Abstract

Background

The intensive physical and psychological stress of emergency medicine has evoked concerns about whether emergency physicians could work in the emergency department for their entire careers. Results of previous studies of the attrition rates of emergency physicians are conflicting, but the study samples and designs were limited.

Objective

To use National Health Insurance claims data to track the work status and work places of emergency physicians compared with other specialists. To examine the hypothesis that emergency physicians leave their specialty more frequently than other hospital-based specialists.

Methods

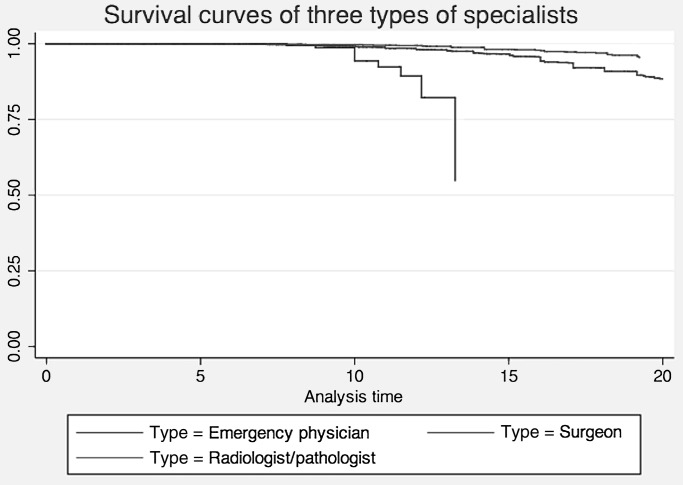

Three types of specialists who work in hospitals were enrolled: emergency physicians, surgeons and radiologists/pathologists. Every physician was followed up until they left the hospital, did not work anymore or were censored. A Kaplan–Meier curve was plotted to show the trend. A multivariate Cox regression model was then applied to evaluate the adjusted HRs of emergency physicians compared with other specialists.

Results

A total of 16 666 physicians (1584 emergency physicians, 12 103 surgeons and 2979 radiologists/pathologists) were identified between 1997 and 2010. For emergency physicians, the Kaplan–Meier curve showed a significantly decreased survival after 10 years. The log-rank test was statistically significant (p value <0.001). In the Cox regression model, after adjusting for age and sex, the HRs of emergency physicians compared with surgeons and radiologists/pathologists were 5.84 (95% CI 2.98 to 11.47) and 21.34 (95% CI 8.00 to 56.89), respectively.

Conclusion

Emergency physicians have a higher probability of leaving their specialties than surgeons and radiologists/pathologists, possibly owing to the high stress of emergency medicine. Further strategies should be planned to retain experienced emergency physicians in their specialties.

Keywords: Attrition, emergency physicians, burnout, abdomen, emergency department

Introduction

The intensive physical and psychological stress of emergency medicine has evoked concerns about whether emergency physicians could work in the emergency department (ED) for their entire careers.1–3 Compared with other specialists, emergency physicians have more stress factors. Work–family conflict, overnight shifts, general uncertainty and difficult patients often cause physical and emotional exhaustion among emergency physicians.1 4–9 Most previous studies using survey data found that the attrition rates of emergency physicians were varied,10–14 and no observational study has illustrated the working life of emergency physicians compared with other specialists.

In addition to estimation of the numbers of emergency physicians needed in one nation, it is also important to evaluate how long emergency physicians will be active in the clinical practice of emergency medicine. We aimed to use National Health Insurance (NHI) claims data to track the work status of emergency physicians compared with other specialists. The hypothesis is that emergency physicians will leave their specialty more frequently than other hospital-based specialists because of high stress and burnout.

Patients and methods

Data sources

The healthcare providers files of the NHI claims data were used in this study. Study subjects were physicians who were specialists certified by Department of Health in Taiwan between 1 January 1997 and 31 December 2010. We enrolled three types of specialists for comparison: emergency physicians, surgeons and radiologists/pathologists. Surgeons included neurosurgeons, general surgeons, plastic surgeons and orthopaedists. Radiologists/pathologists included radiologists, pathologists and nuclear medicine specialists. Physicians have to pass the board-certification examinations to become specialists.

Identification of attrition

In Taiwan, it is uncommon for emergency physicians, surgeons and radiologists/pathologists to practise in institutes other than hospitals. As a result, if a specialist changed his or her licence registration institute to an outpatient-based clinic, it would be recognised as ‘failure’. If the work status was labelled as ‘inactive’ in the NHI database, he or she would not perform any kind of medical-related practice and it would also be recognised as ‘failure’. If the physician kept working in the hospital during the study period, he would be labelled censored (non-event). Finally, if the physician was not registered in any healthcare institutions during the study period, he or she would also be labelled as ‘censored’. The follow-up period would be defined from the authorisation date of the specialty licence until the date of failure or censoring.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were compared with one-way analysis of variance, and categorical variables with χ2 test. 95% CI and p value were reported. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant. We first used log-rank test to examine whether different types of specialists had statistically different survival functions, and Kaplan–Meier curves were plotted to show the trend.

