Abstract

Objectives

We measured the prevalence and incidence of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in young female subjects recruited for a safety and immunogenicity trial of the bivalent HPV-16/18 vaccine in Tanzania.

Methods

Healthy HIV negative female subjects aged 10–25 years were enrolled and randomised (2:1) to receive HPV-16/18 vaccine or placebo (Al(OH)3 control). At enrolment, if sexually active, genital specimens were collected for HPV DNA, other reproductive tract infections and cervical cytology. Subjects were followed to 12 months when HPV testing was repeated.

Results

In total 334 participants were enrolled; 221 and 113 in vaccine and control arms, respectively. At enrolment, 74% of 142 sexually active subjects had HPV infection of whom 69% had >1 genotype. Prevalent infections were HPV-45 (16%), HPV-53 (14%), HPV-16 (13%) and HPV-58 (13%). Only age was associated with prevalent HPV infection at enrolment. Among 23 girls who reported age at first sex as 1 year younger than their current age, 15 (65.2%) had HPV infection. Of 187 genotype-specific infections at enrolment, 51 (27%) were present at 12 months. Overall, 67% of 97 sexually active participants with results at enrolment and 12 months had a new HPV genotype at follow-up. Among HPV uninfected female subjects at enrolment, the incidence of any HPV infection was 76 per 100 person-years.

Conclusions

Among young women in Tanzania, HPV is highly prevalent and acquired soon after sexual debut. Early HPV vaccination is highly recommended in this population.

Keywords: HPV, AFRICA, SEROPREVALENCE

Introduction

The primary cause of cervical cancer is persistent infection with high risk (HR) human papillomavirus (HPV) genotypes. East Africa has one of the highest rates of cervical cancer in the world.1 Reviews of global age-specific prevalence show a high prevalence of HPV in young sexually active women,2–4 but there are few data on the epidemiology of HPV infection in sexually active girls and young women aged <25 years in East Africa, where prevalences have been reported as high as 55% in Mozambique.3 We measured the burden of HPV infection and risk factors for infection in a cohort of HIV negative girls and young women aged 10–25 years in Tanzania recruited for a safety and immunogenicity trial of a prophylactic HPV vaccine.5 These data will be used to help to inform recommended age of HPV vaccination in a future national vaccination programme.

Methods

Study design

This substudy was nested within a Phase IIIb immunogenicity and safety study of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine. This double-blind, randomised, controlled trial (NCT00481767) was conducted in Dakar, Senegal and Mwanza, Tanzania, with eligible female subjects being randomly assigned (2:1) to receive either three doses of vaccine (vaccine group) or Al(OH)3 (control group).6 Trial results have been published elsewhere.6 The HPV substudy was conducted between October 2007 and July 2010 in Mwanza.6 The trial and the substudy were approved by the ethics committees of the National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR), Tanzania and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

Study participants

Study participants were recruited from schools, colleges and family planning clinics in Mwanza and invited to attend an eligibility screening visit 1 month before enrolment. They were eligible if they were aged 10–25 years, HIV negative, not pregnant, had ≤6 lifetime sexual partners, were free of health problems, had no history of neurological disorders and, if sexually active, were willing to use contraception or abstain from sex for 30 days before vaccination until 2 months after completion of vaccination. This was requested for all participants and contraception was provided at the research clinic (the majority (75%) of sexually active women used hormonal contraception throughout the study). Participants were asked for written consent or, if illiterate, for witnessed thumb-printed informed consent. Parental/guardian consent was obtained for participants aged below 18 years.

Follow-up procedures

Participants were followed to month 12. HPV vaccine (Cervarix, GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, Rixensart, Belgium) or the control injection was given at months 0, 1 and 6.

Specimen collection

Blood samples were collected at the screening visit (day 30) for HIV and syphilis. At enrolment (month 0), before vaccination, participants were interviewed about sexual activity and, if sexually active, symptoms of reproductive tract infections. A genital examination was performed on participants who reported ever being sexually active. Vaginal swabs were taken for bacterial vaginosis (BV) and Trichomonas vaginalis (TV). A Papanicolou smear was taken and an endocervical swab was collected for Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG) and Chlamydia trachomatis (CT). An ectocervical swab and endocervical swab were also taken for HPV DNA testing at enrolment and month 12 from participants who reported ever being sexually active. Syndromic reproductive tract infection treatment was provided and treatment was offered for NG, CT, TV and symptomatic BV diagnosed on laboratory testing.

Laboratory tests

Cervical swabs for HPV DNA testing were frozen at −20°C and sent to the Catalan Institute of Oncology in Barcelona where they were genotyped for 37 different HPV genotypes by the Roche Linear Array assay (Roche, Branchburg, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The PCR reaction included an additional primer pair targeting the human β-globin gene as an internal control. Genotyping was performed in an automated system, Auto-LiPA 48 (Tecan Austria GmbH, distributed by Innogenetics). HPV-16, -18, -31, -33, -35, -39, -45, -51, -52, -56, -58, -59 and -68 were considered HR genotypes; all other genotypes were considered low risk (LR).7

Papanicolou smears were processed and results recorded from a single reading in Mwanza. Endocervical swabs were tested for NG and CT by PCR (AMPLICOR, Roche, Branchburg, USA) in Mwanza. Gram stained vaginal smears were examined for Candida albicans spores and for BV using the Nugent score while TV was diagnosed by culture (InPouch TV, BioMed Diagnostics, San Jose, California, USA).

