Abstract

In the United States, most adults state that religion plays an important role in their lives and claim a religious affiliation. For gay, bisexual, and transgender persons (GBT), the story is unique because their sexual and gender identity is not accepted by most religions. The purpose of this article is to analyze the role of religiosity in the life course of Latino GBTs raised as Catholics. Data come from 66 life history interviews with Latino GBTs living in Chicago and San Francisco, who grew up as Catholics. We found a religious trajectory that mirrored participants’ developmental stages. During childhood, religion was inculcated by the family, culture, and schools. In adolescence, many experienced a conflict between their religion and their GBT identity, and in adulthood, they reached a resolution. Most participants abandoned Catholicism to join other religions or spiritual groups that they perceived to be welcoming. We found participants engaging in a remedial ideological work to reconcile their religious values and their identity.

Keywords: Latinos, gay men, homosexuality, religiosity, spirituality, Catholicism, life course, HIV/AIDS

INTRODUCTION

Religion frames childhood experience from which individuals form their adult religious or spiritual identities (Schuck & Liddle, 2001). In the United States, most adults (59%) claim a religious affiliation, believe in God (95%), pray (90%), and read the Bible (69%). In addition, 89% of the adult population states that religion plays an important role in their lives (Dillon, 2003). This story, however, is different for gay, bisexual, and transgender persons (GBT). Their sexual and gender identity is not accepted by most religions, and they tend to abandon their religion of origin at higher rates than their heterosexual peers (Schuck & Liddle, 2001; Sherkat, 2002). Yet, gay men appear to be as active in religious matters as heterosexual females, who report to be are the most religious of all groups in the United States (Sherkat 2002).

The purpose of this article is to use life histories to analyze the role of religiosity in the life of Latino GBTs who grew up as Catholics and who are activists for HIV/AIDS and gay related issues. We also explore why some individuals remained Catholics in adulthood, while others abandoned their childhood religion. Individuals raised as Catholics were selected because it is the predominant religion in Latin America and among Latinos in the United States (Hunt, 1998). Of the one billion Catholics worldwide, 63% live in the Americas (Catholic News, 2004; Religion News Service, 2001). In 2001, there were about 60 million Catholics in the U.S., 24% of the American population (American Religion Data Archive [ARDA], 2000).

The study of religion is essential because from early childhood, religion provides values and principles to guide actions, to develop a sense of purpose and self-identity, and is also a source of strength (Fellows, 1996; Flannely & Inouye, 2001). It offers guidance on topics such as becoming a moral and responsible adult and community member, sex and procreation, and death. Religion also serves cultural and communal functions through church attendance, holidays, feasts, and obligations (Flannely & Inouye 2001). Furthermore, religiosity is closely related to volunteerism and activism. Membership in religious organizations, and particularly attendance to religious services, is a predictor of civic participation in the United States (Hodgkinson, 1995; Smith, 1994; Wilson & Musick, 1997). Highly religious individuals are more likely to provide help through formal volunteering than less religious individuals (Wilson & Musick, 1997). The relationship between activism and religiosity may also be reverse, activism may lead individuals to seek a more religious or spiritual life. Yet, little is known about religiosity in the lives of Latino GBTs. Thus, in this article, we utilize a life course perspective to analyze the role of religiosity, identify its trajectories, transitional points, and changes in the lives of a rarely studied group of GBTs.

The concepts of religion and spirituality are distinct yet intertwined. Religion refers to an “organized system of beliefs, practices, rituals, and symbols” that relate to a higher power (Koenig, McCullough, & Larson, 2001), occurring within an institution or outside the confines of an institution, usually referred to as “popular religion” (Levine, 1986). The concept of spirituality is less institutionally focused and is based on a personal quest for meaning, understanding, purpose, and relationship to the sacred or transcendent. It may be embedded within religious rituals or humanistic approaches (Koenig, McCullough, & Larson, 2001; Myers, Sweeney, & Witmer, 2000). While many individuals maintain a religious affiliation, others consider themselves spiritual, but not necessarily religious. Both religiosity and spirituality can serve as a coping mechanism in times of difficulty, as they supply diverse forms of social support (Flannely & Inouye, 2001).

LIFE COURSE TRAJECTORIES AND RELIGIOSITY

The concept of life course is comprised of two notions that help trace the role of religion in people’s lives: trajectory and transition (Clipp, Pavalko, & Elder, 1992; Elder 1985; Ingersoll-Dayton, Krause, & Morgan, 2002; Peacock & Paloma 1999). Trajectory refers to the overall pathway that occurs over individuals’ lifetime. Trajectories are mapped by linking transitions across the life course. Transitions of significant magnitude constitute turning points that redirect trajectories (Clipp et al., 1992), and are affected by context, social trends and historical events (Cohler, Hostetler, & Boxer, 1998). Transitions may be attributed to factors such as the maturation process and adversity that are experienced throughout life (Wink & Dillon, 2002). Responses to transitions vary, as some individuals respond to those events through despair and faith crises (Idler, Kasl, & Hays, 2001), while others turn to their religion for support (Bevins & Cole, 2000; Kimble & McFadden, 1995; Pargament, 1997). A life course trajectory anticipates certain events in a sequential order (e.g., school, graduation, first job, parenthood, retirement, death), but some of these events may not occur for the majority of GBT individuals.

The study of life trajectories provides an understanding of how individuals selectively share discourses and interpret their lives (Cohler et al., 1998). Narratives of life stories are social constructions, and through the narratives, individuals create meaning for their lives by interpreting events (Denzin, 1989; Hyden, 1997; Hinchman & Hinchman, 1997). Narratives are not necessarily accurate accounts of events, but rather they give individuals the space to select and link events from their perspective, as well as to provide significant personal meaning (Novitz, 1997). As social constructions, life histories are shaped by cultural and societal norms, which individuals follow in deciding how to live and interpret their lives (Meyer, 1988).

Religiosity and religious practices are cultural norms, which often follow a life course trajectory with related transitions. The following religious dimensions contribute to an overall religious trajectory and can be transitioned by various life events (Ingersoll-Daytonet al., 2002). First, religious affiliation or denomination may be maintained or changed across the life course. Second, religious participation, which refers to church attendance and involvement in church activities, varies depending on individuals’ needs. Third, religious practices and beliefs, caring for the needs of others, and the nature and content of prayer, can also change. Finally, religious commitment, which refers to prioritizing religion across the life course, understanding and learning about faith, deepening one’s relationship with and trust for God, and changes in religious certainty or doubt, can be transformed throughout life (Ingersoll-Dayton et al., 2002). These four dimensions can contribute to define religious trajectories as either stable, increasing, or decreasing over the life course, depending on the specific life events. For example, religious participation may increase with life events such as marriage, child rearing, and negative life events, and decrease with the end of child rearing, illness, or other hardships, and dissatisfaction with religion (Ingersoll-Dayton et al., 2002; Peacock & Paloma 1999).

