Abstract

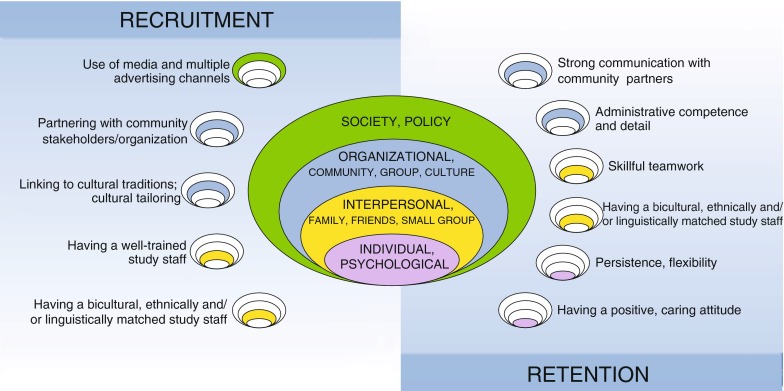

The purposes of this review are to (1) describe recruitment and retention strategies for physical activity interventions focusing on underserved populations and (2) identify successful strategies which show the most promise for “best practices” recommendations to guide future research. The method used was systematic review. Data on recruitment and retention strategies were abstracted and analyzed according to participant characteristics, types of strategies used, and effectiveness using an ecological framework. Thirty-eight studies were identified. Populations included African American (n = 25), Hispanic (n = 8), or Asian (n = 3) groups. Successful recruitment strategies consisted of partnering with respected community stakeholders and organizations, well-trained study staff ethnically, linguistically, and culturally matched to the population of interest, and use of multiple advertising channels. Successful retention strategies included efficient administrative tracking of participants, persistence, skillful teamwork, and demonstrating a positive, caring attitude towards participants. Promising recruitment and retention strategies correspond to all levels of ecological influence: individual, interpersonal, organizational, and societal.

Keywords: Recruitment, Retention, Underserved groups, Physical activity

BACKGROUND

With the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care for America (PPACA) Act in March 2010 [1], the affordability and accessibility of the US health care system is expanding to include millions of individuals and their families. Despite many politically contentious aspects about how PPACA will be implemented, provisions of the law strengthen the primary care system and community health centers, particularly those providing care to underserved groups, through its mandate to “…promote preventive health care at all ages and improve public health activities that help Americans live healthy lives…” [1]. PPACA also provides grants to states to provide Medicaid enrollees with incentives to participate in comprehensive health lifestyle programs and meet certain health behavior targets [2].

Recent data suggest that behavioral risk factors account for a greater portion of disparities than was previously thought [3]. The continuum of translational research, while initially conceived of as T0, (identification of problem and research opportunity), T1 (discovery or foundational research), and T2 (health application/efficacy research), has more recently grown to include T3 (moving evidence-based guidelines into health practice through implementation research) and T4 (evaluation of health outcomes on real-world, population health practice) [4, 5]. There is a critical need for data derived from T3 and T4 research, i.e., “real world” behavioral change research focused on underserved groups. One of the foremost challenges confronted by T3 and T4 research conducted with underserved populations is successful recruitment and retention of study participants.

Primary care settings offer great potential for successful recruitment and retention of underserved and underrepresented individuals and lower socioeconomic groups in health promotion research since primary care offers a trusted source of continuity across an individual’s lifespan and often serves entire families or generations. Safety net clinics and community health centers hold promise for reducing disparities because they provide the largest proportion of primary health care services to medically underserved and vulnerable populations [6]. Since primary care providers are on the front lines of managing medical complications related to inadequate physical activity [7], there is more than ever an urgent need to accelerate the translation of health promotion research into community-based and primary care settings.

It is well documented that underserved groups, defined herein as members of ethnic or racial minority groups or persons with low income, are less likely to have sufficient physical activity according to recommended guidelines [8, 9] and are more likely to suffer a greater burden of disease related to inadequate physical activity [10–12]. Historically, underserved groups have not been well represented in clinical trials to promote physical activity; however, this appears to be changing due to recent interventions more inclusive with respect to ethnic and socioeconomic diversity [13–16]. Involving communities and coalitions from the inception of research, mobilizing social networks, and targeting culturally appropriate messages and messengers all appear to be important characteristics of ethnically inclusive studies [17].

Despite recent progress made in physical activity interventions focused on underserved groups, many challenges related to implementation and sustainability remain [18]. Effective translation of research results to clinical practice depends on successful implementation and sustainability. In particular, recruitment and attrition difficulties are frequently cited challenges, and calls have been made for future research to focus on adequate recruitment and retention in order to foster sustainability and reach [15, 18–20]. Retention is often thought to reflect the percentage of participants that are retained for post-intervention assessments, not necessarily the actual intervention. Yet, for an intervention to be sustainable, maximizing participation in the intervention is the key. Strategies may differ for optimizing retention for a study assessment versus participation for an intervention’s sustainability. In this paper, we define successful recruitment as activities or strategies which yield the goal number of participants, ideally within a specified time frame. We considered successful retention to be strategies or activities which effectively kept participants in the study in sufficient numbers for planned analyses. Therefore, the goals of this paper are to: (1) describe the range of recruitment and retention strategies used in physical activity intervention trials focused on underserved populations in primary care and/or community settings and (2) identify successful strategies which show promise for “best practices” recommendations to guide future research. Because of conceptual and actual overlap between community-based studies that explicitly or implicitly incorporate a primary care medical setting, or vice versa, we chose to include both primary care and other community settings in this review. For example, community-based interventions may potentially affect discussions between targeted patients and their primary care physicians. Similarly, interventions focusing on primary care often involve referral to community resources. Given the recent health care reform in the US with the anticipated expansion of primary care and emphasis on preventive health care, a secondary goal was to describe recruitment and retention strategies for any primary care-based interventions identified.

METHODS

The primary author conducted a systematic review of the literature involving US-based trials to promote physical activity and which focused exclusively on an underserved population. Three individuals (the primary author and two medical librarians) developed the search strategy. The primary author and a medical librarian next independently searched the literature using the same key words and MeSH terms. The inclusion criteria for the literature review were that the study/paper (1) focused on recruitment and/or retention as the main topic (specifically, provided descriptions of the recruitment/retention methods, results, and discussion of their effectiveness, typically in three or more paragraphs throughout the paper), (2) occurred in a US population, (3) was published in an English-language journal, (4) had physical activity as an outcome measure, (5) had either a randomized or quasi-experimental design, and (6) focused exclusively or predominantly (>75%) on underserved participants. Studies could include adults and/or children. Studies that did not describe the pre-defined underserved groups in the abstract or text were excluded.

The following databases were searched for studies published between 1998 and 2010: Ovid/Medline, HealthSTAR, CINAHL, PsycINFO, PubMED, Cochrane, and HealthSTAR. Additionally, we completed citation and bibliographic searches of retrieved articles’ reference lists. We also contacted experts in the field of physical activity counseling interventions in an effort to obtain other relevant data. The primary author and the medical librarian conducted their searches independently; however, all search strategies were explicitly developed, executed, revised, saved, and compared together. The search terms (key words) are shown in Appendix 1.

The primary author reviewed titles and abstracts of all potentially relevant articles to determine if they met eligibility criteria for inclusion. For retrieved articles which met the inclusion criteria, the evaluation and abstraction of data for each study’s content were organized as follows: demographic information, recruitment and/or retention activities described, outcomes measured (e.g., whether recruitment and retention goals met and how measured), and results reported. We used previously published criteria for reporting recruitment and retention results [21]. Using these pre-defined criteria, data were extracted from each eligible article and organized into a table.