HIV serology was determined using two rapid tests, Determine HIV-1/2 (Alere Medical Co., Matsudo-shi, Chiba, Japan) and SD Bioline HIV-1/2 3.0 (SD Standard Diagnostics, Inc. Hagal-dong, Kyonggi-do, Korea). Positive, indeterminate or discordant results were confirmed by an HIV Ag–Ab combination ELISA (Murex Biotech, Dartford, UK) and Uni-Form II Ag–Ab micro ELISA (bioMérieux, Basingstoke, UK). Discordant samples on ELISA were tested for P24 antigen (Biorad, Genetic Systems, UK). Serum samples were tested for syphilis by the rapid plasma reagin test (Immutrep, Omega Diagnostics, Alva, UK) and Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay (Fujirebio, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis

Data were double entered and verified in DMSys (SigmaSoft International), and analysed using STATA V.11.0 (StataCorp LP; College Station, Texas, USA).

The trial aimed to enrol 333 participants in Mwanza (222 and 111 participants in the vaccine and control arms, respectively). Enrolment was age-stratified, with a third of participants in the 15–25 years age-stratum and the remainder in the 10–14 years age-stratum.

Cohort characteristics at enrolment were tabulated and HPV genotype prevalence was calculated among sexually active participants. The number of new infections (genotype not present at enrolment, present at month 12), persistent infections (same genotype at enrolment and month 12) and cleared infections (positive for the genotype at enrolment but negative for that genotype at month 12) were tabulated by treatment arm and overall. Type-specific persistence and clearance were calculated among women who were infected with the genotype at enrolment. Type-specific cumulative incidence was calculated among those who were negative for the genotype at enrolment. The proportion of women with any new HPV infection, any persistence and any clearance were calculated among all women who had samples at both time points.

The incidence rate (per 100 person-years) of any HPV genotype, and any HR genotype, was calculated among women who were negative for all genotypes, or negative for all HR genotypes, respectively, at enrolment. Person-years at risk were calculated from date of enrolment until date of HPV acquisition, assumed to occur mid-way between the last negative and first positive results.

Risk factors associated with prevalent HPV infection at enrolment among sexually active participants were analysed using logistic regression to estimate OR and 95% CI. Participants who were positive for any HPV genotype were classed as ‘infected’; those negative for all HPV genotypes were classed as ‘uninfected’. Age was considered an a priori confounder, and so was included in all models. Factors that were associated with HPV infection at p<0.20 in the age-adjusted analysis were considered for inclusion in a multivariable model; those remaining independently associated at p<0.10 were retained. After age-adjustment, no other variables were associated with HPV infection at p<0.10, and so no further model building was done.

Results

Cohort screening, enrolment and follow-up

In total, 587 participants attended the screening visit. Of 379 eligible female subjects, 334 (88.1%) were enrolled (221 and 113 in the vaccine and control arms, respectively); 45 refused, 15 had moved away, 16 did not attend the visit and 25 were not enrolled because the enrolment target had been reached. The median age of enrolled participants was 18 years (IQR 13–19).

Overall, 308/334 (92.2%) participants attended the month 12 visit; 206 (93.2%) in the vaccine arm and 102 (90.3%) in the placebo arm (p=0.34).

Reasons for not completing follow-up included withdrawal of consent (10), moved away (4), temporary travel (5), being untraceable (3) and unknown reason (4).

Cohort description at enrolment

Approximately half (46.5%) of 334 enrolled participants had secondary school or higher education; 78.2% were currently students. Most (87.4%) were single. Only 2 (0.6%) had ever smoked and 4 (1.3%) had vulval genital warts. No cervico-vaginal warts were observed.

At enrolment, 142 (42.5%) participants reported having passed their sexual debut; median reported age at first sex was 16 years (IQR 15–17), and 75 (52.8%) reported >1 lifetime sexual partner. Two-thirds (66.0%) of sexually active women reported never using condoms. Cervical and vaginal samples were available for 117 (82.4%) and 125 (88.0%) participants, respectively. One participant had congenital absence of a cervix and samples for NG, CT and HPV were taken from the vaginal vault. There were no cases of low or high grade squamous intraepithelial lesions on cervical cytology. Overall 27.4% had BV, 12.8% had TV, 5.1% had CT and 2.6% had NG. Two participants (1.4%) had active syphilis.

Prevalence of HPV at enrolment by genotype, age and recent sexual debut

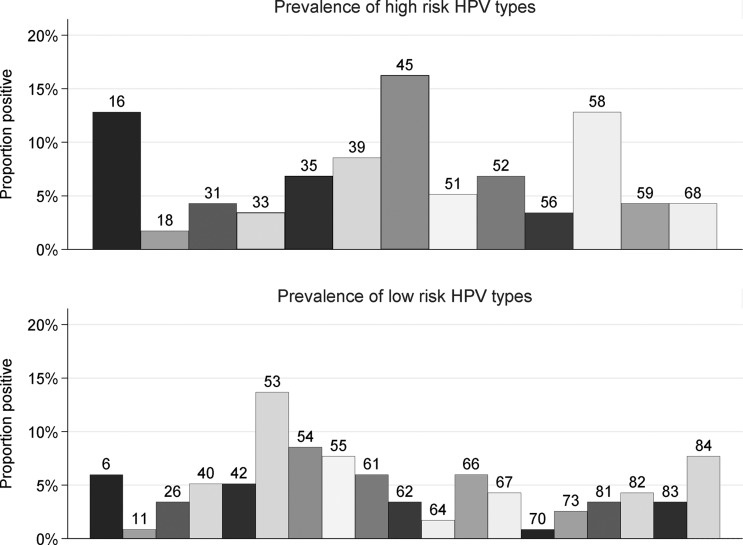

Overall 73.5% (86/117; 95% CI 64.5 to 81.2) of sexually active participants with HPV results at enrolment had HPV infection (table 1). Assuming that girls who had not had sex were HPV negative, the overall cohort HPV prevalence was 27.8% (86/309). In total, 54.7% (64/117) of sexually active participants were infected with HR genotypes. The most common (figure 1) were HPV-45 (16.2%), HPV-16 (12.8%) and HPV-58 (12.8%). Seventeen participants (14.5%) were infected with either HPV-16 or -18. The most common LR genotype was HPV-53 (13.7%).