RELIGION AND HOMOSEXUALITY

GBTs, generally speaking, may have a different life trajectory compared to the majority of their heterosexual peers (Savin-Williams, 2001). Similar to heterosexual youth persons, most GBT experience common factors of sexual development, such as growth spurts, attachment, intimacy, autonomy, individualism, and identity. GBT individuals, however, encounter unique experiences, such as growing up among family members, friends, and societal institutions (e.g., schools and religious organizations) that prescribe a heterosexual lifestyle, and challenge them to negotiate between their sexual identity or conforming to dominant norms (Savin-Williams, 2001). Such experiences of GBT individuals are outside the norms of which life course theory has been grounded (Cohler et al., 1998). A typical life course trajectory includes marriage and parenthood. Even though many gay couples have children or live in partnership, most do not follow such traditional normative path.

One of the central societal institutions that affect individuals’ trajectories and values is religion. Religious institutions and dogma significantly influence the societal and personal belief systems regarding homosexuality (Gramick, 1983). The teachings of many denominations within Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, for instance, maintain traditions of intolerance to GBTs (Barrett & Barzan, 1996; Davidson, 2000; Fukuyama & Ferguson,2000; Gramick, 1983; Sherkat, 2002). Followers of these teachings condemn and devalue GBTs, whose sexual behaviors are considered sinful (Davidson, 2000; Ritter & O’Neill 1989; Sherkat, 2002; Schuck & Liddle, 2001). Within Roman Catholicism, homosexual orientation has been charged as a tendency toward a moral evil (Ratzinger, 1994).

Despite the contention between religious teachings and homosexuality, the available literature offers a limited view, especially with respect to Latinos. Shuck and Liddle (2001), for instance, found that in the coming out process, the main conflict experienced by GBTs stems from one’s religious teachings. However, only 5% of the sample was Latino. In another instance, Rodriguez and Ouelette (2000) conclude, based on a sample of four Latino gay men members of the Metropolitan Community Church, that these men have successfully integrated their religious and sexual identities, after feeling rejected and leaving their religion of origin. Others (e.g., Galvan, 1999) have found that some gay men maintain a personal understanding of God or have abandoned organized religions as a reaction to their churches’ intolerance toward homosexuality.

As children, and similarly to heterosexual individuals, GBTs learn about religion and God from their parents (Sherkat, 2003), particularly from their mothers or other female relatives (Rodriguez & Ouelette, 2000). The first, and perhaps major, life transition in the lives of GBTs occurs when their homosexual desire becomes salient and they adopt a homosexual identity. This usually takes place during adolescence and early adulthood (Ramirez-Valles & Diaz, 2005). Some authors have found that homoerotic desires usually start as early as 8 or 9 years of age (Herdt 7 Boxer, 1993; Savin-Williams, 1998). At that point, many gay youth feel that they do not fit in and opt to keep their feelings secret. Family, religion, and social environment all contribute to push GBT youth to conform to heterosexual roles and norms. Many of them experience the conflict between their sexuality and religious beliefs, with feelings of rejection, shame, and guilt (Barret & Barzan 1996; Newman & Muzzonigro 1993; Ritter & O’Neill 1989). Their identity as moral beings comes into crisis, often leading them to decrease or cease their religious involvement. How and when they resolve that conflict shapes their future religious involvement. According to some authors (Herdt & Boxer, 1993; Savin-Williams, 1998), GBT youth must undergo radical changes to manage such conflicts. First, they must unlearn that heterosexuality (e.g., marriage to the opposite gender) is not the only and natural way of being. Second, they must unlearn the stereotypes associated with homosexuality. Third and last, these youth must learn how to be gay, which requires a reconstruction of social relations and disclosure of this identity to others. This last step is the end product of coming out, but can be a lifelong process and may not reach closure (Herdt & Boxer, 1993).

After coming out and adopting a GBT identity, these individuals may follow at least four plausible religious trajectories (Ritter & O’Neill 1989). In the first trajectory, individuals remain Catholics, either by reconciling their sexual identity with their religion, or by concealing their sexuality from their religion (Barret & Barzan, 1996; Fellows, 1996). Remaining within the religion of origin could require what Berger (1981) calls “remedial ideological work,” to address the discrepancies between their sexual identity and their religious beliefs. Berger argues that individuals accommodate and redefine their beliefs to their actions to create harmony between the two. The second trajectory involves renouncing Catholicism in favor of congregations or groups within traditional religious (e.g., Metropolitan Community Church, Episcopalian), perceived as more welcoming of GBTs. In the third possible trajectory, GBT persons renounce their religion and join non-Judeo Christian religions, such as Buddhism (Barrett & Barzan 1996; Schuck & Liddle, 2001). Finally, in a fourth trajectory, GBTs may abandon all religious groups and teachings, in which some individuals may consider themselves spiritual but not religious, while others may opt not to maintain any ties with the spiritual or religious world.

The role and the trajectory of religiosity among nonethnic minority GBTs unfortunately remain unexplored, in both gay and religious studies. For most Latinos in the Americas, Catholicism, either institutionalized or popular, is intrinsically connected with family, gender, culture practices, and everyday life. Latino GBTs must disentangle the communion of these factors as they develop a sexual and gender identity. The purpose of this article, thus, is to analyze the religious and spiritual life of Latino GBTs. Following a life course approach and using life history data, we explore several questions: What role does religion play in their lives? How does religiosity change over time, from childhood to adulthood? How do these GBTs negotiate sexual and gender identities with their religious and spiritual life?

METHODS

Semistructured life history interviews were conducted in 2001 and 2002 with a sample of 80 Latino GBTs living in Chicago (n = 40) and San Francisco (n = 40). The purpose of the larger study was to investigate the protective effects of community involvement on sexual risk behavior. As a part of the interview, participants were asked about their religious affiliation, religious practices, and the overall impact of religiosity and spirituality across the life course. Interviews were conducted in the language preferred by participants, either English, Spanish, or both. The interviews were tape recorded and professionally transcribed in their original language. Analysis was conducted in the original language and excerpts were translated to English, when needed, for this manuscript.

