ABSTRACT

The growing evidence of the influence of urban environment on physical activity (PA) underscore the need for novel policy solutions to address the inequality, lack of space, and limited PA resources in rapidly growing Latin American cities. This study aims to better understand the PA policy process by conducting two case studies of Bogotá’s Ciclovía and Curitiba’s CuritibAtiva. Literature review of peer- and non-peer-reviewed documents and semi-structured interviews with stakeholders was conducted. In the cases of Ciclovía and CuritibAtiva, most policies conducive to program development and sustainability were developed outside the health sector in sports and recreation, urban planning, environment, and transportation. Both programs were developed by governments as initiatives to overcome inequalities and provide quality of life. In both programs, multisectoral policies mainly from recreation and urban planning created a window of opportunity for the development and sustainability of the programs and environments supportive of PA.

KEYWORDS: Physical activity, Health promotion, Policy, Community interventions

INTRODUCTION

Over the past several decades, policymakers in large cities in Latin America—like Bogotá and Curitiba—have sought to maintain and/or improve residents’ quality of life in the face of rapid growth and urbanization. In this region, rapidly growing cities must deal with conditions like widespread inequality, lack of space, and limited recreational resources, all of which require novel policy solutions [1, 2]. Thus, to improve social well-being among the urban population, leaders have pursued changes in urban development that could impact the social determinants of health and begin to reduce inequalities related to access to transport, to recreational facilities, and to pedestrian infrastructure. At the same time, public health researchers and practitioners have increasingly recognized the influence of urban environment on healthy behaviors like physical activity (PA) [3, 4]. There is clear and strong evidence that lack of PA increases the risk for numerous chronic diseases [5]. Further, there is evidence of an association between built environmental attributes with walking and cycling [6, 7]. Likewise, urbanization and health was the focus of WHO’s "1000 cities–1000 lives" campaign, its theme for World Health Day 2010 [8].

In this context, the cases of two programs in the rapidly urbanized cities of Bogotá, Colombia, and Curitiba, Brazil, exemplify urban programs that can influence PA promotion. Bogotá is home to the world's largest Ciclovía Recreativa, in which streets are closed temporarily to motorized traffic to provide residents exclusive access for recreation and sports [9]. Curitiba has the city-wide CuritibAtiva program, which promotes, directs, and evaluates PA in sports and leisure centers, parks, squares, and schools [10, 11]. Yet, like most PA interventions in Latin America, these programs are just beginning to be evaluated as examples of urban changes with public health potential [12]. Specifically, three studies showed that adults who reported participating in the Ciclovía program were more likely to meet PA recommendations or report biking [9, 13, 14]. Likewise, a study showed that adults who reported participating in CuritibAtiva were more likely to meet PA recommendations during leisure time [10]. In fact, Ciclovía and CuritibAtiva are considered environmental and policy interventions in the category of “community-wide policies and planning” and are identified in Project GUIA as having promise for the promotion of PA in Latin America [12]. Considering that a key issue in translational research is how to develop policies and environmental changes that will apply effective or promising intervention approaches among populations at risk, this paper analyzes the historical events that led to the programs’ origination and consolidation and identifies policies and factors that may have influenced their development and sustainability. The case studies were conducted as part of the International Symposium of the Physical Activity Policy Research Network (PAPRN) and project GUIA (Guide for Useful Interventions for Activity—the project’s mission is to build cross-national partnerships to assess and build evidence-based strategies to promote PA at the community level in Brazil and Latin America. The GUIA project included a systematic review of the Latin American literature on strategies for promoting PA in the community based on the U.S. Community Guide) [15].

METHODS

Definitions

The case studies assessed different aspects of PA-related policies along all scales and sectors using the Physical Activity Policy Framework [16]. This Framework emphasizes the need to study different aspects of policies relevant to PA, and proposed a research agenda that included (1) identification of policies, (2) study of the determinants of policy, (3) study of the development and implementation of policies, and (4) study of policy outcomes. The first point in the agenda guided our main question: Which policies and factors might have influenced the development and sustainability of the Ciclovía and CuritibAtiva programs? In this paper, “policy” refers to the “legislative or regulatory action taken by federal, state, city, or local governments, government agencies or nongovernmental organizations and includes formal and informal rules and design standards that may be explicit or implicit” [16].

Context and study settings

During the second half of the twentieth century, Latin American countries (LACs) experienced rapid urbanization. For example, it is estimated that during the 1960s, more than a fifth of the rural population moved to urban settlements [17]. This phenomenon was associated with stronger demands for the provision of basic services, the worsening of the urban quality of life, and increased unemployment, poverty, and inequality [18]. The detrimental consequences of urbanization began to be recognized and, in 1976, the United Nations Habitat Conference emphasized the need for improving human settlements as a precondition for attaining a better quality of life [18]. Yet, poverty and inequality increased in LAC, with the concurrent global debt crisis and the structural adjustments that followed [19]. In the 1990s, globalization imposed further challenges. LAC underwent state reforms that included economic openness, decentralization, and striving for competitiveness [20]. Paradoxically, globalization reinforced the role of cities as a global economy needs strategic places for its functioning. Consequently, cities needed to become competitive, productive places to enter the global market and attract investments [20]. These changes transformed the previous urbanism that privileged growth at the expense of urban sprawl. This included the need for urban transformations, the provision of services, and a growing concern for the environmental impact of production and economy. In this context, the concept of sustainable cities and strategic planning acquired relevance, along with a new emphasis on environmentalism and quality of life [20].

Like cities in other LACs, Bogotá and Curitiba experienced the impact of those changes [21, 22]. At that time, Bogotá had few parks and spaces for cycling, and recreational alternatives were scarce, especially for the underprivileged [23]. In Curitiba, the growth resulting from the influx of a significant number of European immigrants exceeded expectations, and infrastructure problems became grave, marked especially by the lack of safety and schools, and the precarious conditions of access roads [22].

In this context of urbanization and its consequences, Bogotá and Curitiba experienced major urban changes during the past decades [24, 25]. Both cities have been internationally recognized for that reason and currently rank high in environmental performance [24].

