ABSTRACT

In 2010, the Society of Behavioral Medicine heightened its priority to take an even more active role in influencing health-related public policy. Here we discuss the importance of behavioral medicine presence in public policy initiatives, review a brief history of SBM’s involvement in public policy, describe steps SBM is now taking to increase its involvement in health-related public policy, and finally, put forth a call to action for SBM members to increase their awareness of and become involved in public policy initiatives.

KEYWORDS: Public policy, Behavioral medicine

THE IMPORTANCE OF PUBLIC POLICY ADVOCACY FOR BEHAVIORAL MEDICINE RESEARCH

Advocacy can be defined as attempting to influence public policy through education, lobbying, or political pressure. As fewer dollars get spread across important federal, state, and local public health initiatives, the importance of advocating for the inclusion of evidence-based behavioral medicine research into programs, guidelines, and policies has never been greater. Preventable chronic conditions such as heart disease, cancer, obesity, HIV/AIDS, and diabetes account for 75% of the estimated $2 trillion annual health care costs in the US. Behavior is central to the prevention, development, and management of these diseases. Smoking, poor diet, sedentary lifestyle, alcohol intake, and risky sexual practices are directly related to the development of chronic diseases. Key behaviors in the prevention and management of chronic diseases include healthy diet, physical activity, medical regimen adherence, and stress management. Behavior is at the foundation of health, and therefore, behavior change is paramount in reducing the health care burden.

Evidence is mounting that behavioral interventions with individuals, families, organizations, and environments can prevent and/or delay disease, impact disease outcomes, improve disease management, and reduce health care costs. For example, brief smoking cessation counseling has been found to be cost-effective, and in concert with other cessation approaches, tobacco tax increases, clean indoor air laws, and counter-marketing campaigns have led to dramatic reductions in adult and youth smoking rates and concomitant reductions in premature deaths and billions of dollars in excess cost [1, 2]. In another example, programs promoting modest weight loss and physical activity have been shown to prevent diabetes in those at increased risk, substantially outperforming medication treatment [3, 4]. Ensuring that this type of evidence finds its way into funded initiatives, programs, and policies is critical to the health of the nation.

LONG-TERM IMPACT

The Society of Behavioral Medicine envisions directing evidence-based advocacy toward protecting and promoting the health of the public. Our 2,000 members—psychologists, health care providers, and public health, behavioral, and policy scientists—are experts on behavioral and environmental changes that can improve the public’s health and reduce health expenditures. To enhance the impact of our work on public health, we need to ensure our voices are heard at local, state, regional, and national levels on a wide range of issues.

MOVEMENT TOWARD ACTIVE POLICY ENGAGEMENT

In 2004, the SBM Health Policy Committee was developed with Debra Haire-Joshu as the inaugural chair. The primary charge was to develop policy briefs stemming from evidence-based behavioral medicine. The first policy brief, penned by Drs. Marian Fitzgibbon, Laura Hayman, and Debra Haire-Joshu, was on childhood obesity. The brief recommended an increase in funds for the implementation and evaluation of wellness policy initiatives relevant to the prevention of childhood obesity and that schools develop wellness policies that reflect evidence-based methods for promoting behavior change. Other policy briefs followed, on the topics of diabetes, health behavior change in primary care, and the role of behavior and environment in health.

In 2010, under the leadership of then SBM President Dr. Karen Emmons, the SBM Board of Directors approved the commitment of time and resources to move the Society toward a more active role in public policy. Due to the complexity of the policy landscape and sheer magnitude of issues relevant to behavioral science, Nelson, Mullins, Riley, and Scarborough—a Washington-based public affairs firm with expertise in advocacy—was contracted to review the SBM mission and then scan the federal policy environment to identify areas where SBM could contribute evidence to support or shape new legislation. This resulted in a public policy briefing that was presented during the October 2010 SBM Board Meeting. The goal was to identify a wide range of opportunities so that the board could select the top two or three that provided the best opportunity for both impact and member engagement. Table 1 includes areas that were identified by Nelson Mullins as potential opportunities for SBM.

Table 1.

Potential policy opportunities and examples of strategies for SBM

| Opportunity | Strategy examples |

|---|---|

| Pursuing annual appropriations process to secure federal investments in behavioral medicine research | Develop new and solidify existing working relationships with members of the Labor–HHS–Education Appropriations Subcommittee |

| Shaping health care reform | Focus attention on the science of translational behavioral medicine and its potential role in the implementation of health information technology |

| Weighing in on hot topics | Engage the White House Let’s Move! Initiative by sending a small delegation of SBM leaders to Capitol Hill with expertise in childhood obesity to discuss the Society’s role in the initiative. |

| Advancing and crafting legislation | Conduct an annual survey of legislation introduced, but not enacted, that could be supported by the Society |

| Leveraging constituent relationships to influence policy | Invite members of Congress to visit locations within his/her state to see how evidence-based behavioral interventions can improve health and reduce health care costs |

| Enhancing SBM’s national visibility | Build strong working relationships with key legislators and educate them about the benefits of behavioral medicine research and its translation into policy |

| Forging strategic alliances with like-minded organizations | Engage other organizations that would strengthen the impact of SBM’s message |

| Engaging with state-level leadership | Be aware of changes in state government and engage new governors and their staff when they are seeking input, advice, and counsel in health policy decisions |