Table 1.

HPV prevalence at enrolment and at 12 months among sexually active subjects

| Enrolment | 12 months | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control n (%) |

Vaccine n (%) |

Total n (%) |

Control n (%) |

Vaccine n (%) |

Total n (%) |

|

| Swab results available/sexually active | 33/47 (70.2) | 84/95 (88.4) | 117/142 (82.4) | 37/45 (82.2) | 85/91 (93.4) | 122/136 (89.7) |

| Any HPV type | ||||||

| Yes | 25 (75.8) | 61 (72.6) | 86 (73.5) | 25 (67.6) | 66 (77.6) | 91 (74.6) |

| Any high risk HPV | ||||||

| Yes | 18 (54.5) | 46 (54.8) | 64 (54.7) | 12 (32.4) | 50 (58.8) | 62 (50.8) |

| HPV 16/18 | ||||||

| Yes | 4 (12.1) | 13 (15.5) | 17 (14.5) | 3 (8.1) | 5 (5.9) | 8 (6.6) |

| Number of HPV genotypes | ||||||

| None | 8 (24.2) | 23 (27.4) | 31 (26.5) | 12 (32.4) | 19 (22.4) | 31 (25.4) |

| 1 | 7 (21.2) | 20 (23.8) | 27 (23.1) | 11 (29.7) | 18 (21.2) | 29 (23.8) |

| 2 | 9 (27.3) | 16 (19.0) | 25 (21.4) | 2 (5.4) | 19 (22.4) | 21 (17.2) |

| 3 | 4 (12.1) | 11 (13.1) | 15 (12.8) | 4 (10.8) | 14 (16.5) | 18 (14.8) |

| 4 or more | 5 (15.2) | 14 (16.7) | 19 (16.2) | 8 (21.6) | 15 (17.6) | 23 (18.9) |

| Swab results available at both visits/sexually active at both visits | 24/39 (61.5) | 73/84 (86.9) | 97/123 (78.9) | |||

| Any new HPV type | ||||||

| Yes | 16 (66.7) | 49 (67.1) | 65 (67.0) | |||

| Any new high risk HPV | ||||||

| Yes | 7 (29.2) | 34 (46.6) | 41 (42.3) | |||

| Any new HPV-16/18 | ||||||

| Yes | 2 (8.3) | 1 (1.4) | 3 (3.1) | |||

| Any persistent HPV | ||||||

| Yes | 10 (41.7) | 22 (30.1) | 32 (33.0) | |||

| Any persistent high risk HPV | ||||||

| Yes | 5 (20.8) | 16 (21.9) | 21 (21.6) | |||

HPV, human papillomavirus.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of human papillomavirus (HPV) by genotype in 117 sexually active girls at enrolment.

In sexually active female subjects, HPV prevalence was 36% (4/11) in those aged ≤16 years, increased to 86% (18/21) in 19–20-year-olds, then declined to 64% (18/28) in those aged ≥23 years (table 2). Assuming that female subjects who were not sexually active were HPV negative, cohort HPV prevalence was 3% in those aged ≤16 years, then showed a similar trend of rapid increase with age, followed by a gradual decline (see online supplementary figure S1).

Table 2.

Cervical HPV infection at enrolment and associated factors among 117 sexually active subjects

| No with HPV/number sexually active (%) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Age-adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic factors | |||

| Age group (years) | p=0.02 | p=0.02 | |

| ≤16 | 4/11 (36.4) | 0.13 (0.03 to 0.60) | 0.13 (0.03 to 0.60) |

| 17–18 | 26/32 (81.2) | 1 | 1 |

| 19–20 | 18/21 (85.7) | 1.38 (0.31 to 6.27) | 1.38 (0.31 to 6.27) |

| 21–22 | 20/25 (80.0) | 0.92 (0.25 to 3.46) | 0.92 (0.25 to 3.46) |

| 23+ | 18/28 (64.3) | 0.42 (0.13 to 1.35) | 0.42 (0.13 to 1.35) |

| Religion | p=0.97 | p=0.66 | |

| Catholic | 36/49 (73.5) | 1 | 1 |

| Other Christian | 26/ 36 (72.2) | 0.94 (0.36 to 2.47) | 0.84 (0.29 to 2.42) |

| Muslim | 24/32 (75.0) | 1.08 (0.39 to 3.01) | 1.47 (0.49 to 4.45) |

| Education level | p=0.72 | p=0.78 | |

| Less than primary | 11/14 (78.6) | 1 | 1 |

| Primary | 32/46 (69.6) | 0.62 (0.15 to 2.59) | 0.59 (0.13 to 2.73) |

| Secondary or above | 43/57 (75.4) | 0.84 (0.20 to 3.44) | 0.64 (0.13 to 3.10) |

| Marital status | p=0.51 | p=0.31 | |

| Single | 57/76 (75.0) | 1 | 1 |

| Married | 27/39 (69.2) | 0.75 (0.32 to 1.76) | 0.66 (0.20 to 2.16) |

| Separated/divorced | 2/2 (100) | – | – |

| Number of children ever had | p=0.76 | p=0.63 | |

| None | 45/62 (72.6) | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 22/31 (71.0) | 0.92 (0.36 to 2.40) | 0.71 (0.22 to 2.32) |

