ABSTRACT

The economic and human cost of suicidal behavior to individuals, families, communities, and society makes suicide a serious public health concern, both in the US and around the world. As research and evaluation continue to identify strategies that have the potential to reduce or ultimately prevent suicidal behavior, the need for translating these findings into practice grows. The development of actionable knowledge is an emerging process for translating important research and evaluation findings into action to benefit practice settings. In an effort to apply evaluation findings to strengthen suicide prevention practice, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) supported the development of three actionable knowledge products that make key findings and lessons learned from youth suicide prevention program evaluations accessible and useable for action. This paper describes the actionable knowledge framework (adapted from the knowledge transfer literature), the three products that resulted, and recommendations for further research into this emerging method for translating research and evaluation findings and bridging the knowledge–action gap.

KEYWORDS: Suicide prevention, Youth, Actionable knowledge, Knowledge to action, Knowledge–action, Research-to-practice, Implementation, Knowledge transfer, Public health

The economic and human cost of suicidal behavior to individuals, families, communities, and society makes suicide a serious public health concern, both in the United States and around the world. In the US, it is estimated that deaths resulting from suicide create a financial burden of over 26 billion dollars a year in medical costs and work loss [1]. Suicide is also one of the most common causes of death among young people in the US. It is the second leading cause of death among 25–34-year-olds and the third leading cause of death among 15–24-year–olds [2]. In 2011, nearly 16 % of high school students (typical age range 14–18 years old) reported that they had seriously considered suicide in the past year [3], that is, about three students out of a typical classroom of 20 [4].

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines suicidal behavior as including (1) suicidal ideation (thoughts of harming or killing oneself), (2) suicide attempt (a nonfatal, self-directed potentially injurious behavior with any intent to die as a result of the behavior), and/or (3) suicide (death caused by self-directed injurious behavior with any intent to die as a result of the behavior) [5]. Historically in the US, suicide has almost exclusively been addressed by providing mental health services to people already experiencing suicidal thoughts or behavior. While services such as therapy and hospitalization are critical for those who are already affected by suicide, they do not prevent suicidal thoughts or behaviors from happening in the first place (primary prevention). In addition, there are often too few mental health services in communities to address all youth who are depressed or are struggling with suicidal thoughts or behaviors, and even when such services are available in communities, access, cost, and stigma are often barriers for youth needing these services [6].

A public health strategy fills the gaps in traditional, clinical approaches to treating suicidal behavior through suicide prevention (in particular, primary prevention) which focuses on using a population approach to improve health on a large scale—not just the health of individuals. While suicide may often be thought of as an individual problem, families, communities, and society also are adversely affected. For example, when a youth dies from suicide, not only is a valuable life lost, but this loss can impact the mental health of family and friends, put other youth in the community at higher risk through “copycat” suicides, and result in a loss of potential productivity/economic contributions to society [7]. In order to prevent suicide before it occurs, public health aims to reduce people's risk for suicidal behavior at multiple levels of the social ecology (at the individual, relationship, community, and societal levels) [8]. For example, public health approaches may aim to address risk for suicide at the individual (e.g., prevention and treatment of substance abuse), relationship (e.g., improving sense of connection to family and friends to prevent feelings of isolation), community (e.g., changing social norms and reducing stigma, reducing access to means such as structural barriers around bridges), and societal levels (e.g., appropriate media coverage of deaths by suicide to prevent “copycat” suicides). Public health also aims to buffer risk with protective strategies (e.g., fostering connectedness through family and community support).

Suicide is closely related to other forms of violence (e.g., exposure to violence as a child is associated with suicidal behavior as an adult), as well as other health problems [9–11]. Collaboration across disciplines such as behavioral science, epidemiology, health, social science, criminal justice, business, media, advocacy, and education is, therefore, often a critical part of a public health approach to suicide prevention. Another key feature of public health's role in addressing suicide is its commitment to science by: (1) identifying the magnitude and scope of the problem and tracking and monitoring trends in suicidal behavior overtime, (2) identifying risk and protective factors for engaging in suicidal behavior, (3) developing and testing strategies that reduce risk for or protect against suicidal behavior, and (4) widely disseminating and bringing to scale those effective strategies to create population level change [8]. In the past 20 years, public health has come a long way in its ability to track and monitor suicide rates (surveillance systems), identify risk and protective factors (etiological research), and develop/test effective suicide prevention strategies (effectiveness research). While there is still a significant amount of important work to be done in all of these areas, one of the emerging challenges facing public health is determining ways to effectively disseminate and implement “what we know” about preventing suicide at a large scale to achieve population level impact.

KNOWLEDGE–ACTION GAP

The gap between research and implementation in practice has long been noted in the literature as a major barrier in achieving desired health-related outcomes [12–14]. While research on effective suicide prevention strategies is still in development [15], a gap persists between the emerging knowledge generated through preliminary studies and evaluations and the application of these findings to improve suicide prevention practice. There are a number of reasons why this knowledge–action gap exists [16]. For example, Dearing [17] identified a number of common mistakes made when disseminating research findings and strategies shown to be effective in research settings into practice, such as assuming that evidence matters in the decision making of potential adopters, substituting researchers' perceptions for those of potential adopters, and failing to distinguish between the different roles needed for successful dissemination. Therefore, in order for crucial research and evaluation findings to reach the broadest audience possible and be effectively and widely adopted, it is important to understand how to make these findings relevant and effectively disseminate, implement, and bring them to scale in a wide variety of contexts and settings.

The science and practice of bridging the knowledge–action gap can take many forms and serve many purposes. There are a number of different definitions and terms used to describe this process. In public health, it is typically referred to as translation or knowledge transfer and can include the translation and dissemination of specific pieces of research information or evaluation findings. In this paper, we use the terms and definitions for knowledge translation outlined by Graham et al. [18]. They describe the process of moving knowledge to action and propose a framework that divides the process into two distinct phases: knowledge creation and knowledge action. These phases are fluid, often occur simultaneously, and influence one another. In the knowledge creation phase, research and/or evaluation findings become increasingly refined and useful by synthesizing the findings of studies relevant to a specific question. Once knowledge is adequately refined, tools or products are developed to present it in a clear, concise, and user-friendly format. The action phase involves the process of dissemination and implementation, or broad application of knowledge. This process also includes activities related to adaptation, further evaluation, and sustainability. Both phases include communication and collaboration between the research/evaluation and practice fields [18].

Further review of the knowledge translation literature reveals three knowledge transfer and exchange models that attempt to address the knowledge–action gap [19–21]. The producer-push model describes the traditional unidirectional flow of research or evaluation knowledge, which is pushed outward to the practice field [22–25]. Conversely, in the user-pull model, program implementers in the field attempt to pull knowledge from the best available research and evaluation findings. This is also described as the user-based model [22]. Finally, the exchange model is a hybrid of both models, focusing on a bidirectional exchange of research or evaluation knowledge between researchers and decision makers in the policy and practice fields. Decision makers (policy-makers and/or clinical decision makers/practitioners) help researchers and evaluators identify work that is more relevant for practice, and researchers and evaluators help decision makers in the policy and practice fields use research knowledge or evaluation findings in decision-making [26–28]. Creation of actionable knowledge is one emerging process that draws upon principles from the knowledge translation, transfer, and exchange literature for translating important research and evaluation findings and packaging them in a way that supports action to improve practice.

