respectively.

(±)-1-Methyl-5-propyl-5-[3-(3-trifluoromethyl-3H-diazirin-3-yl)-phenyl]-pyrimidine-2,4,6-trione (16)

Yield 60% (from 15). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 8.27 (brs, 1H, NH), 7.43 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.38 (dt, J = 8.0, ~1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.26 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.12 (t, J ~ 2Hz), 3.36 (s, 3H, NCH3), 2.45-2.31 (m, 2H), 1.43-1.21 (m, 2H), 1.00 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H, CH2CH3). 13C NMR (CDCl3): δ 170.4, 169.4, 149.5, 138.5, 130.2, 129.7, 127.6, 126.9, 124.2 (q, J ~ 1.0 Hz), 121.9 (q, J = 275.0 Hz), 60.8, 39.5, 28.4 (q, J = 40.7 Hz), 28.4, 19.1, 14.1. 19F NMR (CDCl3): δ −65.1. HRMS (ESI): Calcd. for [M-H]−: 367.10235. Found: 367.1017.

Supplementary Material

Scheme 1.

Scheme 3.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute for General Medicine to K.W.M. (GM 58448). Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U. S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Use of the LS-CAT Sector 21 was supported by the Michigan Economic Development Corporation and the Michigan Technology Tri-Corridor for the support of this research program (Grant 085P1000817). We thank Dr Alan Kozikowski of the Department of Medicinal Chemistry and Pharmacognosy of UIC for making available for us the HPLC equipment for chiral separations, and Dr Arsen Gaisin for technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- ACh

acetylcholine

- AMPA

α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid

- CNS

central nervous system

- DMSO

methyl sulfoxide

- EC50

concentration required for 50% of full effect

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- GABAAR

GABAA-type receptor

- IC50

concentration required for 50% of full inhibitory effect

- LoRR

loss of righting reflexes

- nACh

nicotinic acetylcholine

- nH

Hill coefficient

- SD

standard deviation

- TFD

trifluoromethyldiazirine

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Chiral chromatography of (±)-14, HPLC of the mixture after hydrogenation of compound 15, determination of pKa value of 14, and NMR data for all new synthesized compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- (1).Lopez-Munoz F, Ucha-Udabe R, Alamo C. The history of barbiturates a century after their clinical introduction. Neuropsych. Dis. Treat. 2005;1:329–343. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Doran WJ. In: Barbituric Acid Hypnotics in Medicinal Chemistry. Blicke FF, Cox RH, editors. vol. IV. Wiley and Sons; New York: 1959. pp. 1–334. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Mihic SJ, Harris RA. Hypnotic and Sedatives. In: Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollmann BC, editors. Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12th Ed. McGraw-Hill; 2011. Ch. 17. [Google Scholar]