| 2 or more | 19/24 (79.2) | 1.44 (0.46 to 4.45) | 1.32 (0.32 to 5.41) |

| Behavioural factors | |||

| Lifetime partners | p=0.82 | p=0.70 | |

| 1 | 35/47 (74.5) | 1 | 1 |

| 2–3 | 36/48 (75.0) | 1.03 (0.41 to 2.60) | 0.76 (0.27 to 2.17) |

| 4–5 | 15/22 (68.2) | 0.73 (0.24 to 2.23) | 0.59 (0.17 to 2.07) |

| Age at first sex (years) | p=0.19 | p=0.53 | |

| ≤14 | 10/17 (58.8) | 1 | 1 |

| 15–16 | 35/48 (72.9) | 1.88 (0.59 to 5.99) | 1.53 (0.41 to 5.71) |

| 17–18 | 31/37 (83.8) | 3.73 (1.02 to 13.72) | 2.66 (0.58 to 12.20) |

| 19+ | 9/14 (64.3) | 1.26 (0.29 to 5.42) | 1.18 (0.20 to 6.97) |

| Time since first sex (years) | p=0.40 | p=0.74 | |

| ≤1 year | 19/29 (65.5) | 1 | 1 |

| 2–3 years | 26/34 (76.5) | 1.71 (0.57 to 5.15) | 1.29 (0.38 to 4.41) |

| 4–5 years | 21/25 (84.0) | 2.76 (0.74 to 10.29) | 2.23 (0.49 to 10.17) |

| >5 years | 20/29 (69.0) | 1.17 (0.39 to 3.51) | 1.27 (0.28 to 5.81) |

| Condom use | p=0.05 | p=0.11 | |

| Never | 53/79 (67.1) | 1 | 1 |

| Sometimes | 11/12 (91.7) | 5.40 (0.66 to 44.08) | 4.69 (0.54 to 40.51) |

| Often/always | 22/26 (84.6) | 2.70 (0.84 to 8.64) | 2.64 (0.76 to 9.16) |

| Using hormonal contraception at screening | p=0.08 | p=0.17 | |

| No | 52/76 (68.4) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 34/41 (82.9) | 2.24 (0.87 to 5.78) | 2.07 (0.71 to 5.97) |

| Clinical factors | |||

| Ectopy | p=0.45 | p=0.33 | |

| None | 64/89 (71.9) | 1 | 1 |

| <20% | 19/23 (82.6) | 1.86 (0.57 to 6.00) | 2.17 (0.63 to 7.52) |

| 20%–50% | 3/5 (60.0) | 0.59 (0.09 to 3.72) | 0.53 (0.08 to 3.75) |

| Age at menarche (years) | p=0.21 | p=0.29 | |

| ≤13 | 14/24 (58.3) | 1 | 1 |

| 14 | 22/31 (71.0) | 1.75 (0.57 to 5.36) | 1.38 (0.41 to 4.70) |

| 15 | 23/29 (79.3) | 2.74 (0.82 to 9.19) | 2.86 (0.77 to 10.59) |

| 16+ | 27/33 (81.8) | 3.21 (0.97 to 10.68) | 2.78 (0.74 to 10.48) |

| Vaginal flora | p=0.64 | p=0.88 | |

| Negative | 50/65 (76.9) | 1 | 1 |

| Positive (BV) | 22/32 (68.8) | 0.66 (0.26 to 1.70) | 0.83 (0.30 to 2.30) |

| Intermediate | 14/20 (70.0) | 0.70 (0.23 to 2.14) | 0.75 (0.23 to 2.46) |

| Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhoeae | p=0.92 | p=0.52 | |

| Negative | 80/109 (73.4) | 1 | 1 |

| Positive | 6/8 (75.0) | 1.09 (0.21 to 5.70) | 1.80 (0.28 to 11.37) |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | p=0.22 | p=0.76 | |

| Negative | 77/102 (75.5) | 1 | 1 |

| Positive | 9/15 (60.0) | 0.49 (0.16 to 1.50) | 0.82 (0.22 to 2.97) |

| Syphilis serology* | |||

| Negative | 84/114 (73.7) | ||

| Past infection | 0/1 (–) | – | – |

| Active infection | 2/2 (100) | – | – |

*Negative defined as negative on both TPPA and RPR. Past infection defined as positive on TPPA and negative on RPR. Active infection defined as positive on both TPPA and RPR.

BV, bacterial vaginosis; HPV, human papillomavirus; RPR, rapid plasma reagin; TPPA, Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay.

Among HPV infected participants, 68.6% (59/86) were infected with >1 genotype.

Of six participants who reported age at sexual debut as their current age, 4 (66.6%) were HPV infected. Among 23 girls who reported age at first sex as 1 year younger than their current age, 15 (65.2%) had HPV infection.

Factors associated with prevalent HPV infection at enrolment

In the unadjusted analysis (table 2), HPV prevalence was higher among participants who reported sometimes or often using condoms than among those who reported never using condoms (p=0.05). There was some evidence that HPV prevalence was higher among participants using hormonal contraception (combined oral contraceptives, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate or implants) at screening (p=0.08). There was no evidence of an association with lifetime partners, age at first sex or marital status, education, religion, parity and other STIs.

In the adjusted analysis, only age remained significantly associated with HPV infection at p<0.10. Compared with participants aged 17–18 years, those aged <17 years had lower odds of HPV infection (adjusted OR 0.19, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.90). The odds of infection were also lower in female subjects aged 23 years and above (adjusted OR 0.55, 95% CI 0.16 to 1.90). There was weak evidence of an association with reported condom use after adjusting for age (p=0.11).

Incidence, persistence and clearance of HPV infection over 12 months

At month 12, 136/308 (44.3%) participants reported being sexually active. In all, 13 reported becoming sexually active during follow-up, of whom 9 (69.2%) were HPV-infected at 12 months, and five had HR genotypes. Overall, HPV prevalence at 12 months was 74.6% (9/122 sexually participants with HPV results; 95% CI 65.9 to 82.0; table 1).

