Abstract

Overweight and obesity are common challenges facing pediatric clinicians. Electronic health records (EHRs) can impact clinician behavior through the presentation of relevant, patient-specific information during clinical encounters, potentially improving clinician recognition and management of overweight/obesity in children. Little research has been published evaluating the impact of EHR-facilitated decision support on the treatment of obesity in children. The main objectives of our community clinician-led project are: 1) to build customized, evidence-based decision support into an EHR; 2) To evaluate the impact of decision support on the identification and treatment of overweight and obese children; and 3) to improve behavior around screening for obesity-related comorbidities. Through a clinician-led consensus process, we customized end user templates in the commercially-available EHR at an urban community health center with a known high prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity. Evidence based decision support was build into the screens to prompt clinicians to identify and address overweight and obesity, as well as for related comorbidities. Pre/post measures will be used to evaluate the impact of these tactics on clinician behavior. The customized EHR templates took longer than anticipated to develop, but are now being used by pediatric clinicians at the health center. Feedback to date suggests that clinicians find the evidence based decision support useful at the point of care, especially around ordering recommended screening tests. Clinicians must be active participants in the design of decision support in order for it to impact their behavior. Off-the-shelf EHR products do not automatically come with comprehensive functionality to support evidence-based interventions around clinician behavior. Modifications are needed to achieve the full promise of health information technology as it relates to delivering high quality, patient-centered, for underserved populations.

KEYWORDS: Obesity, Electronic health records, Primary care, Pediatrician, Children, Screening, Guidelines, Clinical decision support

BACKGROUND

A key function of electronic health records (EHRs) is to impact clinician behavior through the synthesis and presentation of relevant, patient-specific information during a clinical encounter. Clinical decision support rooted in evidence-based guidelines aids medical decision making, which potentially improves care by influencing clinician, and in some cases, patient behavior [1, 2]. A review of trials on clinical decisions support systems (CDSS) included only three pediatric studies [3]. Of those, two included an electronic component addressing vaccine delivery [4, 5]. There has been some progress developing electronic decision support for obese adults [6, 7], but this topic is novel in pediatrics. We are aware of just one other pediatric effort that was conducted in the US [8].

The primary care office is an ideal setting for identification and treatment of pediatric overweight/obesity and its comorbidities. Although recent guidelines address recommended screening and treatment, awareness of and adherence to these guidelines are unclear. Clinicians report a low sense of self-efficacy in addressing obesity [9]. Effective provision of training and tools could increase perceived confidence [10].

We describe an ongoing, clinician-initiated project aimed at developing an electronic clinical decision support system to foster use of evidence-based practice recommendations for outpatient, pediatric weight management and cardiovascular (CV) risk reduction. Off the shelf, the commercially available EHR in use at the health center lacked meaningful guidance on best practices for managing overweight children. The pediatricians therefore initiated a redesign of available content to reflect current guidelines by actively prompting clinicians. The project team, comprised of two community health center (CHC) pediatricians and two tertiary care center pediatricians, continues conducting this work with the assistance of the informatics and research team at the CHC network that hosts the EHR.

METHODS

Setting

Erie Family Health Center (Erie) is a federally qualified health center in Chicago that has ≥30,000 active, unduplicated patients seen yearly for ≥130,000 medical and dental visits at nine clinical sites. Over 60 clinicians from different disciplines provide primary care for children and adolescents. A recent medical record review at Erie showed that 46% of the 2–17 year-old patients meet national definitions of overweight (≥85th to <95th BMI percentile for age/gender on Center for Disease Control growth charts) or obesity (≥95th BMI percentile).

In 2006, Erie implemented a robust, commercially available EHR that is hosted centrally by a large CHC network called the Alliance of Chicago Community Health Services (Alliance). The Alliance-wide EHR collects and analyzes data at both patient and population levels to improve outcomes. This network approach includes evidence-based, point of care clinical decision support, integrated performance measures, and a data warehouse for robust data analyses.