Since the literature tends to describe underserved populations as “hard-to-reach” with many types of barriers to recruitment and retention, we organized successful recruitment and retention strategies according to multiple levels of ecological influence [22]. The ecological framework integrates skills and choices of individuals with services and support they receive from family, community, organizations, culture, and physical and policy environments [23]. For health promotion research focused on underserved populations, literature has highlighted the importance of the various ecological levels. For example, individual factors, the role of family and community, organizations, and the built environment [24–27], all are associated with physical activity in underserved groups. Therefore, we chose an ecological approach as a framework to organize our findings about recruitment and retention for physical activity trials for underserved groups. By providing a broad unifying framework, we developed an empirically informed set of recommendations for “best practice” to guide recruitment and retention efforts.

RESULTS

General findings

The search was completed in June 2010. The primary search team retrieved a total of 996 titles using our key words listed above. Thirty-eight studies met the inclusion criteria. Reasons for exclusion included that the abstract was not topic related to physical activity (n = 490); was a descriptive paper, review, or essay (n = 322); was not a US or underserved population (n = 77); or had insufficient data on recruitment and/or retention (n = 69).

Intervention characteristics

Interventions most commonly were group-based classes; also included were promotion of walking [28–34], individual, home-based lifestyle physical activity (physical activity type not specified) [35, 36], and mixed/multiple types of activity [33, 37–39]. The majority of interventions were either neighborhood- or community-based (n = 11) or at community/cultural or recreation centers (n = 9). Other intervention venues consisted of churches [33, 40–43], primary care clinics [29, 38, 44, 45], home-based [30, 36], health clubs [46–48], and schools [35, 49–53]. Persons delivering the intervention varied; the interventionists’ training and background experience were inconsistently described.

Study population characteristics

Of the 38 studies, most (n = 25) focused on African American participants. Eight studies [29, 38, 48, 54–58] reported on Hispanic participants as all or part (50% or greater) of their study population of interest. Two studies purposively recruited a combination of Hispanic and African American participants [54, 56]. Three studies [39, 59, 60] focused on Asian populations, and two studies [37, 61, 62] had mixed/multiple ethnicities represented. The majority of interventions were for adults (n = 26), with fewer numbers of studies describing recruitment or retention strategies for children (n = 6) or family/parent–child dyads (n = 3). Most studies (n = 27) focused on urban populations, with smaller numbers of rural [29, 37, 44] or mixed [28, 55, 63] study environments. While all of the studies reported data on participants’ ethnicity and/or racial background fairly consistently, income and educational level of participants were reported in differing ways. In the majority of cases, specific data were reported for educational level (n = 25), income (n = 20), or income via indirect measures such as receipt of public assistance, neighborhood- or area-based socioeconomic data as proxies for participants’ educational or income levels (n = 8).

Types of recruitment and retention methods used

All studies reported multiple recruitment methods, and all studies described specific partnerships that were formed between the research team and community organizations. All studies emphasized the importance of having the research team members ethnically and/or linguistically matched to the study population as much as possible. Most studies stated that the recruitment strategies and materials were developed collaboratively with the partnering community organization and/or community advisory board; however, the level of detail describing how they accomplished this varied.

The most common recruitment methods consisted of targeted advertisements (newspapers, television, radio, posters), targeted mailings and/or telephone calls via use of phone lists from organizations, direct neighborhood canvassing (street outreach, visits or presentations to neighborhood businesses or organizations, or door-to-door recruitment to homes), and community or health fair presentations. There were several examples of innovative recruitment methods: social marketing via direct mailings from a magazine subscription list [46, 47], pay stub advertisements [61], development of a DVD or audio materials for study promotion to lower literacy groups, use of charismatic, respected community or youth leaders to directly appeal [28, 37], timing or linking recruitment to a cultural tradition [59], storytelling [28], and carefully planning culturally tailored, interactive pre-intervention/informational sessions [28]. For example, Banks-Wallace and colleagues developed an in-depth pre-intervention recruitment session for African American women which incorporated an adaptation of an African American folktale affirming the importance of culture and women working together to improve health. The story’s theme was woven into the description of study goals and procedures and allowed the researchers to complete their recruitment efficiently. For those studies that reported on it, social networking/word-of-mouth was a very effective means of recruitment [30, 46, 47, 54, 64].

Retention methods were described by 28 of the 38 studies; the other studies that did not report on retention explicitly stated that their purpose was to describe only recruitment issues. As with recruitment, all studies had multiple retention strategies; retention strategies were usually described in much less depth, however. The studies with the highest retention rates emphasized the importance of formative research and ongoing process evaluation that they conducted to specifically maintain or enhance retention via a carefully designed, well-developed, appealing intervention [7, 30, 37, 38, 43, 45, 49, 50, 53, 55, 56, 58, 65].

Retention techniques were described as administrative and/or interpersonal strategies. Common administrative retention strategies were to obtain multiple alternate contact numbers for participants [37, 53, 64], make multiple (10–20) contacts with participants during the study period [31, 38, 39, 45, 53, 54, 57], and maintain detailed databases and tracking registries for participants [29, 37, 59]. Providing financial or other incentives, transportation, or childcare were also commonly mentioned [29, 37–40, 42, 43, 45, 46, 48–50, 54–59, 63, 64].

Among the interpersonal strategies described for retention were for the study team to be persistent [54], have a positive, caring attitude towards participants [28, 29, 36, 38, 59], demonstrate cultural sensitivity and respect for participants’ life situations [28, 29, 36, 45, 49, 50, 56–60, 65, 66], meet regularly with community advisors and study staff for problem solving [34], and be flexible or accommodating to location and timing of study visits as much as possible [28, 29, 34, 36–38, 40, 59, 60].

Twenty-three of the 28 studies describing retention emphasized the importance of having bicultural, bilingual, and/or ethnically matched study team members as a key retention strategy [28, 29, 33–36, 38, 42, 43, 45–47, 49, 50, 54, 56–60, 63–66]. Beyond simply hiring bicultural, bilingual, or ethnically matched individuals to be on the study teams, studies also tended to have ethnically matched leadership influencing the questions framed and study design chosen [67]. Research leaders and staff also co-developed the specific retention strategies, the day-to-day monitoring of them, and problem-solving in culturally appropriate ways where applicable. For example, one study described how African American research team members affirmed potential participants’ concerns about research based on the participants’ prior experiences which had made them wary or mistrustful of the health care system. The research team’s affirmation helped them to retain participants [28]. Another study improved retention by timing the exercise intervention to occur after the Chinese New Year celebrations to accommodate family obligations and plans, and by using a well-qualified, charismatic Tai Chi instructor well-known to the local community [59]. All studies mentioned the importance of having study staff with strong interpersonal qualities and well trained in the protocol and procedures of the study.

Effectiveness of recruitment and retention methods used

Overall, 21 studies specified and met or exceeded their goal for recruiting their targeted number of participants. Seven of the 21 studies specified and met their goal for targeted timeline for recruitment. For retention, of the 28 studies that reported on retention, the retention rate ranged from 30% to 100%. Retention outcomes varied; they were typically defined as the percentage of those initially randomized and enrolled who completed post-intervention data collection. Duration of retention varied, ranging from 8 weeks to 5 years. The most frequent duration was 12 months (n = 13) with most studies (n = 31) 12 months or less. Table 1 summarizes the initial contacts, individuals eligible and screened, along with recruitment and retention rates (Table 2), for all studies with available information.

Table 1.