- (4).Patel PM, Patel HH, Roth DM. General Anesthetics and Therapeutic Gases. In: Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollmann BC, editors. Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12th Ed. McGraw-Hill; 2011. Ch. 19. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Rudolph U, Antkowiak B. Molecular and neuronal substrates for general anesthetics. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;5:709–720. doi: 10.1038/nrn1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Krasowski MD, Harrison NL. General anesthetic actions on ligand-gated ion channels. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 1999;55:1278–1303. doi: 10.1007/s000180050371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Ticku MK, Rastogi SK, Thyagarajan R. Separate site(s) of action of optical isomers of 1-methyl-5-phenyl-5-propylbarbituric acid with opposite pharmacological activities at the GABA receptor complex. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1985;112:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(85)90232-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Andrews PR, Mark LG. Structural specificity of barbiturates and related drugs. Anesthesiology. 1982;57:314–320. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198210000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Büch HP, Schneider-Affeld F, Rummel W, Knabe J. Stereochemical dependence of pharmacological activity in a series of optically-active N-methylated barbiturates. Naunyn-Schmeiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 1973;277:191–198. doi: 10.1007/BF00501159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Miller KW, Sauter J-F, Braswell LM. A stereoselective pentobarbital binding site in cholinergic membranes from Torpedo californica. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 1982;105:659–666. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(82)91485-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Drexler B, Antkowiak B, Engin E, Rudolph U. Identification and characterization of anesthetic targets by mouse molecular genetics approaches. Can. J. Anaesth. 2011;58:178–190. doi: 10.1007/s12630-010-9414-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Zeller A, Arras M, Jurd R, Rudolph U. Identification of a molecular target mediating the general anesthetic actions of pentobarbital. Mol. Pharmacol. 2007;71:852–859. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.030049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Olsen RW, Li GD. GABA(A) receptors as molecular targets of general anesthetics: identification of binding sites provides clues to allosteric modulation. Can. J. Anaesth. 2011;58:206–215. doi: 10.1007/s12630-010-9429-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).McCracken ML, Borghese CM, Trudell JR, Harris RA. A transmembrane amino acid in the GABAA receptor β2 subunit critical for the actions of alcohols and anesthetics. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2010;335:600–606. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.170472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Husain SS, Nirthanan S, Ruesch D, Solt K, Cheng Q, Li GD, Arevalo E, Olsen RW, Raines DE, Forman SA, Cohen JB, Miller KW. Synthesis of trifluoromethylaryl diazirine and benzophenone derivatives of etomidate that are potent general anesthetics and effective photolabels for probing sites on ligand-gated ion channels. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:4818–4825. doi: 10.1021/jm051207b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Husain SS, Stewart D, Desai R, Hamouda AK, Li SG-D, Kelly E, Dostalova Z, Zhou X, Cotten JF, Raines DE, Olsen RW, Cohen JB, Forman SA, Miller KW. p-Trifluoromethyldiazirinyl-etomidate: A potent photoreactive general anesthetic derivative of etomidate that is selective for ligand-gated cationic ion channels. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:6432–6444. doi: 10.1021/jm100498u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Eckenhoff RG, Xi J, Shimaoka M, Bhattacharji A, Covarrubias M, Dailey WP. Azi-isoflurane, a Photolabel Analog of the Commonly Used Inhaled General Anesthetic Isoflurane. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2010;1:139–145. doi: 10.1021/cn900014m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Hall MA, Xi J, Lor C, Dai S, Pearce R, Dailey WP, Eckenhoff RG. m-Azipropofol (AziPm) a photoactive analogue of the intravenous general anesthetic propofol. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:5667–5675. doi: 10.1021/jm1004072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Stewart DS, Savechenkov PY, Dostalova Z, Chiara DC, Ge R, Raines DE, Cohen JB, Forman SA, Bruzik KS, Miller KW. p-(4-Azipentyl)propofol: A potent photoreactive general anesthetic derivative of propofol. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:8124–8135. doi: 10.1021/jm200943f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Li GD, Chiara DC, Sawyer GW, Husain SS, Olsen RW, Cohen JB. Identification of a GABAA receptor anesthetic binding site at subunit interfaces by photolabeling with an etomidate analog. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:11599–11605. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3467-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Chiara DC, Dostalova Z, Jayakar SS, Zhou X, Miller KW, Cohen JB. Mapping general anesthetic binding site(s) in human α1β3γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptors with [3H]TDBzl-etomidate, a photoreactive etomidate analogue. Biochemistry. 2012;51:836–847. doi: 10.1021/bi201772m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Li GD, Chiara DC, Cohen JB, Olsen RW. Neurosteroids allosterically modulate binding of the anesthetic etomidate to gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:11771–11775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C900016200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Li GD, Chiara DC, Cohen JB, Olsen RW. Numerous classes of general anesthetics inhibit etomidate binding to gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:8615–8620. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.074708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Lee-Son S, Waud BE, Waud DR. A comparison of the potencies of a series of barbiturates at the neuromuscular junction and on the central nervous system. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1975;195:251–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Alles GA, Ellis CH, Feigen GA, Redemann MA. Comparative central-depressant actions of some 5-phenyl-5-alkylbarbituric acids. J. Pharmacol. Exper. Ther. 1947;89:356–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Keach DT. The synthesis of 5-α-naphthyl-5-ethylbarbituric acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1933;55:3440–3442. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Mercier J. Molecular structure and anticonvulsant activity. Influence of phenobarbital, m-bromophenobarbital, and sodium bromide on audiogenic seizures in albino rats. C. R. Soc. Seances Soc. Biol. Fil. 1950;144:1174–1176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).DeLong DC, Doran WJ, Baker LA, Nelson JD. Preclinical studies with 5-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-5-ethyl-hexahydropyrimidine-2,4,6-trione. