ABSTRACT

Currently integrating mental health, substance abuse, and health behavior into Patient-Centered Medical Homes (PCMH) is being advocated with increasing frequency. There are no current reports describing efforts to accomplish this. A theory-based project was developed to integrate mental health, substance abuse, and health behavior services into the fabric and culture of an NCQA-certified level-three PCMH using funding from the Vermont legislature. A mixed methods case report of data from the first 34 months reviews planning, development, implementation, care model, information technology (IT), and data collection, and reports results using the elements of a RE-AIM framework. Early accomplishment of most RE-AIM dimensions is observed. Implementation remains a struggle, specifically the questions of role responsibilities, form, and financing. This effort is a successful pilot implementation of the Primary Care Behavioral Health (PCBH) model in the PCMH with the potential for dissemination toward additional implementation and a model for a comparative effectiveness trial.

KEYWORDS: Primary, Care, Behavioral, Health, Integration, PCMH, RE-AIM

BACKGROUND

The Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) is conceived as a method for delivering whole person care to the entire panel of patients attending a primary care practice [1, 2]. As initially defined, it only indirectly acknowledged mental health, substance abuse, and health behavior issues that are part of patient presentation or how such needs are to be addressed. This has been perceived by some as a structural shortcoming of the model, given that primary care has been noted for some 30 years as the de facto mental health and substance abuse system [3, 4].

To briefly summarize this position: the Primary Care Behavioral Health (PCBH) and health behavior services of our health care system do not meet the needs of most US citizens. In a summary of the literature, Kessler and Stafford found that 43–60 % of patients with psychological problems are treated solely in primary medicine, while only 17–20 % of these patients are treated in the specialty mental health care system [4]. Despite the concentration of patients needing treatment that present in primary care, a survey of 6,600 primary care physicians found that quality mental health services were the most difficult subspecialty to access [5]. Availability of effective behavioral health services in PCMH settings is an important public health issue, as demonstrated by additional findings that show 50 %–90 % of primary care referrals that are made to out-of-office mental health practitioners fail to result in a follow up appointment [4].

The past 20 years have witnessed an evolution towards integration of mental health into primary care. It is now a goal of the American Academy of Family Physicians [6] to integrate behavioral health into the core principles of the PCMH [7]. Kessler et al. have recently completed a survey of all National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA)-certified PCMH. Findings observe that less than 40 % of respondent practices have any mental health, substance abuse, or health behavior clinicians as part of the practice and less than a third use evidence-based health behavior protocols. The majority of these noted that lack of knowledge about how to integrate such services into primary care was a major obstacle (Kessler et al. manuscript under review). As noted by Green, PCBH is a clinical field alive with ongoing change activities, allowing it to serve as a laboratory for studying effective and rapid change processes. Interestingly, these arguments have rarely focused on the influence of health behaviors on health status and functioning, or on the empirical literature supporting the efficacy and sometimes the effectiveness of psychological and behavioral interventions on influencing the outcomes of multiple acute and chronic medical conditions in the primary care settings (Kessler et al., under review). In disparate settings around the United States and other countries, there has been recognition that primary care reform that does not include responses to mental health, substance abuse, and health behavior services limits the potential effectiveness of the proposed changes [1].

In Vermont, such recognition came from an unusual source—the Vermont legislature. As part of its initiative to reform health care, in 2006, the legislature created the Vermont Blueprint for Health, an effort to pilot implementation of PCMH in Vermont primary care practices. One of the three pilot sites selected for implementation was Aesculapius Medical Center (Aesculapius), an internal medicine practice part of Fletcher Allen Health Care (FAHC), the academic health center associated with the University of Vermont College of Medicine. In the second year of operation of the Aesculapius pilot, the legislature created funding to integrate mental health and substance abuse services (but not specifically health behavior services, referring to empirically derived behavioral interventions that either enhance patient participation in their health care, enhance health and medical outcomes, or are first line treatments of medical problems) into four PCMH sites. The timing of this support was fortuitous. FAHC had some history of mental health services in some of its primary care practices. Planning for integrating mental health and substance abuse services into FAHC primary care settings had been in process prior to the legislative effort. Financial concerns limited planning. The legislature’s targeted funding supported integration of mental health, substance abuse, and psychological interventions as part of acute and chronic medical treatments into the Aesculapius PCMH pilot.