Description of identified studies (n = 38)

| Author | Sample | Design/Intervention | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Care Settings | |||

| Eakin et al. [88] | Latino adults; Primary care clinic in metropolitan Denver (n = 200) | Two-group RCT of dietary and physical activity intervention | 6 months |

| Martyn-Nemeth et al. [45] | Mexican-American adults in community-based clinic in Illinois (n = 19) | Single-group pre/post-design of a culturally adapted exercise program for diabetic adults | 6 months |

| Parra-Medina et al. [29] | Adult diabetics in rural, underserved counties in South Carolina (n = 189) | Three-group community translation trial of two weight management interventions compared to usual care | 12 months |

| Parra-Medina et al. [44] | African American women in community clinics in South Carolina | Two-group RCT to improve physical activity and dietary fat consumption | 12 months |

| Paschal et al. [42] | African American adults in urban low-income area in Wichita, KS (n = 134) | Single-group pre/post-design of a group-based health education and fitness program to improve blood pressure | 9 months |

| Community Settings | |||

| Banks-Wallace et al. [28] | African American women, community-based setting in mid-Missouri (n = 21) | Single-group pre/post-design to promote walking | 12 months |

| Beech et al. [66] | African American girls and their caregivers; YMCA and community center in Memphis, TN (n = 60) | Three-group RCT to prevent excess weight gain | 12 week |

| Chang [62] | African American and white mothers; the Special Supplemental Nutrition program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) in southern Michigan (n = 129) | Two-group RCT of a healthy eating, physical activity and stress reduction intervention | 10 weeks |

| Chen et al. [60] | Chinese American children and their mothers; Chinese language centers in San Francisco Bay area (n = 67) | Two-group RCT to promote healthy weight and lifestyles | 8 months |

| Chiang and Sun [39] | Chinese American adults; community centers in Massachusetts (n = 128) | Two-group pre/post-design of a walking program | 8 weeks |

| Escobar-Chaves [54] | African American and Latina women; Metropolitan Houston (n = 260) | Two-group pre/post-design of a group exercise and walking intervention | 8 weeks |

| Fitzgibbon et al. [35] | African American families in Chicago (n = 734 for both studies) | Design: (1) “Hip Hop for Health” was a two-group RCT aimed at dietary fat reduction and increased physical activity. (2) The Fat Reduction Intervention Trial in African Americans (FRITAA) was a two-group RCT to reduce fat intake. | 4 years (1) and 5 years (2) |

| Frierson et al. [61] | Adults; Metropolitan Houston (n = 1,245) | Two-group RCT of efficacy intervention to promote walking | 8 weeks |

| Gaston et al. [63] | African American women; 11 varied sites in Illinois, Washington, Florida, Maryland (n = 134) | Multiple-group (ten intervention groups and two comparison groups) pre/post-design of diet and exercise intervention | 12 months |

| Harralson et al. [48] | Latina adults; Latino-owned gym in Philadelphia neighborhood (n = 225) | Single-group pre/post-design of a combined educational/exercise intervention | 1 year |

| Hines-Martin et al. [34] | African American women; neighborhoods in Louisville KY (n = 51) | Single-group pre/post-design to promote physical activity | 6 months |

| Hovell et al. [57] | Latina adults; low-income community setting in North San Diego (n = 251) | Two-group RCT of group exercise intervention compared to safety educational intervention | 6 months |

| Keller et al. [31, 56, 57] | African American and Latina women; community settings in Texas (n = 47) | Two single groups, pre/post-designs of walking interventions | N/R |

| Merriam et al. [55] | Population: Caribbean-origin urban Latino adults; community and cultural centers in Lawrence, MA (n = 312) | Two-group RCT of usual care vs. intervention (locally adapted DPP) to promote lifestyle behavior change | 1 year |

| Pekmezi et al. [58] | Latinas with low income; university-based research setting in Providence, RI (n = 93) | Two-group RCT to promote physical activity | 6 months |

| Prohaska et al. [40, 89] | African American adults; church-based settings in Chicago (n = 123) | Single-group pre/post-design of a group-based exercise program | 4 months |

| Resnicow et al. [43] | African American girls ages 12–16; Atlanta metropolitan area churches (n = 137) | Two-group RCT of obesity intervention | 1 year |

| Resnicow et al. [68] | African American adolescents; public housing developments (n = 57) | Single-group pre/post-design of a physical activity/nutrition intervention | 6 months |

| Resnicow et al. [69, 79] | African American adults; African American churches in Atlanta metropolitan area (n = 1,056) | Three-group RCT with churches (n = 16) as unit of randomization;intervention was to increase fruit and vegetable consumption and physical activity | 1 year |

| Robinson et al. [65] | African American girls; after-school programs in Oakland and East Palo Alto, CA (n = 61) | Two-group RCT to reduce TV and weight gain | 12 weeks |

| Robinson et al. [90] | African American girls and their caregivers; after-school programs in Oakland, CA (n = 261) | Two-group RCT to reduce weight gain | 2 years |

| Rucker-Whitaker et al. [33] | African American women; churches and senior centers in Chicago (n = 46) | Single-group pre/post-structured self-management intervention | 6 weeks |

| Sharp et al. [64] | Adult Black women; university campus in Chicago (n = 213) | RCT of culturally adapted intervention followed by weight loss maintenance intervention | 6 months |

| Staffileno and Coke [36, 38] | African American women in Chicago (n = 23) | Randomized, parallel group, single-blind trial to promote individualized lifestyle activity | 8 weeks |

| Story et al. [50, 65] | African American girls 8–10 years old | Multi-center research program (GEMS) with centers in Houston, TX; Memphis, TN; Minneapolis, MN; and Palo Alto, CA | 12 weeks |

| Story et al. [49] | African American girls; after-school program in Minneapolis, MN (n = 54) | Two-group RCT to promote healthy eating and physical activity | 12 weeks |

| Taylor-Piliae et al. [59] | Adult Chinese immigrants; community center in San Francisco (n = 39) | Single-group pre/post-design to improve physical, psychosocial functioning | 12 weeks |

| Wilbur et al. [31] | African American women; neighborhoods in Chicago (n = 281) | Pre/post-design of a home-based walking intervention | 12 months |

| Wilbur J. et al [30] | African American women in Chicago (n = 281) | Two-group pre/post-design to promote home-based walking | 48 weeks |

| Wilson et al. [53] | 6th grade students; 24 middle schools in South Carolina (n = 1,422) | Group-randomized cohort design (three intervention and three comparison schools) to promote healthy eating and physical activity | 4 years |

| Yancey et al. [46] | Same as above | Same as above | Same as above |

| Yancey et al. [47, 65] | African American women; Black-owned community health club in Los Angeles | Two-group RCT of a diet/exercise intervention vs cancer screening/prevention education | 12 months |

RCT randomized controlled trial

Table 2.

Recruitment and retention results for the identified studies (n = 38)

| Author | Recruitment Methods | Recruitment results | Retention methods | Retention results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Care Settings | ||||

| Eakin et al. [88] | Bilingual staff | Initial contacts (n): 605 | Alternative contact numbers | Retention rate: 68.5% (n = 137) at 6 weeks, 81% (n = 162) at 6 months |

| Partnering with community health center | % screened: 57% (n = 345) | Making at least ten call attempts to locate participants, varying days and times | ||

| Use of electronic medical records | % eligible:75% (n = 258) | Maintenance of detailed database and tracking registry | Goal met: Yes | |

| Letters mailed to eligible patients from physicians | % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: 33% (n = 200) | Home visits | ||

| Follow-up phone calls | Length of time: 19 months | Flexible study design | ||

| Translation and cultural adaptation of intervention materials | Goal met: Yes | Regular staff meetings | ||

| Soliciting ongoing consultation | ||||

| Martyn-Nemeth et al. [45] | Soliciting input from community-based nurses | Initial contacts (n): N/R | Culturally appropriate music | Retention rate: 84% (n = 16) |

| Diabetic nurse educator familiar with the Hispanic community | % screened: N/R | Exercise sessions scheduled as clinic visits | Goal met: Yes | |

| Flyers posted in clinic with suggestion boxes | % eligible from those screening: N/R | Phone calls made for each missed session | ||

| Incentives | % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: n = 19 | Creative, periodic incentives (T-shirts, caps, socks, foot-care kits, water bottles, $10 gift cards, pedometers, copies of dance music and maracas) | ||

| Length of time: N/R | Bilingual facilitators | |||

| Goal met: Yes | Minimal written materials | |||

| Pedometers | ||||

| Social support promoted | ||||

| Location at clinic | ||||

| Parra-Medina et al. [29] | Partnering with statewide Primary Care Association | Initial contacts (n): 1,106 | Incentives (financial, transportation) | Retention rate: 81.5% at 12 months |