ACTIONABLE KNOWLEDGE

Broadly (and simply) defined, actionable knowledge is the creative intersection between what we know and putting what we know into everyday practice [29]. In the knowledge to action process described by Graham et al. [19], the development of actionable knowledge would be considered a key component of the knowledge creation phase, where research and evaluation findings are synthesized, distilled, and packaged in ways that are user-friendly and action oriented. As such, actionable knowledge helps to provide a bridge between important (but sometimes inaccessible) research or evaluation findings and action in practice settings. This bridge/connection has the potential to be a powerful tool for public health's work in improving suicide prevention practice, increasing program readiness for more rigorous evaluation and effectiveness research, and eventually ensuring widespread adoption of effective suicide prevention strategies to impact population health.

Actionable knowledge can be packaged in many forms, from simple, plain-language briefs to more elaborate skill-/knowledge-building exercises. For example, in public health, best available research on effective strategies for preventing transmission of the flu virus has been translated into clear, easy to understand, actionable messages [30–32], such as the importance of hand washing, sneezing into your elbow, and vaccinating those at highest risk for flu-related complications. This and other examples of actionable knowledge products provide opportunities for behavior change by offering clear guidance for action [27].

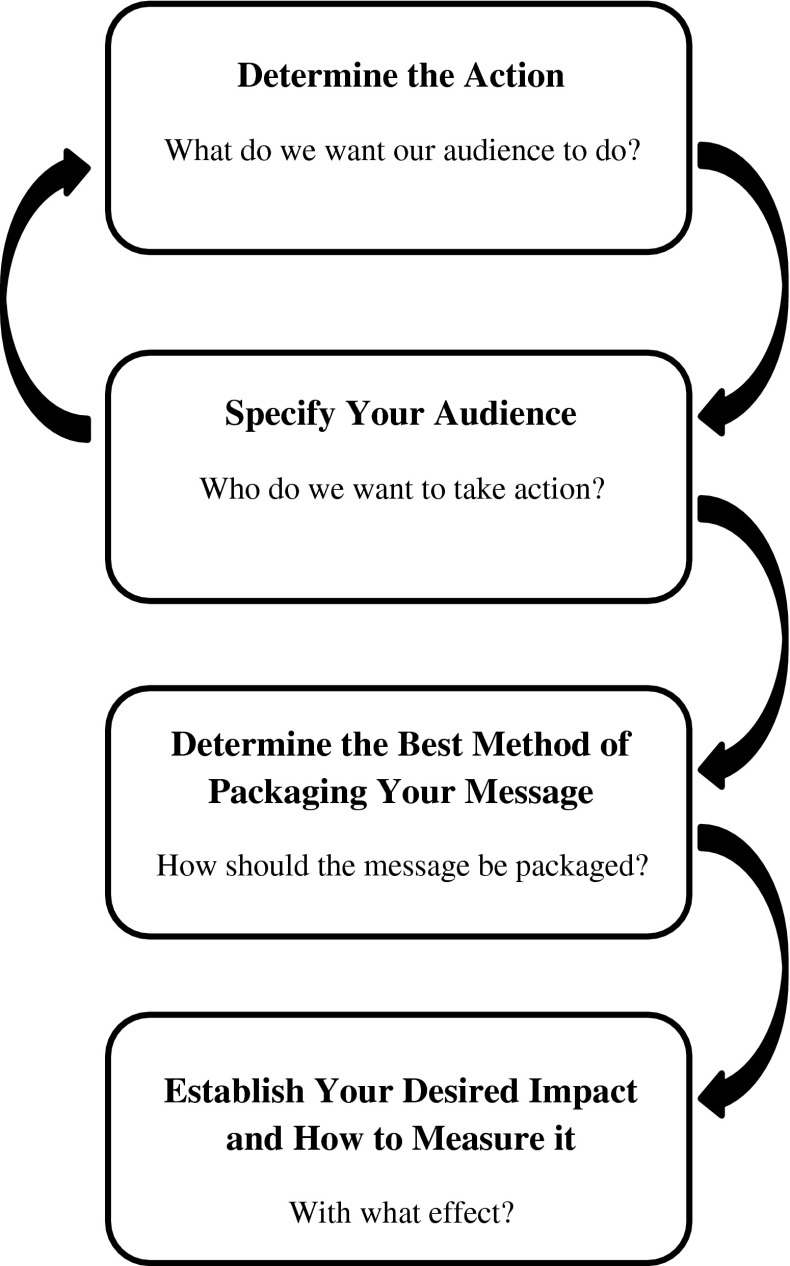

Another important characteristic of actionable knowledge is that it is based on the best available research and evaluation findings and, thus, simultaneously meets the expectations of the scientific community in terms of scientific rigor while also meeting the practical needs of practitioners and organizations [33]. In other words, actionable knowledge offers clear, compelling ideas for action backed by best available research and evaluation. The development of actionable knowledge can be a relatively systematic and comprehensive process. One framework for developing and packaging actionable knowledge is adapted from the knowledge transfer literature [28, 34]. The original version of this framework for knowledge transfer includes five key questions: (1) what is the message? (2) To whom (audience)? (3) By whom (messenger)? (4) How (transfer method)? (5) With what expected impact (evaluation)? The adapted framework for creating and packaging actionable knowledge (see Fig. 1) includes four key steps: (1) determine the action (“what do we want our audience to do?”), (2) specify your audience (“who do we want to take action?”), (3) determine the best method of packaging your message (“how should the message be packaged?”), and (4) establish what your desired impact is and how you will measure whether your actionable knowledge has had this desired impact (“with what effect?”). This adapted framework also draws upon key principles from the exchange model of knowledge transfer where bidirectional exchanges of information between end users and researchers are a priority. As such, it should be noted that emphasis is placed on engaging key stakeholders (including end users or the “audience”) at each stage of the process [26]. As a result, steps 1 and 2 of this actionable knowledge framework are often not linear. In many cases, the determination of “what” the desired action is and “who” the audience is occurs iteratively and in tandem. It is also important to note that the purpose of this adapted framework is to develop and package actionable knowledge in a way that is conducive to successful dissemination and implementation. This is an important part of supporting the transfer of research and evaluation knowledge into action, but purposeful dissemination and implementation activities are also necessary for this successful transfer to occur [19]. These dissemination and implementation strategies are beyond the scope of this framework.

Fig 1.

Adapted actionable knowledge framework for developing and packaging actionable knowledge. Framework adapted from Lavis et al.'s (2003) Framework for knowledge transfer

In applying this adapted framework, the first question that needs to be answered during the process of creating actionable knowledge is “what do we want our audience to do?” In some cases, the action may be clear, such as when a school needs specific, research-informed talking points for counselors to use when speaking with parents of at-risk youth. In other cases, the desired “action” may not be as clear, such as the general need in a community for translated research findings on a comprehensive suicide prevention strategy. Processes that help synthesize best available research or evaluation findings while, at the same time, considering the contextual realities and experiences of the audience [35, 36] can help determine which pieces of research or evaluation-based knowledge should be the focus for action. In other words, which research and/or evaluation findings are most relevant for the desired action? The next step of the actionable knowledge process (identifying the audience for whom actionable knowledge is being generated) is also important in refining the focus for action.