Bogotá’s transformations include the recovery of public space, improvement of public transportation, and promotion of non-motorized transport (including the construction of bicycle paths, and an increase in green areas per inhabitant) [4, 25]. Bogotá is the capital city of Colombia. It is located at 2,630 m above sea level, has an average temperature of 14°C, no seasons, and an estimated 7 million residents. In 2000, the Human Development Index (HDI) for these residents was 0.81, the GINI index (a measure of inequality that varies between 0—complete equality and 1—complete inequality) was 0.57, and the city had 4.12 m2 of green area per inhabitant [26]. The current literacy rate is 96% with 18% of the residents having completed high school and 22% having more than a high-school education. Because only 20% of the households own a car, most trips inside Bogotá are by public transport (57%), but 15% are on foot, 18% are by private vehicle or taxi, and 2% are by bicycle; the remainder are multimodal [7, 27]. The prevalence of overweight/obesity in Bogotá is 48% and the prevalence of meeting PA recommendations (at least 30 min of PA during a 5-day period) is 9% during leisure time, 3% for biking for transport, and 25% for walking for transport [28].

On the other hand, Curitiba is considered a model and a pioneer in the region because of its initiatives on sustainable transportation, green spaces, air quality, and sanitation, based on a top-down, long-term urban planning approach [24]. Curitiba is the capital city of the state of Paraná, it has an estimated 1.8 million residents and a temperate climate with mild seasons. In 2000, the HDI was 0.86 and the GINI index was 0.59; the city has 46 m2 of green area per inhabitant [29]. The current literacy rate is 97%, and 38% of the population have more than a high-school education. About 70% of the households own a car. In Curitiba, the prevalence of overweight/obesity is 46%, and the percentage for meeting PA recommendations during leisure time is 14.% [30].

Data collection

Data collection was carried out through: (1) a literature review aimed at understanding and reconstructing the historical process of the programs and identifying the main actors and policies involved. The literature review included both peer reviewed and non peer-reviewed documents (i.e., policies, regulations, legislative acts, and district development plans). Detailed information about the methods and results of these systematic searches can be found elsewhere [9, 12]. (2) Semi-structured interviews.

For the Ciclovía program, we conducted a systematic review including peer-reviewed and other literature identified through literature databases, Internet and newspapers searches, and expert consultation [9]. Briefly, the first searches took place in April 2008, and follow-up searches were conducted in May 2010. The following databases were searched: LILACS, MEDLINE, MEDCARIB, PAHO, WHOLIS, and SCIELO. Search terms in English and Spanish included “Ciclovía” and “Bogotá” and combinations of “bicycling” or “cycling” and “bike path” or “bike lane”, as well as “mass/mega events” and “walking”, “biking”, or “cycling”. The process also included a Google search with the following terms “Ciclovía” and “Bogotá”. This search was complemented by specific directed searches for policies, regulations, legislative acts, and district development plans that were identified through the literature review or the experts’ consultation. The experts also provided references for non-indexed reports and documents. The materials identified during the literature search were screened and reviewed independently by one investigator and two research assistants. Reports about Ciclovía were accepted for further review if the Ciclovía of Bogotá was included. Therefore, the review excluded reports related to ciclovías from other cities and permanent bikeways.

For the case of Curitiba, the literature search included peer and non-peer-reviewed literature related to CuritibAtiva [12]. The following databases were systematically searched: Biblioteca Virtual de Saúde (which includes LILACS, MEDLINE, MEDCARIB, OPAS/OMS, PAHO, and WHOLIS), SCIELO, PubMed, CAPES (thesis database), and NUTESES (thesis database). Search terms included a combination of the following: “Curitiba”, “physical activity interventions”, “urban planning”, and “parks and recreation”. We included all the information between 1960 and 2010. Because many publications were not available online and were published before the 1960s, the search was complemented by supplementary sources (e.g., policies, regulations, legislative acts, and district development plans) which were manually searched in the following locations: Curitiba Urban Planning Institute, Curitiba Municipal Council, and Curitiba Parks and Recreation Department. After a blind review conducted by two trained reviewers, all materials not related to CurtibAtiva or the context defined in this study were excluded.

The semi-structured interviews were conducted with actors identified in the literature review as qualified to provide in-depth information. Further recruitment was also carried out using a snowball sampling [31]. For the Curitiba program, the actors had already been identified in previous formative research on the key elements in decision-making on the city’s PA programs [11].

In the case study of Bogotá, we adapted the interview guide from Eyler et al.’s [32] study of community trails. We included the main themes covered in the guide (information on the interviewees, program planning and development, funding, management and maintenance, and lessons learned), but also included some new themes (policies, experience, and opinions about the program) and used specific topics that were relevant to the Ciclovía. We also developed specific guides that suited the different types of interviewees and their involvement in the program (policy makers, managers, and members of the community). The inclusion of different types of interviewees was aimed at collecting different perspectives that could account for a bigger picture and maximize validity. Interviewees included former mayors, city council members, activists, former and current managers, recreational guides, and users. (Interview questions are available from the first author on request.)

For the Curitiba study, the interview protocol was divided into five sections: interviewee information, knowledge about the PA programs provided by the Municipal Secretary of Sports and Leisure, knowledge about CuritibAtiva, and opinions on the programs’ sustainability and reproducibility. Interviewees included CuritibAtiva users, managers, its team members, and all the sports and leisure unit managers that implement the program.

Each interview was conducted by one of the authors, either in person or by phone (Bogotá, n = 20; Curitiba, n = 19). Signed or verbal consent was collected from each informant. The Bogotá research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Universidad de los Andes; that for Curitiba was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Pontiff Catholic University of Paraná. All interviews were recorded, transcribed, and checked for accuracy.

Data analysis

Preliminary analysis, interpretation of data, and discussions between researchers took place in parallel with data collection. This process guided the type of questions asked in subsequent interviews and shaped the way the topic was addressed throughout data collection and analysis.

