Abstract

Background

Primary care physicians are expected to coordinate care for their patients.

Objective

Assess the number of physician peers providing care to the Medicare patients of a primary care physician

Design

Cross-sectional analysis of claims data

Setting

Fee-for-service Medicare in 2005

Participants

2,284 primary care physicians who responded to the 2004-2005 Community Tracking S (CTS) Physician Survey.

Measurements

Primary patients for each physician identified as beneficiaries for whom the physician billed for more evaluation and management visits than any other physician in 2005. The number of physician peers for each physician was the sum of 1) other unique physicians that the index physician's primary patients visited, and 2) other unique physicians who served as the primary physician for each of the index physician's non-primary patients during 2005.

Results

The typical primary care physician has 229 (IQR125-340) other physicians working in 117 (IQR66-175) different practices with whom care would have to be coordinated, equivalent to an additional 99 physicians and 53 practices for every 100 Medicare beneficiaries managed by the primary care physician. Considering only the 31% of a primary care physician's primary patients who had 4 or more chronic conditions, the number of peers was still substantial [86 physicians in 36 practices]. The number of peers varied with geographic region, practice type, and reliance on Medicaid revenues.

Limitations

Estimates are based on only fee-for-service Medicare patients and physician peers, and therefore likely undercount the number of peers. The modest response rate of the CTS survey may bias results in unpredictable directions.

Conclusion

In caring for his or her own primary and non-primary patients over one year, each primary care physician potentially must coordinate with a large number of individual physician colleagues who also provide care to these patients.

Keywords: organization of care delivery, care coordination, Medicare

Introduction

Coordination of care involves the integration of care across all of a patient's conditions and needs, across providers and settings, and in accordance with the preferences and capabilities of patients and their families (1,2,3). Coordination comprises complex activities that require conscious interactions between different providers and between providers and patients, including timely transfer of accurate clinical information, effective communication between the involved parties, and shared decision-making.

Primary care physician societies advocate support for the Advanced Medical Home, conceived as a physician-directed practice that provides coordinated, accessible, continuous, and comprehensive care (4). Public and private sector payers have been responsive, recognizing that better coordination is critical to achieving high quality and efficient health care, particularly for patients with chronic or complex healthcare needs (5,6). Payers are considering providing direct financial incentives to physicians for delivery of “medical home” services and bonuses based on standardized measures of patient experience that reflect coordination-related performance (7,8,9). However, such strategies may not succeed if they do not realistically assess the magnitude of care coordination tasks within the current system.

One important dimension of the burden of care coordination relates to how fragmented care for a given patient may be across different care settings and providers (1,2,3). Greater fragmentation increases the challenge to effective coordination. Care in fee-for-service Medicare, where effective coordination could greatly improve outcomes, is currently quite fragmented. Beneficiaries typically see seven different physicians from four different practices in a given year, and those with multiple chronic illnesses have even more fragmented care (10). Because the cadre of physicians seen may vary for each patient, a physician trying to coordinate care for many Medicare patients would need to communicate regularly and effectively with large numbers of other physicians with whom he or she shares responsibility for at least some patients. In order to inform the design of policies to foster and support coordination, we estimated the number of peers for the typical primary care physician, based on annual visits of their Medicare patients to other physician practices.

Methods

Medicare claims and Community Tracking Study Physician Survey linked data

We analyzed fee-for-service claims for a single year (2005) for beneficiaries treated by primary care physician respondents to the nationally representative 2004-2005 Community Tracking Study (CTS) Physician Survey (11,12). The CTS survey relied upon a sample from the American Medical Association's Masterfile that was clustered in 60 metropolitan statistical areas. In 2004-2005, the survey had a response rate of 53%, comparable to that for most physician surveys (13). The survey excludes physicians providing less than 20 hours of direct patient care per week, as well as specialists such as anesthesiologists, radiologists, and pathologists. We further excluded from analysis all claims submitted by CTS and non-CTS specialists in these categories or by pediatricians. We included all beneficiaries aged 65 or older as of January 1, 2005 that qualified for Medicare on the basis of age.

Identifying Physicians, Practices, and Peers

We used the “performing physician” Unique Physician Identification Number coded on claims to identify individual physicians billing for specific services, and the corresponding Tax Identification Number representing the organization that Medicare reimburses, to identify practices. We found agreement between physicians' self-reported practice size from the CTS survey, and the number of Unique Physician Identification Numbers associated with his/her Tax Identification Number, in 78% of cases (Appendix A). Where there was disagreement, practice size based on Tax Identification Numbers was larger than self-reported practice size in the vast majority (80%) of cases, suggesting that use of Tax Identification Numbers would have the conservative effect of reducing counts of peers. We used the Health Care Financing and Administration (HCFA) specialty codes for each UPIN to identify the physician's specialty using an algorithm developed in prior work and which were verified against the self-reported specialties of CTS physicians (10).

We conceive of each primary care physician as having varying levels of responsibility for coordinating care – more responsibility as the main coordinator for patients for whom they serve as the primary physician, and lesser responsibility as a participant in the management of care for all their other patients, who have a different physician as their primary physician.