A key part of this next step involves engaging stakeholders from both research and practice to answer the question “who do we want to take action [37]?” As mentioned above, this often happens in tandem with the first step of the process and helps to ensure that actionable knowledge is being created for and tailored to those who are most in need of that information and/or could benefit most from it.

Ensuring that messages urging action are delivered in a way that is most appropriate and resonates most for the identified audience is a critical part of creating effective actionable knowledge. This step in the actionable knowledge process answers the question “how should the message be delivered so the audience is likely to act on the information?” For example, the language used to communicate the actionable knowledge should be appropriate for the intended audience (e.g., reading level, familiar terminology, etc.). Actionable knowledge should also be framed and packaged in a way that will be most conducive for successful dissemination, adoption, and implementation in the settings and with the audiences who are the focus for action. For example, creating online tools and resources to communicate actionable messages may be an appropriate method for packaging actionable knowledge if the intended audience has the skills and ability to access online tools and there is the capacity to share these online tools with this audience (dissemination). Online tools would also be appropriate if technical assistance resources and support are available to help apply the information from these online actionable knowledge products to local settings (implementation). If these factors related to dissemination and implementation are not in place, however, other methods of packaging actionable knowledge should be considered (e.g., paper-based tools, inclusion of information on where to find implementation support, etc.) to facilitate successful dissemination and implementation with the intended audience.

Finally, the last, critical step in the actionable knowledge development process helps answer the question “with what effect?” Determining the desired impact of actionable knowledge helps to identify the different intended purposes or uses of an actionable knowledge product. These include direct use (e.g., changes in behavior, policy, and practice), indirect use (e.g., changes in knowledge, awareness, and attitude), and/or tactical use (e.g., justification for decisions already made/made for different reasons) [28]. Knowledge translation is primarily focused on facilitating direct and indirect uses of knowledge, although it is important to be aware of potential unintended tactical uses when developing actionable knowledge. Determining the desired impact of a particular piece of actionable knowledge is critical in the actionable knowledge development phase to help determine the scope and focus of the actionable knowledge product [29]. It is also helpful for eventually measuring whether or not the actionable knowledge product, along with the dissemination and implementation strategies it is accompanied by, has achieved its desired impact. Evaluation findings can be used to improve the actionable knowledge products themselves, as well as their dissemination and implementation strategies, to strengthen the desired impact, as needed.

What follows are three examples where this actionable knowledge development process has been used to create products that may help bridge the knowledge–action gap in youth suicide prevention. Research and evaluation on the process and products created is beyond the scope of the current paper, but it is hoped that the case examples presented here will provide concrete examples of this important, emerging area of knowledge translation.

PRACTICAL EXAMPLES OF ACTIONABLE KNOWLEDGE IN SUICIDE PREVENTION

In an effort to help address the knowledge–action gap, the CDC and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) supported three Garrett Lee Smith Memorial Act (GLS)1 grantees to enhance the evaluations of their youth suicide prevention programs by using a public health approach. This included studying youth suicide at the population level, focusing on primary prevention, and using quantitative and qualitative youth suicide data at the local and community levels. What follows are descriptions of the key findings and lessons learned from each of these enhanced program evaluations (“enhanced evaluations”), and the actionable knowledge framework used to make these findings relevant and actionable for use by practitioners in the field of suicide prevention.

Tennessee lives count

Between 2005 and 2008, the Tennessee Lives Count project (TLC, an initiative of the Tennessee Department of Mental Health) provided brief gatekeeper training (i.e., training to identify and refer individuals who are at risk for suicide) to more than 18,000 adults working with youth and young adults in education, child welfare, juvenile justice, health, and higher educational settings. The authors from Centerstone Research Institute worked with staff from the TLC project to conduct an initial evaluation of TLC's gatekeeper training program, as well as TLC's enhanced evaluation through the CDC and SAMHSA intra-agency agreement to address additional important questions.

Prior research has shown that immediately after gatekeeper training, participants showed increased knowledge (actual and perceived), improved attitudes about suicide prevention, increased confidence (self-efficacy beliefs), and skills to help at-risk individuals [38–42]. Little research exists, however, on whether increases in gatekeepers' knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and skills lead to actual gatekeeper-helping behaviors, nor is there much research on the long-term effectiveness of gatekeeper training in preventing suicidal behavior. The broad purpose of the TLC-enhanced evaluation was to expand understanding about gatekeeper training among several specific populations. The enhanced evaluation consisted of three studies: (1) a 6-month follow-up to monitor long-term gains after one-time gatekeeper training [39], (2) a study of factors that predict gatekeeper-helping behaviors [43], and (3) a descriptive study of gatekeeper-helping behaviors as they naturally occur in the child welfare system. Initial outcomes from the enhanced evaluation were further explored, and additional lessons learned were gathered in a separate longitudinal study of gatekeeper training for staff of juvenile justice centers. Focus groups were also used to talk directly with participants about what aspects of training were most helpful and how gatekeeper training programs for staff serving high-risk youth could be improved.

The TLC-enhanced evaluation revealed a number of important findings related to gatekeeper training. Quantitative findings indicated that long-term gains from training are not guaranteed [39], and prior and ongoing training can make a difference [43]. At pretest, participants with prior suicide prevention training had more perceived knowledge about suicide prevention, more self-efficacy for engaging in gatekeeper behavior (identifying and referring at-risk youth), and more favorable attitudes (i.e., that suicide is preventable). These gatekeepers also maintained their training gains more than other gatekeepers. As such, ongoing training may have a booster effect. Previously trained gatekeepers identified 2.4 times the number of suicidal youth as those with no prior training, even after accounting for the child-serving system in which they worked. Quantitative findings also revealed that gatekeepers' perceived knowledge matters long-term. For every point increase on a measure of perceived knowledge (perceived knowledge of warning signs and how to help at-risk youth), trainees identified 1.5 times the number of suicidal youth [43].

Qualitative findings also revealed a number of important lessons learned. For example, the enhanced evaluation revealed that “unintended” recipients of training (e.g., secretaries, cafeteria workers, and janitors) who were present during training sessions but were not specifically targeted also benefited from training. In addition, findings indicated that talking about “local resources” when they are unknown or unavailable may be unproductive, and gatekeeper trainees forget about community resource and referral options over time. For a complete list of lessons learned, see Table 1. Of primary importance, data collected from the follow-up longitudinal study of gatekeeper training for staff of juvenile justice centers suggested that it is critical to make the training material personally relevant for gatekeepers and develop “customized” working knowledge of how to apply the training in their specific work or community setting. For many gatekeepers, such knowledge included discussing how to implement the training with key leaders/supervisors, discussing how suicide prevention response techniques would be different as a result of the training, and how these could be applied within existing policies and protocols in the organization [44].

Table 1.