CDSS development

The team sought to revise the content of existing visit templates to more effectively prompt identification and management of overweight/obesity and its comorbidities. Previously, the EHR at Erie calculated body mass index (BMI), and BMI percentile, but once a child was identified as overweight/obese, clinicians had no guidance on “best practices” for management. Guidelines identified included the 2007 American Academy of Pediatrics Expert Committee Guidelines; 2004 National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) guidelines on diagnosis and treatment of high blood pressure in children; 1992 National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Report, and, when they became available, draft guidelines of the 2006 NHLBI panel on recommendations for CV risk reduction [11, 12]. Most of these guidelines focus on evaluating for obesity (by regular evaluation of BMI), identifying obesity risk factors, and managing comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension, fatty liver disease, and dyslipidemia [13–16]

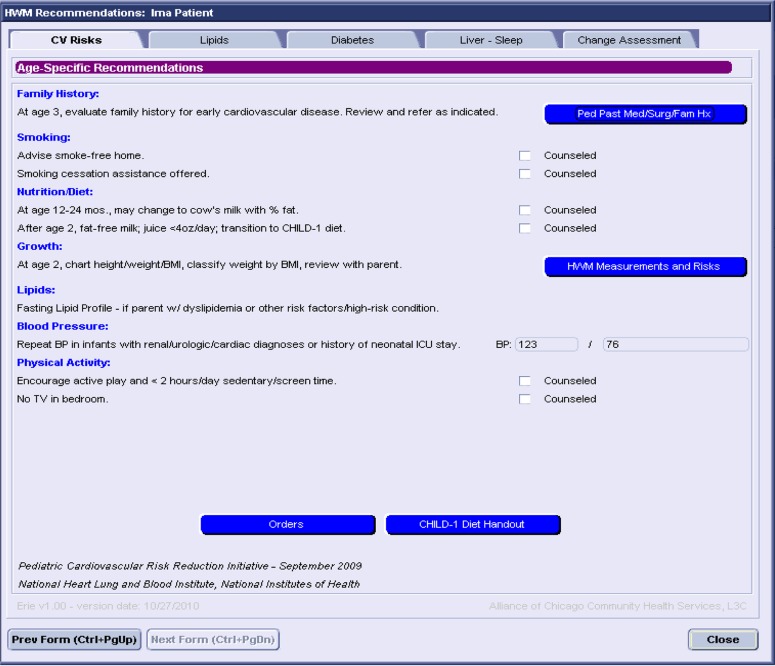

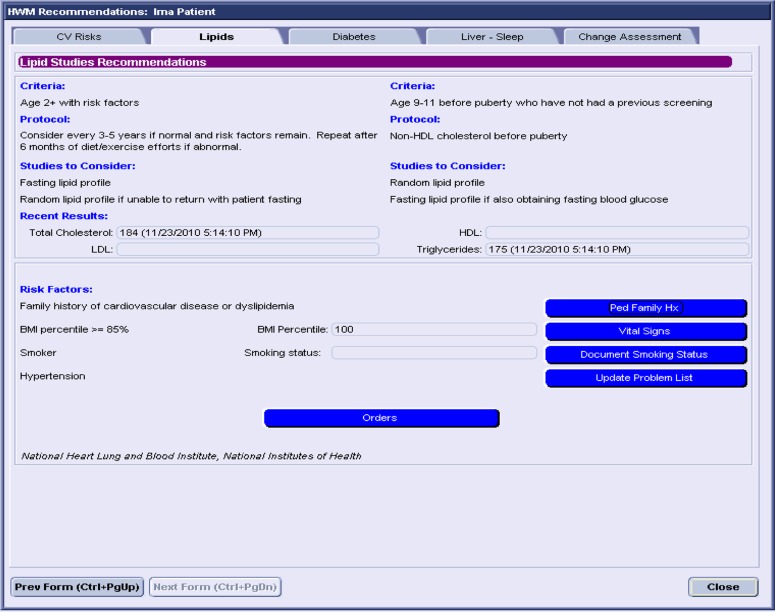

Fifteen Erie clinicians followed a consensus process to arrive at a desired customized content for the CDSS. Individuals were assigned to review and summarize relevant literature. Group members then discussed the information and agreed on specific protocols to imbed in the EHR. Members of the research team from the Alliance incorporated content into EHR end user templates (see Figs. 1 and 2). This involved programming the system to support EHR-facilitated interpretation of patient data such as nutritional status categories (i.e., normal weight, overweight, and obese) according to BMI percentile, identification of abnormal blood pressure values (based on height percentile/age/gender), customized order templates driven by the selected guidelines, and prompts for adding relevant family, medical, and social history, and the inclusion of relevant diagnoses to the active problem list. For example, an obese 11-year-old patient whose mother has type II diabetes would be flagged to receive a fasting glucose test. Additionally, the screens include fields to document assessment/counseling of diet, sleep, exercise habits, and screen time and assessment of patient/family readiness to make change. Up to three patient goals for change can now be documented, and progress toward previously documented goals can be assessed. The clinical team met frequently with the programming team to edit the screens so they were meaningful to clinicians while still being feasibly incorporated into the larger visit template.

Fig 1.

Screen shot of electronic decision support template for age-specific recommendations

Fig 2.

Screen shot of electronic decision support template for recommended lipid studies

Evaluation

The evaluation was designed as a pre/post analysis using two evaluation components. One component is a clinician survey that assesses knowledge, self-reported efficacy, and satisfaction with the EHR. This survey was conducted before the implementation of the new CDSS and will be repeated 4–6 months after its implementation. The second component is the frequency of appropriate documentation of identification and management of overweight/obesity in the chart. Impact of the intervention on care will be determined by change in frequency of identification, documentation, and management of overweight/obese children (Table 1). These indicators will be assessed by EHR query at baseline, and again 4–6 months after the customized healthy weight management forms have been in use.