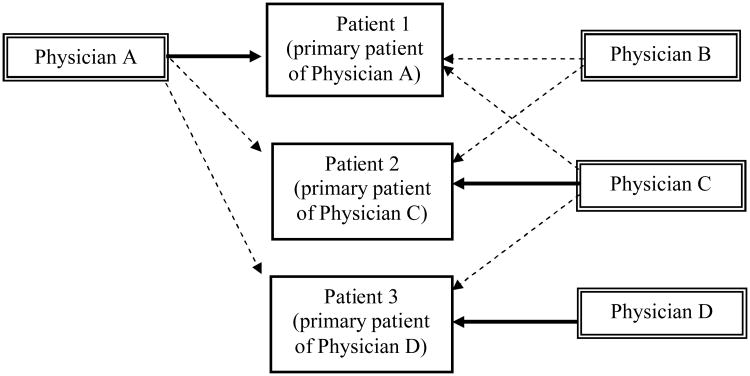

We therefore estimated the number of peers for a CTS primary care physician as the sum of: 1) all other physicians or practices that treated the beneficiaries for that physician's core patients, based on the CTS primary care physician having billed for the greatest number of evaluation and management visits (hereafter “primary patients” or “primary providers”) (14); plus 2) the other physicians or practices that served as the primary provider (coordinator) for each of the CTS primary care physician other, non-primary patients – that is, one additional peer for each of the CTS primary care physician's non-primary patients. Figure 1. In the case of two or more physicians being “tied” by virtue of having billed the same number of visits (fewer than 10% of patients) we selected: 1) primary care physicians over specialists, then 2) the physician who billed for the greatest total number of relative value units. For any remaining ties, we randomly assigned patients to one of the tied physicians. For the minority of patients who did not have any evaluation and management visits, we identified the physician who billed for the greatest number of their total visits. While our main analyses focus on each “practice” (Tax Identification Number) as a unique peer, we also calculated the number of peers counting each physician (Unique Physician Identification Number) as a unique peer. To assess the robustness of our results to different methods of assignment, we repeated analyses holding physicians responsible for patients for whom they billed for at least half of evaluation and management visits (Majority assignment) (10).

Figure 1. Calculating the Number of Physician Peers.

Solid arrows represent a physician being linked to his or her “medical home” patients based on having billed for the plurality of that patient's evaluation and management visits, while dashed arrows represent linkages to a physician's other, “non-medical home” patients. In this example, we calculated the number of peers for Physician A by counting Physicians B, C, and D each only once, and did not include Physician A in that count, resulting in a total of three peers.

While we considered only physician-related evaluation and management visits when identifying primary patients or primary providers, we considered all physician-related visits (including procedures), except those billed by the excluded specialists listed above, in our main calculations of the number of peers. This is consistent with our conceptual framework, which posits that physicians are responsible for coordinating all types of care that their patients receive from other physicians, not only care delivered in evaluation and management encounters. In secondary analyses, we repeated calculations focusing only on peers who provided physician-related evaluation and management visits.

We also characterize the number of peers by standardizing to the number of Medicare beneficiaries in each CTS primary care physician's patient panel. To demonstrate the relative contributions of different types of care situations, we calculated the number of peers considering visits only for patients with four or more chronic conditions, and visits to: 1) all physician peers; 2) physician peers not in emergency departments; 3) physician peers providing evaluation and management services; 4) physician peers practicing in the CTS primary care physician's state; and 5) peers comprised of other primary care physicians, medical specialists, and surgeons.

We assessed variation in the number of peers across characteristics of the CTS primary care physician and his or her practice, including: the number of Medicare patients; the mean number of chronic conditions for those patients; urban vs. rural location; geographic region; the supply of medical specialists in the metropolitan area; the physician's practice type and size, and percentage of practice revenue derived from Medicaid.

Statistical analyses

For each outcome metric, we calculate medians and inter-quartile ranges. We examined the number of peers relative to characteristics of the individual CTS primary care physicians (number of years in practice and percentage of revenue derived from Medicaid), their practices, and their fee-for-service Medicare patient panels. Practice characteristics included: type and size; urban/rural location; geographic region; and the number of physician practices and specialists per 1,000 capita in the metropolitan statistical area, respectively, using data from the 2000 Area Resources File. Characteristics of patient panels included the number of beneficiaries treated in year 2000, and their mean number of chronic conditions (15,16).

In generating national estimates, we weighted data to account for the survey sampling strategy and non-response (11). Weighted percentages are representative of all non-Federal primary care physicians in the U.S. who provide direct patient care at least 20 hours a week. Analyses were conducted using SAS, release 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary NC) and SUDAAN analytic software (release 7.0, Research Triangle Institute International, Research Triangle Park, NC) software. This study was approved by the institutional review contractor for Mathematica, Inc. (Washington, DC), the parent corporation of the Center for Studying Health System Change.

Results

576,875 Medicare beneficiaries had at least one visit with one of 2,284 CTS primary care physicians in the year 2005. Each physician treated an average of 264 unique beneficiaries, including 113 (38%) “core” (primary) patients and 151 other (non-primary) patients. The typical CTS primary care physician had peers consisting of 117 distinct practices and 229 unique physicians. (Table 1) This included a median of 64 (Inter-quartile range 35-95) other primary care physicians, 77 (40-118) medical specialists, and 65 (30-104) surgeons. For every 100 beneficiaries that a CTS primary care physician treated in year 2005, he or she typically had 99 physicians and 53 practices communicate with in order to coordinate care. We detail the number of peers associated with care of primary patients versus non-primary patients in Appendix B.

