ABSTRACT

Integrating behavioral health services into the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) is an important component for meeting the goals of easy access, whole person, coordinated, and integrated care. Unlike most PCMH initiatives, the Department of Defense’s (DoD) Military Health System (MHS) launched its PCMH initiative with integrated behavioral health services. This integration facilitates the MHS’s goal to meet its strategic imperatives under the “Quadruple Aim” of (1) maximizing readiness, (2) improving the health of the population, (3) enhancing the patient experience of care (including quality, access, and reliability), and (4) responsibly managing per capita cost of care. The MHS experience serves as a guide to other organizations. We discuss the historical underpinnings, funding, policy, and work force development strategies that contributed to integrated behavioral healthcare being a mandated component of the MHS’s PCMH.

KEYWORDS: Primary care, Integerated care, Collaborative care, Patient- centered medical home, Behavioral health, Mental health, Integrated-collaborative

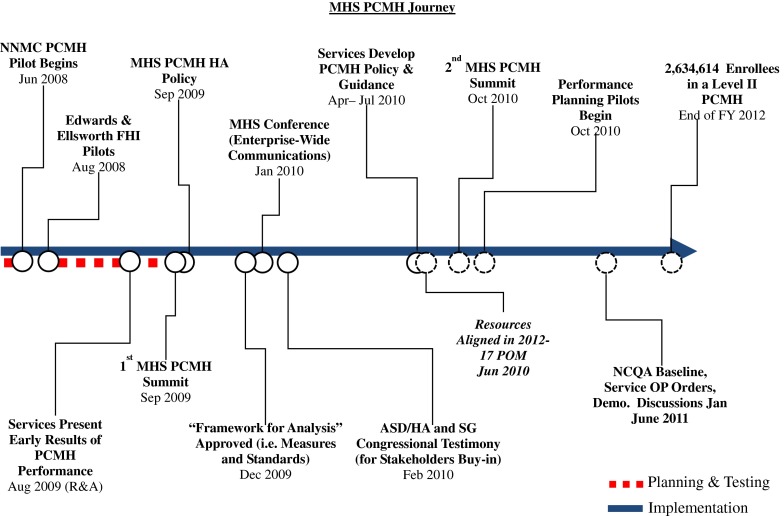

The patient-centered medical home (PCMH) joint principles establish clear domains around which to reorganize primary care to improve health outcomes. Following the publication of the joint principles, the National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA) has developed specific criteria for organizing primary care clinics around the needs of patients (based on the joint principles) and evaluating whether those needs are being met. By the end of 2010, over 1,500 clinics had been recognized by the NCQA as a PCMH [1]. The implementation and evaluation of transformed primary care systems into PCMHs across the United States is also taking place in the Department of Defense (DoD) Military Health System (MHS). The MHS is responsible for serving 9.7 million active duty and retired Service members and their families through direct care at military treatment facilities (3.3 million individuals) and local regionally managed networks. Since 2008, Tricare Management Activity, which provides oversight of regional operations and health plan administration of the MHS, has engaged subject matter experts in the planning and implementation of the PCMH throughout military treatment facilities. Figure 1 highlights the significant events in this process to date. Unlike most PCMH roll outs, the MHS effort has considered behavioral health1 services to be an important part of PCMH implementation. The MHS efforts have broad applicability to other open and closed systems of healthcare and can be used to inform the successful implementation of behavioral health PCMH services in those systems. We discuss the historical underpinnings, funding strategies, policy and work force development and the important research and measurement issues associated with the MHS integration of behavioral health in the PCMH.

Fig. 1.

MHS PCMH Journey. Note: NNMC = National Naval Medical Center; FHI = Family Health Initiative; PCMH = Patient-Centered Medical Home; R & A = Research and Assessment; MHS = Military Health System; ASD/HA = Assistant Secretary of Defense/Health Affairs; SG = Surgeons General; POM = Program Objective Memorandum; NCQA = National Committee on Quality Assurance; OP = Operations

HISTORY OF PRIMARY CARE BEHAVIORAL HEALTH INTEGRATION IN THE MHS

Integrating behavioral health services into primary care in the MHS is not a new concept. In 2000, the Air Force launched its Behavioral Health Optimization Program (BHOP). The program goals are listed in Table 1. This program embedded behavioral health providers (primarily psychologists) into primary care clinics to provide integrated-collaborative care services that could be sustained over time. The initial roll out included seven embedded behavioral health providers at military psychology internships, who were also trained to be trainers. The majority of the 24 psychology interns were subsequently trained in the Primary Care Behavioral Health model of service delivery and could provide those services after internship at their follow-on assignments at other military installations. As summarized in Table 2, the BHOP was well received by providers and patients [2]. The development of a clinical practice standards manual and a cadre of expert trainers ensured that a steady stream of 20–30 individuals a year were trained to provide BHOP services. However, because these services were not mandated, they varied from clinic to clinic with some primary care clinics having no behavioral health providers and other having providers that worked full-time.