Aesculapius is a FAHC internal medicine practice with nine physicians and three nurse practitioners serving a panel of approximately 16,000 patients. The practice is located in a suburban community of 17,900 residents. Figure 1 illustrates payer mix, with a preponderance of practice patients holding commercial insurance, 30 % Medicare, and a much smaller portion (3.8 %) Medicaid. It is about 10 min from the medical school and hospital campus. It was selected to be an initial Blueprint for Health pilot because when combined with a single provider private practice nearby, the two sites met the criteria of providing care for 20,000 patient lives and Aesculapius demonstrated readiness to begin the PCMH implementation process. It was selected as the site for the mental health and substance abuse project because of recognized need, practice interest, and availability of a senior clinician experienced in such integrated models of care.

Fig 1.

Payer mix for practice and PCBH-only patients

Initial program development and implementation process

After approval from FAHC administration including the chair of Primary Care Internal Medicine, a work team was formed to initiate, recruit, and implement the project. It consisted of the FAHC Director of Primary Care, the Aesculapius physician lead, the practice office manager, and the University of Vermont-based psychologist who was the initiator of primary care-based behavioral health services and who would become clinical supervisor of the project. Until the PCBH clinician recruitment began, those four individuals designed and implemented the project with minimal involvement of other clinic medical or administrative staff. Core decisions that were made by this group included the location of the clinician office, the support staff for the position, and referral initiation. Functionally most decisions about operations, clinical issues, and administrative support were made post hoc. The practice medical director met with the medical staff a total of three times, once to introduce the function of the PCBH model, once to discuss process, and once to follow up after process initiation to address concerns.

The model

Most of the initial planning concerning the clinical model was provided by Rodger Kessler, PhD based on his 15 years of experience in health psychology services at a different FAHC primary care practice. The conceptual model was drawn from two sources. The first was an adaptation of Strosahl and Robinson’s PCBH Consultant model [8]. That model provided the focus on modeling session length, time frame, scope of patient care, and administrative processes to the clinical and operational functioning of the primary care practice. The second was to adopt Peek’s Three World Model applied to the integration of mental health in primary care [9]. Peek suggests the clinical care is simultaneously a clinical, operational, and financial intervention. Within a practice, different people in different positions focus on more or less of each of those aspects of practice functioning. He suggests that successful innovation within primary care occurs when those different elements are aligned and when there is interaction among the different job functions and perspectives. The resulting model was an adaptation of the elements of the PCBH clinical model, focusing on the interaction of the clinical, operational, and financial dimensions of practice and tailoring the intervention to the existing [medical center name] practice. Table 1 illustrates the core elements of the model.

Table 1.

FAHC primary care behavioral health intervention components

| Clinical | • Full-time primary care behavioral health clinician (per 7,500 patient panel (Hunter et al. 2009)) with clinical and care management responsibilities |

| • Clinician availability for personal, face to face introductions (“warm handoffs”) and consultation | |

| • Brief evidence-supported treatment interventions | |

| • Intensive training of primary care behavioral health clinicians, using treatment protocols for a broad range of psychological and medical problems amenable to behavioral health treatment | |

| • Population (panel)-based care using measurement-based, stepped treatment and other resources | |

| Operational | • Screening for behavioral health and physician decision support seamlessly integrated into EHR |

| • Practice reengineering of operational processes, e.g., “warm handoffs” | |

| • Automated referral and patient scheduling | |

| • Training physicians and staff in behavioral care procedures | |

| • Appointment frequency and interval consistent with primary care | |

| • Shared transparent EHR with two-way notes and access to information | |

| • Care management to coordinate referrals and information to/from specialty care as needed | |

| Financial | • Brief interventions over brief time frames |

| • Coordination of services and finances to optimize sustainability | |

| • Regular reports of performance, RVU, and financial data |

Implementation

We recruited the lead author, a licensed Independent Social Worker (LICSW) to fill the position of behavioral health clinician. Previously, she had experience working in a community mental health setting providing mental health assessment and treatment for children, adolescents, and adults. She had no previous primary care experience or specific training in health behavior interventions. She was recruited because she had the potential to adapt to the setting and learn; had enthusiasm, understanding, and rationale for the PCBH model; and was able to work within our available financial parameters. Implementation of a new clinical provider to a practice, regardless of their specialty, takes planning, communication, and education. When adding a PCBH clinician to a well-established medical practice with no history of any behavioral health services practice, the importance of communication and education of staff and providers cannot be overstated but can easily be underprovided.