Table 1. Number of Other Physicians and Practices Among Whom Primary Care Physicians Must Coordinate Care for Fee-for-Service Medicare Beneficiaries, under Different Methods of Assigning Patients to Physicians.

| Plurality Assignment | Majority Assignment | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Peers per 100 Medicare Beneficiaries | Total Number of Peers | Number of Peers per 100 Medicare Beneficiaries | Total Number of Peers | |||||

|

|

||||||||

| Median | IQR | Median | IQRb | Median | IQR | Median | IQRb | |

|

|

||||||||

| Number of other practices | ||||||||

| Related to care of all Medicare patients | 53 | 35-84 | 117 | 66-175 | 27 | 14-45 | 67 | 28-104 |

| Related only to care of primary patients with 4 or more chronic conditionsc | 36 | 18-62 | 86 | 41-138 | 24 | 13-40 | 61 | 28-95 |

| Related to care provided during one monthd | 7 | 4-11 | 18 | 8-29 | 4 | 2-7 | 10 | 4-19 |

| Total number of other physicians | 99 | 70-143 | 229 | 125-340 | 33 | 22-52 | 78 | 41-118 |

| Number of other primary care physicians | 29 | 20-41 | 64 | 35-95 | 17 | 12-44 | 40 | 20-60 |

| Number of medical specialists | 32 | 20-52 | 77 | 40-118 | 19 | 11-30 | 47 | 22-74 |

| Number of surgeons | 28 | 17-44 | 65 | 30-104 | 17 | 10-28 | 41 | 17-69 |

| Number of emergency medicine physicians | 7 | 3-11 | 17 | 7-27 | 4 | 1-8 | 11 | 3-19 |

|

|

||||||||

Based on Medicare claims data for 576,875 fee-for-service beneficiaries treated at least once by one of 2,284 Community Tracking Study primary care physicians in the year 2005. Peer network size was calculated as the sum of 1) the number of other practices where physicians also treated the primary patients of the CTS primary care physician; plus 2) the practice of the physician that served as the primary provider for the CTS primary care physician's other (non-primary) Medicare patients. Primary patients were identified as beneficiaries for whom the CTS primary care physician billed the greatest number of evaluation and management visits (Plurality assignment) or with the added criterion that the CTS primary care physician billed for at least 50% of evaluation and management visits (Majority assignment) in year 2005. Ties were resolved by assignment to the physician who billed for the greatest total charges for that beneficiary. Primary patients accounted for a median of 50% and 30% of a CTS primary care physician's Medicare panel under Plurality and Majority assignment, respectively.

Denotes inter-quartile range.

The number of chronic conditions was determined using the method of Hwang et al. These patients accounted for a median of 31 percent of each CTS primary care physician's Medicare panel.

Monthly medians were calculated based on visits in March, June, and September 2005. IQR denotes inter-quartile range.

Over the course of one month, the typical number of peers included 18 practices. The absolute and standardized numbers of peers were lower when we assigned patients to physicians based on “majority assignment” [total of 78 practices and 146 physicians], equivalent to 61 physicians and 33 practices per 100 Medicare beneficiaries. However, under this assignment approach, only 30% (median of 80 patients) of each physician's panel was considered their primary patients.

The number of peers was still substantial when we considered only important subsets of services. A median of 70 (35-109) practices were involved in providing evaluation and management visits for a primary care physician's patients, equivalent to 32 practices per 100 beneficiaries. Peers providing outpatient visits, visits outside of an emergency room, and visits within the primary care physician's state included a median of 99 (45 per 100 beneficiaries), 110 (51 per 100 beneficiaries), and 95 (45 per 100 beneficiaries) practices, respectively.

Variation in the number of peers by physician, practice, patient panel, and area characteristics

Standardized to the size of the CTS primary care physician's Medicare panel, the number of peers did not vary with the number of years the physician had been in practice, but was inversely related to the percentage of revenue that was derived from Medicaid. Physicians working in solo/2-person practices had more peers [median 68 practices per 100 beneficiaries] than those in larger group practices and institutional work settings. (Table 2)

Table 2. Number of Other Practices Among Whom Primary care physicians Have to Coordinate Care for Fee-for-Service Medicare Beneficiaries, by the Characteristics of the Physicians, Their Practices, and Their Patient Panels.

| Plurality Assignment | Majority Assignment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician and Practice Characteristics | N (%) Total = 2,284 | Number of Peers per 100 Medicare Beneficiaries, Median (IQR) | Total Number of Peers, Median (IQR) | Number of Peers per 100 Medicare Beneficiaries, Median (IQR) | Total Number of Peers, Median (IQR) |

|

|

|||||

| Years in practice | |||||

| <5 | 366 (15.4) | 53 (35-72) | 90 (48-144) | 29 (20-40) | 50 (26-85) |

| 5-9 | 451 (18.3) | 51 (35-84) | 106 (61-188) | 31 (22-51) | 71 (34-124) |

| >9 | 1,467 (66.3) | 55 (35-87)c | 128 (75-180)c | 35 (22-54)c | 86 (46-121)c |

| Practice type | |||||

| Solo/2-person | 885 (39.6) | 68 (45-102) | 136 (83-199) | 44 (31-67) | 92 (55-137) |

| Small group, 3-10 | 325 (15.0) | 45 (32-71)c | 155 (93-200)a | 28 (20-46)c | 72 (56-131)a |

| Medium group, 11-50 | 164 (6.8) | 43 (36-62)c | 136 (74-173) | 29 (20-45)c | 86 (47-110) |

| Large group, >50 | 96 (4.8) | 45 (28-74)c | 136 (67-178) | 28 (16-36)c | 81 (39-125) |

| Medical school | 130 (4.5) | 57 (45-80)c | 71 (36-121)c | 31 (21-44)c | 40 (17-69)c |

| Hospital office/Other | 592 (25.2) | 43 (28-69)c | 90 (50-143)c | 28 (17-40)c | 55 (29-92)c |