Table 1.

Air Force BHOP goals

| Goal |

|---|

| 1. Offer services that were acceptable to Air Force primary care patients and their providers. |

| 2. Provide expanded behavioral healthcare options to, and shared decision-making with, patients. |

| 3. Increase access to behavioral healthcare within the Air Force primary care facilities and potentially minimize the number of patients being sent to network providers. |

| 4. Work collaboratively with the medical providers to foster open, collegial communication. |

| 5. Offer a broader range of behavioral health services within primary care. |

| 6. Provide a prevention focus by improving early identification and treatment of behavioral health conditions. |

Table 2.

Initial Air Force BHOP results

| Result |

|---|

| 1. 97 % of patients reported being “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with behavioral health provider care. 2. 95 % of patients reported behavioral healthcare options were at least “sufficiently” discussed. 3. 95 % of patients reported they were at least “sufficiently” involved in making decisions about their specific healthcare plan. 4. All (100 %) of the PCPs stated they would “definitely” recommend other PCPs and clinics implement BHC services. 5. 91 % of PCPs felt the BHC service helped them improve (“quite a bit” or “a lot”) their recognition and treatment of behavioral health problems. |

| 6. All (100 %) of the PCPs expressed overall satisfaction with BHC services. |

Runyan CN, Vincent VP, Meyer JG, et al. A novel approach for mental health disease management: The Air Force medical service’s interdisciplinary model. Disease Management. 2003; 6:179–188.

BHC Behavioral Health Consultant, BHOP Behavioral Health Optimization Program, PCPs Primary Care Providers

The Navy’s Behavioral Health Integration Program (BHIP) was based on favorable experiences gained through placing psychologists aboard aircraft carriers during the early 1990s. In 2003, the Navy launched a 2-year demonstration project building on the work of the Air Force BHOP. At the end of the demonstration, seven of the nine sites had implemented a BHIP service. Take home lessons from this project [3] are described in Table 3.

Table 3.

Navy BHIP take home lessons

| Take home lesson |

|---|

| 1. Achieving full impact and potential of the BHIP takes time and effort (not achievable in short-term), and may require more behavioral health provider time and attention, and Navy Bureau of Medicine management and oversight, than was devoted in the demonstration. 2. The program provided accessible behavioral healthcare to targeted patients who could benefit from it, and who may not have otherwise received it within the military treatment facility. 3. BHCs, PCPs, and patients generally perceive the BHIP as effective and were satisfied with it. 4. The BHIP was not able to achieve many intended longer-term impacts over the life of the demonstration. This may have been the result of some demonstration sites not operating sustained programs long enough for impacts to develop. It may have also resulted from lack of full program fidelity with the program logic, incomplete understanding of the program by PCPs or patients, or poor quality data for the evaluation. |

| 5. Increased operational tempo deflected attention, support, and resources away from the demonstration program and hindered its ability to be all it could have been. |

BHCs Behavioral Health Consultants, BHIP Behavioral Health Integration Program, PCPs Primary Care Providers

The Army launched the Re-Engineering Systems of Primary Care for PTSD and Depression in the Military (RESPECT-MIL) feasibility study in 2004. RESPECT-Mil was based on the three component model [4] for treating depression in primary care. This was a systems-level, care management approach to improve recognition, management, and follow-up of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) based on previous work suggesting similar approaches are effective for primary care patients with anxiety and depression [5, 6]. Key elements of RESPECT-Mil are listed in Table 4. Over the 16-month period of the feasibility study, active duty individuals were screened and identified with PTSD and/or Depression who would likely have gone undetected and untreated. The majority of those seen demonstrated clinically significant improvement [7]. To date, RESPECT-Mil has been implemented in 87 Army primary care clinics with over 1.83 million appointments [8].

Table 4.

