ABSTRACT

Reviews of internet-based behaviour-change interventions have shown that they can be effective but there is considerable heterogeneity and effect sizes are generally small. In order to advance science and technology in this area, it is essential to be able to build on principles and evidence of behaviour change in an incremental manner. We report the development of an interactive smoking cessation website, StopAdvisor, designed to be attractive and effective across the social spectrum. It was informed by a broad motivational theory (PRIME), empirical evidence, web-design expertise, and user-testing. The intervention was developed using an open-source web-development platform, ‘LifeGuide’, designed to facilitate optimisation and collaboration. We identified 19 theoretical propositions, 33 evidence- or theory-based behaviour change techniques, 26 web-design principles and nine principles from user-testing. These were synthesised to create the website, ‘StopAdvisor’ (see http://www.lifeguideonline.org/player/play/stopadvisordemonstration). The systematic and transparent application of theory, evidence, web-design expertise and user-testing within an open-source development platform can provide a basis for multi-phase optimisation contributing to an ‘incremental technology’ of behaviour change.

KEYWORDS: Smoking cessation intervention, Internet-based, Website, Theory-based

BACKGROUND

Reviews of internet-based behaviour-change interventions have shown that they can be effective but there is considerable heterogeneity and effect sizes are generally small [1–4]. In order to advance science and technology in this area, it is essential to be able to build on principles and evidence of behaviour change in an incremental manner. Unfortunately, internet-based interventions tend to be treated as ‘black boxes’ with limited description of their content or the principles used in their development. As a result, once such interventions have been tested, whether or not they turn out to be effective, subsequent development cannot take advantage of the previous experience. This paper describes the development of a theory-based, interactive smoking cessation website, StopAdvisor, designed to be attractive and effective across the social spectrum. We used an open-source web-development platform, LifeGuide (www.lifeguideonline.org), as a starting point for a process of optimisation of behaviour change technology [5]. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to be fully transparent about the content and development of an internet-based behaviour change intervention.

Since smoking remains the largest single preventable cause of premature death and illness worldwide [6], there is a pressing need to find better ways of helping smokers to stop. The most effective smoking cessation intervention involves face-to-face behavioural support combined with medication [7]. However, even in the UK where it is provided free of charge to any smoker who wants it, use of behavioural support is rare, at approximately 5 % of quit attempts [8]. Although telephone support can be effective, few smokers use it [9]. The internet is a largely untapped mode of support which has the potential for wide reach and for helping people who do not wish to engage in face-to-face behavioural support [10, 11]. It can also have extremely low cost per user [12].

The potential effectiveness of internet-based smoking cessation interventions has been the subject of three recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses [1–3]. These reported a significant effect overall but considerable heterogeneity, not only in design and outcomes, but also in the quality and usability of the specific online interventions. This makes smoking cessation highly suitable for the application of transparent design principles to begin the process of intervention optimisation.

In addition to transparency in reporting content and development, open-source software is another important factor that can promote the optimisation of internet interventions. Open-source software is available in source code form and provided under a free software license. LifeGuide is a new open-source development platform and has been used by researchers to create websites which provide tailored long-term support for behaviour change [13]. The platform facilitates intervention development by allowing researchers to rapidly test the effects of intervention components and easily modify and improve components based on early findings. It also facilitates evaluation and dissemination of successful intervention components, allowing researchers to pool data (e.g. for meta-analysis of the effects of intervention components), and share components for use in future interventions. Such flexibility provides the ideal platform to build an incremental technology of behaviour change, with researchers able to alter specific features of the intervention and examine the resulting effects. Experimentation with internet-based interventions has the additional advantage of addressing concerns about the fidelity of intervention delivery by precisely recording which uniform BCTs are delivered to each participant [14]. For these reasons, StopAdvisor was developed in LifeGuide.

Sources of information that can contribute to principles of internet intervention design include psychological theory, direct evidence of effectiveness, empirically derived principles of web design, and user testing. Psychological theory can provide broad guidance on the approach and appropriate targets for specific components of the website (e.g. cravings, self-confidence). Direct evidence on effectiveness of particular components can suggest what components should be included. Web-design principles are crucial to ensuring that the user experience is positive and functional. User testing is required because theory, prior evidence, and web-design principles cannot take account of the multitude of factors that may come into play or the effects of interactions between those factors in a given intervention within a particular context.

A final important consideration when developing internet interventions is the ‘digital divide’: disadvantaged smokers tend to use the Internet less [15]. Disadvantaged smokers also want, and try, to stop as much as other smokers but find it more difficult [16]. It is therefore vital that disadvantaged groups are not excluded by their relative lack of access and familiarity. To this end, there is evidence that these digital divide issues can be mitigated by including disadvantaged groups in the design process [17, 18]. Therefore, in an attempt to make the current intervention effective across the social spectrum our user-testing was conducted with disadvantaged smokers. Disadvantage was operationalised on the basis of occupation and educational attainment.

This paper describes the process of development of the StopAdvisor intervention under the headings of: theory, empirical evidence, expertise in website design and user-testing with a panel of disadvantaged smokers. It also provides a full description of the intervention, which is currently being evaluated in a randomised controlled trial (ISRCTN99820519).

METHODS

In this section, we outline the processes by which we selected and refined intervention content. The detailed description of the content is presented in the Results section.

Both the content and format of the intervention were developed based on principles generated by (a) the PRIME theory of motivation, (b) empirical evidence from the field of smoking cessation and behavioural science more generally, (c) the experience of members of the research team in designing web-based behaviour change interventions, and (d) engaging the target population in user-testing. The principles arising from these sources were applied to intervention design by a multidisciplinary team reflecting expertise in the above areas.