Tennessee Lives Count enhanced evaluation key lessons learned and recommendations

| Phase | Lessons learned | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Pretraining | Gatekeepers benefit from training in different ways depending on their skills, roles, and context | Determine roles of gatekeepers within their organization/system and match training to their skills, roles, and context |

| TLC's “unintended” recipients of training—secretaries, cafeteria workers, and janitors benefited from training | Plan to train more than the “usual suspects.” Support staff can be just as crucial as guidance counselors, social workers, and so on | |

| Organizational policies and procedures for suicide-related incidents matter. Sometimes gatekeeper curricula contradict local policies and norms | Review current policies and procedures and modify training as needed | |

| Organizational barriers are common (e.g., senior leaders, supervisors, and managers may lack knowledge on suicide prevention) | Identify and address organizational barriers | |

| The target population matters. At-risk populations (foster care, juvenile justice) have a higher likelihood of suicide risk | Identify target population and choose the gatekeeper training that fits it best (i.e., a thorough training specific to the at-risk population) | |

| Training | Gatekeepers will use gatekeeper skills at work, but they will also use the skills with family members, in the neighborhood, and in the broader community | Talk about the opportunities for and the differences between suicide prevention at work and at home |

| Talking about “local resources” when they are unknown or unavailable may be unproductive | Have local resource sheets available. If they are lacking, get input from trainees on local resources, and assist them in developing a local resource guide | |

| Individual roles within organizations matter. Due to job expectations, concerns about liability, etc., gatekeepers may be reluctant to help or may even be discouraged from helping | Talk about individual roles in suicide response and how individuals can work effectively as a team | |

| High-risk youth have complex needs. For instance, youth in state custody may seek unconventional means (glass, shoe strings) for harming themselves or attempting suicide | Address complex issues for high-risk youth and ways gatekeepers can most effectively respond | |

| Post-training | Skills from brief gatekeeper trainings do not last long-term. Brief “booster” trainings may be needed to increase skills | Schedule “booster” trainings at 6-month intervals to increase skills of new trainees and to maintain skills of prior trainees |

| Trainees forget about community resource and referral options over time | Work to increase access to and awareness of your community resource and referral options (e.g., bulletin boards, links on company website) | |

| Due to multiple staff contacts, turnover, and the general complexity of suicide-related events, linking results to the gatekeeper instead of the youth distorts results | Reflect as a team. How are we helping each other use our gatekeeper helping skills? Evaluate training success based on the organization's helping process, not solely on individual gatekeeper response | |

| Organizational barriers affect adoption of new gatekeeper training skills (e.g., organizational policies that make identification and referral difficult) | Identify and reduce or eliminate organizational barriers (e.g., work with organizational leaders to align policies with successful identification and referral) |

In order to share these lessons learned with the field and facilitate the translation of evaluation findings for practice, researchers from the TLC-enhanced evaluation created the Gatekeeper Training Implementation Support System (GTISS; www.gatekeeperaction.org), an online toolkit to assist community members and organizations in planning, implementing, and evaluating gatekeeper trainings. What follows is a description of the development of this actionable knowledge product.

Step 1: what do we want our audience to do?

When considering which findings from the enhanced evaluation should be the focus of the TLC actionable knowledge product, outcomes from the evaluation and findings from focus groups with gatekeeper training participants were considered to ensure the balance of research and practice in prioritizing findings to be made actionable. Both the enhanced evaluation results and focus group findings suggested that gatekeeper programs should be tailored to their audience in order to be most effective, although a “tailored” approach to gatekeeper training in terms of customizing the training content alone may not be enough for successful implementation. It became clear that additional implementation process and supports were essential. For example, the enhanced evaluation revealed that gatekeepers need opportunities to think through the training content, discuss the information with supervisors and peers, consider the training content in relationship to existing policies and protocols, and receive feedback from community members/managers on the success of the training initiative. In essence, gatekeepers not only need to hear information in training that is unique to their population, but must also process the information so that the way in which the information is used becomes contextualized to their unique setting as a gatekeeper. Through this process, gatekeepers may develop internal working models of how to apply the training in real-life situations in their work and/or community environments. This process may assist gatekeepers in not only gaining knowledge about suicide and experiencing changes in attitudes about suicide, but also actually using the information to identify, refer, and follow-up with suicidal youth. Also, the evaluation identified that a number of system-level and individual-level barriers may impede the use of skills learned from gatekeeper training, and typically gatekeeper training curricula do not have sufficient implementation guidance to adequately address these barriers [40]. The results also illustrated that there was valuable information to be gleaned from existing practices such as how child welfare and juvenile justice staff identify suicidal youth and work with others in their systems to help youth. From this information, researchers from the TLC-enhanced evaluation developed recommendations to address these individual-level and system-level factors (barriers and facilitators) that play critical roles in the success of individual and organizational responses to suicide. These key lessons learned and corresponding recommendations are summarized in Table 1 and make up the “what” of the TLC actionable knowledge product.

Step 2: who do we want to take action?

The audience for the GTISS, as a whole, is quality improvement directors, organizational leaders, program evaluators, state suicide prevention leaders, gatekeeper trainers, and program managers overseeing programs serving high-risk youth. The tools for the GTISS are specified by audience, with half of the tools designated for organizational-level use and half of the tools designed to be used by gatekeepers themselves.

Step 3: how should the message be packaged?

When deciding how the TLC lessons learned and recommendations (actionable knowledge) should be packaged, researchers and practitioners involved in the TLC evaluation drew from their experiences identifying, implementing, and evaluating gatekeeper training programs in a variety of different settings, with a number of different populations. They also took into account the resources available for the development of the actionable knowledge product (e.g. staff time, budget, etc.). Through this process, the TLC team developed the GTISS, which is the “how” or the method through which actionable knowledge is packaged for the primary audience. The system provides accessible, online tools (the “how”) for assisting organizations, trainers, and program managers in tailoring gatekeeper training experiences to specific settings/contexts and overcoming common system-level and individual-level barriers to implementation. This actionable guidance is organized into five separate stages with corresponding tools for both organizations that work with youth (i.e., schools, social service agencies, and state departments of juvenile justice or children's services) and individual gatekeepers within those organizations. Each stage has its own electronic presentation template created based on lessons learned from the TLC project, evaluation findings, and input from TLC participants. These slides can be easily incorporated into existing gatekeeper training sessions. In addition, each stage is accompanied by tools, templates, checklists, and surveys, which assist local leaders in tailoring gatekeeper training to their organizations. Local leaders are encouraged to: (1) consider these critical participant, organizational, and system factors; (2) determine how they apply in their local contexts; and (3) adapt and use the tools to guide future implementation.

Step 4: with what effect?

The GTISS was created to improve the selection, implementation, and evaluation of gatekeeper training programs. As such, its primary purpose is for what the knowledge translation literature terms direct use (use for behavior change) [28]. As mentioned previously, Table 1 outlines the five stages of the GTISS and the tools associated with each stage that were developed to achieve this desired impact.