| Group/staff health maintenance organization | 92 (4.1) | 46 (25-94) | 43 (4-61)c | 27 (14-49) | 24 (4-41)c |

| Percent of revenue derived from Medicaid | |||||

| 0-5% | 972 (38.9) | 64 (41-100) | 135 (77-203) | 39 (24-59) | 87 (43-132) |

| 6-15% | 618 (30.4) | 49 (35-75)c | 127 (81-176) | 31 (21-48)c | 86 (52-119)c |

| >15% | 694 (30.8) | 46 (33-70)c | 88 (49-142) | 31 (21-44)c | 57 (30-93)c |

| Urban | 1,985 (80.6) | 60 (40-92) | 118 (64-181) | 36 (24-55) | 77 (38-120) |

| Rural | 299 (19.4) | 36 (26-47)c | 108 (72-157) | 26 (18-35)c | 82 (50-109) |

| Census division | |||||

| New England | 190 (7.8) | 50 (32-75) | 98 (56-129) | 30 (19-46) | 57 (30-88) |

| Mid-Atlantic | 319 (12.0) | 81 (58-104)b | 148 (82-211)c | 42 (34-69)c | 94 (49-140)c |

| East North Central | 409 (17.9) | 50 (34-70) | 117 (77-161)c | 31 (21-45) | 79 (44-115)c |

| West North Central | 82 (3.0) | 46 (31-65) | 78 (47-115) | 28 (19-38) | 39 (27-71) |

| South Atlantic | 482 (20.9) | 51 (33-83) | 145 (92-193)c | 31 (20-50) | 95 (55-128)c |

| East South Central | 82 (5.8) | 37 (28-51) | 142 (92-197)c | 27 (20-35) | 101 (75-131)c |

| West South Central | 240 (10.4) | 47 (33-78) | 114 (65-186)c | 32 (21-45) | 77 (43-138)c |

| Mountain | 156 (6.6) | 62 (31-100) | 104 (53-205) | 35 (21-60) | 66 (32-127) |

| Pacific | 324 (15.6) | 56 (38-86) | 76 (33-124) | 36 (25-55) | 50 (19-89) |

| Number of specialist physicians per 1,000 capita | |||||

| Lowest quintile | 393 (20.2) | 37 (29-59) | 108 (72-156) | 28 (20-39) | 79 (48-115) |

| Fourth quintile | 423 (19.9) | 52 (33-84)c | 101 (60-166) | 31 (19-48) | 63 (34-104) |

| Third quintile | 465 (19.8) | 65 (42-97)c | 99 (44-167) | 38 (25-64) | 64 (27-105) |

| Second quintile | 428 (18.2) | 53 (36-79)c | 138 (76-191)a | 33 (20-49) | 86 (42-124) |

| Highest quintile | 575 (21.9) | 62 (42-94)b | 143 (83-202)c | 41 (26-57)c | 91 (49-129)c |

| Patient Panel Characteristics | |||||

| Number of Medicare beneficiaries | |||||

| 1-100 | 623 (24.4) | 88 (57-130) | 34 (12-67) | 51 (33-80) | 21 (6-40) |

| 101-200 | 523 (21.7) | 69 (48-94)c | 101 (71-137)c | 43 (31-60) | 65 (43-92)c |

| 201-400 | 665 (29.3) | 49 (36-62)c | 141 (101-175)c | 32 (23-44)c | 89 (65-121)c |

| >400 | 473 (24.6) | 32 (22-44)c | 193 (151-262)c | 20 (15-28)c | 129 (96-167)c |

| Mean number of chronic conditions | |||||

| Lowest quartile | 576 (24.4) | 53 (34-82) | 83 (43-139) | 36 (25-52) | 59 (28-94) |

| Third quartile | 597 (25.6) | 46 (33-75)c | 118 (73-173) | 30 (20-48) | 81 (44-114) |

| Second quartile | 500 (24.7) | 57 (36-84)c | 141 (78-194) | 34 (20-51) | 86 (44-139)b |

| Highest quartile | 611 (25.3) | 62 (38-96)c | 134 (70-199)b | 33 (23-57) | 81 (41-125) |

|

|

|||||

Based on Medicare claims data for 576,875 fee-for-service beneficiaries treated at least once by one of 2,284 Community Tracking Study primary care physicians in the year 2005. Peer network size was calculated as the sum of 1) the number of other practices where physicians also treated the primary patients of the CTS primary care physician; plus 2) the practice of the physician that served as the primary provider for the CTS primary care physician's other (non-primary) Medicare patients. Primary patients were identified as beneficiaries for whom the CTS primary care physician billed the greatest number of evaluation and management visits (Plurality assignment) or with the added criterion that the CTS primary care physician billed for at least 50% of evaluation and management visits (Majority assignment) in year 2005. Ties were resolved by assignment to the physician who billed for the greatest total charges for that beneficiary. Primary patients accounted for a median of 50% and 30% of a CTS primary care physician's Medicare panel under Plurality and Majority assignment, respectively. IQR denotes inter-quartile range.

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

p<0.001 for comparisons to the first category for each variable.

The median number of practices among peers per 100 beneficiaries was higher in urban [median 60 (40-92)] than in rural areas [median 36 (26-47)]. Number of peers also varied considerably across Census regions, from a median of 37 practices per 100 beneficiaries in the East South Central region (Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee) of the United States to 81 practices in the Mid-Atlantic region (New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania) (17). The standardized number of peers steadily increased with the supply of specialist physicians in the metropolitan area where the CTS primary care physician practiced.