Theory

PRIME Theory was chosen because it incorporates the different facets of motivation that have been shown to be important in cigarette addiction and smoking cessation [19]. It is a broad theory of motivation that states that behaviour is determined on a moment-to-moment basis. At any given moment, action arises from the strongest of competing impulses and inhibitions, which arise from multiple and inconstant sources including stimulus–impulse associations and motives (feelings of anticipated pleasure, satisfaction or relief). Motives can be generated by evaluations (beliefs about what is good and bad), which are in turn often generated by plans (self-conscious intentions regarding future action). Applied to smoking cessation interventions, PRIME Theory would require smokers to make a personal rule (plan) not to smoke. The rule must have very clear boundaries and be linked to emotionally important aspects of identity in order to generate sufficiently powerful desires to inhibit strong urges to smoke that arise on a moment to moment basis. In order to increase the success of smokers' abilities to inhibit urges, an internet-based intervention should visually encourage an identity shift from smoker to non-smoker, and be simple to use, highly rewarding and reinforcing. In addition, the probability of success would be enhanced by promoting avoidance of cues that elicit urges to smoke, specific actions to mitigate those urges or prevent them resulting in lapses, effective use of medication to reduce smoking urges, and adoption of strategies that maintain mental energy required to exercise self-control. The emphasis should be on preventing, minimising and combating momentary impulses to smoke. As much attention should be placed on generating desire to use the website as to the effect of the website in addressing urges to smoke. This means paying close attention to aesthetic appeal and minimising demands on the user. An overview of PRIME theory as it applies to this intervention was written by RW and presented to the study team for discussion. The key theoretical principles relevant to the intervention were agreed.

Empirical evidence: smoking and behavioural science

Reliable taxonomies of behaviour change techniques (BCTs) used in behavioural support for smoking cessation have been developed and used to investigate associations between specific BCTs and successful quitting [20–23]. On the basis of these associations, other direct evidence on the effectiveness of particular techniques (e.g. [24, 25]), and PRIME theory, a core set of BCTs was selected by the study team and linked together in a variety of ways consistent with their use in the evidence-based and successful NHS Stop Smoking Services. This approach is based on an expert Stop Smoking Advisor being both a ready source of information that smokers trying to stop may want or need, and a guide to help the smoker through the process of stopping, using a structured quit plan. StopAdvisor was designed to follow as far as possible the quit plan that would be in operation in a well-run Stop Smoking Service, with an emphasis on those BCTs that are well suited to delivery by internet. It aimed to simulate personal contact as much as possible.

Expertise in website design

Team members’ expertise in website development came from the experience of leading and participating in the development of a number of interactive web-based interventions [13, 26–31]. This produced principles of how to maximise engagement, for example by optimising the aesthetics, credibility and interactivity of the site [32] and employing a hybrid architecture combining tunnelled exposure to key messages and choice of content from a menu [33].Website content was guided by an assessment of the balance between (1) maintaining motivation to stop and maximising self-regulatory capacity and (2) avoiding burdening users in a way that would deter them from making further use of the website. Every BCT that was included in the site was assessed in these terms.

User-testing with a panel of disadvantaged smokers

We conducted user-testing of the prototype website, developed on the basis of the above principles, to assess preliminary functionality, acceptability, usability and engagement. The intervention was piloted with 24 smokers who reported either having no post-age 18 qualifications or one of the following occupational categories as described within the National Statistics Socio-Economic Classification [34]: ‘never worked’, ‘long-term unemployed’, or ‘routine and manual’. Eligible smokers also needed to express an interest in making a quit attempt and be willing to use a stop-smoking website. Recruitment was via an advertisement placed in a regional free newspaper and a database of smokers who had volunteered to be contacted about smoking-related studies. This qualitative piloting involved both in-depth interviews and ‘think aloud’ testing [35]. Interviews were designed to inductively explore beliefs surrounding use of an internet intervention to aid smoking cessation. The ‘think aloud’ method involved users working through sections of the intervention and saying whatever came to mind as they did so. The interviews were recorded and transcribed. The data were analysed to identify both the general beliefs of the target group and the specific content, format and navigation-related feedback. These beliefs and feedback were used to modify the relevant components of the intervention.

The user testing (described below) was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Southampton (Study ID: 1122).

Procedure

First, the team agreed the theoretical basis and principles underpinning the intervention. Next, relevant literature was reviewed and then monitored for updates using automatic alerts. Having established theoretical and empirical principles, the team reached consensus over the overarching theme and design. From this stage onward development meetings were formulaic: the team met regularly to evaluate progress, plan the future allocation of resources, resolve implementation issues, and present and review new evidence arising from the literature, conferences or user-testing.

Draft versions of all pages were created in LifeGuide’s Virtual Research Environment (VRE), allowing fluid online feedback, comments and amendments on their implementation. Applying the theoretical, empirical and design principles within the VRE, the development process involved an iterative process of

Drafting sections of the website

Comments from study team members and expert advisors (e.g. graphic designer and professional writer)

Revising those sections according to the comments

Testing the content with a panel of disadvantaged smokers

Linking sections together and applying the above to the larger sections until the full website was completed

Beyond the VRE, an overall flow-chart of the site structure and manual were developed and maintained in the latter stages of development. These off-line documents provided a useful and complementary overview because by this stage the website was extensively tunnelled and tailored from the perspective of an end-user.

RESULTS

Principles informing intervention development

From PRIME theory, 19 principles were identified as key to the intervention: eight that directly addressed motivation, three addressing self-regulatory capacity and skills, one addressing adjuvant activities and seven promoting engagement with the intervention (Table 1).On the basis of these principles and empirical evidence on the effectiveness of particular techniques, a total of 33 BCTs were included that are labelled within the ‘smoking taxonomy’ [20] as BM1–10; BS1–4, 6–8, 10–11; A1–3, 5; RD1–2; RI4; RC1, 4–6, 8–10.Twenty-eight principles of website design were identified by the study team (Table 2) and a further nine were identified by user-testing (Table 3). An illustrative list of intervention components resulting from the iterative process of applying principles and BCTs to intervention development are shown in Table 4.