Data analysis followed the framework analysis technique [33] and was conducted by two of the authors for the case of Bogotá (ADC, OLS), and by one of the authors (RR) and another experienced researcher for the case of Curitiba. The stages of analysis included the following: (1) familiarization with the data (reading all transcripts and field notes); (2) inductive identification of main themes that could constitute a thematic framework; (3) development of a preliminary thematic framework using the emergent themes; (4) indexing of a few transcripts to refine the framework (this included grouping some co-occurring codes by hierarchies based on the interview guides when possible); (5) indexing of all transcripts according to the framework, and development of memos (persistent co-occurring codes were documented on memos to look for associations); (6) development of charts grouped by each theme across all respondents that included summaries and verbatim texts (charts were used to make comparisons and associations between themes and interviewees). In order to maximize validity, special emphasis was placed on looking for contrasts and opposing views and negative-case sampling. (7) Mapping and interpretation of the data set by making comparisons and contrasts between interviewees and themes (looking for connections and explanations for different perspectives, and developing diagrams that could account for the gathered information). All the information was independently summarized and cross-compared. The analysis was carried out using the NUDIST QSR N6 software [34].

RESULTS

History

Bogotá’s Ciclovía

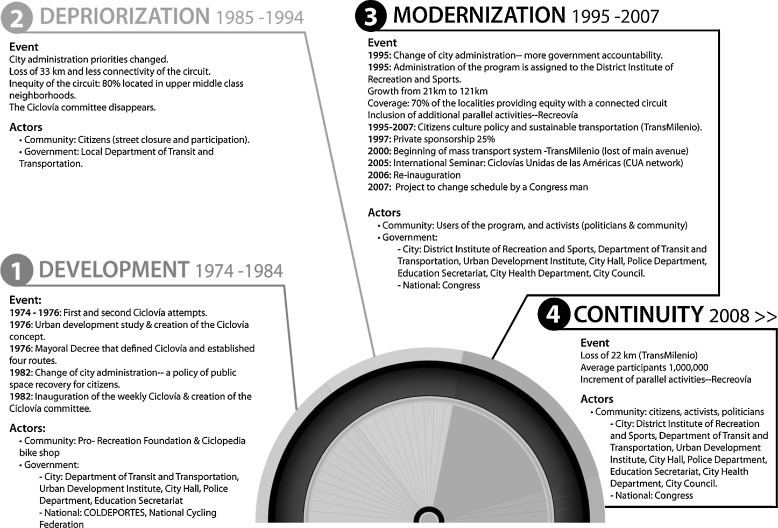

The first Ciclovía trial took place in December 1974 [21, 35] when a group of activists and university students, supported by the city departments of urban development and transportation, took over several main streets with their bicycles. The Ciclovía, however, did not progress far beyond this initial event due to a lack of better organization [35] (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Historical periods and actors in Bogotá’s Ciclovía, 1974–2010

An opportunity for change arose in 1982 when the mayor suggested that giving public space back to the citizens could partially counteract inequality [23]. As a result, the administration formally opened the Ciclovía under the direction of the Department of Transportation, and the program continued on a weekly basis [35]. A Ciclovía committee was formed made up of community activists, the police, the departments of transportation and education, the Colombian Institute of Sports and the National Cycling Federation [35]. By 1984, the Ciclovía was 54 km long [21, 35].

Between 1985 and 1995, the administrations’ priorities changed and the Ciclovía committee stopped functioning. During this period, a reduction in the Ciclovía’s length also led to inequality in that 80% of the program served the wealthier part of the city [21]. By 1995, the Ciclovía had diminished by an estimated 33 km (personal communication, Instituto Distrital de Recreación y Deporte), and the circuit lacked connectivity [21]. Yet despite these problems, the community continued closing and using the streets.

From 1995 to 2003, a succession of mayors promoted new cultural practices, improved infrastructure [4, 25, 36], and strengthened the Ciclovía, and in 1996, program management was reassigned to the District Institute of Recreation and Sports [35]. This decision was accompanied by a new approach to the program, one aimed at recreation, the promotion of well-being, PA, and the provision of healthy options for leisure time. The length of the Ciclovía was also increased to 81 km in 1996 and then to 121 km in 2000 (personal communication, Instituto Distrital de Recreación y Deporte).The north (high-middle income) and south (low-middle income) sectors of the city were reconnected by a continuous circuit, and 70% of the administrative districts were covered by the program [21]. New activities were implemented, such as the Recreovía, a complementary program of free PA classes offered and run by certified instructors that take place in public spaces, near or along the Ciclovía corridor. Currently, there are 30 Recreovía points [35]. Another innovation were the temporary modules located next to the Ciclovía corridor for screening for levels of PA and risk factors and for providing counseling by health personnel [35].

By 2010, the Ciclovía program had expanded to encompass nine sectors including education, environment, health, police, sports, culture and recreation, transport, urban planning, and government. The human resources include administrative personnel, guardians or guides in charge of orienting users, organizing logistics, managing the route, providing first aid, and running communications, middle and high school students that are completing their mandatory community service requirements and help signaling traffic, informing users and supporting recreational activities, temporary vendors, and support personnel. The circuit’s total length is now 97 km, its annual costs are about $1.7 million USD (public funding 75%), and its attendance average ranges from 600,000 to 1,400,000 users per event. The program is constantly promoted to the public in general and various sectors of the society through mass media (radio, newspapers, television, internet), brochures and billboards, permanent traffic signs that signal the Ciclovía corridors, and through the organization of special events.