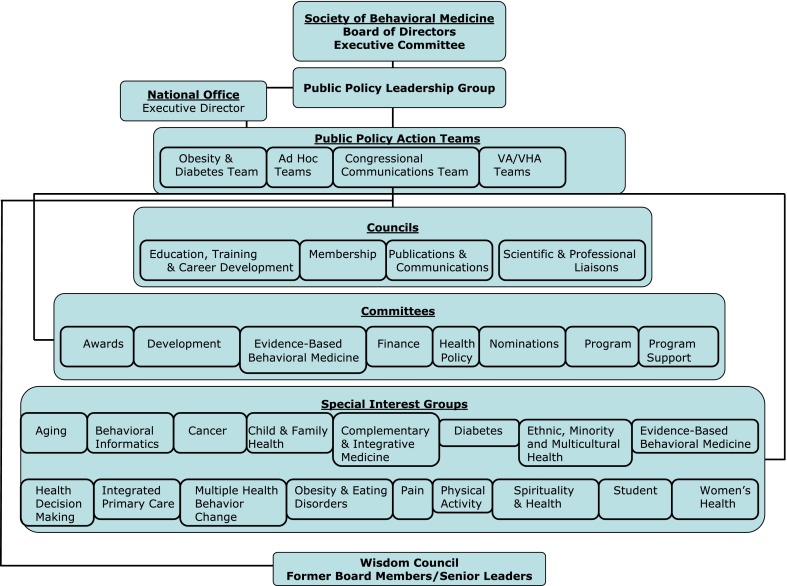

Following the Nelson Mullins briefing, the Board concluded, based on feasibility and importance, to focus on three primary areas: (1) shaping health care reform, (2) weighing in on hot topics, and (3) enhancing SBM’s national visibility related to policy-relevant science. Additions to the structure of SBM were initiated to make progress across these focus areas (See Fig. 1). First, the Public Policy Leadership Group was developed with the responsibility to (a) develop and advance public policy agenda, (b) facilitate the development of and review case statements requested or needed by congressional representatives, (c) identify and vet opportunities for endorsements, (d) identify and review members’ research to be shared with congressional representatives, and (e) engage special interest group (SIG) chairs and their members as appropriate for a given congressional need. Second, four Public Policy Action Teams were formed to respond to content-specific needs in advancing policy. The Obesity and Diabetes Action Team was developed to identify and respond to policy specifically relevant to obesity and diabetes. The VA/VHA Action Team was developed to build on the VHA’s substantial efforts to disseminate evidence-based behavioral medicine practices. The Ad Hoc Action Team refers to teams of SBM experts that will be formed to respond rapidly to emerging policy issues by providing behavioral medicine evidence in response to congressional requests. The Congressional Communications Action Team is a team composed of SBM leaders responsible for developing, implementing, and maintaining targeted communications with congressional leaders. Third, specific SBM committees and SIGs were identified as a network for rapid responses to the current requests from legislators. As additional public policy action areas arise, the intent is to engage all SIGs to enhance our ability to respond to policy needs in a timely fashion. Examples of recent activities relevant to each of the three primary areas are outlined below.

Fig 1.

SBM organizational structure

Shaping health care reform

Per the Public Policy Leadership Group, in February 2011, the Obesity and Diabetes Policy Action team drafted the SBM endorsement of the Healthy Lifestyles and Prevention America Act (S. 174) introduced by Senator Tom Harkin (D-Iowa). This bill is intended to reduce health care costs by increasing the nation’s focus on prevention, wellness, and health promotion. It addresses steps to promote healthier schools, workplaces, and communities and calls for expanded coverage of preventive services and for responsible marketing and consumer awareness pertaining to tobacco and unhealthy food.

Weighing in on hot topics

The Health Policy Committee developed a research brief on the importance of behavioral and psychosocial data elements for inclusion in the electronic health record (EHR). This brief is available on the SBM website and led to the development of an ambitious initiative to identify specific data elements and work toward consensus on items (http://www.sbm.org/UserFiles/file/SBMFINALmeasurebriefDec2010.pdf). A subgroup of the Health Policy Committee, the National Cancer Institute, and the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research organized a 3-phased approach to developing candidate data elements across 13 domains (see http://www.gem-beta.org/public/EHRInitiative.aspx?cat=4). In each phase of development, participants were asked to ensure the final data elements were brief, practical, and actionable. The first phase included having subject matter experts identify two to four potential measures for a given data element. The second phase included the use of the Grid-Enabled Measures Database to allow comments from the perspective of health care, research, patient advocacy groups, and the National Institutes of Health. This phase also included an objective rating of the measures. During the third phase, a town hall meeting was held on the NIH campus to generate recommendations for implementation. This activity resulted in ten constructs with specific measures for recommendation (anxiety and depression, eating patterns, physical activity, quality of life, risky drinking, sleep quality, stress, substance use, tobacco use, and demographics). The process of implementation of these data elements is ongoing. This initiative is also very relevant to shaping health care reform given that the HITECH Act and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act both emphasize the widespread and meaningful use of EHR.