Table 1.

PRIME Theory principles underlying intervention design

| Directly address motivation |

| 1. Establish a very clear mental image of the goal of becoming an ex-smoker and how to get to it with the help of the quit plan. |

| 2. Construct the personal rule such that it will generate strong resolve whenever needed (clear boundaries: ‘not even a puff’, achievable: ‘day at a time if necessary’, applicable to every relevant situation: ‘no matter what’). |

| 3. Associate adhering to the rule with things to which the smoker has strong emotional attachment/central aspects of their identity (e.g. good role model for others, protecting loved ones). |

| 4. Develop new sources of desire not to smoke and maximise the impact of existing sources of desire (e.g. wanting to keep the achievement to date). |

| 5. Change aspects of identity that promote smoking (e.g. an ‘unhealthy’ person) and foster aspects of identity that promote not smoking (e.g. a healthy persona), in a way that supports rather than conflicts with other core aspects of identity (e.g. a rebel). |

| 6. Change beliefs that generate a desire to smoke (e.g. that smoking helps with stress) in such a way that negative images of the results of smoking are generated. |

| 7. Maximise the experience of reward they obtain from moving towards their goal of becoming an ex-smoker (e.g. by helping them visualise their achievement). |

| 8. When describing what to expect ensure that it is phrased positively but realistically. |

| Maximise self-regulatory capacity and skills |

| 9. Avoid cues that will trigger strong urges to smoke (e.g. through social or environmental restructuring). |

| 10. Develop effective ways of distracting attention from smoking cues in the environment and from urges to smoke when they occur (e.g. by developing as routine activity). |

| 11. Maximise levels of mental energy available to exercise self-control (e.g. by teaching ways of avoiding or reducing stress). |

| Make effective use of adjuvant activities |

| 12. Make most effective use of medications that reduce the urges to smoke (e.g. by making sure that they choose the best medication, have appropriate expectations, use it properly and for long enough, and are not put off by side effects). |

| Promoting engagement |

| 13. Establish a ‘rapport’ between the smoker and personification of the website (e.g. by creating a visual sense of the team behind the website who want the smoker to succeed) and use language that expresses shared understandings and empathy. Give feedback to the user to show that the program ‘understands’ his or her situation. |

| 14. Set up clear expectations concerning how the site will be used early on. |

| 15. Keep demands on the smoker to a minimum (e.g. for every question asked of the smoker calculate the cost in terms of making the site unattractive versus the benefit in terms of helping to tailor the website). |

| 16. Make use of the site as habitual as possible in terms of the location of different elements, consistent forms of interaction and clear associations between goals that smokers may have and actions needed to achieve these. |

| 17. Keep main pages as simple and visually appealing as possible but encourage and make it easy for smokers to explore the site to find out more information. |

| 18. Always provide users with a rewarding experience when they visit the website. Each interaction must provide pleasure, satisfaction and/or relief, combat a tendency to habituate to website materials, and establish strong anticipated pleasure, satisfaction or relief for the next session. Do not require users to enter more than a few responses on a page without immediately rewarding them with answers to concerns, advice that is perceived as useful and information about themselves that they find interesting. |

| 19. From the user’s perspective the website must provide desired information and advice and not be an overt attempt to motivate. |

Table 2.

Principles of website design identified by the study team

| 1. Where possible use images (photos, graphics, or video) to convey information. |

| 2. Present new information each time the website is accessed. |

| 3. Promote engagement by using text messaging and emails. |

| 4. Give control, choice and personal relevance by asking questions. |

| 5. Keep text as brief as possible. |

| 6. Use bullet points. |

| 7. Try to avoid grouping more than two sentences together. |

| 8. Use a hybrid architecture to combine tunnelled exposure to key messages and choice of content from menus. |

| 9. Provide additional information in both the menus and dialogue sessions for those who want it. |

| 10. Navigation must be consistent and straightforward. |

| 11. Avoid a patronising tone in the text. |

| 12. Reading level to age 14. |

| 13. Make as interactive as possible — questions, tailored feedback, videos, audio, gallery, emails, text messaging, etc. |

| 14. The website must look professional. |

| 15. Layout pages to avoid scrolling on the most popular screen resolution of 1024 × 768. |

| 16. Keep consistency throughout with regard to layout and grammar. |

| 17. Avoid small text. |

| 18. Avoid replication. |

| 19. Remove all unnecessary words. |

| 20. Try not to use words longer than six letters where possible. |

| 21. Personalise as much as possible. |

| 22. Use ‘chatty’ everyday language, avoiding formality as much as possible. |

| 23. Express content in brief and specific terms. |

| 24. Structure sections to take no more than 5–10 min of the users time at each login. |

| 25. Feature an interactive component in each section of the text, either through the form of a question, text entry, video or audio clips. |

| 26. Emphasise choice as much as is possible. |

Table 3.

Principles of website design identified by user-testing

| 1. Make font consistent on all buttons. Also, include richer tone buttons, especially early on. |

| 2. Keep number of fonts in main banner logo to a minimum. |

| 3. Increase the number of pages with logos and pictures on them. |

| 4. Make greater use of bold to emphasise key points and improve design. |

| 5. Repeatedly emphasise the basic structure of the site and the programme, including a screencast video to demonstrate the site. |

| 6. Remove unhelpful jargon and terminology (e.g. NRT, intervention, medication). |

| 7. Manage expectations about the site in general, and specifically about terms like personalised and tailoring by explaining them. |

| 8. Encourage regular use of the site to overcome the belief it should only be used if ‘things are going badly’. |

| 9. Personalise the ‘source’ of StopAdvisor (e.g. expanding the ‘about team’ section and adding smoking histories). |

Table 4.