Curitiba’s CuritibAtiva

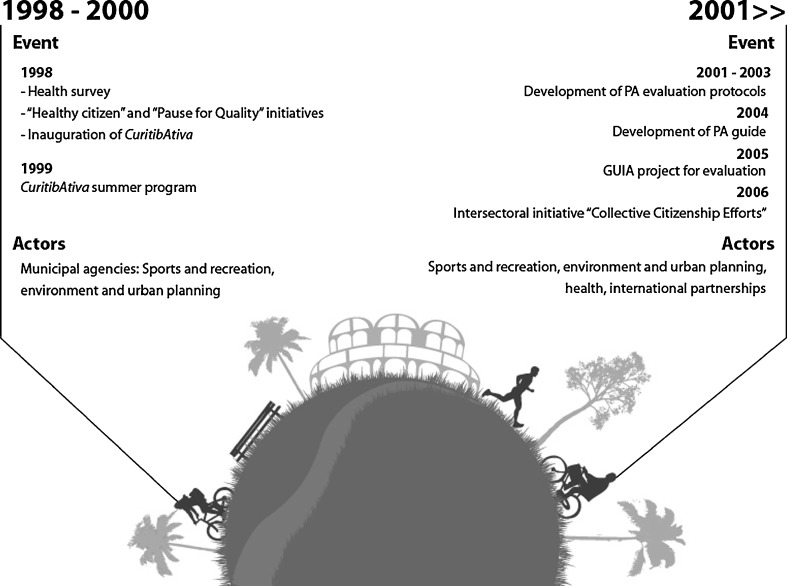

By 1998, after a survey placed Curitiba among the Brazilian cities with the highest prevalence of cardiovascular disease [37], several municipal agencies focused on making Curitiba a healthier city by developing initiatives like the “Healthy Citizen” and “Pause for Quality,” which set a precedent for today’s CuritibAtiva [38] (Fig. 2). Such initiatives also showed that Curitiba’s municipal staff had little knowledge about PA promotion in the public health context [38]. This situation, coupled with the willingness of a group of sports and leisure staff to work toward improving the city’s health ranking, drew attention to the need for a network that could provide opportunities to engage in PA [39].

Fig 2.

Historical periods and actors in Curitiba’s CurtibAtiva, 1998–2010

Initially, the CuritibAtiva program consisted of distributing educational information on movement, stretching, weight loss, strength building, and asthma management in public and private schools, public agencies, private companies, street markets, shopping malls, soccer stadiums, and sports and leisure centers [40]. Between 1998 and 2000, CuritibAtiva program staff members distributed brochures, and evaluated the materials’ effect on the population’s behavior through a survey in four city locations. According to the survey, 33% of those reading the brochure reported positive changes in their PA-related behavior [38, 39].

The CuritibAtiva program organizers also began implementing activities in the sports and leisure centers, including physical conditioning, gymnastics, water activities, community entertainment, dancing, running, and school games [39]. In 1999, the CuritibAtiva summer program was launched, which consisted of PA classes in parks, squares, parking lots, and sports and leisure centers. Between 2001 and 2003, the administrators designed protocols to assess the physical fitness of adults, older adults, and children and adolescents [39]. In 2004, program organizers created a PA guide.

In June 2006, as part of a municipal government focus on overcoming inequality and strengthening public policies that could positively impact the development of local communities and health and quality of life indicators, the program implemented a new intersectoral initiative, “Collective Citizenship Efforts”. This program, which consists of a street market-like event that offers such free public services as documentation, nutritional education, haircuts, and financial and vocational orientation, became part of the Municipal Secretary of Health’s broader policy for health promotion [41]. On weekends, the program’s Health Stand offers blood pressure measurement, glucose, cholesterol, flexibility and muscle strength testing, and anthropometric measurement. Such services are part of the mayor’s new emphasis on refocusing the city’s health promotion.

By 2010, the CuritibAtiva program had expanded to encompass five sectors. Although Sports and Recreation is responsible for the program, key partners include health, environment and preservation, security, and urban planning. The CuritibAtiva staff (n = 5) coordinates, organizes, and runs all the activities. These activities take place in the city’s sports and leisure infrastructure that includes parks, plazas, bike lanes, and 28 sports and leisure centers within the nine districts of Curitiba [10]. Physical educators hired by the Sports and Leisure Department lead all activities, which occur in a short-term basis (e.g., Rustic Race, the marathon, and Dance Curitiba), and on an on-going basis (e.g., PA classes, Night Bikers, and the walking circuit) [11]. These professionals (n = 144) are distributed in each district, coordinated by a sports and leisure manager. The financial resources come from the annual budget of the Municipal Secretary of Sports and Leisure. The number of participants ranges from 50,000 to 200,000 per year [11]. CuritibAtiva is promoted to the population through different strategies such as printed material (brochures, flyers, posters), partnerships with the private sector that advertise the program (i.e., supermarkets), and handing out of advertisement leaflets in the sport centers.

Policies: Bogotá’s Ciclovía

Sports and recreation

National

The National Plan for Recreation (1986), aimed at the democratization of recreation, was articulated through health policies, urban development, community participation, and renovation of areas affected by violence [21, 42]. In addition, the National Constitution (1991) established recreation and sports as the right of all citizens and declared their promotion and funding to be a state responsibility [43]. This legislation contributed to a change in the administration’s view of the Ciclovía, from simply that of an expense to a program that guarantees the provision of recreation and sports as a constitutional right. The subsequent Sports Law (1995) allocated national and local funds, and included the creation of spaces for recreation and sports within urban settings to promote healthy habits and improve quality of life especially for vulnerable populations [44] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Ciclovía program, Bogotá and CuritibAtiva, Curitiba

| Characteristics | Bogotá Ciclovía | Curitiba CuritibAtiva |

|---|---|---|

| Year of inauguration | 1974 | 1998 |

| Number of participants | 600,000–1,400,000 per event | 50,000–200,000 |

| Costs | 1.7 million US dollars per year | NA |

| Sectors involved | Education, environment, health, security, sports and recreation, transport, culture and urban planning | Sports and recreation, health, security, environment and preservation, and urban planning |

| Coordinator of the program | Sports and recreation | Sports and recreation |

| Enablers | Policies at several sectors and at the local and national level | Policies at several sectors and at the local and national level |

| The program circuit connects low and high socioeconomic neighborhoods | Coverage among wealthy and poor areas | |

| Community and local government support | Community and local government support | |

| Use of existing infrastructure | Use of existing infrastructure | |

| Complementary activities in addition to the closure of the streets which contributes to the sustainability and creativity of the program | ||

| Barriers | Traffic from private and public transport | Availability of infrastructure |

| Some businesses along the corridor | Clear identity of program by the users | |

| Budget | Budget definition within city’s financial planning |

Local level

On the local level, policies include the creation of the District Institution for Recreation and Sports (1978) [35], and the district development plans of the 1995–2003 administrations, which promoted recreation and sports in public spaces, recovery of public space, sustainable transportation, construction of a human scale city, optimization of leisure time, conviviality, identity, quality of life, and social justice [45–47]. Another initiative, “For the Bogotá We Want” included the goal of strengthening the Ciclovía as part of prioritizing “conviviality and security” [47]. The 2009 declaration of the Ciclovía as a program of cultural, sports, and social interest also served to further protect the program [48].