| Support from key stakeholders | % screened: 60.6% (n = 143) | Having a caring/concerned attitude | Goal met: N/R | |

| Involved staff in decisions about hiring | % eligible: 21.3% (n = 236) | Communication skills training for staff | ||

| Study staff on site to directly help health center | % enrolled from initial contacts: 17% (n = 189) | Flexibility and accommodations to schedules and life situations of participants | ||

| Staff trained extensively, with recertification every 6 months | Length of time: N/R | Detailed tracking systems | ||

| Potentially eligible participants via medical record review | Goal met: N/R | |||

| Prescreening telephone call | ||||

| Two screening, one randomization visit | ||||

| Parra-Medina et al [44] | Prior knowledge and experience of PI working in site settings | Initial contacts (n): 1,623 | N/A | N/A |

| Recruitment letters generated from scheduling system at health centers | % screened: 29% (n = 465) | |||

| Study brochures | % eligible from those screened: 75% (n = 350) | |||

| % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: 16% (n = 266) | ||||

| Length of time: 2 years | ||||

| Goal met: No | ||||

| Paschal et al. [42] | Media releases to news stations | Initial contacts (n): N/R | Program situated in primary healthcare facility in community | Retention rate: 70% (n = 94) at 6 months; 55% (n = 74) at 9 months |

| Radio announcements | % screened: N/R | Financial incentives | Goal met: No | |

| Outreach to African American churches | % eligible from those screening: N/R | African American staff | ||

| $150 stipend over 9 months | % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: n = 134 | Interactive group curriculum | ||

| Length of time: N/R | ||||

| Goal met: N/R | ||||

| Community Settings | ||||

| Banks-Wallace et al. [28] | African American staff | Initial contacts (n): 38 | N/A | N/A |

| Flyers in church bulletins and community | % screened: 65% (n = 25) | |||

| Word of mouth | % eligible: N/R | |||

| Referrals from practitioners | % enrolled from initial contacts: 55% (n = 21) | |||

| Radio talk show | Length of time: 3 months | |||

| Culturally tailored pre-intervention (informational) sessions | Goal: No | |||

| Beech et al. [66] | Public service announcements on African American radio stations | Initial contacts (n): 75 | Guided by formative research | Retention rate: 100% |

| PIs on live radio talk shows | % screened: 60 | Extensive, carefully designed intervention activities for each study arm. | Goal met: Yes | |

| Flyers at schools | % eligible from those screened: 80% | Varied, novel, interactive activities | ||

| % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: n = 60 | Well-trained interventionists, representative of community | |||

| Length of time: 2 months | ||||

| Goal met: Yes | ||||

| Chang MW [62] | Community partnerships with WIC centers | Initial contacts (n): 1,007 | Formative research | Retention rate: 40–51% per school |

| Peer advisory group formed | % screened: 33.9% (n = 342) | Flexibility of procedures | Goal met: No | |

| Formative research | % eligible from those screening: 56.7% (n = 194) | Alternate phone numbers | ||

| Recruiters received cultural sensitivity and communication skills training | % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: 12.8% (n = 129) | Toll-free study number | ||

| DVD to provide overview of study | Length of time: 2 months | Continuity of staff with participants | ||

| Goal met: Yes | Computerized tracking system | |||

| Reminder letters and thank-you notes after each interview | ||||

| Birthday and holiday cards | ||||

| Financial incentives at multiple points in study | ||||

| Chen et al. [60] | Partnership with Chinese language programs in the area | Initial contacts (n): 92; % screened: 78.2% (n = 72) | Interactive design | Retention rate: 85% (n = 57) |

| % eligible from those screening: 93% (n = 67) | Culturally appropriate information presented | Goal met: Yes | ||

| % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: 72.8 (n = 67) | Feasibility/accessibility addressed | |||

| Length of time: 16 months | ||||

| Goal met: Yes | ||||

| Chiang and Sun [39] | Snowball sampling | Initial contacts (n): N/R | Research staff had telephone contact weekly | Retention rate: 93% (n = 128) |

| Partnerships with a variety of community agencies: Chinese churches, a Chinese community center, and Chinese outpatient medical clinics | % screened: N/R | Incentives (pedometers) | Goal met: Yes | |

| % eligible from those screening: N/R | Attainable goal-setting emphasized | |||

| % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: n = 137 | ||||

| Length of time: 1 year | ||||

| Goal met: Yes | ||||

| Escobar-Chaves et al. [54] | Formative work with focus groups | Initial contacts (n): 656 | Financial compensation | Retention rate: 85.4 (n = 222)–98.8% (n = 257) |

| TV and radio ads | % screened: 65.4% (n = 386) | Convenience of meetings (both location and timing) | Goal met: Yes | |

| Presentations at health fairs and churches | % eligible: 89.9% (n = 590) | Transportation provided | ||

| Advertisements in community newspapers | % enrolled from initial contacts: 39.6% (n = 260) | Advance planning with logistics/appointments | ||

| Bilingual/bicultural posters | Length of time: 27 months | Frequent (as many as 12) contact/phone calls | ||

| Advisory board | Goal met: Yes | Well-trained study staff | ||

| Research staff matched by language and ethnicity | ||||

| Fitzgibbon et al. [35] | (1) “Hip Hop for Health”: recruited through well-known after-school program; follow-up mailings and phone calls. Study site was established at housing complex also. | Initial contacts (n): 5,180 for FRITAA +1,350 (HHH) | N/A | N/A |

| (2) FRITAA: community public awareness campaigns; house-to-house canvassing; telephone recruitment | % screened: N/R | |||

| % eligible: N/R | ||||

| % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: 8.1% (n = 420 for FRITAA) and 23.2% (n = 314 for HHH) | ||||

| Length of time : 3 years for Hip Hop to Health, 18 month for FRITAA | ||||

| Goal met: Yes | ||||

| Frierson et al. [61] | News ads, some of which were targeted to diverse racial/ethnic groups | Initial contacts (n): 1,245 (260 black) | N/A | N/A |

| Health fairs | % screened: 493 (92 black) | |||

| Radio ads | % eligible: 256 (36 black) | |||

| Pay stub ads | n enrolled from initial contacts: 249 (34 black) | |||

| Worksite ads | Length of time: N/R | |||

| Goal met: No | ||||

| Gaston et al. [63] | Buy-in from directors of programs in recruitment settings | Initial contacts (n): N/R | African American female midlife group leaders | Retention rate: 79% (n = 106) at 10 weeks, 31% (n = 42) of initial enrollees at 6 months, 39% (n = 52) at 12 months |

| African American female co-leaders of the project | % screened: N/R | Participants given $10 per session to defray transportation or childcare costs | Goal met: N/R | |

| % eligible from those screening: N/R | ||||

| % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: 134 | ||||

| Length of time: N/R | ||||

| Goal met: N/R | ||||

| Harralson et al. [48] | Partnerships with existing programs at women’s wellness center of an urban community-based organization serving low-income women | Initial contacts (n): N/R | Financial incentive( $40 for pre- and post-test surveys) | Retention rate: 52% (n = 118) |

| % screened: N/R | Weekly drawing for $10 gift certificate | Goal met for retention: No | ||

| % eligible from those screening: N/R | $100 gift certificate drawing based on max attendance | |||

| % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: n = 225 | Childcare and tokens for transportation provided | |||

| Length of time: 20 months | ||||

| Goal met: Yes | ||||

| Hines-Martin et al. [34] | Formative research and detailed strategic planning | Initial contacts (n): 244 | Maintaining relationships with community and center | Retention rate: 81.7% at 6 months |

| African American staff and/or longstanding community members | % screened: N/R | Respect and flexibility for participants | Goal met: Yes | |

| Use of flyers, word-of-mouth, community meetings, health fairs | % eligible: 72.1% (n = 176) | Childcare provided | ||

| % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts:42.6%(n = 104) | Integrating social and educational activities into protocol | |||