We further used a multivariate Cox regression model to adjust for age when the physician became the specialist and gender to calculate the HR of failure. All analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis Software for Windows, V.9.2 (SAS Institute Inc) and STATA V.11.2 (StataCorp).

Results

A total of 16 666 physicians (1584 emergency physicians, 12 103 surgeons and 2979 radiologists/pathologists) were identified between 1997 and 2010. The average follow-up period was 9.5 years. The mean age (SD) at the time when the specialty was certified was 36.7 (8.3) years. A total of 1395 (8.4%) physicians left the clinical practice of their specialties during the 14 years' observation period. The baseline characteristics of the three groups of specialists are summarised in table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of physicians with different specialties

| Characteristics | Emergency physicians (N=1584) | Surgeons (N=12 103) | Radiologists/pathologists (N=2979) | p Value |

| Men, n (%) | 1473 (93.0) | 11 347 (93.8) | 2308 (77.5) | <0.0001 |

| Age (years), n (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| <35 | 958 (60.5) | 6842 (56.5) | 1889 (63.4) | |

| 35–45 | 530 (33.5) | 3501 (28.9) | 774 (26.0) | |

| ≥45 | 96 (6.0) | 1760 (14.6) | 316 (10.6) | |

| Mean (SD) | 34.7 (5.5) | 37.2 (8.5) | 35.9 (8.4) | |

| Observed person-years | 54 51.3 | 124 483.1 | 28 580.3 | NA |

| Failure, n (%) | 10 (0.63) | 1298 (10.7) | 87 (2.9) | <0.0001* |

| Attrition rate (per 1000 person-year) | 1.83 | 10.42 | 3.04 | <0.0001 |

We first divided the cohort into three groups (emergency physicians, surgeons and radiologists/pathologists) and plotted the Kaplan–Meier curve to evaluate the survival function (figure 1). A sharp decrease of the slope in the emergency physicians group was noted after observation for 10 years, indicating higher attrition compared with other two groups after 10 years. The log-rank test was also statistically significant (p value <0.0001) (table 1).

Figure 1.

Survival curve of three kinds of specialists.

We than used the multivariate Cox regression model to evaluate the HRs of attrition from specialties compared with other two types of specialists. In comparison with surgeons, the adjusted HR of emergency physicians was 5.84 (95% CI 2.98 to 11.47) (table 2). In these two groups, male specialists seemed to remain in their specialties longer than female specialists (HR=0.43; 95% CI 0.22 to 0.83). As age increased, more specialists left their specialties. When specialists were older than 45 years old, the HR of leaving their specialties was 2.01 (95% CI 1.73 to 2.35) compared with those aged <35 years. In comparison with radiologists/pathologists, the adjusted HR of emergency physicians was 21.34 (95% CI 8.00 to 56.89). (table 3) Gender did not significantly increase attrition in this subgroup. In this group, specialists older than 45 years had a higher HR (1.87; 95% CI 1.05 to 3.35) than those aged <35 years. The statistical results are summarised in tables 2 and table 3.

Table 2.

Crude and adjusted HRs of attrition among emergency physicians and surgeons

| Factors | Crude HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p Value for adjusted HR |

| Surgeons | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Emergency physicians | 5.48 (2.80 to 10.72) | 5.84 (2.98 to 11.47) | <0.0001 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Male | 0.46 (0.24 to 0.89) | 0.43 (0.22 to 0.83) | 0.0119 |

| Age | |||

| <35 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.0 (reference) | |

| 35–45 | 1.21 (1.05 to 1.40) | 1.22 (1.06 to 1.40) | 0.0069 |

| ≥45 | 1.99 (1.70 to 2.31) | 2.01 (1.73 to 2.35) | <0.0001 |

Table 3.

Crude and adjusted HRs of attrition among emergency physicians and radiologists/pathologists

| Factors | Crude HR (95% CI) | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p Value for adjusted HR |

| Radiologists/pathologists | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Emergency physicians | 20.75 (7.81 to 55.15) | 21.34 (8.00 to 56.89) | <0.0001 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Male | 1.13 (0.57 to 2.24) | 0.94 (0.47 to 1.89) | 0.8646 |

| Age | |||

| <35 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| 35–45 | 1.58 (0.98 to 2.55) | 1.55 (0.96 to 2.50) | 0.0754 |

| ≥45 | 1.75 (0.99 to 3.10) | 1.87 (1.05 to 3.35) | 0.0339 |

Limitations

This NHI database has potential limitations. First, although this is the largest and most comprehensive public source for information about specialists in Taiwan, we cannot check the accuracy of these secondary data and some information is missing. Second, physicians might have different certified specialties and might register in the institutes using specialties other than our study interests. For example, an emergency physician might also be a certified cardiologist, and work in the hospital as a cardiologist and a part-time emergency physician. In our study cohort, he would be labelled as censored.