Urban planning sector

Local level

The link between urban planning policies and the Ciclovía appears to be more direct. First, the 1976 district decree formally defined the temporary Ciclovía and designated its route [49]. Second, the 1982–1984 “Bogotá for the Citizen” policy framed the decision of implementing the Ciclovía as a permanent program [23]. This policy specifically considered public spaces to be an inalienable public good and a tool for improving people’s quality of life [23]. The Ciclovía was articulated with these values because it was seen as a solution to the problems engendered by unplanned urbanization [23]. Third, the 1995–1998 district development plan “Shape the City” included the Ciclovía as a strategy for recovering public space and contemplated changing its administration from the transportation sector to recreation and sports and urban development [45]. This change contributed to the program’s consolidation.

Transportation sector

National level

The 2002 National Transit Code included a definition for “bicycle” and two types of roads specially destined for cycling: Ciclovía and Ciclorruta (bike lane) [50].

Local level

Three district development plans (1995–1998, 1998–2001, and 2008–2010) included specific policies that may have influenced the Ciclovía. For example, the “Shape the City” (1995–1998) initiative accorded equal consideration to pedestrians and motor vehicles alike, an idea implicit in the conceptualization of Ciclovías as the recovery of streets for and by citizens [45]. Likewise, the “Bogotá that We Want” initiative (1998–2001) promoted sustainable transport, including bicycles [47]. Therefore, although the Ciclovía is not intended to be a means of transportation, by supporting bicycling and trying to increase the status of bicycles, it may have had an impact on people’s participation in the program. On the other hand, this administration also implemented a bus rapid transit system called the TransMilenio [25], which, although recognized as efficient and well organized, was constructed along several important corridors and thus affected the Ciclovía’s length and connectivity [51].

Health sector

National level

The influence of health policies on the Ciclovía has been mainly indirect. In fact, the health sector role has centered mostly on the provision of medical care. Recently, however, the public health potential of the program has begun to receive recognition. For instance, the National Plan of Public Health (2007) and the Law on Obesity (2009) include the promotion of temporal spaces for recreation like Ciclovías as a strategy for reducing the burden of chronic diseases [52, 53].

Culture sector

National level

Since 2007, a bill has been pending in the Congress to declare the Ciclovía a cultural patrimony of the nation. This bill aims at promoting and protecting the program and guaranteeing the allocation of budget to maintain its quality and coverage [54].

Local level

One pillar of the 1995–1998 administration was the “Culture of Citizenship” initiative. This policy understood public space as a site for promoting changes in citizen behavior and appropriation of the city [36, 45]. Given that the Ciclovía constituted a viable space in which to promote these values, this policy may have helped reinforce the program.

Policies: Curitiba’s CuritibAtiva

Three factors influenced Curitiba’s sports and leisure structure that may have also affected the development of CuritibAtiva: (1) an increase in the creation of public spaces for physical activities and leisure; (2) the influence of urban planning in the form of more available public space and easier access through efficient public transportation; and (3) the decentralization of major services, including leisure and sports activities [22, 40] (Table 1).

Urban planning sector

Local level

The institutionalization of urban planning in Curitiba began with the development of a judicial–institutional structure in the 1970s [22]. Curitiba’s first pre-urban plan was followed by the inauguration of Passeio Público Park, one of the most popular leisure sites in the city. Then a development plan proposed that parks should be created as areas for leisure and the conservation of larger species [22]. Nonetheless, although these green areas were seen as symbols of urban quality of life, their main function was ornamentation [55].

Transportation sector

Local level

Public transportation in Curitiba is the result of a refinement process initiated in the 1970s that currently serves as an example for other cities [56]. The system was designed with two main arteries connecting North to South and East to West so the city’s limits may be accessed through public transportation. Along these arteries major commuting stations are located along with public facilities, which provide access to several services at no cost [11]. This structure was one of the bases for providing PA classes which was embraced as part of the CuritibAtiva program after 1998.

Environment sector

Local level

In Curitiba, green area per resident increased from less than 1 m2 in the 1960s [57] to approximately 46 m2 per resident today [29]. Most parks in Curitiba were created after a change in the zoning and a land use law [58, 59]. Not only did this legislation transform such areas into recreation and leisure locations, it motivated the Institute of Research and Urban Planning and the Department of Parks and Squares to begin preempting river shore areas and inhabited spaces for park creation.

One important milestone in the consolidation of environmental legislation was Law 7.447/1990, which regulated the usage and conservation of areas considered heritage sites or natural landmarks, to protect the ecosystem, educate people about the environment, enable scientific research, and allow recreation with nature [59–61]. Because of these actions, by the 1990s, Curitiba had become the environmental capital of Brazil. The creation of public spaces like parks and squares became an important stimulus for residents to engage in PA.

The increase of green area gave a unique venue for delivering services and also for leisure activities. These areas were used by the CuritibAtiva planners for PA classes, information materials and mass campaign initiatives (e.g., walking and running events) that are regularly offered in parks, squares, and other green public areas.

Physical education sector

Local level

Since the 1960s, physical education (PE) has taken place in Curitiba’s parks and squares [39]. In 1971, after Law 5692 mandated that municipalities offer primary and middle school education [39], PE grew strong in Curitiba, mainly through sports and the development of projects to increase the population’s opportunities for leisure [39]. Because easily accessible public spaces for physical and cultural activities were still scarce during the 1970s, the government built more squares, parks, and sports centers with appropriate infrastructure [39]. Furthermore, the Institute of Research and Urban Planning transformed the squares into recreational units or “animation axes”, providing them with several types of special equipment [40].

In September 1995, the office of the Municipal Secretary of Sports and Leisure was created as a separate entity with its own budget. Its responsibilities included formulating, planning, and implementing municipal sports and leisure policies. The development of physical education scenarios was critical for the CuritibAtiva program creation, implementation, and sustainability. The experience and structure that developed over 30 years in those scenarios was used to design and deliver the activities that are currently the core of CuritibAtiva.