| Length of time: less than 3 months | PI very visible | |||

| Goal met: Yes | Team present in community events | |||

| Hovell et al. [57] | Presentations to local schools,at retail outlets, in waiting rooms, and door-to-door | Initial contacts (n): N/R | Continuous, vigorous outreach | Retention rate: 91% at 6 and 12 months |

| Small group slide presentation of study given in Spanish | % screened: N/R | Exercise buddies/compadres | Goal met: Yes | |

| % eligible from those screening: N/R | Phone calls from Spanish-speaking staff for each missed class | |||

| % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: 151 | Home visits for more than three missed classes | |||

| Length of time: N/R | Different staff involved until pt either returned or officially dropped out | |||

| Goal met: N/R | Used post-intervention monthly mailings and holiday, birthday cards | |||

| Multiple incentives built in for attendance | ||||

| Provision of childcare and tutoring program | ||||

| Keller et al. [31, 56, 57] | N/A | Initial contacts (n): N/A | Formative work (focus groups) to inform intervention design with specific strategies to address safety | Retention rate: 48%, 55% |

| % screened: N/A | Convenience, flexibility | Goal met for retention: No | ||

| % eligible from those screening: N/A | ||||

| % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: N/A | Childcare provided | |||

| Length of time: N/A | Promoters and lay health advisors for support | |||

| Goal met: N/A | ||||

| Merriam et al. [55] | Patient lists from health center registry | Initial contacts (n): 2,638 | Not specifically discussed | Retention rate: 93% (n = 290) at 1 year |

| Mailing invitations from health center | % screened: 36% (n = 949) | Transportation provided as needed | Goal met: Yes | |

| Telephone recruitment calls | % eligible: 41.2% (n = 391) | |||

| Public service announcements | % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: 11.8% (n = 312) | |||

| Guest spots on local Spanish TV, advertisements in bilingual news | Length of time: 34 months | |||

| Fliers in Senior Center newsletter | Goal met: No | |||

| Pekmezi et al. [58] | Partnerships with community-based organizations | Initial contacts (n): 388 | Formative research process to culturally adapt intervention | Retention rate: 87% (n = 81) |

| Advertisements in Spanish-language newspapers and radio stations | % screened: 81.1% (n = 315) | Proactive strategies to explicitly address barriers developing “brand” (Seamos Activos), logo | Goal met: Yes | |

| % eligible from those screening: 29% (n = 93) | ||||

| % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: 23.9% (n = 93) | ||||

| Length of time: 6 months | ||||

| Goal met: Yes | ||||

| Prohaska et al. [40, 89] | N/A | Initial contacts (n): N/R | Church setting familiar to participants | Retention rate: 57% (n = 70) |

| % screened: N/R | Existing social structure and support | Goal met: Yes | ||

| % eligible from those screening: N/R | Offering free program | |||

| % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: n = 123 | Flexibility in program for all fitness levels | |||

| Length of time: 1 month | ||||

| Goal met: Yes | ||||

| Resnicow et al. [68] | Public housing developments | Initial contacts (n): N/R | Interactive intervention sessions | Retention rate: 98% (n = 56 completed post-assessments); 55% (n = 31) completed final six sessions |

| Presentations | % screened: N/R | Use of multiple incentives healthy meals provided | Goal met: Yes/No | |

| Posters and flyers | % eligible from those screening: N/R | Camaraderie/social support | ||

| In-person recruiters | % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: n = 57; | |||

| Home-based consent process and baseline data collection | Length of time: N/R | |||

| Goal met: Yes | ||||

| Resnicow et al. [69, 79] | Extensive formative research | Initial contacts (n): N/R | Extensive formative research guided the development of the intervention materials; multiple focus groups | Retention rate: 86% (n = 906) at 1 year |

| % screened: N/R | Goal met: Yes | |||

| % eligible from those screening: N/R | ||||

| % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: 1,056 | ||||

| Length of time: N/R | ||||

| Goal met: Yes | ||||

| Resnicow et al. [43] | Church liaisons hired as hourly employee | Initial contacts (n): N/R | Extensive formative research to develop themes and content areas for intervention. | Retention rate: 84% (n = 123) at 6 months, 73% (n = 107) at 12 months |

| Churches received $500 incentive for 15 girls enrolled, plus additional $200 if 20 girls enrolled | % screened: N/R | Goal met: N/R | ||

| % eligible from those screening: N/R | ||||

| % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: n = 137 | ||||

| Length of time: N/R | ||||

| Goal met: N/R | ||||

| Robinson et al. [65] | Presentations at community centers and after-school programs | Initial contacts (n): N/R | Extensive formative research | Retention rate: 98.4% |

| Youth leaders | % screened: N/R | Frequent classes at multiple sites | Goal met: Yes | |

| Posting fliers | % eligible from those screening: N/R | Serving healthy snacks | ||

| % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: 61 | Homework period | |||

| Length of time: 10 weeks | Dance classes varied | |||

| Goal met: Yes | Home visits | |||

| African American female role model | ||||

| African and African American cultural themes and values | ||||

| TV time managers | ||||

| Newsletters | ||||

| Holistic concept of health | ||||

| Control group planning | ||||

| Robinson et al. [90] | Developed from formative research | Initial contacts (n): N/R | N/A | N/A |

| Targeted low-income neighborhoods around schools | % screened: n = 543 | |||

| Presentations, flyers distributed to girls at schools and parents at after-school programs, schools, churches, neighborhood events | % eligible from those screened: 58% (n = 316) | |||

| All assessments performed in girls’ homes | % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: 83% (n = 261) | |||

| Eligibility criteria kept as liberal as possible | Length of time: 16 months | |||

| Goal met: Yes | ||||

| Rucker-Whitaker et al. [33] | Opportunistic recruitment from senior center and two churches | Initial contacts (n): N/R | African American peer leaders/role models | Retention rate: 100% |

| % screened: N/R | Goal met: Yes | |||

| % eligible from those screening: N/R % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: n = 46 | ||||

| Length of time: N/R | ||||

| Goal met: N/R | ||||

| Sharp et al. [64] | Directly handing out flyers/brochures in public spaces | Initial contacts (n): N/R | African American instructors | Retention rate: N/R |

| Door-to-door canvassing of area within 2-mile radius of site | % screened: 690 | Varied range of aerobic activities offered | Goal met: N/R | |

| Word-of-mouth from church and community leaders | % eligible: 39% (n = 266) | Supplemental optional social activities | ||

| Mass email at local university | % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: 31% (n = 213) | Pedometers provided | ||

| Length of time: 2 years | ||||

| Goal met: Yes | ||||

| Staffileno and Coke [36, 38] | Blood pressure screenings | Initial contacts (n): N/R | Identifying and overcoming participants’ barriers | Retention: 95.8% (n = 23) |

| Physician referrals | % screened: 136 | Developing strong relationships | Goal met: Yes | |

| Posting flyers and brochures | % eligible: 26% (n = 35) | Social support | ||

| Work-site presentations | % enrolled from initial contacts: n = 24 | Demonstrating respect | ||

| Networking, word-of-mouth | Length of time: 19 months | Flexibility in scheduling study visits | ||

| Advertisements via newspaper, radio | Goal met: No | Training of research staff with aforementioned skills | ||

| Internet sources. | ||||

| Story et al. [49] | N/A ( see other Story et al. references in this table [50, 65]) | Initial contacts (n): N/R | Well-trained African American staff | Retention rate: 98% (n = 53) |

| % screened: N/R | Fun activities/programming | Goal met: Yes | ||

| % eligible from those screening: N/R | Cultural tailoring based on formative research | |||

| % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: n = 54 | Interactive, varied classes | |||

| Length of time: N/R | Incentives built in | |||

| Goal met: Yes | Healthy snacks provided | |||

| Transportation provided | ||||

| Location convenient (school) | ||||

| Weekly family packets | ||||

| Family night events | ||||

| Use of active control group (self-esteem) | ||||

| Story et al. [50, 65] | Radio announcements | Initial contacts (n): N/R | N/A | Retention rate: N/A |