The creation of the physical environment to support the PCBH clinician was not a difficult one. The PCBH provider has fewer operational needs than an MD or a midlevel medical provider. Space, supplies, and support staff needs are minimal. Necessary support like schedulers, phone receptionists, and billers were existing staff. Few supplies, other than basic office phone and computer supplies and educational materials, were needed. Comfortable, private office/patient care space was available adjacent to another physician’s office. Some patient sessions have been held in regular exam rooms as needed. Providing a comfortable office space adjacent to other providers in the practice was a communication within the practice that showed a level of respect and acceptance by the providers and the leaders of the practice that the PCBH clinician is a member of the medical staff. Often, when psychologists and other behavioral health clinicians practice in primary care lack of appropriate space is an issue.

A more challenging component of PCBH implementation is the change in culture, process, and communication, and clearly understanding clinic staff and provider education needs. The outline of the PCBH role in the practice was shared with medical staff, and in retrospect, to a lesser degree with office staff. We attempted to identify patient flow, referral, and billing processes within the practice. We actively addressed the typically unspoken concerns of the staff about the stigma that can be associated with and applied to patients who seek mental health and substance abuse care and the feelings that this evokes in the staff. Staff additionally identified individual feelings of anger and resentment regarding extra workload for BH-specific processes, such as insurance authorizations and preappointment paperwork, which did not fall under typical PCP administrative work, were initially confusing or unclear to them and simply took more time. Directed communication and education of staff along with open dialogue to address their questions and concerns was our strategy, and it is an ongoing improvement process.

Implementing the intervention

Responsibilities were outlined in three primary areas—clinical, operational, and financial. Clinically, the PCBH clinician is responsible for providing consultation, brief cognitive behavioral assessment, short-term intervention, and referral for community-based services for more intensive or unavailable specialty care. From the beginning of implementation of the EPIC-based electronic record, all patient records, referrals, and communication were a transparent part of the electronic medical record (EHR) documentation and process flow. All patients are screened at the initial PCBH appointment using PHQ-9 [10] for depression, GAD-7 for anxiety [11], and Audit [12] for assessment of alcohol use. Screening is currently in paper format and given to patients at check-in and completed by patients in the waiting room prior to the appointment time. Screens are completed with the PCBH clinician for patients who are unable to complete them due to literacy, vision, comprehension, or other issues. These issues will be further discussed shortly. Clinical interventions include self-monitoring, cognitive restructuring, relaxation training, and problem-solving techniques. Outcomes monitored include improvements in initial screening scores, relevant clinical biometrics, such as A1C, LDL, and BMI, as well as patient treatment initiation, no show rates, and patient and provider satisfaction with services.

Operationally for collaborative treatment to occur, there has to be agreement, development, and understanding of clinical and operational processes across the clinic. Initially we educated the medical providers regarding the array of health conditions that have behavioral components (health behavior) in addition to traditional mental health and substance abuse conditions, and to agree on treatment approaches to ensure appropriate referral. Throughout startup, we identified and defined processes to support scheduling, check–in, and billing procedures that were understood by staff and easy for patients. Referral forms for behavioral health services were initially paper forms and then transferred into regular orders within the EHR, and delivered electronically to scheduling support staff for immediate scheduling both after initial referral and for behavioral follow-up. There are shared treatment notes as well as formal and informal face-to-face meeting time.

Financially the startup of this project would not have occurred in its current fashion without grant support. We recognized that in order to make this a viable and sustainable venture the PCBH clinician needed to support 80 % of their salary through direct patient care receipts. This would be accomplished by having not only the traditional 50-min assessment visit but also by 25-min follow-up visits, thus allowing more visits per day and taking advantage of contractual enhancements that incentivize brief visits through increased reimbursements. The additional 20 % of the PCBH clinician salary is supported by the increased per member per month (PMPM) payments associated with achieving Level 3 PCMH certification from the NCQA. This support is for currently nonreimbursed indirect patient care supervision, program development, and clinical research.