Future evaluation of the GTISS is needed to ensure the effectiveness and feasibility of the tools and resources, and to learn more about dissemination strategies and implementation supports needed to effectively apply the tools and resources for action in practice settings. More specifically, future evaluations of the GTISS should focus on questions such as: does the GTISS improve implementation and effectiveness of gatekeeper training programs? If so, how? Which dissemination strategies appear to increase online “traffic” and how have organizations/websites “linked” to the GTISS website? What additional implementation supports are needed to successfully apply the GTISS tools? Answers to these questions will help to determine whether and how an implementation support system such as the GTISS can help to translate evaluation findings into action to improve suicide prevention practice.

Life is sacred native youth suicide prevention program

The Life Is Sacred Native Youth Suicide Prevention Program is a collaborative youth suicide prevention program facilitated by the Native American Rehabilitation Association of the Northwest, Inc. (NARA-NW). It combines the efforts of all nine of Oregon's federally recognized Tribes as well as the Native American student group at Portland State University, the Portland Indian Elders Support Group (PIESG) from the Portland Metropolitan Area, and a range of youth services and activities at NARA-NW. The program is designed to link traditional spiritual and cultural beliefs with known best practices in youth suicide prevention. In doing so, it is raising community awareness, mobilizing and training local and state resources, and strengthening essential protective factors with the goal of reducing youth suicide in Native American communities throughout Oregon.

The overarching goal of the Life is Sacred-enhanced evaluation was to provide actionable information to help staff working with American Indian/Alaskan Native (AI/AN) youth better understand the risk and protective factors associated with suicidal thoughts and behavior, and to provide guidance for future youth programming. Before this effort began, such data did not exist for Oregon Tribal communities. In fact, very little research existed at all on protective factors for suicide among AI/AN youth, especially AI/AN-specific spiritual and cultural protective factors.

To fill this gap, the enhanced evaluation included two data analysis activities: (1) analysis of archival data from the Oregon Healthy Teens survey (OHT; statewide school survey based on the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System [45]) and (2) development and analysis of the Oregon Native Youth Survey (ONYS; survey of youth in Tribal communities in Oregon developed with a wide range of collaborators and implemented in Tribal communities). To develop the ONYS, the evaluation team attended quarterly meetings with Tribal prevention staff, social service managers, and state level prevention administrators. The team shared information during each step of the survey development process and asked these stakeholders for their feedback. This feedback included stakeholders' input on information deemed necessary, protective factors that should be included in the ONYS, and how to use the information once it was collected. It was extremely important for the survey to be culturally appropriate. Therefore, evaluation team members worked with a panel of experts gathered by NARA-NW as well as the Tribal stakeholders.

The Life is Sacred-enhanced evaluation yielded a number of important findings on factors that put AI/AN youth in Oregon at risk for suicide. The strongest risks for suicide attempts (for both Native and non-Native youth) were indicators of depression and generally poor emotional health. Other risk factors included being intentionally hit or physically hurt by an adult, having had sexual contact with an adult, and availability of drugs in the community. Native youth, on average, experienced two more risk factors than non-Native youth, although non-Native youth with seven or more risk factors were significantly more likely to attempt suicide, while for Native youth, the threshold was nine risk factors. Although Native youth experienced higher numbers of risk factors than non-Native youth, it was the number of risks that predicted suicide attempts, not race [46].

There were also a number of key findings from the Life is Sacred evaluation on factors that protect AI/AN youth from suicide. These factors included eating breakfast with family every day, making decisions with the family, good or excellent physical health, confidence in being able to work out problems, and getting good grades. In addition, data revealed a trend-level result that AI/AN youth's participation in cultural activities seems to buffer against risks for suicidality, and there was a positive association between youth valuing AI/AN traditional values/practices and protective factors in all five of the survey's domains (individual, peer, family, school, and community). Furthermore, protective factors buffered risk factors but had a more powerful effect for higher-risk youth (e.g., older youth) [46]. What follows is a description of the Life is Sacred actionable knowledge development process for making these enhanced evaluation findings accessible and usable for prevention action.

Step 1: what do we want our audience to do?

The most powerful protective factor that emerged from the ONYS data was family support [46]. This finding aligned well with the Tribes' interest in focusing their prevention efforts on protective factors and helped address a perceived common barrier, the lack of a supportive connection between parents/caregivers and teenagers. In addition, to sustain and expand upon current prevention efforts, Tribal staff needed support from their broader communities and their local leadership. More specifically, staff felt the need to connect the community and leadership with the issue of youth suicide and to help Tribal Councils feel connected to their Tribes' prevention efforts.

In addition to the quantitative findings from the ONYS, the evaluation staff also worked closely with the Tribal prevention staff and other stakeholders and culture experts to gather qualitative feedback on the evaluation and the potential application of its findings through actionable knowledge products. One of the key lessons learned from this qualitative work came from cultural experts. Discussing suicide was a complicated and difficult issue in most communities, and these experts provided suggestions on how, when, and where it was appropriate to talk about youth suicide directly and how to frame the issue within the context of health and healing, protection of young people from life's challenges, and building cultural identity and community support for youth.

Additional feedback was also sought throughout the development of the Life is Sacred actionable knowledge products to iteratively determine “what” should be included in the end products. Table 2 describes how the actionable knowledge goals were addressed during this process, the feedback received by Tribal staff, and the action that resulted from the process.

Table 2.

The Life Is Sacred actionable knowledge process

| Audience | Tribal input | Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Parents and caregivers | •There is need for a tool to educate, engage, and begin a conversation with parents/caregivers, reinforcing important prevention messages that the tribal staff are trying to share | •Brochure and companion talking points developed |

| •There is need for an accessible product for staff to display in their health clinics, counseling offices, and community centers as well as distribute when meeting with parents/caregivers and attending community events. | •Electronic version of brochure developed allowing customization with local contact information for users | |

| •Information in tools should be simple, aligned with prevention messaging used at the state level, and avoid “catch phrases” with inadvertent meanings | •Brochure disseminated in electronic and printed form to tribal prevention staff | |

| •Tools should include simple, positive, family-friendly language, images, and messages about the importance of parents/caregivers and simple steps they can take to make a difference in their children's lives | ||

| Tribal leaders | •Create a product illustrating the importance of focusing on youth suicide prevention, suicide risks and protective factors, and possible preventative steps that can be taken | •Electronic presentation template and companion talking points were developed |

| •Product should be useful for making presentations to Tribal Councils, county commissions, local funders, or community groups | •Presentation templates included standardized content plus placeholder slides for staff to add local information | |

| •Product should include a visual connection to native culture, but without negative associations such as spiders/spider webs, gangs (colors, symbols), drugs, or other unhealthy influences | •Slide templates include a yellow and red background with a feather image (native imagery), a forest scene (protection, strength, community), and a sunny landscape scene (life, hope, potential for growth, moving out of darkness) |

Step 2: who do we want to take action?

The Life is Sacred local evaluation included community assessments that allowed the evaluation team to learn about where each community was on its path to developing suicide prevention programs and infrastructure. For example, in some communities, the work was to increase the connections of parents/caregivers with their adolescent-aged children and educate them about the risks and protective factors associated with suicide. In other communities, there was a need to connect with both formal and informal Tribal leaders and raise awareness of the issue of youth suicide and the ways that the community could work to prevent it. Tribal prevention staff, through discussions at quarterly prevention meetings, decided that their most important audiences were: (1) Tribal leaders (particularly their Tribal Councils) and (2) parents/guardians/family members of the youth they work with or want to be working with [47].