Physicians who treated patients with more chronic conditions had more peers than those whose patients were healthier – from a median of 53 practices per 100 beneficiaries for primary care physicians whose Medicare patients were in the lowest quartile in terms of chronic illness burden, to 62 practices for those whose patients were in the highest quartile. Although the absolute number of peers grew with the number of beneficiaries a CTS primary care physician treated, physicians with larger Medicare patient panels actually had fewer peers per 100 beneficiaries (Table 2).

Discussion

Care coordination may improve health outcomes and reduce costs, especially for patients with multiple chronic conditions (1). But coordination may be particularly challenging in the fee-for-service Medicare program, which lacks defined provider networks, providers designated to guide referrals, systems to track referrals, and explicit incentives to coordinate care. Given the efforts required for effective communication and shared decision-making between just two providers caring for a single patient, care coordination writ large across all patients and all peers for a given primary care physician may be formidable in a fee-for-service context.

In order to assess the burden on a physician charged with coordinating care, we estimated the number of peers for a large, representative sample of primary care physicians. We found that in a single year for just their fee-for-service Medicare patients, the typical primary care physician needs to coordinate care with 229 other physicians working in 117 different practices. The number of peers was substantial even when we restricted estimates to only include peers billing for outpatient or evaluation and management encounters, or those caring for the primary care physician's “core” patients. And the number of peers was greater for physicians treating patients with higher chronic illness burden, who may benefit the most from coordination.

These physician-level results are consistent with studies that measured other aspects of fragmentation in the care delivery system from the perspective of patients and communities, but to our knowledge are unique in their national representativeness and consideration of a broad range of specialist peers (10,18,19,20). Fragmentation in Medicare likely reflects the freedom of beneficiaries to seek care from any participating provider without prior approval, the incentives that fee-for-service payment creates for providers to provide more services, the lack of disincentives for providers to limit referrals, and the greater care needs of an elderly population.

Our findings should be interpreted within the context of our analytic approach. We did not assess associations between the number of peers and cost or quality of care. Neither did we assess the longitudinal stability of links between peers; familiarity may facilitate more effective coordination strategies over time. And fee-for-service claims do not allow us to gauge the appropriateness or directionality of referrals. We used Unique Physician Identification Numbers and Tax Identification Numbers, both of which have limitations as ways of discriminating individual physicians and practice organizations. Affiliated physicians sometimes bill under a common Unique Physician Identification Number, and a minority of physicians (<15%) are affiliated with more than one organizational Tax Identification Number. However, even this minority group used a single number to bill for more than 85% of their Medicare encounters (data not shown). We focused primary analyses on Tax Identification Numbers, which Medicare uses to direct reimbursement, because they are more reliable and result in more conservative estimates. Finally, the modest response rate of the CTS survey may bias our findings in unpredictable directions, although we used a stringent method to calculate response rates, weighted analyses for non-response, and rely on prior studies demonstrating that estimates of survey responses remain stable at this response rate compared to a response rate of 65 percent.

Our findings represent conservative estimates of the number of peers for several other reasons. We did not consider non-physician providers such as nurse practitioners, or peers exclusively involved in the care of the primary care physician's non-Medicare or Medicare managed care patients. We used the plurality method to assign patients to their “primary physician,” an approach that typically results in assignment of less than 40% of a primary care physician's Medicare panel as his or her primary patients. Other approaches to assignment, such as shared assignment of patients between providers, that increase the number of assigned patients to a particular physician would concomitantly inflate the count of peers. The exclusion of physicians such as radiologists, pathologists, and anesthesiologists presupposes that no interaction is required between a primary care physician and these physicians less involved in longitudinal care, while realistically some coordination is needed.

Even restricting analyses to only on evaluation and management visits resulted in substantial counts of peers. We included physicians in eligible specialties providing other services and interventions because a core element of care coordination is the arrangement and management of the care that a patient's receives from these categories of physicians.

We assessed the number of peers, but not efforts related to other important activities, such as the frequency, mode, or quality of communication with patients' families or of interactions between providers. Neither did we examine other obstacles to coordination in a program of national scope. For example, only a few communities have the infrastructure to enable electronic exchange of clinical data, and even these may not capture all peers, which often include those in different states (21).

Even within this focused analysis, the logistical challenges to care coordination appear daunting. Payers could approach these challenges by recognizing coordination in complex fee-for-service systems as a multi-directional activity, centered on the primary physician, but involving specialists and also other primary care physicians. Few population-based data are available on the sources of care encounters (the degree to which they are initiated by referrals by the primary physician, from another physician, or patient self-referral). Policies that extend incentives to other providers to encourage communication and shared decision-making with the primary physician may be more effective than those targeting only one central physician (2). Further investigation into the longitudinal stability of linkages between peers, the degree to which the care coordination efforts of physicians vary across different types of peers, and the impact of interventions such as payment for “medical home” services on the number of peers would offer valuable insights to support policies to improve coordination.

Payers like Medicare could design systems to track the sources of referrals by tying payment to the designation of a referring provider (perhaps within claims). Payers could also seek to identify “peer webs,” with the goal of providing bundled payments to groups of physicians working in concert to care for a patient. Peer webs could be identified retrospectively in a manner similar to our analyses. Or, groups of physicians can prospectively form webs by identifying one another as peers. Under either scenario, physicians who already work in, or are willing to move into, large multispecialty practices focused on integrating care delivery would have an advantage (22).

Our sample did not include enough physicians working in very large practices (i.e., those over 200) to examine whether they have even fewer peers. Other physicians who work in small or single-specialty practices already cultivate informal webs of trusted colleagues to whom they can turn, either in the role of referring or consulting physician, for clinical advice. Formalizing similar relationships with other providers could increase integration while allowing physicians to choose peers without forming large practices.