Of 187 genotype-specific infections at enrolment, 51 (27.2%) were present at month 12; persistence was similar for HR and LR genotypes (table 3). HR genotype persistence was 30.4% (7/23) and 27.0% (17/63) in the control and vaccine arms, respectively (p=0.75). LR genotype persistent infections were non-significantly higher in the control (36.4%, 12/33) compared with the vaccine arm (22.1%, 15/68; p=0.13). Overall, 33.9% (19/56) and 24.4% (32/131) of all infections were still present at month 12 in the control and vaccine arms, respectively (p=0.18).

Table 3.

Cumulative HPV incidence over 1 year, persistence and clearance among 97 women with results available at enrolment and 12 months, by HPV genotype

| Control (N=24 women) | Vaccine (N=73 women) | Total (N=97 women) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infected at visit 1 | Persistent* | Cleared* | New† | Infected at visit 1 | Persistent* | Cleared* | New† | Infected at visit 1 | Persistent* | Cleared* | New† | |

| High risk | ||||||||||||

| HPV-16 | 3 | – | 3 (100%) | 1 (4.8%) | 11 | 4 (36.4%) | 7 (63.6%) | 0 (–) | 14 | 4 (28.6%) | 10 (71.4%) | 1 (1.2%) |

| HPV-18 | 1 | – | 1 (100%) | 1 (4.4%) | 0 | – | – | 1 (1.4%) | 1 | – | 1 (100%) | 2 (2.1%) |

| HPV-31 | 0 | – | – | 0 (–) | 3 | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (66.7%) | 3 (4.3%) | 3 | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (66.7%) | 3 (3.2%) |

| HPV-33 | 1 | – | 1 (100%) | 0 (–) | 2 | 1 (50.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 2 (2.8%) | 3 | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (66.7%) | 2 (2.1%) |

| HPV-35 | 1 | 1 (100%) | – | 0 (–) | 4 | 2 (50.0%) | 2 (50.0%) | 6 (8.7%) | 5 | 3 (60.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | 6 (6.5%) |

| HPV-39 | 1 | – | 1 (100%) | 1 (4.4%) | 7 | 1 (14.3%) | 6 (85.7%) | 8 (12.1%) | 8 | 1 (12.5%) | 7 (87.5%) | 9 (10.1%) |

| HPV-45 | 4 | – | 4 (100%) | 0 (–) | 13 | 1 (7.7%) | 12 (92.3%) | 3 (5.0%) | 17 | 1 (5.9%) | 16 (94.1%) | 3 (3.8%) |

| HPV-51 | 2 | 1 (50.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 2 (9.1%) | 3 | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (66.7%) | 9 (12.9%) | 5 | 2 (40.0%) | 3 (60.0%) | 11 (12.0%) |

| HPV-52 | 1 | 1 (100%) | – | 1 (4.4%) | 7 | 2 (28.6%) | 5 (71.4%) | 4 (6.1%) | 8 | 3 (37.5%) | 5 (62.5%) | 5 (5.6%) |

| HPV-56 | 2 | – | 2 (100%) | 1 (4.6%) | 0 | – | – | 3 (4.1%) | 2 | – | 2 (100%) | 4 (4.2%) |

| HPV-58 | 3 | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (4.8%) | 9 | 3 (33.3%) | 6 (66.7%) | 0 (–) | 12 | 4 (33.3%) | 8 (66.7%) | 1 (1.2%) |

| HPV-59 | 2 | 1 (50.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 0 (–) | 2 | – | 2 (100%) | 3 (4.2%) | 4 | 1 (25.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | 3 (3.2%) |

| HPV-68 | 2 | 2 (100%) | – | 1 (4.6%) | 2 | 1 (50.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 6 (8.5%) | 4 | 3 (75.0%) | 1 (25.0%) | 7 (7.5%) |

| All high risk infections‡ | 23 | 7 (30.4%) | 16 (69.6%) | 9 | 63 | 17 (27.0%) | 46 (73.0%) | 48 | 86 | 24 (27.9%) | 62 (72.1%) | 57 |

| Low risk | ||||||||||||

| HPV-6 | 2 | – | 2 (100%) | 3 (13.6%) | 4 | 1 (25.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | 3 (4.4%) | 6 | 1 (16.7%) | 5 (83.3%) | 6 (6.6%) |

| HPV-11 | 0 | – | – | 0 (–) | 1 | – | 1 (100%) | 4 (5.6%) | 1 | – | 1 (100%) | 4 (4.2%) |

| HPV-26 | 1 | – | 1 (100%) | 1 (4.4%) | 3 | – | 3 (100%) | 2 (2.9%) | 4 | – | 4 (100%) | 3 (3.2%) |

| HPV-40 | 2 | – | 2 (100%) | 1 (4.6%) | 3 | – | 3 (100%) | 2 (2.9%) | 5 | – | 5 (100%) | 3 (3.3%) |

| HPV-42 | 1 | – | 1 (100%) | 0 (–) | 4 | 1 (25.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | 3 (4.4%) | 5 | 1 (20.0%) | 4 (80.0%) | 3 (3.3%) |

| HPV-53 | 1 | 1 (100%) | – | 5 (21.7%) | 10 | 2 (20.0%) | 8 (80.0%) | 4 (6.4%) | 11 | 3 (27.3%) | 8 (72.7%) | 9 (10.5%) |

| HPV-54 | 5 | 3 (60.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | 2 (10.5%) | 3 | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (66.7%) | 4 (5.7%) | 8 | 4 (50.0%) | 4 (50.0%) | 6 (6.7%) |

| HPV-55 | 2 | 1 (50.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 1 (4.6%) | 6 | 1 (16.7%) | 5 (83.3%) | 2 (3.0%) | 8 | 2 (25.0%) | 6 (75.0%) | 3 (3.4%) |