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1970;173:516–526. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Chen Q-H, Rao PNP, Knaus EE. Synthesis and biological evaluation of a novel class of rofecoxib analogues as dual inhibitors of cyclooxygenases (COXs) and lipoxygenases (LOXs) Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006;14:7898–7909. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Morgan ED. Synthesis of p-alkylphenylacetic acids. Tetrahedron. 1967;23:1735–1738. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Creary X. Reaction of organometallic reagents with ethyl trifluoroacetate and diethyl oxalate. Formation of trifluoromethyl ketones and alpha-keto esters via stable tetrahedral adducts. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:5026–5030. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Volonterio A, Zanda M. Three-component, one-pot sequential synthesis of N-aryl, N’-alkyl barbiturates. Org. Lett. 2007;9:841–844. doi: 10.1021/ol063074+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Oh CH, Kim JS, Jung HH. Highly efficient arylation of malonates with diaryliodonium salts. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:1338–1340. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Ansong O, Antoine MD, Nwokogu GC. Synthesis of difunctional triarylethanes with pendant ethynyl groups: Monomers for crosslinkable condensation polymers. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:2506–2510. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Brunner J, Semenza G. Selective labeling of the hydrophobic core of membranes with 3-(trifluoromethy1)-3-(m-[125I]iodophenyl)diazirin, a carbene-generating reagent. Biochemistry. 1981;20:7174–7182. doi: 10.1021/bi00528a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Zagulyaeva AA, Yusubov MS, Zhdankin VV. A general and convenient preparation of [bis(trifluoroacetoxy)iodo]perfluoroalkanes and [bis(trifluoroacetoxy)iodo]arenes by oxidation of organic iodides using oxone and trifluoroacetic acid. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:2119–2122. doi: 10.1021/jo902733f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Shah A, Pike VW, Widdowson DA. Synthesis of functionalized unsymmetrical diaryliodonium salts. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1997;1:2463–2465. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Bielawski M, Aili D, Olofsson B. Regiospecific one-pot synthesis of diaryliodonium tetrafluoroborates from arylboronic acids and aryl iodides. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:4602–4607. doi: 10.1021/jo8004974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Ghanem A, Al-Humaidi E. Chiral recognition ability and solvent versatility of bonded amylose tris(3,5-dimethylphenylcarbamate) chiral stationary phase: Enantioselective liquid chromatographic resolution of racemic N-alkylated barbiturates and thalidomide analogs. Chirality. 2007;19:477–484. doi: 10.1002/chir.20398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Bideau JP, Marly L, Housty J. Crystalline structure of 5-ethyl-1-methyl-5-phenylbarbituric acid. C. R. Seances Acad Sci. C. 1969;269:549–551. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Ambroise Y, Pillon F, Mioskowski C, Valleix A, Rousseau B. Synthesis and tritium labeling of new aromatic diazirine building blocks for photoaffinity labeling and cross-linking. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2001:3961–3964. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Hashimoto M, Kato Y, Hatanaka Y. Selective hydrogenation of alkene in (3-trifluoromethyl) phenyldiazirine photophor with Wilkinson’s catalyst for photoaffinity labeling. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2007;55:1540–1543. doi: 10.1248/cpb.55.1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Ni N, Sanghvi T, Yalkowsky SH. Independence of the product of solubility and distribution coefficient of pH. Pharm. Res. 2002;19:1862–1866. doi: 10.1023/a:1021449709716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Pistis M, Belelli D, Peters JA, Lambert JJ. The interaction of general anesthetics with recombinant GABAA and glycine receptors expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes: A comparative study. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;122:1707–1719. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Dostalova Z, Liu A, Zhou X, Farmer SL, Krenzel ES, Arevalo E, Desai R, Feinberg-Zadek PL, Davies PA, Yamodo IH, Forman SA, Miller KW. High-level expression and purification of Cys-loop ligand-gated ion channels in a tetracycline-inducible stable mammalian cell line: GABAA and serotonin receptors. Protein Sci. 2010;19:1728–1738. doi: 10.1002/pro.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Knabe J, Juninger H, Geismar W. Die absolute konfiguration einiger C-5-disubstitutierter 1-methylbarbitursäuren und ihrer Abbauprodukte. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1970;739:15–26. doi: 10.1002/jlac.19707390104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Arias HR, Mccardy EA, Gallagher MJ, Blanton MP. Interaction of barbiturate analogs with the Torpedo californica nicotinic acetylcholine receptor ion channel. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001;60:497–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Brunner H. Narcotic drug methohexital: Synthesis by enantioselective catalysis. Chirality. 2001;13:420–424. doi: 10.1002/chir.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Cordato DJ, Chebib M, Mather LE, Herkes GK, Johnston GAR. Stereoselective interaction of thiopentone enantiomers with the GABAA receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;128:77–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Tomlin SL, Jenkins A, Lieb WR, Franks NP. Preparation of barbiturate optical isomers and their effects on GABAA receptors. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:1714–1722. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199906000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Kamiya Y, Andoh T, Furuya R, Hattori S, Watanabe I, Sasaki T, Ito H, Okumura F. Comparison of the effects of convulsant and depressant barbiturate stereoisomers on AMPA-type glutamate receptors. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:1704–1713. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199906000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Büch H, Knabe J, Buzello W, Rummel W. Stereospecificity of anesthetic activity, distribution, inactivation and protein binding of the optical antipodes of two N-methylated barbiturates. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1970;175:709–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Büch HP, Krug R, Knabe J. Stereoselective binding of the enantiomers of four closely related N-methyl-barbiturates to human, bovine, and rat serum albumin. Arch. Pharm. (Weinheim) 1996;329:399–402. doi: 10.1002/ardp.19963290805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Richter JA, Holtman JR. Barbiturates: Their in vivo effects and potential biochemical mechanisms. Prog. Neurobiol. 1982;18:275–319. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(82)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Knabe J, Urbahn C. Die absolute konfiguration einiger disubstitutierter Cyanessigsäuren. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1971;750:21–27. [Google Scholar]