RESPECT-Mil key components

| Key component |

|---|

| 1. Universal primary care screening for PTSD and Depression. 2. Validated, brief symptom assessments to aid diagnosis for those who screen positive. 3. Use of a nurse (RN) to assist the PCP with symptom monitoring and continuity of care for those with unmet Depression and PTSD treatment needs. |

| 4. The nurse meets regularly (typically weekly) with a behavioral health specialist to review patient status and treatment adherence and response, offering consultative management advice to the PCP. |

PTSD post traumatic stress disorder, PCP primary care provider

INDIVIDUAL SERVICE EFFORTS WERE NOT ENOUGH

Given the individual efforts from each Service, the DoD MHS had no shared vision or implementation strategy for integrating behavioral health services within primary care clinics. In June 2007, the need for such a vision and strategy was amplified when the DoD Task Force on Mental Health report [9] recommended the integration of mental health professionals into primary care settings to improve the access and outcomes of behavioral healthcare.

MENTAL HEALTH INTEGRATION WORKING GROUP

In response to the Mental Health Task Force recommendation, the Mental Health Integrated Working Group (MHIWG) was formed in February 2008. The mission of the MHIWG was to develop the clinical, administrative, and operational standards for integrated-collaborative care across the MHS. The group was led by the DoD Behavioral Health in Primary Care Program Manager (first author, CLH) who coordinated and collaborated with the Services and advocated for policy and clinical implementation change throughout the DoD.

The MHIWG included representation from the largest Services (i.e., Air Force, Navy, and Army) and across specialties (i.e., family medicine, psychology, social work, and psychiatry). The group met monthly for 22 months. Early in the process, individuals communicated with similar words, but applied very different meanings to those words. To enhance accurate communication, the group operationally defined relevant terms. They then reviewed relevant research and agreed to a set of evidence-based conclusions about integrated-collaborative behavioral healthcare. Using these conclusions and group discussion, the MHIWG established six recommendations for integrating behavioral health providers and care facilitators into primary care. These recommendations are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

MHIWG recommendations for integrating behavioral health providers and care facilitators into primary care

| 1. Number of patient enrollees determines type and number of behavioral health providers | |

| 7500+ | 1 full-time PCBH provider and 1 care facilitator |

| 1500–7499 | 1 full-time PCBH provider, or 1 full time care facilitator, or 1 full time BHP providing PCBH and care facilitator services |

| 2. PCBH provider and care facilitator positions are owned by the primary care clinic. These individuals will not be responsible for providing outpatient specialty behavioral healthcare. | |

| 3. PCBH providers and care facilitators will incorporate the following for the detection, assessment, and treatment of major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders | |

| a. Evidence-based screening b. Evidence-based treatment guidelines c. Systematic follow-up assessment and focus on continuity of care d. Patient education and use of patient self-management strategies e. Effective interface between primary care and specialty behavioral health f. Supervision for care facilitators by a behavioral health specialist g. Consultation with psychiatry on psychotropic medication | |

| 4. Standards for integrated-collaborative care programs shall include, but are not limited to | |

| a. Administrative, procedural and operational standards for PCBH providers, care facilitators, and psychiatric medication consultation and recommendations. Core competencies, skills, and standards for those who serve as expert trainers of behavioral health providers and care facilitators. b. Core competencies, skills, and standards that PCBH providers and care facilitators must meet to be credentialed for integrated-collaborative care practice. c. Minimum Service-wide standards that adapt current evidence-based DoD/VA clinical practice guidelines. d. Service and clinic assessment of fidelity of Service integrated-collaborative care standards and symptom and functional outcomes of patient care. e. Service and clinic assessment of fidelity of Service integrated-collaborative care standards and symptom and functional outcomes of patient care. | |

| 5. Service-level oversight of integrated-collaborative care programs. Oversight responsibilities shall include, but are not limited to: | |

| a. Advising senior Service staff on a range of programs and services required to fully implement and sustain integrated-collaborative care. b. Assisting with planning strategies to support implementation and administration of Service-wide programs; establishing and altering Service-level goals and measures as appropriate. c. Assisting with ongoing Service-level program evaluation plans for components and models of integrated-collaborative behavioral health services in primary care. d. Guide Service-level evaluations through resources such as reports, site visits, process reviews, studies and surveys. e. Participating in Tri-Service efforts to create and maintain Service-level data bases, reporting procedures, and data displays that permit the integration of Service databases, and create common implementing practices that permit cross-service comparisons of programs. f. Establish feedback mechanisms to ensure ongoing information is received from all relevant stakeholders. g. Making recommendations on implementation, alteration, or discontinuation of components and models of integrated-collaborative behavioral health services in primary care. h. Developing Services-level quality assessment to assess fidelity to administrative, operational and clinical component standards of integrated-collaborative care. i. Providing Service representation to an ongoing DoD ICC committee, headed by Health Affairs, which will coordinate, facilitate and assess ICC efforts at the DoD level and among each Service. | |