| HPV-61 | 2 | 1 (50.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 2 (9.1%) | 5 | 2 (40.0%) | 3 (60.0%) | 5 (7.4%) | 7 | 3 (42.9%) | 4 (57.1%) | 7 (7.8%) |

| HPV-62 | 0 | – | – | 1 (4.2%) | 4 | 2 (50.0%) | 2 (50.0%) | 3 (4.4%) | 4 | 2 (50.0%) | 2 (50.0%) | 4 (4.3%) |

| HPV-64 | 0 | – | – | 0 (–) | 1 | – | 1 (100%) | 2 (2.8%) | 1 | – | 1 (100%) | 2 (2.1%) |

| HPV-66 | 3 | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (4.5%) | 4 | – | 4 (100%) | 6 (8.7%) | 7 | 2 (28.6%) | 5 (71.4%) | 7 (7.8%) |

| HPV-67 | 2 | – | 2 (100%) | 1 (4.6%) | 2 | – | 2 (100%) | 6 (8.5%) | 4 | – | 4 (100%) | 7 (7.5%) |

| HPV-70 | 1 | – | 1 (100%) | 1 (4.4%) | 0 | – | – | 1 (1.4%) | 1 | – | 1 (100%) | 2 (2.1%) |

| HPV-73 | 1 | – | 1 (100%) | 1 (4.4%) | 1 | – | 1 (100%) | 1 (1.4%) | 2 | – | 2 (100%) | 2 (2.1%) |

| HPV-81 | 3 | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (4.8%) | 1 | – | 1 (100%) | 3 (4.2%) | 4 | 1 (25.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | 4 (4.3%) |

| HPV-82 | 1 | – | 1 (100%) | 0 (–) | 3 | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (66.7%) | 2 (2.9%) | 4 | 1 (25.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | 2 (2.2%) |

| HPV-83 | 1 | 1 (100%) | – | 2 (8.7%) | 2 | 1 (50.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 4 (5.6%) | 3 | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (33.3%) | 6 (6.4%) |

| HPV-84 | 4 | 1 (25.0%) | 3 (75.0%) | 0 (–) | 3 | – | 3 (100%) | 5 (7.1%) | 7 | 1 (14.3%) | 6 (85.7%) | 5 (5.6%) |

| CP6108 | 1 | 1 (100%) | – | 1 (4.4%) | 8 | 3 (37.5%) | 5 (62.5%) | 3 (4.6%) | 9 | 4 (44.4%) | 5 (55.6%) | 4 (4.6%) |

| All low risk infections‡ | 33 | 12 (36.4%) | 21 (63.6%) | 24 | 68 | 15 (22.1%) | 53 (77.9%) | 65 | 101 | 27 (26.7%) | 74 (73.3%) | 89 |

*Among those infected with that serotype at visit 1 (enrolment).

†Cumulative incidence among those uninfected with that serotype at enrolment.

‡Total number of genotype-specific infections among 97 women (24 in control and 73 in vaccine arm).

HPV, human papillomavirus.

Cumulative incidence of HR genotypes ranged from 1% to 12%, and was highest for HPV-51 (12.9%), HPV-39 (12.1%) and HPV-35 (8.7%) in the vaccine arm, and HPV-51 (9.1%), HPV-16 (4.8%) and HPV-58 (4.8%) in the control arm. LR genotypes cumulative incidence ranged from 2% to 10%, being highest for HPV-66 (8.7%), HPV-67 (8.5%) and HPV-61 (7.4%) in the vaccine arm, and HPV-53 (21.7%), HPV-6 (13.6%) and HPV-61 (9.1%) in the control arm.

In the control arm, there was one new HPV-16 and one new HPV-18 infection. In the vaccine arm, there was one new HPV-18 infection; the subject received two doses of vaccine.

Among HPV uninfected participants at enrolment, the incidence of any HPV infection was 76 (95% CI 46 to 126) per 100 person-years. Among those negative for all HR genotypes, the incidence of HR HPV infection was 51 (95% CI 46 to 126) per 100 person-years. Among those negative for all LR genotypes, the incidence of LR HPV infection was 54 (95% CI 35 to 82) per 100 person-years.

Of 97 participants who had HPV results at both time points, 65 (67.0%) were infected with a new HPV genotype by month 12 (table 1), 32 (33%) had persistent infection with ≥1 genotype and 62 (63.9%) had cleared ≥1 genotype by month 12. Only 11/70 (15.7%) participants who were infected at enrolment had cleared all their infections by month 12.

Discussion

An extremely high prevalence of HPV infection was observed in HIV negative sexually active girls and young women with normal cervical cytology in Tanzania. HPV-45, -16, -58 and -52 were the most prevalent types. The most common types worldwide in women with normal cytology in a large meta-analysis also included HPV-16 and -58 as well as other HPV genotypes that were less common in our study (HPV-18, -52, -31).4 In women with normal cervical cytology and in cervical cancer cases, HPV-45 was reported to be more common in sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America than other regions.4 8

The peak in HPV prevalence in young sexually active girls followed by a decrease in prevalence in older female subjects has been described in other studies3 9 10 but our study also adds information on acquisition of infection in the years following sexual debut.

In the present study, infection with multiple HPV types was common and observed in over 50% of the sexually active cohort. Younger age (<30 years) has been associated with multiple cervical HPV infections in many studies, including population-based studies in Colombia and a trial cohort in the UK.11 12 This may be due to a lack of natural immunity to HPV during the initial years of sexual activity but may also be due to numbers and characteristics of sexual partners.