CONCLUSIONS AND LESSONS LEARNED

The development and sustainability of both programs has been influenced by policies at different sectors, mainly sports and recreation and urban planning, which contributed to create a window of opportunity for the development and sustainability of the programs. In addition, both programs were identified by political leaders and local governments as initiatives that were in line with policies aimed at overcoming inequalities and providing quality of life for the citizens. In both cases, political changes with successions of administrators with common views contributed to the expansion and sustainability of the programs. It is important to underscore the creativity and efficiency of Ciclovía and CuritibAtiva in which resources are optimized by developing the programs within existing public infrastructures (streets, parks, markets, and plazas). Nonetheless, main barriers that need to be continually addressed include, in the case of the Ciclovía, public and private traffic’s conflicting priorities, and the perception of a decrease in sales among the business in the corridor. Likewise, for CuritibAtiva, limitations in the availability of existing infrastructure, budget definition within the city’s financial planning, and a need for a clearer recognition of the identity of the program by the users are the main barriers.

What lessons from these two Latin American programs could be potentially useful for other cities and countries?

Policies at the local and national level with multisectoral collaboration are necessary for the development and sustainability of massive programs with potential impact on PA promotion.

In some cases, practice-based evidence accelerates more quickly than evidence-based practice. For example, the Ciclovía has now been replicated in at least 98 cities of the Americas [8, 9, 62], yet only a few well-done research studies have been conducted on the effects of Ciclovía. One could argue that the researchers need to catch up with the practitioners.

The interaction of community and government is very significant for the sustainability of the programs. Both are necessary but neither is sufficient on its own. For example, the community has been a great advocate for Ciclovía, by reclaiming the streets every week. This continued support makes it difficult for any policy-maker to risk making an unpopular decision concerning the program. On the other hand, when the program was opposed by business owners, administrations who were convinced of its benefits took actions to preserve it.

Programs like the Ciclovía and CuritibAtiva show promise as a way to address the social determinants of health, in particular to reduce inequalities.

Ciclovía and CuritibAtiva show that programs with public health benefits can exist in the realms of sectors different from health, such as recreation and sports, urban planning, or education. Health practitioners and researchers should look for and build on those programs, especially where resources are limited.

Lastly, it is important to underscore that the ongoing evaluation of these programs has involved international networks and multidisciplinary groups with partnerships between researchers, practitioners, stakeholders, programs coordinators, and community leaders. These partnerships are helping to provide public health evidence of the effectiveness of Ciclovía and CuritibAtiva [9], which in turn could help policy development, dissemination, and sustainability of the programs [63].

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply indebted to all the people who contributed to this paper by providing information. In alphabetical order they are Lucy Barriga, Miguel Ignacio Bermúdez, Carlos Orlando Ferreira, Rocío Gamez, Juan Camilo Hoyos, Edwin Martínez, Felipe Montes, Guillermo Peñalosa, Mauricio Ramos, Augusto Ramírez Ocampo, Oscar Ruiz, Alfonso Segura, and Roberto Zarama. The authors also want to thank Laura Fernanda Romero and Natalia Salamanca who transcribed all the interviews, James Merrel and Roy Nijhof for their valuable comments on earlier versions of this manuscript, and Diana Fernández and Gustavo Espinel for designing the figures. We also are grateful for the support from Amy Eyler and Ciro Romélio Rodriguez-Añez. This study was funded through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) contract U48/DP000060 (Prevention Research Centers Program) Physical Activity Policy Research Network and Project GUIA (Guide for Useful Interventions for Activity). It also received funding from Colciencias grant 519 2010. Sarmiento received funding from the fund for sustainable mobility research projects by La Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá.

Footnotes

Implications

Practice: Building on other sectors’ initiatives (i.e., sports and recreation, culture, education, urban planning) can be a successful strategy for promoting physical activity where resources are limited.

Policy: Policies at the local and national level that incorporate multisectoral collaborations are essential for the development and sustainability of massive programs that promote physical activity.

Research: There is a need for evaluating physical activity community programs and catching-up with practice-based evidence, which can be enhanced by the joint work of international networks and multidisciplinary groups.

Contributor Information

Adriana Díaz del Castillo, Phone: +57-1-3394949, FAX: +57-1-3324281, Email: addiaz@uniandes.edu.co.

Olga L Sarmiento, Phone: +57-1-3394949, FAX: +57-1-3324281, Email: osarmien@uniandes.edu.co.

Rodrigo S Reis, Phone: +55-41-80240 050, Email: reis.rodrigo@pucpr.br.

Ross C Brownson, Phone: +1-314-3629641, Email: rbrownson@gwbmail.wustl.edu.

References

- 1.Jacoby E, Bull F, Neiman A. Rapid changes in lifestyle make increased physical activity a priority for the Americas. Revista Panamericana de Salud Publica. 2003;14:226–228. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892003000900002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pan American Health Organization. (2011). Regional strategy and plan of action on an integrated approach to the prevention and control of chronic diseases. Retrieved January 5, from http://www.paho.org/english/ad/dpc/nc/reg-strat-cncds.pdf.

- 3.Owen N, Humpel N, Leslie E, Bauman A, Sallis JF. Understanding environmental influences on walking: review and research agenda. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;27:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parra D, Gomez L, Pratt M, Sarmiento OL, Mosquera J, Triche E. Policy and built environment changes in Bogotá and their importance in health promotion. Indoor and Built Environment. 2007;16:344–348. doi: 10.1177/1420326X07080462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Department of Health and Human Services. (1996). Physical activity and health: a report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

- 6.Li F, Fisher KJ, Brownson RC, Bosworth M. Multilevel modelling of built environment characteristics related to neighbourhood walking activity in older adults. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2005;59:558–564. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.028399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cervero R, Sarmiento OL, Jacoby E, Gomez LF, Neiman A. Influences of built environments on walking and cycling: lessons from Bogotá. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation. 2009;3:203–226. doi: 10.1080/15568310802178314. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. (2010). World Health Day—7 April 2010. Retrieved March 8, from http://www.who.int/world-health-day/2010/en/index.html.