StopAdvisor components: description and rationale

| Intervention component | PRIME Theory principle(s) | BCT(s) | Website expertise |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Text encouraging users to repeat to themselves: ‘Smoking is not an option’. Explain and introduce a motto: ‘Not a puff — no matter what’ and an image to accompany this. | Construct personal rule to generate strong resolve. | BM6 (Prompt commitment from the client there and then); BM8 (Strengthen ex-smoker identity); BM10 (Explain importance of abrupt cessation). | Eye catching image will be attractive. Provision of a simple motto that can be easily remembered can be taken away from the website and used/referred back to throughout the day. |

| 2. Text encourages users to spend some time thinking about who they want to be in the future. They are asked to consider positive identities they might wish to take on once they have successfully completed their quit attempt. | Associate non-smoking to central aspects of identity. | BM8 (Strengthen ex-smoker identity). | This exercise has a positive focus. This, importantly, may again associate positive experiences, or positive images, with use of the website and the programme in general — fostering engagement. |

| 3. Text offers reassurance and suggests high craving are a normal part of quitting smoking. | Develop new, and maximise impact of existing, sources of desire not to smoke. | BM5 (Provide normative information about others’ behaviour and experiences); RC1 (Build general rapport); RC6 (Provide information on withdrawal symptoms); RC10 (Provide reassurance). | Simple text may reassure users, and sustain effort to participate with the programme despite high cravings remaining. |

| 4. Users are required to identify reasons for wanting to stop smoking. Importantly, they are given space to engage with these elements. | Develop new, and maximise impact of existing, sources of desire not to smoke. | BM9 (Identify reasons for wanting and not wanting to smoke). | Using radio buttons encourages engagement with the site. The information will be presented back to the participants. |

| 5. Users are presented with key facts regarding how the body starts repairing itself immediately, as soon as the smoker stops. | Develop new, and maximise impact of existing, sources of desire not to smoke. | BM1 (Provide information on consequences of smoking and smoking cessation). | Facts can be presented in a quick and ‘punchy’ manner. This small amount of text carries a strong message regarding the benefits of quitting smoking. |

| 6. It will be suggested that users visualise, in some detail, being told they have a serious illness. | Develop new, and maximise impact of existing, sources of desire not to smoke/Change aspects of identity that promote smoking. | BM1 (Provide information on consequences of smoking and smoking cessation); BM8 (Strengthen ex-smoker identity) | Strong use of mental imagery in this task will remind users of the negative health consequences of smoking. It is a simple task that is easy to imagine, thus promoting engagement. |

| 7. When users get to a certain point without smoking a cigarette (8–10 days or more) they will be asked to reflect on this positive progress and use it to build confidence and continue with the quit attempt. | Develop new, and maximise impact of existing, sources of desire not to smoke. | BM2 (Boost motivation and self efficacy); BM4 (Provide rewards contingent on successfully stopping smoking); RC1 (Build general rapport). | This positive message will be designed specifically to promote sustained engagement with the intervention. |

| 8. Users are encouraged to think about how well they are doing, and how they need to remember to reward themselves, by doing something they like — that does not remind them of smoking. They are provided with examples. | Develop new, and maximise impact of existing, sources of desire not to smoke/Maximise experience of reward from moving towards goal. | BM2 (Boost motivation and self efficacy); BM7 (Provide rewards contingent on effort or progress); BS10 (Advise on conserving mental resources). | This positive message aims to promote engagement by reminding users that a quit attempt need not be a struggle at all times. It may elicit positive affect, leading to a positive association with the website. |

| 9. Users are encouraged to visualise an image of smoking as a battle. They are to think of themselves as winning the battle. A catching image will be provided. | Maximise experience of reward from moving towards goal. | BM2 (Boost motivation and self efficacy). | An eye-catching image will be used draw attention to this message, focusing smokers’ attention on the goal at hand. |

| 10. A section will focus on the use of ‘buddies’ — teaming up with someone who is also trying to quit. Another will advise users on the potential benefits of telling family friends and colleagues. | Avoid cues that trigger urges to smoke. | BS3 (Facilitate action planning); BS11 (Advise on avoiding social cues for smoking); A2 (Advise on/facilitate use of social support). | This may promote the use of a network of social contacts to quit together. Users will be asked to type a specific plan for telling others, which will encourage engagement with the website. Additionally it provides another arm in the multifaceted approach to the intervention. |

| 11. Users will be advised that there are some daily routines that can trigger cravings, and suggested changes to those routines will be recommended. | Avoid cues that trigger urges to smoke. | BS7 (Advise on changing routines). | This section offers interaction, through users considering their day-to-day activities, and applying the tips to their problem situations. |

| 12. Users are asked to identify situations where they think they might smoke. Then, generate their own way of dealing with it. | Avoid cues that trigger urges to smoke. | BS1 (Facilitate barrier identification and problem solving); BS2 (Facilitate relapse prevention and coping). | More of a challenge, this activity will provide users with a chance to think about what they do already to help themselves stop smoking. Also, this gives a chance to engage more actively as users provide their own contribution. |

| 13. Users are asked to note down activities they might use to keep themselves busy, when they feel the urge to smoke. | Develop effective ways of distracting attention. | BS2 (Facilitate relapse prevention and coping). | Users engage with the webpage and write down activities, rather than just reading. |

| 14. Users are encouraged to use brisk exercise when they experience a craving. | Develop effective ways of distracting attention. | BS2 (Facilitate relapse prevention and coping). | This is brief, potentially very effective advice — ideally suited to a web context, providing valuable information with little time commitment. |

| 15. A section will explain the potential benefits of using glucose tablets to suppress cravings. | Develop effective ways of distracting attention. | BS2 (Facilitate relapse prevention and coping). | This advice provides another potential route to reduced cravings — creating the perception that there is lots on offer. This may reinforce the potential usefulness of the website. |