A number of factors including age, number of sexual partners, age at menarche, hormonal contraceptives, HIV infection and smoking have been associated with HPV infection.9 11 13 Only age was a significant risk factor for HPV infection in this study. Younger age at sexual debut was not associated with HPV infection although this was associated with HR HPV in population-based studies in Nigeria and Uganda.14 15 Cigarette smoking, rare in our study population, was associated with HR HPV in the above Ugandan study and has been associated with prevalent and persistent HPV in other countries.15–17 Although our OR point estimates suggest that there may be an association with factors such as hormonal contraception, or more frequent condom use, these results should be interpreted with caution as our power to detect a significant association was low, and both variables may be a marker of more frequent sexual intercourse or with higher risk partners. Furthermore, since HPV infection is common, the OR should not be interpreted as a risk ratio; for example, with 68% prevalence in those not using hormonal contraception, an OR of 2 reflects a 19% increase in risk.

Cumulative HPV incidence in sexually active young women is high in developed countries. One US study found a cumulative 36 month incidence of 43% in college students.18 HPV incidence was also high in our study and infection with new HPV types was acquired in two-thirds of sexually active participants over 1 year. This may be an underestimate of the true incidence since some undetected HPV infections may have been acquired and lost between enrolment and 12 months. A recent study of 380 Ugandan women followed for a median of 18.5 months found an HPV incidence of 30.5/100 person-years with a higher incidence of HR than LR types.19 Reasons for the high incidence reported in our study are unclear since we have limited data on type and age of sexual partners but our results provide an indication of the high infection pressure for HPV in this setting.

Transmission of HPV appears extremely efficient in the early years of sexual activity in this population, with around two-thirds of girls acquiring HPV infection within the first few years following sexual debut. Although over a quarter of participants experienced persistent HPV infection, a predictor for cervical lesion development,20 most infections were transitory and 73% of HPV genotype-specific infections were cleared within 12 months. Similar clearance rates have been observed in studies in developed countries.21 The median duration of infection in young sexually active girls in a US study was 8 months.18 A Brazilian study found that 12-month clearance was higher for LR HPV than for HR HPV types22 but this was not seen in our study or in a Colombian study.23 Our study was not powered to measure the effect of vaccine on HPV incidence or persistence.

A high prevalence of HPV infection in young women does not necessarily translate to a high rate of persistent infection, a prerequisite for development of precancerous and cancerous lesions, since most women should clear their HPV infections. The high infection pressure for HPV in this setting means some persistent infections will develop and are likely to lead to higher rates of cervical cancer than observed in developed countries since there is an absence of adequate screening and treatment programmes. The risk of developing cervical cancer will obviously be increased with HIV infection. Recent data suggest that HPV-16 and -18 are associated with 70% or more of cervical cancer cases in most of the world including sub-Saharan Africa.13 24–26 Given the absence of widespread screening programmes in East Africa, our data therefore suggest that primary prevention through HPV vaccination before sexual debut is an important public health intervention to control this disease.

The strengths of our study are its prospective design which included young women around the age of sexual debut and our testing for many HPV genotypes. Limitations include that we did not sample HPV in girls who did not report sexual activity, so limiting our scope for analysis of the association of HPV infection with number of sexual partners. In addition, since under-reporting of sexual activity with face-to-face interviews has been well documented among young women in Africa,27 28 and HPV has been detected in 2% of vaginal samples from virgins in the USA,29 by not sampling all subjects we could have underestimated the prevalence of HPV infection. This study was not representative of all young women in our setting since HIV positive participants and participants with >6 lifetime sexual partners, who might be at higher risk of HPV infection, were excluded and so our observed prevalence and incidence of HPV is likely to be conservative. Participants were only followed for 12 months, so limiting our ability to detect clearance or persistence of genotype-specific HPV infection. Last, our small sample size gave us limited ability to detect associations of HPV with sexual behaviour and other variables. For risk factors with prevalences of less than 25%, we had less than 70% power to detect even very strong associations (eg, an OR=3) with HPV infection.

In conclusion, we found an extremely high prevalence and incidence of HPV infection in young HIV negative Tanzanian female subjects. The high rates of HPV infection and poor access to cervical screening services have led to Tanzania having one of the highest rates of cervical cancer in the world1 and therefore it is positive news that Tanzania is planning a national HPV vaccination programme.30 Since sexual activity was reported in girls aged 14 years and above in this cohort, and because prevalent HPV infection rises quickly after sexual debut,31 and vaccination is most efficacious in female subjects before they acquire HPV infection, ideally girls <14-years-old should be targeted for vaccination in this population.

Key messages.

Young Tanzanian women in Mwanza have a very high prevalence and incidence of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, the primary cause of cervical cancer.

HPV is rapidly acquired after sexual debut.

HPV vaccination represents an opportunity for primary prevention and should be provided prior to initiation of sexual intercourse.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Ministry of Health & Social Welfare for permission to conduct and publish the study, Roche for providing the test kits, the UNIC HPV laboratory in Barcelona and Jose Godliness and Ana Esteban for performing the HPV assays.

Footnotes

Contributors: DW-J, RJH and PM conceived the study. DWJ prepared the protocol and had overall responsibility for supervision and conduct of the study. SK supervised the study activities and BG provided clinical supervision. JB coordinated the study and BK supervised the trial teams and data collection. Data analysis was done by KB. Laboratory analysis was supervised by JC and AA in Mwanza and by SdS in Barcelona. DWJ prepared the first draft of the manuscript. All authors commented on and contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals was the funding source for the HPV-021 trial. Additional funding came from the UK Department for International Development. Partial salary support for DWJ and AA and salary support for JB and BK came from GSK Biologicals.

Competing interests: DWJ, PM and SS have received grant support through their institutions from GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals. SS has also received grants from Merck & Co.