Enhancing SBM’s national visibility in the policy arena

To increase SBM’s visibility with respect to national policy makers, 21 SBM representatives made visits to 22 legislative offices prior to the 2011 annual meeting. The goals were to familiarize congressional staffers and their legislators with SBM as well as position SBM as a resource for behavioral medicine research to advance public policies. Three specific talking points were used in each of the visits: (1) expression of support for a sustained federal investment in the National Institutes of Health and the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, (2) opposition to the repealing of the Prevention and Public Health Fund, and (3) recommendation to include mental health in the HITECH legislation. A number of lessons were learned during this activity. Perhaps the most important lesson was that legislators want to see evidence that supports our policy recommendations. For example:

Documentation of the benefits that could be achieved by implementing the Prevention and Public Health Fund would make our recommendations more compelling.

Legislators are most responsive to constituents from their own states.

While traditional research evidence is necessary, legislators are very interested in visiting local programs that are producing good health outcomes through prevention and behavioral science.

STILL MORE TO ACCOMPLISH: HOW CAN SBM MEMBERS GET INVOLVED?

At the 2010 SBM Annual Meeting and Scientific Sessions, we asked attendees for their opinions on how members could get involved in public policy. Some members expressed discomfort at functioning in an advocacy role personally, but a number were in strong support of SBM being on the front lines of emerging health-related policy. Being on the front lines requires identifying and understanding emerging policies as well as relationship building with legislators and other policy makers. SBM has responded and will take the lead in informing its members of emerging policies and recommending actions that members can take to make a difference.

While SBM has made significant headway into the policy world, much more is to be done, and significant impact will require the active engagement of our membership. As a scientist and/or practitioner, there are several ways in which SBM members can become involved in public policy and make a difference:

To ensure that members’ policy work represents board-approved statements, members should use the SBM talking points and policy briefs (http://www.sbm.org/about/public-policy/statements) as a resource when contacting legislators in their region. Making legislators aware of SBM and the wealth of knowledge it can bring to their legislative efforts will be extremely helpful to increasing the impact of behavioral medicine.

Pay attention to public policy initiatives that are relevant to your work. Follow the websites, Twitter, or other social networking feeds of initiatives, legislators, and/or programs to stay informed.

When policy issues relevant to behavioral medicine come to your attention or if you have success stories of evidence translation in your community, bring them to the attention of SBM (via astone@sbm.org). This will help SBM to respond as appropriate and bring the weight of the Society to bear on key issues. Also, your input will help us keep an up-to-date library of policy briefs, which is critical to rapid response.

Follow and disseminate the updates from SBM Public Policy Action Teams as they appear on the SBM website (http://www.sbm.org/about/public-policy).

Participate in the policy initiatives that are ongoing and relevant to behavioral medicine. Examples include Let’s Move, the Prevention Council, the National Diabetes Prevention Program, and the Electronic Health Records and Meaningful Use Initiative.

Educate students and trainees on why public policy is an important aspect of our work as well as how to identify and get involved in public policy that is relevant to their work.

CONCLUSION

Our strength as a Society lies in the rigorous and practical science that we produce. Given the wealth of evidence produced in the field of behavioral medicine, SBM is well positioned to have a significant impact on public policy. SBM has increased its efforts to become more actively engaged in influencing public policy and has made infrastructure modifications to better position the Society to quickly respond to emerging policy issues relevant to behavioral medicine. Through policy briefs and other products of the policy action groups and committees, SBM will continue to bring policy-related issues to the attention of individual members. As part of SBM’s efforts to position itself to have a more substantial impact on public policy, members are called to action to take steps to increase their awareness of health policies, engage with legislators, and help to disseminate the work of the behavioral medicine field in an effort to increase the visibility and impact of behavioral medicine research and practice on health policy at all levels. By working together in ways both large and small, we can make a difference more broadly in positively impacting the health and well-being of the human race.

Footnotes

Implications

Practice: SBM is positioned to respond to and help shape polices relating to health care practice given the wealth of evidence for behavioral medicine practices. Policies relating to greater coverage for and access to preventive services and behavioral health would greatly impact behavioral medicine practice.

Policy: Steps are outlined for how SBM and its members can influence health policy, thereby increasing the impact of the field on the health of individuals and communities.

Research: SBM is positioned to respond to and help shape policies relating to public funding of behavioral and population health research.

References

- 1.Thun MJ, Jemal A. How much of the decrease in cancer death rates in the United States is attributable to reductions in tobacco smoking? Tobacco Control. 2006;15(5):345–7. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.017749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Cigarette smoking among adults–United States, 2006. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2007;56(44):1157–1161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DPP Research Group Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hamalainen H, Ilanne-Parikka P, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344(18):1343–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]