Many physicians work in the emergency department (ED) without this being their specialism, but in our database, we can capture only physicians with certified specialties. As a result, in the study we evaluated only the attrition of specialists instead of all physicians working in the ED. Finally, attrition was defined by primary type of practice and it is possible that physicians labelled as ‘failure’ work part time in emergency medicine clinical practice.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this observational study is the first to use a large cohort to follow up the working lives of emergency physicians. Based on the available information, only 0.63% of emergency physicians left emergency medicine clinical practice during the 14 years of observation. Cross-sectional examination of the data shows that the attrition rate is extremely low compared with reported rates.2 4 11–15 However, if individual observation periods are taken into account, we found that the ‘survival’ was significantly decreased after 10 years. In comparison with the other two kinds of specialists, the adjusted HRs were also significantly high. The findings demonstrate that the low annual attrition rate of emergency physicians may be too optimistic.

According to our findings, emergency physicians are about to leave this field when they are fully experienced. This would be a loss for the training programme of this specialty, and also for patients. Strategies to keep experienced emergency physicians in their ‘battlefields’—for example, by developing a less labour-intensive subspecialty (eg, disaster preparedness)—should be emphasised. In this way, emergency physicians might continue to work in hospitals passing on their experience when their physical ability declines.

In summary, our study found that despite the low annual attrition rate, in the long term there is a high probability that emergency physicians will leave their specialties compared with other specialists, possibly owing to the high stress of emergency medicine. Further strategies should be planned to retain experienced emergency physicians in their specialties.

Acknowledgments

This study is based in part on data from the National Health Insurance Research Database provided by the Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health, and managed by the National Health Research Institutes (registered number 99018 & 99321). The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of the Bureau of National Health Insurance, Department of Health, or National Health Research Institutes.

Footnotes

Contributors: Y-KL helped in data analysis, and wrote the paper. C-CL was involved in design, implementation, and data analysis. C-CC was involved in the data management. C-HW contributed to the writing of the paper. Y-CS was involved in the design, analysis, and contributed to the writing of the paper.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Leitzell JD. Emergency medicine: two points of view. An uncertain future. N Engl J Med 1981;304:477–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Klasner AE. Attrition rates of pediatric emergency medicine fellowship graduates. J Investig Med 2011;59:964–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ros SP, Scheper R. Career longevity in clinical pediatric emergency medicine. Pediatr Emerg Care 2009;25:487–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Estryn-Behar M, Doppia MA, Guetarni K, et al. Emergency physicians accumulate more stress factors than other physicians-results from the French SESMAT study. Emerg Med J 2011;28:397–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kuhn G, Goldberg R, Compton S. Tolerance for uncertainty, burnout, and satisfaction with the career of emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med 2009;54:106–13.e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Crook HD, Taylor DM, Pallant JF, et al. Workplace factors leading to planned reduction of clinical work among emergency physicians. Emerg Med Australas 2004;16:28–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. LeBlanc C, Heyworth J. Emergency physicians: “burned out” or “fired up”? CJEM 2007;9:121–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Spickard A, Jr, Gabbe SG, Christensen JF. Mid-career burnout in generalist and specialist physicians. JAMA 2002;288:1447–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cubrilo-Turek M, Urek R, Turek S. Burnout syndrome–assessment of a stressful job among intensive care staff. Coll Antropol 2006;30:131–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Counselman FL, Marco CA, Patrick VC, et al. A study of the workforce in emergency medicine: 2007. Am J Emerg Med 2009;27:691–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ginde AA, Sullivan AF, Camargo CA., Jr Attrition from emergency medicine clinical practice in the United States. Ann Emerg Med 2010;56:166–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goldberg R, Boss RW, Chan L, et al. Burnout and its correlates in emergency physicians: four years' experience with a wellness booth. Acad Emerg Med 1996;3:1156–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Doan-Wiggins L, Zun L, Cooper MA, et al. Practice satisfaction, occupational stress, and attrition of emergency physicians. Wellness Task Force, Illinois College of emergency physicians. Acad Emerg Med 1995;2:556–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hall KN, Wakeman MA, Levy RC, et al. Factors associated with career longevity in residency-trained emergency physicians. Ann Emerg Med 1992;21:291–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hall KN, Wakeman MA. Residency-trained emergency physicians: their demographics, practice evolution, and attrition from emergency medicine. J Emerg Med 1999;17:7–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]