To participate in the study, participants had to be 18 years old or older; self-identify as Latino and gay, bisexual, or transgender, and have been involved in HIV/AIDS- or GBT-related community work as volunteers or activists. Participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 63 years old with a mean age of 36 (see Table 1 for demographic information). Most were born in the United States (40%) or Mexico (39%). Of those born in the U.S., the majority were of Mexican (72%) or Puerto Rican (16%) descent. Most participants had some college or vocational education (35%) or a college degree (30%). Seventy-two individuals (90%) identified as homosexual or gay men, 3 (4%) as bisexual men, and 5 as transgender (6%). Less than half of the sample was HIV positive (41%).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of interviewed participants by site

| Characteristics | Chicago n (%) Total N = 40 |

San Francisco n (%) Total N = 40 |

Total N (%) (Total N = 80) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| <29 | 8 (20) | 9 (23) | 17 (21) |

| 30–39 | 23 (57) | 16 (40) | 39 (49) |

| 40–49 | 6 (15) | 11 (27) | 17 (21) |

| 50> | 3 (8) | 4 (10) | 7 (9) |

| Birthplace | |||

| USA | 15 (38) | 17 (42) | 32 (40) |

| Mexico | 15 (38) | 16 (40) | 31 (39) |

| Puerto Rico | 5 (13) | 1 (3) | 6 (7) |

| Other | 5 (13) | 6 (15) | 11 (14) |

| Ethnicity if born in the U.S. (n = 32) | |||

| Mexican | 9 (60) | 14 (82) | 23 (72) |

| Puerto Rican | 3 (20) | 2 (12) | 5 (16) |

| Other | 3 (20) | 1 (6) | 4 (12) |

| Sexual orientation | |||

| Homosexual/gay | 37 (92) | 40 (100) | 77 (96) |

| Bisexual | 3 (8) | 0 | 3 (4) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 39 | 36 | 75 |

| Transgender | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 5 (13) | 4 (10) | 9 (11) |

| High school diploma | 2 (5) | 4 (10) | 6 (8) |

| Vocational/Some college | 11 (28) | 17 (43) | 28 (35) |

| College graduate | 16 (40) | 8 (20) | 24 (30) |

| Graduate school | 6 (15) | 7 (18) | 13 (16) |

| Employment | |||

| Full-time | 27 (68) | 17 (43) | 44 (55) |

| Part-time | 7 (18) | 3 (8) | 10 (13) |

| Unemployed | 6 (15) | 9 (23) | 15 (19) |

| Public aid | 0 | 8 (20) | 8 (10) |

| Student | 0 | 3 (8) | 3 (4) |

| HIV status | |||

| Positive | 15 (37) | 18 (45) | 33 (41) |

| Negative | 23 (57) | 22 (55) | 45 (56) |

The interview data were analyzed using a combination of categorical content analysis and interpretative approach (Lieblich, Tuval, & Zilber, 1998). N5 software (formerly known as NUDIST) (QSR International, Victoria, Australia) was used for data management. All participants’ responses related to religiosity were extracted for further analysis. Themes analyzed included the mode of religious and spiritual transmission, the cultural aspects of religiosity or spirituality, conflicts between religion and sexuality, and the respondents’ levels of participation and commitment to religion in childhood and adulthood. All study participants’ levels of religiosity were coded in both childhood and adulthood as low, moderate, and high, which is described in greater depth in the results section. The names of participants were changed for this article to protect their identities.

RESULTS

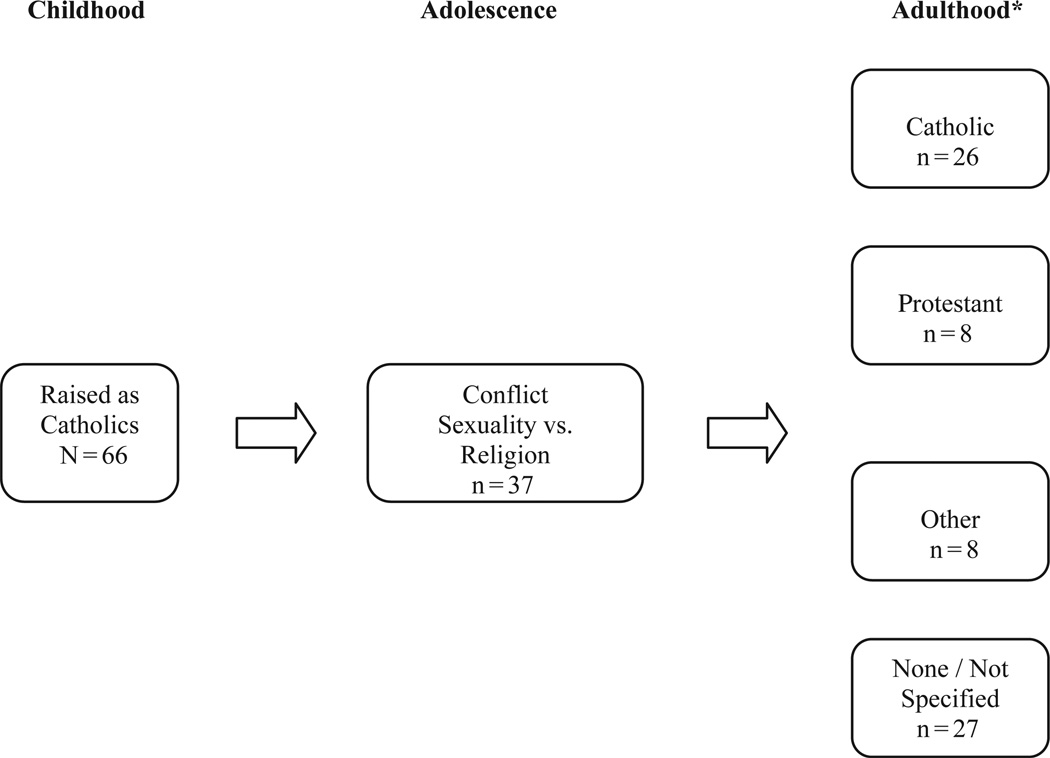

Our overall goal is to describe the religious and spiritual life trajectories of Latino GBTs who grew up as Catholics. Of the 80 life history interviews, 66 (83%) participants indicated being Catholic during childhood. Figure 1 illustrates the trajectory of these 66 participants along three time periods: childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. The presentation of the results follows Figure 1. In the first section, we discuss how religion was instilled in participants, from what sources, and the extent of their level of religiosity. Then, in adolescence, we find that over half of the participants (n = 37) experienced a conflict because of their religious values and their sexual orientation. Most of them eventually abandoned the Catholic Church and joined other religions or spiritual practices by the time they reached adulthood. In the adulthood stage, we present their choices of religious and spiritual practices.

FIGURE 1.