| 16. Users will be provided with advice and instructions about how tensing and relaxing areas of the body can reduce cravings. Audio will be used here. | Develop effective ways of distracting attention. | BS2 (Facilitate relapse prevention and coping); BS10 (Advise on conserving mental resources). | Again, this provides users with a skill they can take away from the website and use throughout the day. Coupled with a growing body of techniques this may increase engagement with the intervention through the perception of useful tools. |

| 17. Users are advised to conserve their mental energy. Depletion of resources and cravings are described. | Maximise levels of mental energy. | BS10 (Advise on conserving mental resources); RC6 (Provide information on withdrawal symptoms). | This section will provide participants with a positive message: that it is important to take time out, and make sure they look after themselves. Positive messages stemming from the website may reinforce both the active technique and regular engagement with the programme. |

| 18. Users are encouraged to attend to small things in their daily routine that may support their quit attempt. One such message is to try going to bed earlier than usual. | Maximise levels of mental energy/Avoid cues that trigger urges to smoke. | BS7 (Advise on changing routines); BS10 (Advise on conserving mental resources). | This is simple advice which can be expressed briefly, and may takes users a day further into their quit attempt, thus reducing the likelihood that they will smoke. |

| 19. Users will learn relaxation techniques. These will be presented through audio. | Maximise levels of mental energy/Develop effective ways of distracting attention. | BS2 (Facilitate relapse prevention and coping); BS10 (Advise on conserving mental resources). | The use of audio for this section increases the variety of media used on the website. Relaxation training also provides participants the opportunity to develop or learn a skill that they can take away from the website. |

| 20. There will be a detailed fully tailored section on medication advice, for those using medication with the website. | Make most effective use of medication. | BS2 (Facilitate relapse prevention and coping); BS3 (Facilitate action planning); A1 (Advise on stop-smoking medication); A3 (Adopt local procedures to enable users to obtain free medication). | This section will be highly tailored. This will increase the perception of detailed, individualized information. This is critical to sustain engagement. Use of medication is also highly likely to help with relapse prevention. |

| 21. Users will be provided with supportive messages of encouragement throughout the intervention. | Establish a rapport with website/Always provide rewarding experience. | BM2 (Boost motivation and self efficacy); RC1 (Build general rapport). | These messages will help to portray the website as supportive, and understanding. They will be provided both when a user is feeling low in confidence, and high in confidence (in the latter case they will be very brief). |