Explicit payment for medical home services could encourage physicians to select peers in such a fashion. For instance, physicians could scale up innovative models, such as “service agreements” that guide referrals between different practices, to broadly improve coordination (23). In either type of arrangement, physicians could make the adoption of compatible electronic medical records a criterion for selection as a peer. To rationally apply other standards in selecting peers, physicians would need accurate data on their cost and quality performance. Without such facilitating changes in the organization of care delivery, care coordination is likely to remain an ideal but elusive goal in Medicare.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: This study was supported by grant R01 AG025687-01A1 from the National Institute on Aging, and by the American Medical Group Association. The funders had no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of the study. None of the authors had any potential conflicts of interest relevant to the subjects in the study. Dr. Pham had full access to all of the data in the study, and takes responsibility for their integrity and the accuracy of the analysis.

Appendix A.

Agreement between CTS primary care physicians' self-reported practice size vs. the number of Unique Physician Identification Numbers associated with the physician's Tax Identification Number in Medicare claims.

| Practice size based on claims | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 or 2 n (%) |

3-10 n (%) |

11-50 n (%) |

51 or more n (%) |

N = 1,480 (%) | |

|

|

|||||

| Self-reported practice size, n (%) | |||||

| 1 or 2 | 720 (93.3) | 126 (32.7) | 35 (16.3) | 9 (5.9) | 890 (59.8) |

| 3 or 10 | 46 (6.3) | 221 (65.3) | 40 (16.1) | 20 (15.3) | 327 (22.6) |

| 11 to 50 | 3 (0.3) | 9 (1.7) | 135 (62.1) | 20 (11.4) | 167 (10.4) |

| 51 or more | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.3) | 11 (5.5) | 83 (67.4) | 96 (7.2) |

| Total (% of whole) | 770 (52.0) | 357 (24.1) | 221 (14.9) | 132 (8.9) | |

Based on Medicare claims data for fee-for-service beneficiaries treated at least once by one of 1,480 Community Tracking Study primary care physicians in the year 2005. Excludes CTS physicians who reported working in practice types other than solo and group practices (e.g., hospital-based practice, medical school, group/staff HMO), because these physicians were not asked on the survey to report practice size. The darkest cells on the diagonal indicate agreement (1,159 total, or 78% of 1,480 primary care physicians). Cells shaded in light gray signify physicians for whom practice size based on the number of Unique Physician Identification Numbers associated with their Tax Identification Number was larger than their self-reported practice size (250 total, or 16.9% of 1,480 primary care physicians).

Appendix B.1.

Number of Other Physicians and Practices Among Whom Primary Care Physicians Must Coordinate Care for Fee-for-Service Medicare Beneficiaries Who Are Their Primary- and Non-primary Patients.

| Care of Primary Patients | Care of Non-Primary Patients | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Peers per 100 Medicare Beneficiaries | Total Number of Peers | Number of Peers per 100 Medicare Beneficiaries | Total Number of Peers | |||||

|

|

||||||||

| Median | IQR | Median | IQRb | Median | IQR | Median | IQRb | |

|

|

||||||||

| Number of other practices | ||||||||

| Related to care of all Medicare patients | 39 | 20-68 | 91 | 39-146 | 18 | 12-28 | 39 | 20-64 |

| Related only to care of primary patients with 4 or more chronic conditionsc | 36 | 18-62 | 86 | 41-138 | 15 | 10-24 | 33 | 17-58 |

| Related to care provided during one monthd | 6 | 3-10 | 15 | 5-27 | 2 | 1-3 | 4 | 2-7 |

| Total number of other physicians | 80 | 44-127 | 187 | 85-297 | 26 | 19-40 | 57 | 29-99 |

| Number of other primary care physicians | 17 | 10-26 | 42 | 19-65 | 12 | 7-20 | 24 | 12-46 |

| Number of medical specialists | 28 | 14-46 | 68 | 29-108 | 8 | 5-12 | 18 | 8-30 |

| Number of surgeons | 26 | 13-42 | 61 | 22-99 | 6 | 4-8 | 13 | 6-22 |

| Number of emergency medicine physicians | 7 | 4-11 | 17 | 7-27 | 0 | 0-0 | 0 | 0-1 |

|

|

||||||||

Based on Medicare claims data for 576,875 fee-for-service beneficiaries treated at least once by one of 2,284 Community Tracking Study primary care physicians in the year 2005. Peer network size was calculated separately as the sum of 1) the number of other practices where physicians also treated the primary patients of the CTS primary care physician; or 2) the practice of the physician that served as the primary provider for the CTS primary care physician's other (non-primary) Medicare patients. Primary patients were identified as beneficiaries for whom the CTS primary care physician billed the greatest number of evaluation and management visits in year 2005. Ties were resolved by assignment to the physician who billed for the greatest total charges for that beneficiary. Primary patients accounted for a median of 50% of a CTS primary care physician's Medicare panel.

Denotes inter-quartile range.

The number of chronic conditions was determined using the method of Hwang et al. These patients accounted for a median of 31 percent of each CTS primary care physician's Medicare panel.

Monthly medians were calculated based on visits in March, June, and September 2005. IQR denotes inter-quartile range.

Appendix B.2.