- 9.Sarmiento OL, Torres A, Jacoby E, Pratt M, Schmid T, Stierling G. The Ciclovía-recreativa: a mass recreational program with public health potential. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2010;7:S163–S180. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.s2.s163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reis R, Hallal P, Parra D, et al. Promoting physical activity through community-wide policies and planning: findings from Curitiba, Brazil. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2010;7:137–145. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.s2.s137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ribeiro I, Torres A, Parra D, et al. Using logic models as iterative tools for planning and evaluating physical activity promotion programs in Curitiba, Brazil. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2010;7:155–162. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.s2.s155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoehner CM, Soares J, Perez DP, et al. Physical activity interventions in Latin America: a systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;34:224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomez LF, Mateus JC, Cabrera G. Leisure-time physical activity among women in a neighbourhood in Bogotá, Colombia: prevalence and socio-demographic correlates. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2004;20:1103–1109. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2004000400026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomez LF, Sarmiento OL, Lucumi D, Espinosa G, Forero R. Prevalence and factors associated with walking and bicycling for transport among young adults in two low income localities of Bogotá, Colombia. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2005;2:445–449. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pratt M, Brownson RC, Ramos LR, et al. Project GUIA: a model for understanding and promoting physical activity in Brazil and Latin America. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2010;7(Suppl 2):S131–S134. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.s2.s131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmid T, Pratt M, Witmer L. A framework for physical activity policy research. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2006;3:20–29. doi: 10.1123/jpah.3.s1.s20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varela, C. (1998). La ciudad latinoamericana en nuestros días. Revista austral de ciencias sociales, 19–27.

- 18.United Nations. (2010). Habitat: United Nations conference on human settlements. Vancouver. Retrieved June 18, from http://www.unostamps.nl/subject_habitat_conference_i.htm.

- 19.Gershman J, Irwin A. Getting a grip on the global economy. In: Yong J, Millen JV, Irwin A, Gershman J, editors. Dying for growth. Monroe: Common Courage; 2000. pp. 11–43. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carrión F. Las nuevas tendencias de urbanización en América Latina. In: Carrion F, editor. La ciudad construida. Urbanismo en América Latina. Quito: Flacso; 2001. pp. 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gómescásseres, T. (2003). Deporte, juego y paseo dominical: la recreación en espacios públicos urbanos, el caso de la Ciclovía de Bogotá. Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

- 22.Menezes C. Desenvolvimento urbano e meio ambiente: a experiência de Curitiba. Campinas: Papirus; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramírez, A. (1983). La ciudad para el ciudadano. In: Ciclovías, Bogotá para el ciudadano. Bogotá: Benjamín Villegas.

- 24.Economist Intelligence Unit. (2011). Latin American Green City index. Retrieved January 5, from http://www.siemens.com/entry/cc/features/greencityindex_international/all/en/pdf/report_latam_en.pdf.

- 25.Montezuma R. The transformation of Bogotá, Colombia 1995–2000. Investing in citizenship and urban mobility. Global Urban Development. 2005;1:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gomez LF, Sarmiento OL, Parra DC, et al. Characteristics of the built environment associated with leisure-time physical activity among adults in Bogota, Colombia: a multilevel study. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2010;7(Suppl 2):S196–S203. doi: 10.1123/jpah.7.s2.s196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá. (2011). Movilidad de bicicletas en Bogotá. Retrieved January 5, from http://camara.ccb.org.co/documentos/5054_informe_movilidad_en_bicicleta_en_bogota.pdf.

- 28.Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar. (2011). Encuesta Nacional de Salud Nutricional de Colombia 2005. Retrieved January 11, from http://www.icbf.gov.co/icbf/directorio/portel/libreria/pdf/1ENSINLIBROCOMPLETO.pdf.

- 29.IPPUC. (2011). Áreas verdes por habitantes e por barrio, em Curitiba 2008. Retrieved January 18, from http://www.ippuc.org.br/Bancodedados/Curitibaemdados/anexos/2008_Áreas%20Verdes%20por%20Habitante%20e%20por%20Bairro%20em%20Curitiba.pdf.

- 30.Moura E, de Morais Neto O, Carvalho Malta D, et al. Vigitel Brasil 2008: Vigilância de fatores de risco e proteção para doenças crônicas por inquérito telefônico nas capitais dos 26 estados brasileiros e no Distrito Federal (2006) Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia. 2008;11(suppl 1):20–37. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Balbach, E. (2011). Using case studies to do program evaluation. Retrieved January 5, from http://www.case.edu/affil/healthpromotion/ProgramEvaluation.pdf.

- 32.Eyler, A., Brownson, R. C., Evenson, K. R., Levinger, D., Maddock, J. E., Pluto, D. et al. (2009). Policy influences on community trails development. Available at: http://prc.slu.edu/paprn.htm#1. Accessibility verified: April 6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Spencer RG, editors. Analyzing qualitative data. London: Routledge; 1994. pp. 173–193. [Google Scholar]

- 34.QSR International. (2002). N6 NUD*IST 6.

- 35.Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá D.C. (2007) Instituto Distrital de Cultura y Turismo. La ciclovía: laboratorio para el futuro. Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá D.C.

- 36.Pizano L. Bogotá y el cambio. Percepciones sobre la ciudad y la ciudadanía. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Universidad de Los Andes; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lotufo PA. Premature mortality from heart diseases in Brazil. A comparison with other countries. Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia. 1998;70:321–325. doi: 10.1590/S0066-782X1998000500003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sawaf C, Cassou JC. Curitibativa programa de incentivo à atividade física da cidade de Curitiba. In: Kruchleski S, Rauchbach R, editors. Curitibativa gestão nas cidades voltadas à promoção da atividade física, esporte, saúde e lazer: avaliação, prescrição e orientação de atividades físicas e recreativas, na promoção da saúde e hábitos saudáveis da população curitibana. Curitiba: Rauchbach; 2005. p. 150. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cassou JC, Grande D, Kruchleski S, Rauchbach R, Siqueira JE. Políticas públicas de atividade física. In: Siqueira JE, Cassou JC, editors. Curitibativa: política pública de atividade física e qualidade de vida de uma cidade: avaliação, prescrição, relato e orientação da atividade física em busca da promoção da saúde e de hábitos saudáveis na população de Curitiba. Curitiba: Gráfica e Editora Venezuela; 2008. p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walter M. Políticas públicas e descentralização do esporte e lazer da prefeitura municipal de Curitiba: gestão 1997–2000 e 2001–2004. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação Física. Curitiba: Universidade Federal do Paraná; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krempel MC, Piloto VRBS, Poletto V. Mutirão da cidadania. In: Siqueira JE, Cassou JC, editors. Curitibativa política pública de atividade física e qualidade de vida de uma cidade: avaliação, prescrição, relato e orientação da atividade física em busca da promoção da saúde e de hábitos saudáveis na população de Curitiba. Curitiba: Editora Venezuela; 2008. p. 90. [Google Scholar]

- 42.República de Colombia. (2011). Decreto 515 de 1986. Retrieved January 5, from http://www.pereira.gov.co/docs/2009/Normatividad/1986/Decreto_515.pdf.