DoD Department of Defense, ICC Integrated-Collaborative Care, MHIWG Mental Health Integration Working Group, PCBH Primary Care Behavioral Health, VA Veterans Affairs

NOT ALL GOOD IDEAS ARE FUNDED (AT LEAST NOT RIGHT AWAY)

The MHIWG recommendations were briefed to key stakeholders (e.g., the Air Force, Army and Navy, Deputy Surgeons General and Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Clinical and Program Policy) in the MHS. The goal was to ensure that the policy makers were clear on the recommendations and to secure the approval to move forward with putting the recommendations into formal MHS policy. While there was clinical endorsement of the recommendations, DoD leadership expressed concern that moving forward without secured funding for the many additional behavioral health personnel required would put the Services at risk for having an unfunded mandate which would require funds to be pulled from other areas to meet the new policy standards.

FINANCE

An opportunity to address the need for secured behavioral health personnel funding surfaced in response to the February 2010 DoD Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR) Report. This report directed the DoD to undertake a wide-ranging review of strategies, programs, and resources including healthcare. The publication of this report coincided with the issuance of the Services budget requests. A section of this QDR report focused on lowering military health systems cost, while striking a balance with the “Quadruple Aim” of (1) maximizing readiness, (2) improving the health of the population, (3) enhancing the patient experience of care (including quality, access, and reliability), and (4) responsibly managing per capita cost of care [10].

In response to the QDR report, the MHS conducted a review of current programs, their alignment with the Quadruple Aim and the changes that were needed to realize key strategic healthcare imperatives. The PCMH was identified as a primary target to meet the goals of the Quadruple Aim. During this process, there were multiple meetings involving finance, personnel, and subject matter experts throughout the MHS to determine the component pieces of the PCMH, funding and potential return on investment. At various meetings with these personnel, finance and policy decision makers, the DoD Program Manager for Behavioral Health in Primary Care advocated for the importance of funding the behavioral health piece of the PCMH. Using the conclusions reached by the MHIWG and continuing to work with subject matter experts, he identified how behavioral health integration would impact the MHS strategic imperatives as summarized in Table 6. This information was also used to estimate the minimum staffing ratios and associated cost for behavioral health personnel between the fiscal years 2012 to 2016. As the result of many invested individuals, the funding for ongoing support of 470 full-time PCMH behavioral health personnel was initiated in January 2012.

Table 6.

Behavioral health in the PCMH: expected impact on MHS strategic imperatives

| Strategic imperatives |

|---|

| 1. Improved psychological health-screening referral and engagement. 2. Improved evidence-based care for depression and anxiety consistent with CPGs. 3. Improved engagement of patients in healthy behaviors (e.g., quit smoking). 4. Decreased per-member per-month cost. 5. Decreased patient use of emergency services. 6. Improved patient satisfaction with and access to comprehensive healthcare. 7. Improved PCMH staff satisfaction. 8. Improved efforts to identify and effectively manage those at risk for suicide. |

| 9. Recapture family member behavioral health services from purchased network care. |

CPGs Clinical Path Guidelines, MHS Military Health System, PCMH Patient-Centered Medical Home

POLICY

Once the funding was secured, the MHS could move forward with drafting policy. The goal was to take the recommendations from the MHIWG listed in Table 5 and transform them into a DoD policy document that would ensure minimum, standards, competencies, and evaluation of impact within and across the Services. A workgroup was assembled to draft this policy that included psychology, psychiatry, and primary care provider experts. After 9 months of highly detailed work, with particular attention focused on specific wording choices, the group completed a 25-page draft that serves as the foundation for proposed Departmental policy. Presently, the draft policy document is under technical and legal review in an estimated 12 month coordination process before it can be formally published (Table 7).

Table 7.