Step 3: how should the message be packaged?

Using findings from the enhanced evaluation and lessons learned through the collaborative evaluation process, the evaluation team created two actionable knowledge products, a Family Brochure for parents/caregivers and an electronic presentation template intended for community members/Tribal leaders (http://www.sprc.org/library_resources/items/Life-is-Sacred-Native-Youth-Suicide-Prevention-materials). The Family Brochure provides information to start the conversation with parents and caregivers about how important their parenting role is, even (and especially) with their older children. The electronic presentation template helps Tribal prevention staff communicate to Tribal Councils and community members the importance of suicide prevention activities in their communities, including building protective factors such as connectedness to family, to community, and to culture. The presentation also allows a place for staff to include their own activities, successes, and challenges to individualize the content to their own communities. A set of talking points were also developed to accompany each of these products to provide additional guidance on the framing of actionable messages.

Step 4: with what effect?

The desired impacts of the Life Is Sacred actionable knowledge products were two-fold: (1) to educate parents and community members on the things that put AI/AN youth at risk for, or protect them from, suicide (indirect use) [28] and (2) to provide clear guidance on what parents and community members can do to prevent youth suicide in their communities (direct use) [28].

Also, preliminary findings on the dissemination and uptake of the Life is Sacred actionable knowledge products are encouraging. The Family Brochures have been enthusiastically used by several Tribal communities since they first became available. Several hundred copies of the final, Tribe-specific brochures were printed and delivered to the Tribes and Portland State University in 2011 in time for back-to-school activities. Although the Family Brochure is based upon Oregon data, actionable knowledge content from these brochures has been disseminated to other Northwest Tribal communities.

Evaluation of these actionable knowledge products and the strategies employed to disseminate and implement them will be important to determine their effectiveness in making evaluation findings actionable in Tribal communities. Some key evaluation questions include: are the actionable knowledge products being disseminated and implemented/used; if so, how? In which settings and contexts are they being disseminated and implemented/used the most/least? What are some of the barriers and/or facilitators to dissemination and implementation/use? Do the products increase awareness in the intended audiences? Do they lead to action/behavior change in the intended audiences? Do the actionable knowledge products resonate with other, unintended audiences (e.g., AI/AN parents and Tribal leaders outside of Oregon)?

Maine youth suicide prevention program

The Maine Youth Suicide Prevention Program (MYSPP) has focused on youth suicide prevention strategies since implementation of its state plan in 1998. Between 2002 and 2006, the University of Maine's Center for Research and Evaluation conducted an evaluation of MYSPP's Lifelines program in 12 Maine high schools. Lifelines is a comprehensive, school-based model of suicide prevention and postvention that prepares schools to identify and appropriately respond to youth at risk for suicide and, if a suicide occurs, manage the school environment to prevent further suicides. MYSPP evaluators and school leadership learned from the evaluation that schools could implement a comprehensive approach to youth suicide prevention and identify and refer students at risk for suicide, but technical support and training was needed to do so successfully [48]. This evaluation also showed that students who participated in courses that were a part of the Lifelines program had: (1) increased knowledge of suicide, (2) improved attitudes toward intervention, (3) a greater ability to recognize suicidal risk in a peer given a high ambiguity situation, and (4) a reduced willingness to keep a friend's suicidal thinking secret [49].

In 2005, the MYSPP was awarded a Garrett Lee Smith Memorial Act grant from SAMHSA to implement the Lifelines program in six additional high schools and add a community component. This community component, which included crisis agencies and community agencies, was added to create a network of schools and providers for each community. Because of this additional community component, researchers from the University of Maine and the University of Southern Maine were able to examine the identification and referral of youth at risk for suicide and suicidal behaviors among youth. Evaluation results indicated that schools that implemented the Lifelines program identified and responded to more youth at risk for suicide than schools that did not have the program [49]. They also revealed a number of barriers to collecting and using early identification and referral data. The process used to transform these evaluation findings into the MYSPP Early Identification and Referral Data Toolkit (http://www.sprc.org/library_resources/items/youth-suicide-prevention-referral-and-tracking-toolkit), an actionable knowledge tool for collecting and using early identification and referral data, is described next.

Step 1: what do we want our audience to do?

It is often difficult to identify students at risk for suicide due to inconsistent gathering of accurate early identification and referral data. This is due in large part to the fact that collecting accurate data to guide programming, in general, is often a challenge in applied settings, and this challenge is magnified when attempting to collect data in schools on sensitive topics, like risk for suicide. The enhanced evaluation of the Lifelines program revealed that when a school relies upon a gatekeeper surveillance system (e.g., relying on gatekeepers, such as teachers, to track and record youth at risk for suicide), data collection is difficult to coordinate and often not a natural component of this approach. As such, it became clear that data collection tools and processes that fit with a gatekeeper model of suicide prevention were needed to facilitate the collection of early identification and referral data for students at risk for suicide in schools.

A gatekeeper surveillance system relies on trained staff to recognize the signs of suicide risk and to respond by connecting the youth with services appropriate to the situation. Some of the key lessons learned about schools is that personnel in gatekeeper positions need additional supports to help them: (1) share information about students at risk, (2) capture data about the numbers or events that surround the identification and referral of a student, and (3) follow-up with students and/or their families to learn the results of the referral [49]. These actions make up the “what” of the MYSPP actionable knowledge product and are important because the information they help to gather facilitates a better understanding of students at risk and the events that lead to them being identified, and help to determine whether protocols and staff training are being applied to create a safety net for students in need of help. In addition, these data on the context of identification/referral and follow up are important because they are a potential source of evaluative information that can help with the continued refining of suicide prevention efforts.

Step 2: who do we want to take action?

The MYSPP-enhanced evaluation revealed that schools using a gatekeeper surveillance system to identify students at risk for suicide often encountered barriers to gathering accurate early identification and referral data. As such, the MYSPP Early Identification and Referral Data Toolkit is designed to help school personnel and evaluators that work with them collect data on youth who are identified as potentially at risk for suicide. More specifically, the toolkit is designed to support staff in schools that use gatekeepers to identify youth.

Step 3: how should the message be packaged?

In order to address the gap in the capacity of schools to collect important early identification and referral data, the MYSPP Early Identification and Referral Data Toolkit is an online resource that provides guidance and actionable tools for collecting these data in schools using a gatekeeper surveillance system. Each implementation of the Lifelines program has provided another opportunity to learn how to collect the best data possible from school staff, and these lessons learned have informed the development of the toolkit. Specifically, the toolkit shares the guidelines recommended by the MYSPP for schools to use in creating protocols that guide staff actions when they suspect a student may be at risk for suicide, become aware that a student has attempted suicide, or when a student dies by suicide. The toolkit also includes an improved, transferrable web-based data entry form that can be used by schools to track their school-based suicide prevention efforts, case studies of schools that have been successful in collecting data, and a checklist for facilitating good data collection.

Step 4: with what effect?