| Direct appeal to religious and community leaders | % screened: N/R | Goal met: N/A | ||

| Flyers at schools and community centers | % eligible from those screening: N/R | |||

| Internet | % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: n = 210 | |||

| Information sessions | Length of time: N/R | |||

| Direct appeal by PI | Goal met: Yes | |||

| Presentations at community events | ||||

| Letters to students and parents | ||||

| Taylor-Piliae et al. [59] | Partnership with a community-based agency | Initial contacts (n): 60 | Tracking attendance | Retention rate: 97.4% (n = 38) |

| Use of multimedia (radio, flyers, news ads, brochures left in a variety of locations) approach in Chinese and English | % screened: 86.6% (n = 52) | Convenient location | Goal met: Yes | |

| Bilingual communication | % eligible: 75% (n = 39) | Bicultural/bilingual study personnel | ||

| Demonstrating cultural sensitivity | % enrolled from initial contacts: 65% (n = 39) | Personal encouragement | ||

| Length of time: 3 weeks | Qualified/charismatic Tai Chi instructor | |||

| Goal met: Yes | Respect for Chinese cultural beliefs, norms and values | |||

| Incentives | ||||

| Maintaining good communication among staff | ||||

| Wilbur et al [30] | African American, female staff | Initial contacts (n): 696 | N/A | N/A |

| Formative work to develop recruitment materials | % screened: n = 67.3% (n = 469) | |||

| Community advisory board | % eligible: 40.4% (n = 281) | |||

| community presentations, health fairs | % enrolled from initial contacts: 40.4% (n = 281) | |||

| Broad community dissemination of print materials | Length of time: 28 months | |||

| Email announcement to worksites | Goal met: Yes | |||

| Childcare made available | ||||

| Promptly returned calls and made as many as 10 attempts to respond to callers | ||||

| Wilbur et al. [31] | Occurred via two federally qualified health centers serving low- and middle-income populations; see other Wilbur et al. paper in this table [30] | Initial contacts (n): Not reported in this paper (see other Wilbur reference in this table) | Multiple attempts made to contact participants | Retention rate: 82–97% at 24 weeks, 30–44% at 48 weeks |

| % screened: N/R | Goal met: N/R | |||

| % eligible from those screening: N/R | ||||

| % enrolled (n) from initial contacts: 281 | ||||

| Length of time: N/R | ||||

| Goal met: N/R | ||||

| Wilson et al. [53] | Parent orientations at school events to get parental consent | Initial contacts (n): 2,500–3,000 | Detailed tracking database | Retention rate: 40–51% per school |

| Pep rallies | % screened: 52.1–62.5% (n = 1,563) | Phone scripts with follow-up actions | Goal met: No | |

| Homeroom visits | eligible from those screening: 90.9% (n = 1,422) | Updated contact information | ||

| % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: 47.4–56.8% (n = 1,422) | ||||

| Length of time: 4 years | ||||

| Goal met: Yes | ||||

| Yancey et al. [46] | N/A | Initial contacts (n): 2009; % screened: 44.4% (n = 893) | Convenient site/centrally located | Retention rate: 70–72% |

| % eligible from those screened: 95% (n = 845); % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: 20% (n = 393) | Black-owned fitness facility | Goal met for retention: N/R | ||

| Length of time: 18 months | Free 1-year membership provided | |||

| Goal met: Yes | ||||

| Yancey et al. [47, 65] | African American leadership (PI) and study staff. | Initial contacts (n): 2009 | N/A | N/A |

| Recruitment materials containing ethnically relevant Afrocentric messages, themes, and format | % screened: 44.4% (n = 893) | |||

| Mass media including radio public service announcements, flyers in community sites, direct mail | % eligible from those screened: 95% (n = 845) | |||

| Social networking | % enrolled (and n) from initial contacts: See following reference; Length of time: 18 months | |||

| Goal met: Yes | ||||

N/A not applicable (not focus of paper), N/R not reported or unknown

Studies reported on why recruitment or retention was effective—or ineffective—using many different methodologies. Some studies used qualitative techniques such as participant or researcher observations [28, 45, 59, 63], focus groups [43, 48, 68, 69], and participant interviews or surveys. Others used quantitative techniques such as analyzing tracking and enrollment registries according to recruitment strategy [46, 47, 49]. Others described mixed method approaches such as a process evaluation [53]. The studies with the highest retention rates had extensive formative research and prior experience with their community (or communities) of interest, used community input to develop the intervention carefully, had leadership and/or team members who were ethnically or linguistically matched to participants, and emphasized respect, caring, and frequent communication with participants. In some studies, it was difficult to discern whether goals for recruitment and retention had been set or met because this information was not always reported. Closely related constructs to retention—such as measures of participation or engagement [70] (i.e., attendance rates at intervention sessions)—were reported less frequently. When reported these rates tended to be much lower than overall study retention; that is, participants had lower rates of attending all intervention sessions but did complete follow-up assessments.

Primary care-based studies

Of the five primary care-based studies [29, 38, 42, 44, 45], recruitment and retention goals were variably described and not consistently met. Study samples ranged from 15 to 266 participants. Recruitment strategies mostly made use of patient lists from electronic health records or other patient registries, with letters and follow-up phone calls to potentially eligible participants. Most studies described the importance of soliciting input from staff, tailoring activities to suit the clinical environment, and having bilingual, well-trained research staff. Three studies reported retention rates, which ranged from 55% to 84%. Most studies reported that reasons for attrition were related to poor health, transportation difficulties, childcare, or other family obligations.

Figure 1 shows the most successful recruitment and retention strategies, framed within an ecological perspective, to develop “best practices” recommendations for future research in the field. As seen from Fig. 1, successful strategies encompassed all levels of ecological influence. Having a bicultural, ethnically, and/or linguistically matched research team was important for both recruitment and retention. Other important attributes were for the research team to have strong interpersonal skills, respect, and cultural sensitivity towards participants. Administrative flexibility and organization, persistence, and allowing for adequate time, staffing, and resources were important. Using a variety of methods, tracking progress closely, and consulting with team members and community advisors were also very important.

Fig 1.

Ecological levels of influence with corresponding successful recruitment and retention strategies

DISCUSSION

This review adds to the existing literature by (1) exploring the relationship between strategies and outcomes for recruitment and retention and (2) guiding the development of “best practices” recommendation for future research in the field, framed within an ecological perspective (Fig. 1). Many of the successful strategies highlighted in Fig. 1 echo the themes expressed in qualitative work from diverse cultures as well as the perspectives of research recruiters themselves [71–76]. Different methodologies (qualitative, quantitative, mixed) may be used to translate and evaluate recruitment and retention strategies in different settings.

A major theme evident from this review is the critical importance of extensive formative research to develop recruitment and retention strategies that take into account the unique study site, context, or population-specific attributes. Formative work is optimized by community engagement and empowerment in all phases of the study [77, 78]. Several studies with high retention rates also tended to describe significant time and effort to design the intervention (and control group) to be as appealing as possible, culturally tailoring, and making the intervention highly interactive [65, 66, 79]. Therefore, in order to translate research findings into other clinical and community settings, consideration of contextual factors is essential. Depending on the context, one or more levels of ecological influence may be particularly salient.

We found an extremely limited and uneven evidence base related to successful recruitment and retention in primary care settings. However, other recent interventions in primary care or general medicine settings have been effective [7, 80–83], though challenging to implement [84], so this area may also be worthy of further study.

There were gaps in our existing knowledge base apparent from this review. Effectiveness of recruitment or retention was defined differently in the studies we reviewed. As a result, it was challenging to analyze recruitment and retention consistently across studies due to variability in reported versus unreported or unknown data. There is limited information from the participants’ perspectives on what was most valuable or important to them for facilitating recruitment or retention, though there are reports of facilitators and barriers to physical activity in culturally diverse groups [72, 76, 85]. Also, the small number of family and rural interventions suggests that more research is needed in these areas. Since results were inconsistently analyzed by education or income level, we do not know the extent to which recruitment or retention methods may have differentially affected individuals with low-income or low-educational attainment. Innovative approaches and use of social networking were described in a limited fashion overall, though we did discover some intriguing, creative strategies worthy of further study.