Religious Life Trajectory of Catholic-raised Latino Gay Men and Transgender Person

Childhood

We refer to childhood as a developmental stage that encompasses the formative years until the pre-teen years. Catholic religious education was, in most cases, provided by a family member, mainly a female figure, such as mother or grandmother. Other sources include Catholic schooling and general cultural practices. As expected, the level of participation and commitment varied among the participants.

Religious Education

The mode of transmission of religious values and practices was similar among all participants. It was primarily imparted by the mother or grandmother, and secondly through other family members, formal religious education, and local cultural practices.

Mother and grandmother

Most participants recalled their mothers playing a fundamental role in their religious education. Jimmy, for instance, notes: “My mother always instilled religion in me. She is very Catholic. There is no mass or rosary that she misses.” Similarly, Vladimir, who grew up in a small town in Mexico, recalls his mother taking all his siblings to church, especially on Sundays, where attending services had a sense of obligation: “I’d go to church. Sometimes I joined my mom, who was always praying and asking God for us not to lose our way. She’d say, ‘you must go to church on Sundays.’” Children had little or no choice; religion was imposed on them, as Lorenzo explains: “I’d go to church with my mom. I went with her for many years. She’d take me even if I didn’t want to go.”

Grandmothers are the second most cited source of religious teaching, and they are portrayed in a manner similar to mothers. Born and raised in Puerto Rico, Josué recounts how his grandmother would make him pray the rosary: “When my grandma was in the house, it was a torment, because with her it was about kneeling down at 7 P.M. to pray the rosary.” The influence of grandmothers takes place regardless of the parents’ presence in the children’s life. Renato was an altar boy and member of the church choir. He recalls, “[my grandmother] would go to church every Sunday, and she really wanted me to go with her. … I got really into Catholicism at that young age even though my parents were not.”

Other relatives

Other relatives, such as fathers and grandfathers, are also mentioned by participants as sources of religious education, but they play minor roles. Gustavo is one of the very few Latino gay men who learned about prayer and Catholic values from his father. “My dad, despite being very hard, used to pray every day. He had a calendar with the prayers, and he’d pray all of them. Even to punish us, he’d ask us to kneel down and pray … if you didn’t do it, he’d lash your hand.”

Religious schools

Eight participants (12%) noted that Catholic schools were their source of religious teachings. Generally speaking, Catholic schools in Latin American are private and expensive, thus, an indicator of a high or middle social class status. For Tomas, who went to a public Catholic school in Colombia, where Catholic theology is included in the curriculum of most public schools, “Catholic religion was an obligation. You’d get to school to pray before class. You’d get the blessing and also we’d celebrate a virgin or saint’s month and such. It was something very normal.” As with other participants, the sense of obligation and being required to participate in religious practices is noted.

Culture

Cultural practices embedded in Catholicism also formed part of these participants’ religious education. Over one third of the participants (n = 23) indicated that cultural practices shaped their religious values while growing up. Catholicism informs daily lives in many Latin American societies, and is frequently a taken-for-granted feature of culture, as two men noted, “I was born in the Catholic religion” and “Mexicans are Catholics.” Religious celebrations like the posadas, a Mexican Christmas celebration to reenact Mary and Joseph’s struggle to secure shelter and food; town saints’ celebrations; Holy Week Stations of the Cross; baptisms; first communions; and weddings are all ceremonies in which many participants took part. George, born in Mexico City and currently living in Chicago, states: “In my hometown, people were very Catholic. They had dances and meals for the town’s little Saint. … The town had a little church for the Saint, so they have festivities for him with fireworks.”

Attending church on Sundays with one’s family is the tradition most participants remember. Mateo points out how Sunday mass, along with other Catholic traditions, are part of the social norms and moral principles, and in this case, of Mexican mainstream society. “Go to church every Sunday, confess and do communion, and then Catechism, and so on and so forth. … We’d do it because we had to. But also because it was the culture, the tradition, the social and moral norms of a family.”

The influence of Catholicism in culture and daily lives is not unique to those raised in Latin America. Participants raised in the United States also spoke of similar experiences. Hernan, for instance, grew up in California and despite his parents not practicing Catholicism, he took part in many religious ceremonies. He recalls: “As part of the tradition, we all had to go to Catechism every Saturday, and we’d have to make our communion, our confirmation.”

Levels of Participation and Commitment

The level of religiosity or level of participation and commitment to Catholicism during childhood varies among participants. Based on participants’ accounts, we created three levels: high, moderate, and low. The levels of religiosity varied based on two of the three different religious dimensions: participation in religious services and commitment. Affiliation was not considered since all of our participants were Catholics.

Those in the highest level of participation and commitment expressed a desire to learn about their religion and enjoyment of church-related activities; 10 participants were classified in this category. As children, they actively attended church, voluntarily belonged to church-related groups (e.g., choir, youth group), and felt good about their religious experiences. Mateo and his family, for example, attended church every week and received all the Catholic sacraments (e.g., confession, communion). He was very active in a youth group and the choir.

Similarly, Adrian recalls his excitement preparing for his first communion in his native Mexico. “They’d take me to church every Sunday. I loved it, because it meant going out and getting popcorn. I really liked the church we used to go to, so I said to my parents, ‘I want to do my first communion there.’ They told me it was too far. I didn’t care. For one whole year, I biked to catechism after school to do my first communion.”

Most participants (n = 45) experienced moderate levels of participation and commitment during childhood. Generally, they went to church every Sunday, did not express enjoyment of religious events, and some of them attended Catholic schools. Their involvement was inspired by tradition, social norms, and obligation, unlike those with high levels, who enjoyed and sought out church activities. This involvement included attending Sunday mass and making their first communion and confirmation. As Eduardo puts it: “It was really a major component of growing up. I don’t think it was very important, but it was something that I had to go to church every Sunday. . . it was boring and I wasn’t getting anything out of it.”

Finally, 10 participants experienced a low level of participation and commitment. Although these individuals grew up in self-proclaimed Catholic families, their Catholicism was based on the generalized cultural practices and traditions, in societies where Catholicism is the religion of the majority and frequently taken for granted. Their attendance to mass and participation in other ceremonies were sporadic and lower than those in the moderate category. Isidro, for instance, grew up in California with his mother. He was baptized Catholic, but only attended church on a few occasions: “I remember having my grandma take me to church for Easter … we didn’t grow up with the church.”

Adolescence

We refer to adolescence as a developmental period, rather than as a particular age group, loosely encompassing teenage and young adulthood years. In this period, most of the Latino GBTs interviewed came to terms with their sexual orientation and some also with their public sexual identities. In addition, many of them, as many adolescents do, began a process of separation from the family. For these participants, such process is made more difficult by a conflict between their sexual orientation and their families, peers, religion, and the larger society. In this sample, 37 individuals (57%) reported experiencing a conflict with Catholicism. The conflict stems from the Catholic Church’s condemnation of homosexuality. This led some participants to abandon Catholicism or to stop attending church, either temporarily or permanently.