Behavioral health personnel in the PCMH DoD policy instruction content areas

| Policy instruction content areas |

|---|

| 1. Minimum staffing levels. |

| 2. Training standards for behavioral health providers and care facilitators. |

| 3. Full-time Service-level primary care behavioral health program managers. |

| 4. Comprehensive Service practice standards that detail the clinical and administrative standards for behavioral health providers and care facilitators. |

| 5. Comprehensive expert trainer standards. |

| 6. An MHS oversight committee charged with ongoing development dissemination and evaluation of standards implementation and outcome. |

MHS Military Health System

WORK FORCE DEVELOPMENT

Working in an integrated-collaborative care environment requires specialized skills [11, 12]. The vast majority of behavioral health providers and care facilitators that will be hired will not have the requisite skills to work efficiently and effectively in the PCMH. Behavioral health providers in particular, are often trained for assessment and intervention in specialty mental health clinics that use 1 to 2 hour appointments and extensive mental health reports. The clinical, administrative, and operational standards and cultural norms that work well in outpatient specialty mental health, are a poor match for the culture, fast pace, and population health focus of behavioral health service delivery in the PCMH [13]. As such, the DoD draft policy instruction sets minimum training criteria and core competencies for behavioral health providers and care facilitators consistent with Air Force, Navy and Army publications [14–16]. Currently, none of the Services have the full complement of trainers needed and are working to combine the existing behavioral health provider and care facilitator training assets to ensure that the first wave of hires, gets appropriate and timely training consistent with the draft DoD policy instruction. Each Service is developing their own set of expert trainers to ensure efficient and effective training personnel are in place. As a general rule, training will involve didactic and experiential training prior to behavioral health providers and care facilitators seeing patients as well as in clinic observation and training to ensure minimum core competencies can be demonstrated in a real world setting.

EVALUATION/MEASUREMENT

Inclusion of behavioral health providers and care facilitators in the PCMH, were not initially considered as independent variables upon which to evaluate the impact of PCMH outcomes. At the same time, the phased implementation of the PCMH in the MHS, with the staged integration of behavioral health provider and care facilitators into those teams, provides a unique opportunity to evaluate the potential differential impact of outcomes for PCMHs with and without behavioral health providers and care facilitators. There are a number of variables that could be evaluated including patient, provider, clinic and system level, process and outcome metrics. The MHS is reviewing potential outcome and process measures that align with the Quadruple Aim and MHS strategic imperatives. Variables under consideration are listed in Table 8.

Table 8.

Measuring impact of behavioral health personnel integration into the PCMH

| Strategic imperative | Potential performance measures | Association With 2011 PCMH NCQA Standards | National recommendation standards/screening and/or inclusion of BH intervention | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Readiness | Enhance psychological health and resiliency active duty and family members | Anxiety | PCMH 1 Element E Factor 1 and 4 | VA/DoD CPG 2010: Management of PTSD |

| 1. % Enrollees screened for an anxiety disorder (e.g., GAD-7) | PCMH 2 Element C Factor 7 | |||

| 2. % Screening positive for an anxiety disorder | PCMH 3 Element A Factor 3 | |||

| 3. % Diagnosed with an anxiety disorder | PCMH 4 Element B Factor 3 | |||

| 4. % Positive managed in PCMH only | PCMH 5 Element B | |||

| 5. % With symptoms and functioning improvement pre/post (use of a general measure [e.g., Duke Health Profile, Behavioral Health Measure-20] and/or specific anxiety measure) | PCMH 6 Element B Factor 1 | |||

| 6. % Attending initial behavioral health in PCMH appointment by beneficiary category | ||||

| 7. % Referred to specialty outpatient behavioral health | ||||

| 8. % Attending initial specialty outpatient behavioral health appointment | ||||

| Depression | PCMH 1 Element E Factor 1 and 4 | USPSTF-2009 Grade B Recommendation | ||

| 1. % Enrollees screened for major depressive disorder & suicidality (Patient Health Questionnaire-2 & suicide question # 9 from Patient Health Questionnaire-9) | PCMH 2 Element C Factor 7 and 9 | VA/DoD CPG 2009: Management of Major | ||

| 2. % Screening positive for a Major Depressive Disorder | PCMH 3 Element A Factor 3 | Depressive Disorder | ||

| 3. % Diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder | PCMH 3 Element B Factor 1 | |||

| 4. % Positive managed in PCMH only | PCMH 4 Element B Factor 3 | |||

| 5. % With symptoms and functioning improvement pre/post (general measure [e.g., Duke Health Profile, Behavioral Health Measure-20] and/or specific depression measure e.g., Patient Health Questionnaire-9) | PCMH 5 Element B | |||