Table 1.

Indicators for the pre/post assessment of provider behavior related to introduction of evidence-based content in the electronic health record system at Erie Family Health Center

| Indicators (pre/post) | Data collection method |

|---|---|

| •% of 2–18-year-olds seen for well child care with BMI 85–94th percentile or >95th percentile | EHR query |

| • Correct identification of BMI classification on problem list (BMI 5th–84th percentile, BMI 85–94th percentile, BMI >95th percentile) | EHR query |

| • Compliance with diabetes screening recommendations | EHR query |

| •% of patients with documentation of comorbidities on problem list (elevated blood pressure, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, hypercholesterolemia, etc.) | EHR query |

| • Pre- vs. post-intervention clinician knowledge of guidelines (survey) | Survey |

| • Pre- vs. post-intervention clinician satisfaction with EMR system/support | Survey |

| • Pre- vs. post-intervention clinician reported “self-efficacy” for identifying/managing pediatric overweight/obesity | Survey |

| • Change in BMI among patients where forms used/guidelines followed (Alliance question) | EHR query |

RESULTS: PROGRESS TO DATE

The CDSS conceptualization and implementation took longer than anticipated (18 months), and the project timeline has been extended for 6 months. The electronic CDSS module was recently implemented, prior to which, a 2-hour training session was attended by Erie providers. The session included a detailed presentation of the CDSS, use instructions, information on the optional use of sections within the module, and prompted feedback. The implementation phase will last approximately 4 months, after which the team will conduct post-implementation evaluations and troubleshoot any problems with the system.

Anecdotally, while clinicians are still learning to use the new content, they appreciate that the CDSS screens prompt ordering of recommended screening tests and can longitudinally document patient/family selected goals and readiness for change. Clinicians suggest that, in the future, additional data could be obtained by patient/family survey before the visit starts.

DISCUSSION AND LESSONS LEARNED

Although the project is still ongoing, there have been several lessons learned to date:

When a clinical topic is deemed of high importance by clinicians, they are eager to contribute to work on changing care systems such as redesign of EHR content. Erie’s pediatric group has had goals for improving care of overweight/obese children in the CHC health care plan for years, and all pediatric providers enthusiastically agreed to this project.

It is critical to find a balance between addressing all important recommendations while not increasing the burden of data collection.

The time from conceptualizing to implementation of health information technology-based interventions is longer than expected. It will take us 24 months instead of the originally planned 18 to finish the project. Delays were both on the information side (the 2006 committee on CV risk reduction has still not released final recommendations a year after they were expected) and on the technology/programming side.