Number of Other Practices Among Whom Primary care physicians Have to Coordinate Care for Fee-for-Service Medicare Beneficiaries Who Are Their Primary- versus Non-primary Patients, by the Characteristics of the Physicians, Their Practices, and Their Patient Panels.

| Care of Primary Patients | Care of Non-primary Patients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician and Practice Characteristics | N (%) Total = 2,284 | Number of Peers per 100 Medicare Beneficiaries, Median (IQR) | Total Number of Peers, Median (IQR) | Number of Peers per 100 Medicare Beneficiaries, Median (IQR) | Total Number of Peers, Median (IQR) |

|

|

|||||

| Years in practice | |||||

| <5 | 366 (15.4) | 33 (15-33) | 54 (19-99) | 22 (15-36) | 35 (19-60) |

| 5-9 | 451 (18.3) | 34 (18-62) | 81 (22-152) | 20 (13-30) | 43 (20-68) |

| >9 | 1,467 (66.3) | 41 (23-73) | 104 (55-151) | 17 (12-25) | 37 (20-62) |

| Practice type | |||||

| Solo/2-person | 885 (39.6) | 54 (34-92) | 114 (67-170) | 19 (14-27) | 40 (19-67) |

| Small group, 3-10 | 325 (15.0) | 34 (20-57) | 116 (68-161) | 15 (11-22) | 43 (29-78) |

| Medium group, 11-50 | 164 (6.8) | 34 (21-56) | 115 (43-146) | 15 (10-22) | 44 (28-60) |

| Large group, >50 | 96 (4.8) | 37 (17-61) | 109 (38-158) | 13 (9-21) | 40 (21-72) |

| Medical school | 130 (4.5) | 37 (23-65) | 46 (22-85) | 23 (15-33) | 25 (15-44) |

| Hospital office/Other | 592 (25.2) | 22 (10-45) | 59 (15-105) | 20 (13-36) | 40 (21-63) |

| Group/staff health maintenance organization | 92 (4.1) | 30 (13-59) | 28 (4-52) | 18 (10-27) | 12 (2-27) |

| Percent of revenue derived from Medicaid | |||||

| 0-5% | 972 (38.9) | 52 (28-87) | 112 (55-172) | 18 (13-27) | 41 (18-68) |

| 6-15% | 618 (30.4) | 37 (21-60) | 99 (54-148) | 16 (10-24) | 38 (23-60) |

| >15% | 694 (30.8) | 29 (14-53) | 62 (16-107) | 20 (14-33) | 39 (18-63) |

| Urban | 1,985 (80.6) | 45 (23-75) | 90 (39-149) | 19 (13-29) | 37 (18-67) |

| Rural | 299 (19.4) | 28 (14-35) | 93 (42-139) | 13 (9-21) | 42 (28-59) |

| Census division | |||||

| New England | 190 (7.8) | 36 (18-64) | 68 (25-108) | 17 (14-24) | 34 (18-55) |

| Mid-Atlantic | 319 (12.0) | 64 (37-96) | 127 (58-180) | 22 (16-31) | 39 (19-72) |

| East North Central | 409 (17.9) | 39 (22-50) | 96 (60-140) | 16 (10-23) | 35 (20-54) |

| West North Central | 82 (3.0) | 33 (16-56) | 57 (19-94) | 16 (10-26) | 27 (16-41) |

| South Atlantic | 482 (20.9) | 37 (20-68) | 118 (57-156) | 17 (12-26) | 50 (29-83) |

| East South Central | 82 (5.8) | 28 (16-40) | 116 (80-159) | 13 (10-19) | 56 (33-74) |

| West South Central | 240 (10.4) | 36 (10-64) | 90 (23-159) | 20 (13-29) | 54 (26-71) |

| Mountain | 156 (6.6) | 34 (17-79) | 74 (40-161) | 19 (13-33) | 37 (14-88) |

| Pacific | 324 (15.6) | 39 (23-72) | 56 (22-102) | 20 (13-34) | 27 (11-44) |

| Number of specialist physicians per 1,000 capita | |||||

| Lowest quintile | 393 (20.2) | 31 (17-45) | 91 (39-134) | 15 (9-24) | 40 (24-56) |

| Fourth quintile | 423 (19.9) | 37 (18-70) | 78 (37-143) | 17 (13-26) | 39 (19-58) |

| Third quintile | 465 (19.8) | 50 (23-85) | 74 (30-139) | 20 (14-33) | 28 (12-58) |

| Second quintile | 428 (18.2) | 38 (23-64) | 107 (54-149) | 17 (12-26) | 44 (20-76) |

| Highest quintile | 575 (21.9) | 51 (22-77) | 108 (46-169) | 20 (14-30) | 44 (24-74) |

| Patient Panel Characteristics | |||||

| Number of Medicare beneficiaries | |||||

| 1-100 | 623 (24.4) | 73 (29-116) | 28 (8-62) | 28 (17-43) | 11 (4-17) |

| 101-200 | 523 (21.7) | 57 (31-81) | 81 (45-119) | 20 (15-28) | 29 (21-41) |

| 201-400 | 665 (29.3) | 39 (26-54) | 114 (68-149) | 17 (13-23) | 47 (35-65) |

| >400 | 473 (24.6) | 23 (15-39) | 149 (97-205) | 13 (9-20) | 81 (54-125) |

| Mean number of chronic conditions | |||||

| Lowest quartile | 576 (24.4) | 41 (27-66) | 72 (39-126) | 16 (11-24) | 27 (14-47) |

| Third quartile | 597 (25.6) | 37 (19-66) | 97 (50-146) | 16 (10-24) | 38 (22-55) |

| Second quartile | 500 (24.7) | 40 (18-71) | 118 (53-164) | 16 (13-25) | 46 (26-68) |