- (56).Christensen HD, Lee IS. Anesthetic potency and acute toxicity of optically active disubstituted barbituric acids, Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1973;26:495–503. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(73)90287-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Tonner PH, Miller KW. Cholinergic receptors and anesthesia. Anasthesiol. Intensivmed. Notfallmed. Schmerzther. 1992;27:109–114. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1000263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Jurd R, Arras M, Lambert S, Drexler B, Siegwart R, Crestani F, Zaugg M, Vogt KE, Ledermann B, Antkowiak B, Rudolph U. General anesthetic actions in vivo strongly attenuated by a point mutation in the GABA(A) receptor beta3 subunit. FASEB J. 2003;17:250–252. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0611fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).de Armendi AJ, Tonner PH, Bugge B, Miller KW. Barbiturate action is dependent on the conformational state of the acetylcholine receptor. Anesthesiology. 1993;79:1033–1041. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199311000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Nury HC, Van Renterghem C, Weng Y, Tran A, Baaden M, Dufresne V, Changeux JP, Sonner JM, Delarue M, Corringer PJ. X-ray structures of general anaesthetics bound to a pentameric ligand-gated ion channel. Nature. 2011;469:428–431. doi: 10.1038/nature09647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Kabsch W. XDS. Acta Cryst. 2010;D66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Sheldrick GM. A short history of SHELX. Acta Cryst. 2008;A64:112–122. doi: 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Spek AL. Structure validation in chemical crystallography. Acta Cryst. 2009;D65:148–155. doi: 10.1107/S090744490804362X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Stewart D, Desai R, Cheng Q, Liu A, Forman SA. Tryptophan mutations at azietomidate photo-incorporation sites on alpha1 or beta2 subunits enhance GABAA receptor gating and reduce etomidate modulation. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008;74:1687–1695. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.050500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Carroll MA, Wood RA. Arylation of anilines: Formation of diarylamines using diaryliodonium salts. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:11349–11354. [Google Scholar]

- (66).Ray R, Sharma JD, Limaye SN. Variations in the physico-chemical parameters of some N-methyl substituted barbiturate derivatives. Asian J. Chem. 2007;19:3382–3386. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.