Renato grew up in a very small town in Puerto Rico, where, according to him, most of the residents were Catholic. When he was in his teenage years, he was “kicked out” of the church after revealing his sexual orientation to the priest. He said: “I had homosexual thoughts at the time, and finally I talked to my minister and told him I was having these thoughts, and I got kicked out of the church for having these thoughts.” Similarly, Gonzalo grew up in a “very closed and very conservative” small town in Mexico, in which “you see a church on every street corner.” When he was a child, his mother volunteered him to be an altar boy. For Gonzalo, the experience was “suffocating, hypocritical, tense, superficial, but I wasn’t admitting it. … I was taught not to question the church.” As his homosexual desires became clearer, he began suffering a painful internal struggle. “Finally I started thinking of being gay … I went into a huge depression, because I felt that I was going to hell.” Gonzalo felt he could not do his usual church and school activities. He even became suicidal. “I knew that I was gay. The church said that if I was gay, I was going to go to hell. I was so fucking afraid of hell I wouldn’t do anything.”

Some participants, like Gonzalo, recount feeling depressed, ashamed, and guilty when they, as Catholics, began exploring their sexuality. Ramón’s excerpt illustrates the common contradictory emotions of guilt and desire. “I met this guy, I was 17 and he was 21. Then the feelings of guilt started. ‘Oh this is bad, I’m condemned, I’m going to hell.’ But when I was in the moment, ‘Oh, it was hot!’ The moral hangover came later. It was horrible because you’re putting more baggage on you.”

Adulthood

In adulthood there is a significant shift in religious affiliation as a result of both the resolution of the conflict experienced in adolescence and the development of adult lives as gay or bisexual men or transgender persons. On the one hand, only 26 out of 66 participants still identify as Catholic (two of them consider themselves Catholic, although they have also joined other religious groups or practices). Nearly all of these individuals moderately or highly participated and were committed to Catholicism during their childhood. On the other hand, 40 participants left the Catholic Church in adulthood. Most of them had low to moderate levels of participation and commitment to Catholicism as children. As indicated in Figure 1, Figure 8 converted to Protestantism and 8 to nontraditional religions or spiritual groups (e.g., Buddhism, meditation, Hinduism), while 27 indicated no affiliation or did not provide that information. Two participants identified with multiple religious and spiritual groups. Both of them said they were Catholics. One also identified as a Protestant, and the other as a Protestant who practices meditation, hence, the total of non-Catholic adults is 69. In this section, we describe participants’ current religious affiliation, how they addressed their conflict with Catholicism, their transition to other religions, and their current levels of religious participation and commitment.

The Catholics

Twenty-six of the 66 participants (38%) who grew up Catholic remained Catholic as adults. Almost all of these individuals experienced high or moderate levels of participation and commitment to Catholicism in childhood. More than half (n = 14), however, experienced a conflict between their sexual orientation and their religion during adolescence. As adults, they all have different positions towards Catholicism. Some do not question Catholic teachings, others justify their involvement through their own interpretations of the teachings following some “remedial work,” while others criticize but still affiliate with Catholicism. As expected, levels of participation and commitment vary among all the adult Catholics.

High levels of participation and commitment

Eleven of the 26 participants still identifying with Catholicism report a high level of participation and commitment to their religion, reflected mainly by their regular church attendance. Gabriel, for instance, attends church every Sunday in San Francisco. “I still go to a Catholic church on Sundays. I love going to church … It’s part of a cultural tradition.” For the most part, those participants who are highly involved have also reconciled their sexual orientation and their religious beliefs by either separating their own sexuality from their religious beliefs, or by reinterpreting Catholicism in a homo-positive manner. Jimmy illustrates the former. Weekly, he goes to church in a Mexican neighborhood on Chicago’s south side: “First of all, the priest obviously doesn’t know that I’m gay. And he does not have to know. I have no need to go and shout to the church that I’m gay.” Implicit in the narratives of Jimmy and others is remedial work that distinguishes between church and God. One cannot hide anything from God, who is perceived as being omnipresent, and unconcerned with one’s sexual orientation. One, however, can hide aspects of the self from the church (e.g., priest, lay members), which is perceived as a human-made institution (as opposed to God-made); that is, human like the self.

Diego’s remedial work consists of reinterpreting church teachings after reading the Bible and other religious books. He has concluded that, “there’s really nothing in there that leads me to feel that homosexuality is a sin.” Thus, religion is still his source of support and strength: “In times of desperation I always have my religion to fall back on. I’m confident that my prayers will eventually be answered.”

Moderate levels of participation and commitment

We categorized 10 participants as having a moderate participation and commitment to Catholicism. They claim their faith, pray, and read religious or spiritual books, but attend church only when they “feel like going” or on a sporadic basis. Josué said he goes to church “every once in a while,” but considers himself a confirmed believer, “I’m a very Catholic person, I’m a believer. I have a strong faith in God.” Lucas, born and raised in Colombia, attended Catholic colleges but does not think of himself as a practicing Catholic: “I never practiced as you should, but I’m Catholic. I believe in God and I’m always in contact with God.” Thus, although he identifies as a Catholic, he rarely participates in church or religious activities.

Some of these participants have not fully reconciled their sexual orientation and the Catholic Church’s position on homosexuality. Victor, for instance, knew that he was not accepted by his religion and as a teenager he would pray not to be gay. Currently, he still feels rejected, but maintains his Catholic faith and feels “closer to God.”

Low levels of participation and commitment

Only three participants fall under this category. These Latino GBTs, while thinking of themselves as Catholics and believing in God, participate in religious events only as dictated by tradition and major life events, such as weddings, baptisms, and funeral services. In the words of Pedro, a 30-year old gay man born in United States, “I go once in a while to mass and things like that, but I have never made it an integral part of my life. Yes, I go to church whenever somebody’s getting married, whenever I feel like going to church, but it’s something that I’ve never seen that has to be in my life.”

Among this group, there is no observable remedial work, which could be attributed to their low levels of participation and commitment. That is, their participation in church and commitment to Catholicism is not high as to question their homosexuality and religious beliefs.

The Protestants

Eight (12%) of the 66 participants who were raised Catholic converted to Protestantism in adulthood. They have joined different Protestant denominations, such as the Metropolitan Community Church, the Pentecostal Church, United Church of Christ, and Jehovah Witnesses. Participants in this group share three characteristics. First, all of them expressed conflict between Catholicism and their sexual orientation, and were able to reconcile their religious beliefs and their sexuality to a varying degree. Second, as children, most of them only maintained a moderate level of participation and commitment to the Catholic Church, which could help explain their conversion. Third, all of them are currently moderately or highly attached to Protestantism, which is expected because of their relatively recent conversions.