The desired impacts of the MYSPP toolkit are to help schools (1) capture data about students identified as potentially at risk for suicide and (2) use this data to continually evaluate and refine their suicide prevention efforts. Both of these intended outcomes reflect direct uses of actionable knowledge [28].

MYSPP staff and evaluators continually revise the web-based data entry form for schools based on feedback from those using it in practice. Some of the more formal evaluation questions that are yet to be examined include: does the checklist help with data collection? Does the collection form effectively capture data about the numbers or events that surround the identification and referral of a student? Does the toolkit facilitate sharing of information about students at risk? Does the toolkit facilitate follow-up with students and/or their families regarding results of referrals? Do schools use the data collected through the collection form to examine their suicide prevention work and/or refine suicide prevention efforts? Additional evaluation questions around the dissemination and implementation of the toolkit are similar to those for Tennessee's GTISS and include: which dissemination strategies appear to increase online “traffic” to the MYSPP toolkit? Have other organizations/websites “linked” to the toolkit? If so, what brought this about? Are additional implementation supports needed to successfully apply the MYSPP data template in local school settings? Is the need for these additional implementation supports dependent on existing school capacity/data systems? Do local attitudes around asking youth questions related to suicidal behavior impact implementation of the MYSPP toolkit? If so, how?

The knowledge–action gap is one of the most challenging barriers for public health practice [17], including suicide prevention. The TLC initiative, Life is Sacred Native Youth Suicide Prevention Program, and the Maine Youth Suicide Prevention Program used an adapted four-step actionable knowledge framework, informed by the best available evidence on knowledge translation, and created three very different actionable knowledge products to make their evaluation findings accessible, useful, and relevant for application in the field. Continued research and evaluation is needed to determine the extent to which this actionable knowledge framework and products successfully achieve these translation goals. It is hoped, however, that by providing processes for translating research and evaluation findings in a way that systematically considers the context and experiences of the audience, this adapted, theory-informed framework provides an opportunity for closing the gap between knowledge and action; therefore, improving suicide prevention practice and building opportunities for future research.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH AND EVALUATION

More research and evaluation are needed to test the benefits of actionable knowledge for applying evaluation findings to strengthen suicide prevention practice. For example, research could investigate whether and to what extent actionable knowledge products and accompanying dissemination and implementation strategies aid in the incorporation of knowledge into suicide prevention practice, particularly in comparison to other, more traditional knowledge creation and diffusion products (e.g., peer-reviewed articles, reports, nonaction-oriented translation documents, etc.). As research on effective suicide prevention strategies grows, studies could determine the extent to which actionable knowledge products aid in enhancing the uptake of evidence-based programs, practices, and policies, which dissemination and implementation strategies are most successful at completing the knowledge transfer of actionable knowledge into practice, whether actionable knowledge products enhance training efforts leading to better program implementation, and whether they strengthen data collection practices for data on suicidal behavior. In addition, research could examine which kinds of actionable knowledge products have the most powerful impact on bridging the knowledge–action gap in suicide prevention and in other public health issues. The impact of different kinds of actionable knowledge products may also differ depending on the type of knowledge (e.g., evaluation findings and effectiveness research findings), the contexts/settings in which this knowledge is being applied, and the kinds of dissemination and implementation strategies employed to support the integration of knowledge into practice. Studies also could examine whether the actionable knowledge process can be used by other government and tribal agencies, universities, and research institutions struggling to bridge the knowledge–action gap.

Answers to these questions can help clarify the role that actionable knowledge may play in applying research and evaluation findings to strengthen public health practice. Suicide prevention researchers can work toward answering these questions by integrating the development of actionable knowledge into their knowledge creation efforts and measuring the impact of actionable knowledge on the uptake of their research and evaluation findings in applied settings. This work will not only aid in bridging the knowledge–action gap but may also reveal the potential for creating actionable knowledge as standard practice in public health research.

CONCLUSION

The actionable knowledge tools and resources that were developed from the TLC-, Life is Sacred-, and the Maine Youth Suicide Prevention Program-enhanced program evaluations provide real world examples of the many ways research and evaluation can inform the practice of suicide prevention. By engaging gatekeepers throughout the training process, the evaluators and staff involved in the TLC-enhanced evaluation have developed a practical guide that assists organizations, trainers, and program managers in tailoring gatekeeper training experiences to specific settings/contexts and overcoming common barriers to implementation. The Life is Sacred-enhanced evaluation found that culture and family were essential protective factors for Tribal youth and developed resources for parents/caregivers, youth-serving professionals, and Tribal leaders that were packaged in ways the resonated most with the communities they were designed to serve. The Maine Youth Suicide Prevention Program's enhanced evaluation of the Lifelines program identified a communication gap between schools and community agencies that could be filled by making a data system template available for others.

These products offer the field of suicide prevention accessible and relevant information to improve practice. It is hoped that the framework for developing these actionable knowledge products, as described above, may inform future work in the translation of research and evaluation findings for action in public health practice. It is also hoped that the creation and packaging of actionable knowledge will strengthen suicide prevention practice, and by doing so, help to build the suicide prevention evidence base by increasing suicide prevention strategies' readiness for rigorous evaluation and research on effectiveness.

Acknowledgments

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Richard Puddy (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of Violence Prevention) and Dr. Richard McKeon (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) for their leadership and contributions to the Enhanced Evaluation Project. The authors would also like to recognize the contributions of Dr. Chad Rodi (ICF MACRO) and ICF MACRO in the Enhanced Evaluation Project and actionable knowledge tool development.

Footnotes

The Garrett Lee Smith Memorial Act (S.2175) provides federal funding for planning, implementation, and evaluation of organized activities involving statewide youth suicide early intervention and prevention strategies.

James Schut is now at the Graduate Psychology Program, Trevecca Nazarene University.

John Donovan is now at the National Center for Environmental Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Implications

Practitioners: The knowledge–action gap is one of the most challenging barriers for public health practice, including suicide prevention, and this actionable knowledge framework provides support for bridging this gap to improve prevention practice.

Researchers: This actionable knowledge framework can be used to strengthen suicide prevention practice and, by doing so, help to build the suicide prevention evidence base by increasing suicide prevention strategies' readiness for rigorous evaluation and research on effectiveness.

Policy makers: Making knowledge actionable is a key part of integrating research and lessons learned from evaluation into evidence-based policy development. This actionable knowledge framework can support and inform the policy-development process.

References

- 1.Crosby AE, Ortega L, Melanson C. Self-Directed Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements, Version 1.0. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). Available at: www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html. Accessed February 29, 2012.

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2011. Surveillance Summaries, June 8. MMWR 2012; 61 (No. 4). [PubMed]

- 4.U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Characteristics of public, private, and Bureau of Indian Education elementary and secondary teachers in the United States: Results from the 2007–08 Schools and Staffing Survey. NCES; 2009: 324.

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Suicide: definitions. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC. Available at: http://cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/suicide/definitions.html. Accessed on October 12, 2011.