Intervention structure and content

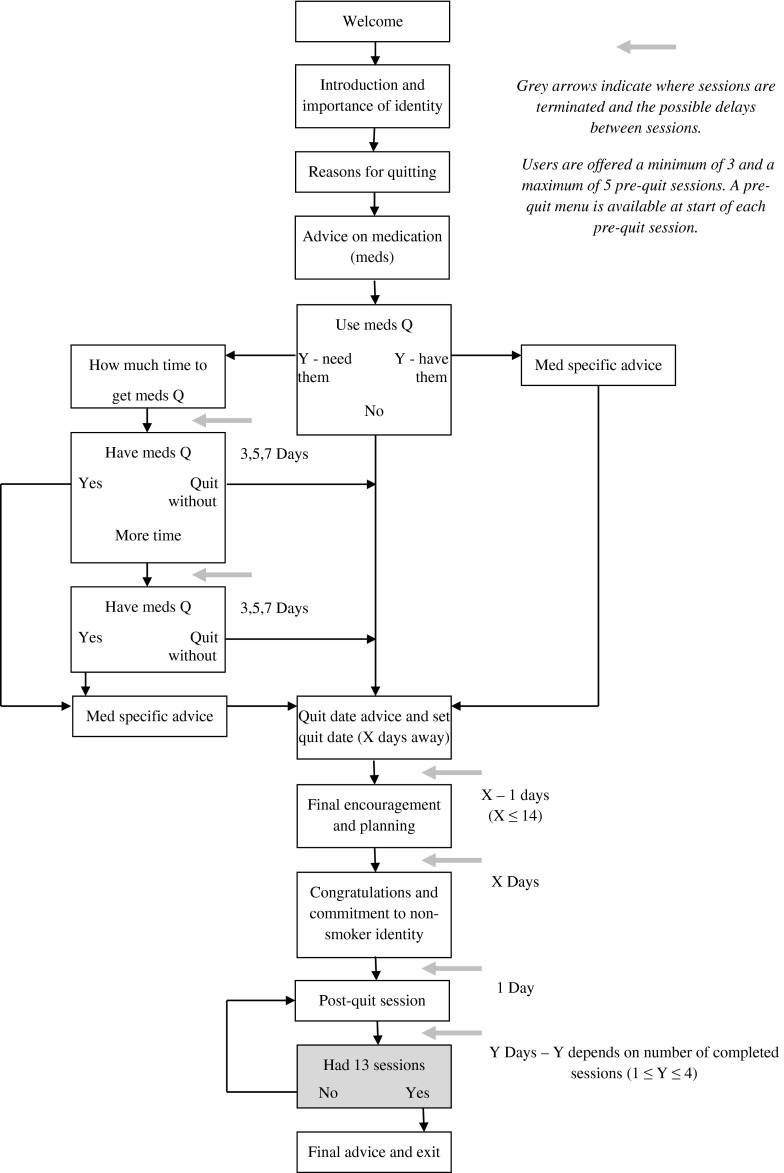

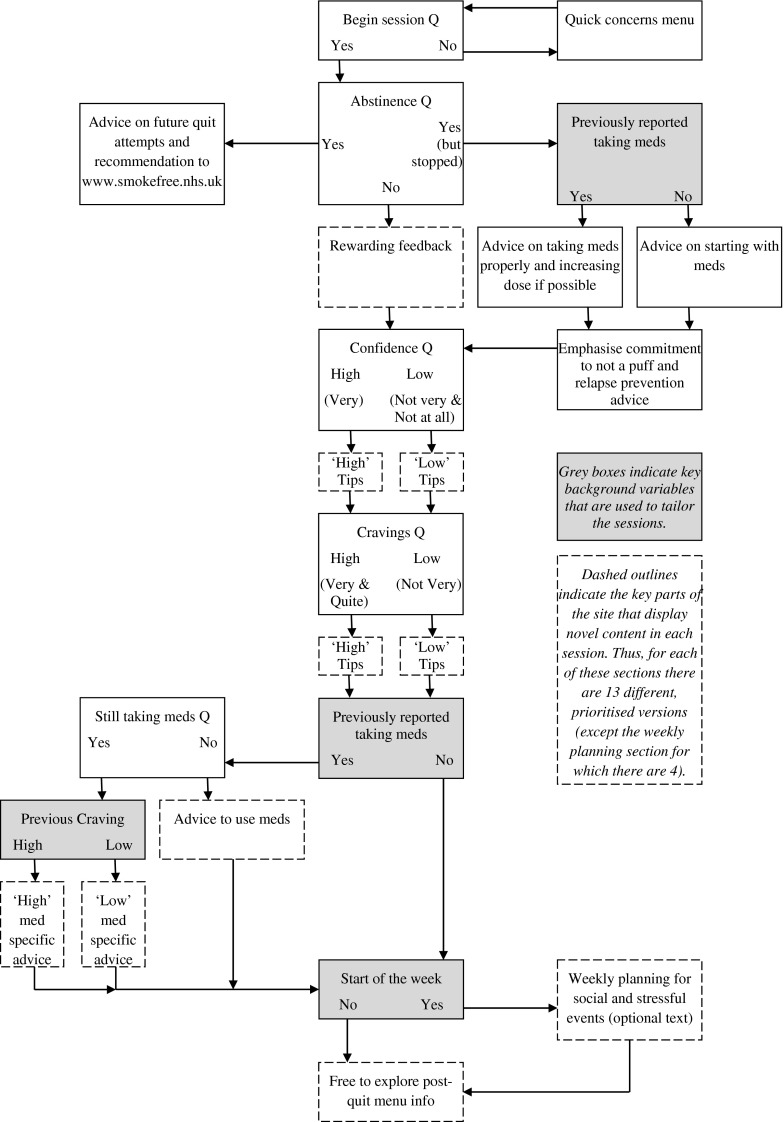

The programme will take users from preparation for the target quit date, to the quit date itself and then encourage them to report important information that the programme will use to help them overcome difficulties that they encounter. The pre-quit tailoring will be based on the following: reasons for quitting, intended use of medication, speed and success in obtaining medication, type of medication and quit date. The preparatory guidance will focus on the following: acquiring appropriate medication and using it optimally, making changes in routines to minimise difficulties and urges to smoke after the target quit date, developing specific coping strategies for when difficulties arise, and having clear expectations about the natures of those difficulties. Post-quit tailoring will be based on participants’ reports of: abstinence, urges to smoke, confidence in ability to remain abstinent, use of medication and anticipated frequency of stressful or social events. The guidance offered in response will involve specific advice on how to address these problems and plan to minimise their future occurrence. The overall website structure and the post-quit sessions are shown in a flow-chart (Fig. 1) and described in more detail in the following subsections.

Fig 1.

Flow chart of overall website structure. Flow chart of structure for all post-quit sessions

Sign-up and assessment

Participants will read information about the study, give consent, and then complete baseline measures.

Welcome-information and medication prompting

Participants will be welcomed to the intervention site (StopAdvisor), where they will be able to find out more about the website in general (including a screencast demonstration of the website’s structure). They will read about cravings and the brain, the importance of medication in reducing symptoms and regarding smoking as ‘not an option’, and the benefits of engaging in a behavioural support programme, i.e. our web intervention. Next, users will be asked to identify their reasons for quitting. They will then read about the different forms of medication and make a decision on how they will proceed with medication. If they need to get medication, they will be able to take as long as 2 weeks to obtain it. Once their chosen time has passed, they will receive an email enquiring whether they have their medication. The email will also ask them to log-in and set a quit date. If participants choose not to use medication, or already have their medication, then they will be immediately directed to the page where they can set their quit date.

Quit date selection, lead up to quit date

Participants will be given a 2- to 14-day window to set their quit date. They will be advised to allow a week to prepare effectively for their quit attempt and will also receive medication-specific advice. Once participants have set their quit date, they will be sent an automated email confirming their choice and recommending that they keep to their chosen date. On the day before, and on their quit date, they will be sent further emails inviting them back to the site to read about quit preparation techniques and information. Participants will have the chance to plan their last cigarette and request a supportive text message at the planned time. Also, they will receive information and advice intended to cover the following topics: withdrawal symptoms and the management of expectations; avoiding potential cues and triggers to urges; using social contacts and social support; avoiding high risk situations; the importance of abrupt cessation and commitment prompting.

Post quit date, week 1

Participants will be invited back to the website every day in the first week of their quit attempt. After signing in, they will have the option to address any quick concerns using a FAQ-style menu or to begin their personalised session. Participants beginning their session will be asked if they have smoked since their last visit. Those who say no will receive positive and encouraging feedback. Those who say they have had a slip will be directed to complete abstinence information. This information will repeat the rationale for the importance of the ‘not a puff’ rule. Those who report smoking as normal will be encouraged to reflect on what they have learnt from the experience, and then to have a break. Once they feel ready to try again, they will be encouraged to see a stop-smoking practitioner and recommended to visit www.smokefree.nhs.uk.

Participants who have avoided a full relapse will be asked about their confidence. Depending on their response, participants will be directed to pages on how to deal with low or high confidence. Both will provide supportive messages aimed at boosting their motivation and self-efficacy, although in the latter case the advice will be very brief. For those with low confidence, advice will also variously include the provision of normative information and a re-iteration of self-selected reasons for quitting.