Renato lives in the Bay Area and is very active in the United Church of Christ. He left Catholicism, “because of what that church said, not because of what I felt, not because of what I believed.” Renato does volunteer work at his current church and is openly gay in the church. “My spiritual life has really brought me a lot closer at a spiritual level than I think I had been before.” Likewise, Gino, who belongs to an Evangelical church, maintains his criticism of the Catholic Church, “labels belong on cans, not on people. … [Protestants] love everybody, but [Catholics] criticize non-baptized persons.”

High levels of participation and commitment

Three individuals are highly committed to Protestantism and actively participate in religious events. Ramon, for example, joined a Pentecostal church in Chicago while married to a woman. Besides participating in church activities, he prays regularly and feels a deep connection with God. Renato, a Puerto Rican living in San Francisco, is a unique case. He is a member of the United Church of Christ and is one of the most religiously involved in the sample. “I have ended up becoming part of many different committees. So, for example, there is the Coalition of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Concerns, and I’m in the council of the coalition. I help in deciding what the Coalition’s priorities are going to be for the year and so on. … I belong to eight different committees.”

Moderate participation and commitment

Five participants fall under this category. They may attend church with some regularity, but may not engage in other religious activities. However, some of these individuals have been searching for churches in which they feel comfortable and welcomed. Eric attended a Metropolitan Community Church in Chicago, in which he was highly involved, becoming a delegate of the church for five years. He decided to take a sabbatical from his church two years ago due to the resignation of his pastor.

In the Bay Area, Gino attends an Evangelist Protestant church every Sunday in which he feels very welcome: “You can be gay, you can be a heroin addict, you can be an ex-alcoholic, you can be anything. Just go in there, they’re going to love you, it’s a really good church.”

Other Religions or Spiritual Groups

Eight of the 66 participants raised Catholic report joining other non-Judeo Christian religions or spiritual groups as adults. Those religions include Buddhism, Hinduism, yoga, meditation, rebirthing, Condomblé-Santeria, and Native American practices. There are four patterns among the Latino GBT individuals in this group. First, most of them experienced low to moderate levels of participation and commitment to Catholicism during childhood. As with those who converted to Protestantism, those low levels of involvement may have contributed to their separation from Catholicism. Second, all eight respondents currently maintain a high level of participation and commitment to their religious and spiritual lives. Third, in their teenage years, almost all of them experienced a conflict between their religion of origin and their sexuality. Fourth, almost all of these participants reside in San Francisco. This suggests the existence of a diverse religious environment, which may be more conducive to exploring various religions than in Chicago. As Vladimir puts it, “I encountered so many beliefs and cultures.” He moved to San Francisco eight years ago. Since then, he has been learning about yoga, meditation, Buddhism, and Islam.

In his early adult years, Gonzalo joined a Catholic monastery in New York. Gonzalo, who currently resides in San Francisco, recalls that his religious upbringing was very strict in Mexico. He was an altar boy and felt that he could not question religious teachings. While in the monastery, however, he came to terms with his homosexuality, which led him to renounce Catholicism and embrace Buddhism and Hinduism.

Now I realize that what I was taught was wrong, that it affected me psychologically … I was able to overcome my fear of the Catholic Church and teachings about homosexuality. Almost immediately, about a week later, I accepted myself for being gay. I told myself, ‘I’m gay and I don’t care.’ I used the word gay for the first time. … After accepting, I internalized that the Catholic Church is not everything and that I don’t agree with what I was taught about homosexuality. … I don’t consider myself Catholic anymore.

Marc found the acceptance he was looking for in Buddhism, which he has practiced since 1994: “I feel comfortable in this religion because I’m accepted as I am. I don’t feel rejected and it doesn’t make me feel depressed.”

Unaffiliated and Unspecified

The last group is compromised of 27 participants (41%); 11 of them report no current religious affiliation and 16 did not provide sufficient data to ascertain their religious or spiritual practices. As children, the majority maintained a moderate level of commitment to, and participation in, Catholicism. In their adult lives, as expected, the general level of participation in and commitment to religion or spirituality is low, as reflected by the limited involvement in religious practices or activities and the lack of religious affiliation. Part of it may be attributed to a rejection of institutionalized religion, which is perceived as disapproving of homosexuality. As expressed by Rigoberto: “My God knows that I’m gay and my God knows that I have a partner, so I don’t need to battle it out in some church.”

Some of these participants, nonetheless, hold a belief in God, pray, attend retreats, and read books for spiritual development. Pablo, for example, was raised by a father who explicitly rejected any religious practices. As an adult, he attended a religious retreat, which sparked his spiritual development: “It wasn’t until I went to this religious encounter that I got in touch with Christ, and realized how important the relationship is.” However, he does not indicate belonging to any religion or group.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to analyze the role of religiosity and spirituality in the life course of Latino GBTs who grew up as Catholics. Through the narratives of 66 life history interviews, we explored the religious and spiritual trajectories of these individuals. According to literature on human development, there is an expected sequencing and timing of life events (Elder, 1985; Hareven, 1986), which is often not the norm for GBTs (Cohler et al., 1998). The religious trajectory we found in our sample mirrored the developmental stages of childhood, adolescence, and adulthood.

During childhood, and similar to other cultures, our participants discussed how their religion was inculcated by family and culture. Due in part to gender roles and social expectations, mothers and grandmothers serve as the main providers of religious education and moral values. Catholic schools and community cultural practices, such as town patron festivities and Holy Week celebrations were mentioned as sources of religious education. Notably, this linkage between culture and religion is so pervasive that many individuals equate being Latino with being Catholic.

In adolescence, with the realization of a homosexual identity or the adoption of a GBT identity, religious trajectories were often altered. As other studies have shown, a transition occurs during the teenage or young adulthood years, which also corresponds to the coming out period for these participants (Herdt & Boxer, 1993; Rodriguez & Ouelette, 2000; Savin-Williams, 1998; Schuck & Liddle, 2001). As in previous research (Barret & Barzan, 1996; Newman & Muzzonigro, 1993; Ritter & O’Neill, 1989), our participants described this period as difficult and conflictive, in that they tried to reconcile their sexuality with a religion that views homosexuality as sinful and unacceptable. Individuals’ identity as good and moral beings is questioned and weakened due to traditional Catholic religious values. Some participants experienced rejection from their churches, as well as feelings of shame, guilt, and depression due to this conflict. Moreover, this conflict may be particularly intense because religion is tied to family and social practices. Thus, the conflict is not only about religious values, but also the individual’s position in the family and the wider society.