| Highest quartile | 611 (25.3) | 34 (15-72) | 82 (27-148) | 25 (18-39) | 54 (24-98) |

|

|

|||||

Based on Medicare claims data for 576,875 fee-for-service beneficiaries treated at least once by one of 2,284 Community Tracking Study primary care physicians in the year 2005. Peer network size was calculated as the sum of 1) the number of other practices where physicians also treated the primary patients of the CTS primary care physician; plus 2) the practice of the physician that served as the primary provider for the CTS primary care physician's other (non-primary) Medicare patients. Primary patients were identified as beneficiaries for whom the CTS primary care physician billed the greatest number of evaluation and management visits (Plurality assignment) or with the added criterion that the CTS primary care physician billed for at least 50% of evaluation and management visits (Majority assignment) in year 2005. Ties were resolved by assignment to the physician who billed for the greatest total charges for that beneficiary. Primary patients accounted for a median of 50% and 30% of a CTS primary care physician's Medicare panel under Plurality and Majority assignment, respectively. IQR denotes inter-quartile range. Counts of peers treating primary- versus non-primary patients were not de-duplicated here, and hence may sum to be greater than the corresponding counts of peers in Tables 1 and 2, which were de-duplicated to include only unique physicians or practices.

Footnotes

Reproducible Research Statements: Protocol: Available by contacting Dr. Pham

Statistical code: Not available

Data: Not available

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Primary Care: American's Health in a New Era. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Starfield B. Primary Care: Balancing Health Needs, Services, and Technology. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDonald KM, Sundaram V, Bravata DM, et al. Care Coordination. In: Shojania KG, McDonald KM, Wachter RM, Owens DK, editors. Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies Technical Review 9(Prepared by the Stanford University-UCSF Evidence-based Practice Center under contract 290-02-0017) Vol. 7. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Jun, 2007. AHRQ Publication No. 04(07)-0051-7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barr M, Ginsburg J. The Advanced Medical Home: A Patient-Centered, Physician-Guided Model of Health Care. American College of Physicians; Philadelphia, PA: [Accessed August 20, 2007]. http://www.acponline.org/hpp/adv_med.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century In America. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. p. 337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berenson RA, Horvath J. Confronting the barriers to chronic care management in Medicare. Health Affairs (Millwood) 2003 Jan-Jun; doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w3.37. Suppl Network Exclusives:W3-37-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.U.S. Congress. Tax Relief and Health Care Act of 2006. H.R.6408. Section 204 Medical Home Demonstration Project [Google Scholar]

- 8.UnitedHealth Group. UnitedHealth Group and physician groups to launch “Medical Home” pilot program to reward primary care doctors who improve patients' total health. UnitedHealth Group; Minneapolis, MN: [Accessed August 20, 2007]. At: http://www.unitedhealthgroup.com/news/rel2007/0806_medical_home_print.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: [Accessed April 16, 2008]. CAHPS Clinician and Group Survey. https://www.cahps.ahrq.gov/content/products/CG/PROD_CG_CG40Products.asp?p=1021&s=213. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pham HH, Schrag D, O'Malley AS, Wu B, Bach PB. Care patterns in Medicare and their implications for pay for performance. N Engl J Med. 2007 Mar 15;356(11):1130–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa063979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Center for Studying Health System Change. Washington, D.C: [Accessed August 8, 2007]. Physician Survey Methodology Report, 2000-2001. Technical Publication No 38; Available at: http://hschange.org/CONTENT/570/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bach PB, Pham HH, Schrag D, Tate RC, Hargraves JL. Primary care physicians Who Treat Blacks and Whites. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:575–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa040609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asch DA, Jedrziewski MK, Christakis NA. Response rates to mail surveys published in medical journals. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1997;50:1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiner JP, Parente ST, Garnick DW, et al. Variation in office-based quality: a claims-based profile of care provided to Medicare patients with diabetes. JAMA. 1995;273:1503–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.19.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hwang W, et al. Out-of-Pocket Medical Spending for Care of Chronic Conditions. Health Affairs. 2001;20(6):267–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elixhauser A, et al. Comorbidity Measures for Use with Administrative Data. Medical Care. 1998;36(1):8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S. Bureau of the Census. Census Regions and Divisions of the United States. U.S. Bureau of the Census; [Accessed September 7, 2007]. Washington, DC. At http://www.census.gov/geo/www/us_regdiv.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schrag D, Xu F, Hanger M, Elkin E, Bicknell NA, Bach PB. Fragmentation of care for frequently hospitalized urban residents. Medical Care. 2006 Jun;44(6):560–7. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000215811.68308.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Druss BG, Marcus SC, Olfson M, Tanielian T, Pincus HA. Trends in care by nonphysician clinicians in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003 Jan 9;348(2):130–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa020993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bynum JP, Bernal-Delgado E, Gottlieb D, Fisher E. Assigning ambulatory patients and their physicians to hospitals: a method for obtaining population-based provider measurements. Health Services Research. 2007 Feb;42(1 Pt 1):45–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartschat W, Burrington-Brown J, Carey S, et al. Surveying the RHIO landscape. A description of current RHIO models, with a focus on patient identification. J Amer Health Inform Manage Assoc. 2006 Jan;77(1):64A–64D. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grossman JM, Reed MC. Issue Brief No 106 Center for Studying Health System Change. Washington, D.C: 2006. Nov, Clinical information technology gaps persist among physicians. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwait J, Valente TW, Celentano DD. Interorganizational relationships among HIV/AIDS service organizations in Baltimore: a network analysis. J Urban Hlth. 2001 Sep;78(3):468–87. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]