Persons with mental illness are at higher risk of developing life-threatening physical conditions or dying prematurely [1], and several studies have reported improvements in health status when patients received integrated services. By integrating behavioral health services with primary care services, we can improve health care quality, preventive care practices, and health outcomes and reduce fragmented health care delivery for people who have mental illness or addictions and physical health problems [2, 3]. An emerging model for improving health care quality in the USA is the patient-centered medical home (PCMH). This model may provide an ideal way to integrate behavioral health and primary care services [4], particularly for persons with chronic conditions such as diabetes [5, 6] and hypertension [7, 8]. Already, some federal programs and state policies are supporting this approach as a way to integrate and improve health care services for persons with behavioral and physical health problems.

BACKGROUND

The PCMH is a rapidly evolving, promising model that uses a team approach and a focus on the “whole person” to deliver high-quality, comprehensive, coordinated, cost-effective, patient-centered, and culturally appropriate health care services [4]. It encourages health care providers to use clinical decision-support tools and recommended preventive care practices to improve health care quality for all patients. It also encourages patients and families to be actively involved in managing and making decisions about their own care [9].

The concept of the medical home was introduced by the American Academy of Pediatrics in the 1960s. Pediatricians caring for children with chronic illnesses proposed that each child’s care be coordinated by a team of specialists and that all information about the child be kept in a central location. The success of this approach led other physician groups to embrace the medical home concept for adult patients. In 2007, four national organizations—the American College of Physicians, American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, and American Osteopathic Association—issued the following seven joint principles of PCMH: (1) an ongoing relationship between the patient and a personal physician, (2) a physician-directed team to take responsibility for the patient’s care, (3) a whole-person orientation that addresses care across all stages of life, (4) coordination and integration of care across the health care system, (5) quality and safety standards, (6) enhanced access to care, and (7) payment that recognizes the added value of the PCMH approach [10]. The American Medical Association adopted these principles in 2008.

Although primary care services have historically focused on physical health, the PCMH model provides a way to integrate behavioral and mental health care into primary care services [11], especially for treating persons with depression, diabetes, anxiety, or substance abuse problems. One study found significant improvements in symptom severity, treatment response, and remission for depression and anxiety disorder after primary care and behavioral health services were integrated [12]. Another study found significant improvements in key measures of health (e.g., blood sugar and blood pressure levels, symptoms of depression) in patients with depression and poorly controlled diabetes, coronary heart disease, or both after they participated in a patient-centered intervention [13]. For example, the Cherokee Health Systems of Tennessee provides behavioral health consultants as full-time members of primary care teams and embeds primary care providers into specialty behavioral health teams, in over 40 clinical sites [11].

STRATEGIES

Several federal agencies are supporting PCMH demonstration projects that integrate primary care and behavioral health services to address the needs of persons with mental illness and substance abuse problems. Examples include the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), Healthcare Resource and Service Administration (HRSA), and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). The Center for Integrated Health Solutions (jointly funded by SAMHSA and HRSA and run by the National Council for Community Behavioral Healthcare) provides training and technical assistance designed to improve the effectiveness, efficiency, and sustainability of integrated health services to 64 community behavioral health organizations that collectively have received more than $26.2 million from Primary and Behavioral Health Care Integration grants, community health centers, and other primary care and behavioral health organizations [2, 14]. The center monitors activities and models across the country and shares best practices with primary care and behavioral health professionals. The Integrated Care Resource Center, which is a national CMS initiative, encourages states to integrate physical and behavioral health services to improve the quality and cost-effectiveness of care for high-need, high-cost Medicaid beneficiaries [15].

To ensure the quality and effectiveness of the PCMH model, data have to be collected and evaluated. At the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), researchers are collecting data on PCMH policies at the state level, including those that address behavioral health. This information will help researchers and policy makers identify which programs and policies are working. The data will be included in a new database that CDC is developing to track all state policies designed to prevent chronic disease and promote health.