Measurement and information technology

Not only is PCBH an emerging and evolving model of care, it is embedded within an emerging primary care reengineering, that is, the PCMH, and newly evolving measurement and information technology systems. It has been both an advantage and a struggle. The PCBH project began with paper records and rapidly became engaged in the emergence of the electronic health record. Initially, there was no planning for PCBH assessment and note writing or information sharing within the EHR. In general, health systems and primary care organizations develop and implement EHR’s with limited resources and a focus on the core issues of primary care. Multiple hours of effort were required to develop EHR parity and bidirectional communication within primary care with no access limitation. Resolving certain professional concerns about confidentiality were worked through and all steps were signed off by our regulators prior to implementation. EHR’s are not designed or resourced to easily include the needs of PCBH in primary care practices particularly in the early phases of development. Yet it is axiomatic in EHR development for any specialty that retrofitting is more difficult, more timely, and more expensive than inclusion upfront. Therefore, the upfront hours pushing our way to the EHR table are a crucial element of program development. A subset of the technology issue is screening for behavioral health issues. A fuller discussion of the wide range of screening issues can be found in other publications [13].

The ability to capture data from patients concerning mental health, substance abuse, and health behavior in real time, and provide that summarized data to be available during the patient visit is closer but not yet generally achieved in our setting or in general primary care. It has taken our system 5 years to get to the place that when this paper is in print, point of contact screening will have become a regular part of patient and practice flow, in an electronic version with decision support to assist patient physician care. At present, data is collected post-referral of the PCBH clinician with retrospective physician review. We are still inefficient and emerging in this area, clinically, operationally, and financially. With the emergence of the NIH core measures, this entire issue will be both more prominent in the field with a broader focus on overall health assessment [14].

RESULTS

All data reported are de-identified reports generated from the FAHC database and covers the period from February 2009 to December 2011.

Reach

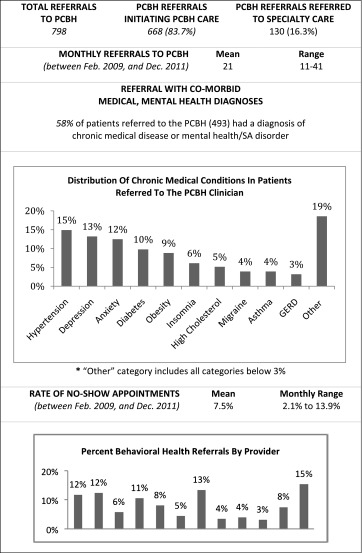

Table 2 displays referrals, treatment initiation, and treatment attendance. There were 798 referrals in the target time period. Fifty-eight percent of those referred had comorbid medical diagnoses in addition to a mental health or substance abuse diagnosis. Of those patients referred to the PCBH clinician, 83.7 % initiated treatment and 16.3 % were referred to specialty care. No show rates were 7.5 % on average. Figure 1 illustrates the differences in payer mix differences between practice-wide patients and PCBH patients. For the PCBH referrals, commercial insurance is the primary payer. Medicaid was a larger payer (13.5 %) and Medicare a smaller one (8.2 %) than the general practice (3.8 % and 27.6 %, respectively).

Table 2.

PCBH clinician referrals, initiation, and patient attendance

Effectiveness

Providers consistently refer patients, although frequency varies (Table 2). Patients generally complete screening questionnaires (74 %), and 44 % of respondents indicated moderate to severe depression and 46 % anxiety (see Table 3). Sixteen percent of respondents endorsed moderate to severe alcohol use problems. There was improvement in ratings of functioning 6 months after treatment initiation (see Table 4). Table 4 also illustrates that 61.1 % of patients reported initiating treatment because the services were part of the primary care practice.

Table 3.