Overall, the studies reported moderately or extremely high recruitment and retention rates, raising the question of to what extent publication bias limits our understanding of less effective methods and outcomes. The results of this review highlight the complexity and difficulty of defining and achieving “sufficient” recruitment and retention. Goals (and reporting standards) for recruitment and retention should be discussed not just in terms of numbers of participants recruited and retained, but also time and staff development required [86].

There are limitations that should be kept in mind when interpreting the results from this review. First, the data were abstracted by one reviewer which may have introduced reviewer bias. Another limitation is that the “gray literature”—i.e., other programmatic evaluations, internet-based sources, or other work not published in the bibliographic databases described herein—was not searched, which may have limited the yield of relevant findings. The selection criteria for this review excluded non-US-based studies, which may have provided additional information as well. Finally, due to the challenging nature of recruitment and retention for underserved populations, this review may have been subject to publication bias, thus limiting the generalizability of these findings.

CONCLUSION

In order to successfully recruit and retain individuals from underserved groups into physical activity intervention trials, promising strategies correspond to all levels of ecological influence. Successful recruitment and retention is grounded in having a well-trained, bicultural, and/or ethnically and linguistically matched research team, cultural tailoring of the intervention, administrative competence, strong community partnerships, and interpersonal skills.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere thanks to Margaret Chretien for devoting her time and effort with the bibliographic searches, and Pamela White for her support with the search strategy as well. Special thanks to Adjuah VanKeken for her work in retrieving and indexing articles and to Vi Luong for her support in designing Fig. 1. We also appreciate the effort of Dawn Case and Bonnie Schwartzbauer for their technical editing and formatting assistance. Finally, thank you to all of the authors whose work is represented in Table 1 for their support and replies to verify information for this paper. Funding for this project was supported by the National Cancer Institute. (Identifying information on grant details and PI is omitted in this manuscript version per journal submission).

APPENDIX 1

Search terms used for review.

Physical activity, patient selection, clinical trial, research, motor activity, intervention, exercise, locomotion, program, rural/rural areas, patient education, feasibility, poverty/poverty areas, sports, pilot, African American, Asian American, recruitment, Hispanic, ethnic groups, retention, minority groups, educational status, walking, physical fitness, resistance training, prevention, ambulatory care, primary health care, bicycling, internal medicine, pedometer, accelerometer, community health centers, recreation, senior center, physicians/family, and socioeconomic factors

Footnotes

Implications

Practice: Effectiveness of recruitment and retention should be more systematically and explicitly reported to inform sustainability, reach, and clinical relevance of programs.

Policy: Research funding for interventions with underserved groups should support the personnel time, training and development required for meaningful formative research and recruitment and retention strategies.

Research: Given the importance of having ethnically- and linguistically-matched study leadership and staff, there should be resources directed to expand the research workforce at all levels to be more representative of underserved groups.

References

- 1.United States Government. Summary of Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care Act. http://docshousegov/energycommerce/SUMMARYpdf 2010. Accessed on June 20, 2010.

- 2.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. (2010) Health reform source: implementation timeline. Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. Available at: URL: http://healthreform.kff.org/timeline.aspx.

- 3.Stringhini S, Sabia S, Shipley M, et al. Association of socioeconomic position with health behaviors and mortality. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303(12):1159–1166. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute of Translational Health Sciences. (2010) About translational research. ITHS. Available at: URL: http://www.iths.org/about/translational.

- 5.Khoury MJ, Gwinn M, Yoon PW, Dowling N, Moore CA, Bradley L. The continuum of translation research in genomic medicine: how can we accelerate the appropriate integration of human genome discoveries into health care and disease prevention? Genetics in Medicine. 2007;9(10):665–674. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31815699d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Health Resources and Services Administration Bureau of Primary Health Care. (2008) The health center program: reporting highlights. Ref Type: Online Source