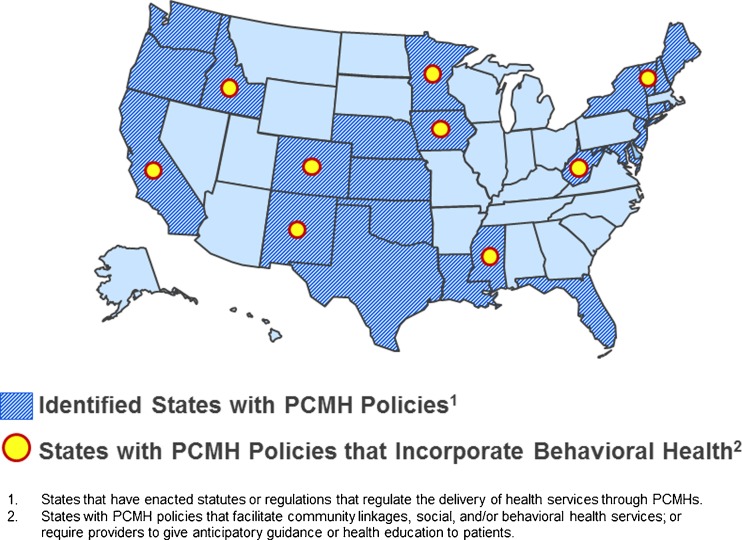

Figure 1 shows the 24 states that have adopted policies, either through a statutory or regulatory process, to regulate the delivery of health services through PCMHs as of February 2012. Of these states, nine have enacted PCMH policies that integrate behavioral health either by promoting links to behavioral health services or by establishing regulations for health care providers who give anticipatory guidance or health education to patients.

Fig. 1.

States with patient-centered medical home policies that include behavioral health services

States that either mandate or authorize PCMHs to promote links with behavioral health services are California, Idaho, Iowa, Minnesota, Mississippi, New Mexico, Vermont, and West Virginia. All of these states except Iowa have policies that specifically mention mental health, substance abuse, or behavioral health services. These policies vary by state. For example, New Mexico’s policy is limited to PCMHs for children [16], whereas Mississippi’s policy is only a statement of legislative findings that encourage PCMH adoption [17].

States that either mandate or authorize health care providers to give anticipatory guidance or health education to their patients are California, Colorado, New Mexico, and Vermont. These policies also vary by state. For example, New Mexico’s policy states that the components of the PCMH “may include … health education, [and] health promotion” [16]. In contrast, Colorado’s policy requires that “at a minimum,” PCMHs must provide anticipatory guidance and health education to patients [18].

CONCLUSION

Several strategies are being used at federal and state levels to promote the creation of PCMHs that integrate behavioral health care with primary care services. Although further research is needed, the PCMH model offers a promising opportunity to improve both the physical and mental health of populations in need and to reduce health care costs and the current fragmentation of services.

Acknowledgments

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.Mental health, United States 2010. HHS Publication No. SMA12-4681. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions. SAMHSA PBHCI program. Available at: http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/about-us/pbhci. Accessed 23 May 2012.

- 3.Behavioral health/primary care integration and the person-centered healthcare home. Washington, DC: National Council for Community Behavioral Healthcare; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Patient centered medical home resource center. Defining the PCMH. Available at: http://pcmh.ahrq.gov/portal/server.pt/community/pcmh__home/1483/PCMH_Defining%20the%20PCMH_v2. Accessed 23 May 2012.

- 5.Campayo A, Gomez-Biel CH, Lobo A. Diabetes and depression. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2011;13(1):26–30. doi: 10.1007/s11920-010-0165-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mezuk B, Eaton WW, Albrecht S, Golden SH. Depression and type 2 diabetes over the lifespan: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(12):2383–2390. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davidson K, Jonas BS, Dixon KE, Markovitz JH. Do depression symptoms predict early hypertension incidence in young adults in the CARDIA study? Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160(10):1495–1500. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.10.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scalco AZ, Scalco MZ, Azul JB, Lotufo NF. Hypertension and depression. Clinics (São Paulo, Brazil) 2005;60(3):241–250. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322005000300010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scholle SH, Torda P, Peikes D, Han E, Genevro J. Engaging patients and families in the medical home. AHRQ Publication No. 10-0083-EF. Washington, DC: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American College of Physicians, American Osteopathic Association. Joint principles of the patient-centered medical home. Available at: http://www.pcpcc.net/joint-principles. Accessed 23 May 2012.

- 11.Amiel JM, Pincus HA. The medical home model: new opportunities for psychiatric services in the United States. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2011;24(6):562–568. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32834baa97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Integration of mental health/substance abuse and primary care. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 173. AHRQ Publication No. 09-E003. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von KM, Ciechanowski P, Ludman EJ, Young B, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2010;363(27):2611–2620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions. About CIHS. Available at: http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/about-us/about-cihs. Accessed 23 May 2012.

- 15.Integrated Care Resource Center, State Options for Integrating Physical and Behavioral Healthcare. Technical Assistance Brief. October 2011.

- 16.Public Assistance Act N.M. Stat. Ann. § 27-2-12.15. 27-2-12.15. 6-19-2009. New Mexico Statutes 1978. 3-30-2012. Ref Type: Statute.

- 17.Patient Centered Medical Home Principles Miss. Code Ann. § 41-3-61. 41-3-61. 7-1-2010. Mississippi Code 1972 Annotated. 3-30-2012. Ref Type: Statute.

- 18.Health—Medical Homes For Children—Appropriations Colo. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 25.5-1-103. 25.5-1-103. 5-31-2007. Colorado Revised Statutes. 3-30-2012. Ref Type: Statute.