Initial behavioral health screening completion and results

| Screening completion (% of all screens administered) | ||||

| Completed | Partially completed | Not screened | Refused | |

| 74 % | 4 % | 15 % | 7 % | |

| Scoring distribution (of completed screens) | ||||

| PHQ-9 | ||||

| Negative | Mild depression | Moderate depression | Moderately severe depression | Severe depression |

| 24 % | 32 % | 20 % | 15 % | 9 % |

| GAD-7 | ||||

| Negative | Mild anxiety | Moderate anxiety | Severe anxiety | |

| 23 % | 31 % | 25 % | 21 % | |

| AUDIT | ||||

| Negative | Moderate problem | Severe problem | ||

| 84 % | 11 % | 5 % | ||

Table 4.

Follow-up survey completion and results

| Completion of resurvey (of those that completed that part of the initial survey) | ||

| PHQ-9 | GAD-7 | AUDIT |

| 55 % (122) | 56 % (67) | 55 % (63) |

| Mean change in follow-up tests: | ||

| PHQ-9 | GAD-7 | AUDIT |

| −4.1 | −3.73 | −0.4 |

| % of patients that attended PCBH appointment because it was located in the primary care office: 61.6 % | ||

Adoption

All physicians and providers in the practice have referred patients. The practice has consistently made improvements to enhance the service such as generating support staff, including the PCBH clinician in practice process changes, and practice engaging in integrated care-oriented practice-based research and consideration of a panel-based obesity protocol.

Implementation

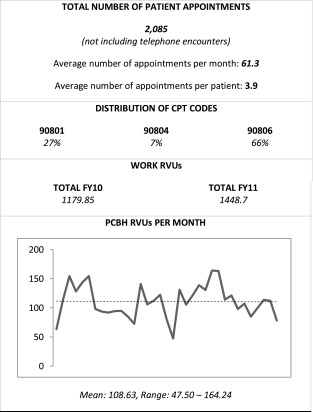

As noted in Table 2, patients were referred at an average rate of 21 referrals per month. Over a 34-month period, the PCBH clinician generated 2,085 appointments, not including telephone encounters, and patients were seen an average of 3.9 times (Table 5). Telephone encounters were minimal and primarily used for care coordination. The care model remains referral-based rather than population-based. Visit lengths remain primarily outside of the model. IT implementation and data reports remain inconsistent. Use of operational processes for referral, scheduling, EHR, and billing procedures is consistent.

Table 5.

Behavioral health clinician utilization

Maintenance

Patient reports suggest clinical improvement 6 months after treatment initiation. Initiation rates and attendance rates remain consistent and high. Over 2 years post-initiation, the project is thriving and changing. It is regularly discussed throughout the organization. Recently a position was developed and funded to direct PCBH and implement the model in all primary care practices. While the business model is constantly evaluated, there is clear potential for financial sustainability.

DISCUSSION

It appears that health care reform, particularly primary care reform, views behavioral health and health behavior as integral parts of the change even as there is struggle about what to do with it. At the regulatory, professional organization, NIH announcement level, there is increasing focus and attention. However, as we know, the devil is in the details, and the details are just in early phases of development.

Stepping back, it is not surprising that the initiative is located in Vermont. Vermont is an active state in health care reform and that fact has influenced the ability to develop this project. We would characterize our effort as successful, moving from pilot project to early maturity suffering from its novelty and high expectations. Ours is an implementation, theory grounded, with limited operational principles to rely upon.

That noted, we have successfully demonstrated early accomplishment of most RE-AIM dimensions:

Referral rates are higher practice-wide than any reported medical home project in Vermont, and treatment initiation rates after referral are higher than reported in the published literature. Limited data demonstrates improvement in ratings of functioning 6 months after initiation.

All physicians and providers in the practice have referred patients at a consistent frequency, although there is between-provider variation. The model has been subsequently implemented at another primary care setting in our academic health center and we are recruiting for another implementation. At that point, there will be four of nine primary care sites that have implemented the model, and all others have expressed interest.

There is limited and mixed implementation data. Referrals have been generally consistent. The care model remains referral-based rather than population-based. This leaves referral and access up to physician clinical judgment which has not historically had high levels of identification. In addition, the future of health care is moving towards evidence-supported panel-based care and away from referral-based models of care. Visit times remain outside of the model. IT implementation and data reports remain inconsistent. Use of consistent operational processes for referral, scheduling, use of EHR, and billing procedures is consistent. The program maintains and is growing.