- 43.República de Colombia. (1991). Constitución Política de Colombia. Retrieved January 5, 2011, from http://wsp.presidencia.gov.co/Normativa/Documents/ConstitucionPoliticaColombia_20100810.pdf.

- 44.Congreso de la República de Colombia. (2011). Ley 181 de 1995. Retrieved January 5, from http://www.secretariasenado.gov.co/senado/basedoc/ley/1995/ley_0181_1995.html.

- 45.Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá. (2011). Departamento Administrativo de Planeación Distrital. Formar Ciudad. Plan de desarrollo económico, social y de obras públicas para Santa Fe de Bogotá D.C. 1995–1998. Retrieved January 5, from http://www.alcaldiabogota.gov.co/sisjur/normas/Norma1.jsp?i=2393#1.

- 46.Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá. (2011). Departamento Administrativo de Planeación Distrital. Bogotá Sin Indiferencia. Un compromiso social contra la pobreza y la exclusión. Plan de Desarrollo económico, social y de obras públicas. Bogotá D.C. 2004–2008. Retrieved January 5, from http://www.cideu.org/site/go.php?id=499.

- 47.Concejo de Bogotá. (2011). Acuerdo 6 de 1998. Retrieved January 5, from http://www.alcaldiabogota.gov.co/sisjur/normas/Norma1.jsp?i=535.

- 48.Concejo de Bogotá. (2010). Comisión segunda permanente de gobierno. Informe de actividades mes de mayo 2009 [Report of activities. May 2009]. Retrieved February 15, from concejodebogota.gov.co/…/20090701/…/20090701090058/informe_de_mayo.pdf.

- 49.Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá. Decreto 566 de 1976.

- 50.Congreso de la República de Colombia. (2011). Ley 769 de 2002. Retrieved January 5, from http://www.alcaldiabogota.gov.co/sisjur/normas/Norma1.jsp?i=5557.

- 51.Concejo de Bogotá. (2011). Acuerdo 308 de 2008. Retrieved January 5, from http://www.alcaldiabogota.gov.co/sisjur/normas/Norma1.jsp?i=30681.

- 52.Congreso de la República de Colombia. (2011). Ley 1355 de 2009. Retrieved January 5, from http://www.mij.gov.co/normas/2009/l13552009.htm.

- 53.Ministerio de la Protección Social. (2011). Plan Nacional de Salud Pública. Decreto 3039 de 2007. Retrieved January 5, from http://www.minproteccionsocial.gov.co/Normatividad/DECRETO%203039%20DE%202007.PDF.

- 54.Silva, V. (2011). Proyecto del Ley 071 de 2007 por medio de la cual se declara el “Programa de ciclovía y recreovía de Bogotá”, como patrimonio cultural vivo de la Nación y se dictan otras disposiciones. Retrieved January 5, from ftp://ftp.camara.gov.co/secretaria/debate2/P.L.071-2007C%20(CICLOV%C3%8DA%20Y%20RECREOVIA).doc.

- 55.Plano Municipal de Controle Ambiental e Desenvolvimento Sustentável. Curitiba: Secretaria Municipal de Meio Ambiente; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 56.IPPUC (2008). História do planejamento urbano. Retrieved November 28, from http://www.ippuc.org.br/pensando-a-cidade/index_hist_planej.htm.

- 57.Rechia S. Parques públicos de Curitiba: a relação cidade-natureza nas experiências de lazer. Campinas: Faculdade de Educação Física, Universidade Estadual de Campinas; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 58.PMC. (2011). Cria o Instituto de Pesquisa e Planejamento Urbano de Curitiba. Lei Municipal 2660/65. Retrieved January 5, from http://domino.cmc.pr.gov.br/contlei.nsf/baac9fc8c6760aa5052568fc004fc17e/27bd991359fee5980325690300765232?OpenDocument.

- 59.PMC. (2011). Dispõe sobre o zoneamento urbano de Curitiba. Lei Municipal 4199/72. Retrieved January 5, from http://domino.cmc.pr.gov.br/contlei.nsf/735cd5bfb1a32f34052568fc004f61b8/826188eeab86e85b032569030075ce7a?OpenDocument.

- 60.Oliveira D. Curitiba e o mito da cidade modelo. Curitiba: Editora da UFPR; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 61.PMC. (2011). Dispõe sobre a política de proteção, conservação e recuperação do meio ambiente, revoga a Lei 7447/90. Curitiba PMD Lei no. 7833/91. Vol 7833/91. Retrieved January 5, from http://domino.cmc.pr.gov.br/contlei.nsf/4661c5926d05cf08052568fc004fc17f/c70446a95e3f2817032569030074f62f?OpenDocument.

- 62.Pan American Health Organization Regional Council on Healthy Eating and Active Living and Non-Communicable Disease Unit, La Vía RecreaActiva de Guadalajara, Schools of Medicine and Engineering of the University of the Andes Bogotá Colombia, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Ciclovía de Bogotá. What is the current status of Ciclovías Recreativas in the Americas? In: Ciclovia Recreativa Implementation and Advocacy Manual. Retrieved January 5, 2011, from http://cicloviarecreativa.uniandes.edu.co/english/introduction.html.

- 63.Roussos S, Fawcett S. A review of collaborative partnerships as a strategy for improving community health. Annual Review of Public Health. 2000;21:369–402. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]