- 7.Sherman BJ, Gilliland G, Speckman JL, Freund KM. The effect of a primary care exercise intervention for rural women. Preventive Medicine. 2007;44(3):198–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control Prevalence of regular physical activity among adults—United States, 2001–2005. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2007;56(46):1209–1212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Baltimore: Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor WC, Baranowski T, Young DR. Physical activity interventions in low-income, ethnic minority, and populations with disability. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;15(4):334–343. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crespo CJ, Smit E, Andersen RE, Carter-Pokras O, Ainsworth BE. Race/ethnicity, social class and their relation to physical inactivity during leisure time: results from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2000;18(1):46–53. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(99)00105-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitt-Glover MC, Crespo CJ, Joe J. Recommendations for advancing opportunities to increase physical activity in racial/ethnic minority communities. Preventive Medicine. 2009;49(4):292–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitt-Glover MC, Kumanyika SK. Systematic review of interventions to increase physical activity and physical fitness in African-Americans. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2009;23(6):S33–S56. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.070924101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teufel-Shone NI, Fitzgerald C, Teufel-Shone L, Gamber M. Systematic review of physical activity interventions implemented with American Indian and Alaska Native populations in the United States and Canada. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2009;23(6):S8–S32. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.07053151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pekmezi D, Jennings E. Interventions to promote physical activity among African Americans. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 2009;3:173–184. doi: 10.1177/1559827608331167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banks-Wallace J, Conn V. Interventions to promote physical activity among African American women. Public Health Nursing. 2002;19(5):321–335. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2002.19502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yancey AK, Kumanyika SK, Ponce NA, McCarthy WM, Fielding JE. Population-based interventions engaging communities of color in healthy eating and active living: a review. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2004;1:1–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumanyika SK, Yancey AK. Physical activity and health equity: evolving the science. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2009;23(6):S4–S7. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.23.6.S4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eakin EG, Glasgow RE, Riley KM. Review of primary care-based physical activity intervention studies: effectiveness and implications for practice and future research. The Journal of Family Practice. 2000;49(2):158–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green LW, Ottoson JM, Carcia C, Hiatt RA. Diffusion theory and knowledge dissemination, utilization, and integration in public health. Annual Review of Public Health. 2009;30:151–174. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P. Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008;148:295–309. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-4-200802190-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stokols D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion. 1996;10(4):282–298. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher EB, Brownson CA, O'Toole ML, Shetty G, Anwuri VV, Glasgow RE. Ecological approaches to self-management: the case of diabetes. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(9):1523–1535. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Booth KM, Pinkston MM, Poston WS. Obesity and the built environment. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2005;105(5 Suppl 1):S110–S117. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2005.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cleland V, Ball K, Hume C, Timperio A, King AC, Crawford D. Individual, social and environmental correlates of physical activity among women living in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighbourhoods. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70(12):2011–2018. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.King AC, Satariano WA, Marti J, Zhu W. Multilevel modeling of walking behavior: advances in understanding the interactions of people, place, and time. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2008;40(7 Suppl):S584–S593. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31817c66b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King AC, Castro C, Wilcox S, Eyler AA, Sallis JF, Brownson RC. Personal and environmental factors associated with physical inactivity among different racial–ethnic groups of US middle-aged and older-aged women. Health Psychology. 2000;19(4):354–364. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.4.354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banks-Wallace J, Enyart J, Johnson C. Recruitment and entrance of participants into a physical activity intervention for hypertensive African American women. Advances in Nursing Science. 2004;27(2):102–116. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200404000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parra-Medina D, D'Antonio A, Smith SM, Levin S, Kirkner G, Mayer-Davis E. Successful recruitment and retention strategies for a randomized weight management trial for people with diabetes living in rural, medically underserved counties of South Carolina: the POWER study. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2004;104(1):70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilbur J, McDevitt J, Wang E, et al. Recruitment of African American women to a walking program: eligibility, ineligibility, and attrition during screening. Research in Nursing & Health. 2006;29(3):176–189. doi: 10.1002/nur.20136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilbur J, McDevitt JH, Wang E, et al. Outcomes of a home-based walking program for African-American women. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2008;22(5):307–317. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.22.5.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Keller CS, Cantue A. Camina por Salud: walking in Mexican-American women. Applied Nursing Research. 2008;21(2):110–113. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rucker-Whitaker C, Basu S, Kravitz G, Bushnell MK, de Leon CF. A pilot study of self-management in African Americans with common chronic conditions. Ethnicity & Disease. 2007;17(4):611–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hines-Martin VF, Speck BJ, Stetson B, Looney SW. Understanding systems and rhythms for minority recruitment in intervention research. Research in Nursing & Health. 2009;32:657–670. doi: 10.1002/nur.20355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fitzgibbon ML, Prewitt TE, Blackman LR, et al. Quantitative assessment of recruitment efforts for prevention trials in two diverse black populations. Preventive Medicine. 1998;27(6):838–845. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Staffileno BA, Coke LA. Recruiting and retaining young, sedentary, hypertension-prone African American women in a physical activity intervention study. The Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2006;21(3):208–216. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200605000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang MW, Brown R, Nitzke S. Participant recruitment and retention in a pilot program to prevent weight gain in low-income overweight and obese mothers. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:424. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eakin EG, Bull SS, Riley K, Reeves MM. Recruitment and retention of Latinos in a primary care-based physical activity and diet trial: The Resources for Health study. Health Education Research. 2007;22(3):361–371. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chiang CY, Sun FK. The effects of a walking program on older Chinese American immigrants with hypertension: a pretest and posttest quasi-experimental design. Public Health Nursing. 2009;26(3):240–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2009.00776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prohaska TR, Peters K, Warren JS. Sources of attrition in a church-based exercise program for older African-Americans. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2000;14(6):380–385, iii. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-14.6.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Warren-Findlow J, Prohaska TR, Freedman D. Challenges and opportunities in recruiting and retaining underrepresented populations into health promotion research. The Gerontologist. 2003;43(Suppl 1):37–46. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.suppl_1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paschal AM, Lewis RK, Martin A, Shipp DD, Simpson DS. Evaluating the impact of a hypertension program for African Americans. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2006;98(4):607–615. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Resnicow K, Taylor R, Baskin M, McCarty F. Results of go girls: a weight control program for overweight African-American adolescent females. Obesity Research. 2005;13(10):1739–1748. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parra-Medina D, Wilcox S, Wilson DK, Addy CL, Felton G, Poston MB. Heart Healthy and Ethnically Relevant (HHER) Lifestyle trial for improving diet and physical activity in underserved African American women. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2010;31(1):92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martyn-Nemeth PA, Vitale GA, Cowger DR. A culturally focused exercise program in Hispanic adults with type 2 diabetes: a pilot study. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36(2):258–267. doi: 10.1177/0145721709358462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yancey AK, McCarthy WJ, Harrison GG, Wong WK, Siegel JM, Leslie J. Challenges in improving fitness: results of a community-based, randomized, controlled lifestyle change intervention. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006;15(4):412–429. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yancey AK, Miles OL, McCarthy WJ, et al. Differential response to targeted recruitment strategies to fitness promotion research by African-American women of varying body mass index. Ethnicity & Disease. 2001;11(1):115–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Harralson TL, Emig JC, Polansky M, Walker RE, Cruz JO, Garcia-Leeds C. Un Corazon Saludable: factors influencing outcomes of an exercise program designed to impact cardiac and metabolic risks among urban Latinas. Journal of Community Health. 2007;32(6):401–412. doi: 10.1007/s10900-007-9059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Story M, Sherwood NE, Himes JH, et al. An after-school obesity prevention program for African-American girls: the Minnesota GEMS pilot study. Ethnicity & Disease. 2003;13:54–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Story M, Sherwood NE, Obarzanek E, et al. Recruitment of African-American pre-adolescent girls into an obesity prevention trial: the GEMS pilot studies. Ethnicity & Disease. 2003;13:78–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fitzgibbon ML, Stolley MR, Schiffer L, Van HL, KauferChristoffel K, Dyer A. Hip-Hop to Health Jr. for Latino preschool children. Obesity. 2006;14(9):1616–1625. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fitzgibbon ML, Stolley MR, Schiffer L, Van HL, KauferChristoffel K, Dyer A. Two-year follow-up results for Hip-Hop to Health Jr.: a randomized controlled trial for overweight prevention in preschool minority children. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2005;146(5):618–625. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilson DK, Griffin S, Saunders RP, Kitzman-Ulrich H, Meyers DC, Mansard L. Using process evaluation for program improvement in dose, fidelity and reach: the ACT trial experience. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2009;6:79. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-6-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Escobar-Chaves SL, Tortolero SR, Masse LC, Watson KB, Fulton JE. Recruiting and retaining minority women: findings from the Women on the Move study. Ethnicity & Disease. 2002;12(2):242–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Merriam P, Tellez T, Rosal M, et al. Methodology of a diabetes prevention translational research project utilizing a community-academic partnership for implementation in an underserved Latino community. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2009;9(1):20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Keller CS, Gonzales A, Gonzales AF, Fleuriet KJ. Retention of minority participants in clinical research studies. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2005;27:292–306. doi: 10.1177/0193945904270301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hovell MF, Mulvihill MM, Buono MJ, et al. Culturally tailored aerobic exercise intervention for low-income Latinas. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2008;22(3):155–163. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.22.3.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pekmezi DW, Neighbors CJ, Lee CS, et al. A culturally adapted physical activity intervention for Latinas: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2009;37(6):495–500. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taylor-Piliae RE, Froelicher ES. Methods to optimize recruitment and retention to an exercise study in Chinese immigrants. Nursing Research. 2007;56(2):132–136. doi: 10.1097/01.NNR.0000263971.46996.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen JL, Weiss S, Heyman MB, Lustig RH. Efficacy of a child-centred and family-based program in promoting healthy weight and healthy behaviors in Chinese American children: a randomized controlled study. Journal of Public Health. 2009;32:219–229. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Frierson GM, Williams DM, Dunsiger S, et al. Recruitment of a racially and ethnically diverse sample into a physical activity efficacy trial. Clinical Trials. 2008;5:504–516. doi: 10.1177/1740774508096314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chang MW, Nitzke S, Brown R. Design and outcomes of a Mothers In Motion behavioral intervention pilot study. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2010;42(3 Suppl):S11–S21. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gaston MH, Porter GK, Thomas VG. Prime Time Sister Circles: evaluating a gender-specific, culturally relevant health intervention to decrease major risk factors in mid-life African-American women. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2007;99(4):428–438. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sharp LK, Fitzgibbon ML, Schiffer L. Recruitment of obese black women into a physical activity and nutrition intervention trial. Journal of Physical Activity & Health. 2008;5(6):870–881. doi: 10.1123/jpah.5.6.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Robinson TN, Killen JD, Kraemer HC, et al. Dance and reducing television viewing to prevent weight gain in African-American girls: the Stanford GEMS pilot study. Ethnicity & Disease. 2003;13:65–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beech BM, Klesges RC, Kumanyika SK, et al. Child- and parent-targeted interventions: the Memphis GEMS pilot study. Ethnicity & Disease. 2003;13(1 Suppl 1):S40–S53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yancey AK, Ory MG, Davis SM. Dissemination of physical activity promotion interventions in underserved populations. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;31(4 Suppl):S82. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Resnicow K, Yaroch AL, Davis A, et al. GO GIRLS!: results from a nutrition and physical activity program for low-income, overweight African American adolescent females. Health Education & Behavior. 2000;27(5):616–631. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Resnicow K, Jackson A, Blissett D, et al. Results of the healthy body healthy spirit trial. Health Psychology. 2005;24(4):339–348. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yancey AK, Tomiyama AJ. Physical activity as primary prevention to address cancer disparities. Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 2007;23(4):253–263. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]