Ethics approval: London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, UK and National Institute for Medical Research, Tanzania.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer 2010;127:2893–917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Sanjose S, Diaz M, Castellsague X, et al. Worldwide prevalence and genotype distribution of cervical human papillomavirus DNA in women with normal cytology: a meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2007;7:453–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith JS, Melendy A, Rana RK, et al. Age-specific prevalence of infection with human papillomavirus in females: a global review. J Adolesc Health 2008;43:S5–25, S25 e1–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruni L, Diaz M, Castellsague X, et al. Cervical human papillomavirus prevalence in 5 continents: meta-analysis of 1 million women with normal cytological findings. J Infect Dis 2010;202:1789–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watson-Jones D, Baisley K, Ponsiano R, et al. HPV vaccination in Tanzanian schoolgirls: cluster-randomised trial comparing two vaccine delivery strategies. J Infect Dis 2012;206:678–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salif Sow P, Watson-Jones D, Kiviat N, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of human papillomavirus-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine: a randomised trial in HIV-seronegative African females. J Infect Dis Published Online First: 13 Dec 2012. doi:10.1093/infdis/jis619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K, et al. A review of human carcinogens—Part B: biological agents. Lancet Oncol 2009;10:321–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ndiaye C, Alemany L, Ndiaye N, et al. Human papillomavirus distribution in invasive cervical carcinoma in sub-Saharan Africa: could HIV explain the differences? Trop Med Int Health. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12004. Published Online First: 29 Oct 2012. doi:10.1111/tmi.12004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sangwa-Lugoma G, Ramanakumar AV, Mahmud S, et al. Prevalence and determinants of high-risk human papillomavirus infection in women from a Sub-Saharan African community. Sex Transm Dis 2011;38:308–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dartell M, Rasch V, Kahesa C, et al. Human papillomavirus prevalence and type distribution in 3603 HIV-positive and HIV-negative women in the general population of Tanzania: the PROTECT study. Sex Transm Dis 2012;39:201–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molano M, Posso H, Weiderpass E, et al. Prevalence and determinants of HPV infection among Colombian women with normal cytology. Br J Cancer 2002;87:324–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sargent A, Bailey A, Almonte M, et al. Prevalence of type-specific HPV infection by age and grade of cervical cytology: data from the ARTISTIC trial. Br J Cancer 2008:1704–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Louie KS, de Sanjose S, Mayaud P. Epidemiology and prevention of human papillomavirus and cervical cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: a comprehensive review. Trop Med Int Health 2009;14:1287–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clarke MA, Gage JC, Ajenifuja KO, et al. A population-based cross-sectional study of age-specific risk factors for high risk human papillomavirus prevalence in rural Nigeria. Infect Agent Cancer 2011;6:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asiimwe S, Whalen CC, Tisch DJ, et al. Prevalence and predictors of high-risk human papillomavirus infection in a population-based sample of women in rural Uganda. Int J STD AIDS 2008;19:605–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bell MC, Schmidt-Grimminger D, Jacobsen C, et al. Risk factors for HPV infection among American Indian and White women in the Northern Plains. Gynecol Oncol 2011;121:532–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maucort-Boulch D, Plummer M, Castle PE, et al. Predictors of human papillomavirus persistence among women with equivocal or mildly abnormal cytology. Int J Cancer 2010;126:684–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho GY, Bierman R, Beardsley L, et al. Natural history of cervicovaginal papillomavirus infection in young women. N Engl J Med 1998;338:423–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Banura C, Franceschi S, van Doorn LJ, et al. Prevalence, incidence and clearance of human papillomavirus infection among young primiparous pregnant women in Kampala, Uganda. Int J Cancer 2008;123:2180–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trottier H, Mahmud SM, Lindsay L, et al. Persistence of an incident human papillomavirus infection and timing of cervical lesions in previously unexposed young women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009;18:854–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Insinga RP, Perez G, Wheeler CM, et al. Incident cervical HPV infections in young women: transition probabilities for CIN and infection clearance. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2011;20:287–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Franco EL, Villa LL, Sobrinho JP, et al. Epidemiology of acquisition and clearance of cervical human papillomavirus infection in women from a high-risk area for cervical cancer. J Infect Dis 1999;180:1415–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Molano M, Van den Brule A, Plummer M, et al. Determinants of clearance of human papillomavirus infections in Colombian women with normal cytology: a population-based, 5-year follow-up study. Am J Epidemiol 2003;158:486–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Sanjose S, Quint WG, Alemany L, et al. Human papillomavirus genotype attribution in invasive cervical cancer: a retrospective cross-sectional worldwide study. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:1048–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li N, Franceschi S, Howell-Jones R, et al. Human papillomavirus type distribution in 30,848 invasive cervical cancers worldwide: variation by geographical region, histological type and year of publication. Int J Cancer 2011;128:927–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDonald AC, Denny L, Wang C, et al. Distribution of high-risk human papillomavirus genotypes among HIV-negative women with and without cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in South Africa. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e44332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nnko S, Boerma JT, Urassa M, et al. Secretive females or swaggering males? An assessment of the quality of sexual partnership reporting in rural Tanzania. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:299–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Langhaug LF, Cheung YB, Pascoe SJ, et al. How you ask really matters: randomised comparison of four sexual behaviour questionnaire delivery modes in Zimbabwean youth. Sex Transm Infect 2011;87:165–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Winer RL, Lee SK, Hughes JP, et al. Genital human papillomavirus infection: incidence and risk factors in a cohort of female university students. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157:218–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.In2eastafrica http://in2eastafrica.net/tanzania-cervical-cancer-vaccination-for-schoolgirls-underway-for/ (accessed 21 Jul 2012).

- 31.Winer RL, Feng Q, Hughes JP, et al. Risk of female human papillomavirus acquisition associated with first male sex partner. J Infect Dis 2008;197:279–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.