We continue to struggle with implementation. The question of role responsibilities, form, and financing of behavioral health and health behavior has not yet been answered at the national, regional, and at most state levels. Certainly in our practice and system of care, we continue to struggle with each of those issues and essentially invent and test our responses. Results of the test are encouraging beyond the RE-AIM assessment. There is the beginning of a shift from a mental health service located in primary care to a core element of the primary care practice. There is recognition, if not action, that a greater focus on health behavior needs to occur. The service is carved into the medical budget. There has been and continues to be dissemination of the effort to other practices, which implementations benefit from lessons learned in this implementation. Insurers are aware of and are discussing how our work fits into their business and clinical models.

The business case

The business case for the integration of behavioral health into primary care is an invention. Since this is a new model of both delivering and financing care, the old methods of evaluating the financial outcomes of such a venture are not easily translatable. The lack of benchmarks, let alone agreed upon benchmarks to evaluate financial viability, is a barrier. This model of integrated care is consistent with the regular flow of a primary care practice with shorter visits, briefer treatment episodes depending on function, and team care. This allows for a higher volume of patients than in specialty care models and enhances the potential return on investment to include overall health status and utilization. However, the technology of financial modeling and of metric development has not caught up to the clinical and operational model development.

Earlier Peek’s reference to the importance of behavioral health’s attention to the interconnectedness of the clinical, operational, and financial dimensions of care was observed. We recognize that for the program to mature, it is our task to craft a business plan demonstrating the efficiency of the model in responding to each of Peek’s dimensions.

While each clinic will make specific adaptations to fit their needs, there is a set of observations that may well generalize the effect of the implementation and thus the financial model. We started with insufficient process improvement. A formal process improvement project, addressing the multiple issues inherent in establishment of such a project, will anticipate and respond to issues that were left unattended which will be more difficult to attend to later. All staff and providers need to begin implementation with a clear understanding of the intended model of care. The care model drives the business case. Without communication and education regarding the potential capacity of the PCBH clinician’s role, it can be easy for primary care physicians to limit referrals to those patients with primary presentations of mental health symptoms and not take advantage of the opportunity for collaborative treatment of medical disease. Education and communication are necessary but not sufficient. Disease protocols should be negotiated at the beginning of the practice. If there is a focus on panel-based management, with health behavior and behavioral health as active components, then that should be engaged rapidly or else the referral model is reinforced producing constricted potential. The PCBH program and clinician need to be active parts of emerging EHR’s. Both for communication and quality improvement, data access and use are crucial. In EHR systems, doing this at the beginning of implementation gets things accomplished more rapidly and with better system flow than retrospective retooling.

Limitations

This is a report of the implementation of a single PCBH model within a single PCMH practice within a single state. The state has an innovative and creative health care system and a history of responding to mental health and substance abuse issues. Data suggests that in this implementation, substance abuse identification and intervention may be underidentified and undertreated. Despite referral of patients with high frequency of medical issues amenable to evidence-based behavioral interventions, most referrals are for anxiety and depression and there is, thus far, a minimum of either alcohol or substance abuse or referral for health behavior and lifestyle modification issues. Like other Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine interventions, sufficient training and exposure has not yet been successful at changing the cultural view of what a behavioral health clinician does. This situation parallels findings from a national survey of NCQA PCMH’s that found that both health behavior and substance abuse organization and clinical care were highly infrequent in comparison to mental health issues (Kessler et al. in review).

The implementation is not yet mature and there is only partial fidelity to the intended model. Part of that is evolutionary, part limited implementation. Because of ongoing payer issues, concerning what services are reimbursed and for how much as well as PCBH not yet being an active element of health care financial reform, the intervention is dependent on mental health diagnoses and codes even when the treatment is for a medical problem. There is still a heavy reliance on traditional 45–50-min length of visit despite the model’s focus on briefer interventions. Barriers to that change exist on both the behavioral health and medical side. If a behavioral health clinician trained in a 50-min hour, it is difficult to change. Unfamiliarity with brief evidence-supported interventions is an obstacle on both the behavioral health and medical side. Lack of awareness of the effectiveness of the model limits institutional pursuit. Lastly, team care is a new construct in primary care and while it is beginning, it will take time to include PCBH in the breadth of possibility. The intervention is still a referral-based model although we are transitioning to panel-based care which will be data driven rather than referral driven.