| 6. % Attending initial behavioral health in PCMH appointment by beneficiary category | PCMH 6 Element A Factor 1 & 2 | |||

| 7. % Referred to specialty outpatient behavioral health | PCMH 6 Element B Factor 1 | |||

| 8. % Attending initial specialty outpatient behavioral health appointment | ||||

| Population Health | Engage Patients in Healthy Behaviors & Delivering Evidence-Based Care | Obesity (overlaps with readiness) | PCMH 2 Element C Factor 6 | USPSTF-2011 Draft Grade B Recommendation |

| 1. % Enrollees with BMI > 30 | PCMH 3 Element A Factor 3 | VA/DoD CPG 2006: for Screening & Management of Overweight and Obesity | ||

| 2. % Enrollees screened for obesity (BMI > 30) | PCMH 4 Element B Factor 1 | |||

| 3. % Screening positive for obesity | PCMH 6 Element A Factor 1 | |||

| 4. % Working with PCMH behavioral health for intensive behavioral weight counseling and BMI change from 12 months post treatment initiation | ||||

| 5. Average BMI change for all enrollees with a BMI over 30 | ||||

| Tobacco Use (overlaps with readiness) | PCMH 1 Element E Factor 4 | USPSTF-2009 Grade A Recommendation | ||

| 1. % Enrollees who smoke | PCMH 2 Element C Factor 6 | VA/DoD CPG 2008 Treating Tobacco Use & Dependence | ||

| 2. % Enrollees screened for tobacco use | PCMH 3 Element A Factor 3 | |||

| 3. % Screening positive for tobacco use | PCMH 4 Element B Factor 1 | |||

| 4. % Diagnosed with tobacco dependence (TD) | PCMH 6 Element A Factor 1 | |||

| 5. % Diagnosed with TD Working with PCP & behavioral health in PCMH based cessation program | ||||

| 6. % Treated remaining tobacco free 12 months post quit date | ||||

| 7. % Diagnosed with TD getting cessation services out of PCMH | ||||

| Alcohol Use (overlaps with readiness) | PCMH 1 Element E Factor 4 | USPSTF-2004 Grade B Recommendation | ||

| 1. % Enrollees screened for alcohol use | PCMH 2 Element C Factor 6 | VA/DoD CPG 2009: Management of Substance Use Disorders | ||

| 2. % Screening positive for alcohol problems (Audit-C) | PCMH 3 Element A Factor 3 | |||

| 3. % Diagnosed with alcohol abuse or engaged in risky drinking | PCMH 4 Element B Factor 3 | |||

| 4. % Working with PCP & behavioral health in PCMH based treatment | PCMH 6 Element A Factor 1 & 2 | |||

| 5. % Referred to specialty outpatient alcohol treatment | ||||

| Chronic Pain (overlaps with readiness) | PCMH 1 Element E Factor 4 | IOM Report June 2011: Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, & Research | ||

| 1. % Enrollees with chronic pain condition | PCMH 6 Element A Factor 2 | Office of the Army Surgeon General: Pain Management Task Force Final Report May 2010 | ||

| 2. % Enrollees referred to PCMH behavioral health for screening/assessment as part of standard of care for all chronic pain patients | VA/DoD CPG 2007: Assessment & Management of Low Back Pain | |||

| 3. % With significant anxiety/depression or functional impairments that might benefit from cognitive/behavioral pain management skills training | ||||

| 4. % Working with PCP & behavioral health in PCMH based pain management program | ||||

| 5. % After treatment with clinically and statistically significant changes in depression/anxiety symptoms, functioning and quality of life | ||||

| 6. % with appropriate medication use | ||||

| 7. % that receive an invasive procedure | ||||

| Diabetes | PCMH 1 Element E Factor 4 | ADA 2011: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes | ||

| 1. % Enrollees with HbA1C < 7 | PCMH 1 Element G Factor 6 | |||

| 2. % Enrollees with HbA1C > 7 referred to PCMH behavioral health for screening/assessment to improve diabetes management | PCMH 2 Element C Factor 6 | |||

| 3. % that work with PCMH behavioral health for weight loss, increased physical activity, improved monitoring & management of mood | PCMH 2 Element D Factor 2 | |||

| 4. % After treatment with significant decrease in HbA1C, blood pressure, lipids, weight loss | PCMH 3 Element A Factor 1 | |||