In adulthood, a resolution to the conflict between religion and sexuality occurred for most participants, as they developed their individual lives as GBTs. However, resolutions varied, ranging from staying in their church to abandoning religion, as has been found in other studies (Bevins & Cole, 2000; Idler et al., 2001; Kimble & McFadden, 1995; Pargament, 1997). The resolution of the conflict has led to four different paths: 1) remaining Catholic; 2) joining other traditional religions or denominations; 3) joining nontraditional religions or spiritual groups; and 4) abandoning organized religions. The diversity of possible resolutions that we found parallels that in other studies (Idler et al., 2001; Schuck & Liddle, 2001).

In the first path, those who remained in the Catholic Church resolved the differences between religious teachings and homosexuality in two different ways, both involving what Berger (1981) called a remedial ideological work. On the one hand, some individuals negotiate religious teachings against homosexuality by hiding their homosexuality (Berger, 1981; Fellows, 1996). These individuals attend religious services regularly, but are not openly gay in their churches and do not discuss their sexual life. On the other hand, some participants criticize religious teachings on homosexuality and decreased their levels of participation and commitment to Catholicism. These individuals attend church on very limited occasions, mainly for social events like weddings and funerals. Some participants in both subgroups make a distinction between the institutionalized religion and their personal spirituality and note that regardless of church dogma, their homosexuality is strictly between the individual and God. The current levels of participation in and commitment to Catholicism of all these individuals vary. This demonstrates that individuals utilized different ways to bring together their own identity and Catholic values, and in most of these instances, individuals “ideologically accommodate” their inconsistent practices and beliefs to create harmony (Berger, 1981; Thumma, 1991).

In the second path, participants abandoned Catholicism and joined other traditional religions or denominations that they perceived as welcoming of GBTs, such as the United Church of Christ that has a Lesbian and Gay Coalition, and the Metropolitan Community Church, which is an openly gay church. During their childhood, these participants had mostly moderate levels of participation and commitment to Catholicism, which probably facilitated the conversion to other religions. In their adolescence, all of them experienced a conflict between Catholicism and their sexuality. Currently, individuals in this group maintain moderate and mostly high levels of participation and commitment to their congregations. This is consistent with Rodriguez and Ouelette’s (2000) findings among Latino gay men in New York. The men in their study experienced a conflict with religion during their coming out process. All of those men abandoned their religion of origin and are currently members or attend the Metropolitan Community Church in that city.

In the third path, individuals abandoned Catholicism and joined other nontraditional religions or spiritual groups such as Buddhism, Hinduism, and yoga. Most individuals following this path reside in the San Francisco Bay Area, which suggests that it has a cultural climate more conducive to exploring non-Judeo Christian religions and spirituality. Latino GBTs in that area have been exposed to a new age movement in which meditation, spiritual groups, and Eastern religions are more widespread than in other parts of the country. Subsequently, San Francisco’s environment has probably affected participants’ varied explorations into nontraditional religions and spiritual traditions. In Chicago and the Midwest, non-Western religions and spiritual practices such as meditation are becoming a trend, but not to the same extent as in the San Francisco Bay Area. Moreover, as fewer participants have family ties in the San Francisco Bay Area than in the Midwest, participants are not pressured to remain in or choose religion because of their families’ influence. In addition, similar to those who converted to Protestantism, these individuals experienced low or moderate levels of participation and commitment to Catholicism during their childhood, which could have facilitated the transition to other religions in adulthood. All of these individuals maintain a high level of participation and commitment to their current religions or spiritual groups. This could be due to the fact that individuals have consciously searched and selected a new religion, rather than following family practices.

In the fourth path, participants do not identify with any organized religion or did not discuss it at all. Participants in this group perceived institutionalized religion as disapproving of homosexuality. Some have developed a posture in which spiritual life is disconnected from any formal religion. Congruent with that idea, all of these individuals have a low level of participation and commitment to religion or spirituality.

Despite that over two thirds of our sample abandoned the Catholic Church, religion and spirituality remain a significant force in the lives of Latino GBTs. Contrary to popular beliefs that GBTs are not religious, that they are oppressed by institutionalized religions, and that they completely reject institutionalized religions, the majority of our participants have a religious and spiritual life. Some rely on religion and spirituality for support and strength. Recall that this sample is made of activists, and hence, a number of these individuals are highly active in their respective churches or congregations. Religion has shaped the activism of these GBT individuals, and it is possible that the activism of these participants has affected their levels of religiosity and spirituality. Although we found little data supporting a causal connection between religion and activism, the levels of religious participation and commitment are relatively high in this sample compared to other studies that used the general Latino or GBT population. The activism or civic involvement of these individuals, with few exceptions, did not take place through their participation in church, but through community organizations working on HIV/AIDS and GBT issues. The life history data indicate that religious education during childhood and practice during adulthood may be providing the framework for activism and civic involvement in the form of values and attitudes.

Our findings make a significant contribution to the literature on religion and spirituality among GBTs. However, our findings must be evaluated in light of the limitations inherent in this study. First, we used a sample of Latino GBTs from two distinct U.S. locations, Chicago and San Francisco, who were raised Catholic. Thus, our findings cannot be generalized to other populations, settings, or individuals who were raised within other religions. The aim of our study, however, was not to make population-based generalizations from the data, but to explore and begin to understand the religiosity of GBTs raised Catholic. Second, due to the nature of the life history interviews, data on religion were limited or not available for some interviewees who did not comment on the subject. Moreover, for life histories we relied on accounts of past events, which could be filtered by individuals’ current experiences and views and by recollection biases. Future studies may include the larger population beyond activists (and perhaps nonactivists as well), to examine how formative religious education affects the depth of spiritual commitment Latino GBTs adopt as adults. Furthermore, more specific data are needed on religious involvement, commitment, and participation across the life course to understand differences between those raised Catholic, and those raised under other religions or spiritual traditions, and to further decipher the impact of religiosity on individuals’ health, personal relationships, sexual and gender identities, and civic involvement.

Despite the limitations, this study provides an in-depth view of the connection between religion and sexual identity. This relationship is complex and sometimes full of contradictions. For Latino GBTs, religion, and Catholicism in particular, is a source of values, morals, and strength. It is part of family, social life, and cultural identity. At the same time, religion may be a source of conflict, pain, and identity crisis.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a grant to Dr. Jesus Ramirez-Valles from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH62937-01).