Next, participants will be asked to rate the extent of their cravings. They will select from a number of options. Each option will take them to information about cravings, and importantly, how to reduce them. Techniques will be matched to the extent of the craving. If participants report low cravings they will be encouraged and informed that they are becoming less dependent and moving towards being non-smokers.

After the craving advice and tips, participants who elected to use medication will be asked if they are still using it. If participants are still using medication and also reported low cravings, they will be provided with positive, encouraging feedback, and a reiteration of why medication is important in supporting their quit attempt. If participants are still using medication but also reported high cravings, then they will receive a reminder on how to use their medication correctly in addition to the positive, encouraging feedback, and the reiteration of the importance of medication. If they have not been using medication they will read information about how they should be using it, and the importance of not only taking it, but using it correctly.

At the start of the first week, participants will then engage with a section on coping with risky situations, which includes the opportunity to re-commit to quitting and the offer of a supportive text message to be sent at times of highest risk. They will then come out of the ‘tunnel’ and be able to access information and parts of the site as they choose. The tunnelled sessions will be available every day throughout the first week.

Post quit date, weeks 2–4

Participants will be offered fewer personalised sessions (three in the second week, two in the third, and one in the fourth and final week).They will retain the option to login whenever they want and address any quick concerns. The structure of the sessions from week 2 to week 4 will be the same as week 1. However, the content will continue to vary; there will be a bank of 13 sets of corresponding advice for each possible response to every question. Consequently, there will be different information and advice in every session even if the person continually selected the same responses. The change in advice offered will reflect current circumstances. For example, if participants continue to report that they have not smoked, there will be a greater focus on their shift in identity — and how they are well on the way to becoming a non-smoker and all the benefits that includes. Similarly, the website will reflect the sustained reporting of a difficulty. For example, “We see that you have been feeling low in confidence on a number of occasions. Our team have seen many people who often feel low in confidence and go on to quit successfully”. The focus on new information, help, and tips is intended to keep participants coming back to the website, and participants will be told about how new information will be made available in every session.

At the end of every session after their quit date, users will have access to a personalised interactive menu. This menu will include sections on ‘Your Progress’, which will display days since their quit date, money saved and likely health benefits; ‘Stories’, which will include videos and text of ex-smokers discussing their experiences since quitting; ‘Music’, ‘Gallery’, ‘Facebook’, ‘Relaxation’, ‘FAQs’ and ‘Links’.

DISCUSSION

We have described the development of an interactive smoking cessation website designed to be attractive and effective across the social spectrum. It was informed by a broad motivational theory (PRIME), empirical evidence, web-design expertise, and user-testing. During development, we identified 19 theoretical propositions, 33 evidence- or theory-based BCTs, 26 web-design principles and nine principles from user-testing. These were synthesised and implemented to create the website, ‘StopAdvisor’.

Behaviour change interventions often suffer from an insufficient reporting of content in their published evaluations, which leaves researchers unclear as to exactly what it was that made an intervention effective [36]. In the context of the significant heterogeneity of outcome associated with internet-based smoking cessation interventions such inadequate reporting is of particular concern [1–3]. The current paper demonstrates the feasibility of developing an internet-based smoking cessation intervention through the systematic and transparent application of theory, evidence, web-design expertise and user-testing. This approach should be equally applicable to the development of interventions targeting other health behaviours.

The next stage is evaluation. We have recently conducted a quantitative pilot study that demonstrated StopAdvisor to have sufficiently promising efficacy and usability to warrant a full-scale evaluation of the website [37]. We are currently running a randomised controlled trial that aims to evaluate the efficacy of StopAdvisor and whether any identified efficacy translates across the social spectrum (ISRCTN99820519). It is a two-arm trial, with participants randomised to the offer of StopAdvisor or a static website that presents brief and standard advice and followed up for up to 7 months after enrolment. Following completion of the trial we will use a ‘fractionated factorial design’ [5] to build incrementally on whatever level of effectiveness is achieved, by adding or substituting component BCTs. These will be selected on the basis of analysis of smokers’ interactions with the prototype version of StopAdvisor, a theoretical analysis and initial experimental testing. The use of LifeGuide to develop StopAdvisor should facilitate this process.

We believe this to be the first study to develop and trial an internet-based smoking cessation intervention specifically intended to be attractive across the social spectrum. Since disadvantaged groups are typically less responsive to internet interventions, we engaged with these smokers early in the website development and modified content according to the qualitative feedback we received. Using LifeGuide software facilitated this process, allowing modifications at any time without the requirement for programmers.

The main limitation to the systematic and transparent reporting of the development of this intervention relates to researcher judgment. In such a large and complex intervention some decisions, both about what to include in the intervention and what to report upon here, will have been made without being documented. We hope to have mitigated this effect by keeping careful records of the development process and reporting the content in detail here.

CONCLUSION

It is feasible to develop an internet-based smoking cessation intervention through the systematic application of theory, evidence, web-design expertise and user-testing. Moreover, it is possible to report transparently on the development process and resulting content. This transparency combined with the use of an open-source development platform should provide a basis for multi-phase optimisation contributing to an ‘incremental technology’ of behaviour change.

Footnotes

Implications

Policy: It is feasible to invest in intervention development that systematically applies theory, evidence, expertise and user-engagement.

Research: Transparency and an open-source development platform should contribute to an ‘incremental technology’ of behaviour change.

Practice: It is possible to report transparently on a systematic development process and the resulting content.