IT development is more advanced than in many locations but still lags behind development on the medical side. Regular data reports lag and we are only in the initial stages of collecting cost data. Preimplementation process improvement was limited and our knowledge and use of this technology has advanced. Our ability to assess RE-AIM dimensions is post hoc and limited.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite limitations, some of which have been remedied in subsequent implementation while others are still in various stages of development, we consider this effort to be a successful pilot implementation with the potential to mature and a source of dissemination toward additional implementations. We have implemented a theory-driven model of behavioral health in a level three NCQA-certified PCMH. The service has a high level of acceptability to patients and providers. Rates of treatment initiation and treatment attendance are higher than previously reported. Limited data suggested that there are clinical improvements, at least in behavioral health ratings, 6 months after treatment initiation. There is regular transparent bidirectional use of the electronic health record and PCBH issues are part of ongoing IT development. The model and service have been sufficiently compelling that we have initiated another implementation and are recruiting for yet another installation. Financially we are breaking even, and there is the potential for financial sustainability. We have demonstrated that a behavioral health and, hopefully, a health behavior presence as part of a PCMH is viable, useful to patients and providers, valued organizationally, and sustainable.

Footnotes

Implications

Practice: Primary care should continue to be the focus of efforts to improve behavioral healthcare. It is not only the largest provider of behavioral and behavioral health services, but is also open and amenable to the presence of psychology and social work. PCBH intervention requires a unique implementation model and training techniques in the model. PCBH is not the same as mental health, substance abuse, and health behavior practice outside of primary care.

Policy: PCBH should be considered an important tool in responding to public health need. Provision of behavioral health and health behavior services within primary care may result in increased access to services and higher rates of treatment initiation.

Research: This case study should generate a larger trial with diverse practice settings and clinical populations. The information in this case example represents pilot data that merits a larger, RE-AIM-focused implementation trial and comparative effectiveness trial evaluating the PCBH model with other models of collaborative care.

References

- 1.Rosenthal TC. The medical home: growing eidence to support a new approach to primary care. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2008;21(5):427–440. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2008.05.070287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stange K, Nutting P, Miller W, et al. Defining and measuring the patient-centered medical home. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25(6):601–612. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1291-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Regier DA, Narrow WE, Rae DS, Manderscheid RW, Locke BZ, Goodwin FK. The de facto US mental and addictive disorders service system: epidemiologic catchment area prospective 1-year prevalence rates of disorders and services. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1993;50(2):85–94. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820140007001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler R, Stafford D. Primary care is the de facto mental health system. In: Kessler R, Stafford D, editors. Collaborative medicine case studies. NY: Springer; 2008. pp. 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cunningham PJ. Beyond parity: primary care physicians’ perspectives on access to mental health care. Health Affairs. 2009;28(3):w490–w501. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.w490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.deGruy FV, Etz RS. Attending to the whole person in the patient-centered medical home: the case for incorporating mental healthcare, substance abuse care, and health behavior change. Families, Systems, & Health. 2010;28(4):298–307. doi: 10.1037/a0022049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reid RJ, Fishman PA, Yu O, et al. Patient centered medical home demonstration: a prospective, quasi-experimental, before and after evaluation. The American Journal of Managed Care. 2009;15(9):71–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strosahl K, Robinson P. The primary care behavioral health model: Applications to prevention, acute care and chronic condition management. In: Kessler R, Stafford D, editors. Collaborative medicine case studies. NY: Springer; 2008. pp. 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peek CJ. Planning care in the clinical, operational, and financial worlds. In: Kessler R, Stafford D, editors. Collaborative Medicine Case Studies. NY: Springer; 2008. pp. 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Lowe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1998;158(16):1789–1795. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kessler R. Identifying and screening for psychological and co morbid medical and psychological disorders in medical settings. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65(3):253–267. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NIH. Identifying core behavioral and psychosocial data elements for the electronic health record 2011.