| PCMH 6 Element A Factor 2 | ||||

| Experience of Care | Optimize Access to Care | 1. Same day access to PCMH behavioral health appointment | PCMH 1 Element A Factor 1 | |

| 2. Time to same day available new and 3rd return open appointment for PCMH behavioral health | PCMH 1 Element A Factor 1 | |||

| 3. % Who desire same day PCMH behavioral health who receive it | ||||

| 4. Satisfaction with getting timely behavioral healthcare | ||||

| 5. % of family members seen by PCMH behavioral health (potentially recaptured network care) | ||||

| Per Capita Cost | Manage Healthcare Costs | 1. Annual percent increase in per capita costs | ||

| 2. Emergency room visits per 100 enrollees per year for anything | ||||

| 3. Emergency room visits per 100 enrollees per year for behavioral health presentation | ||||

| Per Capita Cost | Enable Better Decisions | % Use of stand electronic medical record note templates for PCMH behavioral health (module/s need to be developed) | ||

| Learning & Growth | Develop Our People | Primary care staff satisfaction in general & with behavioral health services |

PCP Primary Care Provider, PCMH Patient Centered Medical Home, BMI Body Mass Index, HbA1C Hemoglobin A1c, USPSTF United States Preventive Services Task Force, VA/DoD Veterans Administration and Department of Defense, IOM Institute of Medicine, CPG Clinical Practice Guideline, ADA American Diabetes Association

The research questions, methods, data collection, and statistical analysis are vital to consider in concert with the types of measures collected. A recent Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) publication [17] details a number of key points the MHS will take into account as they develop their evaluation plan. These recommendations are intended to produce high-quality, reliable evidence on the effectiveness of PCMHs. Those key elements are listed in Table 9.

Table 9.

AHRQ recommendations for high quality evaluations of medical homes

| AHRQ recommendations |

|---|

| 1. Focus evaluations on quality, cost, and experience. 2. Include comparison practices. 3. Recognition that the PCMH is a practice-level intervention and account for clustering. 4. Include as many intervention practices as possible. 5. Be strategic in identifying the right samples of patients to answer each evaluation question. |

| 6. Rethink the number of patients from who data are collected to answer key evaluation questions. |

PCMH Patient-centered medical home

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Despite the work done to date, the MHS has a long way to go to realize the intended outcomes of integrated-collaborative behavioral health services in the PCMH. A great deal of work is left to be done in hiring and training personnel, establishing evaluation questions and methodology, developing standardized data collection mechanisms and adapting to the unexpected consequences of this endeavor. There are several recommendations based on our experience that we believe should be actively considered when developing and launching integrated behavioral health services in a medical home.

Include the appropriate healthcare professions (e.g., behavioral health and primary care) when developing a service delivery model and standards. Although this may take longer than desired on the front end of development, the unique healthcare views can strengthen the overall program and improve stakeholder buy-in.

Ensure that all collaborators are using terminology consistently. When possible establish an agreed upon set of definitions and constructs.

Include finance, personnel, and management individuals during the process of program development. Regardless of how fantastic your plan is, there must be a way to fund it, staff it, and have management in full support for there to be a chance of success.

Identify a behavioral health and/or primary care champion who will lead the healthcare professionals in program development and can also speak the language of finance, personnel, and management. Having a strong healthcare advocate that can inform these individuals with real world stories, scientific data and potential return on investment will facilitate movement of the clinical and operational worlds in the same direction.

Ensure that the rationale for establishing integrated-collaborative behavioral health is clear, evidence-based or evidence-informed, and considers the operational and financial barriers within a given system.

Carefully determine when to present proposals to senior leadership. Only do so when there is a clear rationale and difficult questions can be addressed in thoughtful ways.

Develop an agreed upon set of clinical and administrative standards that are observable, can be enforced, and a method to train or ensure the work force is trained to those standards. There must be fidelity to a service delivery model if the expected outcomes are to be achieved.

Carefully consider what impact is expected from integration and develop a set of metrics and effective evaluation design that will allow scientifically robust conclusions to be drawn. Being able to provide return on investment results to patients, providers and management, will facilitate ongoing support of successful efforts and allow a change of course in service delivery if desired outcomes are not being reached.