References

- 1.Civljak M, Sheikh A, Stead Lindsay F, Car J. Internet-based interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (9). http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD007078/frame.html; 2010 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Myung SK, McDonnell DD, Kazinets G, Seo HG, Moskowitz JM. Effects of web- and computer-based smoking cessation programs meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(10):929–937. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shahab L, McEwen A. Online support for smoking cessation: a systematic review of the literature. Addiction. 2009;104(11):1792–1804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Webb LT, Joseph J, Yardley L, Michie S. Using the Internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12(1):e4. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins LM, Baker TB, Mermelstein RJ, et al. The multiphase optimization strategy for engineering effective tobacco use interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41(2):208–226. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9253-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organisation (2009). WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic.

- 7.Kuehn BM. Updated US smoking cessation guideline advises counseling, combining therapies. JAMA. 2008;299(23):2736–2736. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.23.2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.West R, Fidler J. Key findings from the Smoking Toolkit Study. www.smokinginengland.info; 2010.

- 9.Stead LF, Perera R, Lancaster T. Telephone counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD002850. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002850.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saul JE, Schillo BA, Evered S, et al. Impact of a statewide Internet-based tobacco cessation intervention. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9(3):e28. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.4.e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graham AL, Cobb NK, Raymond L, Sill S, Young J. Effectiveness of an Internet-based worksite smoking cessation intervention at 12 months. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49(8):821–828. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3180d09e6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swartz LHG, Noell JW, Schroeder SW, Ary DV. A randomised control study of a fully automated internet based smoking cessation programme. Tob Control. 2006;15(1):7–12. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.006189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hare J, Osmond A, Yang Y, et al. LifeGuide: A platform for performing web-based behavioural interventions. Proceedings of the WebSci'09: Society On-Line, 18–20 March 2009, Athens, Greece; 2009.

- 14.Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, et al. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: Best practices and recommendations from the NIH behavior change consortium. Health Psychol. 2004;23(5):443–451. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stoddard JL, Augustson EM. Smokers who use internet and smokers who don't: data from the Health Information and National Trends Survey (HINTS) Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8(Suppl 1):S77–S85. doi: 10.1080/14622200601039147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kotz D, West R. Explaining the social gradient in smoking cessation: it's not in the trying, but in the succeeding. Tob Control. 2009;18(1):43–46. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.025981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilmour JA. Reducing disparities in the access and use of Internet health information. A discussion paper. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(7):1270–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glasgow RE. eHealth evaluation and dissemination research. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(5, Supplement):S119–S126. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.West R. The multiple facets of cigarette addiction and what they mean for encouraging and helping smokers to stop. COPD. 2009;6(4):277–283. doi: 10.1080/15412550903049181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michie S, Hyder N, Walia A, West R. Development of a taxonomy of behaviour change techniques used in individual behavioural support for smoking cessation. Addict Behav. 2011;36(4):315–319. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.West R, Evans A, Michie S. Behavior change techniques used in group-based behavioral support by the english stop-smoking services and preliminary assessment of association with short-term quit outcomes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(12):1316–1320. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michie S, Churchill S, West R. Identifying evidence-based competences required to deliver behavioural support for smoking cessation. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41(1):59-70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.West R, Walia A, Hyder N, Shahab L, Michie S. Behavior change techniques used by the English Stop Smoking Services and their associations with short-term quit outcomes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(7):742–747. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Godfrey C, Parrott S, Coleman T, Pound E. The cost-effectiveness of the English smoking treatment services: evidence from practice. Addiction. 2005;100:70–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brose LS, West R, McDermott MS, Fidler J, Croghan E, McEwen A. What makes for an effective Stop Smoking Service? Thorax. 2011;66:924–926. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Everitt HA, Moss-Morris RE, Sibelli A, et al. Management of irritable bowel syndrome in primary care: feasibility randomised controlled trial of mebeverine, methylcellulose, placebo and a patient self-management cognitive behavioural therapy website. (MIBS trial). BMC Gastroenterol. Nov 18 2010; 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.McDermott L, Yardley L, Little P, Ashworth M, Gulliford M, Team eR. Developing a computer delivered, theory based intervention for guideline implementation in general practice. BMC Fam Prac. Nov 18 2010;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Yardley L, Nyman SR. Internet provision of tailored advice on falls prevention activities for older people: a randomized controlled evaluation. Heal Promot Int. 2007;22(2):122–128. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dam007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yardley L, Joseph J, Michie S, Weal M, Wills G, Little P. Evaluation of a Web-based intervention providing tailored advice for self-management of minor respiratory symptoms: exploratory randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12(4):97–108. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yardley L, Miller S, Teasdale E, Little P, Team P. Using mixed methods to design a web-based behavioural intervention to reduce transmission of colds and flu. J Heal Psychol. 2011;16(2):353–364. doi: 10.1177/1359105310377538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strecher VJ, Shiffman S, West R. Randomized controlled trial of a web-based computer-tailored smoking cessation program as a supplement to nicotine patch therapy. Addiction. 2005;100(5):682–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morrison LG, Yardley L, Powell J, Michie S. What design features are used in effective e-Health interventions? a review using techniques from critical interpretive synthesis. J Telemed eHealth. 2012;18(2):137-144. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Danaher BG, Boles SM, Akers L, Gordon JS, Severson HH. Defining participant exposure measures in Web-based health behavior change programs. J Med Internet Res. Jul–Sep 2006; 8(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Office for National Statistics. The National Statistics Socio-economic Classification: user manual. 2005.

- 35.Yardley L, Morrison L, Andreou P, Joseph J, Little P. Understanding reactions to an internet-delivered health-care intervention: accommodating user preferences for information provision. BMC Med Informat Decis Making. 2010;10(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-10-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michie S, Abraham C. Advancing the science of behaviour change: a plea for scientific reporting. Addiction. 2008;103(9):1409–1410. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown J, Michie S, Geraghty A, et al. A pilot study of StopAdvisor: a theory-based interactive internet-based smoking cessation intervention aimed across the social spectrum. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]