Our next steps are to analyze findings from the evaluation by the end of 2011, then seek funding to further study and improve evidence-based clinician practice around pediatric CV risk reduction, leveraging informatics and input from practicing community clinicians. From this pilot, it is clear that commercially available EHR products do not automatically come with comprehensive functionality to support evidence-based interventions around clinician behavior. Customized modifications to the EHR are needed to achieve the full promise of health information technology as it relates to delivering high quality, patient-centered, for underserved populations.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study is being funded through a seed grant from Northwestern University’s Clinical and Translational Sciences Award.

Conflicts of interest

None of the authors have potential conflicts of interest or corporate sponsors.

Footnotes

Implications

Practice: Having patient-tailored, actionable information at the point of care promotes correct identification of weight classification and influences clinician behavior by guiding evidence-based management.

Policy: Incentives and resources should be directed at alignment around guidelines and performance measures related to healthy weight management.

Research: Further research is needed to determine which types of decision support and presentations of electronic health record content are most influential on clinician behavior. Further studies should also evaluate influences on patient behavior.

Contributor Information

Sara M Naureckas, Phone: +1-312-6663494, FAX: +1-312-6665867, Email: snaureckas@eriefamilyhealth.org.

Erin O’Brien Kaleba, Email: ekaleba@alliancechicago.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Garg AX, Adhikari NJ, McDonald H, Rosas-Arellano MP, Devereaux PJ, Beyene J, Sam J, Haynes RB. Effects of computerized decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes. JAMA. 2005;293(10):1223–1238. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.10.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, Lobach DF. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. BMJ. 2005;330(7494):765. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38398.500764.8F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dexheimer JW, Talbot TR, Sanders DL, Rosenbloom ST, Aronsky D. Prompting clinician about preventative care measures: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2008;15(3):31–320. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daley MF, Steiner JF, Kempe A, Beaty BL, Pearson KA, Jones JS, Lowery NE, Berman S. Quality improvement in immunization delivery following an unsuccessful immunization recall. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2004;4:217–233. doi: 10.1367/A03-176R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaw JS, Samuels RC, Larusso EM, Bernstein HH. Impact of an encounter-based prompting system on resident vaccine administration performance and immunization knowledge. Pediatrics. 2000;105:978–983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee NJ, Chen ES, Currie LM, Donovan M, Hall EK, Jia H, John RM, Bakken S. The effect of a mobile clinical decision support system on the diagnosis of obesity and overweight in acute and primary care encounters. Advances in Nursing Science. 2009;32(3):211–221. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0b013e3181b0d6bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee NJ, Bakken S. Development of a prototype personal digital assistant-decision support system for the management of adult obesity. International Journalof Medical Informatics. 2007;76S:S281–S292. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rattay KT, Ramakrishnan M, Atkinson A, Gilson M, Drayton V. Use of an electronic medical record system to support primary care recommendations to prevent, identify, and manage childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2009;123:S100–S107. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1755J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perrin EM, Flower KB, Garrett J, Ammerman AS. Preventing and treating obesity: pediatrician’s self-efficacy, barriers, resources, and advocacy. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2005;5(3):150–6. doi: 10.1367/A04-104R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perrin EM, Vann JC, Lazorick S, Ammerman A, Teplin S, Flower K, Wegner SE, Benjamin JT. Bolstering confidence in obesity prevention and treatment counseling for resident and community pediatricians. Patient Educational Counselling. 2008;73(2):179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Appendix: Expert committee recommendations on the assessment, prevention, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity (2007). Available at: http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/433/ped_obesity_recs.pdf. Accesssed 20 June 2007.

- 12.Barlow SE. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120:S164–S192. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barlow SE, Dietz WH (1998) Obesity evaluation and treatment: expert committee recommendations. Pediatrics. Available at http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/102/3/e29 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition Prevention of pediatric overweight and obesity. Pediatrics. 2003;112:424–430. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.2.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Diabetes Association Type 2 diabetes in children and adolescents (consensus statement) Diabetes Care. 2000;23:381–389. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.3.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daniels SR, Greer FR. Lipid screening and cardiovascular health in childhood. Pediatrics. 2008;122:198–208. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]