Overall, the process of establishing integrated-collaborative care as an important and valued component of the PCMH to the point where it was financed and mandated throughout the MHS took over 11 years. These decisions were largely based on positive experiences with integrated-collaborative care, a growing evidence base, and sustained marshalling of political support. Now, the hard part begins; hiring, training, and maintaining the fidelity of the care that is intended to be provided. Additionally, there are numerous opportunities for testing the impact of integrated-collaborative care on clinical, operational, and financial outcomes. Integrated-collaborative care will sustain itself in the MHS only if it demonstrates that it enhances readiness, improves the health of the population, enhances the patient experience of care, and responsibly manages the per capita cost of care.

Footnotes

Behavioral health is being used as a generic term to include to include services for health behavior change like weight loss, substance dependence/abuse/misuse, behavioral medicine interventions, like chronic pain management, and general mental health services, like panic disorder.

Implications

Research: Researchers need to be aware of the methodological and statistical processes needed for patient-centered medical home research in order to derive scientifically robust data, prior to initiating a study.

Practice: In order to have the best chance to reach desired healthcare outcomes and population health impact, healthcare systems and practitioners need to know and be able to engage in, specific benchmarked behavioral health core competencies for patient-centered medical home behavioral health services.

Policy: Policy makers need to be aware of the importance of upfront funding and setting minimum standards for behavioral health clinical services to optimize the chances of reaching the health and financial return on investment sought.

The opinions and statements in this article are the responsibility of the authors, and such opinions and statements do not necessarily represent the policies of the Department of Defense, the United States Department of Health and Human Services, or their agencies.

References

- 1.NCQA’s Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) 2011. Retrieved from the PCMH 2011 Overview link on February 29, 2012 from http://www.ncqa.org/tabid/1472/Default.aspx.

- 2.Runyan CN, Vincent VP, Meyer JG, et al. A novel approach for mental health disease management: The Air Force medical service’s interdisciplinary model. Dis Manag. 2003;6:179–188. doi: 10.1089/109350703322425527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris DM, LeFavour J. Final evaluation of Navy’s medicine’s behavioral health integration program (BHIP) two-year demonstration project. The CNA Corporation; 2005.

- 4.Oxman TE, Dietrich AJ, Williams JW, Jr, Kroenke K. A three-component model for reengineering systems for the treatment of depression in primary care. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(6):441–450. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.43.6.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dietrich AJ, Oxman TE, Williams JW, Jr, et al. Re-engineering systems for the treatment of depression in primary care: cluster randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2004;7466(329):602. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38219.481250.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zatzick D, Roy-Byrne P, Russo J, Rivara F, et al. A randomized effectiveness trial of stepped collaborative care for acutely injured trauma survivors. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61(5):498–506. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.5.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engel CC, Oxman T, Yamamoto C, et al. RESPECT-Mil: feasibility of a systems-level collaborative care approach to depression and post-traumatic stress disorder in military primary care. Mil Med. 2008;173:935–940. doi: 10.7205/milmed.173.10.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engel CC, Weil J, Curry J et al. Disseminating effective integrated mental health and primary care services for PTSD and depression in the U.S. military. Paper presentation for the American Psychiatric Association presidential symposium 3: New approaches to integration of mental health and medical health services; Katon WJ, Unützer J, Zatzick D, Druss B, Engel CC. 165th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association. Philadelphia, PA, May 7, 2012.

- 9.An achievable vision: Report of the Department of Defense Task Force on Mental Health. Falls Church: Defense Health Board; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Defense. Quadrennial defense review report; 2010.

- 11.Hunter CL, Goodie JL, Oordt MS, et al. Integrated behavioral health in primary care; step-by-step guidance for assessment and intervention. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson PJ, Reiter JT. Behavioral consultation and primary care: a guide to integrating services. New York: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hunter CL, Goodie JL. Operational and clinical components for integrated-collaborative behavioral healthcare in the patient-centered medical home. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28:308–321. doi: 10.1037/a0021761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Primary behavioral health care services practice manual: version 2.0. San Antonio, TX: United States Air Force; 2011.

- 15.Navy medicine primary behavioral health care services behavioral health integration program: practice manual for the demonstration project: version 3.0. Washington, DC: United States Navy; 2003.

- 16.RESPECT-MIL care facilitator reference manual: three component model for primary care management of depression and PTSD (Military version). Uniformed Services University; 2008.

- 17.Meyers D, Peikes D, Dale S, et al. Improving evaluation of the Medical Home. AHRQ Publication No. 11-0091. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. [Google Scholar]