REFERENCES

- American Religion Data Archive. Religion from GSS 2000. Chicago: American Religion Data Archive; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett R, Barzan R. Spiritual experiences of gay men and lesbians. Counseling & Values, 41. 1996:4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Berger BM. The survival of a counterculture: Ideological work and everyday life among rural communards. Berkley: University of California Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Bevins M, Cole T. Ethics and spirituality: Strangers at the end of life? Annual Review of Gerontology & Geriatrics. 2000;20:16–38. [Google Scholar]

- Catholic News. [Retrieved May 5, 2004];Vatican statistics claim 1.07 billion Catholics. 2004 from http://www.cathnews.com/news/402/18.html.

- Clipp E, Pavalko E, Elder G., Jr Trajectories of health: In concept and empirical pattern. Behavior, Health, and Aging. 1992;2:159–179. [Google Scholar]

- Cohler BJ, Hostetler AJ, Boxer AM. Generativity, social context, and lived experience: Narratives of gay men in middle adulthood. In: McAdams DP, de St. Aubin E, editors. Generativity and adult development: How and why we care for the next generation. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1998. pp. 265–309. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson MG. Religion and spirituality. In: Perez R, DeBord KA, Bieschke KJ, editors. Handbook of counseling and psychotherapy with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. Atlanta, GA: Emory University Press; 2000. pp. 409–433. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin N. Interpretative biography. Newbury Park, NJ: Sage; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon M. The sociology of religion in late modernity. In: Dillon M, editor. Handbook of the sociology of religion. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press; 2003. pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH. Perspectives on the life course. In: Elder GH, editor. Life course dynamics: trajectories and transitions, 1968–1980. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 1985. pp. 23–49. [Google Scholar]

- Fellows W. Farm boys: Lives of gay men from the rural midwest. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Flannelly LT, Inouye J. Relationship of religion, health status, and socioeconomic status to the quality of life of individuals who are HIV positive. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2001;22:253–272. doi: 10.1080/01612840152053093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama MA, Ferguson AD. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual people of color: Understanding cultural complexity and managing multiple oppressions. In: Perez R, DeBord KA, Bieschke KJ, editors. Handbook of counseling and psychotherapy with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2000. pp. 81–105. [Google Scholar]

- Galvan FH. Sources of personal meaning among Mexican and Mexican American men with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Multicultural Social Work. 1999;7:45–67. [Google Scholar]

- Gramick J. Prejudice, religion, and homosexual people. In: Nugent R, editor. Challenge to love: Gay and lesbian Catholics in the church. New York: Crossroad; 1983. pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hareven T. Historical changes in the social construction of the life course. Human Development. 1986;29:171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Herdt G, Boxer AM. Children of horizons: How gay and lesbian teens are leading a new way out of the closet. Boston: Beacon Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hinchman LP, Hinchman SK. Introduction. In: Hinchman LP, Hinchman SK, editors. Memory, identity, community: The idea of narrative in the human sciences. Albany: State University of New York Press; 1997. pp. xiii–xxxii. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkinson VA. Key factors influencing caring, involvement, and community. In: Schervish PG, Hodgkinson VA, Gates M, editors. Care and community in modern society: Passing on the tradition of service to future generations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1995. pp. 21–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt LL. The spirit of Hispanic Protestantism in the United States: National survey comparisons of Catholics and non-Catholics. Social Science Quarterly. 1998;79:828–845. [Google Scholar]

- Hyden L. Illness and narrative. Sociology of Health and Illness. 1997;19:48–69. [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL, Kasl S, Hays JC. Patterns of religious practice and belief in the last year of life. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2001;56B:S326–S334. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.6.s326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll-Dayton B, Krause N, Morgan D. Religious trajectories and transitions over the life course. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 2002;55:51–70. doi: 10.2190/297Q-MRMV-27TE-VLFK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimble M, McFadden SH. Aging, spirituality, and religion: A handbook. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, McCullough ME, Larson DB. Handbook of religion and health. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Levine DH. Religion and political conflict in Latin America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Lieblich A, Tuval-Mashiach R, Zilber T. Narrative research: Reading, analysis, and interpretation. Vol. 47. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer J. Levels of analysis: The life course as cultural construction. In: Riley MW, Huber BJ, editors. Social change and the life course. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1988. pp. 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Myers JE, Sweeney TJ, Witmer JM. The wheel of wellness counseling for wellness: A holistic model for treatment planning. Journal of Counseling and Development. 2000;78:251–266. [Google Scholar]

- Newman BS, Muzzonigro PG. The effects of traditional family values on the coming out process of gay male adolescents. Adolescence. 1993;28:213–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novitz D. Art, narrative, and human nature. In: Hinchman LP, Hinchman SK, editors. Memory, identity, community: The idea of narrative in the human sciences. Albany: State University of New York Press; 1997. pp. 143–160. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI. The psychology of religion and coping. New York: Guilford; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Peacock JR, Paloma MM. Religiosity and life satisfaction across the life course. Social Indicators Research. 1999;48:321–345. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Valles J, Diaz RM. Public health, race, and the AIDS movement: The profile and consequences of Latino gay men’s community involvement. In: Omoto AM, editor. Processes of community change and social action. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2005. pp. 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ratzinger J. The revolt of the religious orders. 1994;5:AD2000. [Google Scholar]

- Religion News Service. [Retrieved May 5, 2004];Pope urges new effort to curb ‘sects’ in Latin America. 2001 from http://www.cathnews.com/news/402/18.php.

- Ritter KY, O’Neill CW. Moving through loss: The spiritual journey of gay men and lesbian women. Journal of Counseling and Development. 1989;68:9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez EM, Ouellett SC. Religion and masculinity in Latino gay lives. In: Nardi PM, editor. Gay masculinities. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. pp. 101–129. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC. “… And then I became gay”: Young men stories. New York: Routledge; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Williams RC. Mom, dad. I’m gay: How families negotiate coming out. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Schuck KD, Liddle BJ. Religious conflicts experienced by lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotherapy. 2001;5:63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Sherkat DE. Sexuality and religious commitment in the United States: An empirical examination. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2002;41:313–323. [Google Scholar]

- Sherkat DE. Religious socialization: Sources of influence and influences of agency. In: Dillon M, editor. Handbook of the sociology of religion. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press; 2003. pp. 151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Smith DH. Determinants of voluntary association, participation and volunteering: A literature review. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. 1994;23:243–263. [Google Scholar]

- Thumma S. Negotiating a religious identity: The case of the gay evangelical. Sociological Analysis. 1991;52(4):333–347. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J, Musick M. Who cares? Toward an integrated theory of volunteer work. American Sociological Review. 1996;62:694–713. [Google Scholar]

- Wink P, Dillon M. Spiritual development across the adult life course: Findings from a longitudinal study. Journal of Adult Development. 2002;9:79–94. [Google Scholar]