- 6.Reducing Suicide: A National Imperative. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corso PS, Mercy JA, Simon TR, et al. Medical costs and productivity losses due to interpersonal violence and self-directed violence. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32:474–482. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dahlberg LL, Krug EG. Violence—a global public health problem. In: Krug E, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R, editors. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cavenaugh CE, Messing JT, Del-Colle M, O'Sullivan C, Campbell JC. Prevalence and correlates of suicidal behavior among adult female victims of intimate partner violence. Suicide Life Threat. 2011;24:372–383. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2011.00035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sansone RA, Gaither GA, Songer DA. The relationships among childhood abuse, borderline personality and self-harm behavior in psychiatric inpatients. Violence Vict. 2002;17:49–56. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.1.49.33636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiederman MW, Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Bodily self-harm and its relationship to childhood abuse among women in a primary care setting. Violence Against Wom. 1999;5:155–163. doi: 10.1177/107780129952004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Backer TE, David SL, Soucy G. Introduction. In: Backer TE, David SL, Soucy G, editors. Reviewing the Behavioral Science Knowledge Base on Technology Transfer. Rockville: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1995. pp. 147–168. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clancy CM, Cronin K. Evidence-based decision making: global evidence, local decisions. Health Affair. 2005;24:151–162. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrissey E, Wandersman A, Seybolt D, et al. Toward a framework for bridging the gap between science and practice in prevention: a focus on evaluator and practitioner perspectives. Eval. Program Plann. 1997;20:367–377. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7189(97)00016-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mann J, Apter A, Bertolote J, et al. Suicide prevention strategies: a systematic review. J. Amer. Med. Assoc. 2005;294:2064–2075. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.16.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.White J. Preventing Suicide in Youth: Taking Action with Imperfect Knowledge. Vancouver: University of British Columbia; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dearing JW. Applying diffusion of innovation theory to intervention development. Res Soc Work Pract. 2009;19:503–518. doi: 10.1177/1049731509335569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Graham I, Logan J, Harrison M, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J. Contin. Educ. Health. 2006;26:13–24. doi: 10.1002/chp.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles S. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1323–1327. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jack S, Tonmyr L. Knowledge transfer and exchange: disseminating Canadian child maltreatment surveillance findings to decision makers. Child Indic Res. 2008;1:51–64. doi: 10.1007/s12187-007-9001-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lavis J, Ross S, McCleod C, et al. Measuring the impact of health research. J. Health Serv. Res. Po. 2003;8:165–170. doi: 10.1258/135581903322029520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein K, Sorra J. The challenge of innovation implementation. Acad. Manage. Rev. 1996;21:1055–1080. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landry R, Amara N, Laamary M. Utilization of social science research knowledge in Canada. Res Policy. 1998;30:333–349. doi: 10.1016/S0048-7333(00)00081-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rimer BK, Glanz K, Rasband G. Searching for evidence about health education and health behavior interventions. Health Educ. Behav. 2001;28:231–248. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. 4. New York: Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lomas J. Using ‘Linkage and exchange’ to move research into policy at a Canadian foundation. Health Affair. 2000;19:236–240. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.3.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conklin A, Hallsworth M, Hatziandreu E, et al. Briefing on Linkage and Exchange: Facilitating Diffusion of Innovations in Health Services. Cambridge: Rand; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reardon R, Lavis J, Gibson J. From Research to Practice: A Knowledge Transfer and Planning Guide. Toronto: Institute for Work and Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blood MR. Only you can create actionable knowledge. Acad. Manag. Learn. Edu. 2006;5:209–212. doi: 10.5465/AMLE.2006.21253786. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schuchat, A, Bell, BP, Redd, SC. The science behind preparing and responding to pandemic influenza: the lessons and limits of science. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2011; Suppl 1: S8-S12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Reynolds B, Crouse-Quinn S. Effective communication during an influenza pandemic: the value of using a crisis and emergency communication framework. Heal Promot Pract. 2008;9:13S–17S. doi: 10.1177/1524839908325267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nielsen-Bohlman L. Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tenkasi R, Hay G. Actionable knowledge and scholar-practitioners: a process of theory–practice linkages. Syst. Pract. Act. Res. 2004;17:177–206. doi: 10.1023/B:SPAA.0000031697.76777.ac. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lavis JN, Robertson D, Woodside JM, McLeod CB, Abelson J. How can research organizations more effectively transfer research knowledge to decision makers. Millbank Q. 2003;81:221–248. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.t01-1-00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Puddy, R, Wilkins, NJ, Thigpen, S, et al. Expanding the definition for evidence in child maltreatment prevention. In: Alexander, S, Alexander, R, Guterman, N, eds. Prevention of Child Maltreatment. St. Louis, MO: G.W. Medical Publishing; in press.

- 36.Puddy R, Wilkins N. Understanding Evidence Part 1: Best Available Research Evidence. A Guide to the Continuum of Evidence of Effectiveness. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thigpen, S, Puddy, R, Singer, H. Building the bridge: developing the Rapid Synthesis and Translation Process (RSTP) within the Interactive Systems Framework (ISF). J. Community Psychol. Special Issue;in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Chagnon F, Houle J, Marcous I, et al. Control-group study of an intervention training program for youth suicide prevention. Suicide Life-Threat. 2007;37:135–144. doi: 10.1521/suli.2007.37.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keller D, Schut J, Puddy R, et al. Tennessee Lives Count: statewide gatekeeper training for youth suicide prevention. Prof Psychol. 2009;40:126–133. doi: 10.1037/a0014889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.King K, Smith J, Project SOAR A training program to increase school counselors' knowledge and confidence regarding suicide prevention and intervention. J. School Health. 2000;70:402–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2000.tb07227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matthieu MM, Cross W, Batres AR, et al. Evaluation of gatekeeper training for suicide prevention in veterans. Arch. Suicide Res. 2008;12:148–154. doi: 10.1080/13811110701857491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wyman PA, Brown CH, Inman J, et al. Randomized trial of a gatekeeper program for suicide prevention: 1-year impact on secondary school staff. J. Consult. Clin. Psych. 2008;76:104–115. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schut, LJ, Luellen, J, Lockman, JD, et al. Psychometric analysis of measures in evaluation of gatekeeper training for suicide prevention. Manuscript in preparation.

- 44.Lockman, JD, Padgett, JH, Williams, L, et al. Creating the shield of care gatekeeper training for staff in juvenile justice systems: using evaluation data for program improvement. Manuscript in preparation.

- 45.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth risk behavior surveillance system. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/index.htm. Accessed on January 10, 2012.

- 46.Mackin, JR, Perkins, T, Tarte, J, et al. Life is Sacred Program enhanced evaluation: Oregon Native Youth Survey data multi-tribal community report. Prepared for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2011; Unpublished report.

- 47.Quarterly Tribal Prevention Meeting, March 9, 2010, Celilo, Oregon.

- 48.Madden, M, & Lichter, E. Maine youth suicide prevention program enhanced evaluation report. Prepared for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.2010; Unpublished report.

- 49.Madden, M, Haley, D, Hart, S, et al. An evaluation of Maine's comprehensive school-based youth suicide prevention program.Orno, ME: Center for Research and Evaluation, University of Maine. 2011. Unpublished report. Available at: http://www.maine.gov/suicide/docs/Final_CDCEvalPublicReport3-09.pdf. Accessed on January 10, 2011.